Home | Category: Bronze Age Europe / Minoans and Mycenaeans

MINOANS

The Minoans were arguably Europe's first great civilization. They originated on the island of Crete around 3000 B.C. and flourished there from 2000 B.C. to 1,450 B.C. While most of Europe was still in the Stone Age the Minoans created cities with magnificent palaces and comfortable townhouses with terra cotta plumbing; traded throughout the Mediterranean and the Aegean with a huge fleet of ships; and developed a writing system. The Minoans are named by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the legendary King Minos, son of Zeus and Europa, who is said to have lived on Crete. According to myth, a King Minos, living in a palace with more than a thousand rooms, once ruled the island of Crete. In 1900 such a palace was discovered, excavated and partially restored Evans. [Source: Joseph Judge, National Geographic, February 1978]

The Minoans were arguably Europe's first great civilization. They originated on the island of Crete around 3000 B.C. and flourished there from 2000 B.C. to 1,450 B.C. While most of Europe was still in the Stone Age the Minoans created cities with magnificent palaces and comfortable townhouses with terra cotta plumbing; traded throughout the Mediterranean and the Aegean with a huge fleet of ships; and developed a writing system. The Minoans are named by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the legendary King Minos, son of Zeus and Europa, who is said to have lived on Crete. According to myth, a King Minos, living in a palace with more than a thousand rooms, once ruled the island of Crete. In 1900 such a palace was discovered, excavated and partially restored Evans. [Source: Joseph Judge, National Geographic, February 1978]

It is virtually impossible to talk about early Greek history without at some point introducing the Minoans. They preceded classical Greece by 2000 years and where to believed to have been sent into a downward spiral by the a volcanic eruption four times more powerful than Krakatoa. The Minoans were not Greeks nor do they appear to be closely related. What seems clear however is that they helped to shape the early Greek civilization...The Minoans have left a stunning visual legacy (paintings, sophisticated palaces and varied artwork) as well as large quantities of written records.” [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Minoa was a Bronze Age culture and a contemporary of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia and Babylon. The Minoan golden age was between 1600 and 1450 B.C., when large palaces were built in Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia and Zakros and Minoa had colonies on the islands of Kythera and Rhodes and trading posts as far away as Syria. At that time Egypt was at its height under Ramses III and the Trojan War and the Israelite's Exodus to the Promised Land was still 300 years in the future.

Jessica Cecil wrote for the BBC: “The lost world of the Minoans has intrigued people for thousands of years. Their palace at Knossos was vast and elaborate, with Europe's first paved roads and running water. The ancient Greeks wove its magnificence into their myths; it was the home of King Minos and his man-eating bull, the Minotaur, which roamed the palace labyrinth. In the 1900s, British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans excavated and restored the ruins at Knossos. Beautiful and delicate frescoes of bulls and dolphins revealed a highly artistic civilisation and a people who apparently lived in harmony with nature.” [Source: Jessica Cecil, BBC, February 17, 2011]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINOAN SITES: CITIES, TOWNS, PALACES AND HILLTOP LABYRINTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN WRITING: LANGUAGES. HIEROGLYPHICS, LINEAR A europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN LIFE: SOCIETY, RELIGION, FOOD, BATHTUBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MINOAN CULTURE: ART, FRESCOES AND THE COLOR PURPLE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THERA ERUPTION: TSUNAMI, END OF THE MINOANS AND AKROTIRI europe.factsanddetails.com

Good Archaeology Websites Aegean Prehistoric Archaeology sites.dartmouth.edu; Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/ ; Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Minoan Crete: An Introduction” by Livingston Vance Watrous (2020) Amazon.com;

“Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete” by Rodney Castleden (1990) Amazon.com;

“Minoan Civilization” by Stylianos Alexiou (1960) Amazon.com;

“The Minoans” by Ellen Adams (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Minoans: Crete in the Bronze Age” by Sinclair Hood (2002), lots of illustrations, Amazon.com;

“The Destruction of Knossos: The Rise and Fall of Minoan Crete” by H. E. L. Mellersh (1970) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age Illustrated Edition

by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine Amazon.com;

"The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean” (Oxford Handbooks) by Eric H. Cline Amazon.com;

“The Aegean Bronze Age” by Oliver Dickinson (Cambridge World Archaeology) (1994) Amazon.com;

“Greece in the Bronze Age” by Emily Vermeule (1964) Amazon.com;

“The Goddess and the Bull: A Study in Minoan-Mycenaean Mythology ” by Helen Benigni (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Bull of Minos” by Leonard Cottrell (1955) Amazon.com;

“Mysteries of the Snake Goddess” by Kenneth Lapatin (2002) Amazon.com;

“Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth” by J. A. MacGillivray (2000) Amazon.com;

"The Minoan Shipwreck at Pseira, Crete" by Dr. Elpida Hadjidaki-Marder PhD (2021) Amazon.com;

Crete

Minoan ceramics Crete (12 hours from Piraeus, 6 hours from Santorini by ferry) is the largest and southernmost island in Greece and the fifth largest in the Mediterranean. Home of the Minoans from 2600 B.C. to 1450 B.C., it extends 270 kilometers (160 miles) from east to west. At the center it is 60 kilometers (37 miles) north to south, while on the east, near the town of Ierapetra, not far from Gournia, the island stretches just seven and a half miles from coast to coast.

According to Archaeology magazine: The landscape varies from snow-topped mountains, the highest of which, Mount Ida, reaches more than 8,000 feet, to deep gorges and caves, expansive valleys, fertile plateaus, and sandy beaches, all surrounded by the blue waters of the Aegean Sea. Located at the crossroads of three continents, Crete has attracted visitors, travelers, and traders for thousands, and even tens of thousands, of years. The island has had an important role in the Mediterranean at many times, both ancient and modern, and has been a prized possession of major powers from the third millennium B.C. through the cultures of the Mycenaeans, Romans, Byzantines, Venetians, and Ottomans, and as an occupied territory of Hitler’s Third Reich. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

Ruins of Minoan Culture are found on Crete Knossos, Phaestos, Malia and Kato Zakros. In the south there are lovely beaches, in the interior are massive rocky mountains that are sometimes covered in snow and in the west there is the famous Samarian Gorge. Crete was at one time covered with oaks, chestnuts, pine trees and cypresses. The hills of the island are now largely denuded.

“Thousands of years before Evans discovered the first evidence of the Minoans, Crete had long been known as the subject of myth and legend. Fearing the wrath of her husband Kronos, who had devoured his other children, the goddess Rhea secretly gave birth to her son Zeus, the most powerful of the Greek gods, in the Dikteon Cave in the mountains of central Crete. It was back to Crete, too, that Zeus, in the form of a white bull, took the Phoenician woman Europa, where she became queen of the island and mother to King Minos. And for the Athenians of the Golden Age, their great hero and king, Theseus, also had a Cretan past, for it was on the island that he slew the Minotaur and escaped the prison of King Minos’ labyrinth.

“Yet it was not only in their myths that the ancient Greeks spoke of Crete. In the Odyssey, which is thought to reflect events of the Late Bronze Age, Homer describes Crete as a “lovely land, washed by waves on every side, densely populated and boasting 90 cities....Among their cities is the great city of Knossos, where Minos reigned.” The Greek poet Hesiod told of “Cretans from Knossos, the city of Minos…who sailed their black ship to sandy Pylos [a Bronze Age settlement on the Greek mainland],” and the fifth-century B.C. historian Thucydides wrote that Crete was the first place “to rule over the sea.” Although these writers were more than 1,500 years removed from the Minoans, nearly as far away in time as we are from the last days of the Roman Empire, Crete’s ancient inhabitants were revered and remembered as representatives of a sophisticated culture that, with its distinctive art, language, system of government, and maritime abilities, became Europe’s first great civilization.

Minoan Civilization

The concept of Minoan civilisation was first developed by Sir Arthur Evans, a British archaeologist who unearthed the Bronze Age palace of Knossos on Crete. He named the people who built Knossos and other cities after the legendary King Minos who, according to tradition, ordered the construction of a labyrinth on Crete to hold the mythical half-man, half-bull creature known as the minotaur. Evans believed that the real-life Bronze Age culture on Crete must have originated from somewhere else, suggesting the Minoans were perhaps refugees from Egypt's Nile delta who fled the region after it was conquered by a southern king some 5,000 years ago. Evidence to back up the theory included some similarities between Egyptian and Minoan art and resemblances between circular tombs built by the early inhabitants of southern Crete and those built by ancient Libyans. [Source: BBC, 15 May 2013]

Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Sir Arthur Evans, the British archaeologist, characterized the Bronze Age culture of Crete as Minoan, after the legendary King Minos. From the material he excavated at Knossos, Evans devised a chronological scheme consisting of nine periods for Minoan civilization on Crete. His Early, Middle, and Late Minoan periods, each with three subdivisions, roughly followed the tripartite division of Egyptian history in the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms. Our knowledge of Early Minoan Crete comes primarily from burials and a number of excavated settlement sites. Artistic works of this period indicate that advances were made in gem engraving, stoneworking (especially vases), metalworking, and pottery. Terracotta bowls on high pedestals appeared and burnishing tools were used for decoration. [Source: Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002 metmuseum.org \^/]

The Minoans were the first great maritime culture. They used sailing ships with oars and are believed to have invented the keel. They stored foodstuffs in massive jars called pithons . The Minoans traded all over the Mediterranean. To make bronze the Minoans traded with Cyprus for copper and with Assyrian traders for tin from Anatolia and the Hindu Kush mountains. The Minoans grew rich from trade with Egypt and the East Mediterranean. Based on the fact that Minoan ports had elaborate harbors and Minoan goods have been found in Egypt and elsewhere it was believed they were primarily traders. No Minoan shipwreck has ever been found. Archaeologists would love to get their hands on one.

A lack of depictions of war and the fact that few fortifications have been found around Minoan cities and has led archaeologists to believe that warfare was uncommon in Minoa and the Minoans were a peaceful people that devoted their attentions to the arts not the military. They made some of the world's first frescoes, jewelry with precious stones, and thin-shelled pottery. The also left behind a written language that was undeciphered until the 1990s.

Origins of the Minoans

Based on the evidence currently available, it seems that the Minoans arrived on the large island of Crete more than 5000 years ago. The soil was fertile, the climate was favorable and the numbers of people increased. Eventually a point was reached when the resources of the land were insufficient to meet the needs of the expanding population. Many migrated to nearby islands, those that stayed turned increasingly to trade as a means of improving their economic situation. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Evans suggested that the Minoans were refugees forced from northern Egypt by invaders more than 5,000 years ago. In the era in which he was working, it seemed impossible to imagine a sophisticated Bronze Age Aegean civilization that didn’t have some ties to Egypt, whose considerable antiquity, religious and political complexity, and architectural and artistic achievements had been well known for some time. In fact, Evans based his chronology of Minoan civilization on the Egyptian model of Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, dividing its history into periods he called Early, Middle, and Late, and further subdividing it using Roman numerals and letters where more precise dates were required. [Source:Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

“For many decades, however, most scholars have doubted Evans’ concept of Minoan origins. As to the question of when the original settlers came, likely over the course of several migratory events, “we should probably focus on the Neolithic as the first period of sustained settlement and expansion on the island,” says archaeologist and Aegean prehistorian John Cherry of Brown University. “For earlier periods, before the seventh millennium B.C., evidence of settlement tends to wink on and off, perhaps indications of seasonal occupation only, or even of local extinctions.” Some have suggested that the ancestors of the Greeks and Minoans were the Luvians, an 8000-year-old people from the hills of Anatolia.

Evidence of People on Crete 130,000 Years Ago

Hand axes found on Crete suggest hominids made sea crossings to go 'out of Africa' Bruce Bower wrote in Science News: “ Human ancestors that left Africa hundreds of thousands of years ago to see the rest of the world were no landlubbers. Stone hand axes unearthed on the Mediterranean island of Crete indicate that an ancient Homo species — perhaps Homo erectus — had used rafts or other seagoing vessels to cross from northern Africa to Europe via at least some of the larger islands in between, says archaeologist Thomas Strasser of Providence College in Rhode Island. [Source: Bruce Bower, Science News, January 11, 2010 +]

Dolphin room at Knossos

“Several hundred double-edged cutting implements discovered at nine sites in southwestern Crete date to at least 130,000 years ago and probably much earlier, Strasser reported January 7 at the annual meeting of the American Institute of Archaeology. Many of these finds closely resemble hand axes fashioned in Africa about 800,000 years ago by H. erectus, he says. It was around that time that H. erectus spread from Africa to parts of Asia and Europe. +\

“Until now, the oldest known human settlements on Crete dated to around 9,000 years ago. Traditional theories hold that early farming groups in southern Europe and the Middle East first navigated vessels to Crete and other Mediterranean islands at that time. "We're just going to have to accept that, as soon as hominids left Africa, they were long-distance seafarers and rapidly spread all over the place," Strasser says. Other researchers have controversially suggested that H. erectus navigated rafts across short stretches of sea in Indonesia around 800,000 years ago and that Neandertals crossed the Strait of Gibraltar perhaps 60,000 years ago. +\

“Questions remain about whether African hominids used Crete as a stepping stone to reach Europe or, in a Stone Age Gilligan's Island scenario, accidentally ended up on Crete from time to time when close-to-shore rafts were blown out to sea, remarks archaeologist Robert Tykot of the University of South Florida in Tampa. Only in the past decade have researchers established that people reached Crete before 6,000 years ago, Tykot says. Strasser's team cannot yet say precisely when or for what reason hominids traveled to Crete. Large sets of hand axes found on the island suggest a fairly substantial population size, downplaying the possibility of a Gilligan Island's scenario, in Strasser's view. +\

In excavations conducted near Crete's southwestern coast during 2008 and 2009, Strasser's team unearthed hand axes at caves and rock shelters. Most of these sites were situated in an area called Preveli Gorge, where a river has gouged through many layers of rocky sediment. At Preveli Gorge, Stone Age artifacts were excavated from four terraces along a rocky outcrop that overlooks the Mediterranean Sea. Tectonic activity has pushed older sediment above younger sediment on Crete, so 130,000-year-old artifacts emerged from the uppermost terrace. Other terraces received age estimates of 110,000 years, 80,000 years and 45,000 years. These minimum age estimates relied on comparisons of artifact-bearing sediment to sediment from sea cores with known ages. Geologists are now assessing whether absolute dating techniques can be applied to Crete's Stone Age sites, Strasser says. +\

“Intriguingly, he notes, hand axes found on Crete were made from local quartz but display a style typical of ancient African artifacts. "Hominids adapted to whatever material was available on the island for tool making," Strasser proposes. "There could be tools made from different types of stone in other parts of Crete."” +\

DNA Evidence Indicates the Minoans Came from Europe

In May 2013, scientists said that analysis of DNA from ancient remains on Crete suggested the Minoans were indigenous Europeans and didn’t come from Egypt, Africa, Anatolia or the Middle East as some scholars had suggested. The research appeared in Nature Communications journal and was co-authored by George Stamatoyannopoulos of the University of Washington in Seattle, [Source: BBC, 15 May 2013 ++]

The BBC reported: “In this study, Prof Stamatoyannopoulos and colleagues analysed the DNA of 37 individuals buried in a cave on the Lassithi plateau in the island's east. The majority of the burials are thought to date to the middle of the Minoan period - around 3,700 years ago. The analysis focused on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) extracted from the teeth of the skeletons, This type of DNA is stored in the cell's "batteries" and is passed down, more or less unchanged, from mother to child. They then compared the frequencies of distinct mtDNA lineages, known as "haplogroups", in this ancient Minoan set with similar data for 135 other populations, including ancient samples from Europe and Anatolia as well as modern peoples. ++

Minoan Palace at Knossos

“The comparison seemed to rule out an origin for the Minoans in North Africa: the ancient Cretans showed little genetic similarity to Libyans, Egyptians or the Sudanese. They were also genetically distant from populations in the Arabian Peninsula, including Saudis, and Yemenis. The ancient Minoan DNA was most similar to populations from western and northern Europe. The population showed particular genetic affinities with Bronze Age populations from Sardinia and Iberia and Neolithic samples from Scandinavia and France. They also resembled people who live on the Lassithi Plateau today, a population that has previously attracted attention from geneticists. ++

“The authors therefore conclude that the Minoan civilisation was a local development, originated by inhabitants who probably reached the island around 9,000 years ago, in Neolithic times. "There has been all this controversy over the years. We have shown how the analysis of DNA can help archaeologists and historians put things straight," Prof Stamatoyannopoulos told BBC News. "The Minoans are Europeans and are also related to present-day Cretans - on the maternal side. It's obvious that there was very important local development. But it is clear that, for example, in the art, there were influences from other peoples. So we need to see the Mediterranean as a pool, not as a group of isolated nations.There is evidence of cultural influence from Egypt to the Minoans and going the other way." ++

Minoans and Greece

Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: Although Crete is separated from the Greek mainland by only about 160 kilometers (100 miles), the people who lived on the island in the early second millennium B.C. did not have much in common with their neighbors across the Aegean Sea. By 1900 B.C., a sophisticated culture existed on Crete, boasting palaces built using finely cut stonework known as ashlar, a belief system that featured a central goddess figure and other divinities, and the widespread use of bull imagery in its art, none of which were in evidence at this time on the mainland. [Source:Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

Excavations at Minoan sites on the island undertaken over the last century show that, starting in the late third millennium B.C., the Minoans’ trade networks were far more extensive than those of contemporary mainlanders. Artifacts found at such Cretan sites as Knossos include imported stone vases and jewelry from Egypt and the Levant, rare commodities on the mainland at this time. The Minoans further distinguished themselves from the mainlanders by their artistic prowess, particularly with regard to gold- and stonework. Minoan craftsmanship was, for centuries, superior to anything found on the mainland.

Greece gave rise to the Mycenaeans. “For a time, the Mycenaeans both imported Minoan luxury goods and incorporated Minoan symbols, including the bull, into their own art. The richest Mycenaeans were buried with Minoan luxury goods, while some other graves included locally produced Mycenaean objects, such as painted pottery, that were often excellent-quality copies of Minoan originals. The Mycenaeans also borrowed the Minoan script, called Linear A, and adapted it to their own use; this script is now called Linear B. Mycenaean society, too, began to change shape. What began as a loose collection of small villages became more and more hierarchical, with power concentrated in the hands of the palace-dwelling members of society featured in the works of Homer.

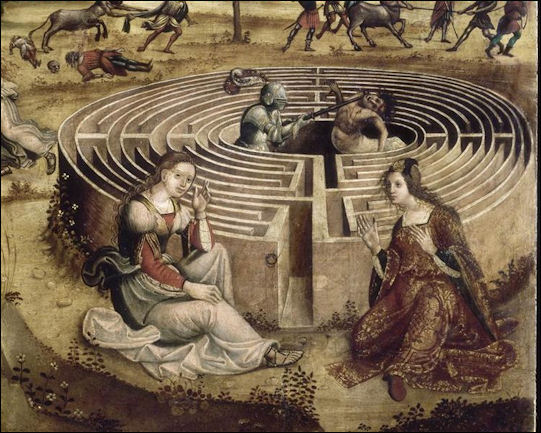

medieval rendering of the Minotaur myth

Minotaur, Theseus and the Labyrinth

Knossos (6 kilometers south of Iraklion) was the capital of the Minoan empire, Europe's first great civilization. It is also where you'll find a palace reportedly used by King Minos. There is no evidence however of the legendary Minotaur or the Labyrinth, despite the fact the ruins sometimes resemble a maze.

The story of the Minotaur and the labyrinth, according to to some, is set in Crete, presumably during the Minoan era. According to legend, King Minos was a wise leader and a just lawgiver who ruled Crete from Knossos and lived in a magnificent palace. One day the sea-god Poseidon gave him a magnificent white bull that was intended to be sacrificed in the sea god's honor. Minos greedily kept the bull instead and Poseidon got even with the king by casting a spell on his wife, which made her want to make love with the bull, which she did, producing the Minotaur. Daedalus, the Athenian architect who later tried to fly to Sicily with wings made of wax, built the Labyrinth to imprison the Minotaur.

After King Minos's son was killed in Athens the king captured Athens and secured an annual tribute of seven youths and seven virgins to be eaten by the Minotaur. One of youths offered to the Minotaur — Theseus — fell in love with King Minos's daughter. Daedalus gave Theses a ball of string so that he could find his way out of the labyrinth of he managed to kill the Minotaur. After slaying the Minotaur Theseus fled Crete with king’s daughter but as was true with heros in other Greek myths, such as Jason from the Argonauts, Theseus abandoned the girl after winning his freedom.

The Minoans believed that King Minos was the son of Europa, the daughter of King Sidon, and Zeus transformed into a bull. The association of the Minotaur myth with Knossos can be traced to Sir Arthur Evans, the British adventurer, who excavated Knossos in the 1890s. He reportedly was struck by the size of Knossos and its large number of rooms that he figured it must be the source of the labyrinth myth. Some have said he defied one of the cornerstones of archaeology by forcing evidence to fit his model rather than letting evidence speak for itself. Evans is also the source of some other dubious claims about Minoa.

Herodotus and Plutarch on Minos and Knossos

Jerome Arkenberg at Northern Illinois University wrote: Here are two texts on the Minoans. Of course, these have always been suspect. However, recent archaeological finds have begun to show the kernel of truth in both the tale of Theseos — and the child sacrifice that occurred in the Labyrinth — and Herodotus' accounts of the two depopulations of Crete do seem to have a basis in fact. Of course, Herodotus doesn't mention the Thera explosion, but famine and pestilence which would undoubtedly have accompanied that blast appears to have remained in Greek memory. [Source: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Hellenistic World, Fordham University]

Herodotos wrote in The History, VII.170-171: “Minos, according to tradition, went to Sicania, or Sicily, as it is now called, in search of Daidolos, and there perished by a violent death....Men of various nations now flocked to Crete, which was stripped of its inhabitants; but none came in such numbers as the Hellenes. Three generations after the death of Minos the Trojan war took place; and the Cretans were not the least distinguished among the helpers of Menelaos. But on this account, when they came back from Troy, famine and pestilence fell upon them, and destroyed both the men and the cattle. Crete was a second time stripped of its inhabitants, a remnant only being left; who form, together with fresh settlers, the third Cretan people by whom the island has been inhabited. [Source: Herodotus, “The History,” George Rawlinson, trans., (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

In “The Life of Theseus”, “Plutarch wrote: “Not long after arrived the third time from Crete the collectors of the tribute which the Athenians paid them upon the following occasion. Androgeos having been treacherously murdered in the confines of Attica, not only Minos, his father, put the Athenians to extreme distress by a perpetual war, but the gods also laid waste their country; both famine and pestilence lay heavy upon them, and even their rivers were dried up. Being told by the oracle that, if they appeased and reconciled Minos, the anger of the gods would cease and they should enjoy rest from the miseries they labored under, they sent heralds, and with much supplication were at last reconciled, entering into an agreement to send to Crete every nine years a tribute of seven young men and as many virgins, as most writers agree in stating; and the most poetical story adds, that the Minotaur destroyed them, or that, wandering in the labyrinth, and finding no possible means of getting out, they miserably ended their lives there. [Source: Plutarch, Plutarch's Lives, John Dryden, trans., (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910]

“Theseos, who, thinking it but right to partake of the sufferings of his fellow-citizens, offered himself for one without any lot....When he arrived at Crete, as most of the ancient historians as well as poets tell us, having a clue of thread given him by Ariadne, who had fallen in love with him, and being instructed by her how to use it so as to conduct him through the windings of the labyrinth, he escaped out of it and slew the Minotaur, and sailed back, taking along with him the Athenian captives....

“Years later, after Minos' decease, Deucalion, his son, desiring a quarrel with the Athenians, sent to them, demanding that they should deliver up Daidalos to him, threatening upon their refusal, to put to death all the young Athenians whom his father had received as hostages from the city. To this angry message Theseos returned a very gentle answer excusing himself that he could not deliver up Daidalos, who was his cousin, his mother being Merope, the daughter of Erechtheos. In the meanwhile Theseos secretly prepared a navy. As soon as ever his fleet was in readiness, he set sail, having with him Daidalos and other exiles from Crete for his guides; and none of the Cretans having any knowledge of his coming, but imagining when they saw his fleet that they were friends and vessels of their own, he soon made himself master of the port, and immediately making a descent, reached Knossos before any notice of his coming, and, in a battle before the gates, put Deucalion and all his guards to the sword.

Theseus and Minotaur mosaic

Periods of Minoan History

Minoan civilization began evolving around 3000 B.C. around the start of the Bronze Age. At that time the early Minoans used bronze and copper along with bone and stone weapons. The first examples of artistic decorations on pottery and walls appeared around 2850 B.C. By 2500 B.C. they were producing decorative jewelry and stone vases. Archaeologists now mark the period between 3000 B.C. and 2000 B.C. as the Early Period of Minoan civilization. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

The Middle Period of Minoan civilization lasted from around 2000 B.C. to 1700 B.C. Early flush toilets were developed around 2000 B.C. and early Minoan writing first appeared between 2000 to 1850 B.C. The Late Period lasted from around 1700 B.C. to 1450 B.C. Fires destroyed many palaces in 1450 B.C. The last palaces in Knossos was abandoned by 1300 B.C. . The destructive Thera eruption occurred in 1645 B.C. The period between 1450 and 1000 B.C. has been labeled the Sub-Minoan, a long period of decline that culminated with the end of Minoan culture in 1050 B.C.

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “For the oldest era of Minoan civilization, Evans’ Early Minoan period, the evidence comes from burials and small settlements dating to between 3100 and 1900 B.C. These finds demonstrate that, early on, the Minoans were excellent sailors who were actively trading with Egypt and the Near East, exchanging their cloth, timber, foodstuffs, and, likely, olive oil, for copper, tin, gold, silver, and ivory. It’s also clear that the Minoans were developing great skill as potters, metalsmiths, engravers, and creators of the carved stone vases that would become distinctive and valuable exports for more than a millennium to come. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

“At the start of the second millennium B.C., a major change occurred in Minoan civilization. During the Protopalatial and Neopalatial periods, which correspond to Evans’ Middle Minoan IB through Late Minoan I periods, the Minoans built “palaces” (Evans’ name for these centers has persisted and is the basis for another system of chronology in which Minoan history is divided into Pre-, Proto-, Neo-, and Postpalatial eras) at locations mostly in the eastern part of the island including Knossos, Malia, Phaistos, and Zakros. These palaces were large stone multistoried building complexes arranged around open, paved courtyards, and contained spaces for industrial activities, food processing and storage, religious celebrations, domestic use, sporting contests, and administrative functions — more of a city core than the single domestic entity that “palace” connotes. The palaces were equipped with elaborate staircases and sophisticated drainage and plumbing, and were also decorated with brightly colored frescoes, some of the most accomplished examples of painting in ancient Greece, depicting primarily scenes from nature and daily life.

“In about 1700 B.C., the Minoan palaces were destroyed, probably by a massive earthquake, but were soon rebuilt and redecorated, ushering in two and a half centuries that saw the height of Minoan civilization. With well-established trade networks exchanging raw materials and luxury objects, and a relatively stable political environment, the Minoans flourished, although not as the preternaturally peaceful society pictured by Evans and his contemporaries. Most larger Minoan towns were, in fact, fortified. A second widespread destruction of the palaces in about 1450 B.C., possibly at the hands of Mycenaeans from mainland Greece, resulted in a blending of Minoan and Mycenaean cultures that eventually led to the decline of the Minoan civilization.

Reconstructed Minoan fresco found in Avaris, Egypt

Minoan-Egyptian Relations

The Minoan civilization (c. 3000 – 1400 B.C.) of Crete existed at the same time as the Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom of Egypt. Stefan Pfeiffer of Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg wrote: “Occupying the island of Crete, the Minoans were skilled sailors who had established hegemony in the Aegean; it was therefore natural that they made contact with neighboring civilizations. With Egypt they established mainly economic relations as far as can be judged by archaeological evidence. First contacts between Crete and Egypt are attested by a fragment of a 1st or 2nd Dynasty Egyptian obsidian vase found in Crete in an EM-II-A stratum, testifying to (indirect?) trading contacts since earliest historical times. [Source: Stefan Pfeiffer, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“There were three possible routes by which the Minoans (or their trade goods) could have traveled to Egypt. First, there was the direct passage over 350 miles of open sea, which does not seem very likely. The second option was to sail within sight of the shore along the Levantine coast (and probably trade with the settlements there) to (later) Pelusium. The third, and most likely, passage was to cross the Mediterranean to (later) Cyrene and then sail along the coast to Egypt. The Minoans valued gold, alabaster, ivory, semiprecious stones, and ostrich eggs, but Egyptian stone vessels and scarabs were also found in Crete. Some scholars maintain that Egyptian craftsmen were present on the island, based upon a statuette (14 centimeters high) of an Egyptian goldsmith called User that was found at Knossos; this single example, however, should not be considered as evidence for the migration of Egyptian craftsmen. In addition to these items of Egyptian origin, a certain adaptation of Egyptian styles in Minoan art is apparent. The Minoan artisans used some Egyptian elements eclectically, adjusting or adapting their meaning to new contexts.

“Conversely, Egypt imported Minoan pottery, metal vessels, and jewelry, and probably also wine, olive oil, cosmetics, and timber, as the archaeological record proves. We know that the first Minoan artifacts found in Egypt do not date prior to the time of Amenemhat II (1928 – 1893 B.C.), because from his times Middle-Minoan pottery (so-called Kamares ware) is attested. All in all, Minoan culture had at least some influence in Egypt, as can be judged from Egyptian copies of Kamares ware. Even Minoan textiles seem to have been appreciated by the Egyptian elite, as Aegean textile patterns were copied on the walls of tombs from the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.

“The pinnacle of Minoan-Egyptian relations can be dated to the beginning of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. Having already established good relations with the Hyksos, the Minoans stayed in close contact with a number of Egyptian pharaohs as well, as is proven by Minoan frescoes found in two palaces at Tell el- Dabaa/Avaris in the Nile delta. It was at first assumed that these royal houses were decorated during the rule of the Hyksos kings, but this view has been revised. It is now clear from the stratigraphical evidence that the palaces date to the Thutmosid era. Contemporary with this evidence from Lower Egypt are scenes in seven Theban tombs of 18th- Dynasty high court officials that show Minoan legates from “Keftiu “(as Crete is called in Egyptian texts) bearing tribute. According to some scholars, these scenes bear witness to reciprocity of political contacts rather than formal tribute to a dominant partner. Thus the Minoan frescoes in the Lower Egypt and the pictorial evidence in tombs of almost the same period in Upper Egypt underscore rich cultural, economic, and eventually even political, contacts between Egypt and the Minoan civilization during the 18th Dynasty, just before the time of Akhenaten. This is corroborated by the fact that some Egyptian scribes seem to have known the Minoan language .”

Links Between Myceneans and Minoans

Nicholas Wade wrote in the New York Times: “The palaces found at Mycene, Pylos and elsewhere on the Greek mainland have a common inspiration: All borrowed heavily from the Minoan civilization that arose on the large island of Crete, southeast of Pylos. The Minoans were culturally dominant to the Mycenaeans but were later overrun by them...The Mycenaeans used the Minoan sacred symbol of bull’s horns on their buildings and frescoes, and their religious practices seem to have been a mix of Minoan concepts with those of mainland Greece.... The transfer was not entirely peaceful: At some point, the Mycenaeans invaded Crete, and in 1450 B.C., the palace of Knossos was burned, perhaps by Mycenaeans.[Source: Nicholas Wade, New York Times, October 26, 2015 ^^]

“If the earliest European civilization is that of Crete, the first on the European mainland is the Mycenaean culture...It is not entirely clear why civilization began on Crete, but the island’s population size and favorable position for sea trade between Egypt and Greece may have been factors. “Crete is ideally situated between mainland Greece and the east, and it had enough of a population to resist raids,” said Malcolm H. Wiener, an investment manager and expert on Aegean prehistory. ^^

“The Minoan culture on Crete exerted a strong influence on the people of southern Greece. Copying and adapting Minoan technologies, they developed the palace cultures such as those of Pylos and Mycene. But as the Mycenaeans grew in strength and confidence, they were eventually able to invade the land of their tutors. Notably, they then adapted Linear A, the script in which the Cretans wrote their own language, into Linear B, a script for writing Greek.” ^^

Minoan auroch

Discovery of Minoa and Archaeology There

The Palace of Knossos and Minoan culture were discovered in 1900 by Sir Arthur Evans, an Englishman who had come to Crete to search for information about the origins of Mycenaean culture. Evans traveled to Crete several ties between 1894 and 1899. He began his search at the mound of Kephala, outside Heraklion, where seals with Mycenaean-like marking were found. Twenty-five years he finished excavating the 5½ acre Knossos Palace.

Evans used his own personal fortune, worth several million dollars in today's money, to finance the dig. Based on the presence of numerous images of bulls and the maze -like quality of the palace, he decided that Knossos was the source of the Minotaur myth and labyrinth story. He also found written scripts which he labeled Linear A and Linear B. Evans work as an archeologist was shoddy to say the least. He replaced missing columns and support beams with reinforced concrete. Archaeologists that followed found concrete covering up the original gypsum and sandstone. In the original excavations and Evan did not indicate different time periods.

Other important Minoan sites include the Gorge of the Dead, an unplundered palace found in 1962 by Nicoloaos Platon in Zakros; a Bronze Age settlement on Santorini preserved like Pompeii found on Spyridon Marinatos; burial chambers of a queen or priestess found in Arkhanes; the grand stair case of Phaistos, the central court at Mallia, and the throne room of Knossos.

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Thanks to Evans’ work at Knossos, as well that of the French at Malia, Italians at Phaistos, and Greeks at Zakros, a great deal was known from an early stage of research about the large palace sites of the Proto- and Neopalatial periods of Minoan history. Of all the sites in the prehistoric Aegean, Gournia gives the best idea of what a Minoan town looked like, which Harriet Boyd understood after just three years of working there in the earlly 20th century. “The chief archaeological value of Gournia,” she wrote in her site publication, “is that it has given us a remarkably clear picture of the everyday circumstances, occupations, and ideals of the Aegean folk at the height of their true prosperity.” Buell agrees: “When most people think of Minoan archaeology they think in terms of the palaces as these monolithic elements devoid of settlements, but at Gournia we have the settlement and the palace, and that’s so important.” [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2015]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024