Home | Category: Religion / Art and Architecture

ACROPOLIS

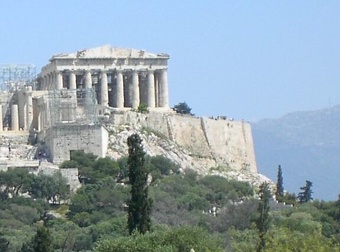

The Acropolis is the name of the huge rock in Ayhens on which the Parthenon stands. Anchored by huge walls and surrounded by a forest of unassembled ruins the Acropolis rises out of Athens like a miniature Mt. Olympus. An important secular and sacred site, it was home to he city's treasury as well as temples for religious rites and sacrifices.

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: For thousands of years the monuments of the Athenian Acropolis have been regarded not only as examples of extraordinary skill and beauty, but also as potent symbols of religious devotion and civic and national identity. “Although there were many important sanctuaries and public spaces in Athens and across Attica,” says classical art historian Jeffrey Hurwit of the University of Oregon, “the Acropolis stands as what might be called the central repository of Athenians’ conceptions of themselves. These monuments and sculptures presented images of the gods and goddesses — Athena herself above all — and also of the Athenians and their heroes.” The intention, says Hurwit, was to represent Athens as the greatest of Greek cities and the Athenians as the greatest of Greeks. “To walk through the classical Acropolis was to traverse a marble paean to Athens itself,” he says. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

“The Acropolis rises nearly 152 meters (500 feet) above the Ilissos Valley, measures about 110 meters (360 feet) north to south and 250 meters (820 feet) east to west, and has a surface area of about three hectares (seven and a half acres). The site was leveled with artificial fill, in places as much as 17 meters (55 feet) thick, to create a surface upon which to build. Atop it sit the four major standing structures dating to the city’s massive building program of the fifth century B.C., initiated after the destruction of earlier monuments in 480 B.C. by the Persians: the Propylaia, Temple of Athena Nike, Erechtheion, and Parthenon.

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES, SANCTUARIES AND SACRED PLACES europe.factsanddetails.com ; FAMOUS ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Parthenon” (Wonders of the World)

by Mary Beard Amazon.com;

“The Parthenon: The Height of Greek Civilization” (Wonders of the World Book) by Elizabeth Mann (Author), Yuan Lee (Illustrator) (2025) Amazon.com;

“Parthenon Sculptures” by Ian Jenkins Amazon.com;

“The Complete Greek Temples” by Tony Spawforth (2006) Amazon.com;

“Origins of Classical Architecture: Temples, Orders, and Gifts to the Gods in Ancient Greece” by Mark Wilson Jones (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Earth, the Temple, and the Gods: Greek Sacred Architecture” by Vincent Scully (1979 Amazon.com;

“Greek Sanctuaries and Temple Architecture: An Introduction” by Mary Emerson (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Optical Corrections of the Doric Temple: Form and Meaning in Greek Sacred Architecture” by Tapio Uolevi Prokkola (2011) Amazon.com;

“Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth”

by Walter Burkert and Peter Bing (1972) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“Smoke Signals for the Gods: Ancient Greek Sacrifice from the Archaic Through Roman Periods” by F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion” by Martin. Nilsson (1968) Amazon.com;

History of the Acropolis

Caves near a natural spring on the steep north side of the Acropolis have been inhabited since Neolithic times and the fortress-like walls around the Acropolis were built by the Mycenaeans to protect a palace they had erected at the top. This was superseded by a Greek temple dedicated to Poseidon and Athena that was destroyed in 480 B.C. when the entire city of Athens was burned to ground by the Persian army of Xeres. In the Golden Age of Greece the caves contained a shrine to Pan and other Gods.

From the Acropolis , it is easy to see why this abrupt steep-sided rock was chosen as the first citadel of ancient Athens: it is a superb natural defensive site. Once fortified, it was virtually impregnable, although defenders were hampered by the lack of water on the Acropolis . Still, the Acropolis was a fitting home for the virgin warrior goddess, Athena. [Source: Internet Archive, from vacation.net.gr]

Many of the temples built on the Acropolis were shrines to Athena, as is the Parthenon which remains today. Its predecessor, the massive Hekatompedon of Peisistratus, was located slightly to the north of the Parthenon, beside the present Erechtheion. The Hekatompedon (also known as the "Old Temple of Athena"), was burnt in the Persian sack of Athens in 480 B.C. Its foundations remain on the Acropolis , and are the only remnants of the buildings which were on the Acropolis before the Persians sacked the city. Parts of the temple were built into the north wall of the Acropolis , where some of the massive column drums may still be seen.

However grand the buildings with which Peisistratos adorned the Acropolis , they did not survive the Persian onslaught. Fortunately, many of the buildings erected by Pericles a half century later have survived, and it is the Periclean Acropolis which we visit today. Of these buildings, the most famous is the Parthenon (447-32 B.C.), flanked by the temple of Athena Nike (427-24 B.C.) and the Erechtheion (421-06 B.C.). In addition, Pericles was responsible for the building of the Propylaia (437-32 B.C.), the monumental entrance way to the Acropolis .

Monuments of the Acropolis

According to UNESCO: “The Acropolis of Athens and its monuments are universal symbols of the classical spirit and civilization and form the greatest architectural and artistic complex bequeathed by Greek Antiquity to the world. In the second half of the fifth century B.C. Athens, following the victory against the Persians and the establishment of democracy, took a leading position amongst the other city-states of the ancient world. In the age that followed, as thought and art flourished, an exceptional group of artists put into effect the ambitious plans of Athenian statesman Pericles and, under the inspired guidance of the sculptor Pheidias, transformed the rocky hill into a unique monument of thought and the arts. The most important monuments were built during that time: the Parthenon, built by Ictinus, the Erechtheon, the Propylaea, the monumental entrance to the Acropolis, designed by Mnesicles and the small temple Athena Nike. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

Zeus Temple in Athens

“The Acropolis of Athens is the most striking and complete ancient Greek monumental complex still existing in our times. It is situated on a hill of average height (156 meters, 510 feet) that rises in the basin of Athens. Its overall dimensions are approximately 170 by 350 meters (560 by 1150 feet). The hill is rocky and steep on all sides except for the western side, and has an extensive, nearly flat top. Strong fortification walls have surrounded the summit of the Acropolis for more than 3,300 years. The first fortification wall was built during the 13th century B.C. and surrounded the residence of the local Mycenaean ruler. In the 8th century B.C. the Acropolis gradually acquired a religious character with the establishment of the cult of Athena, the city’s patron goddess. The sanctuary reached its peak in the archaic period (mid-6th century to early 5th century B.C.). In the 5th century B.C. the Athenians, empowered from their victory over the Persians, carried out an ambitious building programme under the leadership of the great statesman Perikles, comprising a large number of monuments including the Parthenon, the Erechtheion, the Propylaia and the temple of Athena Nike.

The monuments were developed by an exceptional group of architects (such as Iktinos, Kallikrates, Mnesikles) and sculptors (such as Pheidias, Alkamenes, Agorakritos), who transformed the rocky hill into a unique complex, which heralded the emergence of classical Greek thought and art. On this hill were born Democracy, Philosophy, Theatre, Freedom of Expression and Speech, which provide to this day the intellectual and spiritual foundation for the contemporary world and its values. The Acropolis’ monuments, having survived for almost twenty-five centuries through wars, explosions, bombardments, fires, earthquakes, sackings, interventions and alterations, have adapted to different uses and the civilizations, myths and religions that flourished in Greece through time.”

Why the Acropolis Is So Special

According to UNESCO: “The Athenian Acropolis is the supreme expression of the adaptation of architecture to a natural site. This grand composition of perfectly balanced massive structures creates a monumental landscape of unique beauty, consisting of a complete series of architectural masterpieces of the 5th century B.C.: the Parthenon by Iktinos and Kallikrates with the collaboration of the sculptor Pheidias (447-432); the Propylaia by Mnesikles (437-432); the Temple of Athena Nike by Mnesikles and Kallikrates (427-424); and Erechtheion (421-406). [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“The monuments of the Athenian Acropolis have exerted an exceptional influence, not only in Greco-Roman antiquity, during which they were considered exemplary models, but also in contemporary times. Throughout the world, Neo-Classical monuments have been inspired by all the Acropolis monuments. =

“From myth to institutionalized cult, the Athenian Acropolis, by its precision and diversity, bears a unique testimony to the religions of ancient Greece. It is the sacred temple from which sprung fundamental legends about the city. Beginning in the 6th century B.C. myths and beliefs gave rise to temples, altars and votives corresponding to an extreme diversity of cults, which have brought us the Athenian religion in all its richness and complexity. Athena was venerated as the goddess of the city (Athena Polias); as the goddess of war (Athena Promachos); as the goddess of victory (Athena Nike); as the protective goddess of crafts (Athena Ergane), etc. Most of her identities are glorified at the main temple dedicated to her, the Parthenon, the temple of the patron-goddess. =

“The Athenian Acropolis is an outstanding example of an architectural ensemble illustrating significant historical phases since the 16th century B.C. . Firstly, it was the Mycenaean Acropolis (Late Helladic civilization, 1600-1100 B.C.) which included the royal residence and was protected by the characteristic Mycenaean fortification. The monuments of the Acropolis are distinctly unique structures that evoke the ideals of the Classical 5th century B.C. and represent the apex of ancient Greek architectural development. =

“The Acropolis is directly and tangibly associated with events and ideas that have never faded over the course of history. Its monuments are still living testimonies of the achievements of Classical Greek politicians (e.g. Themistokles, Perikles) who lead the city to the establishment of Democracy; the thought of Athenian philosophers (e.g. Socrates, Plato, Demosthenes);and the works of architects (e.g. Iktinos, Kallikrates, Mnesikles) and artists (e.g. Pheidias, Agorakritus, Alkamenes). These monuments are the testimony of a precious part of the cultural heritage of humanity. =

Temple of Zeus in Athens in the A.D. 2nd Century

In ancient times before one arrived at the Acropolis and The Parthenon one came to the Temple of Zeus. Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “Before the entrance to the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus” is “the statue, one worth seeing, which in size exceeds all other statues save the colossi at Rhodes and Rome, and is made of ivory and gold with an artistic skill which is remarkable when the size is taken into account...Before the pillars stand bronze statues which the Athenians call "colonies." The whole circumference of the precincts is about four stades, and they are full of statues” from “every city... and the Athenians have surpassed them in dedicating, behind the temple, the remarkable colossus.[Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Within the precincts are antiquities: a bronze Zeus, a temple of Cronus and Rhea and an enclosure of Earth surnamed Olympian. Here the floor opens to the width of a cubit, and they say that along this bed flowed off the water after the deluge that occurred in the time of Deucalion, and into it they cast every year wheat meal mixed with honey. On a pillar is a statue of Isocrates, whose memory is remarkable for three things: his diligence in continuing to teach to the end of his ninety-eight years, his self-restraint in keeping aloof from politics and from interfering with public affairs, and his love of liberty in dying a voluntary death, distressed at the news of the battle at Chaeronea1. There are also statues in Phrygian marble of Persians supporting a bronze tripod; both the figures and the tripod are worth seeing. The ancient sanctuary of Olympian Zeus the Athenians say was built by Deucalion, and they cite as evidence that Deucalion lived at Athens a grave which is not far from the present temple.

“Close to the temple of Olympian Zeus is a statue of the Pythian Apollo. There is further a sanctuary of Apollo surnamed Delphinius. The story has it that when the temple was finished with the exception of the roof Theseus arrived in the city, a stranger as yet to everybody. When he came to the temple of the Delphinian, wearing a tunic that reached to his feet and with his hair neatly plaited, those who were building the roof mockingly inquired what a marriageable virgin was doing wandering about by herself. The only answer that Theseus made was to loose, it is said, the oxen from the cart hard by, and to throw them higher than the roof of the temple they were building.

“Concerning the district called The Gardens, and the temple of Aphrodite, there is no story that is told by them, nor yet about the Aphrodite which stands near the temple. Now the shape of it is square, like that of the Hermae, and the inscription declares that the Heavenly Aphrodite is the oldest of those called Fates. But the statue of Aphrodite in the Gardens is the work of Alcamenes, and one of the most note worthy things in Athens. There is also the place called Cynosarges, sacred to Heracles; the story of the white dog1 may be known by reading the oracle. There are altars of Heracles and Hebe, who they think is the daughter of Zeus and wife to Heracles. An altar has been built to Alcmena and to Iolaus, who shared with Heracles most of his labours. The Lyceum has its name from Lycus, the son of Pandion, but it was considered sacred to Apollo from the be ginning down to my time, and here was the god first named Lyceus.”

reconstructed Acropolis

Acropolis Area in Athens in the A.D. 2nd Century

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “After the sanctuary of Asclepius, as you go by this way towards the Acropolis, there is a temple of Themis. Before it is raised a sepulchral mound to Hippolytus. The end of his life, they say, came from curses. Everybody, even a foreigner who has learnt Greek, knows about the love of Phaedra and the wickedness the nurse dared commit to serve her. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“All the Acropolis is surrounded by a wall; a part was constructed by Cimon, son of Miltiades, but all the rest is said to have been built round it by the Pelasgians, who once lived under the Acropolis. The builders, they say, were Agrolas and Hyperbius. On inquiring who they were I could discover nothing except that they were Sicilians originally who emigrated to Acarnania.

“In addition to the works I have mentioned, there are two tithes dedicated by the Athenians after wars. There is first a bronze Athena, tithe from the Persians who landed at Marathon. It is the work of Pheidias, but the reliefs upon the shield, including the fight between Centaurs and Lapithae, are said to be from the chisel of Mys1, for whom they say Parrhasius the son of Evenor, designed this and the rest of his works. The point of the spear of this Athena and the crest of her helmet are visible to those sailing to Athens, as soon as Sunium is passed. Then there is a bronze chariot, tithe from the Boeotians and the Chalcidians in Euboea.There are two other offerings, a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and the best worth seeing of the works of Pheidias, the statue of Athena called Lemnian after those who dedicated it.

Both the city and the whole of the land are alike sacred to Athena; for even those who in their parishes have an established worship of other gods nevertheless hold Athena in honor. But the most holy symbol, that was so considered by all many years before the unification of the parishes, is the image of Athena which is on what is now called the Acropolis, but in early days the Polis (City). A legend concerning it says that it fell from heaven; whether this is true or not I shall not discuss. A golden lamp for the goddess was made by Callimachus. Having filled the lamp with oil, they wait until the same day next year, and the oil is sufficient for the lamp during the interval, although it is alight both day and night. The wick in it is of Carpasian flax, the only kind of flax which is fire-proof, and a bronze palm above the lamp reaches to the roof and draws off the smoke. The Callimachus who made the lamp, although not of the first rank of artists, was yet of unparalleled cleverness, so that he was the first to drill holes through stones, and gave himself the title of Refiner of Art, or perhaps others gave the title and he adopted it as his.

Acropolis of Athens in the A.D. 2nd Century

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “There is but one entry to the Acropolis. It affords no other, being precipitous throughout and having a strong wall. The gateway has a roof of white marble, and down to the present day it is unrivalled for the beauty and size of its stones. Now as to the statues of the horsemen, I cannot tell for certain whether they are the sons of Xenophon or whether they were made merely to beautify the place. On the right of the gateway is a temple of Wingless Victory. From this point the sea is visible, and here it was that, according to legend, Aegeus threw him self down to his death. For the ship that carried the young people to Crete began her voyage with black sails; but Theseus, who was sailing on an adventure against the bull of Minos, as it is called, had told his father beforehand that he would use white sails if he should sail back victorious over the bull. But the loss of Ariadne made him forget the signal. Then Aegeus, when from this eminence he saw the vessel borne by black sails, thinking that his son was dead, threw himself down to destruction. There is at Athens a sanctuary dedicated to him, and called the hero-shrine of Aegeus. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“On the left of the gateway is a building with pictures. Among those not effaced by time I found Diomedes taking the Athena from Troy, and Odysseus in Lemnos taking away the bow of Philoctetes. There in the pictures is Orestes killing Aegisthus, and Pylades killing the sons of Nauplius who had come to bring Aegisthus succor. And there is Polyxena about to be sacrificed near the grave of Achilles... There are other pictures, including a portrait of Alcibiades, and in the picture are emblems of the victory his horses won at Nemea. There is also Perseus journeying to Seriphos, and carrying to Polydectes the head of Medusa, the legend about whom I am unwilling to relate in my description of Attica. Included among the paintings — I omit the boy carrying the water-jars and the wrestler of Timaenetus1 — is Musaeus. Right at the very entrance to the Acropolis are a Hermes (called Hermes of the Gateway) and figures of Graces, which tradition says were sculptured by Socrates, the son of Sophroniscus, who the Pythia testified was the wisest of men, a title she refused to Anacharsis, although he desired it and came to Delphi to win it.

“Hard by is a bronze statue of Diitrephes shot through by arrows...I remember looking at other things also on the Athenian Acropolis, a bronze boy holding the sprinkler, by Lycius son of Myron, and Myron's Perseus after beheading Medusa. There is also a sanctuary of Brauronian Artemis; the image is the work of Praxiteles, but the goddess derives her name from the parish of Brauron. The old wooden image is in Brauron, the Tauric Artemis as she is called. There is the horse called Wooden set up in bronze. That the work of Epeius was a contrivance to make a breach in the Trojan wall is known to everybody who does not attribute utter silliness to the Phrygians. But legend says of that horse that it contained the most valiant of the Greeks, and the design of the bronze figure fits in well with this story. Menestheus and Teucer are peeping out of it, and so are the sons of Theseus. Of the statues that stand after the horse, the likeness of Epicharinus who practised the race in armour was made by Critius, while Oenobius performed a kind service for Thucydides the son of Olorus.1 He succeeded in getting a decree passed for the return of Thucydides to Athens, who was treacherously murdered as he was returning, and there is a monument to him not far from the Melitid gate.

“In this place is a statue of Athena striking Marsyas the Silenus for taking up the flutes that the goddess wished to be cast away for good. Opposite these I have mentioned is represented the fight which legend says Theseus fought with the so-called Bull of Minos, whether this was a man or a beast of the nature he is said to have been in the accepted story. For even in our time women have given birth to far more extraordinary monsters than this. There is also a statue of Phrixus the son of Athamas carried ashore to the Colchians by the ram. Having sacrificed the animal to some god or other, presumably to the one called by the Orchomenians Laphystius, he has cut out the thighs in accordance with Greek custom and is watching them as they burn. Next come other statues, including one of Heracles strangling the serpents as the legend describes. There is Athena too coming up out of the head of Zeus, and also a bull dedicated by the Council of the Areopagus on some occasion or other, about which, if one cared, one could make many conjectures.

“On the Athenian Acropolis is a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and one of Xanthippus him self, who fought against the Persians at the naval battle of Mycale. But that of Pericles stands apart, while near Xanthippus stands Anacreon of Teos, the first poet after Sappho of Lesbos to devote himself to love songs, and his posture is as it were that of a man singing when he is drunk. Deinomenes made the two female figures which stand near, Io, the daughter of Inachus, and Callisto, the daughter of Lycaon, of both of whom exactly the same story is told, to wit, love of Zeus, wrath of Hera, and metamorphosis, Io becoming a cow and Callisto a bear.“

Acropolis Walls

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Although people had been living on the Acropolis since the Neolithic period (ca. 4000–3200 B.C.), it was not until the Bronze Age (ca. 3200–1100 B.C.) that the rock became a fortified citadel with a palace. The first defensive wall atop the Acropolis was built in the thirteenth century B.C. by the Mycenaeans, a civilization that thrived in Greece between about 1600 and 1100 B.C. Long after the Mycenaeans were gone, their wall survived — and some sections still do — until it was severely damaged by the Persians in 480 B.C., after which a new 2,500-foot circuit wall was built as part of the fifth-century B.C. building program. In some places, pieces of monuments destroyed earlier in the century were used. [Source:Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

For more than three decades the circuit walls have been exhaustively documented, constantly maintained, and actively monitored using traditional methods, such as inspecting cracks and removing roots and plants, in combination with the latest and most accurate technology available. A complete photogrammetric survey and 3-D scan of the walls has been completed, optical fibers have been installed to measure strain, and a highly precise nickel-iron alloy underground wire has been placed between the Parthenon and the south wall to measure micromovements.

“As part of the conservation of the walls, the limestone and schist of the Acropolis itself was also consolidated. Between 1979 and 1993, unstable rocks were anchored to the main mass of the Acropolis in 22 places with stainless steel rods, and gaps and fissures in the rock were sealed with injections of cement.

The Parthenon

The Parthenon is one of the best known architectural symbols of any civilization. Built in the 15 year period between 447-432 B.C. this ancient Greek temple was designed as a replacement for a temple destroyed by the Persians in 480 B.C. . Made of Pentelic marble, it was designed by the architect Iktinos to hold the monumental gold and ivory (chryselephantine) statue of Athena designed by the sculptor-architect Pheidias. The name, "Parthenon", refers to the room where the virgin goddess Athena (Athena Parthenos), had her statue. [Source: Internet Archive, from vacation.net.gr]

The Parthenon (on the top of the Acropolis in Athens) is one of the world's most famous monuments. Dedicated to Athena Parthhenos, the Virgin, patron of Athens, and originally painted with bright colors, it was the first temple built on the Acropolis after a Persian invasion that nearly destroyed Athens, goddess of Athens.

Athenian citizen used to line the promenade of the Stoa of Attalos in the Agora to watch the Panatheenaic procession in which a huge dress was hauled up to the Acropolis as an offering to Athena. Near the Parthenon was a 30-foot-high bronze statue of Athena Promachos, the Warrior, whose metal glistened so brightly it was said it could be seen by ships approaching Athens.

The Parthenon is 70 meters (228 feet) long, 31 meters (101 feet) wide and 18 meters (60 feet) high. It has 17 outer columns on the north and south sides and eight columns at each end. It covers an area about half the size of a football field. The 46 outer columns are 11 meters (36 feet) high The main structure is built of limestone and marble. A 170 meter (558 foot) frieze once wrapped around the top of the exterior wall. The roof is missing and there are several stories as to how this happened.

See Separate Article: PARTHENON: ITS HISTORY, ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURES europe.factsanddetails.com

Other Acropolis Structures

Other Acropolis Structures include the Chalkotheke ("a place to store bronze" off the west end of the Parthenon. It's original purpose is unknown but at one time it held armor, weapons, possibly left as votive offerings. The Sanctuary Brauron (next to the Chalkotheke) once contained a huge representation of the Trojan Horse.

The Theater of Herodes Atticus (161 A.D.) is a huge well preserved amphitheater on the southern flank of the Acropolis that is the site of the Athens Festival which runs from the middle of June to the middle of September. Programs include theater, ballet, opera, chamber music and opera.

Acropolis: 1) Parthenon; 2) Old Temple of Athena; 3) Erechtheion; 4) Statue of Athena; Promachus; 5) Propylaea; 6) Temple of Athena Nike; 8) Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia; 9) Chalkotheke; 10) Pandroseion; 11) Arrephorion; 12) Altar of Athena; 13) Sanctuary of Zeus; Polieus; 14) Sanctuary of Pandion; 15) Odeon of Herodes Atticus; 16) Stoa of Eumenes; 17) Sanctuary of Asclepius; 18) Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus; 19) Odeum of Pericles; 20) Temenos of Dionysus Eleuthereus; 21) Aglaureion; 22) Peripatos; 23) Clepshydra; 24) Caves of Apollo Hypocraisus, Olympian Zeus and Pan; 25) Sanctuary of Aphrodite and Eros; 26) Peripatos inscription; 27) Cave of Aglauros; 28) Panathenaic way

The Stoa of Eumenes (168-159 B.C.) is an old arcade that looks sort of like an aqueduct that runs from the amphitheater along the eastern base of the acropolis. At the end of this wall is the Theater of Dionysus (circa 330 B.C.), another amphitheater than is not in as good a shape as Herodes Atticus.

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): ““In the temple of Athena Polias (Of the City) is a wooden Hermes, said to have been dedicated by Cecrops, but not visible because of myrtle boughs. The votive offerings worth noting are, of the old ones, a folding chair made by Daedalus, Persian spoils, namely the breastplate of Masistius, who commanded the cavalry at Plataea, and a scimitar said to have belonged to Mardonius. Now Masistius I know was killed by the Athenian cavalry. But Mardonius was opposed by the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) and was killed by a Spartan; so the Athenians could not have taken the scimitar to begin with, and furthermore the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) would scarcely have suffered them to carry it off. About the olive they have nothing to say except that it was testimony the goddess produced when she contended for their land. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Legend also says that when the Persians fired Athens the olive was burnt down, but on the very day it was burnt it grew again to the height of two cubits. Adjoining the temple of Athena is the temple of Pandrosus, the only one of the sisters to be faithful to the trust. I was much amazed at something which is not generally known, and so I will describe the circumstances. Two maidens dwell not far from the temple of Athena Polias, called by the Athenians Bearers of the Sacred Offerings. For a time they live with the goddess, but when the festival comes round they perform at night the following rites. Having placed on their heads what the priestess of Athena gives them to carry — neither she who gives nor they who carry have any knowledge what it is — the maidens descend by the natural underground passage that goes across the adjacent precincts, within the city, of Aphrodite in the Gardens. They leave down below what they carry and receive something else which they bring back covered up. These maidens they henceforth let go free, and take up to the Acropolis others in their place. By the temple of Athena is .... an old woman about a cubit high, the inscription calling her a handmaid of Lysimache, and large bronze figures of men facing each other for a fight, one of whom they call Erechtheus, the other Eumolpus; and yet those Athenians who are acquainted with antiquity must surely know that this victim of Erechtheus was Immaradus, the son of Eumolpus. On the pedestal are also statues of Theaenetus, who was seer to Tolmides, and of Tolmides himself, who when in command of the Athenian fleet inflicted severe damage upon the enemy, especially upon the Peloponnesians.”

Erechtheion

Erechtheion

The Erechtheion (421-407 B.C) (on the side of the Acropolis opposite the Acropolis Museum) is an odd shaped structure built to honor the legendary Athenian king Erechtheus as well as Poseidon and Athena. It housed a rare cult statue of Athena that been around for centuries before the temple was built. Nearby was a sacred olive tree that is said to have miraculously sprouted new growth overnight after the sacking by Persia.

The temple stands on the site of the original Poseidon and Athena temple that existed before the Persian invasion. It was built around the same time as the Parthenon as were the other buildings on top of the Acropolis. The founders creators of classical Athens, Erechtheus and Kekrops, were buried here and during the Turkish occupation it was the home of the Turkish commander's harem.

The Erechtheion is a large and complex temple that consists of two porches: a large one facing the north and a small one facing the Parthenon . The latter is supported by six female-shaped columns known as the “caryatids” . It is no wonder the Turkish governor chose this building to house his harem a thousand years later.

The Erechtheion occupies the most sacred ground on Athens’s Acropolis. Ancient Greeks held festivals, sacrifices, games, and religious processions at the site. Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “There is also a building called the Erechtheion. Before the entrance is an altar of Zeus the Most High, on which they never sacrifice a living creature but offer cakes, not being wont to use any wine either. Inside the entrance are altars, one to Poseidon, on which in obedience to an oracle they sacrifice also to Erechtheus, the second to the hero Butes, and the third to Hephaestus. On the walls are paintings representing members of the clan Butadae; there is also inside — the building is double — sea-water in a cistern. This is no great marvel, for other inland regions have similar wells, in particular Aphrodisias in Caria. But this cistern is remarkable for the noise of waves it sends forth when a south wind blows. On the rock is the outline of a trident. Legend says that these appeared as evidence in support of Poseidon's claim to the land. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

History of the Erechtheion

“In many ways, the story of the Erechtheion is the story of Athens. “The Erechtheion was a means to encompass, within its footprint, relics of early Athenian myth and religion,” says classical art historian Jeffrey Hurwit. Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: It was there that the memory of the dispute between Athena and Poseidon over the patronage of the city was preserved in what the Athenians regarded as the impression of the god’s trident, visible through a hole left in the floor of the north porch. That foundational legend was also preserved in the tales of a sea he caused to well up during the contest, long believed to be under the building, and in the olive tree that Athena caused to sprout on this spot and that marked her victory. And in this location was kept the olivewood statue of Athena Polias (Athena of the City), the Athenians’ most sacred relic, an object so ancient that not even they knew where it had come from. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

Since its construction on the Acropolis’ north side between 421 and 406 B.C., when it replaced an earlier temple to Athena, the Erechtheion — named after Erechtheus, king of Athens and foster son of Athena — has had a complicated history of use, reuse, destruction, and renovation that mirrors the history of the city. In the fifth century B.C., the unique, asymmetrical structure — its highly unusual shape largely determined by the irregular terrain — served not only as a temple to both Athena and Poseidon, but also as home to the cults of the god Hephaistos, Erechtheus, and the hero Boutes, Erechtheus’ brother. The building underwent its first major repairs after it was burned during the Roman general Sulla’s siege of Athens in the first century B.C. Since then the Erechtheion has been a church (in the early Byzantine period), a palace for the bishop (during the Frankish period), and a dwelling for the harem of the Turkish garrison commander (in the Ottoman period). Between 1801 and 1812, sculptures, including one of the six caryatids that held up the south porch, were removed to England by Lord Elgin, and during the Greek War of Independence, the ceiling of the north porch was blown up.

“The Erechtheion was the first building that Nikolaos Balanos addressed during his Acropolis restoration project, and thus the first place where he employed the techniques that were to prove so disastrous — the use of corrosive iron to reinforce fragile architectural members, the cutting and removal of ancient stones, and the haphazard placement of random fragments to fill in and restore missing sections of the ancient buildings. As a result of Balanos’ interventions and the building’s repeated recasting, much about its ancient appearance is lost. But between 1979 and 1987, 23 blocks of the north wall that had been incorrectly used to restore the south wall were replaced in their original positions, and new blocks were made for the south wall. This raised the height of the north wall by four courses, bringing it closer to its original height. Because scholars haven’t yet discovered a way to protect the surface of the marble that makes up the Acropolis’ major monuments, the remaining caryatids that supported the south porch were removed in 1978 and all were replaced with copies. The originals now sit in the Acropolis Museum, where they were recently cleaned using pulse laser ablation, the same technique that was used on the coffered ceiling of the caryatid porch and on the west frieze of the Parthenon. This technique, explains Demetrios Anglos of the Foundation for Research and Technology at the Institute of Electronic Structure and Laser in Crete, who oversaw the efforts, involves directing the laser for a short time in a highly focused way and concentrating it on a small volume of material so the dirt is removed in a nondestructive manner. “We do this to clean the marble,” Anglos explains, “and to reach a place that is acceptable from both a materials and aesthetic point of view.”

Propylaea

Propylaea (entrance to the Parthenon)

The Propylaea (437-432 B.C.) (at the western end of the Acropolis) is an elaborate structure that is half gate and half temple, forming the monumental entrance to the Acropolis. The Propylaea was commissioned by Pericles immediately after the Parthenon was finished in 437 B.C. It took five years to build and was left unfinished, probably because of the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.

The Propylaea is a splendid example of architecture blending in with the terrain. It consists of two massive stone edifices with a wide stairway in between. At the top of the stairway is a set of large Doric columns. The north wing of building houses the Pinakotheke, a large room that was used to display paintings, the first known example of an art gallery.

Entering through this gate allows one to best appreciate the Acropolis. First you walk up a short switch-backed trail. Then you walk through a huge opening in the walls. Inside the Propylaea you walk between a corridor of massive columns into a huge vault-like structure which in turn leads to the top of the Acropolis. Ancient processions used to travel this same route.

As one toils up the slopes of the Acropolis, one is aware of the mighty presence of the Propylaia, designed by the famous architect Mnesicles. The Propylaia sits on uneven terrain, on a wedge-shaped bit of the rock, whose anomalies governed the irregularities of the building itself. The terrain may have defeated the project, which was never completed. In essence, the Propylaia has a central hall flanked by two wings, one of which contained the famous Pinakotheke (Picture Gallery), with many pictures by the legendary Polygnotos. As we knew from Pausanias, the pictures were both of legendary figures such as Perseus and of historical personages Alcibiades. "Among the paintings is Alcibiades; there are symbols in the painting of his victory in the horse-race at Nemea. Perseus is on his way to Seriphos, bringing Medusa's head..."

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Ever since the mid-sixth century B.C., a monumental gateway has stood on the west side of the Acropolis at the entrance to Athena’s sanctuary. The original gate was replaced by one that was subsequently destroyed by the Persians and then repaired. The impressive structure seen today — actually three buildings on two different levels — was built between 437 and 432 B.C. by the architect Mnesikles. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

Many sections of the gate restored by Nikolaos Balanos in the early twentieth century have been dismantled, repaired, and replaced, with much of the recent work focused on the Propylaia’s once brightly painted marble coffered ceilings. Now completed, this project required arresting the deterioration of the marble resulting from the iron reinforcements used by Balanos. In addition, 24,00 architectural members needed to be properly identified — including ones that hadn’t been used in earlier restorations, fragments wrongly placed, and pieces that required their own restoration — in order to determine what needed to be fashioned anew. As with the other buildings of the Acropolis, the Propylaia was repeatedly used for purposes different from those originally intended — it has been a church, a residence for Frankish dukes, and a garrison and munitions store under the Turks. The most recent effort has succeeded in restoring the fifth-century B.C. experience of entering the Acropolis through an impressively roofed structure, as Mnesikles intended.

Temple of Athena Nike

The Temple of Nike (on one side of the Propylaea, to the right of the entrance) is a small and relatively intact marble temple honoring the God of Victory. Also known as the Temple of Athena Nike (Victorious Athena), it was built on the Acropolis in the 6th century B.C. It was destroyed by the Persians and rebuilt between 427 and 424 B.C. to celebrate Greece's victory in war.

In Mycenaean times, there was evidently a small shrine here, and Peisistratos constructed a more substantial altar, destroyed in the Persian conflagration of 480 B.C. The Periclean temple stood until it was destroyed by the Turks in 1686; happily, it was reconstructed and restored first in the 19th, and then again in the 20th centuries. The sculptural frieze of the temple, in a departure from tradition, showed not the contests of the gods, but scenes from the Battle of Plataea (479 B.C.), in which the Greeks decisively defeated the Persians. [Source: Internet Archive, from vacation.net.gr]

Some say that it was from this spot that Aegeus kept watch for his son Perseus, when he returned from Crete, after slaying the Minotaur. Others, however, believe that Aegeus kept watch from Cape Sounion, and threw himself into the sea from that cliff. Be that as it may, if the nefos is not too enveloping, one has a spectacular view across the Bay of Phaleron and the Saronic Gulf toward the mountains of the Peloponnese.

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: The small marble temple on the rock’s southwest corner dedicated to Athena Nike (Victorious Athena), was the first building on the Acropolis to be restored. In the seventeenth century, the temple was demolished and its stones used to strengthen the Turkish fortification wall. From 1836 to 1845, it was re-erected in the first of three attempts at anastylosis. Between 1935 and 1940, as part of Nikolaos Balanos’ restoration work, the temple was again dismantled and put back together, and finally, between 2000 and 2010, the most recent restoration was completed. This last required demolition and replacement of the concrete slab installed by Balanos, upon which the temple, with a stainless steel grid, as well as the complete dismantling, restoration, and resetting of all its architectural members. During this process, pieces of column drums and capitals, parts of the coffered ceiling, and blocks of the frieze, cornices, and the pediment were all put back where they had originally been. “We had the opportunity to correct mistakes in the positions of stones from the walls and columns. Balanos had put the best-looking ones in the front, even though some of them had originally been on the back,” says architect Vassiliki Eleftheriou. In addition, some fragments that had never been used in previous restorations were identified and set on the building. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

The restored temple seen today is not the only monument in this location. As part of the current project, scholars have also conserved an earlier limestone temple to Athena, probably dating to the sixth century B.C., that was discovered in 1936 and that lies beneath the later temple. This earlier structure, along with the base of the cult statue of the goddess also found in 1936, and a tower dating to the Mycenaean period, have been restored and are visible in the basement of the classical structure. Work is currently under way to make this ancient sanctuary accessible to the public.

Arrephorion

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Against the Acropolis’ north fortification wall sits a small, square building that Wilhelm Dörpfeld identified in the 1920s as the Arrephorion. (Dörpfeld was the German archaeologist and architect who pioneered the techniques of stratigraphic archaeology and was Heinrich Schliemann’s successor at Troy.) The Arrephorion was the home of the Arrephoroi, two aristocratic girls between the ages of 7 and 11, who were chosen each year to serve in the cult of the goddess Athena. During the festival of the Arrephoria, celebrated at night in mid-summer, the girls enacted a secret ritual in which they carried chests above their heads — the contents were and still remain a mystery — and descended the Acropolis, likely by means of a stairway concealed inside the north wall. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

While it is known that the Arrephorion, constructed in the fifth century B.C., once had a square hall and four-column colonnade, as well as a rectangular courtyard, all that survive are limestone foundation blocks and fragments of marble. Because the limestone is fragile and the marble cannot be used to restore any extant structure, it was decided that, in contrast to the plans for any other monument on the Acropolis, the Arrephorion would be reburied to protect it. The structure was backfilled in 2006 with soil that could easily be removed if necessary, but is also intended to remain in place for at least 120 years with minimal changes resulting from moisture, seismic activity, or pressure applied to it by contact with the circuit walls.

Archaeology at the Acropolis

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Archaeology, and in particular restoration and conservation of buildings and artifacts, is often described as a jigsaw puzzle, and there likely is none more complex than the scattered stone and marble architectural fragments that lie on the Acropolis. Since 1977, the main goal for researchers there has been to photograph, draw, record, and catalogue these fragments in an attempt to associate them with their original structures, and, if possible, to use them for anastylosis. Thus far more than 20,000 worked pieces of stone and marble have been collected, and 10,000 more without worked surfaces have also been recorded. Of these, at least 65 have been attributed to the Propylaia, four to the Erechtheion, 500 to the “Old Temple,” (the sixth-century B.C. temple the Erechtheion replaced), more than 120 to the Parthenon’s predecessors, and 197 to the Parthenon itself — including many pieces of the “lost” central metopes of the south side of the building, which was blown up in 1687.[Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

This material is also helping re-create a part of the Acropolis’ story that is sometimes forgotten. “The classical Acropolis was far more than just the four major fifth-century buildings,” says classical art historian Jeffrey Hurwit. “It was a very crowded place filled with a sanctuary of Artemis, another of Zeus, another of a hero named Pandion, the Chalkotheke [a bronze warehouse], and hundreds of bronze and marble statues dating to various periods that must have clogged or encroached upon paths through the Acropolis.” Although the remains of many of these ancient monuments are so paltry that true restoration is out of the question, they might remain otherwise little known or even completely unknown but for the scattered fragments that remain. “It’s much easier to build a new building,” says Vassiliki Eleftheriou, “than to rebuild an ancient one.” Eleftheriou, an architect by training, is director of the Acropolis Restoration Service, where she oversees what could be considered the most daunting project in the history of archaeological conservation.

Over the millennia the deterioration of these monuments as a result of the passage of time, and the damage to them from myriad other causes including wars, improper or overly intrusive excavations, new construction, earthquakes, previous restoration efforts, the vast number of visitors to the site, and, most recently, the ravages of pollution and acid rain, have been almost incalculable. In 1975, the Greek government began a large-scale, multidisciplinary project to address the declining condition of these structures, as well as of a lesser-known building called the Arrephorion, the defensive walls encircling the Acropolis, and the so-called “scattered members,” the thousands of complete, nearly complete, and fragmentary pieces of stone and marble that lie all over the surface of the Acropolis.

“What began as a project to rescue the monuments from further decay and instability has evolved into a comprehensive effort not only to restore them, but also to re-create their original appearance insofar as possible. When faced with this exceptional task, the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments followed a governing principle that is applied to all their work. Since the project’s inception, teams working on the Acropolis have employed anastylosis, an intervention technique dating to the beginning of the nineteenth century whereby a structure is rebuilt using original materials. New materials are employed only when necessary, must be easily distinguishable from the old, and must be replaceable should better materials or technologies be found. According to Eleftheriou, this has always been one of the greatest challenges. “It’s important to use as much ancient material as we can, but there is a limit to how much we can actually use,” she says. This is especially true when the team confronts previous efforts at anastylosis. “When we work on sections that have been restored before, it’s difficult not to use new materials because previous restorers often put ancient materials in the wrong places and damaged them. So we try to use compatible materials in a compatible way,” she explains.

“The most ubiquitous and catastrophic of these previous efforts were those of the engineer Nikolaos Balanos, who, between 1898 and 1940, supervised an early attempt to restore the Acropolis. Although the techniques he employed, primarily the use of Portland cement mortar, steel reinforcements, and iron clamps, were generally accepted at the time, after only a short while, the materials started to deteriorate and rust, damaging and often cracking the ancient stone.

“After four decades of intensive work by hundreds of experts in archaeology, architecture, marble working, masonry, restoration, conservation, and mechanical, chemical, and structural engineering, much has been accomplished. Already the restoration of two of the major buildings, the Erechtheion and the Temple of Athena Nike, has been completed, as has much of the work on the Propylaia and on large sections of the Parthenon. In the process, the team has acquired new information about these emblematic buildings. “The Acropolis restoration project has added immeasurably to our knowledge of the fifth-century B.C. monuments atop the Acropolis. Not only has it recovered, identified, and repositioned many once-scattered blocks,” says Hurwit, “it has also revealed new features, such as evidence for previously unsuspected windows on the east wall of the Parthenon.”

“Despite the magnitude of the tasks that remain, Eleftheriou takes both heart and inspiration from the work that she and the team of more than 150 do every day, and also from the ancient artisans who created the Acropolis’ monuments. “What I have learned,” she says, “is that the ancient architects and engineers faced the same challenges we still do.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024