Home | Category: Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe / Bronze Age Europe

NEOLITHIC AND BRONZE AGE GERMANY AND CENTRAL EUROPE

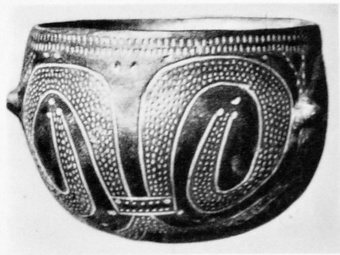

The Linear Pottery culture (LBK) is a major archaeological horizon of the European Neolithic period, flourishing from around 5500 to 4500 B.C.. Derived from the German name Linearbandkeramik, it is also known as the Linear Band Ware, Linear Ware, Linear Ceramics or Incised Ware culture. Most evidence of the culture has been found on the middle Danube, the upper and middle Elbe, and the upper and middle Rhine regions. The term "Linear Band Ware" is derived from the linear decorative techniques on the culture’s pottery. The Stroked Pottery culture flourished between 4900 B.C. and 4400 B.C. These people made pottery with stroked markings and built circular structures called roundels in the Bohemian region of the Czech Republic, [Source: Wikipedia]

The earliest evidence of cheese-making dates to 5500 B.C. is in Kuyavia, Poland. Archaeologists have found long house in Germany dated to 5000 B.C. The Goseck Circle, made of wooden palisades, in Germany, dates to 4900 B.C. The mass grave at Talheim in southern Germany is one of the earliest known sites in the archaeological record that shows evidence of organised violence — in this case among various Linear Pottery culture tribes. Detmerode in Wolfsburg, Germany was the site of Neolithic rituals.

From around 5000 to 3000 B.C. copper started being used first in Southeast Europe, then in Eastern Europe, and Central Europe. The most well-known European Copper Age figure is Otzi, the Iceman, who roamed northern Italy and Austria between some time between 3350 and 3105 B.C., From c. 3500 onwards, there was an influx of people into Eastern Europe from the Pontic-Caspian steppe (Yamnaya culture), creating a plural complex known as Sredny Stog culture.

Important Bronze Age sites in Central Europe include 1) Biskupin in Poland; 2) in Nebra Germany; 3) Zug-Sumpf in Zug, Switzerland and the 4) Vráble in Slovakia. In Central Europe, the early Bronze Age Unetice culture (2300–1600 B.C.) includes numerous smaller groups like the Straubingen, Adlerberg and Hatvan cultures. Some very rich burials, such as the one located at Leubingen (today part of Sömmerda) with grave gifts crafted from gold, point to an increase of social stratification already present in the Unetice culture. All in all, cemeteries of this period are rare and of small size. The Unetice culture is followed by the middle Bronze Age (1600–1200 B.C.) Tumulus culture, which is characterized by inhumation burials in tumuli (barrows). The late Bronze Age Urnfield culture (1300–750 B.C.) is characterized by cremation burials. It includes the Lusatian culture in eastern Germany and Poland (1300–500 B.C.) that continues into the Iron Age. The Central European Bronze Age is followed by the Iron Age Hallstatt culture (800–450 B.C.).

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Dolní Vestonice–Pavlov: Explaining Paleolithic Settlements in Central Europe”

by Jirí A. Svoboda Amazon.com;

“The Early Neolithic of Northern Europe: New Approaches to Migration, Movement and Social Connection” by Daniela Hofmann, Vicki Cummings, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“Woodland in the Neolithic of Northern Europe: The Forest as Ancestor” by Gordon Noble (2017) Amazon.com;

“Monuments in the Making: Raising the Great Dolmens in Early Neolithic Northern Europe” by Vicki Cummings and Colin Richards (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Life and Journey of Neolithic Copper Objects: Transformations of the Neuenkirchen Hoard, North-East Germany (3800 BCE) by Henry Skorna (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings” by Jean Manco (2016) Amazon.com;

“Northern Archaeology and Cosmology: A Relational View” by Vesa-Pekka Herva, Antti Lahelma Amazon.com;

“Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic: Relations and Descent” by Alasdair Whittle, Joshua Pollard (2023) Amazon.com;

“Key to Northwest European Origins” by Raymond F McNair (2012) Amazon.com;

“The First Farmers of Central Europe: Diversity in LBK Lifeways” by Penny Bickle, Alasdair Whittle Amazon.com;

“Seeking the First Farmers in Western Sjælland, Denmark: The Archaeology of the Transition to Agriculture in Northern Europe” by T. Douglas Price (2022) Amazon.com;

“TRB Culture: The First Farmers of the North European Plain” by Magdelina S. Midgeley (1992) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Northern Europe” by H.R. Ellis Davidson (1965) Amazon.com;

“The Earliest Europeans: A Year in the Life: Survival Strategies in the Lower Palaeolithic (Oxbow Insights in Archaeology) by Robert Hosfield (2020) Amazon.com;

“First Migrants: Ancient Migration in Global Perspective” by Peter Bellwood Amazon.com;

“Foragers and Farmers: Population Interaction and Agricultural Expansion in Prehistoric Europe” by Susan A. Gregg (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Transition and the Genetics of Populations in Europe (Princeton Legacy Library)” by Albert J. Ammerman and L L Cavalli-sforza (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Mesolithic Europe” by Liv Nilsson Stutz, Rita Peyroteo Stjerna, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“Mesolithic Europe” by Geoff Bailey and Penny Spikins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe” by Chris Fowler, Jan Harding, Daniela Hofmann (2015) Amazon.com;

“European Societies in the Bronze Age” by A. F. Harding (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age” by Anthony Harding and Harry Fokkens (2020) Amazon.com;

“Organizing Bronze Age Societies: The Mediterranean, Central Europe, and Scandanavia Compared” by Timothy Earle, Kristian Kristiansen Amazon.com;

Cremated 'Bog Bones' Found at 10,000-Year-Old Hazelnut Roasting Site in Germany

In 2022, archaeologists announced that they unearthed 10,000-year-old cremated bones at a Stone Age lakeside campsite that was used for spearing fish and roasting hazelnuts in northern Germany. The site is the earliest known burial in northern Germany, and the discovery marks the first time human remains have been found at Duvensee bog in the Schleswig-Holstein region, where dozens of campsites from the Mesolithic era or Middle Stone Age (roughly between 15,000 and 5,000 years ago) have been found. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, October 22, 2022]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Hazelnuts were a big attraction in the area because Mesolithic people could gather and roast them, Harald Lübke, an archaeologist at the Center for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, an agency of the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation, told Live Science. The campsites changed over time, the research shows. "In the beginning, we have only small hazelnut roasting hearths, and in the later sites, they become much bigger" — possibly a consequence of hazel trees becoming more widespread as the environment changed.

The first sites investigated by Bokelmann in the 1980s were on islands that would have been near the western shore of the lake, which has completely silted up over the last 8,000 years or so, and formed a peat bog, called a "moor" in Germany. Archaeologists have discovered mats made of bark for sitting on the damp soil, pieces of worked flint, and the remains of many Mesolithic fireplaces for roasting hazelnuts, but they haven't unearthed any burials at the island sites. "Maybe they didn't bury people on the islands but only at the sites on the lake border, which seem to have had a different kind of function," Lübke said.

Unlike during the later Mesolithic era, when specific areas were set aside for the burial of the dead, at this time it seemed the dead were buried near where they died, he said. Significantly, the body was cremated before its burial at the Duvensee site, like other burials of approximately the same age near Hammelev in southern Denmark, which is about 120 miles (195 kilometers) to the north. Only pieces of the largest bones were left after the cremation, and it's not clear if they were wrapped in hide or bark before they were buried. In any case, "burning the body seems to be a central part of burial rituals at this time," Lübke said.

The Duvensee bog is among the most important archaeological regions in northern Europe; dozens of Mesolithic sites have been found there since 1923, and most of them since the 1980s. As well as roasting hazelnuts and burning bodies — both of which are activities utilizing fire — Mesolithic people used the lakeside campgrounds for spearing fish, according to the discovery of several bone points crafted for that purpose that were found at the site. Flint fragments also have been found throughout the area, although flint doesn't occur naturally there, suggesting that Mesolithic people repaired their tools and hunting weapons in this place during the annual hazelnut harvest in the fall, Lübke said.

Northern Europeans Built Fine Wells But Were Slow to Adopt Farming

According to Archaeology magazine: Part of an early Neolithic well was uncovered during road construction in East Bohemia near the town of Ostrov in the Czech Republic: Researchers were impressed by the quality of its timber framing, especially given the fact that it was built and shaped using only stone or bone tools. Tree-ring dating has indicated that the trees used for the well’s construction were felled in 5256 or 5255 B.C., making it the oldest wooden architectural structure ever discovered in Europe. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

In 2015, New York University reported: “According to a team of researchers, northern Europeans in the Neolithic period initially rejected the practice of farming, which was otherwise spreading throughout the continent. Their findings offer a new wrinkle in the history of a major economic revolution that moved civilizations away from foraging and hunting as a means for survival. “This discovery goes beyond farming,” explains Solange Rigaud, the study’s lead author and a researcher at the Center for International Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences (CIRHUS) in New York City. [Source: New York University, April 8, 2015]

“It also reveals two different cultural trajectories that took place in Europe thousands of years ago, with southern and central regions advancing in many ways and northern regions maintaining their traditions.” CIRHUS is a collaborative arrangement between France’s National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and New York University. The study, whose other authors include Francesco d’Errico, a professor at CNRS and Norway’s University of Bergen, and Marian Vanhaeren, a professor at CNRS, appears in the journal PLOS ONE.

“In order to study these developments, the researchers focused on the adoption or rejection of ornaments—certain types of beads or bracelets worn by different populations. This approach is suitable for understanding the spread of specific practices—previous scholarship has shown a link between the embrace of survival methods and the adoption of particular ornaments. However, the PLOS ONE study marks the first time researchers have used ornaments to trace the adoption of farming in this part of the world during the Early Neolithic period (8,000-5,000 B.C.).

See Separate Article: SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE WITHIN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

Corded Ware Culture

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic:“About 5,400 years ago, everything changed. All across Europe, thriving Neolithic settlements shrank or disappeared altogether. The dramatic decline has puzzled archaeologists for decades. “There’s less stuff, less material, less people, less sites,” Krause says. “Without some major event, it’s hard to explain.” But there’s no sign of mass conflict or war. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“After a 500-year gap, the population seemed to grow again, but something was very different. In southeastern Europe, the villages and egalitarian cemeteries of the Neolithic were replaced by imposing grave mounds covering lone adult men. Farther north, from Russia to the Rhine, a new culture sprang up, called Corded Ware after its pottery, which was decorated by pressing string into wet clay.

“Corded Ware burials are so recognizable, archaeologists rarely need to bother with radiocarbon dating. Almost invariably, men were buried lying on their right side and women lying on their left, both with their legs curled up and their faces pointed south. In some of the Halle warehouse’s graves, women clutch purses and bags hung with canine teeth from dozens of dogs; men have stone battle-axes. In one grave, neatly contained in a wooden crate on the concrete floor of the warehouse, a woman and child are buried together.

See Separate Article: MIGRATION OF PEOPLE TO STONE AGE EUROPE (45,000 TO 5,000 YEARS AGO) europe.factsanddetails.com

Arrival of the Yamnaya People

The Yamnaya culture, the source of Indo-European languages had a profound impact on Central Europe and Eurasia as a whole. Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: On what are now the steppes of southern Russia and eastern Ukraine, a group of nomads called the Yamnaya, some of the first people in the world to ride horses, had mastered the wheel and were building wagons and following herds of cattle across the grasslands. They built few permanent settlements. But they buried their most prominent men with bronze and silver ornaments in mighty grave mounds that still dot the steppes. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

By 2800 B.C, archaeological excavations show, the Yamnaya had begun moving west, probably looking for greener pastures. A mound near Žabalj is the westernmost Yamnaya grave found so far. But genetic evidence, Harvard’s David Reich and others say, shows that many Corded Ware people were, to a large extent, their descendants. Like those Corded Ware skeletons, the Yamnaya shared distant kinship with Native Americans — whose ancestors hailed from farther east, in Siberia.

“Within a few centuries, other people with a significant amount of Yamnaya DNA had spread as far as the British Isles. In Britain and some other places, hardly any of the farmers who already lived in Europe survived the onslaught from the east. In what is now Germany, “there’s a 70 percent to possibly 100 percent replacement of the local population,” Reich says. “Something very dramatic happens 4,500 years ago.”

See Separate Article: YAMNAYA CULTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

7,000-Year-Old Roundel Structure near Prague

The Vinoř roundel near Prague is among the 'oldest evidence of architecture' in Europe. At 7,000 years old it is older than Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids b a few thousand years. A late Neolithic, or New Stone Age, farming community may have gathered in the circular building, although its purpose is unknown. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, September 21, 2022]

Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: The excavated roundel is large — about 180 feet (55 meters) in diameter, or about as long as the Leaning Tower of Pisa is tall, Radio Prague International reported. And while "it is too early to say anything about the people building this roundel," it's clear that they were part of the Stroked Pottery culture, which flourished between 4900 B.C. and 4400 B.C., Jaroslav Řídký, a spokesperson for the Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences (IAP) and an expert on the Czech Republic's roundels, told Live Science.

Miroslav Kraus, director of the roundel excavation in the district of Vinoř on behalf of the IAP, said that revealing the structure could give them a clue about the use of the building. Researchers first learned about the Vinoř roundel's existence in the 1980s, when construction workers were laying gas and water pipelines, according to Radio Prague International, but the current dig has revealed the structure's entirety for the first time. So far, his team has recovered pottery fragments, animal bones and stone tools in the ditch fill, according to Řídký. Carbon-dating organic remains from this roundel excavation could help the team pinpoint the date of the structure's construction and possibly link it with a Neolithic settlement discovered nearby.

Roundels and the Stroked Pottery Culture

Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: The people who made Stroked Pottery ware are known for building other roundels in the Bohemian region of the Czech Republic, Řídký said. Their sedentary farming villages — located at the intersection of contemporary Poland, eastern Germany and the northern Czech Republic — consisted of several longhouses, which were large, rectangular structures that held 20 to 30 people each. But the "knowledge of building of roundels crossed the borders of several archaeological cultures," Řídký noted. "Different communities built roundels across central Europe." [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, September 21, 2022]

Roundels were not well-known ancient features until a few decades ago, when aerial and drone photography became a key part of the archaeological tool kit. But now, archaeologists know that "roundels are the oldest evidence of architecture in the whole of Europe," Řídký told Radio Prague International. Viewed from above, roundels consist of one or more wide, circular ditches with several gaps that functioned as entrances. The inner part of each roundel was likely lined with wooden poles, perhaps with mud plastering the gaps, according to Radio Prague International. Hundreds of these circular earthworks have been found throughout central Europe, but they all date to a span of just two or three centuries. While their popularity in the late Neolithic is clear, their function is still in question.

In 1991, the earliest known roundel was found in Germany, also corresponding to the Stroked Pottery culture. Called the Goseck Circle, it is 246 feet (75 m) in diameter and had a double wooden palisade and three entrances. Because two of the entrances correspond with sunrise and sunset during the winter and summer solstices, one interpretation of the Goseck Circle is that it functioned as an observatory or calendar of sorts, according to a 2012 study in the journal Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association.

Řídký preferred a more general interpretation of the Vinoř structure, noting that "roundels probably combined several functions, the most important being socio-ritual," he told Live Science. It is likely that roundels were built for gatherings of a large number of people, perhaps to commemorate events important to them as a community, such as rites of passage, astronomical phenomena or economic exchange.

Given that the people who built roundels had only stone tools to work with, these roundels' sizes are quite impressive — most commonly, about 200 feet (60 m) in diameter, or half the length of a football field. But little is known about the people themselves, as very few burials have been found that could provide more information about their lives seven millennia ago.

After three centuries of popularity, roundels suddenly disappeared from the archaeological record around 4600 B.C. Archaeologists do not yet know why the roundels were abandoned. But considering over one-quarter of all roundels found to date are located in the Czech Republic, future research similar to the excavation at Vinoř may eventually help solve the mystery of the roundels.

See Separate Article: GERMANY'S STONEHENGE, AND NEOLITHIC ROUNDELS AND MEGAFORTS europe.factsanddetails.com

4,200-Year-Old “Zombie” Grave in Germany

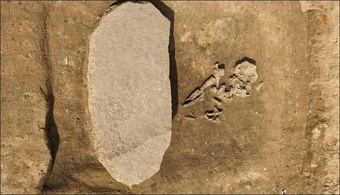

Tim Newcomb wrote in Popular Mechanics: The grave makers of the Early Bronze Age had their own strategies for keeping the dead... well... dead. In fear of “revenant” people — think zombies — recovering from death to torment those still alive, the people burying the dead would often employ efforts to keep bodies more securely confined to their graves. [Source: Tim Newcomb, Popular Mechanics, May 1, 2024]

One such “zombie grave” was recently found in Oppin, Germany, according to a Facebook post from the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt. The strategy used for keeping this body in place was a stone over 3 feet long and about 1.6 feet wide pinning down the legs, which belonged to a middle-aged man who would have been burried in the tomb roughly 4,200 years ago. At four inches thick, the stone was no small weight. “It must be assumed that the stone was placed there for a reason,” a translated statement from the state office read, “possibly to hold the dead in the grave and preventing it from coming back.”

The state office believes that the tomb was laid during the time of the Bell Beaker culture, as it was found near other cultural discoveries. This culture was present near the end of the Neolithic period and start of the Early Bronze Age (roughly 2,800 B.C.), and while there is little recorded about the Bell Beaker culture, the find could provide deeper insight into the superstitions of the people.

“We know that already in the Stone Age people were afraid of revenants,” Susanne Friederich, an archaeologist with the state office and project manager for the excavations told Newsweek. “Back then, people believed that dead people sometimes tried to free themselves from their graves. Sometimes, the dead were laid on their stomachs. If the dead lies on his stomach, he burrows deeper and deeper instead of reaching the surface.” Some graves even showed that burying the dead on their stomach wasn’t considered enough, and featured the addition of a lance through the torso used to help secure the body in place. The tomb was found to be empty except for the man buried inside, who is believed to have been aged between 40 and 60 when he died, and was found in a crouched position laid on his side. The oversized stone was placed on his legs.

Bronze Age Jewelry from Poland Was Part of a Water Burial Ritual

A collection of more than 550 pieces of metal jewelry and human remains found at a dry lake-bed site in Poland were part of an ancient water burial ritual. Known as Papowo Biskupie, the dried-out lake bed site was occupied from roughly 1200 to 450 B.C. by the Chełmno group, a community from the larger Lusatian culture that lived in northern Europe during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, according to a study published on January 24, 2024 in the journal Antiquity. The Lusatians are best known for their ritual depositions of metal hoards in bodies of water. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, January 25, 2024]

"The scale of metal consumption at the site is extraordinary," study co-author Łukasz Kowalski, a postdoctoral researcher of archaeology at the AGH University of Science and Technology of Krakow, told Live Science. "Until now, we thought that metal was a weak partner in the social and ritual strategies of the Chełmno group, in contrast with the metal-hoarding madness [practiced by the other Lusatians]."

Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: The discovery of this cache of metal jewelry — which includes a variety of arm and neck ornaments, as well as a multistrand necklace with oval and tubular beads surrounding a swallowtail-like pendant — has led researchers to change their viewpoint, according to a statement. "Our findings reflect the increasing role of metal in social and ritual life of [the Chełmno group], resulting in a shift from the deposition of human remains to metal offerings in the local wetland landscape," Kowalski said.

The researchers concluded that many of the metal artifacts were created by members of the local community. But some, including one of the beads in the necklace, were crafted using outsourced materials. "The bead is made of low-magnesium glass that was sourced from the Eastern Mediterranean region," Kowalski said. "This increases the use of evidence that power-elites of the Chełmno group became parties to a metal trading network that connected much of the European continent in the 1st millennium B.C." As part of the study, the researchers created a hypothetical model of a Chełmno woman wearing some of the metal jewelry.

In addition to the jewelry, the archaeologists unearthed the skeletal remains of at least 33 individuals at the lake bed. However, radiocarbon dating revealed that the human remains were buried before the metal deposition, which offers further evidence that the Chełmno group's "belief system later came into line with the rest of the region," according to the statement. "Our discovery opens a new window for exploring the social and ritual practices of the Chełmno group and reflects the complex interplay between deposition of human remains and metal objects in wetlands," Kowalski said. "This discovery may signal how metal and human depositions could be used to regulate social relations in the Chełmno group and to demonstrate their local identity."

Nebra Sky Disc — Bronze Age Map of the Stars

A 3,600-year-old star map discovered in the Harz mountains near the town of Goseck in central-eastern Germany contains the oldest known depiction of the night sky and may have served as an agricultural and spiritual calendar. More sophisticated than Stonehenge and predating Greek astronomy by more than 1,000 years, it has a depiction of the Pleiades which disappears in central Germany in early March, an event that has traditionally marked the beginning of the planting season, and may have been used to predict lunar eclipses. [Source: Harold Meller, National Geographic, January 2004]

The star map, known as the Nebra Sky Diss of , is a bronze disk about the size of a dinner plate. It contains a gold sun and moon set against a field of gold stars and tracks the sun's movements along the horizon. Serving as kind of portable Stonehenge, it allowed users to match local geographical features such as Brocken, the highest peak in the Harz mountains with celestial events.

When the sun part of the disk is oriented to the west one end points to Brocken and sunset in the summer solstice and the other end point to sunset on the winter solstice. Frost in the region typically ended when the sun fell behind another prominent feature, Kyffhauser. The disk also seemed to have religion significance. One of the curved gold objects is inscribed with with what appear to be oars; and it appeared to be a celestial night ship like those found in ancient Egypt.

The star map was found in a stone mound surrounded the 75-meter-in-diameter berm on Mittelberg hill above the farming village of Wangen in the Unstrut valley near the town of Nebra. The copper came from the Austrian Alps and the gold came from Transylvania. In the Bronze Age central-eastern Germany was a major transportation hub and trading center. Deposits of salt and copper were available locally. Tin and gold were brought in by traders (tin and copper are used to make bronze).

The site was discovered by local people employed by looters who tried to sell the disk on the black market. After it traded hands several times smuggler trying to sell it were caught in Switzerland in a sting operation using a German archaeologists who offered to pay $400,000 for the disk and some bronze swords and other objects.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except the the roundel from Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences

Text Sources: National Geographic, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024