Home | Category: Alexander the Great

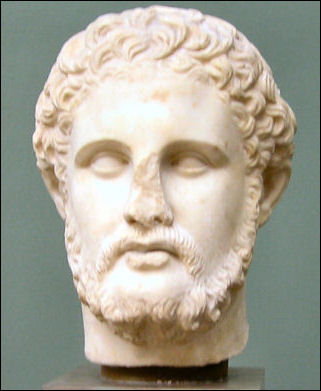

PHILIP II OF MACEDON

Philip II of Macedonia

Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 B.C.), Alexander the Great's father, was the King of Macedonia and Olympias. He became king of Macedon in 359 B.C. at about the age of 23 and ruled for 23 years. An adept warrior, strategist and warrior, he transformed Macedonia from a loose confederation of tribes and cities into a powerful kingdom and introduced an agile cavalry and long pikes to warfare as he overhauled his army.

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: For too long, Philip has been regarded as a minor figure in ancient history, remembered primarily as the father of Alexander the Great. But Philip was a colossus in his own right, a brilliant military leader and politician who transformed Macedonia and built its first empire. [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

Philip II was blinded by an enemy's arrow and was lamed in a battle. He enjoyed wine, lavish feasts and women. He had at least seven wives. Like many upper class Greek men, Philip was also reportedly a bisexual. He showed great courage in battle, was a shrewd politician and patronized the arts, filling his court with writers, artists, philosophers and actors.

Websites: Alexander the Great: An annotated list of primary sources. Livius web.archive.org ; Alexander the Great by Kireet Joshi kireetjoshiarchives.com ;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

See Separate Article: MACEDONIA: HISTORY, PHILLIP II'S TOMBS ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Philip II of Macedonia: Greater Than Alexander” by Richard A. Gabriel, Illustrated, (2010) Amazon.com;

“Philip II of Macedonia” by Ian Worthington (2010) Amazon.com;

“By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire” by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“Philip II of Macedon: A Life From the Ancient Sources” by Alfred S. Bradford Amazon.com;

“Philip of Macedon: by Manolis Andronicos (1992) Amazon.com;

“Philip II, the Father of Alexander the Great: Themes and Issues”

by Edward M. Anson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Philip and Alexander: Kings and Conquerors” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Courts of Philip II and Alexander the Great: Monarchy and Power in Ancient Macedonia” by Frances Pownall, Sulochana R. Asirvatham, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Successors” (Oxford World's Classics) by Diodorus Siculus and Robin Waterfield (2019) Amazon.com;

“Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great: The Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon” by David Grant (2020) Amazon.com;

“Philip II and Macedonian Imperialism” (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Macedonia” by Carol J. King (2017) Amazon.com;

“Macedonia from Philip II to the Roman Conquest” by René Ginouvès. Iannis Akamatis. David Hardy (1994) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander of Macedon” by Peter Green (1974) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

Impact of Philip II on Macedonia and Greece

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Philip II of Macedon took a faction-rent, semi-civilized country of quarrelsome landed nobles and boorish peasants, and made it into an invincible military power. The conquests of Alexander the Great would have been impossible without the military power bequeathed him by his almost equally great father. At the very outset of his reign Philip had to confront sore perils in his own family and among the vassals of his decidedly primitive kingdom.”

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the first half of the fourth century B.C., Greek poleis, or city-states, remained autonomous. As each polis tended to its own interests, frequent disputes and temporary alliances between rival factions resulted. In 360 B.C., an extraordinary individual, Philip II of Macedonia (northern Greece), came to power. In less than a decade, he had defeated most of Macedonia's neighboring enemies: the Illyrians and the Paionians to the west and northwest, and the Thracians to the north and northeast. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org]

Philip II instituted far-reaching reforms at home and abroad. Innovations—improved catapults and siege machinery, as well as a new kind of infantry in which each soldier was equipped with an enormous pike known as a sarissa—placed his armies at the forefront of military technology. In 338 B.C., at the pivotal battle of Chaeronea in Boeotia, Philip II completed what was to be the last phase of his domination when he became the undisputed ruler of Greece. His plans for war against Asia were cut short when he was assassinated in 336 B.C. Excavations of the royal tombs at Vergina in northern Greece give a glimpse of the vibrant wall paintings and rich decorative arts produced for the Macedonian royal court, which had become the leading center of Greek culture.”

Philip II’s Early Life

Philip was born in either 383 or 382 B.C. He was the youngest son of King Amyntas III and Eurydice of Lynkestis. He had two older brothers, Alexander II and Perdiccas III, as well as a sister named Eurynoe. Amyntas later married another woman, Gygaea, with whom he had three sons, Philip's half-brothers Archelaus, Arrhidaeus, and Menelaus. [Source Wikipedia]

After the assassination of Alexander II, Philip was sent as a hostage to Illyria by Ptolemy of Aloros. Philip was later held in Thebes (c. 368–365 B.C.), which at the time was the leading city of Greece. While in Thebes, Philip received a military and diplomatic education from Epaminondas, and lived with Pammenes, who was an enthusiastic advocate of the Sacred Band of Thebes. In 364 B.C. Philip returned to Macedon.

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “When Philip was growing up at the Macedonian court — based at the administrative capital of Pella, with Aigai reserved for royal weddings, funerals and other ceremonial occasions — he learned to hunt, ride and fight in combat. He also studied Greek philosophy, drama and poetry, and absorbed the necessity for ruthlessness in politics. The palace was a viper’s nest of treachery and ambition, and royal children were frequently murdered by rivals to the throne. Macedonia was a violent, unstable, hypermasculine society surrounded by enemies. [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

“In 359 B.C., Philip, 23, saw his older brother King Perdiccas III and 4,000 men get slaughtered by the Illyrians, a rebellious warlike people in Upper Macedonia. His other brother had been murdered in a palace conspiracy, and since Perdiccas III’s heir was a small child, the Macedonian Assembly appointed Philip as regent to the throne, and then as king. “He inherited a very old-fashioned tribal kingdom, with an economy based on livestock,” says archaeologist Ageliki Kottaridi. “Philip had lived in Thebes for a few years, and he brought new ideas from Greece. He introduced coinage. He turned this city into a politically functioning space, and he completely revolutionized the military.”

Philip II of Macedon Takes the Throne

Justin wrote in the A.D. 3rd century in “The History,” Book VII, Chap. 5: “Alexander II [King of Macedon] at the very beginning of his reign purchased peace from the Illyrians [the peoples north and west of Macedon] with a sum of money, giving his brother Philip as a hostage. Some time later, also, he made peace with the Thebans by giving the same hostage, a circumstance which afforded Philip fine opportunities for improving his extraordinary abilities; for being kept as a hostage at Thebes for three years, he received the first rudiments of a boy's education at a city famous for its strict discipline, and in the house of Epaminondas, who was eminent as a philosopher as well as a great general. Not long afterward Alexander perished by a plot of his mother Eurydice, whom Amyntas [her husband] — when she was once convicted of a conspiracy against him — had spared for the sake of their children, little imagining that one day she would be their destroyer. Perdiccas, too — Alexander II's brother — was taken off by like treachery. Horrible, indeed, it was that children should have been deprived of life to gratify the passion of a mother — whom a regard for those very children had saved from the reward for her crimes. The murder of Perdiccas seemed all the viler in that not even the prayers of his little son could win him pity from this mother. Philip, for a long time, acted not as king, but as guardian to this child; but when dangerous wars threatened, and it was too long to wait for the cooperation of a prince who was yet so young, he was forced by the people to take the government upon himself. [Source: William Stearns Davis, “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols., (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. I: Greece and the East, pp. 284-286.

“When he took possession of the throne, great hopes were formed of him by all, both on account of his abilities, which promised that he would prove a great man, and on account of certain old oracles touching Macedonia, which foretold that "when one of the sons of Amyntas should be king, the country should be extremely flourishing," to fulfill which expectations the iniquity of his mother had left only him.

“At the beginning of his reign, when both the treacherous murder of his brother, and the multitude of his enemies, and the poverty of the kingdom exhausted by successive wars, bore hard upon the immature young king, he gained respite from attack by his many foes, some being put off by offers of peace, and others being bought off. However, he attacked such of his enemies as seemed easiest to be subdue, in order that by a victory over them he might confirm the wavering courage of his soldiers, and alter any feelings of contempt which his foes might feel for him. His first conflict was with the Athenians [who sent a fleet to sustain one Manteias, a pretender to Philip's throne] whom he surprised by a stratagem, but — though he might have put them all to the sword — he yet, from dread of a more formidable war, allowed them to depart — uninjured, and without [even] a ransom. Later, leading his army against the Illyrians he slew several thousand of his enemies and took the famous city of Larissa. He then fell suddenly upon Thessaly (when it was fearful of anything but a war) — not from a desire of spoil but because he wished to add the strength of the Thessalian cavalry to his own troops; and he thus incorporated a force of horse and foot in one invincible army.

Philip II of Macedonia Gold Half Stater

“His undertakings having thus far prospered, he married Olympias, daughter of Neoptolemus, king of the Molossians [of Epirus]; her cousin-german, Arrybas, then king of that nation, who had brought up the young princess, and married her sister Troas, doing all he could to promote the union. This proceeding, however, proved to be the cause of Arrybas's downfall, and the beginning of all the evils that afterward befell him; for while he hoped to strengthen his kingdom by this connection with Philip, he was deprived of his crown by that very sovereign, and spent his old age in exile.

“After these proceedings Philip, no longer content to act on the defensive, boldly attacked even those who had not injured him. While he was besieging Methone [a Greek town on the Thermaic Gulf in Macedonia], an arrow shot from the walls, as he was passing, struck out his right eye; but this wound did not make him less active in the siege, nor more resentful towards the enemy. In fact, some days after, he granted them peace when they asked it, on terms not only not rigorous, but even merciful, to the conquered.

Philip’s Creates a Full-Time Regular Army

Philip's military skills and expansionist vision of Macedonia brought him early success. He first had to deal with local rival such as The Illyrians, who killed his brother, as well as the Paeonians and the Thracians, which had sacked and invaded the eastern parts of Macedonia. On the coast the Athenians had landed at Methoni an army under the Macedonian pretender Argaeus II. [Source Wikipedia]

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Macedonia had no full-time professional soldiers, just conscripts and volunteers. Philip instituted regular pay, better training and weapons, a promotion pathway, and a system of cash bonuses and land grants in conquered territories. He invented a highly effective new weapon, the sarissa, a 14- to 18-foot pike with an iron spearhead, and he trained his infantry to fight in a new phalanx formation. [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

Like a traditional Macedonian warrior-king, Philip always led from the front in battle, charging toward the enemy on horseback. In addition to minor wounds, he lost an eye to an arrow, shattered a collarbone, maimed a hand and suffered a near-fatal leg wound, which left him limping for the rest of his life. The Roman historian Plutarch tells us that “he did not cover over or hide his scars, but displayed them openly as symbolic representations, cut into his body, of virtue and courage.”

“Philip inherited 10,000 part-time infantrymen and 600 cavalry, and built this up to 24,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. None of the city-states in Greece had such large standing armies. Nor did they foresee that Philip would use his military, along with cunning diplomacy and seven strategic marriages, to bring nearly all of Greece, a large swath of the Balkans and part of what is now Turkey under ancient Macedonian rule. “This is an incredible achievement for someone they dismissed as a barbarian, and very important for Alexander,” says Kottaridi.

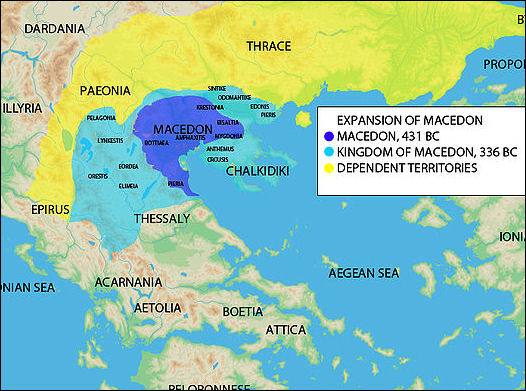

Expansion of Macedon

Philip II’s Conquests and the Rise of Macedon

Most of Philip's tenure as king was spent consolidating his empire in Macedonia and extending it southward into Greece. He forged his kingdom by winning crucial battles and forming important alliances through his marriages. He increased the wealth and status through trade and diplomacy at a time when Macedonia was regarded by other Greek city states such as Athens and Thebes as a barbarian territory even though the Macedonians spoke Greek and considered themselves Greeks.

Philip II took control of Thrace and Thessaly and declared war on Athens and Thebes and their allies. In August 338 B.C., at the Battle of Chaeronea, Macedonia defeated Athens and Philip became the de facto ruler of Greece. He never conquered Athens but formed an alliance with the city after the battle. Philip II's ambition after the victory was to attack Persia, the arch enemy of Greece. In 336 B.C. he began a campaign against the Persians by sending an advance of 10,000 men to Asia Minor. He wasn't with the army because he had to be at the wedding one of his daughters and was murdered there.

Quintus Curtius Rufus wrote: As Dominion increaseth, so doth also the desire to have more; which was well seen in Philip, that still did compass how to grow great by taking from his Neighbours; and lay always like a Spy, waiting an occasion how to catch from every man; whereunto he had an opportunity offered by the Cities of Greece: for whiles one did covet to subdue another, and through ambition were at strife who should be chief. One by one, be brought them all into subjection, perswading the smaller States to move War against the greater; and to serve his purpose, contrived the ways to set them altogether by the ears. But at length, when his practises were perceived, divers Cities fearing his increasing power, confederated, against him as their Common Enemy, but chiefly the Thebans. [Source: Quintus Curtius Rufus (Roman historian, probably A.D.1st century), “The Life and Death of Alexander the Great, King of Macedon,” translated by Robert Codrington (1602-1665), University of Michigan, Oxford University, 2007-10 quod.lib.umich.edu/]

Nevertheless, necessity compelling, they chose him afterwards to be their Captain General against the Spartans, and the Phoceans, who had spoiled the Temple of Apollo. This War he honorably achieved; so that by punishing of their Sacriledge, he got himself great Renown in all those parts. But in the end, observing both those Countries to be brought low with the War, he found means to subdue the one and the other; compelling, as well the Overcomers, as the Overcome, to be his Tributaries. Then he made a Voyage into Cappadocia; where killing and taking prisoners all the Princes thereabout, he reduced the Province to the subjection of Macedon. He conquered Olinthus, and after invaded Thrace: For whereas the two Kings of that Country were at variance about the limits of their Kingdoms, and chose him to be their Arbitrator, he gladly took it upon him: But at the day appointed for the Judgment, he came not thither like a Judge with a Councel, but like a Warriour with an Army; and to part the strife, expelled both Parties from their Kingdoms.

Battle of Chaeronea, 338 B.C.: Philip of Macedon Defeats the Greeks

Battle of Chaeronea

In 338 B.C. at the Battle of Chaeronea, in Chaeronea in Boeotia, Philip II of Macedon defeated an alliance of Greek city-states led by Athens and Thebes. The battle was the culmination of Philip's campaign in Greece (339–338 BC) and marked the end of the Greek system of city-states and the replacement by large military monarchies. On the battle Diodorus Siculus (90-30 B.C.) wrote in “Library of History, Book XVI, Chap. 14: “In the year Charondas was first archon in Athens, Philip, King of Macedon, being already in alliance with many of the Greeks, made it his chief business to subdue the Athenians, and thereby with more ease control all Hellas. To this end he presently seized Elateia [a Phocian town commanding the mountain passes southward], in order to fall on the Athenians, imagining to overcome them with ease; since he conceived they were not at all ready for war, having so lately made peace with him. Upon the taking of Elateia, messengers hastened by night to Athens, informing the Athenians that the place was taken, and Philip was leading on his men in full force to invade Attica. [Source: William Stearns Davis,”Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols., (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. I: Greece and the East, pp. 293-296]

“The Athenian magistrates in alarm had the trumpeters sound their warning all night, and the rumor spread with terrifying effect all through the city. At daybreak the people without waiting the usual call of the magistrate rushed to the assembly place. Thither came the officials with the messenger; and when they had announced their business, fear and silence filled the place, and none of the customary speakers had heart to say a word. Although the herald called on everybody "to declare their minds" — as to what was to be done, yet none appeared; the people, therefore, in great terror cast their eyes on Demosthenes, who now arose, and bade them to be courageous, and forthwith to send envoys to Thebes to treat with the Boeotians to join in the defense of the common liberty; for there was no time (he said) to send an embassy for aid elsewhere, since Philip would probably invade Attica within two days, and seeing he must march through Boeotia, the only aid was to be looked for there.

“The people approved of his advice, and a decree was voted that such an embassy should be sent. As the most eloquent man for the task, Demosthenes was pitched upon, and forthwith he hastened away [to Thebes. — Despite past hostilities between Athens and Thebes, and the counter-arguments of Philip's envoys, Demosthenes persuaded Thebes and her Boeotian cities that their liberty as well as that of Athens was really at stake, and to join arms with the Athenians.] . . .When Philip could not prevail on the Boeotians to join him, he resolved to fight them both. To this end, after waiting for reinforcements, he invaded Boeotia with about thirty thousand foot and two thousand horse. . . .

“Both armies were now ready to engage; they were equal indeed in courage and personal valor, but in numbers and military experience a great advantage lay with the king. For he had fought many battles, gained most of them, and so learned much about war, but the best Athenian generals were now dead, and Chares — the chief of them still remaining — differed but little from a common hoplite in all that pertained to true generalship. About sunrise [Source: Chaeronea in Boeotia] the two armies arrayed themselves for battle. The king ordered his son Alexander, who had just become of age, yet already was giving clear signs of his martial spirit, to lead one wing, though joined to him were some of the best of his generals. Philip himself, with a picked corps, led the other wing, and arranged the various brigades at such posts as the occasion demanded. The Athenians drew up their army, leaving one part to the Boeotians, and leading the rest themselves.

“At length the hosts engaged, and the battle was fierce and bloody. It continued long with fearful slaughter, but victory was uncertain, until Alexander, anxious to give his father proof of his valor---and followed by a courageous band---was the first to break through the main body of the enemy, directly opposing him, slaying many; and bore down all before him---and his men, pressing on closely, cut to pieces the lines of the enemy; and after the ground had been piled with the dead, put the wing resisting him in flight. The king, too, at the head of his corps, fought with no less boldness and fury, that the glory of victory might not be attributed to his son. He forced the enemy resisting him also to give ground, and at length completely routed them, and so was the chief instrument of the victory.

Battle of Chaeronea

“Over one thousand Athenians fell, and two thousand were made prisoners. A great number of Boeotians, too, perished, and many more were captured by the enemy. . . [After some boastful conduct by the king, thanks to the influence of Demades, an Athenian orator who had been captured], Philip sent ambassadors to Athens and renewed the peace with her [on very tolerable terms, leaving her most of her local liberties]. He also made peace with the Boeotians, but placed a garrison in Thebes. Having thus struck terror into the leading Greek states, he made it his chief effort to be chosen generalissimo of Greece. It being noised abroad that he would make war upon the Persians, on behalf of the Greeks, in order to avenge the impieties committed by them against the Greek gods, he presently won public favor over to his side throughout Greece. He was very liberal and courteous, also, to both private citizens and communities, and proclaimed to the cities that he wished to consult with them as to the common good.' Whereupon a general council [of the Greek cities] was convened at Corinth, where he declared his design of making war on the Persians, and the reasons he hoped for success; and therefore desired the Council to join him as allies in the war. At length he was created general of all Greece, with absolute power, and having made mighty preparations and assigned the contingents to be sent by each city, he returned to Macedonia [where, soon after, he was murdered by Pausanius, a private enemy].”

Impact on the Greeks of Philips Victory at Chaeronea

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “For the disaster at Chaeronea was the beginning of misfortune for all the Greeks, and especially did it enslave those who had been blind to the danger and such as had sided with Macedon. Most of their cities Philip captured; with Athens he nominally came to terms, but really imposed the severest penalties upon her, taking away the islands and putting an end to her maritime empire. For a time the Athenians remained passive, during the reign of Philip and subsequently of Alexander. But when on the death of Alexander the Macedonians chose Aridaeus to be their king, though the whole empire had been entrusted to Antipater, the Athenians now thought it intolerable if Greece should be for ever under the Macedonians, and themselves embarked on war besides inciting others to join them. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918] “The cities that took part were, of the Peloponnesians, Argos, Epidaurus, Sicyon, Troezen, the Eleans, the Phliasians, Messene; on the other side of the Corinthian isthmus the Locrians, the Phocians, the Thessalians, Carystus, the Acarnanians belonging to the Aetolian League. The Boeotians, who occupied the Thebaid territory now that there were no Thebans left to dwell there, in fear lest the Athenians should injure them by founding a settlement on the site of Thebes, refused to join the alliance and lent all their forces to furthering the Macedonian cause. Each city ranged under the alliance had its own general, but as commander-in-chief was chosen the Athenian Leosthenes, both because of the fame of his city and also because he had the reputation of being an experienced soldier. He had already proved himself a general benefactor of Greece. All the Greeks that were serving as mercenaries in the armies of Darius and his satraps Alexander had wished to deport to Persia, but Leosthenes was too quick for him, and brought them by sea to Europe. On this occasion too his brilliant actions surpassed expectation, and his death produced a general despair which was chiefly responsible for the defeat.

“A Macedonian garrison was set over the Athenians, and occupied first Munychia and afterwards Peiraeus also and the Long Walls. On the death of Antipater Olympias came over from Epeirus, killed Aridaeus, and for a time occupied the throne; but shortly afterwards she was besieged by Cassander, taken and delivered up to the people. Of the acts of Cassander when he came to the throne my narrative will deal only with such as concern the Athenians. He seized the fort of Panactum in Attica and also Salamis, and established as tyrant in Athens Demetrius the son of Phanostratus, a man who had won a reputation for wisdom. This tyrant was put down by Demetrius the son of Antigonus, a young man of strong Greek sympathies. But Cassander, inspired by a deep hatred of the Athenians, made a friend of Lachares, who up to now had been the popular champion, and induced him also to arrange a tyranny. We know no tyrant who proved so cruel to man and so impious to the gods.”

Growth of the Greek Kingdom of Macedon

Athens Revolts Against the Macedonians

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “Although Demetrius the son of Antigonus was now at variance with the Athenian people, he notwithstanding deposed Lachares too from his tyranny, who, on the capture of the fortifications, escaped to Boeotia. Lachares took golden shields from the Acropolis, and stripped even the statue of Athena of its removable ornament; he was accordingly suspected of being a very wealthy man, and was murdered by some men of Coronea for the sake of this wealth. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

After freeing the Athenians from tyrants Demetrius the son of Antigonus did not restore the Peiraeus to them immediately after the flight of Lachares, but subsequently overcame them and brought a garrison even into the upper city, fortifying the place called the Museum. This is a hill right opposite the Acropolis within the old city boundaries, where legend says Musaeus used to sing, and, dying of old age, was buried. Afterwards a monument also was erected here to a Syrian. At the time to which I refer Demetrius fortified and held it.

“But afterwards a few men called to mind their forefathers, and the contrast between their present position and the ancient glory of Athens, and without more ado forth with elected Olympiodorus to be their general. He led them against the Macedonians1, both the old men and the youths, and trusted for military success more to enthusiasm than to strength. The Macedonians came out to meet him, but he over came them, pursued them to the Museum, and captured the position.

“So Athens was delivered from the Macedonians, and though all the Athenians fought memorably, Leocritus the son of Protarchus is said to have displayed most daring in the engagement. For he was the first to scale the fortification, and the first to rush into the Museum; and when he fell fighting, the Athenians did him great honor, dedicating his shield to Zeus of Freedom and in scribing on it the name of Leocritus and his exploit. This is the greatest achievement of Olympiodorus, not to mention his success in recovering Peiraeus and Munychia; and again, when the Macedonians were raiding Eleusis he collected a force of Eleusinians and defeated the invaders. Still earlier than this, when Cassander had invaded Attica, Olympiodorus sailed to Aetolia and induced the Aetolians to help. This allied force was the main reason why the Athenians escaped war with Cassander. Olympiodorus has not only honors at Athens, both on the Acropolis and in the town hall but also a portrait at Eleusis. The Phocians too of Elatea dedicated at Delphi a bronze statue of Olympiodorus for help in their revolt from Cassander.

Assassination of Philip II

In 336 B.C., at the wedding one of his daughters, Philip II was fatally stabbed through the heart as he entered the outdoor theater where the wedding was held by a disaffected bodyguard and perhaps former lover. Some believed that Alexander may have been involved in the murder but most historians believe that was unlikely. It seems more likely that his estranged fourth wife Olympias egged on the bodyguard to kill Philip because she was upset over being recently rejected in favor of a younger wife.

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: By 336 B.C., after little more than two decades on the throne, Philip had transformed Macedonia from a struggling backwater into an imperial superpower. Now he was planning to invade the Persian Empire in Asia Minor. He had already sent an advance contingent of 10,000 troops. The rest of the army would join them after the marriage of his daughter Cleopatra (no connection with the Egyptian queen) in October. He turned the wedding into a huge gala for dignitaries and ambassadors from all over Greece and the Balkans. “They crowned Philip with golden wreaths,” says Kottaridi. “The wedding took place right here in the palace and there was a huge feast. The next morning they all gathered at the theater for the final celebration.” [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

“It began with a sunrise procession. Twelve men came through the theater holding up statues of the 12 Olympian gods. They were followed by a statue of Philip, suggesting that he had crossed the permeable line between men and gods and was now divine. Then came one-eyed Philip himself, scarred and limping, but radiating power and authority. He wore a white cloak and a golden crown, and most dramatically, he was unarmed. Macedonian men typically wore their weapons, but Philip wanted to convey his invincibility. When he reached the center of the theater, he stopped and faced the cheering crowd.

“Suddenly one of his bodyguards stabbed him in the chest with a dagger, “driving the blow right through the ribs,” according to the historian Diodorus. Philip fell dead and his white cloak turned red. The assassin sprinted to the city gates, where horses were waiting for him. Three bodyguards who were friends of Alexander gave chase, caught him and killed him on the spot.

Plutarch on Philip II's Assassination

Pausanius assassinates Philip II by Andre Castaigne (1899)

Plutarch wrote in Alexander 9-10: “While Philip went on his expedition against the Byzantines, he left Alexander, then sixteen years old, his lieutenant in Macedonia, committing the charge of his seal to him...But the disorders of his family, chiefly caused by his new marriages and attachments (the troubles that began in the women's chambers spreading, so to say, to the whole kingdom), raised various complaints and differences between them, which the violence of Olympias, a woman of a jealous and implacable temper, made wider, by exasperating Alexander against his father. Among the rest, this accident contributed most to their falling out. At the wedding of Cleopatra, whom Philip fell in love with and married, she being much too young for him, her uncle Attalus in his drink desired the Macedonians would implore the gods to give them a lawful successor to the kingdom by his niece. This so irritated Alexander, that throwing one of the cups at his head, "You villain," said he, "what, am I then a bastard?" Then Philip, taking Attalus's part, rose up and would have run his son through; but by good fortune for them both, either his over-hasty rage, or the wine he had drunk, made his foot slip, so that he fell down on the floor. At which Alexander reproachfully insulted over him: "See there," said he, "the man who makes preparations to pass out of Europe into Asia, overturned in passing from one seat to another." After this debauch, he and his mother Olympias withdrew from Philip's company, and when he had placed her in Epirus, he himself retired into Illyria. [Source: Plutarch, Alexander 9-10, Internet Archive, Reed]

“About this time, Demaratus the Corinthian, an old friend of the family, who had the freedom to say anything among them without offence, coming to visit Philip, after the first compliments and embraces were over, Philip asked him whether the Grecians were at amity with one another. "It ill becomes you," replied Demaratus, "to be so solicitous about Greece, when you have involved your own house in so many dissensions and calamities." He was so convinced by this seasonable reproach, that he immediately sent for his son home, and by Demaratus's mediation prevailed with him to return.

“But this reconciliation lasted not long; for when Pixodorus, viceroy of Caria, sent Aristocritus to treat for a match between his eldest daughter and Philip's son, Arrhidaeus, hoping by this alliance to secure his assistance upon occasion, Alexander's mother, and some who pretended to be his friends, presently filled his head with tales and calumnies, as if Philip, by a splendid marriage and important alliance, were preparing the way for settling the kingdom upon Arrhidaeus. In alarm at this, he despatched Thessalus, the tragic actor, into Caria, to dispose Pixodorus to slight Arrhidaeus, both illegitimate and a fool, and rather to accept of himself for his son-in-law. This proposition was much more agreeable to Pixodorus than the former. But Philip, as soon as he was made acquainted with this transaction, went to his son's apartment, taking with him Philotas, the son of Parmenio, one of Alexander's intimate friends and companions, and there reproved him severely, and reproached him bitterly, that he should be so degenerate, and unworthy of the power he was to leave him, as to desire the alliance of a mean Carian, who was at best but the slave of a barbarous prince. Nor did this satisfy his resentment, for he wrote to the Corinthians to send Thessalus to him in chains, and banished Harpalus, Nearchus, Erigyius, and Ptolemy, his son's friends and favourites, whom Alexander afterwards recalled and raised to great honour and preferment.

“Not long after this, Pausanias, having had an outrage done to him at the instance of Attalus and Cleopatra, when he found he could get no reparation for his disgrace at Philip's hands, watched his opportunity and murdered him. The guilt of which fact was laid for the most part upon Olympias, who was said to have encouraged and exasperated the enraged youth to revenge; and some sort of suspicion attached even to Alexander himself, who, it was said, when Pausanias came and complained to him of the injury he had received, repeated the verse out of Euripides's Medea: "On husband, and on father, and on bride." However, he took care to find out and punish the accomplices of the conspiracy severely, and was very angry with Olympias for treating Cleopatra inhumanly in his absence.”

Why Was Philip II Assassinated?

According to a story, as recorded by ancient historian Diodorus of Sicily, Philip's bodyguard and lover Pausanias became jealous that the king was doting on another man (also, confusingly, named Pausanias). The first Pausanias mocked the second one to such a degree he committed suicide. To get revenge, Attalus — the second Pausanias' friend and uncle of one of Philip II's wives —sexually assaulted the first Pausanias after getting him drunk. Pausanias raised the issue to Philip II, who promoted him but did not punish Attalus. Pausanias then assassinated Philip II to avenge his own honor. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 20, 2015 ]

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The assassin was Pausanias of Orestes in Upper Macedonia, and Philip had recently jilted him for a new male lover. Pausanias was then gang-raped by a man named Attalus and his cronies, and turned over to the stable hands for more sexual abuse. When Pausanias reported this outrage to Philip, the king did nothing. Did Pausanias murder Philip for not punishing Attalus, as some scholars believe? Or was Pausanias the paid instrument of more powerful individuals who wanted Philip dead, as other scholars believe? [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

“We know that Olympias loathed her husband and yearned for Alexander to take the throne. King Darius II of Persia is another suspect with an obvious motive: Philip was preparing to invade his empire. Prominent Athenians are under suspicion, because they resented Macedonian rule. The finger has also been pointed at Alexander, who had quarreled with his father and would gain the throne with his death. “That last theory is a foolish slander against Alexander, Kottaridi says. She suspects a plot by a rival faction of nobles. Palace intrigues had long been a blood sport in Macedonia. The kings at Aigai — Philip was 46 — almost never died of old age.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024