Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory

THUCYDIDES

Thucydides Thucydides (471?-400? B.C.) wrote extensively about events in Greece and told the story of the draining, disastrous 30-year Peloponnesian War that destroyed Athens when it was in its prime in “History of the Peloponnesian War”. Little known about his life other than that he was an soldier and an officer. One of the few times he talks about himself is when he mentions he survived the plague. [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, January 12, 2004]

Tracy Lee Simmons wrote in the Washington Post: “One of the most eminently, and now, predictably, quotable figures of the classical world, Thucydides assuredly deserves his press. Few so well understood the machinations of he human heart and mind when facing the extremities of the human predicament — plague, betrayal, defeat, and the abject humiliation of war — and fewer still could distill the hard-won wisdom of experience into tight, shimmering phrases and radiant lapidary passages.”

Thucydides was a participant in the events he described. He caught the plague he detailed with such precision. He was also far from a distant observer of the Peloponnesian War: he was a general high in the Athenian command early in the war who was forced into exile after he failed to prevent the Spartans from capturing the northern city of Amphipolis in 422. He wrote his account years later in part to defend his actions and in the end puts the blame on the demise of Athens on democracy and its demagogue politicians while arguing it was enlightened military that almost saved the day.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MAJOR EVENTS DURING THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MITYLENIAN DEBATE DURING THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR europe.factsanddetails.com

Links to Works by Thucydides

History of the Peloponnesian War, 431 B.C. MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

History of the Peloponnesian War, 431 B.C. Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

History of the Peloponnesian War, 431 B.C. in Ancient Greek Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

2ND Study Guide, Brooklyn College, now Internet Archive web.archive.org;

2ND 11th Britannica: Thucydides sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“History of the Peloponnesian War” by Thucydides (1834) Amazon.com;

“A War Like No Other” by Victor Davis Hanson (2005) Amazon.com;

“Thucydides, The Reinvention of History” by Donald Kagan, (Viking, 2009); Kagan is a professor of classics and history at Yale. Amazon.com;

“The Portable Greek Historians: The Essence of Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius” (Portable Library) by M. I. Finley and M. Finley (1977) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Historians” by T. James J. Luce Amazon.com;

“The Essential Greek Historians” by Stanley Burstein (2022) Amazon.com;

“Readings in the Classical Historians” by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“The Landmark edited by Robert B. Strassler (Pantheon, 2008) Amazon.com

Thucydides’s Life

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “Materials for his biography are scanty, and the facts are of interest chiefly as aids to the appreciation of his life's labour, the History of the Peloponnesian War. The older view that he was probably born in or about 471 B.C., is based on a passage of Aulus Gellius, who says that in 431 Hellanicus "seems to have been" sixtyfive years of age, Herodotus fiftythree and Thucydides forty (Noct. att. xv. 23). The authority for this statement was Pamphila, a woman of Greek extraction, who compiled biographical and historical notices in the reign of Nero. The value of her testimony is, however, negligible, and modern criticism inclines to a later date, about 460 (see Busolt, Gr. Gesch. iii., pt. 2, P. 621). Thucydides' father Olorus, a citizen of Athens, belonged to a family which derived wealth and influence from the possession of goldmines at Scapte Hyle, on the Thracian coast opposite Thasos, and was a relative of his elder namesake, the Thracian prince, whose daughter Hegesipyle married the great Miltiades, so that Cimon, son of Miltiades, was possibly a connexion of Thucydides (see Busolt, ibid., p. 618). It was in the vault of the Cimonian family at Athens, and near the remains of Cimon's sister Elpinice, that Plutarch saw the grave of Thucydides. Thus the fortune of birth secured three signal adYantages to the future historian: he was rich; he had two homes-one at Athens, the other in Thrace-no small aid to a comprehensive study of the conditions under which the Peloponnesian War was waged; and his family connexions were likely to bring him from his early years into personal intercourse with the men who were shaping the history of his time. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

Thucydides at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin

“The development of Athens during the middle of the 5th century was, in itself, the best education which such a mind as that of Thucydides could have received. The expansion and consolidation of Athenian power was completed, and the inner esources of the city were being applied to the CIMON; PERICLES). Yet the History tells us nothing of the literature, the art or the social life under whose influences its author had grown up. The "Funeral Oration" contains, indeed, his general testimony on the value and the charm of those influences. But he leaves s to supply all examples and details for ourselves. Beyond passing reference to public "festivals," and to "beautiful surroundings in private life," he makes no attempt to define hose "recreations for the spirit" which the Athenian genius ad provided in such abundance. He alludes to the newlyuilt Parthenon only as containing the treasury; to the statue Athena Parthenos which it enshrined, only on account of the gold which, at extreme need, could be detached from the image; to the Propylaea and other buildings with which Athens ad been adorned under Pericles, only as works which had reuced the surplus of funds available for the war. He makes no reference to Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes; the architect Ictinus; the sculptor Pheidias; the physician Hippocrates; the philosophers Anaxagoras and Socrates. Herodotus he had dealt with this period, would have found countless casions for invaluable digressions on men and manners, on letters and art; and we might almost be tempted to ask hether his more genial, if laxer, method does not indeed rrespond better with a liberal conception of the historian's office. No one can do full justice to Thucydides, or appreciate the true completeness of his work, who has not faced is question, and found the answer to it.

“It would be a hasty judgment which inferred from the omissions of the History that its author's interests were exclusively political. Thucydides was not writing the history of a period. His subject was an event-the Peloponnesian War-a war, as he believed, of unequalled importance, alike in its direct results and in its political significance for all time. To his task, thus defined, he brought an intense concentration of all his faculties. He worked with a constant desire to make each successive incident of the war as clear literature more graphic than his description of the plague at Athens, or than the whole narrative of the Sicilian expedition. But the same temper made himresolute in excluding irrelevant topics. The social life of the time, the literature and the art did not belong to his subject.

“The biography which bears the name of Marcellinus states that Thucydides was the disciple of Anaxagoras in philosophy and of Antiphon in rhetoric. There is no evidence to confirm this tradition. But Thucydides and Antiphon at least belong to the same rhetorical school and represent the same early stage of Attic prose. Both writers used words of an antique or decidedly poetical cast; both point verbal contrasts by insisting on the precise difference between terms of similar import; and both use metaphors somewhat bolder than were congenial to Greek prose in its riper age. The differences, on the other hand, between the style of Thucydides and that of Antiphon arise chiefly from two general causes. First, Antiphon wrote for hearers, Thucydides for readers; the latter, consequently, can use a degree of condensation and a freedom in the arrangement of words which would have been hardly possible for the former. Again, the thought of Thucydides is often more complex than any which Antiphon undertook to interpret; and the greater intricacy of the historian's style exhibits the endeavour to express eachthought. Few things in the history of literary prose are more interesting than to watch that vigorous mind in its struggle to mould a language of magnificent but immature capabilities. The obscurity with which Thucydides has sometimes been reproached often arises from the very clearness with which a complex idea is present to his mind, and his strenuous effort to present it in its entirety. He never sacrifices thought to language, but he will sometimes sacrifice language to thought. A student may always be consoled by the reflection that he is not engaged in unravelling a mere rhetorical tangle. Every light on the sense will be a light on the words; and when, as is not seldom the case, Thucydides comes victoriously out of this struggle of thought and language, having achieved perfect expression of his meaning in a sufficiently lucid form then his style rises into an intellectual brilliancy-thoroughiy manly, and also penetrated with intense feeling-which nothing in Greek prose literature surpasses.

“The uncertainty as to the date of Thucydides' birth renders futile any discussion of the fact that before 431 he took no prominent part in Athenian politics. If he was born in 455, the fact needs no explanation; if in 471, it is possible that his opportunities were modified by the necessity of frequent visits to Thrace, where the management of such an important property as the goldnlines must have claimed his presence. The manner in which he refers to his personal influence in that region is such as to su~gest that he had sometimes resided there (iv. 1O5, I). He was at Athens in the spring of 430, when the plague broke out. If his account of the symptoms has nct enabled physicians to agree on a diagnosis of the malady, it is at least singularly full and vivid. He had himself been attacked by the plague; and, as he briefly adds, "he had seen others suffer." The tenor of his narrative would warrant the inference that he had been one of a few who were active in ministering to the sufferers.

Thucydides’ Military and Political Career

Thucydides at the Austrian Parliament Building

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “The turning point in the life of Thucydides came in the winter of 424. He was then forty seven (or, according to Busolt, about thirty six), and for the first time he is found holding an official position. He was one of two generals entrusted with the command of the regions towards Thrace ... a phramore special reference to the Chalcidic peninsula. His colleague in the command was Eucles. About the end of November 424 Eucles was in Amphipolis, the stronghold of Athenian power in the northwest. To guard it with all possible vigilance was a matter of peculiar urgency at that moment. The ablest of Spartan leaders, Brasidas (q.v.), was in the Chalcidic peninsula, where he had already gained rapid success; and part of the popu!ation between that peninsula and Amphipolis was known to be disaffected to Athens. Under such circumstances we might have expected that Thucydides, who had seven ships of war with him, would have been ready to cooperate with Eucles. It appears, however, that, with his ships, he was at the island of Thasos when Brasidas suddenly appeared before Amphipolis. Eucles sent in all haste for Thucydides, who arrived with his ships from Thasos just in time to beat off the enemy from Eion at the mouth of the Strymon, but not in time to save Amphipolis. The profound vexation and dismay felt at Athens found expression in the punishment of Thucydides, who was exiled. Cleon is said to have been the prime mover in his condemnation; and this is likely enough. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“From 423 to 404 Thucydides lived on his property in Thrace, but much of his time appears to have been spent in travel. He visited the countries of the Peloponnesian allies-recommended to them by his quality as an exile from Athens; and he thus enjoyed the rare advantage of contemplating the war from various points of view. He speaks of the increased leisure which his banishment secured to his study of events. He refers partly, doubtless, to detachment from Athenian politics, partly also, we may suppose, to the opportunity of visiting places signalized by recent events and of examining their topography. The local knowledge which is often apparent in his Sicilian books may have been acquired at this period. The mind of Thucydides was naturally judicial, and his impartiality-which seems almost superhuman by contrast with Xenophon's Hellenica- was in some degree a result of temperament. But it cannot be doubted that the evenness with which he holds the scales was greatly assisted by his experience during these years of exile.

“His own words make it clear that he returned to Athens, at least for a time, in 404, though the precise date is uncertain. The older view (cf. Classen) was that he returned some six months after Athens surrendered to Lysander. More probably he was recalled by the special resolution carried by Oenobius prior to the acceptance of Lysander's terms (Busolt, ibid., p. 628). He remained at Athens only a short time, and retired to his property in Thrace, where he lived till his death, working at his History. The preponderance of testimony certainly goes to show that he died in Thrace, and by violence. It would seem that, when he wrote chapter II6 of his third book, be was ignorant of an eruption of Etna which took place in 396. There is, indeed, strong reason for thinking that he did not live later than 399. His remains were brought to Athens and laid in the vault of Cimon's family, where Plutarch (Cimon, 4) saw their restingplace. The abruptness with which the History breaks off agrees with the story of a sudden death. The historian's daughter is said to have saved the unfinished work and to have placed it in the hands of an editor. This editor, according to one account, was Xenophon, to whom Diogenes Laertius (ii. 6, 13) assigns the credit of having "brought the work into reputation, when he might have suppressed it." The tradition is, however, very doubtful; it may have been suggested by a feeling that no one then living could more appropriately have discharged the office of literary executor than the writer who, in bis Hellenica, continued the narrative.

Thucydides’ “History of the Peloponnesian War”

Thucydides’s “History of the Peloponnesian War” is the only extant eyewitness account of the first twenty years of the war. He said he began taking notes “at the very outbreak” of the conflict because he had hunch it would be — a great war and more worthy writing about than any of those which had taken place in the past.” His accounts end in mid sentence during the description of a naval battle in 411 but we can tell from other references in his work that he was around to see the war end in 404 B.C.

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “At the outset of the “History” Thucydides indicates his general conception of his work, and states the principles which governed its composition. His purpose had been formed at the very beginning of the war, in the conviction that it would prove more important than any event of which Greeks had record. The leading belligerents, Athens and Sparta, were both in the highest condition of effective equipment. The whole Hellenic world- including Greek settlements outside of Greece proper-was divided into two parties, either actively helping one of the two combatanu or meditating such action. Nor was the movement confined within even the widest limits of Hellas, the "barbarian" world also was affected by it-the nonHellenic populations of Thrace Macedonia Epirus, Sicily and, finally, the Persian kingdom itseif. The aim of Thucydides was to preserve an accurate record of this war, not only in view of the intrinsic interest and importance of the facts, but also in order that these facts might be permanent sources of political teaching to posterity. His hope was, as he says, that his History would be found profitable by "those who desire an exact knowledge of the past as a key to the future, which in all probability will repeat or resemble the past. The work is meant to be a possession for ever, not the rhetorical triumph of an hour." As this context shows, the oftquoted phrase, "a possession for ever," had, in its author's meaning, a more definite import than any mere anticipation of abiding fame for his History. It referred to the permanent value of the lessons which his History contained. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Thucydides stands alone among the men of his own days, and has no superior of any age, in the width of mental grasp which could seize the general significance of particular events. The political education of mankind began in Greece, and in the time of Thucydides their political life was still young. Thucydides knew oniy the smaU citycommonwealth on the one hand, and on the other the vast barbaric kingdom; and yet, as has been well said of him "there is hardly a problem in the science of government which the statesman will not find, if not solved, at any rate handled, in the pages of this universal master."

“Such being the spirit in which he approached his task, it is interesting to inquire what were the points which he himself considered to be distinctive in his method of executing it. His Greek predecessors in the recording of events had been, he conceived, of two classes. First, there were the epic poets, with Homer at their head, whose characteristic tendency, in the eyes of Thucydides, is to exaggerate the greatness or splendour of things past. Secondly, there were the Ionian prose writers whom he calls "chroniclers" (see LOGOGRAPH), whose general object was to diffuse a knowledge of legends preserved by oral tradition and of written documents-usually lists of officials or genealogies-preserved in public archives, and they published their materials as they found them, without criticism. Thucydides describes their work by the word xuntiqinai, but his own by xuggraqein-the difference between the terms answering to that, between compilation of a somewhat mechanical kind and historic-composition in a higher sense. The vice of the "chroniclers," in his view, is that they cared only for popularity, and took no pains to make their narratives trustworthy. Herodotus was presumably regarded by him as in the same general category.”

Thucydides as a Historian

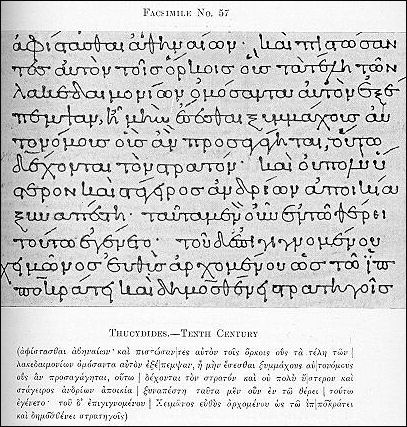

Thucydides manuscript Thucydides is regarded as a much better historian than Herodotus, who tended to romanticize and exaggerate. Thucydides named his sources and included documents to back up his claims. His style was terse and skeptical. And his emphasis on getting his facts straight makes him such a rich source of moral guidance and historical wisdom. It was Thucydides after all who first summed up the pattern of history when he said disasters “have occurred and always will occur as long as he nature of mankind remains the same.”

Thucydides wrote: “With reference to the narrative of events, far from permitting myself to derive it from the first sources that came to hand, I did not even trust my impressions.” He made sure he tested the accuracy of his reports “by the most severe and detailed tests possible” and found this required “some labor from the want of coincidence between accounts of different eye-witnesses.”

Thucydides added that “the absence of romance from my history will...detract somewhat from its interest.” However — if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the interpretation of the future, which in the course of human events must resemble if not reflect it.”

But to achieve his goal of eschewing “literary charm” and myth, he made up dialogues and speeches — that no one really heard — to get at what the participants must have been thinking at the time. He wrote “My method has been to make the speakers say what in my opinion, was called for by each situation.”:

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “In contrast with these predecessors Thucydides has subjected his materials to the most searching scrutiny. The ruling principle of his work has been strict adherence to carefully verified facts. "As to the deeds done in the war, I have not thought myself at liberty to record them on hearsay from the first informant or on arbitraly conjecture. My account rests either on personal knowledge or on the closest possible scrutiny of each statement made by others. The process of research was laborious, because conflicting accounts were given by those who had witnessed the several events, as partiality swayed or memory served them." It is “therefore, well to consider their nature and purpose rather closely. The speeches constitute between a fourth and a fifth part of the History. If they were eliminated, an admirable narrative would indeed remain, with a few comments, usually brief, on the more striking characters and events. But we shourd lose all the most vivid light on the inner workings of the Greek political mind, on the motives of the actors and the arguments which they used-in a word, on the whole plan of contemporary feeling and opinion. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“ To the speeches is due no no small measure the imperishable intellectual interest of the History, since it is chiefly by the speeches that the facts of the Peloponnesian War are so lit up with keen thought as to become illustrations of general laws, and to acquire a permanent suggestiveness for the student of politics. When Herodotus made his persons hold conversations or deliver speeches, he was following the precedent of epic poetry; his tone is usually colloquial rather than rhetorical; he is merely making thought and motive vivid in the way natural to a simple age. Thucydides is the real founder of the tradition by which historians were so long held to be warranted in introducing set speeches of their own composition. His own account of his practice is given in the following words: "As to the speeches made on the eve of the war, or in its course, I have found it difficult to retain a memory of the precise words which I had heard spoken; and so it was with those who brought me reports. But I have made the persons say what it seemed to me most opportune for them to say in view of each situation; at the same time I have adhered as closely as possible to the general sense of what was actually said." So far as the language of the speeches is concerned, then, Thucydides plainly avows that it is mainly or wholly his own. As a general rule, there is little attempt to mark different styles. The case of Peric!es, whom Thucydides must have repeatedly heard, is probably an exception; the Thucydidean speeches of Pericles offer several examples of that bold imagery which Aristotl3 and Plutarch agree in ascribing to him, while the "Funeral Oration," especially, has a certain majesty of rhythm a certain union of impetuous movement with lofty grandeur, which the historian has given to no other speaker. Such strongly marked characteristics as the curt bluntness of the Spartan ephor Sthenelaidas, or the insolent vehemence of Alcibiades, are also indicated But the dramatic truth of the speeches generally resides in the matter, not in the form. In regard to those speeches which were delivered at Athens before his banishment in 424-and seven such speeches are contained in the History-Thucydides could rely either on his own recollection or on the sources accessible to a resident citizen. In these cases there is good reason to believe that he has reproduced the substance of what was actually said In other cases he had to trust to more or less imperfect reports of the "general sense"; and in some instances, no doubt, the speech represents simply his own conception of what it would have been "most opportune" to say. The most evident of such instances occur in the addresses of leaders to their troops. The historian's aim in these mihtary harangues-which are usually short-is to bring out the points of a strategical situation; a modern writer would have attained the object by comments prefixed or subjoined to his account of the battle. The comparative indifference of Thucydides to dramatic verisimilitude in these military orations is curiously shown by the fact that the speech of the general on the one side is sometimes as distinctly a reply to the speech of the general on the other as if they had been dehvered in debate. We may be sure, however, that, wherever Thucydides had any authentic clue to the actual tenor of a speech, he preferred to follow that clue rather than to draw on his own invention.

“Why, however, did he not content himself with simply stating in his own person, the arguments and opinions which he conceived to have been prevalent? The question must be viewed from the standpoint of a Greek in the 5th century B.C. Epic poetry had then for many generations exercised a powerful intfuence over the Greek mind. Homer had accustomed Greeks to look for two elements in any complete expression of human energy-first, an account of a man's deeds then an image of his mind in the report of his words. The Homeric heroes are exhibited both in action and in speech. Further, the contemporary readers of Thucydides were men habituated to a civic life in which public speech played an allimportant part. Every adult citizen of a Greek democracy was a member ot the assembly which debated and decided great issues. The law courts the festlvals, the drama, the marketplace itself, ministered to the Greek love of animated description. To a Greek of that age a written history of political events would have seemed strangely insipid if speech "in the first person" had been absent from it especially it it did not offer some mirror of those debates which were inseparably associated with the central interests and the decisive moments of political life. In making historical persons say what they might have said, Thucydides confined that oratorical licence to the purpose which is its bes,t justification: with him it is strictly dramatic, an aid to the complete presentment of action, by the vivid expression ot ideas and arguments which were really current at the time. Among later historians who continued the practice Polybius, Sallust and Tacitus most resemble Thucydides in this particular; while in the Byzantine historians, as in some moderns who followed classical precedent, the speeches were usually mere occasions for rhetorical display. Botta's History of Italy from 1780 to 1814 affords one of the latest examples of the practice which was peculiarly suited to the Italian genius.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024