Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory

TRYING TO READ THE HERCULANEUM PAPYRI

Herculaneum Scroll unraveled

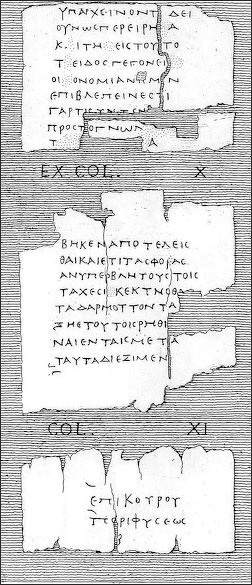

In the 1750s excavators recovered 1,500 papyri from the Villa dei Papiri. Today these are are generally referred to as the Herculaneum Scrolls or Herculaneum papyri. Attempts to unroll them did more harm than good. In some case they were cut and split open, resulting in thousand of poorly labeled fragments, which got further messed up when they were moved to the Museum of Naples. Since then the fragments have been joined together using syntax matches between pages and numbers jotted by 19th century copyists on the fragments and figuring out the number system devised by the 18th century scholars who tore the documents apart.

The Herculaneum Papyri scrolls were discovered in 1752 by a farmer after being buried almost 27 meters (90 feet) under volcano rock in the Villa dei Papiri. At first, most of the charred scrolls were thought to just be charcoal. It was only when someone noticed the faint trace of letters that the breadth of historical knowledge trapped under carbonised papyrus was recognised.

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: At least eight hundred scrolls were uncovered; they constitute the only sizable library from the ancient world known to have survived intact. Some were found stacked on shelves in a small room; others were elsewhere in the villa, packed in capsae, travelling boxes for the scrolls, presumably in preparation for flight. Given the splendor of the villa, and the masterly bronze sculptures found in its ruins, the learned world assumed that the library would contain vanished classics. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “In trying to read the scrolls, scholars and curators have invariably damaged or destroyed them. The Herculaneum papyri survived only because all the moisture was seared out of them—uncharred papyrus scrolls in non-desert climates have long since rotted away. In each scroll, the tightly wrapped layers of the fibrous pith of the papyrus plant are welded together, like a burrito left in the back seat of a car for two thousand years. But, because the sheets are so dry, when they are unfurled they risk crumbling into dust. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“During the past two hundred and fifty years, an array of methods and materials have been used on the easier-to-unwrap scrolls, including rose water, mercury, “vegetable gas,” sulfuric compounds, and papyrus juice—most of which have caused grievous harm to the delicate plant material on which the text is inscribed. Scores of scrolls have been badly damaged or destroyed, ruined by the same uniquely human impulse that went into making them—the desire to read. \=/

RELATED ARTICLES:

HERCULANEUM SCROLLS: HISTORY AND EFFORTS TO UNWRAP THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ERUPTION OF VESUVIUS IN A.D. 79: EFFECTS, EARTHQUAKES AND PLINY THE ELDER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM VICTIMS: THEIR LIVES, DEATHS AND VAPORIZATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, BUILDINGS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POMPEII: HISTORY, BUILDINGS, INTERESTING SITES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POMPEII ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Library of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by David Sider (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum: Archaeology, Reception, and Digital Reconstruction” by Mantha Zarmakoupi, (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Presocratics at Herculaneum: A Study of Early Greek Philosophy in the Epicurean Tradition. With an Appendix on Diogenes of Oinoanda's Criticism of Presocratic Philosophy”

by Christian Vassallo (2021) Amazon.com;

“Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by Kenneth Lapatin (2019) Amazon.com;

“Herculaneum: Italy's Buried Treasure” by Joseph Deiss (1989) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Alison E. Cooley (2013) Amazon.com;

“Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Paul Roberts Amazon.com;

"Pompeii's Living Statues: Ancient Roman Lives Stolen from Death” by Eugene Dwyer | (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pompeii”, Illustrated, by Joanne Berry (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (1996) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: An Archaeological Guide by Paul Wilkinson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Inside Pompeii”, a photographic tour, by Luigi Spina (2023) Amazon.com;

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

“Vesuvius: A Biography” by Alwyn Scarth (2009) Amazon.com;

“Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei, and Campanian Volcanism” by Benedetto De Vivo, Harvey E. Belkin, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Neapolitan Volcanoes: A Trip Around Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei and Ischia” (GeoGuide)

by Stefano Carlino (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Eruption of Vesuvius in 1872: Unveiling the Catastrophic Fury of Mount Vesuvius”

by Luigi Palmieri and Robert Mallet (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius” by Pedar W. Foss Amazon.com;

“The Letters of the Younger Pliny (Penguin Classics) by Pliny the Younger and Betty Radice (1963) Amazon.com;

“Ghosts of Vesuvius: A New Look at the Last Days of Pompeii, How Towers Fall, and Other Strange Connections” by Charles R Pellegrino (2005) Amazon.com;

Daniel Delattre: Papyrologist Determined to Read the Herculaneum Papyri

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: Daniel Delattre, a distinguished French papyrologist, learned Latin by the age of eleven and ancient Greek a few years after that. “Those were the two subjects I preferred,” he told me. He met his wife, Joëlle Delattre-Biencourt, in high school, and they fell in love with antiquity and with each other. After attending the University of Lille, Delattre taught high-school classics and began working on his doctoral thesis, on the theology of Epicurus, who is best known for the doctrine that the goal of life is pleasure. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“Delattre didn’t plan to become a papyrologist, but one of the Philodemus scrolls unwrapped by Father Piaggio in the eighteenth century was on the subject of Epicurus and the gods, and he wanted to read it. He went to the National Library in Naples. “When I saw the opened sheets of carbonized papyrus for the first time, it was very impressive. For me, the writing was very vivid. I felt I was in direct contact with that time. And when I read the name Plato for the first time in the text it made me very emotional. I became a papyrologist at that moment.” \=/

“Delattre spent a year in the National Library, where, in addition to his thesis research, he started working on a new edition of part of Philodemus’ “On Music, Book 4,” the first of the scrolls opened with Piaggio’s machine. That was in 1985. He finished two decades later. Along the way, he made a stunning discovery: previous editions of “On Music” had the sequence of some of the detached leaves of the scroll backward. Delattre’s edition, published in 2007, corrected the problem and has caused papyrologists to reëvaluate the entire Philodemus canon. Richard Janko, in a review in the Journal of Hellenic Studies, called it “pioneering work of the first order.” \=/

“Delattre became the official editor of the six scrolls in the Institut de France in 2003, a year after the two damaged scrolls returned from Naples. Working at the Sorbonne and at the Institut de France, he has been preparing an edition of one of them, assisted by various students and colleagues; his wife, a retired philosophy professor, is also part of the team. Delattre has been trying to figure out the correct order of the pieces, read them, and publish an edition before he dies, a goal that he says is impossible, because the project “takes an infinite time. Our human scale is not the scale of the scrolls.” He is far enough along in the book to be sure that it is yet another work by Philodemus: “On Slander.” \=/

current state of many of the Herculaneum scrolls

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “Delattre’s dream has been to recover something of the lost works of Epicurus (341-270 B.C.), the Greek philosopher whose thought has been the focus of his life’s study, and whose writings are known only through secondary sources.” At the library of the Institut de France, which includes the Académie Française, the 68-year-old Delattre, “was contemplating a small wooden box on the table in front of him which was labelled “Objet Un.”... An ornately hand-lettered card was taped to the outside. It said, in French, “Box containing the remains of papyrus from Herculaneum”. \=/ [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“Before addressing Objet Un, Delattre opened another box, containing pieces of two scrolls (the institute has six altogether) that had suffered a misguided attempt to read them in 1985. There were hundreds of fragments, organized within a set of smaller boxes. They resembled scraps of dried mud. But if you looked closely you could see tiny Greek letters on the warped surfaces, made by a scribe two thousand years ago—an electrifying jolt of handwritten human communication from the ancient world. \=/

“Delattre explained that the two ill-fated scrolls had been transported to Naples, where they were treated with a mixture of ethanol, glycerin, and warm water, which was supposed to loosen the folds. One scroll was peeled apart into many fragments; the other dried up and then, like a disaster in slow motion, split apart into more than three hundred pieces. “Well,” Delattre murmured, “it simply exploded.” He shook his head sadly. Delattre placed his hands on the box containing Objet Un. But he did not open it. He prepared his guests for the worst—the shock of seeing the body in the morgue. When he finally lifted the lid, you saw why. Swaddled in thick cotton was what appeared to be a human turd. \=/

“Virtually Unwrapping” the Herculaneum Papyri

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “One glance at the scroll was enough to be sure there was no hope it could ever be unwrapped physically. But what about virtually?... In 2005, Delattre attended a meeting in Oxford of the Friends of Herculaneum Society, a group of professional papyrologists and amateur Herculaneum enthusiasts. The keynote speaker was Brent Seales, a software engineer who is the head of the computer-science department at the University of Kentucky. He gave a talk about the possibility of “virtually unwrapping” the scrolls, using a combination of molecular-level X-ray technology, spectral-imaging techniques, and software designed by him and his students at the university. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“Digital restoration—the application of modern imaging technology to the reading of ancient manuscripts—is not exactly Seales’s idea, but it has become his mission. His work has brought him renown in papyrological circles, and has made him something of a celebrity on campus in Lexington, where the school newspaper regularly reports on his progress. Seales does much of his manuscript work at the university’s Center for Visualization and Virtual Environments, where he is the director. “The idea is that you’re not just conserving the image digitally—you can actually restore it digitally,” Seales explained, in his earnest, go-getter way. The potential struck him in 1995, when he was assisting Kevin Kiernan, an English professor, on a digital-imaging project involving the only extant copy of “Beowulf,” the medieval masterwork, which is in the British Library. The manuscript was damaged in a fire in 1731. The Kentucky team used a variety of techniques, including one called multispectral imaging, or MSI—developed by NASA for use in mapping mineral deposits during planetary flyovers—to make the letters stand out from the charred background. The basic principle is that different surfaces reflect light differently, especially in the infrared part of the spectrum. Inked letters will therefore reflect at different wavelengths from those of the parchment or vellum or papyrus they are written on. \=/

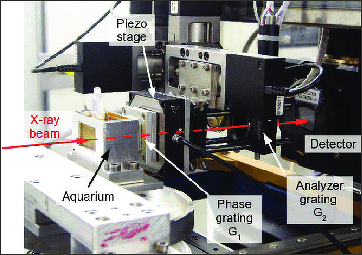

X-ray flourescence machine

“As Seales worked on more manuscripts, he realized that what he had thought of as a two-dimensional problem was really three-dimensional. As a writing surface ages, it crinkles and buckles. If Seales could design software that reverse-engineered that aging process with an algorithm—“something like the stuff that lets you see the flag waving in reverse,” as he put it—he might be able to virtually flatten the manuscript. Back in Kentucky, Seales and his team put their concept to the test with King Alfred the Great’s Old English translation of “The Consolation of Philosophy,” by Boethius, which is also in the British Library. They studied the material science of the vellum that the medieval scribe had used, and, by modelling that on the computer, Seales was able to virtually smooth out the manuscript, making some letters visible for the first time. \=/

“Seales’s name got around to the curators of collections containing badly damaged manuscripts; he was the guy who could read the unreadable. “I came to think of it as the ‘impossible scenario,’ ” he said. “Every time we’d go to a collection, people would pull out stuff they couldn’t do anything with, and say, ‘O.K., you can do something with that, but what about this?’ ” \=/

“Richard Janko, a classical scholar at the University of Michigan and a leading papyrologist, heard of Seales’s work and talked to him about the Herculaneum papyri—the ultimate impossible scenario, because reading them meant not only flattening deformed surfaces but also seeing inside scrolls that had never been unwrapped at all. In 1999 and 2000, a team from Brigham Young University had, in fact, conducted an MSI study on some of the scrolls that had already been opened. They achieved spectacular results on the surfaces. But they could do nothing with the hundreds of scrolls that hadn’t been unrolled. \=/

CT Scans of the Herculaneum Papyri

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “Seales, in his Oxford talk, proposed putting an unopened scroll inside a CT scanner. CT—computed tomography—is the X-ray technology used to create 3-D images of human bones and organs. More recently, CT has been applied to mummies and a variety of other archeological artifacts, as well as to fossils. Because X rays pick up the presence of metals, they have worked well on medieval manuscripts, whose ink contains iron. To dramatize what might be possible, Seales had made his own scroll, using a fresh sheet of papyrus on which he had written symbols with iron-gall ink, and which he then rolled up three times. He scanned it, and the result was an arresting simulation of images that depicted the scroll unrolling and the symbols showing clearly on the surface. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“But no one had ever done a 3-D scan on an ancient Herculaneum papyrus scroll before. “And I’m this naïve American,” Seales told me. “I think all I have to do is ask if I can scan one and they’ll say yes.” The National Library in Naples, where the vast majority of the scrolls are kept, eventually rejected his proposal. \=/

“After the talk, Delattre introduced himself to Seales, and explained that there were six scrolls in Paris. Seales had not known about them. “Mais oui,” Delattre said. And he, Daniel Delattre, was the primary scholar. \=/

“In the course of obtaining permission to scan the Paris scrolls, Seales had to give a presentation, in French, to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, an academy within the Institut de France. “I just wanted to run and hide before that talk, I was so nervous,” he said. His request was approved. In 2009, with a grant from the National Science Foundation, Seales had a portable CT scanner brought to the institute, and he spent four weeks scanning two unopened scrolls. \=/

“In the resulting images, the folds in the papyrus look cellular, almost biological. Here and there, grains of sand, perhaps trapped in the scrolls when a sandy bather had finished reading, are clearly visible. Seales proposed using these as orientation points for navigating within the labyrinthine volumes. \=/

“But the CT scans did not show any letters. There was lead in the ink, but only trace amounts. Though the ink did contain carbon, it did not stand out against the carbon in the blackened papyrus. Seales said, “We hoped that we could look for calcium or other trace compounds in the ink that might help us tease out the writing, but that didn’t work out.” \=/

X-ray Fluorescence Imaging of the Herculaneum Papyri

XPCT machine

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “In 2010, at a digital-restoration conference in Helsinki, Seales met Uwe Bergmann, a physicist at Stanford. Seales was familiar with Bergmann’s work on the Archimedes Palimpsest. In the early nineteen-hundreds, scholars had discovered that two lost works of Archimedes, the third-century- B.C. Greek mathematician and inventor, lay beneath a medieval religious text; a third work, which was also found, had survived in Latin translation. The palimpsest was probably made in Jerusalem, in the thirteenth century. Parchment was in short supply there, and a scribe had scraped away at a tenth-century copy and written over it. Using MSI, researchers could see the titles—“Stomachion,” “The Method of Mechanical Theorems,” and “On Floating Bodies”—but they couldn’t decipher all of the text beyond what was visible to the naked eye.* [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“When Bergmann read about the palimpsest, in an article in GEO that his mother had given him, he immediately thought of employing a synchrotron, a type of particle accelerator—a machine that uses magnets and microwaves to move subatomic particles at almost the speed of light. Some accelerators are linear, others are ring-shaped; Stanford has both kinds. In a synchrotron, the particles’ trajectory is altered to produce powerful X rays, which can be focussed into a beam about the width of a strand of hair. With this beam, it is possible to produce images of molecular structure; the synchrotron has become an immensely useful tool for the drug and electronics industries in developing and studying new compounds. \=/

“The beam can be “tuned” to look for particular elements. “The article said that the ink the scribes had used contained iron,” Bergmann said. “That’s one thing we do at the Stanford synchrotron. We measure iron and other metals in proteins—extremely small concentrations of iron.” \=/

“Once he obtained access to the palimpsest, Bergmann used X-ray fluorescence imaging, or XRF, in the synchrotron to get pictures of the iron-based molecules in the ink. Unlike MSI, XRF is sensitive to individual elements. Different elements emit characteristic wavelengths of light when the X rays hit them; by zeroing in on iron, Bergmann was able to see the letters. “What had been invisible for centuries was made, right before our eyes, visible,” he said, in an interview published by the Department of Energy. “Line by line, Archimedes’ original writings began to come to life, literally glowing on our screens. It was the most amazing thing.” \=/

“At the Helsinki conference, Seales pointed out to Bergmann that XRF wouldn’t work on the unopened scrolls, because it doesn’t penetrate deep enough; it would scan only the outer layers. “And Uwe didn’t bat an eye,” Seales told me. “He said, ‘Phase contrast, man.’ ” \=/

Phase Contrast (XPCT) of the Herculaneum Papyri

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “Phase contrast, or XPCT, is another microscopic-imaging tool made possible by synchrotrons. Because XPCT can penetrate surfaces much more deeply, it is used to measure density. A detector behind the sample being imaged captures the changing intensity of the beam as it passes through different atomic densities, which would allow the scroll researchers to map the indentations left by the stroke of the pen. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

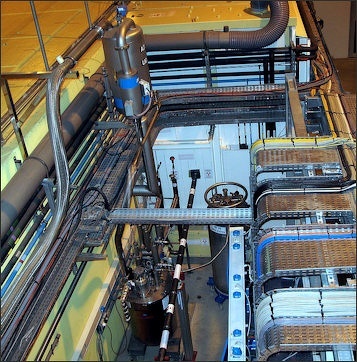

inside the ESRF synchrotron

“Bergmann and Seales were considering using Stanford’s synchrotron, but the Institut de France would not allow the scrolls to leave the country. There was a synchrotron just outside Paris, but “beam time” there cost about twenty-five thousand dollars a day, and Seales was unable to get a grant to pay for it. \=/

“By now, seeing inside an unopened scroll had become something of a quest for Seales. “We’ll read the scrolls,” he told me in an e-mail. “It’s been ten years and look at all we have achieved. From impossible to plausible, even probable. From the wreck of Herculaneum lore, we’ve created a body of systematic, scientific work.” It was only a question of getting the beam time. \=/

“The swerve in Seales’s plans was Vito Mocella, a physicist at the Institute for Microelectronics and Microsystems, in Naples, who also happened to be interested in the scrolls. In 2007, he was on a family holiday in Capri at the same time that a conference of Herculaneum papyrologists was being held at his hotel. He overheard one of them talking about the problems with reading the scrolls and, he told me, he thought of phase contrast, which he uses regularly in his work on new drug compounds. “I thought that would perhaps solve the problem,” he said. \=/

“Mocella is a native Neapolitan; he looks a bit like John Lennon might have if he’d had an Italian wife who kept him well fed. He remembers seeing the scrolls for the first time in the National Library when he was ten. “I thought it was strange that the Piaggio Machine was still the best method of opening the scrolls,” he told me. “That machine was two hundred years old!” \=/

“Mocella had no problem getting beam time in a synchrotron. An old friend from his graduate-school days, Claudio Ferrero, was the head of the Data Analysis Unit at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, in Grenoble. Ferrero thought that he could get the E.S.R.F. to donate some beam time if Mocella could get his hands on a scroll. Ferrero described the amazing results that paleontologists were getting with fossilized eggs—the X-rays showed the shape and the density of the embryos inside. He thought that phase contrast might be able to pick up the writing. Papyrus is nonabsorbent, so the ink is slightly raised on the surface. \=/

“Mocella inquired at the National Library in Naples about the possibility of putting a scroll inside the synchrotron at Grenoble, and was told that it was out of the question. On learning of the scrolls at the Institut de France, he contacted Delattre in the summer of 2013, and secured his help in getting the institute to agree to lend one scroll and fragments of one of the damaged ones. Late that fall, Delattre brought two fragments and a complete scroll, packed in a cylindrical foam case that Seales had designed for the CT scans, to Grenoble on the T.G.V. train from Paris. Seales, however, would not be travelling there with him. \=/

Using a Synchrotron to Read the Herculaneum Papyri

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “The E.S.R.F. is situated in an expansive research park, just above the confluence of two rivers, the Isère and the Drac, at the northern end of Grenoble, the small, mountain-ringed city that was the site of the 1968 Winter Olympics. The accelerator there is a ring, a kilometre in circumference. It is densely packed with “hutches,” where the experiments take place. Inside each hutch is an experiment room, where the beam collides with the sample, and a control room, where the scientists monitor the resulting scan on computers. The whole accelerator is enclosed in its own building, with grounds surrounding it and a guesthouse for visiting scientists. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“Delattre, as the conservator, was responsible for handling the fragments and the scroll, which had to be scanned individually. In the experiment room, he mounted each piece, one at a time, in a sample holder, where the beam would strike it. The two fragments were tilted; the scroll was placed vertically. Then he joined Mocella, Emmanuel Brun, a French physicist also with the E.S.R.F., and Ferrero in the control room and started the experiment. The sample was exposed to the beam. By turns, the beam passed through the two fragments and the scroll and its many layers, and struck the detector behind, which recorded the information about contrast densities. The beam is invisible, and exposure to it is dangerous; the researchers had to remain in the control room during the scans, which generally lasted for a few hours. The sample holder rapidly rotated the scroll and the fragments in microfractions of three hundred and sixty degrees as the beam flashed. Because the beam is so small, millions of exposures are needed to get a 3-D picture of a scroll. Although the letters are only two or three millimetres high, hundreds of scans are required to get enough information to make out a single letter. \=/

ESRF in Grenoble

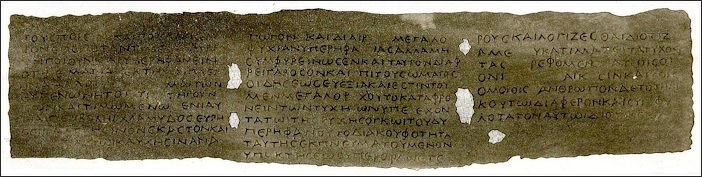

“The team waited nervously while the machines compiled the results. (Rendering the scans into images takes tremendous computer power.) On the second day, they began to see images. At first, the landscape looked bleak, barren of readable surfaces. The carbon in the crosshatched papyrus fibres (the sheets were made by pressing two pieces of papyrus together) stood out as dark streaks. But later that day the team had “an impression,” as Mocella puts it, of letters in one spot on the intact scroll, on an exposed edge about two-thirds of the way in. After two weeks of work, Delattre confirmed the impression. Altogether, the team found writing scattered throughout the scroll, and in one fragment they found a series of letters next to each other—pi, iota, pi, tau, omicron, iota—which means “would fall.” \=/

“The article in which the team reported their findings, “Revealing Letters in Rolled Herculaneum Papyri by X-Ray Phase-Contrast Imaging,” published in Nature Communications, in January, 2015, brought almost as much attention to the scrolls as had Paderni’s letter to Mead. As proof that the concept of virtual unwrapping could work, it was a milestone. “It’s the first hope of real progress we’ve had in a long time,” David Sider, of N.Y.U., told me. But, so far, the rate at which the team is reading the text makes Piaggio’s machine seem positively to hum by comparison. \=/

Political Obstacles Hinder Reading of the Herculaneum Papyri

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “Brent Seales, denied the scientific glory of being the first to see inside the rolled scrolls, has been focussing on the software side of the problem. If large portions of wrapped scrolls are ever going to be read virtually, the process will have to be automated. You’d need a scroll reader that skims along the surface of each successive fold, looking for characteristic shapes and densities of letters. Seales has been designing a prototype for such software, and he showed it to Delattre recently. “Impressive” was the Frenchman’s opinion. Janko thinks that “clearly the way forward from here is to combine the work Seales is doing with Mocella’s data.” [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“Such a convergence seemed poised to occur this spring, when Seales, Delattre, and Mocella were set to meet in Grenoble, for another synchrotron session: the software engineer, the papyrologist, the physicist, and a whole week of beam time. (Seales still wasn’t part of the team, but he was coming anyway, to present his virtual-unwrapping software.) At the last minute, though, the team didn’t get the scroll. Only days before the experiment was set to begin, the Institut de France indicated that it could not grant Mocella’s request. No official reason was offered, but the recent publicity about the virtual unwrapping was thought to have caused the institute to reëvaluate the scrolls in terms of intellectual property. Controlling access to the scrolls has always been a form of power. \=/

Herculaneum Papyri

“The institute’s decision was a blow to Delattre. When I saw him not long afterward, in the institute’s library, he still seemed shaken. While the box containing Objet Un was open, I asked Delattre whether he thought the scroll would ever be virtually unwrapped. He considered the question while gazing at the black, shrivelled lump of carbon. On the one hand, it was just an old burned-up word turd left behind by a minor Greek poet and unoriginal thinker. But, on the other hand, it was an invisible stream through which knowledge and pleasure and advancement flowed—if only you could get the access. “I do not expect this scroll will be read during my lifetime,” Delattre said, finally. He closed the lid of the small box with both hands, his shoulders slumped in defeat.” \=/

Herculaneum Papyri Finally Read with the Help of AI

In 2024, it was announced that AI (artificial intelligence) had deciphered part of an ‘unreadable’ Herculaneum scroll. Euronews reported: Using a groundbreaking, noninvasive technique, Italian researchers have deciphered over 1,000 words, or about one-third of the text, from one of the scrolls, according to an April 23 news release from the University of Pisa. The technique utilizes AI along with optical coherence tomography, an imaging technique, and infrared hyperspectral imaging technology to read sequences of previously hidden text from the papyri that had been partially destroyed. [Source: Jonny Walfisz, Euronews, April 30, 2024]

To encourage the deciphering of the Herculaneum Papyri, the Vesuvius Challenge was set up in 2023 with a prize fund of over $1 million (€930,000) for researchers who could make headway with the charred scrolls. Since then, 21-year-old Luke Farritor won $40,000 (€37,000) from the challenge for successfully decoding the first full word of the scrolls when he found the word “ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑ ” (purple). Earlier in 2024, year, Youssef Nader, Julian Schilliger and Farritor won a top prize of $850,000 (€790,000) for successfully decoding 5 percent of one of the scrolls of the papyri.

How the Herculaneum Papyri Were Read

In February 2024, the Silicon Valley investor-backed Vesuvius Challenge awarded $700,000, to a team of three competitors — Luke Farritor, an undergraduate at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; Youssef Nader, a doctoral student at Freie Universität Berlin; and Julian Schilliger, who recently earned his master’s degree in robotics from ETH Zürich. They worked together to reveal 15 columns of text totalling more than 2,000 characters from an intact scroll.

At the time the award was given,Sarah Kuta wrote in National Geographic: Papyrologists had produced a preliminary transcript of the newly revealed text, which represents about 5 percent of the scroll’s content. They’re still working to analyze the text, but shared a few snippets that amount to a “2,000-year-old blog post about how to enjoy life,” according to the contest organizers. [Source: Sarah Kuta, National Geographic, February 7, 2024]

The newly revealed passages build upon “πορφύραc,” a single word from the scroll, which two of the three winning competitors revealed independently in October, 2023. The colorful ancient Greek word refers to purple dye or purple-colored clothes — a color closely associated with royalty and power.

“We knew if we could read just one [scroll], then all the other ones would be available with the same method or some augmented method,” says Seales, the computer scientist at the University of Kentucky and head of the university’s Digital Restoration Initiative. “We are now proving not just to ourselves but to the entire global community that the scrolls are readable.”

Seales’ Digital Restoration Initiative team developed software that could “virtually unwrap” the 3D images to produce flattened segments. This method enabled them to read previously hidden text from the Ein Gedi scroll, a charred and fragmented scroll from the Middle East dated to the third or fourth century A.D. When researchers tried to use this method to read the scrolls carbonized by Vesuvius, however, they ran into another roadblock. The ink used on the Ein Gedi scroll contained metal, which meant the letters were visible on the CT scan. The Herculaneum scrolls, by contrast, were written with carbon-based ink, which, to the human eye, makes the symbols indistinguishable from the carbonized papyrus on the CT scans.

Undeterred, researchers wondered if higher-resolution scans of the scrolls produced by a particle accelerator could provide an even more detailed view of the carbonized papyrus. Sure enough, at very high resolutions, the scans revealed visible areas where the ink slightly altered the shape and texture of the papyrus fibers. “The carbon-based ink sort of fills in the holes that are the grid of the papyrus — it coats them and makes them a little thicker,” says Seales.

Seales and his Digital Restoration Initiative colleagues then developed and trained a machine learning model to detect these subtle differences in the carbonized papyrus surfaces. But to take the project any further, they needed human beings to help. That’s where the Vesuvius Challenge comes in. Hoping to harness the collective power of citizen scientists around the world, Seales teamed up with Silicon Valley investors and put his team’s data, code, and methods online for anyone to access.

What the Newly-Read Herculaneum Papyri Says

The “preliminary” translation of the Greek text provided by the Vesuvius Challenge reads: “As too in the case of food, we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant. Such questions will be considered frequently.”Later, the author wrote that their ideological adversaries “have nothing to say about pleasure, either in general or in particular, when it is a question of definition.” The scroll ends by saying “… for we do [not] refrain from questioning some things, but understanding/remembering others. And may it be evident to us to say true things, as they might have often appeared evident!” [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, February 8, 2024]

Sarah Kuta wrote in National Geographic: Based on what they’ve gleaned so far, papyrologists suspect the unnamed scribe was Philodemus, a follower of the Greek philosopher Epicurus, who valued pleasure above all else. One passage, for instance, contemplates how abundance or scarcity might affect sources of pleasure like music and food. “We do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant,” the author writes. [Source: Sarah Kuta, National Geographic, February 7, 2024]

Historians suspect Philodemus was the philosopher-in-residence at the Herculaneum villa where the charred scrolls were found — a villa likely owned by Julius Caesar’s father-in-law. The deciphered text mentions Xenophantos, for instance, who may be the same musician Philodemus notes in other writings. The author also criticized his adversaries — likely the Stoics — for having “nothing to say about pleasure, either in general or in particular, when it is a question of definition.”

Part of Plato’s narrative regarding his final moments before his death was read from Herculaneum Papyri by a team led by Professor Graziano Ranocchia from the University of Naples using a bionic eye. In a presentation at the National Library of Naples, Ranocchia thanked “the most advanced imaging diagnostic techniques”. “We are finally able to read and decipher new sections of texts that previously seemed inaccessible,” he said. [Source: Barbie Latza Nadeau, CNN, May 1, 2024]

See Scroll Charred by Vesuvius Eruption Reveals Plato’s Final Hours Under PLATO: HIS LIFE, ACADEMY, DEATH, INFLUENCES europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024