Home | Category: Art and Architecture

PARTHENON

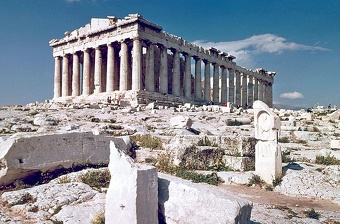

The Parthenon (on the top of the Acropolis in Athens) is is one of the world's most famous monuments and one of the best known architectural symbols of any civilization. Dedicated to Athena Parthhenos, the Virgin, patron of Athens, and built in only nine years between 447-438 B.C., this ancient Greek temple was designed as a replacement for a temple destroyed by the Persians in 480 B.C. and was originally painted with bright colors. Made of Pentelic marble, it was designed by the architect Iktinos to hold the monumental gold and ivory (chryselephantine) statue of Athena designed by the sculptor-architect Pheidias. The name, "Parthenon", refers to the room where the virgin goddess Athena (Athena Parthenos), had her statue. The Parthenon was the first temple built on the Acropolis after a Persian invasion that nearly destroyed Athens, goddess of Athens.

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: This massive and highly refined temple, constructed with at least 70,000 unique pieces of marble quarried on Mount Pentele almost 32 kilometers (20 miles) from Athens, was designed by the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates under the supervision of Pheidias, the greatest sculptor of his day. Its sculptural program, completed six years after the building, depicted, among other subjects, mythological scenes, allusions to the Athenians’ victory over the Persians, episodes from Athena’s life — her birth, her contest with Poseidon for Athens — and the Panathenaia, the yearly festival held in her honor. Inside the temple stood a nine-meter (30-foot) -tall ivory and gold statue, now completely lost, of the goddess depicted as a warrior and protectress of her city. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

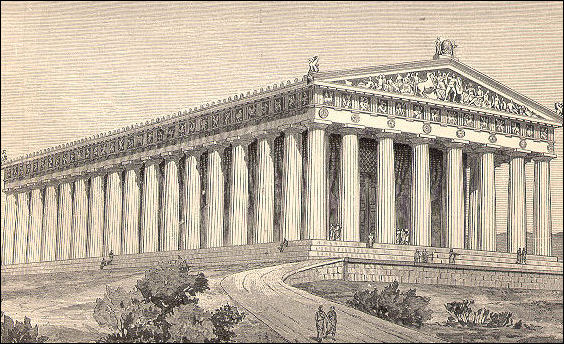

The Parthenon is 70 meters (228 feet) long, 31 meters (101 feet) wide and 18 meters (60 feet) high. It has 17 outer columns on the north and south sides and eight columns at each end. It covers an area about half the size of a football field. The 46 outer columns are 11 meters (36 feet) high The main structure is built of limestone and marble. A 170 meter (558 foot) frieze once wrapped around the top of the exterior wall. The roof is missing and there are several stories as to how this happened.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES, SANCTUARIES AND SACRED PLACES europe.factsanddetails.com ; FAMOUS ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Parthenon” (Wonders of the World)

by Mary Beard Amazon.com;

“The Parthenon: The Height of Greek Civilization” (Wonders of the World Book) by Elizabeth Mann (Author), Yuan Lee (Illustrator) (2025) Amazon.com;

“Parthenon Sculptures” by Ian Jenkins Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“The Complete Greek Temples” by Tony Spawforth (2006) Amazon.com;

“Origins of Classical Architecture: Temples, Orders, and Gifts to the Gods in Ancient Greece” by Mark Wilson Jones (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Earth, the Temple, and the Gods: Greek Sacred Architecture” by Vincent Scully (1979 Amazon.com;

“Greek Sanctuaries and Temple Architecture: An Introduction” by Mary Emerson (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Optical Corrections of the Doric Temple: Form and Meaning in Greek Sacred Architecture” by Tapio Uolevi Prokkola (2011) Amazon.com;

“Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth”

by Walter Burkert and Peter Bing (1972) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“Smoke Signals for the Gods: Ancient Greek Sacrifice from the Archaic Through Roman Periods” by F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion” by Martin. Nilsson (1968) Amazon.com;

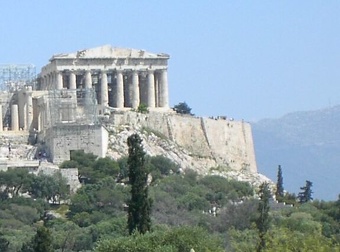

Acropolis

The Acropolis is the name of the huge rock in Ayhens on which the Parthenon stands. Anchored by huge walls and surrounded by a forest of unassembled ruins the Acropolis rises out of Athens like a miniature Mt. Olympus. An important secular and sacred site, it was home to he city's treasury as well as temples for religious rites and sacrifices.

Caves near a natural spring on the steep north side of the Acropolis have been inhabited since Neolithic times and the fortress-like walls around the Acropolis were built by the Mycenaeans to protect a palace they had erected at the top. This was superseded by a Greek temple dedicated to Poseidon and Athena that was destroyed in 480 B.C. when the entire city of Athens was burned to ground by the Persian army of Xeres. In the Golden Age of Greece the caves contained a shrine to Pan and other Gods.

From the Acropolis , it is easy to see why this abrupt steep-sided rock was chosen as the first citadel of ancient Athens: it is a superb natural defensive site. Once fortified, it was virtually impregnable, although defenders were hampered by the lack of water on the Acropolis . Still, the Acropolis was a fitting home for the virgin warrior goddess, Athena. [Source: Internet Archive, from vacation.net.gr]

Many of the temples built on the Acropolis were shrines to Athena, as is the Parthenon which remains today. Its predecessor, the massive Hekatompedon of Peisistratus, was located slightly to the north of the Parthenon, beside the present Erechtheion. The Hekatompedon (also known as the "Old Temple of Athena"), was burnt in the Persian sack of Athens in 480 B.C. Its foundations remain on the Acropolis , and are the only remnants of the buildings which were on the Acropolis before the Persians sacked the city. Parts of the temple were built into the north wall of the Acropolis , where some of the massive column drums may still be seen.

However grand the buildings with which Peisistratos adorned the Acropolis , they did not survive the Persian onslaught. Fortunately, many of the buildings erected by Pericles a half century later have survived, and it is the Periclean Acropolis which we visit today. Of these buildings, the most famous is the Parthenon (447-32 B.C.), flanked by the temple of Athena Nike (427-24 B.C.) and the Erechtheion (421-06 B.C.). In addition, Pericles was responsible for the building of the Propylaia (437-32 B.C.), the monumental entrance way to the Acropolis .

“The Acropolis of Athens is the most striking and complete ancient Greek monumental complex still existing in our times. It is situated on a hill of average height (156 meters, 510 feet) that rises in the basin of Athens. Its overall dimensions are approximately 170 by 350 meters (560 by 1150 feet). The hill is rocky and steep on all sides except for the western side, and has an extensive, nearly flat top. Strong fortification walls have surrounded the summit of the Acropolis for more than 3,300 years. The first fortification wall was built during the 13th century B.C. and surrounded the residence of the local Mycenaean ruler. In the 8th century B.C. the Acropolis gradually acquired a religious character with the establishment of the cult of Athena, the city’s patron goddess. The sanctuary reached its peak in the archaic period (mid-6th century to early 5th century B.C.). In the 5th century B.C. the Athenians, empowered from their victory over the Persians, carried out an ambitious building programme under the leadership of the great statesman Perikles, comprising a large number of monuments including the Parthenon, the Erechtheion, the Propylaia and the temple of Athena Nike.

See Separate Articles: ACROPOLIS AND TEMPLES IN ANCIENT ATHENS europe.factsanddetails.com

Acropolis reconstructed

History of the Parthenon

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine:“In 479 B.C. the monuments of the Acropolis lay in ruins, destroyed by the Persians who had sacked Athens in their struggle for control of Greece. Only a few decades later, the conflict with the Persians was over, and, in 448 B.C., the decision was made, initiated by the general and statesman Pericles, to rebuild the temples as a way to celebrate that victory and mark a new era of Greek power, ushering in what has been called the Golden Age. The first to be rebuilt, and the centerpiece of the project, was the Parthenon. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

Built between 447 and 438 B.C., the Parthenon was the centerpiece of a building campaign on the Acropolis launched in the mid 5th century B.C. when Athens was rich from tribute money paid to it by 150 to 200 city states. It was commissioned by Pericles — who said, "We have forced every sea and land to be the highway of daring, and everywhere...have left imperishable monuments behind us” — and supported by the citizens of Athens who voted in favor of funding it.

One reason why Greece was so vulnerable to Spartan attack during the Peloponnesian War was that the money that would have gone to pay an army was used instead to pay for the building of the Parthenon. Pericles was accused by Thucydides of adorning the city "like a harlot with precious stones, statues and temples costing a thousand talents." Many of the pieces of temple destroyed by the Persians was used as fill and centuries later priceless pieces of Greek statuary was pulled from the rubble.

The Parthenon served as both a temple and a treasury for the Delian League (an alliance of city-states that paid tribute to Athens). A heavily-guarded iron cage kept the treasury safe. The cost of the Parthenon without the Athena statue was more than the entire revenue of the city for one year. Money from the common treasury from all the city states on the Delos League was also used without the consent of the other states.

Athenian citizens used to line the promenade of the Stoa of Attalos in the Agora to watch the Panatheenaic procession in which a huge dress was hauled up to the Acropolis as an offering to Athena. Near the Parthenon was a 30-foot-high bronze statue of Athena Promachos, the Warrior, whose metal glistened so brightly it was said it could be seen by ships approaching Athens.

One of the main architects of the Parthenon, Phidias, was thrown in jail for creating "a likeness of himself as a bald old man holding up a great stone with both hands, and had put in a very fine representation of Pericles fighting an Amazon." Pericles was the statesman who ruled Athens the time the Parthenon was being built and his offense was "impiety" for placing himself in the same arena as the gods. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Pericles and the Parthenon

Pericles

The Parthenon was built in the 15 year period between 447-432 B.C. under the stewardship of great Athenian statesman Perciles. To build a temple of this size (101 x 228 ft.; 30.9m x 69.5m) in that short a timeframe was considered amazing but what was even more amazing was the quality of construction and finishing, which was superb. The leading politician of the day and the man behind the construction project was Pericles. According to Plutarch, the great Greek biographer writing centuries after the building was completed; one of the main reasons for the construction of the Parthenon and the other temples which surrounded it was the need to deal with growing unemployment. By embarking on a major public works program for the acropolis (the towering hill in Athens where the Parthenon and other temples dedicated to the gods were located) Pericles hoped to provide jobs for ordinary Athenians- carpenters, stonemasons, ivory-workers, painters, enamellers, pattern-makers, blacksmiths, rope-makers, weavers, engravers, merchants, coppersmiths, potters, shoemakers, tanners, laborers, etc. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

“At the same time and more importantly, he envisioned the Parthenon as an architectural masterpiece that would make a statement to the world about the superiority of Athenian values, their system of governance and their way of life. Because of this, only the best building materials were good enough- the finest stone, bronze, gold, ivory, ebony, cypress-wood- and the best artists and craftsmen. It was to be a building for the ages. In a funeral oration delivered in 430 B.C. Pericles expressed his pride in the city of Athens and there seems no doubt he was thinking of the Parthenon when he noted that “Mighty indeed are the marks and monuments we have left. Men of the future will wonder at us, as all men do today.”

The new construction project was not welcomed by everyone. There were some who were outraged that so much money was being spent on the construction “gilding and beautifying our city as if it were some vain woman decking herself out with costly stones and thousand talent temples”. Many were also upset that the monies to build the Parthenon were being supplied, reluctantly, by Athenian allies who had originally handed over this money for use in any future conflict against the Persians. Pericles argued that as long as the Athenians honored their commitment to defend these allies against Persian aggression, then the allies had nothing to complain about. And the majority of people supported Pericles. In fact his most vocal opponent was ostracized (banished for ten years) by a popular vote leaving the way clear to proceed with construction. |

“The Parthenon building program was carried out under the general direction of Pericles himself. He chose three men at the top of their professions to collaborate on the design and execution of the project. Although we don't know everything that each did, it seems that Ictinuswas the chief architect, Callicratus acted as the project contractor and technical coordinator while Phideas was responsible for overseeing and integrating all artistic elements. He also personally created the enormous gold and ivory sculpture of the city goddess and produced some of the various sculptural groupings while supervising the production efforts of a small army of artists and craftsmen. Phideas was recognized at the time as being the greatest sculptor of his era but is acknowledged now as the greatest Greek sculptor of all time. The collaboration of the threesome was an enduring success. |

“The dream of Pericles, that the Parthenon would be an imperishable symbol of the greatness of Athens and of the inevitable triumph of civilization over the forces of barbarism, was short-lived. The last of the sculptural ornaments was completed in 432 B.C. but only three years later Pericles and many of his fellow citizens succumbed to a horrific plague that devastated Athens.” |

Architecture of the Parthenon

Designed by the Greek architects Ictinus and Callicrates, the Parthenon is impressive not so much for it its overall size; but the sense of spaciousness and height created by architecture that is otherwise massive and foreboding. Arches weren't perfected until the Roman times and Greek architecture depended on large numbers of thick columns to support a structure. The Doric columns in the Parthenon are indeed monolithic but the are spaced in such a way that the building doesn't seem as heavy as they could have been.

The columns are slightly curved and they bulge at the top to create the optical illusion of straight and perfect symmetry. Straight columns look as if they are thin, and thus weak. The fact they slant slightly inward and the floor is slight bowed (about 10 centimeters on the sides and six centimeters on the front and back with a slight bulge in the middle) not only helped to relieve some of the stress of the roof but it also gave the structure the illusion that it was reaching towards a pinnacle. The sense of spaciousness is heightened ever more by the fact there is no roof and many of the columns have fallen down (yuk, yuk, yuk).

The Parthenon has an exterior colonnade of eight Doric columns at each end, and seventeen Doric columns along each side. Each of these columns bulges slightly in the middle, a device which pre vents the massive columns from seeing lifeless and overly regular. In addition, this swelling (known in Creek as "entasis") corrected the optical illusion whereby perfectly straight columns appear to be slightly concave. [Source: Internet Archive, from vacation.net.gr]

The Parthenon is a Doric temple, which artfully incorporated selected Ionic features to produce a building that many, including some of the world's top architects, have called perfect. The Doric style uses thicker columns and has a more massive appearance (sometimes called masculine) than the Ionic (feminine) style. This may have been a politically inspired choice by Pericles, symbolically uniting Greeks of Dorian and Ionian backgrounds in one transcendent building. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

“The Parthenon is classified as a peripteral temple, that is, the perimeter of the structure is defined by columns, in this case by eight on the narrow ends and seventeen on the long sides, for a total of 46 columns. Sitting inside the exterior columns is a raised stone platform. This supports the floor-to-ceiling walls of a shoebox-like room called the Cella or Naos. In traditional temples this is a single room but in the case of the Parthenon, the Cella has been divided into two rooms. In the larger one, a huge standing statue of Athena was located, resting on a support slab. In front of the statute…a reflecting pool. In the smaller room, with the four interior columns, was kept the state treasury, including cash gifts to the deity. The collection of interior columns was necessary to support the roof that, like the rest of the building, was made of marble.” |

Hekatompedon: Part of the Parthenon with the Statue of Athena

replica of Phidias's giant Athena statue in the Parthenon

Within the temple itself were two chambers, one in which the statue of Athena Parthenos stood, and one which housed the temple treasury. Visitors to the Parthenon today, disappointed not to be allowed inside, should take some comfort from the fact that most Athenians in antiquity never were permitted inside the temple. Only priests ever entered the treasury, and the statue itself was viewed only rarely. One of those who saw the statue was Pausanias, who describe the Athena as standing "upright in an ankle length tunic with a head of Medusa carved in ivory on her breast. She has a Victory about eight feet high, and a spear in her hand and a shield at her feet, and a snake beside the shield; this snake might be Erichthonios."

The portion of the Cella where the magnificent statue of Athena was kept was called the Hekatompedon (heka = 100) which was a hundred Athenian (Attic) feet in length, as the Greek room name indicates. The reflecting pool was filled with water to add humidity to the air and prevent splitting of the ivory elements of the huge chryselephantine (composite gold and ivory) statue. It is worth noting that the statue cost more than the building built to house it and the sculptor Phideas made it so that it's gold panels could be removed, weighed and sold should the need arise. (That proved to be a wise decision because when he was later accused of pilfering some of the gold, he was able to quickly establish his innocence.) [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

“The chryselephantine statue of Athena was a huge work of art by any standard, at least 40 feet (12 meters) in height, a formidable figure in gold and ivory with gems for eyes and outfitted with her full panoply of weapons and symbols. (Chryselephantine comes from the word chryso (gold) and elephantine (ivory). It was a standard technique of the Greek Classical period whereby beaten gold for clothing and ivory for flesh was attached to a wooden armature or core. It is estimated that the gold on the statue alone was worth many millions of dollars. According to early Greek writers, the tyrant Lachares later stripped the goddess of her gold and used it to pay his army. It was said that the statue was later supplied with a coat of gilt by way of replacement.” |

Building the Parthenon

The Parthenon is made almost exclusively of marble found at a site about 18 kilometers away from the Acropolis. About 100,000 tons or marble was used. The marble was shaped at the quarry and transported to Athens and finally hauled up the steep slopes of the Acropolis. It was fortunate that marble was used. Many building made by the ancient Greeks were constructed of limestone, which dissolved over time in the rain and humidity.

Most of the monumental part of the Parthenon were built with 10-ton marble blocks. The craftsmanship is extraordinary. The joints between the blocks are all but invisible even with a magnifying glass. The blocks were fitted together with iron clamps placed into carefully-carved grooves, lead was then poured in the joints to cushion them from seismic shocks and protect them from corrosion.

what the Parthenon looked like in its time

As hard as quarrying, shaping, transporting and fitting these stone blocks is it was not as time-consuming and labor intensive as some of the detail work such as making the flutes (vertical grooves) that run up and down the columns. Manolis Korres, a professor of architecture at the National Technical University of Greece, and coordinator of the Parthenon’s restoration until 2005, estimated that making the flutes in each column was as costly as all the quarrying, hauling and assembly combined.

After the columns were smoothed and polished, a stripling pattern was added to dull the shine and mask the flaws. Ths job required making orderly, precise rows in not only the columns but also the base, floors, columns ad most other surfaces, Korres told Smithsonian magazine, “This was surely one of the most demanding tasks. It must have taken as much as quarter of the total construction expended on the monument.” Athenians were able to devote such attention to detail and still finish the thing in under ten years (based on dates determined from inscribed financial records) it has been surmised using ropes, pulleys and wooden cranes like those used to build their great navy. Some scholars also believe the Athenians possessed chisels, axes and other tools that were stronger and more durable that their modern counterparts and this, combined with superior temple building skills honed over a century and a half, enabled them carve blocks at twice the speed of modern restorers.

There is no denying that the Parthenon construction project was expensive. (The cost, according to public accounts engraved in stone, was 469 silver talents. Attempts to translate that into a modern equivalent aren't entirely satisfactory.) The main building material was Pentelic marble quarried from the flanks of Mt. Pentelikon, located about 10 mi/ 16 km from Athens. (The old Parthenon, the one destroyed by the Persians while it was partway through construction was the first temple to use this kind of marble.) The huge pieces of stone had to be hauled to the building site by oxcart. This structure was, by no means, the largest but what distinguishes the Parthenon from most other temples is the quality and extent of the sculptures. Many of the sculptures were made of the more expensive Parian marble, from the island of Paros, which most sculptors proclaimed the best kind of marble for their work. As a collection that shows Greek art at its zenith the Parthenon marbles (sculptures) are simply without peer. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

“The building itself is a work of art incorporating a number of aesthetic refinements calculated to make it appear as visually perfect as possible. Knowing that long horizontal lines appear to sag, even though they are absolutely straight, horizontal elements were deliberately curved and the vertical columns “fattened” in the middle to compensate for the vagaries of the human eye. This thickening in the middle made it look as though the columns were straining a bit under the weight of the roof, thus making the temple less static, more dynamic. Although the lines and distances in the Parthenon appear to be straight and equal, the geometry has been altered to achieve that illusion. It has been said about this building that “nothing is as it appears”.” |

Parthenon Adornments

The temple itself was adorned with sculpture, of a quality never before, and never since, equaled. The metopes (rectangular panels above the columns) were sculptured with scenes from the Trojan War, and from the Battles of the Athenians and Amazons, the Lapiths and Centaurs, and t he Gods and Giants. In addition, a sculptured frieze above the temple walls depicted the great Panathenaic procession. In this annual celebration, Athenian youths and maidens accompanied the new robe for Athena's statue from Eleusis to the Acropolis itself. The young men on horseback, the maidens, the sacrificial oxeri, and the gods themselves all were depicted, and may be seen today - but not in Athens. [Source: Internet Archive, from vacation.net.gr]

The sculptures, known as the Elgin Marbles, are on view in . London at the British Museum. A few carvings remain in place on the Parthenon, and some fragments are on view in the Acropolis Museum.In addition, the Parthenon had monumental sculpture in both pediments. As Pausanias concisely put it, "As you go into the temple called the Parthenon, everything on the pediment has to do with the birth of Athena; the far side shows Poseidon quarrelling with Athena over the country." As we know, Athena won this contest by producing the first olive tree, and the Athenians did not stint in honoring her with Greece's finest temple. However, the Athenians were always practical: the gold regalia which clad the great statue was designed so that it could be removed for safekeeping. The Athenians had learned what could happen to their sacred sites in the Persian sack of the Acropolis of 480 B.C.

North of the Parthenon is one of the loveliest of all ancient monuments, the delicate Erechtheion, thought to have been built on the very spot where Athena and Poseidon had their contest for possession of Athens. Indeed, some said that the marks of Poseidon's trident were clearly visible in the rock; be that as it may, for some years it has been traditional for an olive tree to grow near the Erechtheion. Alas, visitors today will see the exquisite temple through a screen of scaffolding. Like many of the monuments on the Acropolis , the Erechtheion is feeling the effects of time and urban pollution, and its elegant columns the Caryatid Maidens, have had to be removed (and replaced with copies) for safekeeping.

Beyond the Parthenon is the Belvedere of Queen Amalia, Otho's young bride, who loved to stand here and look out over the new capital of the Kingdom of Greece. One can see why: especially at dawn, when the sounds of the city are stilled, the view of the tile roofs of the Plaka is magical. Beyond sprawls Athens, framed by its mountain ranges, which gave so much marble to the monuments of the Acropolis .

See Separate Article: ELGIN MARBLES: SCULPTURES, FRIEZES AND METOPES FROM THE PARTHENON europe.factsanddetails.com

Painting of the Parthenon

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Evidence that many sculptures from antiquity were not the bright white marble that people imagine today but were originally painted in various colors that have worn away over the millennia has been amassing for decades. Researchers have now found the first traces of paint on the marble sculptures held at the British Museum that came from the Parthenon, the temple to Athena that was built on the Athenian Acropolis in the fifth century B.C. A team led by Giovanni Verri, a conservation scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago, used a technique called visible-induced luminescence imaging to document extensive traces of Egyptian blue, a pigment containing lime, copper, and silicon, on the surface of some of the sculptures. This involved exposing them to red or green light, which causes even the smallest particles of the pigment to emit infrared radiation that can be detected using a digital camera. [Source Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine. March/April 2024]

Egyptian blue appears to have been used on the Parthenon to depict several characteristics. The color represents water, from which Helios, the god of the sun, is shown rising with his chariot. It also seems to denote empty space or air, as in the area between the legs of stools on which the goddesses Demeter and her daughter Persephone sit. Most extensively, Egyptian blue was used to depict designs on woolen garments. A particularly elaborate example is found in the mantle of a figure believed to be the goddess Dione. Along with Egyptian blue, small particles of a purple color were also identified. Verri emphasizes that it is still difficult to say exactly how the artworks would have appeared when first put on display. “The attention and level of complexity that went into carving the sculptures is easily recognizable,” he says. “I would say that the same level of complexity and care went into the painting.”

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Statues at the Parthenon

The chryselephantine statue of Athena was a huge work of art by any standard, at least 40 feet (12 meters) in height, a formidable figure in gold and ivory with gems for eyes and outfitted with her full panoply of weapons and symbols. (Chryselephantine comes from the word chryso (gold) and elephantine (ivory). It was a standard technique of the Greek Classical period whereby beaten gold for clothing and ivory for flesh was attached to a wooden armature or core. It is estimated that the gold on the statue alone was worth many millions of dollars. According to early Greek writers, the tyrant Lachares later stripped the goddess of her gold and used it to pay his army. It was said that the statue was later supplied with a coat of gilt by way of replacement. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

“The figure of Winged Victory- “Nike”- held in the right hand of Athena was six feet tall. In her left hand she supports both a spear and her shield. Entwined inside the shield is a serpent representing Erechtheus, an early king of Athens, son of the earth goddess Gaia but who was raised by Athena. |

“After the Parthenon project was completed Phideas went on to build an even larger and more renowned sculpture, that of the god Zeus, at Olympia. That became one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, and the model for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. What happened to the Athena sculpture? It was taken to Constantinople by the Byzantines by the fifth Century AD. Then, no one is sure when, it disappeared.” |

Parthenon in the A.D. 2nd Century

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “As you enter the temple that they name the Parthenon, all the sculptures you see on what is called the pediment refer to the birth of Athena, those on the rear pediment represent the contest for the land between Athena and Poseidon. The statue itself is made of ivory and gold. On the middle of her helmet is placed a likeness of the Sphinx — the tale of the Sphinx I will give when I come to my description of Boeotia — and on either side of the helmet are griffins in relief.[1.24.6] These griffins, Aristeas1 of Proconnesus says in his poem, fight for the gold with the Arimaspi beyond the Issedones. The gold which the griffins guard, he says, comes out of the earth; the Arimaspi are men all born with one eye; griffins are beasts like lions, but with the beak and wings of an eagle. I will say no more about the griffins. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Parthenon reconstruction

The statue of Athena is upright, with a tunic reaching to the feet, and on her breast the head of Medusa is worked in ivory. She holds a statue of Victory about four cubits high, and in the other hand a spear; at her feet lies a shield and near the spear is a serpent. This serpent would be Erichthonius. On the pedestal is the birth of Pandora in relief. Hesiod and others have sung how this Pandora was the first woman; before Pandora was born there was as yet no womankind. The only portrait statue I remember seeing here is one of the emperor Hadrian, and at the entrance one of Iphicrates,1 who accomplished many remarkable achievements.

“Opposite the temple is a bronze Apollo, said to be the work of Pheidias. They call it the Locust God, because once when locusts were devastating the land the god said that he would drive them from Attica. That he did drive them away they know, but they do not say how. I myself know that locusts have been destroyed three times in the past on Mount Sipylus, and not in the same way. Once a gale arose and swept them away; on another occasion violent heat came on after rain and destroyed them; the third time sudden cold caught them and they died. Such were the fates I saw befall the locusts.

“By the south wall are represented the legendary war with the giants, who once dwelt about Thrace and on the isthmus of Pallene, the battle between the Athenians and the Amazons, the engagement with the Persians at Marathon and the destruction of the Gauls in Mysia. Each is about two cubits, and all were dedicated by Attalus. There stands too Olympiodorus, who won fame for the greatness of his achievements, especially in the crisis when he displayed a brave confidence among men who had met with continuous reverses, and were therefore in despair of winning a single success in the days to come.

“Near the statue of Olympiodorus stands a bronze image of Artemis surnamed Leucophryne, dedicated by the sons of Themistocles; for the Magnesians, whose city the King had given him to rule, hold Artemis Leucophryne in honor.But my narrative must not loiter, as my task is a general description of all Greece. Endoeus1 was an Athenian by birth and a pupil of Daedalus, who also, when Daedalus was in exile because of the death of Calos, followed him to Crete. Made by him is a statue of Athena seated, with an inscription that Callias dedicated the image, but Endoeus made it.

model of the Acropolis

History of the Parthenon After it Was Completed

The dream of Pericles, that the Parthenon would be an imperishable symbol of the greatness of Athens and of the inevitable triumph of civilization over the forces of barbarism, was short-lived. The last of the sculptural ornaments was completed in 432 B.C. but only three years later Pericles and many of his fellow citizens succumbed to a horrific plague that devastated Athens. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

The Parthenon served as a temple to Athena for almost a millennium. Then, in the 6th Century AD, Christian monks from the Greek Orthodox Church took over the building which became known as the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia). The zealous Christians smashed or defaced a number of the sculptures that they felt were pagan or secular and they made minor alterations to the architecture. 700 years passed. |

“In 1204 the French (Franks) invaded Athens and took over control of the Parthenon, renaming it Notre Dame d'Athenes (Our Lady of Athens). It was now a Catholic church. By 1458 Athens was overrun by the Turks who promptly converted the ancient Greek temple into an Islamic mosque, complete with minaret. The Turkish governor took over the adjacent Erechtheum (the temple which features caryatids, draped female figures, in lieu of columns), in which to accommodate his harem. In 1687 the Venetians, who were warring against the Turks, bombarded the Parthenon with mortar and cannon fire. The Turks had felt so confident that the Venetians would not attack this venerable religious building that their women and children were sheltered inside- along with their stores of gunpowder. 300 people and 28 of the Parthenon's columns were destroyed in a massive explosion. |

“The next person to have a major impact on the Parthenon was Lord Elgin, a British statesman and ambassador to Constantinople in 1801, who had obtained permission from Turkish authorities to make drawings and plaster casts of the marvelous sculptures and to “take away any pieces of stone with inscriptions or figures”. (Many pieces of sculpture shattered by the explosion still lay buried or half-buried on the Parthenon grounds.) Lord Elgin's agents were not content for long in picking up broken pieces of sculpture. Soon they were prying pieces off the building and, later, using saws to remove the artwork in sizable chunks. In their defense, they would have been familiar with other destructive practices of the era. The Turks had used some of the Parthenon sculptures for target practice and had lopped the heads off a few figures within reach (likely Pericles among them). In addition, the Turks used whitewash to paint their buildings, which had sprung up all around the Parthenon. Marble, when burned, produces lime and lime mixed with water makes whitewash. It was a recipe that would result in the destruction of both broken and complete marble statuary in Athens and elsewhere.

Today the remains of the Parthenon, the bleached bones of what was once an architectural masterpiece for the ages, provide mute testimony to the glory that was ancient Greece. The artworks that once adorned the marble walls can be found, in bits and pieces still clinging to the remnants of the ancient temple or scattered amongst the world's leading museums in Athens, London, Paris, Munich, Rome, Copenhagen, Vienna, etc. In at least one case a marble sculpture taken from the temple was broken apart and pieces of it can be found in three major cities. Greece has petitioned Britain numerous times seeking the return of the Parthenon marbles from London (which has almost 50 percent of the sculptures), maintaining that the Turks had no right to distribute them to anyone. Britain has refused, saying the collection was legally acquired from the Government then in power and they have no intention of returning anything. And there the matter rests.”

Parthenon in 1800

Mary Beard of the University of Cambridge wrote: “When Elgin's men removed the sculpture from the Parthenon, the building was in a very sorry state. From the fifth century B.C. to the 17th century AD, it had been in continuous use. It was built as a Greek temple, was later converted into a Christian church, and finally (with the coming of Turkish rule over Greece in the 15th century) it was turned into a mosque. Although we think of it primarily as a pagan temple, its history as church and mosque was an even longer one, and no less distinguished. It was, as one British traveller put it in the mid-17th century, 'the finest mosque in the world'. [Source: Mary Beard, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“All that changed in 1687 when, during fighting between Venetians and Turks, a Venetian cannonball hit the Parthenon mosque - temporarily in use as a gunpowder store. Some 300 women and children were amongst those killed, and the building itself was ruined. By 1800 a small replacement mosque had been erected inside the shell, while the surviving fabric and sculpture was suffering the predictable fate of many ancient ruins. |::|

Acropolis: 1) Parthenon; 2) Old Temple of Athena; 3) Erechtheum; 4) Statue of Athena; Promachus; 5) Propylaea; 6) Temple of Athena Nike; 8) Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia; 9) Chalkotheke; 10) Pandroseion; 11) Arrephorion; 12) Altar of Athena; 13) Sanctuary of Zeus; Polieus; 14) Sanctuary of Pandion; 15) Odeon of Herodes Atticus; 16) Stoa of Eumenes; 17) Sanctuary of Asclepius; 18) Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus; 19) Odeum of Pericles; 20) Temenos of Dionysus Eleuthereus; 21) Aglaureion; 22) Peripatos; 23) Clepshydra; 24) Caves of Apollo Hypocraisus, Olympian Zeus and Pan; 25) Sanctuary of Aphrodite and Eros; 26) Peripatos inscription; 27) Cave of Aglauros; 28) Panathenaic way

“On the one hand, the local population was using it as a convenient quarry. A good deal of the original sculpture, as well as the plain building blocks, were reused in local housing or ground down for cement. On the other hand, increasing numbers of travellers and antiquarians from northern Europe were busily helping themselves to anything they could pocket (hence the scattering of pieces of Parthenon sculpture around European museums from Copenhagen to Strasbourg) - and among these collectors was Lord Elgin.” |::|

“The Acropolis hill today is a bare rock, on which are perched the famous monuments of the fifth century B.C. - including the Parthenon. There is the tiny temple of Victory, which stands by the propylaia, or main gateway, to the hilltop, and also the so-called Erechtheum, another shrine of Athena, with its famous line-up of caryatids (columns in the form of female figures). One of the caryatids is now, thanks to Elgin, in the British Museum. |::|

“In Elgin's day it was quite different. The Parthenon stood in the middle of the small village-cum-garrison base that then occupied the hill. It was encroached upon by houses and gardens, and by all kinds of Byzantine, medieval and Renaissance remains. It is quite wrong to imagine Elgin removing works of art from the equivalent of a modern archaeological site - it was more of a seedy shanty town. |::|

Parthenon Archaeology

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “ The Parthenon has suffered mightily. It remained largely intact for nearly 700 years after it was first built, until it was damaged by fire in A.D. 267. It was later turned into a church in the sixth century A.D., which it remained until 1460, when it was converted into a mosque and a minaret was added. In 1687, gunpowder the Turks had stored in the Parthenon exploded when it was hit by Venetian artillery, causing much of the structure to collapse, and severely damaging other sections. And in 1981, a 6.7-magnitude earthquake caused major harm to the northeast corner. For the restoration team, it is a formidable undertaking to correct nearly two millennia of damage to a building that stands as the symbol of a nation. “Because of the size and weight involved, the challenges are immense,” says architect Vassiliki Eleftheriou, “so we started with the most critical problems and went from there. But it’s not easy to ever say we’re finished with something, because some part is always connected to another part.” [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

Among the most urgent of these problems is the damage caused by efforts at anastylosis by Nikolaos Balanos between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of World War II, in particular the poor-quality iron clamps used to hold together broken architectural members or fasten others in new locations. Over the last century, these clamps have rusted, corroded, and expanded, causing the marble to crack, and even to disintegrate. The Parthenon’s ancient builders had also used iron clamps, but had coated them in lead to prevent them from expanding and cracking the stone. Wherever they are found, in the Parthenon and across the Acropolis, Balanos’ clamps are removed and replaced with noncorrosive titanium. After more than three decades in some locations, the new titanium clamps show no sign of trouble, says Eleftheriou.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024