Home | Category: Age of Caesar

JULIUS CAESAR IN BRITAIN

Caesar invaded Britain twice. His conquests there are regarded as little more than the first steps of Rome’s effort to take over Britain. Britain did become fully Romanized until Emperor Claudius launched a more sustained campaign about a hundred years after Caesar’s invasion and that campaign was completed by Tacitus' father-in-law Agricola.

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “The first Roman to seize the opportunities for glory provided by Britain was Julius Caesar. Having essentially conquered Gaul by 56 B.C., he found himself in a position where he was compelled to return to Rome and disband his army, unless he could find an excuse to stay in the field. He found that excuse in Britain. By claiming that the British tribes had helped the Gauls he had just cause to invade. In fact, as his own writings and the letters he sent to Cicero indicate, he was much more interested in the glory he would gain for crossing the Great Ocean and in the wealth of silver rumoured to be on the island, than in any so-called security risk. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, February 17, 2011|]

in 55 B.C., when Commius, king of the Atrebates, was ousted by Cunobelin, king of the Catuvellauni, and fled to Gaul. Caesar seized the opportunity to mount an expedition on behalf of Commius. He wanted to gain the glory of a victory beyond the Great Ocean, and believed that Britain was full of silver and booty to be plundered.

Professor Konnilyn Feig of Foothill College wrote: “In the first century B.C., Britain was settled by Iron Age societies, many with long-term roots in Britain, and others closely tied to tribes of northern France. Commerce was flourishing, populations were relatively large, and at least seven different British tribes had their own coinages. Tribes in southwest Britain and Wales controlled considerable mineral wealth in tin deposits and copper mines. [Source: Professor Konnilyn Feig, Foothill College, Los Altos, California, Athenapub ***]

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “The first Roman to seize the opportunities for glory provided by Britain was Julius Caesar. Having essentially conquered Gaul by 56 B.C., he found himself in a position where he was compelled to return to Rome and disband his army, unless he could find an excuse to stay in the field. He found that excuse in Britain. By claiming that the British tribes had helped the Gauls he had just cause to invade. In fact, as his own writings and the letters he sent to Cicero indicate, he was much more interested in the glory he would gain for crossing the Great Ocean and in the wealth of silver rumoured to be on the island, than in any so-called security risk. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Caesar in Britain” by Julius Caesar Amazon.com;

“The Conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Greatest Victory: The Battle of Alesia, Gaul 52 BC” by John Sadler, Rosie Serdiville (2016) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Army: the Evolution, Composition, Tactics, Equipment & Battles of the Roman Army” by Harry Pratt Judson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics Hardcover) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“Julius Caesar” by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library) Amazon.com;

“Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (2003) Amazon.com

“The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works : Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War : in One Volume, with Maps, Annotations, Appendices, and Encyclopedic Index” by 2017) Amazon.com

Caesar's Invasions of Britain

“His first expedition, however, was ill-conceived and too hastily organised. With just two legions, he failed to do much more than force his way ashore at Deal and win a token victory that impressed the senate in Rome more than it did the tribesmen of Britain. In 54 B.C., he tried again, this time with five legions, and succeeded in re-establishing Commius on the Atrebatic throne. Yet he returned to Gaul disgruntled and empty-handed, complaining in a letter to Cicero that there was no silver or booty to be found in Britain after all.” |::|

By the time of the second expedition in 54 B.C. “he had received the accolades he desired and ...pulled out of the island, exacting tribute and hostages and concentrated on pacifying the troublesome tribes of Gaul before crossing the Rubicon with his army and returning to Rome as its most powerful son. His power and prestige were so great, in fact, that his enemies were forced to assassinate him, sparking the civil war that destroyed the Republic. |::|

“Caesar's military adventurism set the scene for the second exploitation of Britain - by the Emperor Claudius. He was to use an identical excuse to Caesar for very similar reasons. Claudius had recently been made emperor in a palace coup. He needed the prestige of military conquest to consolidate his hold on power. Into this situation came Verica, successor to Commius, complaining that the new chief of the Catuvellauni, Caratacus, had deprived him of his throne. |::|

Plutarch on Caesar in Britain

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “In the passage of his army over it he met with no opposition; the Suevi themselves, who are the most warlike people of all Germany, flying with their effects into the deepest and most densely wooded valleys. When he had burnt all the enemy's country, and encouraged those who embraced the Roman interest, he went back into Gaul, after eighteen days' stay in Germany. But his expedition into Britain was the most famous testimony of his courage. For he was the first who brought a navy into the western ocean, or who sailed into the Atlantic with an army to make war; and by invading an island, the reported extent of which had made its existence a matter of controversy among historians, many of whom questioned whether it were not a mere name and fiction, not a real place, he might be said to have carried the Roman empire beyond the limits of the known world. He passed thither twice from that part of Gaul which lies over against it, and in several battles which he fought did more hurt to the enemy than service to himself, for the islanders were so miserably poor that they had nothing worth being plundered of. When he found himself unable to put such an end to the war as he wished, he was content to take hostages from the king, and to impose a tribute, and then quitted the island. At his arrival in Gaul, he found letters which lay ready to be conveyed over the water to him from his friends at Rome, announcing his daughter's death, who died in labour of a child by Pompey. Caesar and Pompey both were much afflicted with her death, nor were their friends less disturbed, believing that the alliance was now broken which had hitherto kept the sickly commonwealth in peace, for the child also died within a few days after the mother. The people took the body of Julia, in spite of the opposition of the tribunes, and carried it into the field of Mars, and there her funeral rites were performed, and her remains are laid. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

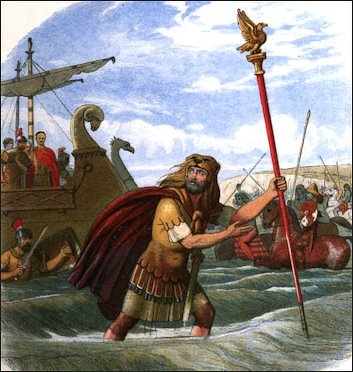

Standard-bearer of the Tenth Legion

“Caesar's army was now grown very numerous, so that he was forced to disperse them into various camps for their winter quarters, and he having gone himself to Italy as he used to do, in his absence a general outbreak throughout the whole of Gaul commenced, and large armies marched about the country, and attacked the Roman quarters, and attempted to make themselves masters of the forts where they lay. The greatest and strongest party of the rebels, under the command of Abriorix, cut off Cotta and Titurius with all their men, while a force sixty thousand strong besieged the legion under the command of Cicero, and had almost taken it by storm, the Roman soldiers being all wounded, and having quite spent themselves by a defence beyond their natural strength. But Caesar, who was at a great distance, having received the news, quickly got together seven thousand men, and hastened to relieve Cicero. The besiegers were aware of it, and went to meet him, with great confidence that they should easily overpower such a handful of men. Caesar, to increase their presumption, seemed to avoid fighting, and still marched off, till he found a place conveniently situated for a few to engage against many, where he encamped. He kept his soldiers from making any attack upon the enemy, and commanded them to raise the ramparts higher and barricade the gates, that by show of fear they might heighten the enemy's contempt of them. Till at last they came without any order in great security to make an assault, when he issued forth and put them in flight with the loss of many men.

“This quieted the greater part of the commotions in these parts of Gaul, and Caesar, in the course of the winter, visited every part of the country, and with great vigilance took precautions against all innovations. For there were three legions now come to him to supply the place of the men he had lost, of which Pompey furnished him with two out of those under his command; the other was newly raised in the part of Gaul by the Po. But in a while the seeds of war, which had long since been secretly sown and scattered by the most powerful men in those warlike nations, broke forth into the greatest and most dangerous war that was in those parts, both as regards the number of men in the vigour of their youth who were gathered and armed from all quarters, the vast funds of money collected to maintain it, the strength of the towns, and the difficulty of the country where it carried on. It being winter, the rivers were frozen, the woods covered with snow, and the level country flooded, so that in some places the ways were lost through the depth of the snow; in others, the overflowing of marshes and streams made every kind of passage uncertain. All which difficulties made it seem impracticable for Caesar to make any attempt upon the insurgents. Many tribes had revolted together, the chief of them being the Arverni and Carnutini; the general who had the supreme command in war was Vergentorix, whose father the Gauls had put to death on suspicion of his aiming at absolute government.

Caesar’s Landings in Britain

Caesar's invasion of Britain

“For this period, Caesar is the only extant source providing first-hand descriptions of Britain. His observations, while confined to the southeast areas of Kent and the lower Thames, are thus essential to understanding those regions. While no doubt self-serving in a political sense when written, Caesar's account is nevertheless regarded as basically accurate and historically reliable both by earlier scholars such as C. Rice Holmes (1907), and by today's authorities including Sheppard Frere (1987). ***

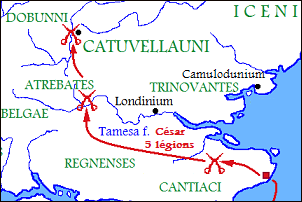

“Both the 55 and 54 B.C. Roman expeditions left from Boulogne (Portus Itius), and landed at Deal, a few miles northeast of Dover. In 55 B.C., the Roman cavalry ships were forced back to Gaul by a storm, and Caesar's troops were confined to the shore. In 54 B.C., a larger Roman expedition landed at Deal and penetrated inland along the River Thames.” After that they left. The Romans did “not to return again for 97 years, when the Claudian invasion of A.D. 43 began the active Roman conquest of Britain. Caesar's two expeditions, meanwhile, provided basic information on the terrain, inhabitants, and political, economic and military customs of Britain, our only direct historical record for that time period.” ***

Where Did Caesar's Landings in Britain Take Place?

The exact locations of Caesar’s landings have been debated. Deal Beach — a beach made up of small stones or shingles near Walmer Castle in Kent — is may have been in the area where Julius Caesar and his troops landed during the two Roman excursions to Britain of 55 and 54 B.C. From there the cliffs of Dover can seen to the south In the distance.

Evidence revealed in 2018 suggests that one landing occurred at Ebbsfleet, at the Isle of Thanet in eastern Kent. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: During construction of a modern road, workers discovered a large ancient ditch measuring around 15 feet wide and six feet deep. Objects found nearby, including Roman weapons, indicated that it was constructed around the middle of the first century B.C., and its size and shape are consistent with Roman defensive networks of that era. Archaeologists believe that Caesar’s army built a temporary fort at the site to protect his fleet of 800 ships. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2018]

“The wider significance of the discoveries at Ebbsfleet is to refocus attention on the aftermath of Caesar’s invasions,” says University of Leicester archaeologist Andrew Fitzpatrick. “Caesar never intended to stay in Britain,” he adds, “but we theorize that the peace treaty he concluded then paved the way for the eventual invasion and permanent occupation of the Romans in A.D. 43.”

First Roman Landing in Britain in 55 B.C.

Professor Konnilyn Feig wrote: “Caesar probably planned an expedition to Britain in 56 B.C., a year when the Armorican tribes in the coast of Britanny revolted against the Romans with aid from the tribes of southern Britain. The operation was further delayed by battles with the Morini and Menapi, Belgic tribes who controlled the Straits of Dover. [Source: Professor Konnilyn Feig, Foothill College, Los Altos, California, Athenapub ***]

“Finally, on August 26, 55 B.C., two Roman Legions (about 10,000 soldiers) under Caesar's personal command crossed the channel in a group of transport ships leaving from Portus Itius (today's Boulogne). By the next morning (August 27), as Caesar reports, the Roman ships were just off the chalky cliffs of Dover, whose upper banks were lined with British warriors prepared to do battle. The Romans therefore sailed several miles further northeast up the coastline and landed on the flat, pebbly shore around Deal. ***

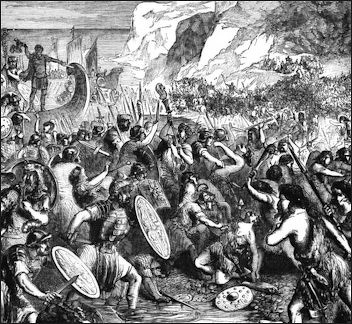

“The Britons met the legionaries at the beach with a large force, including warriors in horse-drawn chariots, an antiquated fighting method not used by the Roman military. After an initial skirmish, the British war leaders sought a truce, and handed over hostages. ***

“Four days later, however, when Roman ships with 500 cavalry soldiers and horses also tried to make the channel crossing, they were driven back to France by bad weather. The same storm seriously damaged many of the Roman ships on the beach at Deal. This quirk of fate resulted in Caesar's initial landing force having no cavalry, which seriously restricted the mobility of the 55 B.C. operations. It was also disastrous for the planned reconnaissance since the legionary soldiers were forced to repair the ships and were vulnerable to the British forces who began new attacks. ***

“Thus immobilized, the Roman legions had to survive in a coastal zone which they found both politically hostile, and naturally fertile. The need to procure food locally resulted in scouting and foraging missions into the adjacent countryside. Caesar reports abundant grain crops along a heavily populated coastline; and frequent encounters with British warriors in chariots. After repairing most of the ships, Caesar ordered a return to Gaul, thus curtailing the reconnaissance of 55 B.C.” ***

Caesar on His Invasion of Britain in 55 B.C.

Caesar invaded Britain in 55 B.C. partly in hope of "getting pearls." Describing the invasion Caesar wrote: "The Romans were faced with grave difficulties. The size of the ships made it impossible to run them aground except in fairly deep waters and the soldiers, unfamiliar with the ground, with their hands full, and weighed down by the heavy burden of their arms, had at the same time to jump down from the ships, get a footing in the waves, and fight the enemy." [Source: Eyewitness to History, edited by John Carey, 1987, Avon Books]

“The enemy, who, standing on dry land or advancing only a short way into the water, fought with all their limbs unencumbered and on preferably familiar ground, boldly hurling javelins and galloping their horses, which were trained for this kind of work. These perils frightened our soldiers, who were quite unaccustomed to battles of this kind, with the result that they did not show the same alacrity and enthusiasm as they usually did in battles on dry land."

"Seeing this, Caesar ordered the warships — which were swifter and easier to handle than the transports, and likely to impress the natives more by their unfamiliar appearance — to be removed a short distance from the others, and then to be rowed hard ashore on the enemy's right flank, from which position slings, bows, and artillery could be used by men on deck to drive them back."

"The maneuver was highly successful. Scared by the strange shape of the warships, the motion of the oars, and the unfamiliar machines, the natives halted and then retreated a little. But as the Romans hesitated, chiefly on account of the depth of the water, the man who carried the eagle of the tenth legion, after praying to the gods that his actions might bring good luck to the legion, cried in a loud voice, 'Jump down comrades, unless you want to surrender our eagle to the enemy; I, at any rate, mean to do my duty to my country and general.'"

"With these words he leapt out of the ship and advanced towards the enemy with the eagle in his hands. At this the soldiers, exhorting each other not to submit to such a disgrace, jumped with one accord from the ship, and the men from the next ships, when they saw them, followed them and advanced against the enemy."

Second Roman Expedition to Britain in 54 B.C.

Professor Konnilyn Feig of Foothill College wrote: “The next year saw the Romans organize a much larger expedition to Britain, with a total of 800 ships used to transport five legions and 2000 cavalry troops, plus horses and a large baggage train. They sailed from Boulogne at night on July 6, and landed unopposed the next day on the beach between Deal and Sandwich. [Source: Professor Konnilyn Feig, Foothill College, Los Altos, California, Athenapub ***]

“Upon seeing the large size of the Roman force, the Britons retreated inland to higher ground. Caesar immediately marched inland with most of his troops to the Stour River, about 12 miles from the beach landing camp. At daybreak on the 8th of July, 54 B.C., the Romans encountered British forces at a ford on the Stour (later the town of Canterbury). The Romans easily dispersed the Britons, who retreated to a hill fort or stronghold (oppidum), which from Caesar's description, is probably the hill fort at Bigbury, a site with earthwork and ditch enclosures mile and a half from the river ford. The Seventh Roman legion attacked the hillfort but were blocked out by trees piled in the entrance by the Britons. To advance, the Roman troops filled in the outer ditch with earth and brush, making a ramp across it, and then capturing the fort. ***

“Bad news came for the Romans, however, shortly thereafter from the beach camp at Deal. An overnight storm had driven most of the Roman ships on shore. The main body of troops returned to the beach, to find at least forty boats completely wrecked. Security precautions required Caesar's army to spend ten long days building a land fort within which the entire fleet of 760 ships was transported. This, the second catastrophe for Roman ships in as many years caused by storms on the open beach, could have been averted had Caesar sailed only a few miles further up the coast to the protected harbor at Richborough (where the Romans landed when they next invaded Britain, in 43 AD). ***

Caesar's Campaign in Britain “During this ten day hiatus, a large British force was briefly united under a single commander, Cassivellaunus, who ruled the Catuvellauni tribe on the north side of the River Thames. The army of Cassivellaunus met the Romans again at the Stour crossing. The Britons used chariot warfare, with two horses pulling a driver and warrior, the latter hurling javelins, then dismounting at close quarters to fight infantry-style. After a hard-fought battle, the Romans eventually drove back the Britons, and then pursued Cassivellaunus toward the Thames. ***

“In the wooded terrain north of the River Thames, Cassivellaunus adopted scorched-earth, guerrilla-warfare methods, destroying local food sources and using chariots to harrass the Roman legions. But neighboring tribes who resented the domination by Cassivellaunus, including the Trinovantes and their allies the Cenimagni, Segontiaci, Ancalites, Bibroci and Cassi (the latter five tribes, known to us only through Caesar's account) then went over to the Romans. ***

“Caesar thus learned from native informants the location of the secret stronghold of Cassivellaunus, probably the hill fort at Wheathampstead, located on the west bank of the River Lea, near St. Albans. Even as the Roman army under Caesar were massing outside his fort's gates, however, Cassivellaunus made the bold move of ordering his allies in Kent to attack the Roman beach camp at Deal. This attack failed, and Cassivellaunus then gave up. Yet the terms of surrender he negotiated with the Romans seem to have been moderate, as Caesar had learned of mounting problems back in Gaul, and wanted to return there. The Roman legions left Britain in early September, 54 B.C.” ***

Trinovantes and Catuvellauni

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “Camulodunum (present-day Colchester) was a hugely important site in pre-Roman times. It was most likely the royal stronghold of the Trinovantes, on whose behalf Julius Caesar invaded in 55 and 54 B.C. At this time, the Catuvellauni under their king Cassivellaunus were spreading their authority as southern Britain's largest tribe across the south-eastern counties. It seems that Cassivellaunus invaded Trinovantian territory and murdered its king, whose son, Mandubracius, fled to Caesar for help. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Trinovantes and Catuvellauni

“This gave Caesar the excuse he was looking for to invade, and after a botched attempt in 55 (which even his own propaganda cannot quite disguise), Caesar returned to finish the job in 54 B.C. He chased Cassivellaunus back to his stronghold, which he stormed from two sides, forcing Cassivellaunus to flee and come to terms. |::|

“It is a moot point where this encampment was. Our best guess is Wheathamstead, Herts, but it is possible (though I do not think probable) that Cassivellaunus had transferred his capital to Camulodunum. Part of the problem is one of dating, since we do not know when Camulodunum came into Catuvellaunian hands. Our best dating criteria are by coins, but the earliest coins in the area are for the Catuvellaunian king, Tasciovanus, who ruled c.25-15 B.C. By c.AD 10, Cunobelin the nephew of Cassivellaunus, had taken over the area and his coinage reflects this. |::|

“The last Trinovantian king was called Addedomaros. It is possible that his remains are buried in the Lexden Tumulus, close to Gosbecks. The king who was buried here had been ritually burned along with his goods, which were a mixture of Celtic and Roman ornaments. Among them were the fragments of a small casket, within which was a medallion bearing the head of the Emperor Augustus.” |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024