ANCIENT GREEK RELIGIOUS PRACTICES

sacrifice Greek religion was unacquainted with regular worship returning on certain appointed days, for which priests and laymen assembled together in the House of God. It is true the temple was regarded as the dwelling of the god; but the believer, as a rule, only entered it if he had some special prayer to make, and otherwise performed his religious duties at home in his own dwelling. This he could generally do without the help of a priest. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Religious tenets were not defined, and no priestly hierarchy attempted to coerce the people in their beliefs or actions. A Greek was not under the necessity of worshipping the gods, though he might incur the anger of his fellow-citizens by outraging their feelings. The head of every family was its priest, and the children his assistants in carrying out the worship of the divine beings who guarded the house and fields and all the living creatures therein. Similarly the great gods of the city were served by the priests and priestesses appointed to represent the city, conceived of as one great family. Each city had its recurring festivals, its rest days sacredly kept, and its days of commemoration of the dead. Public worship in Greece consisted of prayers and hymns, and of sacrifices offered both within the temples and shrines and in other places, such as groves and springs, which were held to be sacred. The temples were built and adorned with all possible care, and were the pride of the community. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

In prayer the worshipper looked upward and raised both hands. This position is represented in a bronze statuette, probably a votive offering. A small wine-jug is decorated with a similar scene before a statue of Athena raised on a low column stands, with a man saluting the goddess by kissing his fingers and raising them toward her. A bronze votive statuette has the same gesture. Food and drink were the simplest and commonest gifts to the gods, but were often beyond the means of the worshipper. Miniature bronze greaves have been fund at temples. They were probably dedications, perhaps made by soldiers after a battle. Little masks called “oscilla” which were hung by cords in sanctuaries or on the branches of trees outside. They seem to have been a substitute for the worshipper when he was obliged to be away about his daily occupation. A group of terracotta figures holding one another’s hands gives a picture of a ring-dance such as was performed in honor of Aphrodite in Cyprus. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

No meal was eaten without offering a portion of food and drink to the gods, and statuettes and symbols of divinities were kept in various rooms of the house and near the house-door. The rude bust of Hermes on a pillar is of the same type as the much larger pillars which in Athens were placed near house-doors, in schools, and in the market-place. It was the mutilation of these images which caused such consternation immediately before the sailing of Nikias on the disastrous Sicilian expedition in 415 B.C. The superstitious and fearful aspect of ancient religion is represented by the grotesque faces called apotropaia, “turners away,” which were thought to avert misfortune. They were worn especially by children, and large ones of various materials were often fastened up in workshops and houses. A number of small examples in glass.

The Greeks believed that The gods desired worship and sacrifice, and, as it could not be left to chance whether some one person would supply these, since there must be no interruption to the worship. They also believed the gods could see everything that humans did and could, if they choose, fulfill such needs as food, shelter and clothing as well as wants like love, wealth and victory. They sought the protection of the gods from their enemies, disease and the forces of nature. Prayers often begin “by identifying the god/goddess being petitioned, and the realm for which he or she was responsible. Former requests are mentioned, the results and the offerings made. Then the new request is presented for consideration. [Source: Canadian Museum of History ]

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth”

by Walter Burkert and Peter Bing (1972) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“Public Worship of the Ancient Greeks and Romans” by E. M. Berens, Gregory Zorzos (2009) Amazon.com;

“Savage Energies: Lessons of Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece” by Walter Burkert (2001) Amazon.com;

“Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion” by Matthew Dillon (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Greek Religion; Archaic and Classical Periods” by Walter Burkert (1985) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“On Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (Cornell Studies) (2011) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Religion” by Martin P. Nilsson (1925) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of the Gods” by Jacquetta Hawkes (1968) Amazom.com

“The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion” by Martin. Nilsson (1968) Amazon.com;

“Religions of the Hellenistic-Roman Age” by Antonia Tripolitis (2001) Amazon.com;

Priests in Ancient Greece

There was no formal priesthood in Ancient Greece. There were leaders of local cults and priests who worked at specific temples, who were paid by donations to the temples. Many religious rituals in ancient Greece could be performed by individuals either at a temple or elsewhere without a priest. The priest existed, in the first place, for the sake of the god, and only in the second in order to facilitate the intercourse between god and man. The gods desired worship and sacrifice, and, as it could not be left to chance whether some one person would supply these, since there must be no interruption to the worship, it was necessary to have a class of men whose work in life was the performance of these duties towards the divinity. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

It was probably this idea which led them to appoint a priestly class; and it was only as a consequence of this that laymen sometimes called upon the help of the priest, especially in important cases, since these men, who were in constant intercourse with the gods, were assumed to have the most accurate knowledge of the forms well-pleasing to the divinities. Consequently, as the development of civilisation made greater claims on ordinary people in their professional activity, such as military service, politics, studies, etc., and thus drew them away from divine things, it became commoner to make use of the mediatory assistance of the priest, and thus the influence and importance of the priestly class continued to increase. There was another reason which led the laymen to make use of the priests. According to Greek belief, the gods revealed their will to mankind by various signs and visions; it was not everyone, however, who knew how to interpret these signs; a deep knowledge of the divine nature and will, as well as a rich treasure of experience were required, and it was, therefore, natural that they turned for this purpose to those who had devoted their whole life to discovering the will of the gods. These were the seers or interpreters who were closely connected with the priests, though they must not be identified with them.

When we speak of a priestly class among the Greeks, we must not take it in the literal sense of the word; the Greek priests did not constitute a class in our modern sense of the word, since there were no preliminary studies required for the office. Greek religion possessed no dogmas; the priest’s duty was only to perform certain rites and ceremonies, and these were easily learnt. Consequently, the priesthood in Greece was limited to no age and no sex; boys and girls, youths and maidens, men and married women could perform priestly functions for a long or short period. The essential requirement was legitimate birth and participation in the community in which the priestly functions had to be performed; bodily purity and moral character were also required; members of ancient and noble families were especially privileged, and sometimes bodily strength and beauty were regarded in the choice. Generally speaking, however, the requirements made differed not only according to the gods in whose service they were to stand, but also according to local or other accidental circumstances. Thus sometimes priestesses were required to be virgins, if not for their whole life, at any rate for the duration of their priesthood; in other cases, however, married women might undertake the priestly functions. The same held good for the men. Although, as a rule, priests entered for their whole life, yet it sometimes happened that their priestly functions were only performed for a time, as for instance, in the case of boys or girls who entered the service of the temple until they attained their man or womanhood, or in other cases where citizens were made priests for one or several years, and, when the time was up, retired again and let others take their place.

There were various modes of appointing priests. They were either elected from among several candidates, in which case the right of election lay with the citizens or their representatives, or else by lot, or the right was given from birth. Certain priesthoods were hereditary in families; either the first-born was appointed as such, or else the lot had to decide between the various members of a family; sometimes, if disputes ensued, a legal decision might even be given. Consequently, it is clear that the priests in Greece did not form a special caste, and as they very often retired again to private life, their influence was not extensive or very important.

Duties of Priests in Ancient Greece

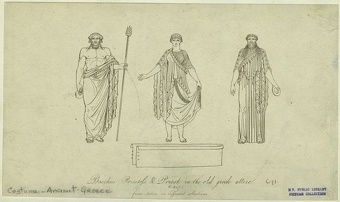

statue of a priestess

The duties of the priests consisted, in the first instance, in performing those acts of worship to the divinity which might also be performed by any layman — viz., prayers and sacrifices; and in the second, those which belonged to the worship of the particular divinity, and recurred at certain fixed periods, and particularly those which they undertook at the request of others. Besides this, there were various duties connected with the care of the temple and divine images, the fulfilment of the various customs connected with the worship of each divinity, the performance of mysterious dedications and purifications, guarding of the temple treasure, etc. To this were due various ordinances concerning their mode of life, food, clothing, etc. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Their persons were regarded as sacred, just as the sanctuary was, and they also received their share in the adoration paid to the gods, being regarded, in a measure, as their representatives. Very often they had a house in the temple domain, and received a share of its income, which had, in the first instance, to supply the means for performing the service of the god, erecting necessary buildings, statues, etc., but which often supplied the priests also with considerable profit; thus, the skins and certain parts of the sacrificial animals fell to their lot. In some of the sanctuaries the income derived from the temple property and the money lent out for interest from the temple treasure, was very considerable, and far exceeded the means required for the maintenance of the sanctuary and the service of the god. Another privilege enjoyed by the priests was the right of occupying places of honour in the theatre and at public meetings. They were usually distinguished by their dress from the rest of the citizens; they wore the long chiton, which had gone out of fashion for ordinary people; it was generally of white or purple colour, and they had wreaths and fillets in their long hair, and probably carried a staff as a token of dignity.

The priests were assisted in their duties in the temples by a large number of attendants and servants. Some of these only took part occasionally in a procession or sacrifice, and, as this was regarded as an honour, they gave their service without return. Some were permanent temple servants, who either performed for pay certain menial services connected with the worship and the care of the temple, or else were slaves and the property of the god. Among these were included the so-called “temple-sweepers” (νεωκόροι), men and women whose duty it was to clean and care for the temple. There were also heralds, sacrificial servants, butchers, bearers of the sacred vessels, singers and musicians, etc., concerning whom inscriptions give us a good deal of information. Even these positions, so long as the services to be performed were not menial but honourable, were an object of ambition to citizens, or regarded as a valuable privilege inherited by certain families; thus, for instance, at Olympia, the descendants of Pheidias had charge of the statue of Zeus, which was the masterpiece of their ancestor.

Priestesses in Ancient Greece

María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: Women who participated in religious cults and sacred rites as priestesses enjoyed life outside the domestic sphere. Archaeologist Joan Breton Connelly’s work has found that in the Greek world “religious office presented the one arena in which Greek women assumed roles equal and comparable to those of men.” [Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

Religious participation was open to young girls. The arrephoroi, for example, were young acolytes who had various ritual tasks, among them weaving the peplos (outer garment) that was dedicated each year to the goddess Athena. Girls between the age of five and adolescence could be selected to serve as “little bears” in rituals dedicated to the goddess Artemis in her sanctuary at Brauron (located about 24 miles southeast of Athens).

Priestesses played important parts in sacred festivals, some of which were predominantly, even exclusively, female. Many of these were associated with the harvest. At the Thesmophoria festival, women gathered to worship Demeter, goddess of agriculture, and her daughter, Persephone. During the Dionysiac festival of the Lenaea, women joined orgiastic rituals as maenads (mad ones), to celebrate Dionysus, god of wine.

Serving as a priestess gave women very high status. In Athens, perhaps the most important religious role was being high priestess of the Athena Polias, who in her role could be granted rights and honors unavailable to most women: One second-century B.C. priestess of Athena was granted by the city of Delphi freedom from taxes, the right to own property, and many others. Names of priestesses were well known enough to be used by ancient historians to place key events in context. Historian Thucydides marks the beginnings of the Peloponnesian War with the tenure of Chrysis, a priestess of the goddess Hera at Argos around 423 B.C., alongside the names of contemporary Athenian and Spartan officials.

Another highly significant female figure in Greek religion was the Pythia, Apollo’s high priestess at his temple in Delphi. Also known as the Oracle of Delphi, she held one of the most prestigious roles in ancient Greece. Men would come from all over the ancient world to consult with her, as they believed the god Apollo spoke through her mouth.

See Powerful Priestesses Under STRONG WOMEN IN ANCIENT GREECE: GODDESSES, LEADERS europe.factsanddetails.com ; ORACLES IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; ORACLE IN DELPHI: PYTHIA, TEMPLE, VAPORS europe.factsanddetails.com

Prayers in Ancient Greece

Prayer, either to all the gods together or to some single one, consecrated the beginning and end of the day; combined with libations, it attended the beginning and end of the meals, and was, in fact, an essential part of every important action of daily life. These prayers were, of course, of a general character, but there were other occasions when special prayers were used, adapted to particular cases; thus it was a matter of course that in the assemblies of the people the blessing of the god should be invoked on the discussion. When they set out to war they called on the help of the god in the coming fight, and similarly private citizens asked for divine aid in their undertakings and help in difficulties, though some wiser men — and especially those who had had a philosophical training — could not disguise from themselves that it was a foolish hope to expect that their prayers should necessarily be heard, and they looked upon prayer rather as a religious consecration of human actions. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

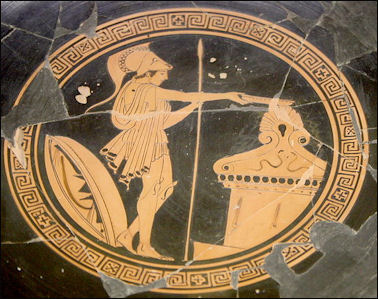

Sacrifice Kneeling and folding the hands were unknown to the ancients. In praying they stood and stretched out their hands to the region which they supposed to be the dwelling of the godhead invoked; thus, they held them upward when praying to one of the Olympian deities, forward when praying to a sea god, and down to the ground if the prayer was addressed to one of the infernal deities, at the same time trying to attract his attention by stamping on the ground. The commonest position was towards the east; when they prayed in the temple they turned towards the altar and the statue of the god, and sometimes even embraced the altar. In fact, the worship of the temple statues led to a very sensual conception of prayer; they not only threw kisses to the god they were worshipping, but even touched or kissed his statue; while suppliants threw themselves on the ground before the temple image, or at any rate knelt down before it.

Ancient inscriptions and surviving writings show that the prayer usually sounded something like this: ‘Oh Great Poseidon, brother of Zeus, Lord and Ruler of the Seas, I call on you to help me once again. Last year I asked you to protect my ship and its crew during that violent storm. You made the waters tranquil almost immediately and I honored your name with offerings in your temple. This time, on the day of the month sacred to you, I am beginning a long voyage to a distant land and I seek your blessings for fair weather and calm seas. At dawn today I ask you to accept this offering.’ “According to an ancient Greek myth it was the titan Prometheus who was instrumental in determining the nature of the offerings to be made to the gods. He made up two bundles from the body of a sacrificed animal. In the smaller bundle he put all the choice cuts of meat. In the larger, he put the bones of the animal and covered it with fat. Zeus was asked to select the portion that should always be offered to the gods. Zeus quickly, and rashly, selected the larger bundle finding out later that he had passed up on the better portion.” |

Criticism of Prayer

Persius wrote in Satire II (A.D. 60): “Mark this day, Macrinus, with a white stone, which, with auspicious omen, augments your fleeting years. Pour out the wine to your Genius! "A sound mind, a good name, integrity" — for these he prays aloud, and so that his neighbor may hear. But in his inmost breast, and beneath his breath, he murmurs thus, "Oh that my uncle would evaporate! what a splendid funeral! and oh that by Hercules' good favor a jar of silver would ring beneath my rake! or, Would that I could wipe out my ward, whose heels I tread on as next heir! For he is scrofulous, and swollen with acrid bile. [Source: The Satires of Juvenal, Persius, Sulpicia, and Lucilius, translated by Lewis Evans (London: Bell & Daldy, 1869), pp. 217-224

“This is the third wife that Nerius is now taking home!" — That you may pray for these things with due holiness, you plunge your head twice or thrice of a morning in Tiber's eddies, and purge away the defilements of night in the running stream.....You ask vigor for your sinews, and a frame that will insure old age. Well, so be it. You are eager to amass a fortune, by sacrificing a bull and court Mercury's favor by his entrails. "Grant that my household gods may make me lucky! Grant me cattle, and increase to my flocks!" Yet still he strives to gain his point by means of entrails and rich cakes. "Now my land, and now my sheepfold teems. Now, surely now, it will be granted!"

Purification in Ancient Greece

In order to ensure the efficacy of the prayer, those who offered it must be free from every bodily and moral taint and, therefore, if necessary, submit to purification. There were a number of occasions which rendered a man unclean and unfit for intercourse with the deity; such were birth and death, which required the purification of all those who had come in contact with the mother or the dead person, not only in order that they might appear untainted before the deity, but also to prevent their communicating their impurity to others, and to enable them once more to enter into intercourse with human beings.Even apart from these special occasions it was impossible to tell whether some accidental contact might have produced impurity, and on this account it was usual to precede the act of prayer by washing, or, at any rate, by a symbolical purification, such as sprinkling with holy water. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Even apart from these special occasions it was impossible to tell whether some accidental contact might have produced impurity, and on this account it was usual to precede the act of prayer by washing, or, at any rate, by a symbolical purification, such as sprinkling with holy water. For this purpose a vessel with holy water and a whisk for sprinkling were placed in the entrance of every temple for the use of those who entered the domain; similar arrangements were made in private houses, and preference was given to flowing water, especially sea-water, which was supposed to have special purifying power; for sprinkling they used a branch of some sacred tree, such as laurel.

This purification was extended not only to the person of those who approached the divinity, but also to their garments and the utensils used for prayer and sacrifice, as well as the dwelling generally; consequently, purification by fire and smoke — especially by means of burnt sulphur — played an important part along with the washing. There were also certain plants to which a purifying power was ascribed; thus, it was customary to hang up a sea-leek over the house door. Purification of this kind was, of course, even more necessary when some actual crime, such as a murder, even if an accidental one, had been committed, or any other action performed which would render a man unfit to come into the presence of the deity.

Ancient Greek Religious Rituals

Purification rituals often featured animal sacrifices, libation of wines and wine drinking. Sacrificing a dog, cock or pig was seen as a sign of purification as was bathing in the sea. Apollo was depicted on vases as performing purification by dipping laurel leaves in the bowl most likely of pig's blood. Scapegoats were of form of purification. The term is traced back to Biblical times to describe a goat representing all the sins of the people was killed.

In some rituals initiates were covered in plaster and then coated again after they died so they would be recognized in the Underworld as someone with a ticket to paradise. Greek pilgrims that visited a temple dedicated to Aphrodite's son Eryx cavorted with prostitute-priestesses.

Religious cults had their own rituals. The cult that honored the mythical singer Orpheus performed purification rituals that promised a life in paradise after death. "Orphic purifiers traveled the countryside," a German scholar told National Geographic, "Those wandering charismatics had books of poems supposedly written by Orpheus and gold leaves bearing the instructions for getting through the Underworld ."

Plutarch on Strange Ancient Greek Rituals

Plutarch wrote in “Life of Alcibiades”(c. A.D. 110): “After the people had adopted this motion and all things were made ready for the departure of the fleet, there were some unpropitious signs and portents, especially in connection with the festival, namely, the Adonia. This fell at that time, and little images like dead folk carried forth to burial were in many places exposed to view by the women, who mimicked burial rites, beat their breasts, and sang dirges. Moreover, the mutilation of the Hermai, most of which, in a single night, had their faces and phalli disfigured, confounded the hearts of many, even among those who usually set small store by such things. They looked on the occurrence with wrath and fear, thinking it the sign of a bold and dangerous conspiracy. They therefore scrutinized keenly every suspicious circumstance, the council and the assembly convening for this purpose many times within a few days.” [Source: Plutarch, “Plutarch’s Lives,” translated by John Dryden, (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910)

Plutarch wrote in “The Life of Theseos” (c. A.D. 110): “The feast called Oschophoria, or the feast of boughs, which to this day the Athenians celebrate, was then first instituted by Theseos. For he took not with him the full number of virgins which by lot were to be carried away [to the Labyrinth], but selected two youths of his acquaintance, of fair and womanish faces, but of a manly and forward spirit, and having, by frequent baths, and avoiding the heat and scorching of the sun, with a constant use of all the ointments and washes and dresses that serve to the adorning of the head or smoothing the skin or improving the complexion, in a manner changed them from what they were before, and having taught them farther to counterfeit the very voice and carriage and gait of virgins so that there could not be the least difference perceived, he, undiscovered by any, put them into the number of the Athenian virgins designated for Crete. At his return, he and these two youths led up a solemn procession, in the same habit that is now worn by those who carry the vine-branches. Those branches they carry in honor of Dionysos and Ariadne, for the sake of their story before related; or rather because they happened to return in autumn, the time of gathering the grapes.

“The women, whom they call Deipnopherai, or supper-carriers, are taken into these ceremonies, and assist at the sacrifice, in remembrance and imitation of the mothers of the young men and virgins upon whom the lot fell, for thus they ran about bringing bread and meat to their children; and because the women then told their sons and daughters many tales and stories, to comfort and encourage them under the danger they were going upon, it has still continued a custom that at this feast old fables and tales should be told. There was then a place chosen out, and a temple erected in it to Theseos, and those families out of whom the tribute of the youth was gathered were appointed to pay tax to the temple for sacrifices to him. And the house of the Phytalidai had the overseeing of these sacrifices, Theseos doing them that honor in recompense of their former hospitality.

Herodotus on the Trial of Ordeal of the Getae

Herodotus wrote in Histories IV, 93-6: The Getae “pretend to be immortal’ and are “the bravest and most just Thracians of all. Their belief in their immortality is as follows: they believe that they do not die, but that one who perishes goes to the deity Salmoxis, or Gebeleïzis, as some of them call him. Once every five years they choose one of their people by lot and send him as a messenger to Salmoxis, with instructions to report their needs; and this is how they send him: three lances are held by designated men; others seize the messenger to Salmoxis by his hands and feet, and swing and toss him up on to the spear-points. If he is killed by the toss, they believe that the god regards them with favor; but if he is not killed, they blame the messenger himself, considering him a bad man, and send another messenger in place of him. It is while the man still lives that they give him the message. Furthermore, when there is thunder and lightning these same Thracians shoot arrows skyward as a threat to the god, believing in no other god but their own. [Source: Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920]

Thracian peltast

“I understand from the Greeks who live beside the Hellespont and Pontus, that this Salmoxis was a man who was once a slave in Samos, his master being Pythagoras son of Mnesarchus; [2] then, after being freed and gaining great wealth, he returned to his own country. Now the Thracians were a poor and backward people, but this Salmoxis knew Ionian ways and a more advanced way of life than the Thracian; for he had consorted with Greeks, and moreover with one of the greatest Greek teachers, Pythagoras; therefore he made a hall, where he entertained and fed the leaders among his countrymen, and taught them that neither he nor his guests nor any of their descendants would ever die, but that they would go to a place where they would live forever and have all good things. [Source: Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920]

“While he was doing as I have said and teaching this doctrine, he was meanwhile making an underground chamber. When this was finished, he vanished from the sight of the Thracians, and went down into the underground chamber, where he lived for three years, while the Thracians wished him back and mourned him for dead; then in the fourth year he appeared to the Thracians, and thus they came to believe what Salmoxis had told them. Such is the Greek story about him. Now I neither disbelieve nor entirely believe the tale about Salmoxis and his underground chamber; but I think that he lived many years before Pythagoras; and as to whether there was a man called Salmoxis or this is some deity native to the Getae, let the question be dismissed.”

Wild Religious Festivals in Ancient Greece

To pay their respect to Dionysus, the citizens of Athens, and other city-states, held a winter-time festival in which a large phallus was erected and displayed. After competitions were held to see who could empty their jug of wine the quickest, a procession from the sea to the city was held with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and maenads (nymphs), which were often paired together. At the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

_02.jpg) The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of iv and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of iv and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The main purveyors of the Dionysus fertility cult "These drunken devotees of Dionysus," wrote Boorstin, "filled with their god, felt no pain or fatigue, for they possessed the powers of the god himself. And they enjoyed one another to the rhythm of drum and pipe. At the climax of their mad dances the maenads, with their bare hands would tear apart some little animal that they had nourished at their breast. Then, as Euripides observed, they would enjoy 'the banquet of raw flesh.' On some occasions, it was said, they tore apart a tender child as if it were a fawn'"μ

There were two major festival for Athenian women every year: The Thesmophoria promoted fertility and honored Persephone with piglet sacrifices and the offering of mass-produced statues of the goddess to receive her blessing. The Adonia honored Aphrodite's lover Adonis. It was a riotous festival in which lovers had openly licentious affairs and seeds were planting to mark the beginning of the planting season.

During Thesmophoria, an annual Athenian event to honor Demeter and Persephone, women and men who required to abstain from sex and fast for three days. Women erected bowers made of branches and sat there during their fast. On the third day they carried serpent-shaped images thought to have magical powers and entered caves to claim decayed bodied of piglets left the previous years. Pigs were sacred animals to Demeter. The piglet remains were laid on an Thesmphoria altar with offerings, launching a party with feasting, dancing and praying. This rite also featured little girls dressed up as bears.

See Separate Article: DIONYSUS CULT europe.factsanddetails.com ; FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Sacrifices

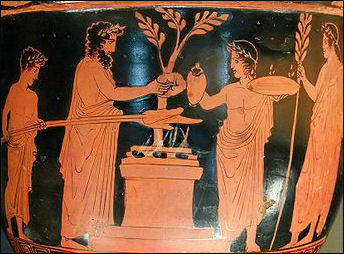

Sacrifices were the principal Greek religious ritual. They were often conducted at outdoor altars at temples to gain favor with the gods. Animals were also often sacrificed at religious festivals and sporting events, with different animals being sacrificed at different events. The spilling of blood during a ritual is believed to have magic powers. The haunch of the animal was often offered to the gods along with prayers, requests or favors, pleas for mercy or protection from harm.

Sacrificial hammer According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The central ritual act in ancient Greece was animal sacrifice, especially of oxen, goats, and sheep. Sacrifices took place within the sanctuary, usually at an altar in front of the temple, with the assembled participants consuming the entrails and meat of the victim. Liquid offerings, or libations, were also commonly made. Religious festivals, literally feast days, filled the year. The four most famous festivals, each with its own procession, athletic competitions, and sacrifices, were held every four years at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia. These Panhellenic festivals were attended by people from all over the Greek-speaking world. Many other festivals were celebrated locally, and in the case of mystery cults, such as the one at Eleusis near Athens, only initiates could participate. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Animal sacrifices were performed with great care. One slip could spoil the whole thing. The choice of animals, methods of sacrifices used and the prayers and names invoked were all carefully selected. Before a sacrifice water was sprinkled on the brow of the animal. When the animals tried to shake it off it was viewed as a sign of assent. Whoever wished to consult an oracle had to offer a bull, a goat or a wild boar as a sacrifice.

Herodotus on Greek Religious Practices in Egypt

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”:“Formerly, in all their sacrifices, the Pelasgians (pre-classical Greeks) called upon gods without giving name or appellation to any (I know this, because I was told at Dodona); for as yet they had not heard of such. They called them gods from the fact that, besides setting everything in order, they maintained all the dispositions. Then, after a long while, first they learned the names of the rest of the gods, which came to them from Egypt, and, much later, the name of Dionysus; and presently they asked the oracle at Dodona about the names; for this place of divination, held to be the most ancient in Hellas, was at that time the only one. When the Pelasgians, then, asked at Dodona whether they should adopt the names that had come from foreign parts, the oracle told them to use the names. From that time onwards they used the names of the gods in their sacrifices; and the Greeks received these later from the Pelasgians. 53. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“But whence each of the gods came to be, or whether all had always been, and how they appeared in form, they did not know until yesterday or the day before, so to speak; for I suppose Hesiod and Homer flourished not more than four hundred years earlier than I; and these are the ones who taught the Greeks the descent of the gods, and gave the gods their names, and determined their spheres and functions, and described their outward forms. But the poets who are said to have been earlier than these men were, in my opinion, later. The earlier part of all this is what the priestesses of Dodona tell; the later, that which concerns Hesiod and Homer, is what I myself say. 54.

“The fashions of divination at Thebes of Egypt and at Dodona are like one another; moreover, the practice of divining from the sacrificed victim has also come from Egypt. 58. It would seem, too, that the Egyptians were the first people to establish solemn assemblies, and processions, and services; the Greeks learned all that from them. I consider this proved, because the Egyptian ceremonies are manifestly very ancient, and the Greek are of recent origin. 59.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024