Home | Category: Minoans and Mycenaeans

THERA ERUPTION

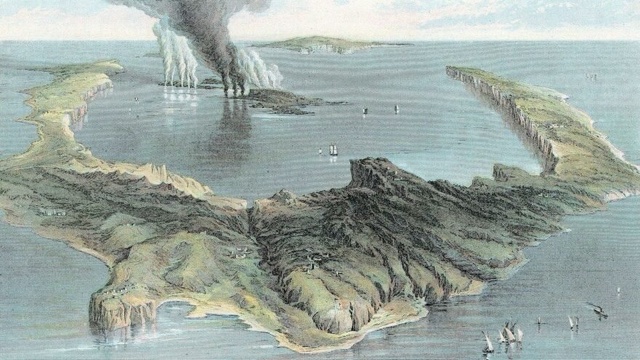

Thera In the 17th century B.C., a volcano on Santorini erupted with such force that some believe it caused the collapse of the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete, 70 miles away. Thirteen cubic miles of material exploded into the sky. Settlements on Santorini were buried under a thick layer of ash thicker than the one that covered Pompeii. The explosion, estimated to be approximately 100 times more powerful than the eruption at Pompeii, blew out the interior of the island and forever altered its topography. Possibly as many as 20,000 people were killed as a result of the volcanic explosion. [Source: Canadian Museum of History , William Broad, New York Times, October 21, 2003]

The “super-colossal” eruption of Thera has been categorized as a 7 (out of 8) on the volcanic explosivity index and been equated with the detonation of millions of Hiroshima-type atomic bombs. Some scholars believe the traumatic collective memory of the event gave birth to Plato’s allegory of the sunken city of Atlantis, composed more than a thousand years later, and may havee even been reflected in the biblical Ten Plagues. [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, July 14, 2023]

The main eruption was preceded by a smaller one — a shower of light pumice that buried the town of Akrortiri, down slope, under many feet of ash. This may have sent most of the residents away. No skeletons or human remains have been found on Santorini. The main eruption began when sea water entered a vent of the volcano and mixed with magma and gases, producing an ultra-violent explosion. The center of Thera collapsed into a sea-filled caldera. Santorini was buried Pompeii-style under ash, up to 900 feet deep, that preserved frescoes and wall paintings that recorded everyday life from the period and contained Egyptian motifs.

The explosion produced a huge tsunami, possibly a 100 meters (300 feet) high. This tsunami swamped and hit the coast of North Africa, sending water 330 kilometers (200 miles) up the Nile. On Crete, an 50-foot-high tsunami wiped out coastal settlements. Inland ash may have ruined crops and grass that fed livestock.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINOANS (3000-1400 B.C.): CRETE, HISTORY, ORIGIN, MYTHS, OTHER STATES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN SITES: CITIES, TOWNS, PALACES AND HILLTOP LABYRINTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN WRITING: LANGUAGES. HIEROGLYPHICS, LINEAR A europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN LIFE: SOCIETY, RELIGION, FOOD, BATHTUBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN CULTURE: ART, FRESCOES AND THE COLOR PURPLE europe.factsanddetails.com

Good Archaeology Websites Aegean Prehistoric Archaeology sites.dartmouth.edu; Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/ ; Websites on Ancient Greece: British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Eruption of Ancient Thera and its Effects on Mediterranean Civilizations of the Middle Bronze Age” by Melissa Lykins (2024) Amazon.com;

“Miletos: Archaeology and History” by Alan M. Greaves (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Troubled Island: Minoan Crete Before and After the Santorini Eruption” (Aegaeum)

by J Driessen and Cf MacDonald (2020) Amazon.com;

“Fire in the Sea: The Santorini Volcano: Natural History and the Legend of Atlantis” by by Walter L. Friedrich, Alexander R. McBirney (2000) Amazon.com;

“Akrotiri: The Archaeological Site and the Museum of Prehistoric Thera. A Brief Guide”

by Christos Doumas (2017) Amazon.com;

“Thera: Pompeii of the Ancient Aegean : Excavations at Akrotiri 1967-1979"

by Christos G. Doumas (1983) Amazon.com;

“Akrotiri, Thera: An Architecture of Affluence 3,500 Years Old” by Clairy Palyvou (2016) Amazon.com;

"Akrotiri Santorini - A Biography of a Lost City” by Nanno Marinatos Amazon.com;

“Minoan Crete: An Introduction” by Livingston Vance Watrous (2020) Amazon.com;

“Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete” by Rodney Castleden (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Destruction of Knossos: The Rise and Fall of Minoan Crete” by H. E. L. Mellersh (1970) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age Illustrated Edition

by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean” (Oxford Handbooks) by Eric H. Cline Amazon.com;

“The Aegean Bronze Age” by Oliver Dickinson (Cambridge World Archaeology) (1994) Amazon.com;

Killer Tsunamis From Thera

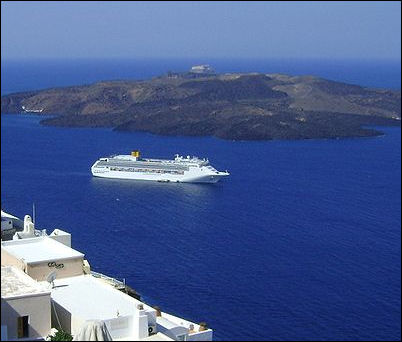

Thera from Santorini

The massive eruption of the Thera volcano produced tsunamis that tore across hundreds of kilometers of the Eastern Mediterranean to inundate the area that is now Israel and probably other coastal sites, a team of scientists reported in the October 2009 issue of Geology. William J. Broad wrote in New York Times: Geologists judge the eruption as far more violent than the 1883 eruption of the volcanic island of Krakatoa in Indonesia, which killed more than 36,000.

The team did its excavations off Caesarea, Israel, a coastal town dating from Roman and Byzantine days. The coastal region was only sparsely settled at the time of the Thera eruption, with no identifiable city. [Source: William J. Broad, New York Times, November 2, 2009]

“The team sank a half-dozen tubes into the offshore seabed and pulled up sediment cores for analysis. It looked for standard signs of tsunami upheaval, including pumice (the volcanic rock that solidifies from frothy lava), distinctive patterns of microfossils, cultural materials from human dwellings and well-rounded beach pebbles that seldom appear in deeper waters. Writing in Geology, a journal published by the Geological Society of America, the team reported finding evidence of three tsunamis — two historically documented ones dating to A.D. 115 and 551, and one from the time of the Thera eruption.

“The Thera tsunamis, the team wrote, left a signature layer in the seabed of well-rounded pebbles, distinctive patterns of mollusks and characteristic inclusions in rocky fragments all oriented in the same direction. The disturbed layer, up to 16 inches wide, came from a few feet below the seabed in waters up to 65 feet deep. “These findings,” the team wrote, “constitute the most comprehensive evidence to date that the tsunami event precipitated by the eruption of Santorini reached the maximum extent of the Eastern Mediterranean.” The team added that, if the giant waves were big enough to reach Israel, “then presumably other Late Bronze Age coastal sites across the Eastern Mediterranean littoral will likely have been affected as well.”

Impact of Thera Eruption on the Eastern Mediterranean

The Thera eruption had a dramatic affect on the eastern Mediterranean that lasted for decades, even centuries. Dense clouds of volcanic ash and deadly tsunamis were generated over a huge area, crippling ancient cities and fleets, setting off climate changes, and sowing political unrest. There are no firsthand accounts of the eruption and tsunami, but modern researchers have made great strides in defining its scope and the impact it had on the cultures and people of the Mediterranean, especially the Minoans. [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, July 14, 2023]

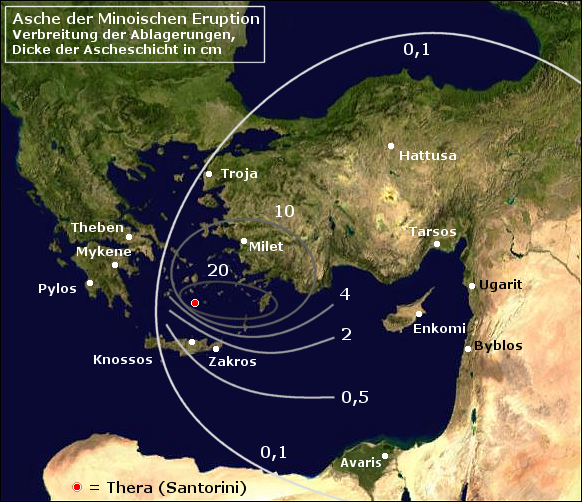

The Thera eruption produced two large ash clouds. One that was blown by lower atmosphere winds to the southeast towards Crete and Egypt and another that was blown by the jet stream in the stratosphere to the northeast over Anatolia (Turkey). Dr. Peter Kuniholm, a tree ring expert at Cornell, found that trees found in an Anatolian burial mound grew three times faster that normal for about half a decade around the time of eruption, presumably because the ash turned the region’s normally hot, dry summers into ones that were unusually cool and wet.

But although the ash seems to have helped trees it is thought it severely damaged wheat fields and reduced harvests. Many think it was the primary factor behind Mursilis, king of the Hittites, setting out from his Anatolian kingdom and attacking Syria and Babylon, which lay between the two plumes, and seizing their stored grains and cereals. This in turn prodded Babylon towards collapse and hurt one of its allies, the Hyksos, who ruled Egypt and traded with the Minoans.

The plagues described in the Bible are thought by some to be a result of the Thera volcano. The explosion and land submerged by the tsunami may be the source of Plato’s story of Atlantis. Some scholars speculate that ancient Minoa or Thera may were have been Atlantis, which Plato, supposedly heard about from Socrates who in turn heard about it from Egyptians. Some historians believe the Thera eruption changed the entire coarse of history. With Minoans out of the picture, they hypothesize, cultures on the Balkan peninsula were able to develop into classical Greece.

Santorini Caldera produced by the Thera eruption

According to the BBC: The cataclysmic Thera eruption happened 100 kilometers from the island of Crete, the home of the Minoans. Fifty years after the eruption, that civilisation was gone. Did the volcano wipe out the Minoans and if it did what exactly took place? Jessica Cecil wrote for the BBC: “Early 20th-century archaeologists knew of the devastating volcano and some concluded it must have snuffed out the Minoan civilisation almost instantly. But was it really as simple as that? For a start, they discovered little ash had fallen on Crete - as luck would have it, the prevailing winds took the volcano's ash in the opposite direction. Then archaeologists found clay tablets that proved the Minoan civilisation survived for about 50 years after the eruption. So if the volcano killed the civilisation, what accounted for this long gap? [Source: Jessica Cecil, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Did the Thera Volcano and Tsunami Cause the End of Minoa?

The Thera eruption may have been the largest eruption on Earth in the last 10,000 years. Some scientists have calculated was 90 times greater than the one at Mount St. Helens and four times greater than Krakatau, which killed 36,000 people . Some say it was much larger than that, perhaps even larger than Tambora, which erupted in 1816 and produced the year without summer and famines in the United States.

After the Thera eruption 50 foot tsunamis smashed against Crete’s shores, smashing ports and fleets and severely damaging in the maritime economy, which was vital for the Minoans as it was an island civilization. Ash levels of 10 feet were recorded 20 miles away on the island Anafi. That was incredible amount of ash that distance away.

In 1939 Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos theorized that eruption of Thera caused the collapse of Minoan civilization with damaging earthquakes and tsunamis. Some doubts were raised about earthquake side of the story because earthquakes associated with volcanic eruptions are usually not that strong. In the mid 1960s scientists dredging up sediments found thick layers of ash linked to Thera’s eruption and found it covered thousands of square miles.

But the theory was given a blow in 1987 when the date of the eruption was set at 1645 B.C. based in the presence of frozen ash in Greenland ice cores, 150 year before the pervious dates, and 200 years before the steep decline of Minoan culture. The theory was given another blow in 1989 when a Minoan house was found built above the ash layer.

Now the reasoning goes the eruption took time to bring down Minoa. Some archaeologists say the eruption and tidal waves did not destroy Minoa rather it weakened, making it vulnerable to conquest. An the Mycenaeans were the ones who conquered it. They theorize the that ash from the eruption could have destroyed crops, brought about a famine, opening the way for a conquest from the Mycenaeans.

A century earlier a large earthquake destroyed the palace of Knossos. It was rebuilt. An earthquake that occurred around the time of the Thera explosion damaged the palace. In the decades that followed all the major palaces of Crete were damaged by fire, most likely by invaders.

Ash from the Thera eruption

By 1450 B.C. nearly all Minoan palace-cities, except Knossos were mysteriously destroyed. Around this time pottery styles and writing styles changed reflecting styles introduced from Mycenae, suggesting that the Mycenaeans took over Crete. By the 14th century B.C., Knossos appeared to be under the administration of the Mycenaeans.

Tsunami Destruction and the Massive Size of the Thera Eruption

Jessica Cecil wrote for the BBC: Vulcanologist Floyd McCoy from the University of Hawaii “was convinced that giant waves, or tsunamis, had been unleashed by the volcano. He believed these waves travelled across the open sea to batter the northern coast of Crete - but proof was hard to find. In 1997 a young British geologist, Dr Dale Dominey-Howes of Kingston University, found what he believes is firm evidence of tsunamis on Crete. He drilled deep into the mud at an inland marsh near Malia in Crete, and took the mud core he found back to England for analysis. |[Source: Jessica Cecil, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The mud had been deposited, layer upon layer, over thousands of years. At one place, deep in the core, Dr Dominey-Howes found a type of tiny fossilised shell that only lives in very deep sea water. He felt sure the shells were brought into the marsh by an ancient tsunami. A Minoan palace near the marsh was buried at the same level as the shells, suggesting the tsunami could have hit soon after the palace was built. |::|

“If a tsunami had been unleashed by the eruption of Thera, Floyd McCoy wanted to know how big it might have been. He turned to Professor Costas Synolakis of the University of Southern California...one of the world's top predictors of tsunamis... He estimated that waves from Thera battering northern Crete could have been up to 12 meters high in places. Such waves would have destroyed boats and coastal villages, even travelling up rivers to flood farmland. |::|

“But however terrifying these waves, they can only have been part of the story. McCoy was convinced the volcano must have had wider effects. A remarkable discovery by a British geologist gave rise to a new theory - that the volcano already classed as one of the most devastating of the last 10,000 years could have been even bigger than scientists had previously thought. |::|

“Professor Steve Sparks of Bristol University found clues in the smallest fragments of evidence. He was surprised to find clumps of fossilised algae high on the cliffs of the volcano. These algae only live in shallow waters, and their presence suggested there was once a shallow sea inside the crater of the volcano. If there had been a shallow sea, Professor Sparks realised, the shape of the volcano could have been entirely different, and a differently shaped volcano could have produced far more ash. His hunch was that the volcano could have been twice as powerful as geologists had suspected.” |::|

Nile delta's elevation cross section shows how vulnerable it is to a tsunami

Cycle of Disaster Following the Thera Eruption

Jessica Cecil wrote for the BBC: “What might a volcano of this size have meant for the Minoans on Crete? Volcanoes throw up sulphur dioxide, and huge amounts of this gas can alter the climate. Climate modeller Mike Rampino at New York University calculated that the eruption on Thera could have lowered annual average temperatures by one to two degrees across Europe, Asia and North America. Rampino believes the summer temperatures would have dropped even more, suggesting years of cold, wet summers and ruined harvests. [Source: Jessica Cecil, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Rampino's calculations were supported by the work of Professor Mike Baillie of the Queen's University, Belfast. Ancient logs preserved for millennia in Irish bogs contain a record of the weather - and especially the cold, wet periods that stunt trees' growth. Trees that were growing at the time of the eruption - 3,500 years ago - show signs that the climate was especially wet and cold then. |::|

“Floyd McCoy believes the volcano undermined the Minoans for years. First, it destroyed an entire island that had been crucial to their trade. Then, giant waves battered the Minoan coasts, destroying coastal villages and boats at harbour. Next, the Minoans faced summers of ruined harvests. |::|

“Knossos archaeologist Colin MacDonald thinks the effects of these disasters were compounded by something more - the Minoans began to see their world in a different way. MacDonald believes the Minoan people, stripped of their certainties, stopped obeying the priest kings in palaces like Knossos. This marked the start of a 50-year decline for the entire Minoan civilisation. They were in no position to fight back when Greeks from the mainland took control of the island.” |::|

End of the Minoans

Around 1450 B.C. the Minoan civilization, which appears to have been peaceful and prosperous, came to an abrupt and probably violent end. There is evidence of wholesale destruction by fire and there has long been speculation that a volcanic explosion at Thera (followed possibly by a tsunami) created s April 5, 2006 great civilization of the Aegean world. That hypothesis has now been called into question as recent studies of ice core samples push the Thera eruption further into the past. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “From 1500 B.C., there was increasing influence from the Mycenaean culture on the Greek mainland, and there is clear archaeological evidence for widespread destruction on the island around 1450 B.C. If the Mycenaeans were not responsible for this destruction, they certainly took advantage of the events—administrative records from this period are written in Linear B, the script of Mycenaean Greeks. Contemporary pottery shows a blend of Minoan and Mycenaean stylistic traits. Eventually, by the beginning of the eleventh century B.C., the Minoan culture on Crete was in decline.” [Source: Colette and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002 metmuseum.org \^/]

Dating the Thera Eruption

Historians have been debating for years about exactly when the major eruption at Thera took place. Radio-carbon dating and dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) had narrowed the date down to a range of years but neither could confirm a specific year. Then improvements in the science of ice core dating made it possible to pinpoint a particular year-1646 B.C. - a century earlier than most historians had thought. (Ice cores drilled out of the Greenland ice cap show seasonal variation in the same manner as tree rings. The winter snow fall creates yearly bands and within that band the atmospheric activity is recorded. The volcanic eruption at Thera was confirmed as happening in 1646. At the present time, the core depth allows scholars to look back in time some 200,000 years and work will continue on making that timeline longer.)” |

Kristin Romey wrote in National Geographic: Traditionally the eruption of Thera has been assigned to a time period known as Late Minoan IA, which is associated with Egypt’s 18th dynasty in the 1500s B.C. But radiocarbon dates of wood found in ash layers at Akrotiri date to the mid-late 1600s B.C.—a discrepancy of up to more than a century. This causes problems for researchers trying to correlate relative chronologies of the different cultures that lived around the Mediterranean at the time and how they interacted before and after the disaster.

According to the researchers, the eruption could not have occurred earlier than the earliest date they obtained from within the tsunami deposit at Çesme-Bağlararası—a grain of barley found near the remains of the young man, radiocarbon dated to 1612 B.C. Radiocarbon dates for other materials are currently in progress.

Evidence of the Tsunami from Thera Eruption

In a paper published in late 2021 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, an international team of researchers presented evidence of a destructive tsunami that followed the eruption of Thera. Thera paper describes research at the archaeological site of Çesme-Bağlararası, located in the popular resort town of Çesme on Turkey’s Aegean coast and more than 160 kilometers (100 miles) north-northeast of Santorini. [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, July 14, 2023]

Kristin Romey wrote in National Geographic: Since 2009, archaeologist Vasıf Şahoğlu of Turkey’s Ankara University has directed excavations at what seemed to be a thriving coastal settlement occupied almost continuously from the mid third millennium to the 13th century B.C. But unlike the well-preserved buildings and roads from earlier phases of the site, Şahoğlu focused on an area where he quickly dug into chaos: collapsed walls, layers of ash, and jumbles of pottery, bone, and marine shells. He reached out to colleagues in various specialties who could help make sense of the mess, including Beverly Goodman-Tchernov, a professor of marine geosciences at Israel’s University of Haifa and National Geographic Explorer who has a particular focus on identifying tsunamis in the archaeological and geological records.

Signatures of past tsunamis may be difficult to identify—evidence such as collapsed buildings and fires may also be the result of earthquakes, floods, or storms. Even then, such evidence can fade quickly with time, particularly in more arid environments like the Aegean coast. While the impacts of the Thera eruption can be seen far away, in Greenland’s ice sheets and California’s bristlecone pines, only six physical sites with evidence for the Thera-driven tsunami that thundered through the Aegean have been identified so far, and none with the complexity provided by Çesme-Bağlararası.

“Tsunami are predominantly erosive events … not depositional events, thus the excitement when we find them!” says Floyd McCoy, a professor of geology and oceanography at the University of Hawaii, Windward College. McCoy, a National Geographic Explorer who has studied the Thera eruption and tsunami event but did not participate in the new project, calls the research “a real contribution not only to research on tsunami deposits but on their meaning and interpretation especially related to the [Bronze Age] eruption of Thera.”

Now researchers are creating increasingly sophisticated “checklists” to look for historical tsunami events, which also include physical and chemical signatures for marine life brought onto land with the inundating waves, and the particular patterning of sediment and rock deposits. At Çeşme-Bağlararası, for instance, mats of shellfish carried in from the ocean were found wedged against collapsed walls of buildings.

“It’s rare that I feel really confident in tsunami interpretation, especially in an arid environment, because you just don't have a lot of stuff to work with,” says Jessica Pilarczyk, an assistant professor of earth sciences and Canada research chair in natural hazards at Simon Fraser University, who did not participate in the Çesme-Bağlararası research. “But it seems in this case, there's some really great evidence that they were able to capture and process.”

Why So Little Evidence of Victims from Thera Eruption-Tsunami

As we said earlier possibly as many as 20,000 people were killed as a result of the volcanic explosion at Thera and the subsequent tsunami but surprisingly almost no evidence of victims has been found. Until the 2020s, only one individual has been identified as a possible victim of Thera: a man found buried under rubble on the Santorini during investigations in the late 19th century.

According to Archaeology magazine: A teenager and a dog buried in destruction layers at the settlement of Çesme-Baglararası are believed to be the first victims of the eruption of Thera ever discovered. The catastrophic explosion on the present-day island of Santorini, 85 kilometers (140 miles) away, triggered tsunamis that destroyed the coastal Bronze Age settlement. Evidence shows that survivors attempted to dig through the rubble to rescue those trapped — they only missed locating the young man and canine by about one meter (3 feet). [Source: Archaeology magazine, March 2022]

Kristin Romey wrote in National Geographic: One of the most puzzling aspects of the Thera eruption is the lack of victims: more than 35,000 people are estimated to have died in the tsunami spurred by the Krakatoa eruption, and similar numbers have been proposed for the Bronze Age Aegean. [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, July 14, 2023]

Theories about the lack of victims vary: smaller, earlier eruptions led people to flee the area before the cataclysmic eruption occurred; victims were incinerated by super-heated gases, or perished mainly in the sea, or were buried in mass graves that have yet to be identified. “How does one of the worst natural disasters in history have no victims?” Şahoğlu asks.

Goodman-Tchernov suspects that, just as researchers may have been unable to recognize tsunami deposits in the past, they may have also already uncovered victims from the Thera disaster but failed to make the connection. In Çesme-Bağlararası, however, the researchers say they have almost certainly found a victim of the event: the skeletal remains of a young, healthy man with signs of blunt force trauma, found prone in the rubble of the tsunami deposit.

Tsunamis in Çesme-Bağlararası

Kristin Romey wrote in National Geographic: The researchers determined that four waves of tsunami landfalls hit Çesme-Bağlararası over the course of a few days or weeks. This is particularly fascinating to McCoy, who notes that there were four phases to the eruption of Thera; researchers have long wondered which eruption phase triggered what they thought was a single tsunami event. [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, July 14, 2023]

map of Akrotiri

As the waters receded between tsunami landfalls, it appears that surviving residents took the opportunity to dig into the chaos in search victims and of building materials. One such pit was found directly above the body of the young man; whoever dug it, however, stopped a few feet too soon to retrieve him. This evidence of attempting to retrieve tsunami victims suggests concern about adequate burial after the disaster, possibly in mass graves to reduce disease in its aftermath.

Evidence for a more recent tsunami that struck the eastern Mediterranean—some 2,300 years after the Thera event—appears in the the journal Geosciences. Goodman-Tchernov and her colleague C.J. Everhardt of the University of Haifa describe how an earthquake on the inland Dead Sea fault sparked destructive waves that damaged the ancient port of Caesarea Maritima on the coast of what is now Israel in 749 A.D.

Evidence comes from a harbor warehouse that was destroyed in the the event; the distinctive, chaotic signature of a tsunami was preserved by later building activity at the site. Less than a few dozen coastal archaeological sites worldwide have reported tsunami deposits, making this study unique, Goodman-Tchernov says. "We really only have about a century of instrumental records on tsunamis, and maybe 20-30 years of refined satellite data, so in a lot of ways we effectively don't know everything that happens during a tsunami." The geoscientist adds that the increasing loss of natural coastline buffers combined with more people living on coasts is making us only more vulnerable. "A tsunami that happened 100 years ago is going to be much less dangerous than a tsunami that happens today."

Akrotiri: the Minoan Pompei

Akrotiri was a Bronze Age Minoan settlement on Santorini that was destroyed by the massive Thera volcanic eruption sometime in the 16th century BC. The city was completely buried in volcanic ash, which preserved the remains of fine frescoes and many other artworks and objects, much like what occurred later in the city of Pompeii, near Italy’s Mt. Vesuvius.

Akrotiri is located outside of Fira on Santorini. The leader of an early excavation there died in 1974 when he fell in one of the excavations and hit his head. Relatively few artifacts have been found which means the people had a chance to flee before the volcano catastrophically erupted. Only a small area has been excavated from the hardened volcanic ash, revealing houses with that are now in the Athens Archeological Museum. Just as happened at Pompeii centuries later, a settlement on Thera known as the town of Akrotiri was buried under a thick blanket of ash and pumice. For more than 3,500 years the ancient Bronze Age community lay hidden- one of Greece's many secrets of the past. Then, as is often the case with various heritage sites, the town of Akrotiri was accidentally discovered. Quarry workers, digging out the pumice for use in the manufacture of cement for the Suez Canal, chanced upon some stone walls in the middle of their quarry.

Akatoriki excavation

These eventually proved to be remains of the long-forgotten town. Archaeologists from France and later from Germany did some preliminary excavation in the second half of the 19th Century but it was not until 1967 that systematic excavation began at the site in earnest. Spyridon Marinatos, supported by the Archaeological Society of Athens, soon began to uncover the remains of the ancient town. It was not easy. Not only were the buried buildings two or even three stories tall, the original building materials (clay and wood) had been damaged by earthquakes, fire and the hands of time. It was necessary to proceed slowly and carefully. Work on the project has now been on-going for almost four decades and it is likely to continue into the foreseeable future.

“The site has yielded some surprising information. Most startling of all is the fact that no human remains have been found at Akrotiri, unlike Pompeii and Herculaneum where the dead were buried in the midst of their daily activities. At Akrotiri, it was obvious that people had begun to do some repair work to their dwellings, probably in response to minor earthquake or volcanic damage. However, before the major eruption at least some of them had the time to pack up their families and most valuable possessions and leave. Huge pottery containers and large household furnishings were abandoned in their haste to depart but it seems clear that most people got away safely, were buried elsewhere or were swept away by the tsunami waves that might have accompanied such a massive eruption." |

Jessica Cecil wrote in for the BBC: “Akrotiri's chief archaeologist, Christos Doumas, believes the people of Akrotiri didn't survive, and that the bodies are still to be uncovered, huddled at the harbour where they were trapped by the eruption as they waited to escape. He believes it's highly unlikely that scores of boats were waiting in the harbour to save them. [Source: Jessica Cecil, BBC, February 17, 2011]

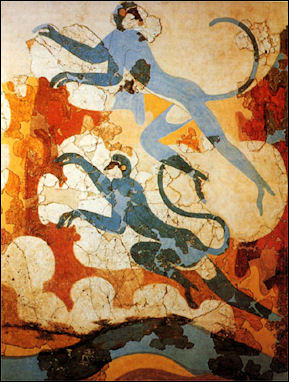

“The Akrotiri site has not yielded huge amounts of gold, silver and bronze artifacts, nothing on the scale that might have been expected had the inhabitants been caught unawares. But a splendid visual legacy was left, most of it in pieces that are painstakingly being assembled by Christos Doumas and his colleagues. The frescoes at Akrotiri are spectacular, were exceptionally well-preserved by the protective blanket of ash that covered them and their locations can be correlated to various rooms within the town.

The paintings provide a lot of visual information that needs to be carefully analyzed- a fleet of ships manned by sailors allowing one to see how the vessels were rigged, how the crew was dressed, what they carried by way of tools and weapons; people in the community going about their daily activities, picking flowers, making religious offerings; two nude fishermen carrying strings of fish; young boys in a boxing match, etc.” |

Discoveries from Akrotiri

Akrotiri blue monkeys

In early 2020, archaeologists revealed significant new findings found during ongoing excavations at the archaeological site of Akrotiri, the Ministry of Culture of Greece announced. According to the Greek Reporter: Most of the discoveries are related to the everyday life of the people who lived on the island before the volcanic explosion which destroyed most of the island. [Source Greek Reporter, January 31, 2020]

Ordinary objects used by the people of the island, even including clothing and burned fruit, were found, most likely believed to be the very last objects the people of Santorini were using in the moments before the devastating volcanic eruption. Additionally, more than 130 micelle vessels were found, which archaeologists believe were most likely related to a burial place.

The archaeological dig on Santorini is taking place under the auspices of the Greek Archaeological Society and under the direction of Professor Christos Doumas. The statement from the Ministry of Culture informs the public that among the new discoveries are ”four vessels, partially discovered in earlier excavations.” Other findings include bronze objects, including two large double braids and miniature horn cores, as well as small fragments and beads from one or more necklaces. Among dozens of other new findings, the Ministry of Culture noted that an inscription, consisting of Linear A syllables and an ideogram, was found written in ink on an object which is most likely related to the use of a building, also uncovered in the dig.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024