Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

STRONG FEMALE FIGURES IN ANCIENT GREECE

Hercules fighting an Amazon

María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: For many centuries, beliefs about the roles of girls and women in ancient Greece centered around how limited and hidden their lives were. Women were kept out of the public sphere, denied citizenship, and held no legal or political standing. Excluded from the polis, women were relegated to the oikos, or household, as wives, mothers, and daughters. [Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

Much of this notion originated in written sources from classical Greece. Xenophon, Plato, and Thucydides all testified to the so-called inferiority of women to men. Writing in the fourth century B.C., Aristotle stated, in his Politics, that “again, as between the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject.” Many of these texts originated in Athens, which had the most restrictive attitudes toward women. Other city-states, like Sparta, had greater freedoms for women, who were encouraged to exercise and train.

Penelope, wife of Odysseus, may not have existed at all but she still succeeded in leaving a legacy taught to new generations of Greeks for centuries by itinerant poet-storytellers. The virtues, values and roles ascribed to Penelope became, in effect, the standard to which women in that situation were expected to aspire. The story is well known. Odysseus, King of Ithaca and the man responsible for the idea of the Trojan horse tried to return home after the long war with Troy. But he had offended Poseidon and the ruler of the seas threw many obstacles in his path. Odysseus, a reluctant warrior, had left his household in charge of his wife. Now she was being besieged by suitors who thought her husband was dead and wanted his wife and valuable property. Penelope outsmarted them. The woman that Homer portrays is one who can stand on her own two feet, is a partner with her husband in the life of the family and a real role model. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Aspasia, daughter of Axiochus, was born in the city of Miletus in Asia Minor (present day Turkey) around 470 B.C. . She was highly educated and attractive. Athens, at that time, was in its golden age and as a city must have had the kind of appeal that New York, London and Paris have today. Aspasia moved there around 445 B.C. and was soon part of the local social circuit. Some of the most influential minds of the era spoke highly of her intelligence and debating skills. Socrates credited her with making Pericles a great orator and with improving the philosopher's own skills in rhetoric. She contributed to the public life of Athens and to the enlightened attitude of its most influential citizens.

José Noain wrote: Because she was not born in Athens, Aspasia was free from the conventions binding Athenian women. Renowned for her beauty and intelligence, she moved in the same circles as some of the most important men in fifth-century B.C. Athens, including Socrates and the sculptor Phidias. Some historians believe she ran a popular salon where Athens’s great thinkers would gather, but others characterize it as a brothel. None of Aspasia’s own writings have survived, erasing her voice from the record. It is an absence that leaves much to speculation about who she really was.

Hypatia, daughter of Theon of Alexandria, was born in that city around 350 AD. She studied and later taught at the great school in Alexandria. Some modern mathematicians acclaim her as having been “the world's greatest mathematician and the world's leading astronomer”, a viewpoint shared by ancient scholars and writers. She became head of the Platonist school at Alexandria lecturing on mathematics, astronomy and philosophy attracting students from all over the ancient world. Political and religious leaders in Alexandria sought her advice.

See Separate Articles: WOMEN IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT GREECE: WIVES, ROLES, KIDS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece”

by Joan Breton Connelly (2007) Amazon.com;

The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World”

by Adrienne Mayor (2016) Amazon.com;

“Searching for the Amazons: The Real Warrior Women of the Ancient World”

by John Man (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era”

by Jessica Amanda Salmonson (1992) Amazon.com;

“Olympias: Mother of Alexander the Great” by Elizabeth D. Carney (2006) Amazon.com;

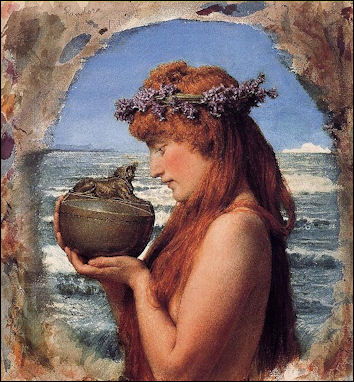

“Pandora's Jar: Women in the Greek Myths” by Natalie Haynes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Divine Might: Goddesses in Greek Myth” by Natalie Haynes (2023) Amazon.com;

“Women and Monarchy in Macedonia” by Carney (2021) Amazon.com;

“Spartan Women” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (2002) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece” by Susan Blundell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Bonnie MacLachlan (2012) Amazon.com;

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation” by Maureen B. Fant and Mary R. Lefkowitz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece” by Paul Chrystal (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Missing Thread: A Women's History of the Ancient World” by Daisy Dunn (2024) Amazon.com;

“Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore” by Jennifer Larson (2001) Amazon.com;

“Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion” by Matthew Dillon (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Sacred and the Feminine in Ancient Greece” by by Sue Blundell, Margaret Williamson, et al. | (1998) Amazon.com;

“Women in Hellenistic Egypt: From Alexander to Cleopatra”

by Sarah B. Pomeroy (1984) Amazon.com;

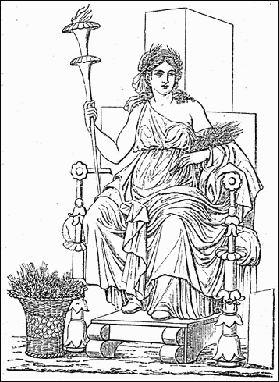

Ancient Greek Goddesses

Demeter On the four main Greek goddesses, art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “Like most gods in most cultures they are moody, contradictory personalities, above-it-all in knowledge but quick to play personal politics and intervene in human fate...Athena comes on as a striding warrior goddess, armed and dangerous, avid as a wasp, in a tiny bronze statuette from the fifth century B.C. This is the goddess who, in “The Iliad,” egged the Greeks on and manipulated their victory against Troy, and the one who later became the spiritual chief executive of the Athenian military economy.Yet seen painted in silhouette on a black vase, she conveys a different disposition. She’s still in armor but stands at ease, a stylus poised in one hand, a writing tablet open like a laptop in the other. The goddess of wisdom is checking her mail, and patiently answering each plea and complaint.” [Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, December 18, 2008]

Artemis is equally complex. A committed virgin, she took on the special assignment of protecting pregnant women and keeping an eye on children, whose carved portraits filled her shrines. She was a wild-game hunter, but one with a deep Franciscan streak. In one image she lets her hounds loose on deer; in another she cradles a fawn. But no sooner have we pegged her as the outdoorsy type than she changes. On a gold-hued vase from the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg she appears as Princess Diana, to use her Roman name, crowned and bejeweled in a pleated floor-length gown.

Demeter was worshiped as an earth goddess long before she became an Olympian. Her mystery cult had female priests, women-only rites and a direct line to the underworld. And although you might not expect Aphrodite, paragon of physical beauty, to have a dark side, she does. She was much adored; there were shrines to her everywhere. And she had the added advantage of being exotic: she seems to have drifted in from somewhere far east of Greece, bringing a swarm of nude winged urchins with her. But as goddess of love she was unreliable, sometimes perverse. Yes, she brings people amorously together, but when things go wrong, watch out: “Like a windstorm/Punishing the oak trees,/Love shakes my heart,” wrote the poet and worshiper of women, Sappho.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK GODDESSES AND MYTHOLOGICAL WOMEN europe.factsanddetails.com

Working Women in Ancient Greece

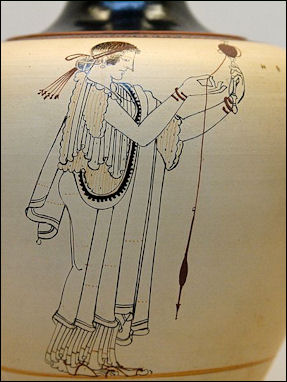

Woman spinning Lower class women often worked while middle class and upper class women devoted their attention primarily to domestic chores. Trades available to women included things like woolworking, clothes cleaning, breadmaking and nursing.

According to Xenophon, Socrates once asked a man named Ischomchus. "I should very much like you to tell me...whether you yourself trained your wife to become the sort of woman that ought to be or whether she already knew how to carry out her duties when you took her as your wife from her father and mother." Ischommachus replied, "What should she have known when I took her as my wife, Socrates? She was not yet 15 when she came to me, and had spent her previous years under careful supervision so that she might see and hear and speak a little as possible."

It is believed that women spent most of their time weaving. Wool was the most common fiber available and flax was also widely used. Cotton was stuffed into the saddles of Alexander the Great's cavalry in India to relieve soreness but that was largely the extent of its introduction to Greece.| [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: There were some women who received educations and made notable contributions in the arts and sciences. Around 350 B.C., Axiothea of Phlius studied philosophy under Plato (some sources say she disguised herself as a man to do so). In the sixth century B.C., the Delphic priestess Themistoclea (also known as Aristoclea) was a philosopher in her own right and a purported teacher of the famed philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras.[Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

Women in Sparta and Gortyn

Spartan women had more freedoms and rights than other Greek women. Plutarch wrote that Spartan marriage was matrilocal and that "women ruled over men." Spartan women were almost as tough as the men. They worked out by by running, wrestling and exercising so they could "undergo the pains of childbearing.” Girls were trained in athletics, dancing and music. They lived at home, while boys lived apart in their barracks. As adults, women participated in their own athletic events and performed naked like the men.

In Sparta, women competed in front of the men nude in "gymnastics," which at that times meant "exercises performed naked." The Spartan women also wrestled but there is no evidence that they ever boxed. Most events required the women to be virgins and when they got married, usually the age of 18, their athletic career was over. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: Sparta was not the only city where women enjoyed more freedoms than the women in Athens. According to its fifth-century B.C. Great Code, Gortyn, a city on the island of Crete, allowed women to inherit and manage property, recognizing the value of women’s work as a generator and protector of wealth. In addition to managing their own assets, women could control the possessions of their children if the children’s male guardian was unfit. Evidence of legislation governing marriage, divorce, and the possession of property among Gortyn’s enslaved population has been preserved, providing insight into how the lives of women differed depending on their social class. [Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

Aristotle on Spartan Women

Spartan woman

On Spartan Women, Aristotle (384-323 B.C.) wrote: “Again, the license of the Lacedaemonian women defeats the intention of the Spartan constitution, and is adverse to the happiness of the state. For, a husband and wife being each a part of every family, the state may be considered as about equally divided into men and women; and, therefore, in those states in which the condition of the women is bad, half the city may be regarded as having no laws. And this is what has actually happened at Sparta; the legislator wanted to make the whole state hardy and temperate, and he has carried out his intention in the case of the men, but he has neglected the women, who live in every sort of intemperance and luxury. The consequence is that in such a state wealth is too highly valued, especially if the citizen fall under the dominion of their wives, after the manner of most warlike races, except the Celts and a few others who openly approve of male loves. The old mythologer would seem to have been right in uniting Ares and Aphrodite, for all warlike races are prone to the love either of men or of women. This was exemplified among the Spartans in the days of their greatness; many things were managed by their women. But what difference does it make whether women rule, or the rulers are ruled by women? [Source: Aristotle, “The Politics of Aristotle,: Book 2", translated by Benjamin Jowett (London: Colonial Press, 1900)]

“The result is the same. Even in regard to courage, which is of no use in daily life, and is needed only in war, the influence of the Lacedaemonian women has been most mischievous. The evil showed itself in the Theban invasion, when, unlike the women other cities, they were utterly useless and caused more confusion than the enemy. This license of the Lacedaemonian (Spartan) women existed from the earliest times, and was only what might be expected. For, during the wars of the Lacedaemonians, first against the Argives, and afterwards against the Arcadians and Messenians, the men were long away from home, and, on the return of peace, they gave themselves into the legislator's hand, already prepared by the discipline of a soldier's life (in which there are many elements of virtue), to receive his enactments. But, when Lycurgus, as tradition says, wanted to bring the women under his laws, they resisted, and he gave up the attempt. These then are the causes of what then happened, and this defect in the constitution is clearly to be attributed to them. We are not, however, considering what is or is not to be excused, but what is right or wrong, and the disorder of the women, as I have already said, not only gives an air of indecorum to the constitution considered in itself, but tends in a measure to foster avarice.

“The mention of avarice naturally suggests a criticism on the inequality of property. While some of the Spartan citizen have quite small properties, others have very large ones; hence the land has passed into the hands of a few. And this is due also to faulty laws; for, although the legislator rightly holds up to shame the sale or purchase of an inheritance, he allows anybody who likes to give or bequeath it. Yet both practices lead to the same result. And nearly two-fifths of the whole country are held by women; this is owing to the number of heiresses and to the large dowries which are customary. It would surely have been better to have given no dowries at all, or, if any, but small or moderate ones. As the law now stands, a man may bestow his heiress on any one whom he pleases, and, if he die intestate, the privilege of giving her away descends to his heir. Hence, although the country is able to maintain 1500 cavalry and 30,000 hoplites, the whole number of Spartan citizens fell below 1000. The result proves the faulty nature of their laws respecting property; for the city sank under a single defeat; the want of men was their ruin.”

Powerful Priestesses in Ancient Greece

Priestess of Delphi

by Collier In a review of Joan Breton Connelly’s “Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece”, Steve Coates wrote in the New York Times, “In the summer of 423 B.C., Chrysis, the priestess of Hera at Argos, fell asleep inside the goddess’s great temple, and a torch she had left ablaze set fire to the sacred garlands there, burning the building to the ground. This spectacular case of custodial negligence drew the attention of the historian Thucydides, a man with scant interest in religion or women. But he had mentioned Chrysis once before: the official lists of Hera’s priestesses at Argos provided a way of dating historical events in the Greek world, and Thucydides formally marked the beginning of the Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece. [Source: Steve Coates, New York Times, July 1, 2007]

During the same upheaval, in 411, Thucydides’ fellow Athenian Aristophanes staged his comedy “Lysistrata,” with a heroine who tries to bring the war to an end by leading a sex strike. There is reason to believe that Lysistrata herself is drawn in part from a contemporary historical figure, Lysimache, the priestess of Athena Polias on the Acropolis. If so, she joins such pre-eminent Athenians as Pericles, Euripides and Socrates as an object of Aristophanes’ lampoons. On a much bigger stage in 480 B.C., before the battle of Salamis, one of Lysimache’s predecessors helped persuade the Athenians to take to their ships and evacuate the city ahead of the Persian invaders — a policy that very likely saved Greece — announcing that Athena’s sacred snake had failed to eat its honey cake, a sign that the goddess had already departed.

These are just some of the influential women visible through the cracks of conventional history in Joan Breton Connelly’s eye-opening “Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece.” Her portrait is not in fact that of an individual priestess, but of a formidable class of women scattered over the Greek world and across a thousand years of history, down to the day in A.D. 393 when the Christian emperor Theodosius banned the polytheistic cults. It is remarkable, in this age of gender studies, that this is the first comprehensive treatment of the subject, especially since, as Connelly persuasively argues, religious office was, exceptionally, an “arena in which Greek women assumed roles equal ... to those of men.” Roman society could make no such boast, nor can ours.

Despite powerful but ambiguous depictions in Greek tragedy, no single ancient source extensively documents priestesses, and Connelly, a professor at New York University, builds her canvas from material gleaned from scattered literary references, ancient artifacts and inscriptions, and representations in sculpture and vase painting. Her book shows generations of women enjoying all the influence, prestige, honor and respect that ancient priesthoods entailed. Few were as exalted as the Pythia, who sat entranced on a tripod at Delphi and revealed the oracular will of Apollo, in hexameter verse, to individuals and to states. But Connelly finds priestesses who were paid for cult services, awarded public portrait statues, given elaborate state funerals, consulted on political matters and acknowledged as sources of cultural wisdom and authority by open-minded men like the historian Herodotus. With separation of church and state an inconceivable notion in the world’s first democracy, all priesthoods, including those held by women, were essentially political offices, Connelly maintains. Nor did sacred service mean self-abnegation. “Virgin” priestesses like Rome’s Vestals were alien to the Greek conception. Few cults called for permanent sexual abstinence, and those that did tended to appoint women already beyond childbearing age; some of the most powerful priesthoods were held by married women with children, leading “normal” lives.

Athens’ roughly 170 festival days would have brought women out in public in great numbers and in conspicuous roles. “Ritual fueled the visibility of Greek women within this system,” Connelly writes, sending them across their cities to sanctuaries, shrines and cemeteries, so that the picture that emerges “is one of far-ranging mobility for women across the polis landscape.”

See Priestesses in Ancient Greece Under ANCIENT GREEK RELIGIOUS PRACTICES: PRIESTS, PRIESTESSES, RITUALS AND PRAYERS europe.factsanddetails.com; Also ORACLES IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; ORACLE IN DELPHI: PYTHIA, TEMPLE, VAPORS europe.factsanddetails.com

Book: “Portrait of a Priestess, Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece” by Joan Breton Connelly (Princeton University Press, 2007]

Herodotus on Artemisia at Salamis

Diana and Actaeon Artemesia was a woman ruler of Halicarnassus, who took part in the Persian attack on Athens.

On here, Herodotus wrote (480 B.C.): “Of the other lower officers I shall make no mention, since no necessity is laid on me; but I must speak of a certain leader named Artemisia, whose participation in the attack upon Hellas, notwithstanding that she was a woman, moves my special wonder. She had obtained the sovereign power after the death of her husband; and, though she had now a son grown up, yet her brave spirit and manly daring sent her forth to the war, when no need required her to adventure. Her name, as I said, was Artemisia, and she was the daughter of Lygdamis; by race she was on his side a Halicarnassian, though by her mother a Cretan. She ruled over the Halicarnassians, the men of Cos, of Nisyrus, and of Calydna; and the five triremes which she furnished to the Persians were, next to the Sidonian, the most famous ships in the fleet. She likewise gave to Xerxes sounder counsel than any of his other allies. Now the cities over which I have mentioned that she bore sway were one and all Dorian; for the Halicarnassians were colonists from Troizen, while the remainder were from Epidauros. Thus much concerning the sea-force. [Source: Herodotus, “Histories”, translated by George Rawlinson, New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

“Mardonius accordingly went round the entire assemblage, beginning with the Sidonian monarch, and asked this question; to which all gave the same answer, advising to engage the Hellenes, except only Artemisia, who spoke as follows: "Say to the king, Mardonius, that these are my words to him: I was not the least brave of those who fought at Euboia, nor were my achievements there among the meanest; it is my right, therefore, O my lord, to tell you plainly what I think to be most for your advantage now. This then is my advice: "Spare your ships, and do not risk a battle; for these people are as much superior to your people in seamanship, as men to women. What so great need is there for you to incur hazard at sea? Are you not master of Athens, for which you did undertake your expedition? Is not Hellas subject to you? Not a soul now resists your advance. They who once resisted, were handled even as they deserved. Now learn how I expect that affairs will go with your adversaries. If you are not over-hasty to engage with them by sea, but will keep your fleet near the land, then whether you stay as you are, or march forward towards the Peloponnesos, you will easily accomplish all for which you are come here. The Hellenes cannot hold out against you very long; you will soon part them asunder, and scatter them to their several homes. In the island where they lie, I hear they have no food in store; nor is it likely, if your land force begins its march towards the Peloponnesos, that they will remain quietly where they are — at least such as come from that region. Of a surety they will not greatly trouble themselves to give battle on behalf of the Athenians. On the other hand, if you are hasty to fight, I tremble lest the defeat of your sea force bring harm likewise to your land army. This, too, you should remember, O king; good masters are apt to have bad servants, and bad masters good ones. Now, as you are the best of men, your servants must needs be a sorry set. These Egyptians, Cyprians, Cilicians, and Pamphylians, who are counted in the number of your subject-allies, of how little service are they to you!"

Alma-Tadema's pandora “As Artemisia spoke, they who wished her well were greatly troubled concerning her words, thinking that she would suffer some hurt at the king's hands, because she exhorted him not to risk a battle; they, on the other hand, who disliked and envied her, favored as she was by the king above all the rest of the allies, rejoiced at her declaration, expecting that her life would be the forfeit. But Xerxes, when the words of the several speakers were reported to him, was pleased beyond all others with the reply of Artemisia; and whereas, even before this, he had always esteemed her much, he now praised her more than ever. Nevertheless, he gave orders that the advice of the greater number should be followed; for he thought that at Euboia the fleet had not done its best, because he himself was not there to see — whereas this time he resolved that he would be an eye-witness of the combat.

“What part the several nations, whether Hellene or barbarian, took in the combat, I am not able to say for certain; Artemisia, however, I know, distinguished herself in such a way as raised her even higher than she stood before in the esteem of the king. For after confusion had spread throughout the whole of the king's fleet, and her ship was closely pursued by an Athenian trireme, she, having no way to fly, since in front of her were a number of friendly vessels, and she was nearest of all the Persians to the enemy, resolved on a measure which in fact proved her safety. Pressed by the Athenian pursuer, she bore straight against one of the ships of her own party, a Calyndian, which had Damasiyourmus, the Calyndian king, himself on board. I cannot say whether she had had any quarrel with the man while the fleet was at the Hellespont, or no — neither can I decide whether she of set purpose attacked his vessel, or whether it merely chanced that the Calyndian ship came in her way — but certain it is that she bore down upon his vessel and sank it, and that thereby she had the good fortune to procure herself a double advantage. For the commander of the Athenian trireme, when he saw her bear down on one of the enemy's fleet, thought immediately that her vessel was a Hellene, or else had deserted from the Persians, and was now fighting on the Hellene side; he therefore gave up the chase, and turned away to attack others.

“ Thus in the first place she saved her life by the action, and was enabled to get clear off from the battle; while further, it fell out that in the very act of doing the king an injury she raised herself to a greater height than ever in his esteem. For as Xerxes beheld the fight, he remarked (it is said) the destruction of the vessel, whereupon the bystanders observed to him — "See, master, how well Artemisia fights, and how she has just sunk a ship of the enemy?" Then Xerxes asked if it were really Artemisia's doing; and they answered, "Certainly; for they knew her ensign" — while all made sure that the sunken vessel belonged to the opposite side. Everything, it is said, conspired to prosper the queen — it was especially fortunate for her that not one of those on board the Calyndian ship survived to become her accuser. Xerxes, they say, in reply to the remarks made to him, observed: "My men have behaved like women, my women like men!"

Amazons

The Amazons were a band of fearless warriors described as "maidens fearless in battle" and "women the peers of men." They were lead by a queen who wore a belt to symbolize her power and lived on the north side of Black Sea. No men were allowed to live in their kingdom. The Amazons consorted with men only once a year during a festival. Afterwards the men that were used were turned into eunuchs, enslaved or killed. Only female offspring were kept, boys were disposed of.

The Amazons fought with spears, shields, bows and arrows. They supposedly cut off one of their breasts so they could carry a shield. The word Amazon is sometimes erroneously said to have been derived from the Greek for "without one breast." It more likely means "those who are not breast-fed."

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science, “Although details about them vary, the Amazons were depicted as beautiful and bloodthirsty women, with strong matriarchal ties. They heralded from what is now modern day Turkey. When called upon, the men played their part in reproduction, or they served as slaves. Male babies were often killed or sent back to their fathers, and girls were raised by their mothers to tend to crops, hunt and become the warriors they were famed for being.” [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 12, 2015]

See Separate Article: AMAZONS AND ANCIENT WARRIOR WOMEN europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024