Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

ANCIENT GREEK WOMEN

In ancient Greece, women had very few rights; they were not citizens and often were not allowed to leave the house. Inside their houses, they were relegated to rooms in the back of the house near the slave quarters. One classics professor told National Geographic: "The Greek polis was something of a men's club. Women tended to stay at home and do the household chores. They went out chiefly for ceremonies, festivals, and such duties as drawing waters. In myth, trysts often took place at wells. Going there was one way a woman got out of the house."

María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: Life for most women of means centered generally around three stages: kore (young maiden), nymphe (a bride until the birth of her first child), and gyne (woman). Adult life typically began in the early to mid-teens, when she would marry and formally move from her father’s household to her husband’s. Most brides had a dowry that her husband did not have access to, but if the marriage failed, the money would revert to her father. [Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

Some have argued that in ancient Greece, women were generally regarded as irrational, sex-obsessed and prone to hysteria. The word "hysteria" comes from Greek word for "uterus." The condition was regarded as a sort of "womb furie" that produced the symptoms such as confusion, laziness, depression, headaches, forgetfulness, stomach upsets, ticklishness, cramps, insomnia, weepiness, palpitations of the heart, and muscle spasms. Hysteria and women had been linked together since 2000 B.C., when healers observed that woman did nor release fluids like men during sexual intercourse and reasoned that fluids accumulate in the uterus where they caused a variety of problems and irrational behavior. Plato believed than in serious cases their uterus could fill with so much fluid it would become death and strangle its owner. These views persisted into the Victorian era.

It is a misconception that women had a universally passive role in Athenian society. Art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, It is true that they lived with restrictions modern Westerners would find intolerable. Technically they were not citizens. In terms of civil rights, their status differed little from that of slaves. Marriages were arranged; girls were expected to have children in their midteens. Yet... the assumption that women lived in a state of purdah, completely removed from public life, is contradicted by the depictions of them in art.” Yet, “it would be a mistake to argue that the lot of women there was, after all, a fair deal. The record stands: no citizenship, no vote, little or no control over the use made of your time or your body. But the show is not making that argument. Instead it is using art to survey where, within a system of institutionalized restriction, areas of freedom for women lay.

See Separate Articles: FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT GREECE: WIVES, ROLES, KIDS europe.factsanddetails.com ; STRONG WOMEN IN ANCIENT GREECE: GODDESSES, LEADERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Week in the Life of a Greco-Roman Woman” by Holly Beers Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece” by Susan Blundell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece”

by Joan Breton Connelly (2007) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Bonnie MacLachlan (2012) Amazon.com;

“Pandora's Daughters: The Role and Status of Women in Greek and Roman Antiquity”

by Eva Cantarella, Maureen B Fant, et al. (1987) Amazon.com;

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation” by Maureen B. Fant and Mary R. Lefkowitz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece” by Paul Chrystal (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Missing Thread: A Women's History of the Ancient World” by Daisy Dunn (2024) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece and Rome” (Cambridge Educational) by Michael Massey (1988) Amazon.com;

“Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World” by Christopher A. Faraone and Laura K. McClure (2006) Amazon.com;

“Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore” by Jennifer Larson (2001) Amazon.com;

“Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion” by Matthew Dillon (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Sacred and the Feminine in Ancient Greece” by by Sue Blundell, Margaret Williamson, et al. | (1998) Amazon.com;

“Women in Hellenistic Egypt: From Alexander to Cleopatra”

by Sarah B. Pomeroy (1984) Amazon.com;

“Women and Monarchy in Macedonia” by Carney (2021) Amazon.com;

“Spartan Women” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (2002) Amazon.com;

“Love Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Sofia A Souli (2018) Amazon.com;

“Love in Ancient Greece” by Robert Flacelière (1962) Amazon.com;

“Marriage to Death: The Conflation of Wedding and Funeral Rituals in Greek Tragedy” (Princeton Legacy Library) by Rush Rehm (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Family in Greek History” by Cynthia B. Patterson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Family” by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1830-1889) Amazon.com;

“Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past”

by Jenifer Neils , John H. Oakley , et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Different Views on Women in Ancient Greece

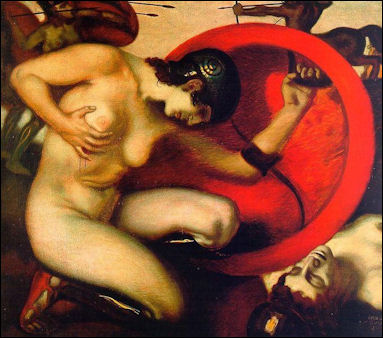

Wounded Amazon Pindar wrote in “The Hierodulai of Corinth” (c. 500 B.C.):

“O hospitable damsels, fairest train

Of soft Persuasion —

Ornament of the wealthy Corinth,

Bearing in willing hands the golden drops

That from the frankincense distil, and flying

To the fair mother of the Loves,

Who dwells in the sky,

The lovely Aphrodite — you do bring to us

Comfort and hope in danger, that we may

Hereafter, in the delicate beds of Love,

Reap the long-wished-for fruits of joy

Lovely and necessary to all mortal men.”

Some argue that the view of women in ancient Greece as being demure and housebound is not correct. There were some places where women were held in higher respect. "There was a strong tradition of matriarchy in Lokroi," one scholar told National Geographic. "The aristocrats, for instance, descended from the mother's side. Also, the cults of two Goddesses, Persephone and Aphrodite, were powerful here."

In Aristophanes’s “ Lysieria” the heroine laments: "What sensible thing are we women capable of doing? We do nothing but sit around with our paint and lipstick and transparent gowns and all the rest of it." To get even with the dominate male class she leads the women of Athens in a sex strike in which wives refuse to sleep with their husbands. The strike paralyzes the city and the women seize the Acropolis and the treasure of the Parthenon. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Wives in Ancient Greece

The Athenian regarded his wife as a subordinate being, who would bear him children and keep his house in order, but was incapable of rising beyond this sphere. A woman must keep silence about all political matters, and, as a rule, she was not even acquainted with her husband’s private affairs.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The life of Athenian women was entirely devoted to domestic affairs. The part of the house set aside for the wife and children, and afterwards for the grown-up daughters and the female slaves, was generally separate from the rest of the dwelling; and a Greek writer says that, as the door which separates the women’s apartments from the rest of the house is the boundary set for a maiden, so the door which shuts the house off from the street must be the boundary for the wife. We must not, however, suppose that Greek women were entirely shut off from publicity. The wives of poorer citizens, whose circumstances were, of course, quite different from those of the upper classes, went out of doors often enough. Some were compelled to do so by their occupation, and others, who had few or no slaves at their disposal, were obliged to go out every day to purchase food and other necessaries of life. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

It was very common for women to fetch water from the public wells, and to have a little chat there; but in rich houses this duty of fetching the water naturally fell to the slaves. We find allusions to these expeditions to the well in legends and in real life; and they are often represented on monuments, especially vase paintings. One vase gives an example of the kind taken from a vase painting in the antique style. On the left we see the well, surmounted by a Doric portico; the water is flowing from a lion’s mouth into a jug placed beneath it; the woman who has come to fill her vessel stands waiting beside it. On the right we see other women conversing in pairs; two have already filled their jars, and are carrying them on their heads, supported by a little cushion, according to the pretty custom which still prevails widely in the south; the vessels of the two others have not yet been filled, as we can tell from their position.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE: WIVES, ROLES, DIVORCE europe.factsanddetails.com

Low Status of Women in Ancient Greece

woman flute player at a symposium

In comparison with other civilizations in the ancient world, Greek women in general did not enjoy high status, rank and privilege. Even so enlightened a man as Pericles suggested in a major public speech that the more inconspicuous women were, the better it was for everyone. Sparta, which history clearly ranks as the cultural inferior of Athens on almost every scale, seems to have had a superior record in its treatment of women. And it wasn't outstanding. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

At social gatherings, intellectuals argued that perhaps men and women were two separate species. Men had more in common with the gods, while women had far more in common with the animal kingdom. (Perhaps this was an earlier, and fundamentally flawed, version of Men are from Mars: Women are from Venus). In any event, despite the efforts of many to ensure that women stayed in their proper place in the home and out of sight, a few did succeed in escaping that orbit. None flew as high as women in Egyptian society where several attained the highest office in the land- that of Pharaoh- but some Greek women managed to leave a public legacy. Following are three of them. |

Aristotle said: “The male is by nature superior and the female inferior…the one rules and the other is ruled.” An anonymous Greek said around 400 B.C.: “Good Women must abide within the house; Those whom we meet abroad are nothing worth. Hipponax wrote in c. 580 B.C.: “Two happy days a woman brings a man: the first, when he marries her; the second, when he bears her to the grave.” [Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

Discrimination Against Women in in Ancient Greece

Women were denied basic rights and expected to stay in their homes. Women were not normally allowed to testify in Athenian courts. They were usually "educated" in their husband's households.

Men sequestered their wives and daughters. The pale complexion a woman received from staying indoors all the time was seen as a sign of virtue and beauty. On the few occasions they were allowed to go out during daylight they were only allowed to bring a swallow of water and light snack and were required to be accompanied by a chaperon.

The veiling of women was common practice among women in ancient Greece, Rome and Byzantium. The Muslim custom of veiling and segregating women is believed to have its origins in customs that were common place in ancient Greece.

Women who engaged in premarital and extramarital sex were regarded as immoral although the same behavior was acceptable among men. Infant daughters were often abandoned and girls of 14 were routinely married to men twice their age or forced into prostitution.

Art, Religion and Women in Ancient Greece

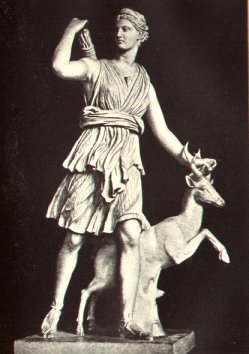

Goddess Artemis (Diana) A 2006 exhibition entitled “Worshiping Women: Ritual and Reality in Classical Athens” was put at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore by Nikolaos Kaltsas, director of the National Archaeological Museum of Greece, and Alan Shapiro, professor of archaeology at Johns Hopkins University . On the show Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “Much of that art is religious, which is no surprise considering the commanding female deities in the Greek pantheon.

Actual worship took various forms. Some were simple gestures. In several vase paintings we see women pouring wine, milk or honey from flat bowls onto the ground as an offering. In others they lead sacrificial animals to altars, a reminder that the white marble temples we now so admire for their purity were once splashed with blood.” [Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, December 18, 2008]

One vase fragment, showing a group of women looking jumpy and frazzled, was long assumed to depict an orgiastic festival in honor of Aphrodite’s boy-toy lover, Adonis, the James Dean of Greek myth, who died young and left a beautiful corpse and mobs of inconsolable female fans. Recently, though, scholars have concluded that this is a marriage scene, with an anxious bride being prepared by hovering attendants for her wedding night.

The management of weddings was female turf, as was childbirth and the raising of children. So were the rituals surrounding death. Men were in charge of war and killing; women were in charge of washing and dressing bodies for the all-important last rites, without which souls were left to wander the Earth. Birth and death — the only real democratic experiences, existentially speaking — were in women’s hands.

There is no more moving image in the show than that of two women, one seated and one standing, facing each other in carved relief on a marble grave stele dated to the fourth century B.C. Both may be priests, or worshipers, in an earth-goddess cult; neither looks young. An inscription identifies the woman commemorated by the stele as Nikomache. The exhibition catalog suggests that she is the seated figure, the one who has settled in and will keep her place when the other walks away. The parting is evidently in progress as the women clasp hands and meet each other’s gaze.

Sappho wrote in poem called “Long Departure”: Then I said to the elegant ladies: / “How you will remember when you are old / The glorious things we did in our youth! / We did many pure and beautiful things. / And now that you are leaving the city, / Love’s sharp pain encircles my heart.”

Women in Ancient Greek Drama

The playwright Aristophanes said in the Thesmophoriazusae that the men could place no trust whatever in their wives, and were obliged to keep them under lock and key, and keep Molossian hounds on purpose to frighten away their lovers, while they deprived them even of the keys of the storeroom. Athenian women were regarded as morally inferior to Spartan women and women from Corinth and Byzantium were ranked even lower morally than Athenian women.

In “Chorus of The Women” (c. 420 B.C.), Aristophanes wrote i: “Come now, if we are an evil, why do you marry us, if indeed we are really an evil, and forbid any of us either to go out, or to be caught peeping out, but wish to guard the evil thing with so great diligence? And if the wife should go out anywhere, and you then discover her to be out of doors, you rage with madness, who ought to offer libations and rejoice, if indeed you really find the evil thing to be gone away from the house and do not find it at home. And if we sleep in other peoples' houses, when we play and when we are tired, everyone searches for this evil thing, going round about the beds. And if we peep out of a window, everyone seeks to get a sight of the evil thing. And if we retire again, being ashamed, so much the more does everyone desire to see the evil thing peep out again. So manifestly are we much better than you. [Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260]

Antiphanes wrote in “Women” (c. 300 B.C.): “What! when you court concealment, will you tell the matter to a woman? Just as well tell all the criers in the public squares! 'Tis hard to say which of them louder blares. Great Zeus, may I perish, if I ever spoke against woman, the most precious of all acquisitions. For if Medea was an objectionable person, surely Penelope was an excellent creature. Does anyone abuse Clytemnestra? I oppose the admirable Alkestis. But perhaps someone may abuse Phaidra; then I say, by Zeus! what a capital person was . . . Oh, dear! the catalogue of good women is already exhausted.”

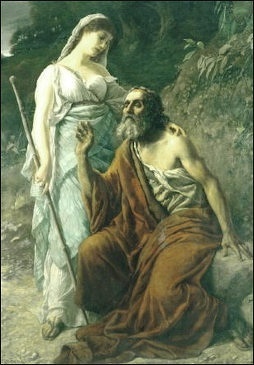

Antigone and Oedipus

“Menander wrote:

“Manner, not money, makes a woman's charm.

When you fair woman see, marvel not; great beauty's oft to countless faults allied.

Where women are, there every ill is found.

Marriage, if truth be told (of this be sure), An evil is — but one we must endure.

A good woman is the rudder of her household.

A sympathetic wife is man's chiefest treasure.

How burdensome a wife extravagant;

Not as he would may he who's ta'en her live.

Yet this of good she has: she bears him children;

She watches o'er his couch, if he be sick,

With tender care; she's ever by his side

When fortune frowns; and should he chance to die,

The last sad rites with honor due she pays.

Euripides wrote in “The Condition”:

“Of all things that are living and can form a judgment

We women are the most unfortunate creatures.

Firstly, with an excess of wealth it is required

For us to buy a husband and take one for our bodies

A master; for not to take one is even worse.

And now the question is serious whether we take

A good one or bad one; for there is no easy escape

For a woman, nor can she say not to her marriage.

She arrives among new modes of behaviour and manners,

And needs prophetic power, unless she has learned at home,

How best to manage him who shares the bed with her.

And if we work this out well and carefully,

And the husband lives with us and lightly bears his yoke,

Then life is enviable. If not, I'd rather die.

A man, when he's tired of the company in his home,

Goes out of the house and puts an end to his boredom

And turns to a friend or companion of his own age.

But we are forced to keep our eyes on one alone.

What they say of us is that we have a peaceful time

Living at home, while they do the fighting in war.

How wrong they are. I would very much rather stand

Three times in the front of battle than bear one child.

Hesiod Theogony on Women

Hesiod was a near contemporary of Homer and source of some of earliest descriptions of Zeus and the ancient Greek gods and creation story. In Theogony, (c. 700 B.C.), he wrote:

“Pernicious is the race; the woman tribe

“Dwells upon earth, a mighty bane to men;

No mates for wasting want but luxury;

And as within the close-roofed hive, the drones,

Helpers of sloth, are pampered by the bees;

These all the day, till sinks the ruddy sun,

Haste on the wing, 'their murmuring labors ply,'

And still cement the white and waxen comb;

Those lurk within the covered hive, and reap

With glutted maw the fruits of others' toil;

Such evil did the Thunderer send to man

Hesiod and a muse

In woman's form, and so he gave the sex,

Ill helpmates of intolerable toils.

Yet more of ill instead of good he gave:

The man who shunning wedlock thinks to shun

The vexing cares that haunt the woman-state,

And lonely waxes old, shall feel the want

Of one to foster his declining years;

Though not his life be needy, yet his death

Shall scatter his possessions to strange heirs,

And aliens from his blood. Or if his lot

Be marriage and his spouse of modest fame

Congenial to his heart, e'en then shall ill

Forever struggle with the partial good,

And cling to his condition. But the man

Who gains the woman of injurious kind

Lives bearing in his secret soul and heart

Inevitable sorrow: ills so deep

As all the balms of medicine cannot cure.

[Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Take to your house a woman for your bride

When in the ripeness of your manhood's pride;

Thrice ten your sum of years, the nuptial prime;

Nor fall far short nor far exceed the time.

Four years the ripening virgin shall consume,

And wed the fifth of her expanding bloom.

A virgin choose: and mould her manners chaste;

Chief be some neighboring maid by you embraced;

Look circumspect and long; lest you be found

The merry mock of all the dwellers round.

No better lot has Providence assigned

Than a fair woman with a virtuous mind;

Nor can a worse befall than when your fate

Allots a worthless, feast-contriving mate.

She with no torch of mere material flame

Shall burn to tinder your care-wasted frame;

Shall send a fire your vigorous bones within

And age unripe in bloom of years begin.’

Types of Women in Ancient Greece

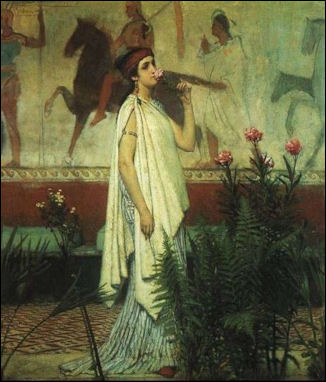

Upper class woman and her female servant

The status of women in ancient Greek was affected by differences between places and social classes. María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: Poor and enslaved women worked as laundresses, weavers, vendors, wet nurses, and midwives. Decorated ceramics showed scenes of enslaved women at market and collecting water. Scholars find more complexity in the realm of religion. The Greek pantheon is full of powerful female deities, such as Athena, goddess of war and wisdom and patron of Athens; or Artemis, goddess of the hunt and wilderness. Archaeologists are finding that the lives of priestesses allowed women more freedom and respect than previously thought. Rather than a monolithic experience, the roles of women in ancient Greece were varied. [Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

Phokylides of Miletus wrote in Satire on Women (c. 440 B.C.): “The tribe of women is of these four kinds — that of a dog, that of a bee, that of a burly sow, and that of a long-maned mare. This last is manageable, quick, fond of gadding about, fine of figure; the sow kind is neither good nor bad; that of the dog is difficult and snarling; but the bee-like woman is a good housekeeper, and knows how to work. This desirable marriage, pray to obtain, dear friend.” [Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

On Types of Women, Semonides of Amorgos wrote (c. 550 B.C.): “God made the mind of woman in the beginning of different qualities; for one he fashioned like a bristly hog, in whose house everything tumbles about in disorder, bespattered with mud, and rolls upon the ground; she, dirty, with unwashed clothes, sits and grows fat on a dungheap.The woman like mud is ignorant of everything, both good and bad; her only accomplishment is eating: cold though the winters be, she is too stupid to draw near the fire. The woman made like the sea has two minds; when she laughs and is glad, the stranger seeing her at home will give her praise — there is nothing better than this on the earth, no, nor fairer; but another day she is unbearable, not to be looked at or approached, for she is raging mad. To friend and foe she is alike implacable and odious. Thus, as the sea is often calm and innocent, a great delight to sailors in summertime, and oftentimes again is frantic, tearing along with roaring billows, so is this woman in her temper.

“The woman who resembles a mare is delicate and long-haired, unfit for drudgery or toil; she would not touch the mill, or lift the sieve, or clean the house out! She bathes twice or thrice a day, and anoints herself with myrrh; then she wears her hair combed out long and wavy, dressed with flowers. It follows that this woman is a rare sight to one's guests; but to her husband she is a curse, unless he be a tyrant who prides himself on such expensive luxuries. The ape-like wife has Zeus given as the greatest evil to men. Her face is most hateful. Such a woman goes through the city a laughing-stock to all the men. Short of neck, with narrow hips, withered of limb, she moves about with difficulty. O! wretched man, who weds such a woman! She knows every cunning art, just like an ape, nor is ridicule a concern to her. To no one would she do a kindness, but every day she schemes to this end — how she may work someone the greatest injury.

“The man who gets the woman like a bee is lucky; to her alone belongs no censure; one's household goods thrive and increase under her management; loving, with a loving spouse, she grows old, the mother of a fair and famous race. She is preeminent among all women, and a heavenly grace attends her. She cares not to sit among the women when they indulge in lascivious chatter. Such wives are the best and wisest mates Zeus grants to men. Zeus made this supreme evil — woman: even though she seem to be a blessing, when a man has wedded one she becomes a plague.”

Courtesans and Prostitutes in Ancient Greece

Greek aristocrats had courtesans and all-make drinking parties often featured naked prostitutes. Marriages who often arranged and men sought satisfaction with courtesans or male lovers. Prostitutes at Ephesus advertised their services outside the doorway of the brothel with an inscription of a foot and a woman with a mohawk haircut.◂

The Greek women with the most power and freedom, surprisingly, were courtesans, known as “ hetaeras” . When they weren't working Grecian courtesans didn't have to maintain an image of virtue so they could do what they wanted, and they had money to do it with. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

“On Wives and Hetairai (Prostitues),” “Demosthenes wrote (c. 350 B.C.): “We take a hetaira for our pleasure, a concubine for daily attention to our physical wants, a wife to give us legitimate children and a respected house.”

Grecian consorts were similar to geisha girls. They entertained their patrons with poems, dancing and singing at drinking parties (called “symposiums” ). Sex was extra, in some cases a lot extra. Sometimes their prices were set according to how many sexual positions they had mastered. One courtesan who had mastered 12 positions charged the most for one called “ keles” (meaning "racehorse" in which the woman mounted the man from the top).

See PROSTITUTES AND COURTESANS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

How Perceptions of Women in Ancient Greece Have Been Shaped

Lawrence Alma-Tadema's

vision of a Greek woman Coats wrote that Connelly’s well-documented, meticulously assembled portrait of women largely contradicts what has long been the most broadly accepted vision of the women of ancient Greece, particularly Athens, as dependent, cloistered, invisible and mute, relegated almost exclusively to housekeeping and child rearing — a view that at its most extreme maintains that the names of respectable Athenian women were not spoken aloud in public or that women were essentially housebound. Connelly traces the tenacity of this idea to several sources, including the paradoxically convergent ideologies of Victorian gentlemen scholars and 20th-century feminists and a modern tendency to discount the real-world force of religion, a notion now under powerful empirical adjustment. [Source: Steve Coates, New York Times, July 1, 2007]

But another cause is a professional divide between classicists and archaeologists. In their consideration of a woman’s place, classicists emphasize certain well-known texts, the most notorious being Thucydides’ rendition of Pericles’ great oration over the first Athenian dead of the Peloponnesian War, which had this terse advice for their widows: “If I must say anything on the subject of female excellence, ... greatest will be her glory who is least talked of among men, whether in praise or in criticism.” Connelly, though, is an archaeologist, and she insists that her evidence be allowed to speak for itself, something it does with forceful eloquence. Far from the names of respectable women being suppressed, it seems clear that great effort was made to ensure that the names of many of these women would never be forgotten: Connelly can cite more than 150 historical Greek priestesses by name. Archaeology also speaks through beauty: “Portrait of a Priestess” is an excellent thematic case study in vase painting and sculpture, with striking images of spirited women, at altars or leading men in procession, many marked as priestesses by the great metal temple key they carry, signifying not admission to heaven but the pragmatic responsibility that Chrysis so notoriously betrayed in Argos.

Among her more provocative points is debunking the idea that polytheism’s presumed spiritual failures may eventually have led to the Christian ascendancy. Connelly shows that the system long sustained and nourished Greek women and their communities. In turn, women habituated to religious privilege and influence in the pre-Christian era eagerly lent their expertise and energy to the early church. But with one male god in sole reign in heaven, women’s direct connection with deity became suspect, and they were methodically edged out of formal religious power. “There may be no finer tribute to the potency of the Greek priestess than the discomfort that her position caused the church fathers,” Connelly writes in her understated way. Her priestesses may be ancient history, but the consequences of the discomfort they caused endure to this day.

Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) On Rape and Adultery

The Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) is the most complete surviving Greek Law code. According to the Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: “In Greek tradition, Crete was an early home of law. In the 19th Century, a law code from Gortyn on Crete was discovered, dealing fully with family relations and inheritance; less fully with tools, slightly with property outside of the household relations; slightly too, with contracts; but it contains no criminal law or procedure. This (still visible) inscription is the largest document of Greek law in existence (see above for its chance survival), but from other fragments we may infer that this inscription formed but a small fraction of a great code.” [Source:Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“II. If one commit rape on a free man or woman, he shall pay 100 staters, and if on the son or daughter of an apetairos ten, and if a slave on a free man or woman, he shall pay double, and if a free man on a male or female serf five drachmas, and if a serf on a male or female serf, five staters. If one debauch a female house-slave by force he shall pay two staters, but if one already debauched, in the daytime, an obol, but if at night, two obols. If one tries to seduce a free woman, he shall pay ten staters, if a witness testify. . .

“III. If one be taken in adultery with a free woman in her father=s, brother=s, or husband=s house, he shall pay 100 staters, but if in another=s house, fifty; and with the wife of an apetairos, ten. But if a slave with a free woman, he shall pay double, but if a slave with a slave=s wife, five.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024