Home | Category: Age of Caesar

CIVIL WAR AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON

Caesar and Pompey at the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena

After Julius Caesar finished subduing Gaul in 51 B.C., he defied the Republican tradition of victorious Roman generals not being allowed to return to Rome with their armies out of fear they would try to overthrow the government, which is exactly what Caesar did. By crossing the Rubicon Caesar declared war on the political establishment of his day. For many historians it marked the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire. To this day “crossing the Rubicon” describes a decision from which there is no return.

By crossing the Rubicon Caesar gambled that he could not only beat his military rival Pompey but also could also outmaneuver conservative politicians like Cicero and Cato. Some historians say Caesar’s move marked the end of period in which foreign adventures created larger armies and more powerful generals and it was only a matter of time until they threatened the political status quo.

Caesar marched into Rome with his army in and seized control of the government and the treasury and declared himself dictator while Pompey, in command of the Roman navy, fled to Greece. Five years of civil war followed. Caesar defeated Pompey in a series of land battles that took place throughout the Roman empire over a four years period. After Caesar led a successful campaign in Iberia (Spain), he defeated Pompey in Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt. The Ptolemies refused to provide quarter for a loser and had him executed and cut off his head. This made Caesar the unchallenged leader. Caesar said, “It is more important for the state that I should survive...I have long had my fill of power and glory; but should anything happen to me, Rome will enjoy no peace.”

Timeline of Events Around the Time Caesar Crossed the Rubicon

58-50 B.C.: As governor of the province, Caesar conducts a series of military campaigns to conquer Gaul, boosting his political career, bringing him the wealth and endearing him among the Roman masses.

50 B.C.: Following his victories in Gaul, Caesar attempts to return to Rome with his army, a breach of Roman law, and his former ally Pompey and his enemies in the Senate order him to either disband his army or stay of Italy proper.

January 10-11, 49 B.C.: Faced with an ultimatum from the Senate, Caesar and the 13th Legion cross the Rubicon, the official border between Gaul and Italy, a decision that leads to civil war.

49 B.C.: As Caesar advances on Rome, Pompey and his allies retreat south, ultimately fleeing Italy for Greece. Caesar defeats Pompey’s forces in Spain.

48 B.C.: Caesar pursues Pompey across the Adriatic and decisively defeats him at the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece. After the loss, Pompey flees to Egypt where he is assassinated.

46 B.C.: Caesar defeats Pompey’s remaining followers at Thapsus in North Africa. Caesar becomes dictator of Rome. [Source: Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History magazine, March-April 2017]

RELATED ARTICLES:

JULIUS CAESAR (102-44 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR’S LIFE AND CHARACTER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR'S RISE AS A POLITICIAN: CICERO, CATO AND THE CATILINE CONSPIRACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR'S MILITARY CAREER: SKILLS, LEADERSHIP, VICTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, POMPEY AND CRASSUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, THE CROSSING OF THE RUBICON AND THE SITUATION IN ROME AT THE TIME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR’S DICTATORSHIP factsanddetails.com ;

ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Caesar Versus Pompey: Determining Rome’s Greatest General, Statesman & Nation-Builder” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Civil War of Caesar” (Penguin Classics) by Julius Caesar and Jane P. Gardner Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Civil War: 49–44 BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2023) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Army: the Evolution, Composition, Tactics, Equipment & Battles of the Roman Army” by Harry Pratt Judson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2002) Amazon.com

“Pharsalus 48 BC: Caesar and Pompey – Clash of the Titans”, Illustrated, by Si Sheppard, Adam Hook, (2006) Amazon.com;

“Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny” by Edward Watts (2020), Illustrated Amazon.com;

“Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (2003) Amazon.com

“The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic” by Mike Duncan (2017) Amazon.com

“The First Triumvirate: The History of the Men Who Led Rome Near the End of the Republic” by Charles River Editors (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of the Roman Republic: Roman History, Books 36-40 (Oxford World's Classics)

by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

“Fall of the Roman Republic (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch Amazon.com;

“The Roman Republic of Letters: Scholarship, Philosophy, and Politics in the Age of Cicero and Caesar” by Katharina Volk (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Last Generation of the Roman Republic” by Erich S. Gruen (1974) Amazon.com

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics Hardcover) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works : Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War : in One Volume, with Maps, Annotations, Appendices, and Encyclopedic Index” by 2017) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Roman Republic 264–30 BC: History, Organization and Equipment

by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

Situation in Rome When Caesar Crossed the Rubicon

Caesar crossing the Rubicon

While Caesar was away in Gaul, Crassus was killed and Pompey became leader. Pompey wielded great power and declared Caesar a public enemy and ordered him to disband his army. Caesar refused. When he moved his army from Gaul into Rome’s formal territory, it was interpreted as a declaration of war against Rome. Caesar reached the border of greater Rome at the Rubicon River. He then he plunged his horse in the water, shouting , “The die is caste.”

While Julius Caesar was absent in Gaul, the ties which bound the three leaders of the Triumvirate — Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great), and Marcus Licinius Crassus — together were becoming weaker and weaker. The position of Crassus tended somewhat, as long as he was alive, to allay the growing suspicion between the two great rivals. But after Crassus departed for the East to take control of his province in Syria, he invaded Parthia, was badly defeated, lost the Roman standards, and was himself killed (53 B.C.). The death of Crassus practically dissolved the triumvirate; or we might rather say, it reduced the triumvirate to a duumvirate. But the relation between the two leaders was now no longer one of friendly support, but one of mutual distrust. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

The growing estrangement between Pompey and Caesar was increased when the senate appointed Pompey “sole consul” in 52 B.C. This was not intended as an affront to Caesar, but was evidently demanded to meet a real emergency. The city was distracted by continual street fights between the armed bands of Clodius, the demagogue, and those of T. Annius Milo, who professed to be defending the cause of the senate. In one of these broils Clodius was killed. His excited followers made his death the occasion of riotous proceedings. His body was burned in the Forum by the wild mob, and the senate house was destroyed by fire. In the anarchy which followed, the senate felt obliged to confer some extraordinary power upon Pompey. On the proposal of Cato, he was appointed “consul without a colleague." Under this unusual title Pompey restored order to the state, and was looked upon as “the savior of society." He became more and more closely bound to the cause of the senate; and the senate recognized its obligations to him by prolonging his command in Spain for five years. \~\

Caesar Advances Towards Rome

After Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his army he advanced towards Rome. Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “There were not about him at that time above three hundred horse and five thousand foot; for the rest of his army, which was left behind the Alps, was to be brought after him by officers who had received orders for that purpose. But he thought the first motion towards the design which he had on foot did not require large forces at present, and that what was wanted was to make this first step suddenly, and so to astound his enemies with the boldness of it; as it would be easier, he thought, to throw them into consternation by doing what they never anticipated than fairly to conquer them, if he had alarmed them by his preparations. And therefore he commanded his captains and other officers to go only with their swords in their hands, without any other arms, and make themselves masters of Ariminum, a large city of Gaul, with as little disturbance and bloodshed as possible. He committed the care of these forces to Hortensius, and himself spent the day in public as a stander-by and spectator of the gladiators, who exercised before him. A little before night he attended to his person, and then went into the hall, and conversed for some time with those be had invited to supper, till it began to grow dusk, when he rose from table and made his excuses to the company, begging them to stay till he came back, having already given private directions to a few immediate friends that they should follow him, not all the same way, but some one way, some another. He himself got into one of the hired carriages, and drove at first another way, but presently turned towards Ariminum. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“When he came to the river Rubicon, which parts Gaul within the Alps from the rest of Italy, his thoughts began to work, now he was just entering upon the danger, and he wavered much in his mind when he considered the greatness of the enterprise into which he was throwing himself. He checked his course and ordered a halt, while he revolved with himself, and often changed his opinion one way and the other, without speaking a word. This was when his purposes fluctuated most; presently he also discussed the matter with his friends who were about him (of which number Asinius Pollio was one), computing how many calamities his passing that river would bring upon mankind, and what a relation of it would be transmitted to posterity. At last, in a sort of passion, casting aside calculation, and abandoning himself to what might come, and using the proverb frequently in their mouths who enter upon dangerous and bold attempts, "The die is cast," with these words he took the river.

Roman Republic in 51 BC with Caesars conquests in Gaul and Europe and Pompey's conquests in Asia and North Africa

Once over, he used all expedition possible, and before it was day reached Ariminum and took it. It is said that the night before he passed the river he had an impious dream, that he was unnaturally familiar with his own mother. As soon as Ariminum was taken, wide gates, so to say, were thrown open, to let in war upon every land alike and sea, and with the limits of the province, the boundaries of the laws were transgressed. Nor would one have thought that, as at other times, the mere men and women fled from one town of Italy to another in their consternation, but that the very towns themselves left their sites and fled for succour to each other. The city of Rome was overrun, as it were, with a deluge, by the conflux of people flying in from all the neighbouring places. Magistrates could not longer govern, nor the eloquence of any orator quiet it; it was all but suffering shipwreck by the violence of its own tempestuous agitation. The most vehement contrary passions and impulses were at work everywhere. Nor did those who rejoiced at the prospect of the change altogether conceal their feelings, but when they met, as in so great a city they frequently must, with the alarmed and dejected of the other party, they provoked quarrels by their bold expressions of confidence in the event. Pompey, sufficiently disturbed of himself, was yet more perplexed by the clamours of others; some telling him that he justly suffered for having armed Caesar against himself and the government; others blaming him for permitting Caesar to be insolently used by Lentulus, when he made such ample concessions, and offered such reasonable proposals towards an accommodation. Favonius bade him now stamp upon the ground; for once talking big in the senate, he desired them not to trouble themselves about making any preparations for the war, for that he himself, with one stamp of his foot, would fill all Italy with soldiers. Yet still Pompey at that time had more forces than Caesar; but he was not permitted to pursue his own thoughts, but, being continually disturbed with false reports and alarms, as if the enemy was close upon him and carrying all before him, he gave way and let himself be borne down by the general cry. He put forth an edict declaring the city to be in a state of anarchy, and left it with orders that the senate should follow him, and that no one should stay behind who did not prefer tyranny to their country and liberty.

“The consuls at once fled, without making even the usual sacrifices; so did most of the senators, carrying off their own goods in as much haste as if they had been robbing their neighbours. Some, who had formerly much favoured Caesar's cause, in the prevailing alarm quitted their own sentiments, and without any prospect of good to themselves were carried along by the common stream. It was a melancholy thing to see the city tossed in these tumults, like a ship given up by her pilots, and left to run, as chance guides her, upon any rock in her way. Yet, in spite of their sad condition people still esteemed the place of their exile to be their country for Pompey's sake, and fled from Rome, as if it had been Caesar's camp. Labienus even, who had been one of Caesar's nearest friends, and his lieutenant, and who had fought by him zealously in the Gallic wars, now deserted him, and went over to Pompey. Caesar sent all his money and equipage after him, and then sat down before Corfinium, which was garrisoned with thirty cohorts under the command of Domitius. He, in despair of maintaining the defence, requested a physician, whom he had among his attendants, to give him poison; and taking the dose, drank it, in hopes of being despatched by it. But soon after, when he was told that Caesar showed the utmost clemency towards those he took prisoners, he lamented his misfortune, and blamed the hastiness of his resolution. His physician consoled him by informing him that he had taken a sleeping draught, not a poison; upon which, much rejoiced, and rising from his bed, he went presently to Caesar and gave him the pledge of his hand, yet afterwards again went over to Pompey. The report of these actions at Rome quieted those who were there, and some who had fled thence returned.

Civil War After Caesar Crosses the Rubicon

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History magazine: “The choice facing Rome was either decades of more factionalism and political chaos, or accepting a strongman to impose reform, and set its affairs in order. On swiftly passing to the far bank of this minor river, Caesar set the republic hurtling down the second course.” [Source: Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History magazine, March-April 2017]

Caesar marched into Rome with his army and seized control of the government and the treasury and declared himself dictator while Pompey, in command of the Roman navy, fled to Greece. But this campaign was just the beginning. Five years of civil war followed. Caesar was forced to cover huge distances in his effort to destroy Pompey and his extensive allies across the Roman world.

Caesar's army at the Rubicon

Caesar defeated Pompey in a series of land battles that took place throughout the Roman empire over a four years period. After Caesar put down a revolt in modern-day Marseille in France and routed Pompey’s loyalists in Spain at the Battle of Ilerda in June 49 B.C., he defeated Pompey in Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt. The Ptolemies refused to provide quarter for a loser and had him executed and cut off his head.

Suetonius wrote: “In all the civil wars he suffered not a single disaster except through his lieutenants, of whom Gaius Curio perished in Africa, Gaius Antonius fell into the hands of the enemy in Illyricum, Publius Dolabella lost a fleet also off Illyricum, and Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus an army in Pontus. Personally he always fought with the utmost success, and the issue was never even in doubt save twice: once at Dyrrachium, where he was put to flight, and said of Pompeius, who failed to follow up his success, that he did not know how to use a victory; again in Spain, in the final struggle, when, believing the battle lost, he actually thought of suicide.” [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

The defeat of Pompey and his allies made Caesar the unchallenged leader. Caesar said, “It is more important for the state that I should survive...I have long had my fill of power and glory; but should anything happen to me, Rome will enjoy no peace."

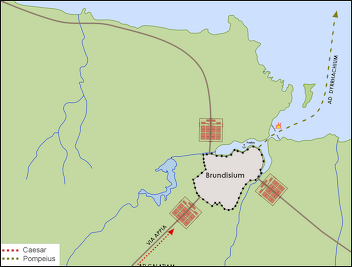

Caesar’s Early Civil War Campaign in Italy

In 49 B.C., Caesar advanced on Rome while Pompey and his allies retreated southward, ultimately fleeing Italy for Greece. Caesar knew the value of time; at the instant when he decided upon war, he invaded Italy with a single legion. Pompey, unprepared for such a sudden move and not relying upon the two legions which the senate had taken from Caesar, was obliged to withdraw to Brundisium (Brindisi in southeast Italy). Besieged in this place by Caesar, he skillfully withdrew his forces to Greece, and left Caesar master of Italy. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Suetonius wrote: “The sum total of his movements after that is, in their order, as follows: He overran Umbria, Picenum, and Etruria, took prisoner Lucius Domitius, who had been irregularly named his successor, and was holding Corfinium with a garrison, let him go free, and then proceeded along the Adriatic to Brundisium, where Pompeius and the consuls had taken refuge, intending to cross the sea as soon as might be. After vainly trying by every kind of hindrance to prevent their sailing, he marched off to Rome, and after calling the senate together to discuss public business, went to attack Pompeius' strongest forces, which were in Hispania under command of three of his lieutenants — Marcus Petreius, Lucius Afranius, and Marcus Varro — saying to his friends before he left "I go to meet an army without a leader, and I shall return to meet a leader without an army." And in fact, though his advance was delayed by the siege of Massilia, which had shut its gates against him, and by extreme scarcity of supplies, he nevertheless quickly gained a complete victory. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

Caesar's Campaign against Pompey's forces in Italy and Greece and his campaign in Asia

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Caesar took into his army Domitius's soldiers, as he did all those whom he found in any town enlisted for Pompey's service. Being now strong and formidable enough, he advanced against Pompey himself, who did not stay to receive him, but fled to Brundusium, having sent the consuls before with a body of troops to Dyrrhachium. Soon after, upon Caesar's approach, he set to sea, as shall be more particularly related in his Life. Caesar would have immediately pursued him, but wanted shipping, and therefore went back to Rome, having made himself master of all Italy without bloodshed in the space of sixty days. When he came thither, he found the city more quiet than he expected, and many senators present, to whom he addressed himself with courtesy and deference, desiring them to send to Pompey about any reasonable accommodation towards a peace. But nobody complied with this proposal; whether out of fear of Pompey, whom they had deserted, or that they thought Caesar did not mean what he said, but thought it his interest to talk plausibly. Afterwards, when Metellus, the tribune, would have hindered him from taking money out of the public treasure, and adduced some laws against it, Caesar replied that arms and laws had each their own time; "If what I do displeases you, leave the place; war allows no free talking. When I have laid down my arms, and made peace, come back and make what speeches you please. And this," he added, "I tell you in diminution of my own just right, as indeed you and all others who have appeared against me and are now in my power may be treated as I please." Having said this to Metellus, he went to the doors of the treasury, and the keys being not to be found, sent for smiths to force them open. Metellus again making resistance and some encouraging him in it, Caesar, in a louder tone, told him he would put him to death if he gave him any further disturbance. "And this," said he, "you know, young man, is more disagreeable for me to say than to do." These words made Metellus withdraw for fear, and obtained speedy execution henceforth for all orders that Caesar gave for procuring necessaries for the war. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

Caesar’s Campaign in Spain

Caesar was now between two hostile forces, the army in Spain under Pompey’s lieutenants, and the army in Greece under Pompey himself. He must now defeat these armies separately before they could be united against him. As he had no fleet with which to follow Pompey into Greece, he decided at once to attack the army in Spain. He dispatched his Gallic legions across the Pyrenees, while he secured himself at Rome. He entered the city, and dispelled the fear that there might be repeated the horrors of the first civil war. He showed that he was neither a Marius nor a Sulla. Rejoining his legions in Spain, he soon defeated Pompey’s lieutenants. When he returned to Rome he found that he had been proclaimed dictator. He resigned this title and accepted the office of consul. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “He was now proceeding to Spain, with the determination of first crushing Afranius and Varro, Pompey's lieutenants, and making himself master of the armies and provinces under them, that he might then more securely advance against Pompey, when he had no enemy left behind him. In this expedition his person was often in danger from ambuscades, and his army by want of provisions, yet he did not desist from pursuing the enemy, provoking them to fight, and hemming them with his fortifications, till by main force he made himself master of their camps and their forces. Only the generals got off, and fled to Pompey.” [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“When Caesar came back to Rome,Piso, his father-in-law, advised him to send men to Pompey to treat of a peace; but Isauricus, to ingratiate himself with Caesar, spoke against it. After this, being created dictator by the senate, he called home the exiles, and gave back their rights as citizens to the children of those who had suffered under Sylla; he relieved the debtors by an act remitting some part of the interest on their debts, and passed some other measures of the same sort, but not many. For within eleven days he resigned his dictatorship, and having declared himself consul, with Servilius Isauricus, hastened again to the war. He marched so fast that he left all his army behind him, except six hundred chosen horse and five legions, with which he put to sea in the very middle of winter, about the beginning of the month of January (which corresponds pretty nearly with the Athenian month Posideon), and having passed the Ionian Sea, took Oricum and Apollonia, and then sent back the ships to Brundusium, to bring over the soldiers who were left behind in the march. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“They, while yet on the march, their bodies now no longer in the full vigour, and they themselves weary with such a multitude of wars, could not but exclaim against Caesar, "When at last, and where, will this Caesar let us be quiet? He carries us from place to place, and uses us as if we were not to be worn out, and had no sense of labour. Even our iron itself is spent by blows, and we ought to have some pity on our bucklers, and breastplates, which have been used so long. Our wounds, if nothing else, should make him see that we are mortal men whom he commands, subject to the same pains and sufferings as other human beings. The very gods themselves cannot force the winter season, or hinder the storms in their time; yet he pushes forward, as if he were not pursuing, but flying from an enemy." So they talked as they marched leisurely towards Brundusium. But when they came thither, and found Caesar gone off before them, their feelings changed, and they blamed themselves as traitors to their general. They now railed at their officers for marching so slowly, and placing themselves on the heights overlooking the sea towards Epirus, they kept watch to see if they could espy the vessels which were to transport them to Caesar.”

Caesar Prepares to Fight Pompey in Greece

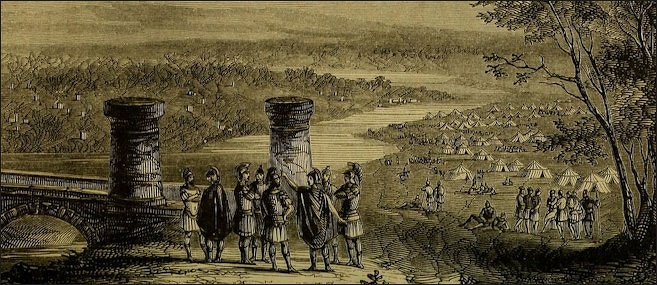

Caesar arrives in Brundisium while Pompey flees

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: Caesar in the meantime was posted in Apollonia, but had not an army with him able to fight the enemy, the forces from Brundusium being so long in coming, which put him to great suspense and embarrassment what to do. At last he resolved upon a most hazardous experiment, and embarked, without any one's knowledge, in a boat of twelve oars, to cross over to Brundusium, though the sea was at that time covered with a vast fleet of the enemies. He got on board in the night-time, in the dress of a slave, and throwing himself down like a person of no consequence lay along at the bottom of the vessel. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“The river Anius was to carry them down to sea, and there used to blow a gentle gale every morning from the land, which made it calm at the mouth of the river, by driving the waves forward; but this night there had blown a strong wind from the sea, which overpowered that from the land, so that where the river met the influx of the seawater and the opposition of the waves it was extremely rough and angry; and the current was beaten back with such a violent swell that the master of the boat could not make good his passage, but ordered his sailors to tack about and return. Caesar, upon this, discovers himself, and taking the man by the hand, who was surprised to see him there, said, "Go on, my friend, and fear nothing; you carry Caesar and his fortune in your boat." The mariners, when they heard that, forgot thestorm, and laying all their strength to their oars, did what they could to force their way down the river. But when it was to no purpose, and the vessel now took in much water, Cæsar finding himself in such danger in the very mouth of the river, much against his will permitted the master to turn back. When he was come to land, his soldiers ran to him in a multitude, reproaching him for what he had done, and indignant that he should think himself not strong enough to get a victory by their sole assistance, but must disturb himself, and expose his life for those who were absent, as if he could not trust those who were with him.

“After this, Antony came over with the forces from Brundisium, which encouraged Cæsar to give Pompey battle, though he was encamped very advantageously, and furnished with plenty of provisions both by sea and land, whilst he himself was at the beginning but ill-supplied, and before the end was extremely pinched for want of necessaries, so that his soldiers were forced to dig up a kind of root which grew there, and tempering it with milk, to feed on it. Sometimes they made a kind of bread of it, and advancing up to the enemy’s outposts, would throw in these loaves, telling them, that as long as the earth produced such roots they would not give up blockading Pompey. But Pompey took what care he could, that neither the loaves nor the words should reach his men, who were out of heart and despondent, through terror at the fierceness and hardiness of their enemies, whom they looked upon as a sort of wild beasts. There were continual skirmishes about Pompey’s outworks, in all which Cæsar had the better, except one, when his men were forced to fly in such a manner that he had like to have lost his camp. For Pompey made such a vigorous sally on them that not a man stood his ground; the trenches were filled with the slaughter, many fell upon their own ramparts and bulwarks, whither they were driven in flight by the enemy.

“Cæsar met them, and would have turned them back, but could not. When he went to lay hold of the ensigns, those who carried them threw them down, so that the enemies took thirty-two of them. He himself narrowly escaped; for taking hold of one of his soldiers, a big and strong man, that was flying by him, he bade him stand and face about; but the fellow, full of apprehensions from the danger he was in, laid hold of his sword, as if he would strike Cæsar, but Cæsar’s armor-bearer cut off his arm. Cæsar’s affairs were so desperate at that time, that when Pompey, either through over-cautiousness, or his ill fortune, did not give the finishing stroke to that great success, but retreated after he had driven the routed enemy within their camp, Cæsar, upon seeing his withdrawal, said to his friends, “The victory to-day had been on the enemies’ side, if they had had a general who knew how to gain it.” When he was retired into his tent, he laid himself down to sleep, but spent that night as miserably as ever he did any, in perplexity and consideration with himself, coming to the conclusion that he had conducted the war amiss. For when he had a fertile country before him, and all the wealthy cities of Macedonia and Thessalv. he had neglected to carry the war thither, and had sat down by the seaside, where his enemies had such a powerful fleet, so that he was in fact rather besieged by the want of necessaries, than besieging others with his arms. Being thus distracted in his thoughts with the view of the difficulty and distress he was in, he raised his camp, with the intention of advancing towards Scipio, who lay in Macedonia; hoping either to entice Pompey into a country where he should fight without the advantage he now had of supplies from the sea, or to overpower Scipio, if not assisted.

“This set all Pompey’s army and officers on fire to hasten and pursue Cæsar, whom they concluded to be beaten and flying. But Pompey was afraid to hazard a battle on which so much depended, and being himself provided with all necessaries for any length of time, thought to tire out and waste the vigor of Cæsar’s army, which could not last long. For the best part of his men, though they had great experience, and showed an irresistible courage in all engagements, yet by their frequent marches, changing their camps,* attacking fortifications, and keeping long night-watches, were getting worn-out and broken; they being now old, their bodies less fit for labor, and their courage, also, beginning to give way with the failure of their strength. Besides, it was said that an infectious disease, occasioned by their irregular diet, was prevailing in Cæsar’s army, and what was of greatest moment, he was neither furnished with money nor provisions, so that in a little time he must needs fall of himself.

Caesar's and Pompey's movements across northern Greece

“For these reasons Pompey had no mind to fight him, but was thanked for it by none but Cato, who rejoiced at the prospect of sparing his fellow-citizens. For he when he saw the dead bodies of those who had fallen in the last battle on Cæsar’s side, to the number of a thousand, turned away, covered his face, and shed tears. But every one else upbraided Pompey for being reluctant to fight, and tried to goad him on by such nicknames as Agamemnon, and king of kings, as if he were in no hurry to lay down his sovereign authority, but was pleased to see so many commanders attending on him, and paying their attendance at his tent. Favonius, who affected Cato’s free way of speaking his mind, complained bitterly that they should eat no figs even this year at Tusculum, because of Pompey’s love of command. Afranius, who was lately returned out of Spain, and on account of his ill success there, labored under the suspicion of having been bribed to betray the army, asked why they did not fight this purchaser of provinces. Pompey was driven, against his own will, by this kind of language, into offering battle, and proceeded to follow Cæsar. Cæsar had found great difficulties in his march, for no country would supply him with provisions, his reputation being very much fallen since his late defeat. But after he took Gomphi, a town of Thessaly, he not only found provisions for his army, but physic too. For there they met with plenty of wine, which they took very freely, and heated with this, sporting and revelling on their march in bacchanalian fashion, they shook off the disease, and their whole constitution was relieved and changed into another habit.”

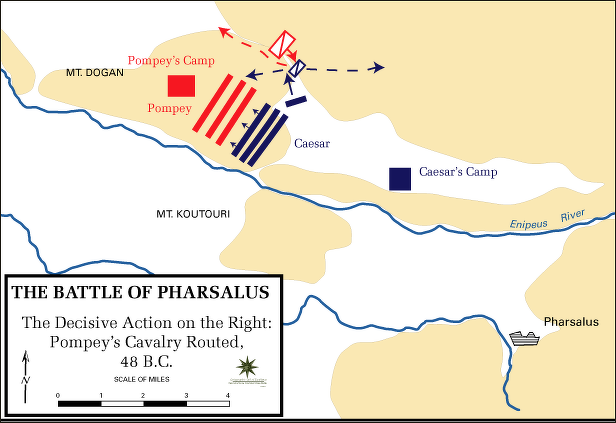

Caesar Defeats Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece

In 48 B.C., Caesar pursued Pompey across the Adriatic and decisively defeats him at the Battle of Pharsalus in in southern Thessaly, in Greece. Although Pompey's army outnumbered Caesar's — when commanded about 20,000 men compared to 40,000 for Pompey — Caesar's army was more experienced. The senate pressured Pompey to attack first, Pompey reluctantly did so. After the loss, Pompey fled to Egypt where he was assassinated.

In the beginning of 48 B.C., with the few ships that he had collected, he transported his troops from Brundisium across the Adriatic to meet the army of Pompey. In the first conflict, at Dyrrachium, he was defeated. He then retreated across the peninsula in the direction of Pharsalus in order to draw Pompey away from his supplies on the seacoast. Suetonius wrote: Caesar blockaded Pompey for almost four months behind mighty ramparts, finally routed him”[Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Plutarch wrote: “When the two armies were come into Pharsalia (Pharsalus), and both encamped there, Pompey’s thoughts ran the same way as they had done before, against fighting, and the more because of some unlucky presages, and a vision he had in a dream.† But those who were about him were so confident of success, that Domitius, and Spinther, and Scipio, as if they had already conquered, quarrelled which should succeed Cæsar in the pontificate. And many sent to Rome to take houses fit to accommodate consuls and prætors, as being sure of entering upon those offices, as soon as the battle was over. The cavalry especially were obstinate for fighting, being splendidly armed and bravely mounted, and valuing themselves upon the fine horses they kept, and upon their own handsome persons; as also upon the advantage of their numbers, for they were five thousand against one thousand of Cæsar’s. Nor were the numbers of the infantry less disproportionate, there being forty-five thousand of Pompey’s, against twenty-two thousand of the enemy. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Cæsar, collecting his soldiers together, told them that Corfinius* was coming up to them with two legions, and that fifteen cohorts more under Calenus were posted at Megara and Athens; he then asked them whether they would stay till these joined them, or would hazard the battle by themselves. They all cried out to him not to wait, but on the contrary to do whatever he could to bring about an engagement as soon as possible. When he sacrificed to the gods for the lustration of his army, upon the death of the first victim, the augur told him, within three days he should come to a decisive action. Cæsar asked him whether he saw any thing in the entrails, which promised an happy event. “That,” said the priest, “you can best answer yourself; for the gods signify a great alteration from the present posture of affairs. If, therefore, you think yourself well off now, expect worse fortune; if unhappy, hope for better.” The night before the battle, as he walked the rounds about midnight, there was a light seen in the heaven, very bright and flaming, which seemed to pass over Cæsar’s camp, and fall into Pompey’s. And when Cæsar’s soldiers came to relieve the watch in the morning, they perceived a panic disorder among the enemies. However, he did not expect to fight that day, but set about raising his camp with the intention of marching towards Scotussa.

“But when the tents were now taken down, his scouts rode up to him, and told him the enemy would give him battle. With this news he was extremely pleased, and having performed his devotions to the gods, set his army in battle array, dividing them into three bodies. Over the middlemost he placed Domitius Calvinus; Antony commanded the left wing, and he himself the right, being resolved to fight at the head of the tenth legion. But when he saw the enemies’ cavalry taking position against him, being struck with their fine appearance and their number, he gave private orders that six cohorts from the rear of the army should come round and join him, whom he posted behind the right wing, and instructed them what they should do, when the enemy’s horse came to charge. On the other side, Pompey commanded the right wing, Domitius the left, and Scipio, Pompey’s father-in-law, the centre. The whole weight of the cavalry was collected on the left wing, with the intent that they should outflank the right wing of the enemy, and rout that part where the general himself commanded. For they thought no phalanx of infantry could be solid enough to sustain such a shock, but that they must necessarily be broken and shattered all to pieces upon the onset of so immense a force of cavalry. When they were ready on both sides to give the signal for battle, Pompey commanded his foot who were in the front, to stand their ground, and without breaking their order, receive quietly the enemy’s first attack, till they came within javelin’s cast. Cæsar, in this respect, also, blames Pompey’s generalship, as if he had not been aware how the first encounter, when made with an impetus and upon the run, gives weight and force to the strokes, and fires the men’s spirits into a flame, which the general concurrence fans to full heat. He himself was just putting the troops into motion and advancing to the action, when he found one of his captains, a trusty and experienced soldier, encouraging his men to exert their utmost. Cæsar called him by his name, and said, “What hopes, Caius Crassinius, and what grounds for encouragement?” Crassinius stretched out his hand, and cried in a loud voice, “We shall conquer nobly, Cæsar; and I this day will deserve your praises, either alive or dead.” So he said, and was the first man to run in upon the enemy, followed by the hundred and twenty soldiers about him, and breaking through the first rank, still pressed on forwards with much slaughter of the enemy, till at last he was struck back by the wound of a sword, which went in at his mouth with such force that it came out at his neck behind.

“Whilst the foot was thus sharply engaged in the main battle, on the flank Pompey’s horse rode up confidently, and opened their ranks very wide, that they might surround the right wing of Cæsar. But before they engaged, Cæsar’s cohorts rushed out and attacked them, and did not dart their javelins at a distance, nor strike at the thighs and legs, as they usually did in close battle, but aimed at their faces. For thus Cæsar had instructed them, in hopes that young gentlemen, who had not known much of battles and wounds, but came wearing their hair long, in the flower of their age and height of their beauty, would be more apprehensive of such blows, and not care for hazarding both a danger at present and a blemish for the future. And so it proved, for they were so far from bearing the stroke of the javelins, that they could not stand the sight of them, but turned about, and covered their faces to secure them. Once in disorder, presently they turned about to fly; and so most shamefully ruined all.

Pompey's death

"For those who had beat them back, at once outflanked the infantry, and falling on their rear, cut them to pieces. Pompey, who commanded the other wing of the army, when he saw his cavalry thus broken and flying, was no longer himself, nor did he now remember that he was Pompey the Great, but like one whom some god had deprived of his senses, retired to his tent without speaking a word, and there sat to expect the event, till the whole army was routed, and the enemy appeared upon the works which were thrown up before the camp, where they closely engaged with his men, who were posted there to defend it. Then first he seemed to have recovered his senses, and uttering, it is said, only these words, “What, into the camp too?” he laid aside his general’s habit, and putting on such clothes as might best favor his flight, stole off. What fortune he met with afterwards, how he took shelter in Egypt, and was murdered there, we tell you in his Life.

“Cæsar, when he came to view Pompey’s camp, and saw some of his opponents dead upon the ground, others dying, said, with a groan, “This they would have; they brought me to this necessity. I, Caius Cæsar, after succeeding in so many wars, had been condemned, had I dismissed my army.”* These words, Pollio says, Cæsar spoke in Latin at that time, and that he himself wrote them in Greek; adding, that those who were killed at the taking of the camp, were most of them servants; and that not above six thousand soldiers fell. Cæsar incorporated most of the foot whom he took prisoners, with his own legions, and gave a free pardon to many of the distinguished persons, and amongst the rest, to Brutus, who afterwards killed him. He did not immediately appear after the battle was over, which put Cæsar, it is said, into great anxiety for him; nor was his pleasure less when he saw him present himself alive.

“There were many prodigies that foreshowed this victory, but the most remarkable that we are told of, was that at Tralles. In the temple of Victory stood Cæsar’s statue. The ground on which it stood was naturally hard and solid, and the stone with which it was paved still harder; yet it is said that a palm-tree shot itself up near the pedestal of this statue. In the city of Padua, one Caius Cornelius, who had the character of a good augur, the fellow-citizen and acquaintance of Livy, the historian, happened to be making some augural observations that very day when the battle was fought. And first, as Livy tells us, he pointed out the time of the fight, and said to those who were by him, that just then the battle was begun, and the men engaged. When he looked a second time, and observed the omens, he leaped up as if he had been inspired, and cried out, “Cæsar, you are victorious.” This much surprised the standers by, but he took the garland which he had on from his head, and swore he would never wear it again till the event should give authority to his art. This Livy positively states for a truth.”

Pompey Flees to Egypt and Caesar Takes Up with Cleopatra

Caesar's remorse over Pompey's death

Pompey fled to Egypt, where he tried to ally with the Ptolemy, the leader of Egypt. Ptolemy, however, knew Caesar was coming into Egypt for Pompey. Ptolemy had Pompey discreetly killed. Caesar was not happy about his son-in-law/rival being murdered by someone other than himself. In any case. Caesar had now accomplished the first part of his work, by taking possession of Italy and defeating the two armies of Pompey in Spain and Greece. He had established his title to supremacy. Especial honors were paid to him at Rome. He was made consul for five years, tribune for life, and dictator for one year. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Suetonius wrote: “ followed him in his flight to Alexandria, and when he learned that his rival had been slain, made war on King Ptolemy, whom he perceived to be plotting against his own safety as well; a war in truth of great difficulty, convenient neither in time nor place, but carried on during the winter season, within the walls of a well-provisioned and crafty foeman, while Caesar himself was without supplies of any kind and ill-prepared. Victor in spite of all, he turned over the rule of Egypt to Cleopatra and her younger brother [47 B.C.], fearing that if he made a province of it, it might one day under a headstrong governor be a source of revolution. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

Caesar now entered upon the second part of his work—that of pacifying the provinces. While in Egypt, be became fascinated by the charms of Cleopatra, and settled a dispute in which she was involved. That country was disturbed by a civil war between this princess and her brother Ptolemy. Each claimed the right to the throne. Caesar defeated the forces of Ptolemy and assigned the throne to Cleopatra, under the protection of two Roman legions. \~\

Caesar Helps Cleopatra Seize the Egyptian Throne

Caesar Julius Caesar arrived in Alexandria days after Pompey's murder. He barricaded himself in the Ptolemies' palace, the home from which Cleopatra had been exiled. From the desert she engineered a clandestine return, skirting enemy lines and Roman barricades, arriving after dark inside a sturdy sack. Over the succeeding months she stood at Caesar's side — pregnant with his child — while he battled her brother's troops. With their defeat, Caesar restored her to the throne.

Judith Thurman wrote in The New Yorker the morning after Cleopatra finagled her way into Caesar's stronghold “her brother dashed into the streets and nearly persuaded a mob to rise against the usurpers.Caesar's Praetorians dragged him back inside, but his handlers rallied their forces...In the ensuing wars against Caesar and Cleopatra, which the world's greatest general nearly lost (until reinforcements arrived, he was severely shorthanded), Ptolemy drowned. The victors celebrated with a leisurely Nile cruise, a visit to the pyramids, and some whistlestopping in the heartland. The public honeymoon demonstrated an inspired gift for mixing business with pleasures, and both with stagecraft." [Source: Judith Thurman, The New Yorker November 15, 2010]

Giving birth to Caesar's son, Thurman wrote, “consolidated her bands with his father, and with her own people and their priests, who rejoiced at a male heir. With a son as her symbolic co-regent and caesar as her protector, Cleopatra had no need to remarry. She henceforth governed alone — uniquely so among female monarchs of her period. Her autonomy depended on the fickle good will of Rome, and her exchange of favors with two Roman leaders.

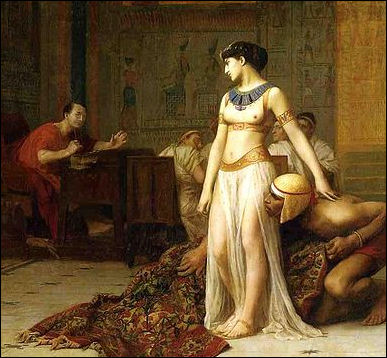

Cleopatra and Julius Caesar

Cleopatra emerges from a carpet

standing before Caesar Julius Caesar, who essentially the dictator of Rome in Cleopatra's time, arrived in Egypt during the civil war between Cleopatra and her brother. Caesar came to claim the debts Egypt owed Rome and Cleopatra saw in him a chance to win back her kingdom and expand it into Syria, Palestine and Asia Minor. Her alliance with Caesar seems to have been strategic, romantic and sexual. For his part Caesar made little mention of Cleopatra in his account of the Alexandrine wars.

Caesar initially didn't want to have anything to do with Cleopatra but he was delayed in his return to Rome by unfavorable winds. According to Plutarch's version of events she had herself rolled up in bedsheets and delivered to Caesar, who was so besotted with her he orchestrated a reconciliation between Cleopatra and her brother and then had Ptolemy kill his former partner Pothinus. Pliny is said to be the source the rolled-up-in-bedsheets story. Many doubt its veracity. In the 1963 film Cleopatra Elizabeth Taylor's Cleopatra spills out of Persian carpet at the feet of Caesar ready to crawl up his legs.

When Cleopatra met up with Caesar he was a balding epileptic with a lot of experience with women. He was 32 years older than her and married. The two of them sailed down the Nile together in a 300-foot barge with gardens and banquet rooms. In 47 B.C., Cleopatra gave birth to Caesar's son, Ptolemy Caesarian (“Little Caesar”) . To honor the event she had a coin minted showing her as Aphrodite nursing Eros.

Roman support of Cleopatra's armies won her full control of Egypt. She married her other little brother Ptolemy XIII and then poisoned him after Little Caesar was born. Her teenage sister, Arisnoe, who had tried to dethrone, was paraded in Rome in golden shackles but at leaste she was allowed to live in exile (at least until later one when Cleopatra persuaded Antony to have her dragged from her temple and put to death). and With things under control at home, Cleopatra went to Rome with Caesar. In Rome, she lived in one of Caesar's suburban palaces and impressed some with her wit and turned off others with her arrogance. Her presence in Rome caused quite stir and triggered a fad for anything associated with Egypt. Many women adopted Cleopatra's “melon” hairstyle (rows of tight briads gathered in a low bun).

Caesar and Cleopatra hosted great parties. The Roman leader even raised a golden statue to her in the temple of Venus. Even so Cleopatra was not well liked by powerful people like Cicero and her claim to any power was tied to Caesar. In 44 B.C., as Caesar was making plans to marry Cleopatra and legitimize their child, he was assassinated. This was a clear setback for Cleopatra's larger ambitions. Caesar's great-nephew Octavian was named his heir not Ptolemy Caesarian.

Cleopatra and Caesar’s War

Caesar giving Cleopatra

the Throne of Egypt Plutarch wrote in “Lives”:“As to the war in Egypt, some say it was at once dangerous and dishonorable, and noways necessary, but occasioned only by his passion for Cleopatra. Others blame the ministers of the king, and especially the eunuch Pothinus, who was the chief favorite, and had lately killed Pompey, who had banished Cleopatra, and was now secretly plotting Cæsar’s destruction, (to prevent which, Cæsar from that time began to sit up whole nights, under pretence of drinking, for the security of his person,) while openly he was intolerable in his affronts to Cæsar, both by his words and actions. For when Cæsar’s soldiers had musty and unwholesome corn measured out to them, Pothinus told them they must be content with it, since they were fed at another’s cost. He ordered that his table should be served with wooden and earthen dishes, and said Cæsar had carried off all the gold and silver plate, under pretence of arrears of debt. For the present king’s father owed Cæsar one thousand seven hundred and fifty myriads of money; Cæsar had formerly remitted to his children the rest, but thought fit to demand the thousand myriads at that time, to maintain his army. Pothinus told him that he had better go now and attend to his other affairs of greater consequence, and that he should receive his money at another time with thanks. Cæsar replied that he did not want Egyptians to be his counsellors, and soon after privately sent for Cleopatra from her retirement. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“She took a small boat, and one only of her confidents, Apollodorus, the Sicilian, along with her, and in the dusk of the evening landed near the palace. She was at a loss how to get in undiscovered, till she thought of putting herself into the coverlet of a bed and lying at length, whilst Apollodorus tied up the bedding and carried it on his back through the gates to Cæsar’s apartment. Cæsar was first captivated by this proof of Cleopatra’s bold wit, and was afterwards so overcome by the charm of her society, that he made a reconciliation between her and her brother, on condition that she should rule as his colleague in the kingdom. A festival was kept to celebrate this reconciliation, where Cæsar’s barber, a busy, listening fellow, whose excessive timidity made him inquisitive into every thing, discovered that there was a plot carrying on against Cæsar by Achillas, general of the king’s forces, and Pothinus, the eunuch. Cæsar, upon the first intelligence of it, set a guard upon the hall where the feast was kept, and killed Pothinus. Achillas escaped to the army, and raised a troublesome and embarrassing war against Cæsar, which it was not easy for him to manage with his few soldiers against so powerful a city and so large an army. The first difficulty he met with was want of water, for the enemies had turned the canals.

“Another was, when the enemy endeavored to cut off his communication by sea, he was forced to divert that danger by setting fire to his own ships, which, after burning the docks, thence spread on and destroyed the great library. A third was, when in an engagement near Pharos, he leaped from the mole into a small boat, to assist his soldiers who were in danger, and when the Egyptians pressed him on every side, he threw himself into the sea, and with much difficulty swam off. This was the time when, according to the story, he had a number of manuscripts in his hand, which, though he was continually darted at, and forced to keep his head often under water, yet he did not let go, but held them up safe from wetting in one hand, whilst he swam with the other. His boat, in the mean time, was quickly sunk. At last, the king having gone off to Achillas and his party, Cæsar engaged and conquered them. Many fell in that battle, and the king himself was never seen after. Upon this, he left Cleopatra queen of Egypt, who soon after had a son by him, whom the Alexandrians called Cæsarion, and then departed for Syria.”

Caesar in Asia

On his way back to Italy Caesar passed through Asia Minor. Here he found Pharnaces, the son of the great Mithridates, stirring up a revolt in Pontus. At the battle of Zela (47 B.C.) he destroyed the armies of this prince, and restored the Asiatic provinces, recording his speedy victory in the famous words,“Veni, vidi, vici” ( I came, I saw, I conquered). [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Suetonius wrote: “ From Alexandria he crossed to Syria, and from there went to Pontus, spurred on by the news that Pharnaces, son of Mithridates the Great, had taken advantage of the situation to make war, and was already flushed with numerous successes; but Caesar vanquished him in a single battle within five days after his arrival and four hours after getting sight of him, often remarking on Pompeius' good luck in gaining his principal fame as a general by victories over such feeble foemen.”

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Thence he passed to Asia, where he heard that Domitius was beaten by Pharnaces, son of Mithridates, and had fled out of Pontus with a handful of men; and that Pharnaces pursued the victory so eagerly, that though he was already master of Bithynia and Cappadocia, he had a further design of attempting the Lesser Armenia, and was inviting all the kings and tetrarchs there to rise. Cæsar immediately marched against him with three legions, fought him near Zela, drove him out of Pontus, and totally defeated his army. When he gave Amantius, a friend of his at Rome, an account of this action, to express the promptness and rapidity of it, he used three words, I came, saw, and conquered, which in Latin, having all the same cadence, carry with them a very suitable air of brevity. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Hence he crossed into Italy, and came to Rome at the end of that year, for which he had been a second time chosen dictator, though that office had never before lasted a whole year, and was elected consul for the next. He was ill spoken of, because upon a mutiny of some soldiers, who killed Cosconius and Galba, who had been prætors, he gave them only the slight reprimand of calling them Citizens, instead of Fellow-Soldiers, and afterwards assigned to each man a thousand drachmas, besides a share of lands in Italy. He was also reflected on for Dolabella’s extravagance, Amantius’s covetousness, Antony’s debauchery, and Corfinius’s profuseness, who pulled down Pompey’s house, and rebuilt it, as not magnificent enough; for the Romans were much displeased with all these. But Cæsar, for the prosecution of his own scheme of government, though he knew their characters and disapproved them, was forced to make use of those who would serve him.”

Caesar in Africa

Caesar's campaign in North Africa

In 46 B.C.: Caesar defeated Pompey’s remaining followers at Thapsus in North Africa and Caesar became dictator of Rome. The armies of Caesar had now swept over all the provinces of Rome, except Africa. Here the Pompeian leaders, assisted by the king of Numidia, determined to make a last stand against the conqueror. Their forces were under Cato, who held Utica, and Metellus Scipio, who commanded in the field. After subduing a mutiny of his tenth legion by a single word,—calling the men “citizens,” instead of “fellow-soldiers,”—Caesar invaded Africa. The battle of Thapsus (46 B.C.) destroyed the last hope of the Pompeian party. The republican forces were defeated; and Cato, the chief of the senatorial party, committed suicide at Utica. In this war Numidia was conquered and attached to the province of Africa. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “After the battle of Pharsalia, Cato and Scipio fled into Africa, and there, with the assistance of king Juba, got together a considerable force, which Cæsar resolved to engage. He, accordingly, passed into Sicily about the winter-solstice, and to remove from his officers’ minds all hopes of delay there, encamped by the sea-shore, and as soon as ever he had a fair wind, put to sea with three thousand foot and a few horse. When he had landed them, he went back secretly, under some apprehensions for the larger part of his army, but met them upon the sea, and brought them all to the same camp. There he was informed that the enemies relied much upon an ancient oracle, that the family of the Scipios should be always victorious in Africa. There was in his army a man, otherwise mean and contemptible, but of the house of the Africani, and his name Scipio Sallutio. This man Cæsar, (whether in raillery, to ridicule Scipio, who commanded the enemy, or seriously to bring over the omen to his side, it were hard to say,) put at the head of his troops, as if he were general, in all the frequent battles which he was compelled to fight. For he was in such want both of victualling for his men, and forage for his horses, that he was forced to feed the horses with sea-weed, which he washed thoroughly to take off its saltness, and mixed with a little grass, to give it a more agreeable taste. The Numidians, in great numbers, and well horsed, whenever he went, came up and commanded the country. Cæsar’s cavalry being one day unemployed, diverted themselves with seeing an African, who entertained them with dancing and at the same time playing upon the pipe to admiration. They were so taken with this, that they alighted, and gave their horses to some boys, when on a sudden the enemy surrounded them, killed some, pursued the rest, and fell in with them into their camp; and had not Cæsar himself and Asinius Pollio come to their assistance, and put a stop to their flight, the war had been then at an end. In another engagement, also, the enemy had again the better, when Cæsar, it is said, seized a standard-bearer, who was running away, by the neck, and forcing him to face about, said, “Look, that is the way to the enemy.” [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Scipio, flushed with this success at first, had a mind to come to one decisive action. He therefore left Afranius and Juba in two distinct bodies not far distant, and marched himself towards Thapsus, where he proceeded to build a fortified camp above a lake, to serve as a centrepoint for their operations, and also as a place of refuge. Whilst Scipio was thus employed, Cæsar with incredible despatch made his way through thick woods, and a country supposed to be impassable, cut off one party of the enemy, and attacked another in the front. Having routed these, he followed up his opportunity and the current of his good fortune, and on the first onset carried Afranius’s camp, and ravaged that of the Numidians, Juba, their king, being glad to save himself by flight; so that in a small part of a single day he made himself master of three camps, and killed fifty thousand of the enemy, with the loss only of fifty of his own men. This is the account some give of that fight. Others say, he was not in the action, but that he was taken with his usual distemper just as he was setting his army in order. He perceived the approaches of it, and before it had too far disordered his senses, when he was already beginning to shake under its influence, withdrew into a neighboring fort, where he reposed himself. Of the men of consular and prætorian dignity that were taken after the fight, several Cæsar put to death, others anticipated him by killing themselves.

Caesar's final campaign in Spain

“Cato had undertaken to defend Utica, and for that reason was not in the battle. The desire which Cæsar had to take him alive, made him hasten thither; and upon the intelligence that he had despatched himself, he was much discomposed, for what reason is not so well agreed. He certainly said, “Cato, I must grudge you your death, as you grudged me the honor of saving your life.” Yet the discourse he wrote against Cato after his death, is no great sign of his kindness, or that he was inclined to be reconciled to him. For how is it probable that he would have been tender of his life, when he was so bitter against his memory? But from his clemency to Cicero, Brutus, and many others who fought against him, it may be divined that Cæsar’s book was not written so much out of animosity to Cato, as in his own vindication. Cicero had written an encomium upon Cato, and called it by his name. A composition by so great a master upon so excellent a subject, was sure to be in every one’s hands. This touched Cæsar, who looked upon a panegyric on his enemy, as no better than an invective against himself; and therefore he made in his Anti-Cato, a collection of whatever could be said in his derogation. The two compositions, like Cato and Cæsar themselves, have each of them their several admirers.

“Cæsar, upon his return to Rome, did not omit to pronounce before the people a magnificent account of his victory, telling them that he had subdued a country which would supply the public every year with two hundred thousand attic bushels of corn, and three million pounds weight of oil. He then led three triumphs for Egypt, Pontus, and Africa, the last for the victory over, not Scipio, but king Juba, as it was professed, whose little son was then carried in the triumph, the happiest captive that ever was, who of a barbarian Numidian, came by this means to obtain a place among the most learned historians of Greece. After the triumphs, he distributed rewards to his soldiers, and treated the people with feasting and shows. He entertained the whole people together at one feast, where twenty-two thousand dining couches were laid out; and he made a display of gladiators, and of battles by sea, in honor, as he said, of his daughter Julia, though she had been long since dead. When these shows were over, an account was taken of the people, who from three hundred and twenty thousand, were now reduced to one hundred and fifty thousand. So great a waste had the civil war made in Rome alone, not to mention what the other parts of Italy and the provinces suffered.”

Caesar’s Mops Up in Spain and is Heralded in Rome

All resistance to Caesar’s power was now at an end, except a brief revolt in Spain, led by the sons of Pompey, which was soon put down, the enemy being crushed (45 B.C.) at the battle of Munda. Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “He was now chosen a fourth time consul, and went into Spain against Pompey’s sons. They were but young, yet had gathered together a very numerous army, and showed they had courage and conduct to command it, so that Cæsar was in extreme danger. The great battle was near the town of Munda, in which Cæsar seeing his men hard pressed, and making but a weak resistance, ran through the ranks among the soldiers, and crying out, asked them whether they were not ashamed to deliver him into the hands of boys? At last, with great difficulty, and the best efforts he could make, he forced back the enemy, killing thirty thousand of them, though with the loss of one thousand of his best men. When he came back from the fight, he told his friends that he had often fought for victory, but this was the first time that he had ever fought for life. This battle was won on the feast of Bacchus, the very day in which Pompey, four years before, had set out for the war. The younger of Pompey’s sons escaped; but Didius, some days after the fight, brought the head of the elder to Cæsar. This was the last war he was engaged in. The triumph which he celebrated for this victory, displeased the Romans beyond any thing. For he had not defeated foreign generals, or barbarian kings, but had destroyed the children and family of one of the greatest men of Rome, though unfortunate; and it did not look well to lead a procession in celebration of the calamities of his country, and to rejoice in those things for which no other apology could be made either to gods or men, than their being absolutely necessary. Besides that, hitherto he had never sent letters or messengers to announce any victory over his fellow-citizens, but had seemed rather to be ashamed of the action, than to expect honor from it. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Nevertheless his countrymen, conceding all to his fortune, and accepting the bit, in the hope that the government of a single person would give them time to breathe after so many civil wars and calamities, made him dictator for life. This was indeed a tyranny avowed, since his power now was not only absolute, but perpetual too. Cicero made the first proposals to the senate for conferring honors upon him, which might in some sort be said not to exceed the limits of ordinary human moderation. But others, striving which should deserve most, carried them so excessively high, that they made Cæsar odious to the most indifferent and moderate sort of men, by the pretension and the extravagance of the titles which they decreed him. His enemies, too, are thought to have had some share in this, as well as his flatterers. It gave them advantage against him, and would be their justification for any attempt they should make upon him; for since the civil wars were ended, he had nothing else that he could be charged with. And they had good reason to decree a temple to Clemency, in token of their thanks for the mild use he made of his victory. For he not only pardoned many of those who fought against him, but, further, to some gave honors and offices; as particularly to Brutus and Cassius, who both of them were prætors. Pompey’s images that were thrown down, he set up again, upon which Cicero also said that by raising Pompey’s statues he had fixed his own. When his friends advised him to have a guard, and several offered their service, he would not hear of it; but said it was better to suffer death once, than always to live in fear of it. He looked upon the affections of the people to be the best and surest guard, and entertained them again with public feasting, and general distributions of corn; and to gratify his army, he sent out colonies to several places, of which the most remarkable were Carthage and Corinth; which as before they had been ruined at the same time, so now were restored and repeopled together.

“As for the men of high rank, he promised to some of them future consulships and prætorships, some he consoled with other offices and honors, and to all held out hopes of favor by the solicitude he showed to rule with the general good-will; insomuch that upon the death of Maximus one day before his consulship was ended, he made Caninius Revilius consul for that day. And when many went to pay the usual compliments and attentions to the new consul, “Let us make haste,” said Cicero, “lest the man be gone out of his office before we come.”

Roman Triumph by Rubens

Political Moves by Caesar During the Civil War Period

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “With the defeat of the younger Pompey at Munda (near Seville) Caesar had no rival remaining for power at Rome. His action in the wake of his victory confirmed his already established reputation for clemency (clementia), which his heir Octavian (Augustus) would later put forward as a main plank of his propaganda. From the lowliest footsoldier to the most influential politicians, such as Cicero, M. Marcellus, M. Brutus, and C. Cassius, the former adherents of the Pompeian cause were pardoned or recruited. Even Plutarch, who reproduces a startlingly partisan account of Pompey's life and falls in with the standard canard that Caesar lusted after the hated title of king (rex), cannot say otherwise than "... once the civil wars were over, no one could charge him with doing anything amiss. Indeed it is thought perfectly right that the temple of Clemency was dedicated as a thank-offering for his humane conduct after his victory" (Plut. Caes. 57). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Caesar even caused the statues of Pompey, which had been toppled by the people in a first step towards damnatio memoriae, to be re-erected. Late in 49, after driving the Pompeians across the Adriatic, Caesar had been named to the constitutional office of dictator. This he retained only long enough to exercise its power over the holding of consular elections, where naturally he himself was returned as consul for 48. In October of 48, after his victory at Pharsalus in Thessaly, Caesar was named to a second dictatorship, which apparently he preferred to the blatantly illegal expedient of being consul in consecutive years. This time he retained the dictatorship throughout the year (though the ancient precedent set a limit of six months) and no consuls were elected for 47 until near the end of the year, at which point the candidates put forward by Caesar were duly elected; at Rome domestic affairs were under the stewardship of Caesar's magister equitum (master of the horse, the traditional legal name for the dictator's second-in-command) M. Antonius. For 46 Caesar allowed his dictatorship to lapse and again was elected consul, but from this point forward he increasingly disregarded the niceties of constitutional restriction. He was consul in successive years, 46, 45, and up to his death in 44. Together with the consular authority he coupled the powers of the old office of censor, under the title of "prefect of morals"; this was particularly important for Caesar, because ever since the flap over the Roman citizenship of his colony at Novum Comum in Gaul, which the consul Marcellus had flouted in 59 by having one of these "citizens" publicly beaten, his extensions of citizenship (e.g. to the Transpadane Latins, by a Lex Roscia in 49 acc. to Dio 41.36.3, and to his Gallic legion called the Alaudae, acc. to Suet. Jul. 24) had been among the most controversial of his acts. ^*^

“If we look away for a moment from Caesar's constitutional position to the public reforms which followed his victory in the civil war, it is hard to make out the fire-breathing Gracchan popularis of Caesar's early years. He sapped the power of the publicani by assigning the collection of taxes to local municipalities. He limited ex-praetors to a single year and ex-consuls to two years as provincial governors (i.e. military commanders), which seems odd when one recalls what Caesar had had to go through to prolong his own tenure in Gaul; but that was just the point. He outlawed the collegia, which were clubs or syndicates composed of members of the lower classes and often engaged in running protection rackets; this was another startlingly anti-populist measure. He cut the number of those eligible for the dole at Rome by more than half, from 320,000 to 150,000, hardly a populist measure, but also unpopular with the big slave owners, who had gotten into the habit of freeing their slaves, on the condition that they would continue to work for their old masters while being fed at public expense. Indeed, in 45 BC M. (?) Brutus was happily reporting that Caesar had "gone over to the boni ("the good men", i.e. the optimates)" - but Cicero was hardly convinced (ad Att. 13.40). There was also some moderate debt reform involving limits on interest rates and the re-assessment of properties to reflect the recent drop in the value of the Roman currency; these measures pleased neither the radicals, who were calling as usual for a cancellation of debts, nor the conservative optimates like Cicero, for whom property rights were sacred (De. Off. 2. 78).

“Caesar's populist roots come out most strongly in his last years, however, with his foundation of colonies (a form of land distribution). He was able to get away with cutting the dole precisely because most of the men thus deprived became eligible for settlement in his colonies, mostly in the west, Spain, Gaul, and Africa, a few in Greece. All the time he was granting citizenship or rises in citizen status to various individuals and towns (all of Sicily, for example, got the ius Latium 'Latin rights', and incredibly a few romanized Gallic aristocrats were brought into the Senate). For this tendency two interpretations are possible. The descendants of Mommsen, Caesar's most eloquent modern defender, praise his vision for taking this giant step towards making the Roman Empire more inclusive and hence stronger; the detractors, whose name is legion (but Gelzer is prominent among them) say that Caesar was simply increasing his personal clientela. ^*^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024