Home | Category: Minoans and Mycenaeans

MINOAN ART

The Minoans are widely admired today for their art. Minoan art is known of it imaginative images and exceptional workmanship. Sinclair Hood described an "essential quality of the finest Minoan art, the ability to create an atmosphere of movement and life although following a set of highly formal conventions".

The Minoans created pottery on hand-tuned wheels (2500 B.C.) and made earthen storage jars as tall as a man and thin shelled libation vessels decorated with starfish and sea shell motifs. Potters in Crete still make pottery using the same techniques as the Minoans. Some Minoan engravings of women give them strange robot-like heads. They also produced extraordinary rhytons (liquid-containing vessels) made to look like bulls heads.

The subject matter of Minoan artworks seems to have been heavily influenced by aesthetic considerations. Some have suggested that they may have loved art for its own sake, which would be an enormous change in the way art was traditionally created and used in other societies at that time. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: During the first half of the second millennium B.C. “great strides were made in metalworking and pottery—exquisite filigree, granulated jewelry, and carved seal stones reveal an extraordinary sensitivity to materials and dynamic forms. These characteristics are equally apparent in a variety of media, including clay, gold, stone, ivory, and bronze. [Source: Colette and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002 metmuseum.org \^/]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINOANS (3000-1400 B.C.): CRETE, HISTORY, ORIGIN, MYTHS, OTHER STATES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN SITES: CITIES, TOWNS, PALACES AND HILLTOP LABYRINTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN WRITING: LANGUAGES. HIEROGLYPHICS, LINEAR A europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN LIFE: SOCIETY, RELIGION, FOOD, BATHTUBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THERA ERUPTION: TSUNAMI, END OF THE MINOANS AND AKROTIRI europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Minoan and Mycenaean Art” by Reynold Higgins (1967) Amazon.com;

“The History of Minoan Pottery” by Philip Betancourt (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Bronze Age Begins: The Ceramics Revolution of Early Minoan I and the New Forms of Wealth that Transformed Prehistoric Society” by Philip P. Betancourt (2009) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Zoomorphic Culture: Between Bodies and Things” by Emily S. K. Anderson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Wall Painting of Pseira, Crete: A Goddess Worshipped in the Shrine” by Bernice Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

“Akrotiri: The Archaeological Site and the Museum of Prehistoric Thera. A Brief Guide”

by Christos Doumas (2017) Amazon.com;

“Thera: Pompeii of the Ancient Aegean : Excavations at Akrotiri 1967-1979"

by Christos G. Doumas (1983) Amazon.com;

“Akrotiri, Thera: An Architecture of Affluence 3,500 Years Old” by Clairy Palyvou (2016) Amazon.com;

“Akrotiri Santorini - A Biography of a Lost City” by Nanno Marinatos Amazon.com;

“Minoan Crete: An Introduction” by Livingston Vance Watrous (2020) Amazon.com;

“Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete” by Rodney Castleden (1990) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Civilization” by Stylianos Alexiou (1960) Amazon.com;

“The Minoans” by Ellen Adams (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age Illustrated Edition

by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean” (Oxford Handbooks) by Eric H. Cline Amazon.com;

“The Aegean Bronze Age” by Oliver Dickinson (Cambridge World Archaeology) (1994) Amazon.com;

“Greece in the Bronze Age” by Emily Vermeule (1964) Amazon.com;

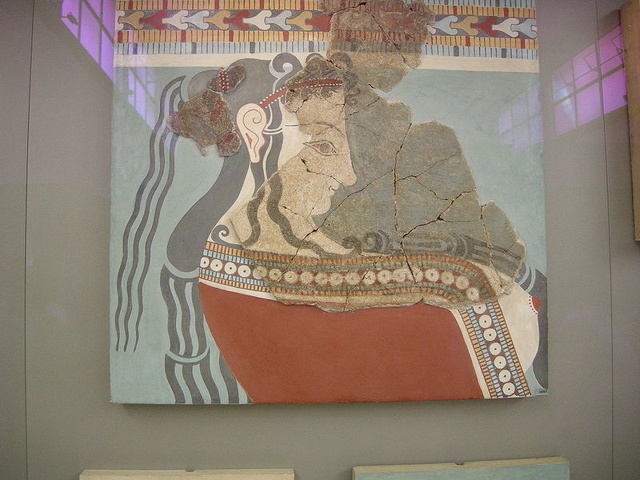

Minoan Painting

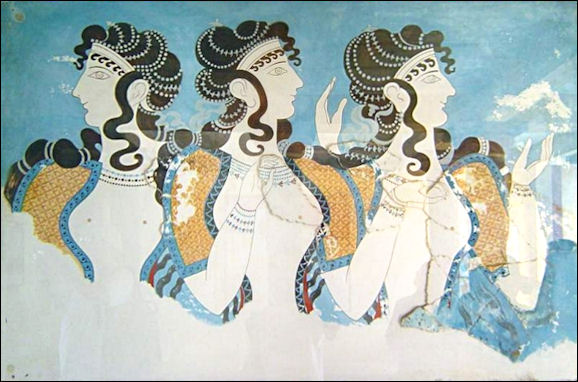

The Minoans produced lovely frescoes of dancers and bulls and made wild abstracts patterns on vases. Animals and sea creatures were commonly depicted in Minoan art. Octopuses strangled vases, dolphins leaped from murals, and mountain goats dashed across vessels. One mural fragment shows a cat stalking a pheasant from behind a bush. One scholar claimed that the Minoans had a "passion for rhythmic, undulating movement."

The walls and floors of Minoan palaces were often painted and sometimes featured colorful frescoes depicting rituals or scenes of nature. The palace at Knossos is where the famous leaping bull and dolphins frescoes were found. The earliest frescoes made walls and pavements were coated with a pale red derived from red ochre. Later white and black were added, and then blue, green, and yellow. The pigments were derived from natural materials, such as ground hematite. Outdoor panels were painted on fresh stucco. The indoor ones, with the motif in relief, were made on fresh, pure plaster, softer than the plaster with additives ordinarily used on walls.

The decorative motifs were generally bordered scenes: humans, legendary creatures, animals, rocks, vegetation, and marine life. The Grandstand Fresco appears to show a ceremony taking place in the Central Court at Knossos. In the Throne Room the throne is flanked by the Griffin Fresco, with two griffins lying down facing the throne, one on either side. Griffins were important mythological creatures, also appearing on seal rings.

Archaeological Museum of Heraklion

Archaeological Museum of Heraklion is one of the best museums in Greece and contains many of the world's Minoan artifacts. Among the museum’s treasures are ceramic polychrome vases found in the Kamares caves; marble vases encrusted with precious and semi-precious stones; sealstones carved out of semiprecious stones; gold ornaments; frescoes and sarcophagi. Particularly interesting are ceremonial axes and knives used in sacrifices; and libation jars used to collect the blood from the animals necks. Goats and bulls were the animals most commonly offered. Paintings on sarcophagi suggest that spotted bulls were the animals of choice. These same paintings show that the bull was tied down to a table and serenaded by a flutist while it bled.

The Minoans developed tools capable of cutting even the hardest stones. Among the items that had to have been produced with such tools are: a large lenticular sealstone, made of agate, depicting a goddess between griffins from Knossos and dated to 1450 - 1400 B.C.) In the New Palace period (1600-1450 B.C.) bronze work advanced and miniature bronze sculpture became relatively common. Animal figures, such as a seated wild goat, from Agia Triada, were typically smaller than the human ones. Unfortunately the most surviving examples of Minoan fresco paintings are fragmentary. The "Blue Bird", a fresco with a blue bird sitting on a rock among plants and flowers, was part of a larger composition from the "House of Frescoes" at Knossos, dated to the Neopalatial period (1550 - 1500 B.C.).

Vases depict men partying, shacking Egyptian rattles and singing so hard the ribs are pressed against their skin from lack of breath. A popular image was the bare breasted snake goddess with snakes crawling up her arms, around her head and tied into a knot about her waist. One of the unusual things about the worship of snakes by the Minoans is that Crete has virtually no snakes. Some miniature plaques show what Minoan houses looked like. There are also sculptures of dancers and bare-breasted maidens with snakes in their hands, vessels with starfish; massive knuckle covering gold rings with women with robot heads and frescoes of bull leapers.

Art at the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion

The Archaeological Museum of Heraklion contains more than 15,000 artifacts, spanning a period of 5,000 years, from the Neolithic era to Greco-Roman period, and collected from excavations carried out in all parts of Crete. The pieces include pottery in a variety of utilitarian yet imaginative shapes; stone carving of exceptional artistry; seal engraving; miniature sculpture; gold work; metalwork; household utensils; tools; weapons and sacred axes. The highlight is the frescoes, with their exquisitely-rendered figures and thoughtful, colorful compositions. [Source: Interkriti]

The pieces include: 1) a Libation vase (rhyton) of serpentine, in the shape of a bull's head with inlays of shell, rock crystal and jasper in the muzzle and eyes from Little Palace in Knossos and dated to 1600 - 1500 B.C.; 2) a flask decorated with a large octopus and supplementary motifs: sea urchins, seaweed and rocks from Palaikatsro (East Sitia) and dated to around 1400 B.C.; 3) a slender libation jug with spiky projections, decorated with painted papyrus flowers and nautilus from a grave at Katsambas (Iraklion) and dated to 1450-1400 B.C.; and 4) the famous "Harvesters' Vase", a steatite oval rhyton decorated with a relief procession of men returning from their work in the fields, from Agia Triada and dated to 1500 - 1450 B.C..

Examples of finely crafted metalwork include 1) a gold lion-shaped pendant from Agia Triada from the Post Palatial period (1450-1100 B.C.); 2) a silver pot (kylix) with gold plated handle and rim from a grave in Knossos area from the Final Palatial period (1450 - 1350 B.C.); 3) a bronze sword with gold-sheathed hilt and gold covered rivets, decorated with relief spirals from a cemetery in the Knossos area from the Final Palatial period (1450 - 1400 B.C.); and 4) a gold votive double axe with incised decorations from Arkalochori cave from the Early Neopalatial period (1700 - 1600 B.C.).

Building Delta and the Spring Fresco

Akrotiri Frescoes

The wall paintings of ancient Thera include the famous frescoes discovered by Spyridon Marinatos at the excavations of Akrotiri on the Greek island of Santorini (Thera). They are regarded as part of Minoan art, although the culture of Thera was somewhat different from that of Crete. They have the advantage of mostly being excavated in a more complete condition, still on their walls, than Minoan paintings from Knossos and other Cretan sites. [Source Wikipedia]

Most of the There frescos are now in the Prehistoric Museum of Thera on Santorini, or the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, which has several of the most complete and famous scenes. The Akrotiri frescoes feature a beautiful and vibrant range of colors, including reds, oranges, blues, blacks, and purples. Paints were made from crushed mineral powder and painted on wet or dry lime plaster that had been applied to a wall. The chemical process of carbonation — in which plaster dried and the lime reacts with carbon dioxide in the air — fixed the pigment to the plaster. An organic fixative was sometimes applied to the painted plaster ensure the colours did not fade. [Source Archaeology Travel]

Subject matter in Akrotiri frescoes included animals, plants, fish and marine themes. Among the images of mammals and birds and mythological creatures are bulls, antelopes, monkeys, ducks, swallows and griffins. Geometric and abstract shapes are also common, sometimes on paintings with animals and people Fragments of frescoes has been found in many different types of buildings in Akrotiri. This suggests that this kind of art was not restricted to an elite class, but enjoyed by all. The exceptional preservation of the frescoes, like those at Pompeii, is largely a result of the buildings having been covered with volcanic ash.

The “Building Delta and the Spring Fresco” at the Thera Gallery at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens is the only wall painting from Akrotiri that was found in situ. Covering three walls of a single room, it was found below a shelf in a room with a plaster cast of a bed and depicts volcanic landscape with flowers in different stages of blooming. Swallows are portrayed. in flight. To many the flowers and birds are evocative spring, hence the name.

A room in another building in the the National Archaeological Museum in Athens features a pair of young boys boxing with a pair of antelope on the adjacent wall. Running around the room, above the friezes is decorative ivy. The two naked boys seen boxing are more likely engaged in ritual sport rather than competition. The boys wear loin cloths, only one glove, and jewellery. Although simple drawn using thick black lines on a white background, the two antelope are highly expressive in their movements.

Monkeys of Akrotiri

Akrotiri was a Bronze Age Minoan settlement on Santorini that was destroyed and buried Pompeii-style by the massive Thera volcanic eruption sometime in the 16th century B.C. A number of beautiful frescoes have been found there. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Scholars have longed believed that a Bronze Age Aegean painting of a troop of monkeys depicts stylized exotic primates cavorting about a rocky landscape. The fresco adorns a room in a two-story complex at the second-millennium B.C. settlement of Akrotiri on the Greek island of Thera. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2020]

No monkeys are native to the region, and the depictions were thought to have been made by painters following Egyptian stylistic conventions, which often rendered animal species as abstract types. Now, a team led by University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Marie Nicole Pareja that includes primatologists and a taxonomic illustrator has concluded that the Akrotiri monkeys are, in fact, accurate depictions of langur monkeys, whose natural range is the Indus River Valley, some 4,000 miles away.

“The researchers observed that the Akrotiri monkeys have S- or C-shaped tails, just as langurs do. Pareja believes this key detail shows that the artists who created the fresco must have seen the primates with their own eyes. “We think they had direct contact with the langurs,” says Pareja. “Textual sources suggest Mesopotamians imported critters from the Indus Valley, so it’s possible the painters encountered the langurs there, or elsewhere in the Near East.”

Minoans Invented Purple Dye Production

For more than 2,000 years, historical sources have credited the discovery of purple-dye production to the Phoenicians. Sara Toth Stub wrote in Archaeology magazine: According to a second-century A.D. account from the Greek historian Julius Pollux, a dog belonging to the Phoenician king Heracles of Tyre accidentally discovered the dye’s source by biting on a seashell. In fact, the word “Phoenician,” a moniker first bestowed by the Greeks, means purple. [Source: Sara Toth Stub, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

Despite the long-standing association between the Phoenicians and murex dye, however, scholars believe they probably were not the first to develop it. Instead, evidence increasingly points to the island of Crete as its origin. There, from about 3000 B.C. until the mid-fifteenth century B.C., the Minoans established extensive maritime trade networks around the Aegean. Ancient tablets from the Minoan palace at Knossos refer to the royal use of purple textiles.

fresco of women

In 2016, chemical analysis of residue in stone vats and vessels from a Minoan-era dye installation on the nearby island of Pefka identified biomarkers of murex snails, along with lanolin, which was used to prepare raw wool for dyeing. This indicates that as far back as 1800 B.C. — at least 300 years before the rise of the Phoenicians — people there colored textiles using murex dye. Andrew Koh, an archaeologist and historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who conducted residue analysis of pottery and stone dyeing installations from Pefka, says the rugged shorelines of Crete and nearby islands were especially suitable for murex snails, which thrive along shallow, rocky coastlines. “In terms of pure numbers [of snails] and ecological conditions,” he says, “chances are this industry was invented in Greece.”

“Other cultures, including the Phoenicians, eventually learned of the murex dyeing technique through trade relations, Koh suggests, and he and Gilboa agree that the Phoenicians likely improved on the Minoans’ techniques and expanded the dye’s reach. Says Koh, “It’s clear that by the eighth century, the Phoenicians have the hold on this industry.”

Royal Purple

The purple dye produced from Murex sea snails was a precious rarity in the Bronze Age Mediterranean region, bioarchaeologist Deborah Ruscillo of Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri told Live Science. Ruscillo has studied the production of the ancient purple dye, including experimenting with it to make colors from pink to blue to almost black, though she isn't involved in the excavations on Chrysi. "Purple did not exist from any other source at the time," she told Live Science. "Cheaper plant substitutes, such as madder or woad, did not come around until the Middle Ages, so until that time Murex purple was the only source." [Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, December 11, 2019]

According to Live Science: The shellfish make a small amount of the purple substance inside their bodies, and use it as a poisonous defense against predators. It takes thousands of Murex sea snails to produce enough purple dye to color a single garment, a difficult and sometimes dangerous task. "There was danger and discomfort involved in harvesting the snails from the sea, strength required to break open the shells, [and] the smell was horrendous," she said.

The difficulty of making the dye led to it only being used by the wealthy and royal, and it became known as "Royal purple." It was also known as "Tyrian purple," after the ancient Phoenican coastal city of Tyre, a source of the dye; and it's thought to be the Tekhelet dye described in Hebrew scriptures as the color of the curtains of the tabernacle and the vestments of the high priest, Ruscillo said.

Later in history, the use of the rare and expensive color purple was restricted by Roman sumptuary laws, which penalized ostentatious clothing and jewelry. Eventually, the color purple became a signifier of the Roman emperor: The ascension of a new emperor became known as "donning the purple," and children of the Imperial family were said to be "born into the purple."

Tiny Minoan Island Devoted to Making the Color Purple

In 2019, archaeologists announced they had discovered an ancient building on the small, now-uninhabited island of Chrysi used by purple dye-makers between 3500 and 3800 years ago during the Protopalatial and Neopalatial periods of the Minoan civilization on Crete. The finds on Chrysi show the high value placed on the rare purple dye at a very early date. Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Archaeologists think the largest building in the settlement was inhabited by a local elite who may have governed the Minoan settlement on the tiny island, south of the east end of Crete, Greece's culture ministry said in a statement.[Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, December 11, 2019]

The team found deep beds of thousands of the shells of spiny sea snails called Murex — which make the vivid purple substance within their bodies — in several small buildings in the settlement but not in the large building. Instead, the large building was equipped with terraces, work desks, stoves, buckets and a stone staircase, suggesting that it was once inhabited by those who managed the settlement's production of the purple dye, and perhaps its promotion and trade to buyers who visited the island by ship, as well as payments wherein precious metals, jewelry and gemstones.

Based on their earlier work, the scientists suspect that the tanks were used to farm the shellfish — a species of Murex called Hexaplex trunculus — to increase their numbers and reduce the labor of harvesting them from the sea. The tanks were also supplied with extra seawater from a cistern, the regional director of antiquities and leader of the excavations, Chryssa Sofianou, told Live Science. "We think the shellfish were cultivated."

Archaeologists have investigated the settlement on Chrysi since 2008, revealing various discoveries, including the remains of large carved stone tanks near the waterline on the beach. The most recent excavations have centered on the largest of the several ancient buildings in the settlement, where the archaeologists found ancient artifacts, including wa ring, a bracelet and 26 beads made from gold. They also discovered beads made from silver, bronze and glass; and semiprecious gemstones, including amethyst and lapis lazuli. The researchers also found a seal made from agate, adorned with a carving of a ship; three large vases made of copper; and ingots of bronze and tin — one of the largest caches of raw metal ever found in Crete.

Sofianou said it was not possible yet to say just how many people lived at the settlement, but that was one of the questions that archaeologists sought to answer. Although the purple-making settlement on Chrysi is old, it's not quite the earliest found on Crete. Archaeologists think the Minoans may have been the first to make the famous dye about 4,000 years ago.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024