Home | Category: Religion / Art and Architecture

ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES

Pergamon Altar Greek temples were constructed to be admired from the outside. Ordinary people were often not allowed to go inside and if they were there usually wasn't much for them to see except for a large statue of the god the temple honored. On the outside statues were placed in niches. In a couple of instances the columns themselves were made into statues of women.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The Greeks worshipped in sanctuaries located, according to the nature of the particular deity, either within the city or in the countryside. A sanctuary was a well-defined sacred space set apart usually by an enclosure wall. This sacred precinct, also known as a temenos, contained the temple with a monumental cult image of the deity, an outdoor altar, statues and votive offerings to the gods, and often features of landscape such as sacred trees or springs. Many temples benefited from their natural surroundings, which helped to express the character of the divinities. For instance, the temple at Sounion dedicated to Poseidon, god of the sea, commands a spectacular view of the water on three sides, and the Parthenon on the rocky Athenian Akropolis celebrates the indomitable might of the goddess Athena. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Selinus Temple in Sicily was one of the largest Greek temples ever built. It is 362 feet long, 164 feet wide and has 48 columns made of 50 ton blocks that were hoisted 60 feet into the air. Because people often gathered outside a Greek temple rather than in interior could be relatively small. Temples usually features freestanding statues on pediments and relief panels carved into the stone that formed friezes around the building.

See Separate Articles: FAMOUS ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES europe.factsanddetails.com ; ACROPOLIS AND TEMPLES IN ANCIENT ATHENS europe.factsanddetails.com PARTHENON: ITS HISTORY, ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURES europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Complete Greek Temples” by Tony Spawforth (2006) Amazon.com;

“Origins of Classical Architecture: Temples, Orders, and Gifts to the Gods in Ancient Greece” by Mark Wilson Jones (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Earth, the Temple, and the Gods: Greek Sacred Architecture” by Vincent Scully (1979 Amazon.com;

“Greek Sanctuaries and Temple Architecture: An Introduction” by Mary Emerson (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Architecture” (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art)

by A. W. Lawrence (1996) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Architecture” Gene Waddell (2017) Amazon.com;

“Orders of Architecture” by R. A. Cordingley (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Optical Corrections of the Doric Temple: Form and Meaning in Greek Sacred Architecture” by Tapio Uolevi Prokkola (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Parthenon” (Wonders of the World)

by Mary Beard Amazon.com;

“The Parthenon: The Height of Greek Civilization” (Wonders of the World Book) by Elizabeth Mann (Author), Yuan Lee (Illustrator) (2025) Amazon.com;

“Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth”

by Walter Burkert and Peter Bing (1972) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“Smoke Signals for the Gods: Ancient Greek Sacrifice from the Archaic Through Roman Periods” by F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion” by Martin. Nilsson (1968) Amazon.com;

Purpose of Ancient Greek Temples

sanctuary of the Asclepios Temple in Butrint, Albania

Ancient Greek temples, unlike churches, were places the gods lived, not houses of worship. They were regarded as the home of cult statues and places where people could pay homage to gods and leave gifts for them. Some were only entered once or twice a year, and then only by the priest of the temple. Temples were built on hills, known as acropolises, apparently to impress outsiders coming to the city.

On the purpose of Greek temples, Mary Beard wrote in The Times of London, “Forget any idea that temples were the centre of astronomically inspired rituals. Forget any idea that priests spent their time checking out the alignments of the stars. We need to think a bit more broadly about what Greek temples were for — and what they were not...They were not centres of ritual. Any ritual in the Greek world took place in the open air. They were not, like modern churches, mosques or synagogues, a place where a congregation gathered for worship...Greek priests were not specially trained religious, or scientific, experts. Many of them, in fact, were ordinary members of the upper class, who took on religious duties as a part-time extra.” [Source: Mary Beard, The Times, November 19, 2009]

Temples had one main purpose only: to house an image of a god or goddess. The Parthenon in Athens, for example, was home for the huge gold and ivory statue of Athena Parthenos (Athena the Virgin), though it also had a back strong-room, where treasure and precious dedications to the goddess were stored.

Ancient Greek Temple Orientation

A study of Greek temples in Sicily by Alun Salt of the University of Leicester found the temples there were oriented towards the rising sun in the east. The issue of the ordination has long been an issue in the study of Ancient Greek. Most Greek temples were oriented toward the east but enough were oriented towards the west, south and north to leave the impression that orientation was not important. In Salt’s study, 40 of the 41 temples he studied were oriented towards the east, the sole exception was a temple thought to be built in honor of the moon goddess.

On the matter of temple orientation Beard wroe, “Archaeologists have puzzled for more than a hundred years about the orientation of Greek temples. Even without any intricate calculations, it is fairly clear that most of them, though not all, were aligned East-West.Interestingly, the new research appears to show that the temples in the Greek colonies of Sicily are more closely aligned in this direction than their counterparts in Greece itself. It’s a nice idea that the colonists were trying to be even more Greek than those Greeks they had left behind. After all, ex-pats throughout the world have almost always been particularly keen on their old native traditions.

So why did the Greeks generally choose to align the statue’s house East-West? My guess is that they liked to place the god at the centre of the natural world, in line with the rhythms of night and day and the rising and setting of the sun. If an inconvenient marsh, or an awkward slope got in the way, they were happy enough to orientate the building in any direction. The famous temple of Bassae, for example, in the wilds of the Peloponnese stands north-south.

\ In a study that aimed to figure out why temples were located where the were by taking into account geology, topography, soil type, vegetation and works by writers like Homer, Plato and Herodotus, University of Oregon professor Gregory Retallack could not find any kind or correlation except that between the god worshipped and the predominate soil type at the temple site. Retallack found fertile, well-structured soils call Xerolis were the dominant soil type at temples for Demeter, the goddess of fertility, and Dionysus, the god of wine. Rocky Orthent and Xerept soil were found at temples for Artemis, the virgin huntress and Apollo while Calcid soils, found in coastal areas too dry for agriculture, were found at temples for the maritime deities Poseidon and Aphrodite, the goddess of love.

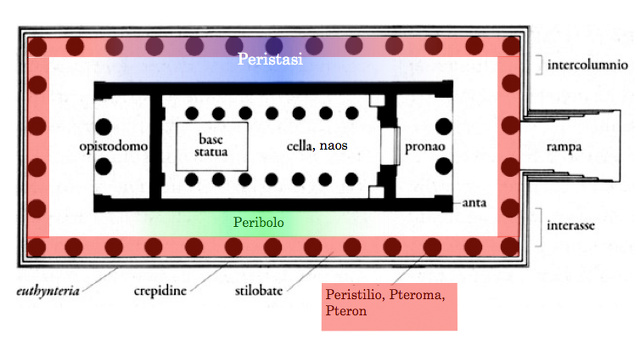

Greek temple plans

History of Ancient Greek Temple Architecture

From early times, the open air altar played an important role in worship. The outdoor aspect was a practical consideration. Sacrificing 100 head of oxen, as happened on festive occasions such as at the Olympic Games, with its inevitable blood and smoke, was an activity best carried out in the open air. But, influenced by the East- particularly, Egypt- temples began to be seen as appropriate structures to house the image of a deity. That usage dictated a level of quality befitting a divine being. Accordingly, the Greeks looked to their predecessors and to their neighbours for ideas on suitable designs for a temple. From their Mycenaean ancestors they took the idea of an architectural footprint based on the rectangular megaron or “great hall”- a room with a frontal porch supported by columns. From the Egyptians they borrowed the concept of monumentality and a range of design elements and ornaments such as fluted columns, palmettes, spirals, rosettes, lotus plant imagery, etc. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

“The first Greek temples were a far cry from a classical masterpiece such as the Parthenon. During the Bronze Age it seems that no temples were built and there is uncertainty as to when they began to be built. It happened during the Dark Age but surviving examples, according to A.W. Lawrence are “few in number and of deplorable quality.” The construction materials were mud brick for the walls with high-pitched roofs made of timber. Greek builders were not satisfied for long with this model and they gradually made their way to stone construction. |

“During the 7th century the Greek “Orders of Architecture” began its evolution. Few people today are not familiar with the notion that there are Doric, Ionic and Corinthian styles. Many can even pick out the different styles in modern examples in their cities for these became widely admired and copied throughout the world...The Parthenon is considered to be the greatest of the Doric temples, the ultimate achievement of architectural perfection in this style. |

“All three styles are built upon a single construction system — the post and lintel- where a horizontal block of stone (the lintel) is laid across two supports (posts or columns). It was a simple system which imposed some limitations on the architects but it assured an appropriate result. An inspired architect might produce a Parthenon but a less gifted individual would at least produce a temple adequate for religious worship. Instead of seeking innovation in other systems and styles, Greek architects sought refinement and perfection in the system that they had chosen. They laid down a framework of rules which spelled out how to address composition and proportion. All of the elements and components had a specified form and function. Tey working within that formula Greek architects were able to produce a range of distinctive temples including some that made the List of Wonders of the ancient world. |

Temple features

Ancient Greek Temple Construction

Ancient Greek temples were designed and constructed by craftsmen and decisions about column size and their location, it appears, were made when the building was being erected. According to Boorstin "scholars have not found a single architectural drawing." Most temples had a similar design and really the only creative work done by the architects was the artwork on the friezes and lintels. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,"]

To construct a temple, Greek builders used ropes, pulleys and wooden cranes, as high as 80 feet tall, and sometimes used 25-foot-tall teamons, statues of a giant used as a support. Rough limestone columns were lifted and placed and then fluted by a stone cutter.

“According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Although the ancient Greeks erected buildings of many types, the Greek temple best exemplifies the aims and methods of Greek architecture. The temple typically incorporated an oblong plan, and one or more rows of columns surrounding all four sides. The vertical structure of the temple conformed to an order, a fixed arrangement of forms unified by principles of symmetry and harmony. There was usually a pronaos (front porch) and an opisthodomos (back porch). The upper elements of the temple were usually made of mudbrick and timber, and the platform of the building was of cut masonry. Columns were carved of local stone, usually limestone or tufa; in much earlier temples, columns would have been made of wood. Marble was used in many temples, such as the Parthenon in Athens, which is decorated with Pentelic marble and marble from the Cycladic island of Paros. The interior of the Greek temple characteristically consisted of a cella, the inner shrine in which stood the cult statue, and sometimes one or two antechambers, in which were stored the treasury with votive offerings. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The quarrying and transport of marble and limestone were costly and labor-intensive, and often constituted the primary cost of erecting a temple. For example, the wealth Athens accumulated after the Persian Wars enabled Perikles to embark on his extensive building program, which included the Parthenon (447–432 B.C.) and other monuments on the Athenian Akropolis. Typically, a Greek civic or religious body engaged the architect, who participated in every aspect of construction. He usually chose the stone, oversaw its extraction, and supervised the craftsmen who roughly shaped each piece in the quarry. At the building site, expert carvers gave the blocks their final form, and workmen hoisted each one into place. The tight fit of the stones was enough to hold them in place without the use of mortar; metal clamps embedded in the stone reinforced the structure against earthquakes. A variety of skilled labor collaborated in the raising of a temple. Workmen were hired to construct the wooden scaffolding needed for hoisting stone blocks and sculpture, and to make the ceramic tiles for the roofs. Metalworkers were employed to make the metal fittings used for reinforcing the stone blocks and to fashion the necessary bronze accoutrements for sculpted scenes on the frieze, metopes and pediments. Sculptors from the Greek mainland and abroad carved freestanding and relief sculpture for the eaves of the temple building. Painters were engaged to decorate sculptural and architectural elements with painted details.” \^/

five orders of architecture

Altars and Worship at an Ancient Greek Temple

The cult statue of an ancient Greek temple was often oriented towards an altar, placed axially in front of the temple. To preserve this connection, the single row of columns often found along the central axis of the temple in early temples was replaced by two separate rows towards the sides. An amphora decorated with a religious scene shows a common type of altar. It is shaped rather like a pedestal with an architectural moulding and “horns” on either side. A miniature terracotta shrine from Cyprus, made for household use, gives us an idea of the shape of the larger ones which held a statue at crossroads and street corners. Incense, a frequent accompaniment of worship, was burned in a covered vessel, often provided with a high stand, such as the incense burner painted on a small oinochoë; or a little altar was used for the purpose. An example from Cyprus, which still shows traces of fire. A marble lamp was made to be set in a support, probably a bronze tripod, and was filled with oil in which a wick floated. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Images on reliefs show little tables with articles of food near an altar. We see a ham, a whole boar, some cakes, fruit, and various dishes of food. Near these tables is a little tray with several cakes represented in relief upon it, a substitute for the cakes which were placed on tables in the temples.The group of vases connected by a ring was used for offering small portions of liquid, probably oil, wine, honey, or milk. Gratitude for the cure of disease was often exhibited by dedicating a representation of the affected part. On the top shelf at the left are terracotta plaques showing eyes, eyes and mouth, and an ear. The manufacture and sale of such objects formed an industry in ancient times, and the records of the temple of Asklepios at Athens which are still preserved contain long lists of them.

The ceremonies and sacrifices in temples were few compared to the frequent occasions for private and family worship. An interesting terracotta relief represents two warriors clasping hands. Perhaps it may be regarded as a votive offering made to commemorate a treaty or an alliance, either of which with the Greeks and also the Romans was an agreement made in the sight of the gods and accompanied by sacrifices. Readers of the Anabasis will remember the treaty made by the Greeks and the Persians after Cyrus’s death (II, ii, 8, 9), when the sword-blades and spear-heads were dipped in the blood of the victims caught in a shield, and the leaders on both sides gave their right hands as a pledge of fidelity.

2,700-Year-Old Temple with Altar “Overflowing” Gold, Jewels and Offerings

In January 2024, archaeologists announced they had found a temple adjacent to a sanctuary dedicated to the Greek goddess Artemis on the Greek island of Evia with a horseshoe-shaped altar “overflowing with offerings.” Constructed of bricks, the temple is 30 meters (100 feet) long and is located next to the Temple of Amarysia Artemis, which researchers found in 2017, according to a statement from Greece's Ministry of Culture. [Source Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, January 12, 2024]

During excavations in 2023, archaeologists found the second temple. "One of the peculiarities of this temple is the significant number of structures found inside it," the researchers. Live Science reported: Those structures included several hearths located in the temple's nave, including the ash-caked altar stacked with offerings such as pottery; vases; Corinthian alabaster, or the carved mineral gypsum; gold and silver jewelry studded with coral and amber; amulets; and bronze and iron fittings. The altar also contained several pieces of charred bone.

Some of the pottery pieces predate the newfound temple and were fired during the late eighth century B.C., leading researchers to suspect that the altar may have once resided outside the temple and was later moved indoors. In the sixth century B.C., brick partitions were placed at the sanctuary's heart for added support, leading researchers to think that the temple was "partially destroyed" by a fire, according to the statement. Beneath the temple, archaeologists found several dry stone walls from a different building that once stood at the site, along with several bronze figurines shaped like bulls and a ram. They also unearthed remnants of buildings from the eighth and ninth centuries B.C. next to the first temple, as well as a fortification system dating to the more recent early Copper Age, or roughly 4000 to 3500 B.C.

Activities at Ancient Greek Temples

Strabo wrote in “Geographia,” (c. 20 A.D.) about Greece around 550 B.C: “And the temple of Aphrodite in Corinth was so rich that it owned more than a thousand temple slaves — prostitutes — whom both free men and women had dedicated to the goddess. And therefore it was also on account of these temple-prostitutes that the city was crowded with people and grew rich; for instance, the ship captains freely squandered their money, and hence the proverb, "Not for every man is the voyage to Corinth."

Philo Judaeus wrote in “De Providentia” (c. A.D. 20): “At Ascalon, I observed an enormous population of doves in the city-squares and in every house. When I asked the explanation, I was told they belonged to the great temple of Ascalon — where one can also see wild animals of every description, and it was forbidden by the gods to catch them.” [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed. “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 268, 289]

Plutarch wrote in “Moralia” (c. A.D. 110): “It's not the abundance of wine or the roasting of meat that makes the joy of sharing a table in a temple, but the good hope and belief that the god is present in his kindness and graciously accepts what is offered. [Source: Plutarch, Moralia, translated by Philemon Holland, (London: J.M. Dent, 1912).

1 Corinthians 8 (c. A.D. 56) from the New Testament reads: “So about the eating of meat sacrificed to idols, we know that "there is no idol in the world," and that "there is no God but one." ...But not all have this knowledge. There are some who have been so used to idolatry up until now that, when they eat meat sacrificed to idols, their conscience, which is weak, is defiled.....If someone sees you, with your knowledge, reclining at table in the temple of an idol, may not his conscience, too, weak as it is, be "built up" to eat the meat sacrificed to idols?

Priests and Priestesses at Ancient Greek Temples

There was no formal priesthood in Ancient Greece. There were leaders of local cults and priests who worked at specific temples, who were paid by donations to the temples. Many religious rituals in ancient Greece could be performed by individuals either at a temple or elsewhere without a priest. The priest existed, in the first place, for the sake of the god, and only in the second in order to facilitate the intercourse between god and man. The gods desired worship and sacrifice, and, as it could not be left to chance whether some one person would supply these, since there must be no interruption to the worship, it was necessary to have a class of men whose work in life was the performance of these duties towards the divinity. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

recreation of an Artemis Temple ritual

Herodotos wrote in “Histories” (c. 430 B.C.): “And so the word which came to Cleomenes [King of Sparta] received its fulfillment. For when he first went up into the citadel, meaning to seize it, just as he was entering the sanctuary of the goddess, in order to question her, the priestess arose from her throne, before he had passed the doors, and said, "Stranger from Sparta, depart hence, and presume not to enter the holy place---it is not lawful for a Dorian to set foot there." But he answered, "Woman, I am not a Dorian, but an Achaian." Slighting this warning, Cleomenes made his attempt, and so he was forced to retire, together with his Spartans. [Source: Herodotus, “Histories”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862)

An Inscription from Miletus dated to 275 B.C. reads: “Whenever the priestess performs the holy rites on behalf of the city, it is not permitted for anyone to throw pieces of raw meat anywhere, before the priestess has thrown them on behalf of the city, nor is it permitted for anyone to assemble a band of maenads before the public thiasos has been assembled. And whenever a woman wishes to perform an initiation for Dionysos Bacchios in the city, in the countryside, or on the islands, she must pay a piece of gold to the priestess at each biennial celebration.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK RELIGIOUS PRACTICES: PRIESTS, RITUALS AND PRAYERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Temple Prostitutes in Ancient Greece

Two categories of prostitutes in ancient Greek were specifically related to sacred or temple prostitution are: 1) hetaires, also known as courtesans, typically more educated women that served within temples; and 2) as hierodoules, slave women or female priests who worked within temples and served the sexual requests of visitors to the temple. While there may not be a direct connection between temples and prostitution, many prostitutes and courtesans worshipped Aphrodite, the goddess of love, and would use their earnings to pay for dedications and ritualistic celebrations in honour of the goddess. Some prostitutes also viewed the action of sexual service and sexual pleasure as an act of devotion to the goddess of love, worshipping Aphrodite through an act rather than a physical dedication. [Source Wikipedia]

Sacred prostitution within the Temples of Aphrodite in the city of Corinth was well-known. Strabo wrote in “Geographia,” (c. 20 A.D.) about Greece around 550 B.C: “The temple of Aphrodite in Corinth was so rich that it owned more than a thousand temple slaves — prostitutes — whom both free men and women had dedicated to the goddess. And therefore it was also on account of these temple-prostitutes that the city was crowded with people and grew rich; for instance, the ship captains freely squandered their money, and hence the proverb, "Not for every man is the voyage to Corinth."” In the same work, Strabo compares Corinth to the city of Comana, confirming the belief that temple prostitution was a notable characteristic of Corinth.

Prostitutes performed sacred functions within the temple of Aphrodite. They would often burn incense in honor of Aphrodite. Chameleon of Heracleia recorded in his book, On Pindar, that whenever the city of Corinth prayed to Aphrodite in manners of great importance, many prostitutes were invited to participate in the prayers and petitions.

The girls involved in temple prostitution were typically slaves owned by the temple. In the temple of Apollo at Bulla Regia, a woman was found buried with an inscription reading: "Adulteress. Prostitute. Seize [me], because I fled from Bulla Regia." It has been speculated she might have been a woman forced into sacred prostitution as a punishment for adultery.

However, some of the girls were gifted to the temple from other members of society in return for success in particular endeavors. One example that shows the gifting of girls to the temple is the poem of Athenaeus, which explores an athlete Xenophon’s actions of gifting a group of courtesans to Aphrodite as a thanks-offering for his victory in a competition.

Rituals in the Temple of Athena in Athens

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): ““Both the city and the whole of the land are alike sacred to Athena; for even those who in their parishes have an established worship of other gods nevertheless hold Athena in honor. But the most holy symbol, that was so considered by all many years before the unification of the parishes, is the image of Athena which is on what is now called the Acropolis, but in early days the Polis (City). A legend concerning it says that it fell from heaven; whether this is true or not I shall not discuss. A golden lamp for the goddess was made by Callimachus. Having filled the lamp with oil, they wait until the same day next year, and the oil is sufficient for the lamp during the interval, although it is alight both day and night. The wick in it is of Carpasian flax, the only kind of flax which is fire-proof, and a bronze palm above the lamp reaches to the roof and draws off the smoke. The Callimachus who made the lamp, although not of the first rank of artists, was yet of unparalleled cleverness, so that he was the first to drill holes through stones, and gave himself the title of Refiner of Art, or perhaps others gave the title and he adopted it as his. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“In the temple of Athena Polias (Of the City) is a wooden Hermes, said to have been dedicated by Cecrops, but not visible because of myrtle boughs. The votive offerings worth noting are, of the old ones, a folding chair made by Daedalus, Persian spoils, namely the breastplate of Masistius, who commanded the cavalry at Plataea1, and a scimitar said to have belonged to Mardonius. Now Masistius I know was killed by the Athenian cavalry. But Mardonius was opposed by the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) and was killed by a Spartan; so the Athenians could not have taken the scimitar to begin with, and furthermore the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) would scarcely have suffered them to carry it off. About the olive they have nothing to say except that it was testimony the goddess produced when she contended for their land. Legend also says that when the Persians fired Athens the olive was burnt down, but on the very day it was burnt it grew again to the height of two cubits.

“Adjoining the temple of Athena is the temple of Pandrosus, the only one of the sisters to be faithful to the trust. I was much amazed at something which is not generally known, and so I will describe the circumstances. Two maidens dwell not far from the temple of Athena Polias, called by the Athenians Bearers of the Sacred Offerings. For a time they live with the goddess, but when the festival comes round they perform at night the following rites. Having placed on their heads what the priestess of Athena gives them to carry — neither she who gives nor they who carry have any knowledge what it is — the maidens descend by the natural underground passage that goes across the adjacent precincts, within the city, of Aphrodite in the Gardens. They leave down below what they carry and receive something else which they bring back covered up. These maidens they henceforth let go free, and take up to the Acropolis others in their place. By the temple of Athena is .... an old woman about a cubit high, the inscription calling her a handmaid of Lysimache, and large bronze figures of men facing each other for a fight, one of whom they call Erechtheus, the other Eumolpus; and yet those Athenians who are acquainted with antiquity must surely know that this victim of Erechtheus was Immaradus, the son of Eumolpus. On the pedestal are also statues of Theaenetus, who was seer to Tolmides, and of Tolmides himself, who when in command of the Athenian fleet inflicted severe damage upon the enemy, especially upon the Peloponnesians.”

Sacred Groves

statuette of a priestess, AD 250

Psudeo -Lucian wrote in “Am” (c. A.D. 85): “Around the sanctuary of Aphrodite at Knidos was an orchard, and under the most deeply-shadowy trees were cheerful picnic places for those who wanted to provide a banquet there; and some of the more well-bred used these, sparingly, but the whole city crowd held festival there, in truly Aphrodisiac fashion. And at Formiae, a benefactor staged each year a ceremony for Jupiter, at which he would distribute 20 sesterces to each of the city senators dining publicly in the grove.

In the sacred grove and temples of Asclepius at Epidaurus in the northeastern Peloponnese, Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book II: Cornith: “The sacred grove of Asclepius is surrounded on all sides by boundary marks. No death or birth takes place within the enclosure the same custom prevails also in the island of Delos. All the offerings, whether the offerer be one of the Epidaurians themselves or a stranger, are entirely consumed within the bounds. At Titane too, I know, there is the same rule. The image of Asclepius is, in size, half as big as the Olympian Zeus at Athens, and is made of ivory and gold. An inscription tells us that the artist was Thrasymedes, a Parian, son of Arignotus. The god is sitting on a seat grasping a staff; the other hand he is holding above the head of the serpent; there is also a figure of a dog lying by his side. On the seat are wrought in relief the exploits of Argive heroes, that of Bellerophontes against the Chimaera, and Perseus, who has cut off the head of Medusa. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“Over against the temple is the place where the suppliants of the god sleep. Near has been built a circular building of white marble, called Tholos (Round House), which is worth seeing. In it is a picture by Pausias1 representing Love, who has cast aside his bow and arrows, and is carrying instead of them a lyre that he has taken up. Here there is also another work of Pausias, Drunkenness drinking out of a crystal cup. You can see even in the painting a crystal cup and a woman's face through it. Within the enclosure stood slabs; in my time six remained, but of old there were more. On them are inscribed the names of both the men and the women who have been healed by Asclepius, the disease also from which each suffered, and the means of cure. The dialect is Doric. Apart from the others is an old slab, which declares that Hippolytus dedicated twenty horses to the god. The Aricians tell a tale that agrees with the inscription on this slab, that when Hippolytus was killed, owing to the curses of Theseus, Asclepius raised him from the dead. On coming to life again he refused to forgive his father rejecting his prayers, he went to the Aricians in Italy. There he became king and devoted a precinct to Artemis, where down to my time the prize for the victor in single combat was the priesthood of the goddess. The contest was open to no freeman, but only to slaves who had run away from their masters.

“The Epidaurians have a theater within the sanctuary, in my opinion very well worth seeing. For while the Roman theaters are far superior to those anywhere else in their splendor, and the Arcadian theater at Megalopolis is unequalled for size, what architect could seriously rival Polycleitus in symmetry and beauty? For it was Polycleitus1 who built both this theater and the circular building. Within the grove are a temple of Artemis, an image of Epione, a sanctuary of Aphrodite and Themis, a race-course consisting, like most Greek race-courses, of a bank of earth, and a fountain worth seeing for its roof and general splendour.

sacred springs of Dion, near Mt Olympus

A Roman senator, Antoninus, made in our own day a bath of Asclepius and a sanctuary of the gods they call Bountiful.1 He made also a temple to Health, Asclepius, and Apollo, the last two surnamed Egyptian. He moreover restored the portico that was named the Portico of Cotys, which, as the brick of which it was made had been unburnt, had fallen into utter ruin after it had lost its roof. As the Epidaurians about the sanctuary were in great distress, because their women had no shelter in which to be delivered and the sick breathed their last in the open, he provided a dwelling, so that these grievances also were redressed. Here at last was a place in which without sin a human being could die and a woman be delivered. Above the grove are the Nipple and another mountain called Cynortium; on the latter is a sanctuary of Maleatian Apollo. The sanctuary itself is an ancient one, but among the things Antoninus made for the Epidaurians are various appurtenances for the sanctuary of the Maleatian, including a reservoir into which the rain-water collects for their use.

“The serpents, including a peculiar kind of a yellowish color, are considered sacred to Asclepius, and are tame with men. These are peculiar to Epidauria, and I have noticed that other lands have their peculiar animals. For in Libya only are to be found land crocodiles at least two cubits long; from India alone are brought, among other creatures, parrots. But the big snakes that grow to more than thirty cubits, such as are found in India and in Libya, are said by the Epidaurians not to be serpents, but some other kind of creature. As you go up to Mount Coryphum you see by the road an olive tree called Twisted. It was Heracles who gave it this shape by bending it round with his hand, but I cannot say whether he set it to be a boundary mark against the Asinaeans in Argolis, since in no land, which has been depopulated, is it easy to discover the truth about the boundaries. On the Top of the mountain there is a sanctuary of Artemis Coryphaea (of the Peak), of which Telesilla made mention in an ode.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024