Home | Category: Minoans and Mycenaeans

MINOAN LIFE

Minoan golden bee

One gets a sense that the Minoans enjoyed life. They seemed to have a lot of leisure time, which they filled with sports, religion and the arts. Minoan artwork and sculpture often depicts bare breasted women, dancing figures, men playing sports, and people partying and shaking Egyptian rattles and singing so hard their ribs are pressed against their skin from lack of breath. Minoan art contrast markedly with early Mesopotamian and Egyptian art which was often rigid and formal.

The Minoans stored olive and grain in huge clay jars and drank wine. They harvested grain with sickles and knocked olives off of trees with sticks much as modern Cretens do today Childhood skull shaping has also been practiced by Minoans as well as by Egyptians, ancient Britons, Mayas and New Guinea tribes.

Human sacrifice although rare were sometimes performed. Skeletons and artifact from the archeological site of Anemospilia seem to show a human sacrifice that was interrupted in mid-course by an earthquake which not only finished off the sacrifice victim but also spelled doom for the sacrificers as well.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINOANS (3000-1400 B.C.): CRETE, HISTORY, ORIGIN, MYTHS, OTHER STATES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN SITES: CITIES, TOWNS, PALACES AND HILLTOP LABYRINTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN WRITING: LANGUAGES. HIEROGLYPHICS, LINEAR A europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN CULTURE: ART, FRESCOES AND THE COLOR PURPLE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THERA ERUPTION: TSUNAMI, END OF THE MINOANS AND AKROTIRI europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete” by Rodney Castleden (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Minoan World” by Arthur Cotterell (1979) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Religion” by Martin P. Nilsson (1925) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Religion” by Nanno Marinatos (1993) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of the Gods” by Jacquetta Hawkes (1968) Amazom.com

“The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and its Survival in Greek Religion” by Martin P. Nilsson (1927) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess: A Near Eastern Koine” by Nanno Marinatos (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Role of the Traditional Mediterranean Diet in the Development of Minoan Crete” (BAR International) by F. R. Riley (1999) Amazon.com;

“Minoans and Mycenaeans: Flavours of Their Time” by Yannis Tzedakis and Holley Martlew (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ariadne's Threads: The Construction and Significance of Clothes in the Aegean Bronze Age” (Aegaeum) (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Bronze Age Begins: The Ceramics Revolution of Early Minoan I and the New Forms of Wealth that Transformed Prehistoric Society” by Philip P. Betancourt (2009) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Crete: An Introduction” by Livingston Vance Watrous (2020) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Civilization” by Stylianos Alexiou (1960) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age Illustrated Edition

by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean” (Oxford Handbooks) by Eric H. Cline Amazon.com;

Life in Gournia — A Typical Minoan Town

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Of all the sites in the prehistoric Aegean, Gournia, on the eastern side of Crete, gives the best idea of what a Minoan town looked like, which Harriet Boyd understood after just three years of working there in the earlly 20th century. “The chief archaeological value of Gournia,” she wrote in her site publication, “is that it has given us a remarkably clear picture of the everyday circumstances, occupations, and ideals of the Aegean folk at the height of their true prosperity.” Buell agrees: “When most people think of Minoan archaeology they think in terms of the palaces as these monolithic elements devoid of settlements, but at Gournia we have the settlement and the palace, and that’s so important.” [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

“Between 2010 and 2014, Vance Watrous of the University of Buffalo and a yearly team of more than a hundred have added greatly to the picture of Gournia as a thriving urban center going back at least as far as the Protopalatial period (1900–1700 B.C.). In the course of both Boyd’s and Watrous’ excavations, more than 50 houses or areas with evidence of industrial activity have been uncovered — 20 areas producing pottery, 15 producing stone vases, 18 producing bronze and bronze implements, and some with evidence for textile production. At one location on the north edge of the settlement, Buell points out an area of burned bedrock inside a space identified as a foundry. “Here we have all sorts of scraps of bronze crucibles, bronze drips, copper scraps, and iron used for flux. Elsewhere, we also found a tin ingot, the closest known source of which is Afghanistan, and copper ingots from Cyprus, so it’s clear they are making and working metal into objects on the site,” he says.

Snake Goddess “One of the most important areas the team has excavated is on Gournia’s northern edge, where archaeologist John Younger of the University of Kansas has uncovered a complete pottery workshop where the town’s inhabitants were making both red clay coarse wares and buff clay fine wares. In one room of the workshop there is a heap of what Younger calls “gray matter,” which, when his team sectioned it and sent it for analysis, was identified as possibly being clay from Vasiliki Ware, similar to that used to make the distinctive Gournia pottery, called Mirabello Ware, that is found at sites all over eastern and central Crete. In another room, in a phase dating to the Neopalatial period, Younger found 15 intact pots sitting upright on some benches, and in another room he found four large jars with numerous smaller pots inside. “There were pots inside pots for storage, just like I have in my cupboard at home,” Younger says, “and each one was a unique shape, so I think this was a kind of shop.” In yet another room, he found 10 cups only slightly different from one another. “I think you came here, picked out the pots you wanted. You could say, ‘I want a set of these, or ten of those,’ and then they were made and left to dry out in the yard,” Younger explains. And in the summer of 2014, in a small area east of the workshop, the team found no less than 11 kilns superimposed on each other, further evidence of the impressive duration and scale of Gournia’s industrial production.

“Several structures originally explored by Boyd (but about which she never published) are the Minoan buildings she located on the north coast of Mirabello Bay, about 400 yards north of the site. In 2008 and 2009, Watrous returned to this area to clean and map it, at which time he was able to identify several of them and place them in the context of the entire site. “We found a large shed for storing ships, pithoi, anchors, and tackle for unloading cargo, as well as a cobbled street running from this harbor toward the town, all of which makes sense given the scale of the industrial production here,” Watrous says. By the Neopalatial period, nearly 4,000 years ago, Gournia had a fully functioning harbor with a monumental building linked to the palace and a wharf for seagoing ships that sent goods out from the town and brought them back from overseas as part of the eastern-Mediterranean-wide trade network in which the Minoans thrived.

Minoan Religion

While we can only guess at their religious beliefs, the remains of their artwork suggest a polytheistic framework featuring various goddesses, including a mother deity. The priesthood was also completely female, although the King may have had some religious functions as well. In fact the role of women- as religious leaders, entrepreneurs, traders, craftspeople and athletes far exceeded that of most other societies, including the Greeks. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

The Minoans had no temples and no large cult statues from what we can tell. Worship centered around sacred caves and groves where it is believed the Minoans believed to be their deities dwelled. Minoan religious objects consisted primarily of small terra-cotta statuettes. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Minoan palaces functioned as centers for rituals, although major religious activities also occurred at cult sites in the country such as caves, springs, and peak sanctuaries.

The Minoans worshiped what has been described as a mother goddess, or snake goddess. This goddess was associated with animals, particularly birds and snakes, the pillar and the tree, and sword and the double ax. She was often depicted with snakes around her arms and lions at her feet. Her companion Zeus, the Monoans believed, was born on Mt. Ida on Crete. A popular image of the mother goddess shows her as a bare breasted snake goddess with snakes crawling up her arms, circling her head and tied into a knot about her waist. One of the unusual things about the worship of snakes by the Minoans is that Crete has virtually no snakes.

Most of the sculpture of earth goddesses found before in 2000 B.C. in mainland Europe were plump big-breasted women with folds of fat and little lines representing their genitalia. On Asia Minor and the Cycladic islands off of Greece little girlish figures with small beasts triangles for genitalia were common between 2500-1100 B.C.

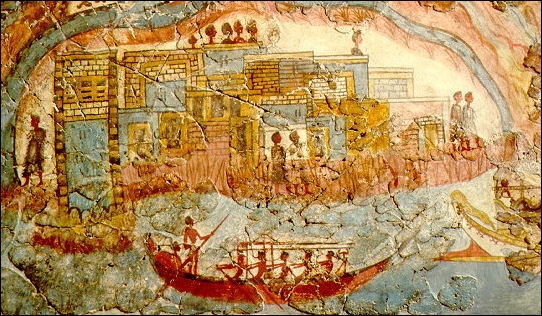

Akrotiri fresco of a Minoan town

The Minoans also worshiped male deities as reflected in the large number of male figures found and the quality of their craftsmanship. Egyptian symbols and deities, such as Orisis and Anubis, pop up frequently in Minoan religious iconography. Butterflies symbolized long life to the Minoans and bulls represented strength and fertility.

Minoan Religious Practices — Sacrifices and Sacred Prostitution?

The Minoans performed sacrifices: Archaeology reported: Often sacrificed dogs were single offerings, as was the case of the dog killed at the Minoan site of Monastiraki in Crete, where excavation director Athanasia Kanta in 2009 found a small bench with a skeleton of a dog (missing its head) and several conical cups arranged around it. Kanta interpreted the find as a sacrifice to appease the gods following a large earthquake — there are collapsed walls and fire damage throughout the site. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2010]

Some evidence of sacred prostitution has been found in Minoan Crete. A building known as the "East Building", also referred to as "the House of the Ladies" by archaeologists who excavated the building, contains architecture that some believed reflect the grooming needs of women, but could also have been a brothel for high status individuals. Large clay vats typically used for bathing were found within the building, along with successive doors within the corridors. The successive doors suggested privacy. Because the ground floors were found practically empty, the possibility that the building was used for prostitution increases. [Source Wikipedia]

There were also religious embellishments found within the "East Building", such as vases and other vessels that seemed to be connected to religious rituals. The vessels were covered in motifs related to sacrilegious rituals, such as the sacral knot and the image of birds flying freely. The functions of the vessels would have been offering food or liquid in relation to the rituals. Combining these two factors, it is a possibility that sacred prostitution existed within this building.

Minoans, Bulls and Bull Leaping

Bulls held a high place in Minoan culture. They appeared again and again in paintings and sculpture. Some have suggested that the Minoans worshiped bulls and that this may have grown from the cult surrounding the Egyptian god Hathor, who was often pictured as a divine cow.

Some scholars have said that the Minoans conducted sacrifices of bulls whose horns were covered with gold. Evans said that large double-headed axes found at Minoan sites were likely used to ritually kill bulls, arguing that they were too big to do anything else. Now it appears that the double headed ax was more likely a symbol of the equinox.

Some have suggested that bull leaping was a popular Minoan sport. Frescoes appear to depict male and female athletes doing flips over bulls charging at them at full speed. Some the “players” appear to grab the horns and hold on to the bull’s back as they leap over.

Scholars have interviewed rodeo experts to get their view on the depictions of of “bull leaping.” Some concluded that picture were not of bull leaping: the sport would simply be too dangerous, they say, as bulls usually turn their heads when confronted and anyone who tried to leap through their horns would likely be gored. Some scholars say that the “bull leaping” images represent something else, perhaps the constellations Taurus and Orion.

Minoan Society Palaces and Government

Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Around 1900 B.C., during the Middle Minoan period, Minoan civilization on Crete reached its apogee with the establishment of centers, called palaces, that concentrated political and economic power, as well as artistic activity, and may have served as centers for the redistribution of agricultural commodities. Major palaces were built at Knossos and Mallia in the northern part of Crete, at Phaistos in the south, and at Zakros in the east. These palaces are distinguished by their arrangement around a paved central court and sophisticated masonry. In general, there were no defensive walls, although a network of watchtowers punctuating key roads on the island has been identified. There were sanitary facilities as well as provisions for adequate lighting and ventilation. Living quarters of the palaces, like the better Minoan houses, were spacious. [Source: Colette and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002 metmuseum.org \^/]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “While it had been thought that the palaces supported a centralized political entity with the power to collect and redistribute taxes in the form of food, scholars are now much less sure than Evans was that this was how they actually functioned. Rather than being the locus of any sort of government with absolute control, an interpretation based on the model of the powerful urban temples of the ancient Near East, it seems more likely that they were autonomous entities used for communal rituals and ceremonies. It’s also possible that the palaces were storing large quantities of food for these events, as well as perhaps for the elite houses in the area, and paying rations to the artists and workers needed to build, decorate, and maintain each palace. Any or all of these uses would likely have led to the need to keep accurate records, which, in turn, led to the development of writing — the first in the ancient Aegean world — in the form of the script known as Linear A, as well as the use of Cretan hieroglyphics that were likely based on the Egyptian writing system. Archaeologists, beginning with Evans, have found many artifacts bearing these scripts, though both remain largely undeciphered. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

Minoan Society

The Minoans are believed to have lived in matriarchal society based on the prominent role that women played in their religion and mythology. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science, Their “Great Goddess held a spot above all other gods. Minoan art supports this idea, showing powerful priestesses who dominated religious ceremonies and women wielding battle axes and swords. Young Minoan women were trained in all the physical activities of their male peers and ran all aspects of their communities, while men spent months at a time at sea. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 12, 2015]

Successful and extensive trade resulted in a Minoan society that was wealthy and archaeology suggests that wealth was widely shared throughout the community. The extensive written records that do exist and have been deciphered show a highly controlled flow of goods into and out of state storehouses. The standard of living was high. Within the palace complexes… sophisticated plumbing, wonderful frescoes, plaster reliefs and open courtyards. Their system of government was that of a monarchy supported by a well-organized bureaucracy. [Source: Canadian Museum of History ]

Minoan Food

The Minoans raised cattle, sheep, pigs and goats, and grew wheat, barley, vetch and chickpeas. They also cultivated grapes, figs and olives, grew poppies for seed and perhaps opium. The Minoans also domesticated bees. Vegetables, including lettuce, celery, asparagus and carrots, grew wild on Crete. Farmers used wooden plows, bound with leather to wooden handles and pulled by pairs of donkeys or oxen.[Source Wikipedia]

Pear, quince, and olive trees were also native. Date palm trees and cats (for hunting) were imported from Egypt. The Minoans adopted pomegranates from the Near East, but not lemons and oranges. Linear B tablets indicate the importance of orchards (figs, olives and grapes) in processing crops for "secondary products". Olive oil was widely consumed. The process of fermenting wine from grapes was probably a factor of the "Palace" economies; wine would have been a trade commodity and an item of domestic consumption.

Seafood was also important in Cretan cuisine. The prevalence of edible molluscs in site material and artistic representations of marine fish and animals (including the distinctive Marine Style pottery, such as the "Octopus" stirrup jar) illustrate this importance. "Fishing was one of the major activities...but there is as yet no evidence for the way in which they organized their fishing." Cretans ate wild deer, wild boar and meat from livestock. Wild game is now extinct on Crete and scholars debate whether Minoans caused this.

Minoan Clothes and Hairstyles

Sheep wool was the main fibre used in textiles, and perhaps a significant export commodity. Linen from flax was probably much less common, and possibly imported from Egypt, or grown locally. There is no evidence of silk, but some use is possible. [Source Wikipedia]

Based on images in frescoes and sculptures, Minoans wore leopard skin loin clothes and colorful hippie-like outfits. Some statues show a women, or goddesses, wearing what looks like a 19th-century-style dress with an open area at the top for exposed breasts supported on a bodice. Minoan loin-clothes were similar to those worn by the Egyptians. Minoan men wore robes or kilts that were often long. Women wore long dresses with short sleeves and layered, flounced skirts. With both sexes, there was a great emphasis in art in a small waist, often taken to improbable extremes. Both sexes are often shown with rather thick belts or girdles at the waist. Women could also wear a strapless, fitted bodice, and clothing patterns had symmetrical, geometric designs.

Bernice Jones, a professor at Queens College in New York, reconstructed several Minoan garments, including the breast-revealing outfit of the snake goddess, a tube dress and a sheer top found in the depiction of a woman in a fresco in Thera’s House of Ladies, and a breast-revealing blouse worn by a dancer depicted in a fresco in Hagia Triada.

Men are shown as clean-shaven, and male hair was short, in styles that would be common today, except for some long thin tresses at the back, perhaps for young elite males. Female hair is typically shown with long tresses falling at the back, as in the fresco fragment known as La Parisienne, so named because when it was found in the early 20th century, a French art historian thought it resembled Parisian women of that time. Children are shown in art with shaved heads (often blue in art) except for a few very long locks; the rest of the hair is allowed to grow as they approach puberty. This can be seen in the Akrotiri Boxer Fresco.

World’s Oldest Flushing Toilet and Bathtub

The oldest known confirmed bath tub come from Minoa. Shaped somewhat like a modern tub, it was found in the palace of King Minos in Knossos and has been date to around 1700 B.C. Minoan nobility took baths in stone bathtubs "filled and emptied with vertical pipes cemented at their joints." Late these were replaced with glazed pottery pipes which were slotted together like modern ones and carried hot and cold water. The royal palace at Knossos also featured a latrine with an overhead water-holder that has been described as the world's first flush toilet.

The first flushing toilet, excavated at the palace of Knossos in Crete, washed waste from the toilet to the sewer. By the Hellenistic period large-scale public latrines brought toilets to the effluent masses. The world's oldest toilet is generally thought to be a seat-like structure excavated in Iraq's Tell Asmar. According to Cambridge archeologist Augusta McMahon, the first simple toilets were Mesopotamian pits, about 1 meter in diameter, over which users would squat. The pits were lined with hollow ceramic cylinders that prevented excrement from escaping. Approximately 1000 years later the Minoans invented the flush.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 20, 2016]

Minoan-Era Beer Found on Mainland Greece

In 2018, Archaeologists from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki announced they had located several archaeobotanical remains of a cereal that could have been used in beer brewing. Similar remains found in the Archontiko area in the island of Corfu were also discovered in Argissa in Zakynthos. Tornos News reported: At Archontiko, archaeologists found about 100 individual cereal seeds dating back to the early Bronze Age from 2100 to 2000 B.C.. In Argissa, they found about 3,500 cereal seeds going back to the Bronze Age, approximately from 2100 to 1700 B.C.. [Source Tornos News, June 26, 2018]

Minoan bathtubs at The Heraklion Archaeological Museum from Toilet Guru toilet-guru.com

Moreover, archaeologists discovered a two-room structure that seems to have been carefully constructed to maintain low temperatures in the Archontiko area, suggesting it was used to process the cereals for beer under the right conditions. This discovery is the earliest known evidence of beer consumption in Greece, but not in the planet. Beer is one of the oldest beverages humans have produced, dating back to at least the 5th millennium B.C. in Iran, and was recorded in the written history of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia and spread throughout the world.

In the case of Archontiko, along with rich cereal residues, a concentration of germinated cereal grains, ground cereal masses and fragments of milled cereals were found inside the remains of two houses. Their condition is put down to malting and charring, claim researchers. The practice of brewing could have reached the Aegean region and northern Greece through contacts with the eastern Mediterranean where it was widespread, it is also suggested.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024