Home | Category: Culture and Sports

CHARIOT RACING IN ANCIENT GREECE

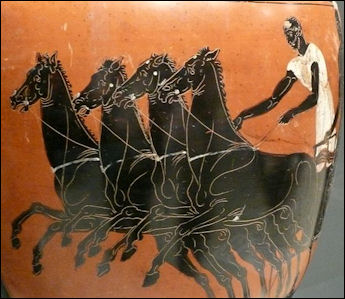

Racing with four full-grown horses was always most popular, but there were also races with two-horse chariots and with colts. The principal feature of the Olympic games from the year 680 B.C. was the chariot race for four horses, and a victory in this event brought much-coveted renown to the owner of the horses and his city. The Greeks of Italy and Sicily were devoted to this sport, their interest being reflected in their coin types, of which the finest are the Syracusan.

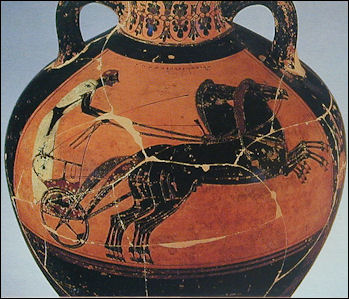

A very beautiful bronze statue found at Delphi, no doubt a dedication after a victory, represents a young charioteer in the long white chiton which was his traditional dress and a fragment of a relief from the Mausoleum shows another with flying hair and garment as he strains forward toward the goal. One of the Panathenaic amphorai was a prize in a chariot race at Athens, as we know from the drawing on one side. Another event in the games at Athens was a race for two horses harnessed to a little cart in which the driver sat, but this contest was never so important as the race for four horses. At other games the chariot was the vehicle used for two horses as well as for four. These sports were naturally very costly, and under the Roman rule they gradually died out in Greece as races in the circus in Rome and other Italian cities took their place. Chariot races were the earliest of the free shows at Rome and were always the most popular, the great attraction of the circus being not the speed of the race, but its danger. Some clay lamps from Cyprus are decorated with reliefs of chariots and horses, showing how the passion for racing spread over the Roman world.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“On Horsemanship” by Xenophon Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

Chariot Racing in the Ancient Olympics

Chariot races with four full-grown horses was added to the Olympics in 680 B.C. In 408 B.C. the chariot race with two horses was introduced. Chariot racing was among the biggest draws at the ancient Olympics. During the races spectators were sometimes killed after they ran onto the track.

The Olympic games often kicked off with a race involving 40 chariots flying through a course at one time with spectacular spills and frequent deaths. Often only a handful of the chariots that started made it to the finish line. Chariots had to make 12 laps around the track, totalling around 13,500 meters. Competitors were often killed. Describing an accident Sophocles wrote: “As the crowd saw the driver somersault, there rose a wail of pity for the youth as he was bounced onto the ground , then flung head over heels into the sky. When his companions caught the runaway team and freed the bloodstained corpse from his reigns he was disfigured and marred past the recognition of his best friend.”

The Cuadriga was a charriot with a wood and metal carriage pulled by four horses. They were usually driven by hired professional, essentially slaves, owned by the sponsors. They lived in stables and were breed like horses from the offspring of famous charioteers. Despite their lowly background successful charioteers were celebrated heroes and the best ones earned enough money to buy their freedom. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

Horse Racing in the Ancient Olympics

Horse races were added to the Olympics in 648 B.C. Attempts were made to introduce mules and mares, but these were soon abandoned; colts were, however, introduced for the contest with four and two horses, and also for riding. Awards were often given to the owners not the riders. When the riders were recognized both the horse and the rider were given wreaths. Equestrian sports were among the few events that women and girls were allowed to compete in.

Horse races were added to the Olympics in 648 B.C. Attempts were made to introduce mules and mares, but these were soon abandoned; colts were, however, introduced for the contest with four and two horses, and also for riding. Awards were often given to the owners not the riders. When the riders were recognized both the horse and the rider were given wreaths. Equestrian sports were among the few events that women and girls were allowed to compete in.

There were other horse sports. One of the marque events at Greek festivals was the “apobates” , in which contestant in full armor leapt on and off moving chariots. There were also horseback riding events in which riders rode bareback and naked and mule cart races.

Riding races became extremely popular, although they never attained the great importance claimed by the chariot races in the Olympic games. In both contests it was the trainer of the horse who was regarded as victor, and though it sometimes happened that the owner or his son drove or rode himself, yet it was more commonly done by strangers, very often by professional charioteers and riders hired for the purpose, like our jockeys of the present day. Instead of the wreath, which was not allotted to them, they received a fillet as a token of victory. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Hippodromes in Ancient Greece

Chariot and horse races were held in long, narrow Hippodromes that seated up to 45,000 spectators. The hippodrome was the largest monument at the Olympia site, but there were no remains. It was believed that the terraces could accommodate more than 30,000 spectators. Walls divided the track.

The track was not like a modern horse racing track. It was more like an oval football field with a row of columns down the middle, which created a lot of maneuvering room. The Hippodrome in Olympia is completely destroyed, and all the knowledge we possess of its situation is due to Pausanias, who gives us no information concerning the length of the course to be run twice by full-grown horses.

However, he supplies a detailed description of the starting places, which were very complicated, since no competitor must have an advantage over another by starting earlier or having a shorter piece of ground to cover. For this purpose the two long sides of the Hippodrome were of unequal length, and the one at the end of which were the goal and the seats of the judges was rather shorter than the other; the stands for the chariots were not in a straight line, but in the form of the segment of a circle.

How Ancient Olympic Chariot Races Were Conducted

Chariots were positioned at different distances from each other. They started in a staggered fashion so that those on the outside were not at a disadvantage. Those furthest from the front started first. When the first chariots reach the next, they also started to move. The process was repeated for the next chariots, with all reaching the entrance to the track together and begin to race.

The aphesis, the interesting start system for the chariots in the race, was apparently designed to prevent the chariots from colliding with each other right after starting, and to allow a rolling start as they enter the racetrack at the same time, providing a more balanced start for all participants. Under Aphesis starting system. The chariots were placed spaced apart from each other in different positions on a V-shaped base, like a formation of geese in the sky. The chariots depart in reverse order, with the chariots furthest from the apex being the first to leave, and so on, until the last chariots to depart were those at the tip of the V.

"A two-wheeled chariot," wrote journalist Lionel Casson in Smithsonian magazine, "was light, like a modern trotters' gig, but pulled by a team of four horses that would be driven at the fastest gallop they could generate. They made 12 laps around the course — about nine kilometers — with 180 degree turns at each end. As at our Indianapolis 500 viewers enjoyed not only the excitement of the race but the titillation that comes from the constant presence of danger: as the teams thundered around the turns, or one chariot tried to cut over from the outside to the inside, crashes and collisions were common and doubtless often fatal. In one celebrated race in the Pythian games, the competition was so lethal that only one competitor managed to finish!" [Lionel Casson, Smithsonian, February 1990]

Four-Horse Ancient Olympic Chariot Race

The four-horse chariots races were regarded as one of the most spectacular. They employed for the purpose the light two-wheeled chariots used in battle in the heroic age; these had, as a rule, wheels with four spokes, and the car was open at the back and closed in a semi-circular shape in front, with two bent hoops turned back behind, which were used to catch hold of in jumping up. Here we see the preparations for driving; the charioteer, clad in a long garment according to ancient custom, stands behind the two horses, which are yoked to the chariot, and seems about to complete the arrangement of the harness, while an attendant in a short garment is helping him; another attendant leads a third horse, which is probably also to be yoked to the chariot; while the owner holds in his hand the reins and the goad with which to urge on the horses. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The usual plan was to fasten the middle horse to a yoke at the end of the pole which is raised in front, while the outer horses were connected with ropes at either side, fastened to a ring in front of the chariot. The reins were all drawn through a ring or loop at the top of the pole, and the pin on to which this ring was fastened was connected with a vertical rod in front of the chariot by a line drawn very tight, the object of which is not clear; perhaps it was to establish equilibrium between the car, which was drawn backwards by the weight of the driver, and the forward pressure given to the pole by the pull of the horses. This picture also shows other details of harnessing, the bridle, etc.

The ropes, which prevented the chariots from starting before the appointed time, did not all drop at the same moment, but one after another in such a way that the chariots started first from the more distant stands, and reached a given point at the same time as those from the nearer stands, which started a few seconds later, so that the racing began at this place under equal conditions.

The signal was given by the sound of trumpets, and also by some ingenious mechanism which caused a bronze dolphin on an elevated place at the beginning of the course to fall, while an eagle, which till then had rested on an altar, rose into the air with extended wings. At this sign the barriers fell, and the chariots started in the appointed order over the longer side of the course, and then, turning back, returned by the shorter side. This was the exciting contest which has been so magnificently described by Homer in his account of the funeral games in honour of Patroclus, and by Sophocles in the “Electra.” The victor who first reached the goal, near which sat the umpires, received the much-coveted reward of a wreath; but even the next seems to have had some distinction or, at any rate, an honourable mention.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024