Home | Category: First Modern Humans / Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe

THREE WAVES OF ANCIENT MIGRANTS TO EUROPE

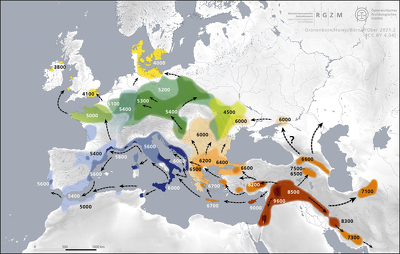

There were three waves of immigrants that settled prehistoric Europe. 1) Hunter-gatherers, who were modern humans, whose ancestors evolved in Africa, reached Europe some 45,000 years ago; 2) Neolithic farmers from present-day Turkey had joined them in southern Europe by around 6000 B.C. and pushed deeper into the continent as time went on; and 3) the Yamnaya culture that swept in from Russia around 3300 B.C. and relatively quickly made their presence known. Most Europeans today have DNA from all three groups. Modern Europeans Yamnaya bloodlines are strongest in the north, those of Neolithic farmers in the south.

The early settlers were widely scattered. They kept their distance when Neolithic farmers first arrived. Agriculture began around 9500 B.C. Neolithic farmers brought wheat, sheep, cattle — and their own DNA — to most of Europe by 4000 B.C. The mastery of horses and wagons by the Yamnaya culture introduced a new mobile lifestyle to Europe. Before the arrival of the Yamnaya, Neolithic farmer DNA had largely replaced that of hunter-gatherers. By 1000 B.C. Yamnaya DNA could be found all across Europe.

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic:“Scientific “findings suggest that the continent has been a melting pot since the Ice Age. Europeans living today, in whatever country, are a varying mix of ancient bloodlines hailing from Africa, the Middle East, and the Russian steppe. DNA recovered from ancient teeth and bones lets researchers understand population shifts over time. As the cost of sequencing DNA has plummeted, scientists at labs like the one in Jena, Germany, have been able to unravel patterns of past human migration. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“All Europeans today are a mix. The genetic recipe for a typical European would be roughly equal parts Yamnaya and Anatolian farmer, with a much smaller dollop of African hunter-gatherer. But the average conceals large regional variations: more “eastern cowboy” genes in Scandinavia, more farmer ones in Spain and Italy, and significant chunks of hunter-gatherer DNA in the Baltics and eastern Europe. “To me, the new results from DNA are undermining the nationalist paradigm that we have always lived here and not mixed with other people,” Gothenburg’s Kristiansen says. “There’s no such thing as a Dane or a Swede or a German.” Instead, “we’re all Russians, all Africans.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY EUROPEANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST MODERN HUMANS IN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE TO EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

INDO-EUROPEANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

YAMNAYA CULTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Earliest Europeans: A Year in the Life: Survival Strategies in the Lower Palaeolithic (Oxbow Insights in Archaeology) by Robert Hosfield (2020) Amazon.com;

“Earliest Italy: An Overview of the Italian Paleolithic and Mesolithic by Margherita Mussi Amazon.com;

“First Migrants: Ancient Migration in Global Perspective” by Peter Bellwood Amazon.com;

“Continuity and Discontinuity in the Peopling of Europe" by Silvana Condemi, Gerd-Christian Weniger (2011) Amazon.com;

“European Origin of Homo Sapiens: Atapuerca” by Santiago Sevilla Amazon.com

“In search of Homo heidelbergensis: How Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and hobbits emerged by Christopher Seddon Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia” by John G Fleagle, John J. Shea, Editors (2010), Amazon.com;

“The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archeology of the Levant and Beyond by Yoshihiro Nishiaki, Takeru Akazawa, Editors Amazon.com;

“The Seven Daughters of Eve: The Science That Reveals Our Genetic Ancestry”

by Bryan Sykes (2002) Amazon.com;

Amazon.com;

“The Global Prehistory of Human Migration” by Immanuel Ness and Peter Bellwood (2014) Amazon.com;

“Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World” by Stephen Oppenheimer Amazon.com;

“The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey” (Princeton Science Library) by Spencer Wells (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey Out of Africa” by Stephen Oppenheimer (2004) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

Genetics and Evidence of Ancient Migrations to Europe

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: The evidence on the migrations of peoples to Europe “comes from archaeological artifacts, from the analysis of ancient teeth and bones, and from linguistics. But above all it comes from the new field of paleogenetics. Since the late 2000s it has become possible to sequence the entire genome of humans who lived tens of millennia ago. Technical advances in just the past few years have made it cheap and efficient to do so; a well-preserved bit of skeleton can now be sequenced for around $500. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“The result has been an explosion of new information that is transforming archaeology. In 2018 alone, the genomes of more than a thousand prehistoric humans were determined, mostly from bones dug up years ago and preserved in museums and archaeological labs. In the process any notion of European genetic purity has been swept away on a tide of powdered bone.

“Analysis of ancient genomes provides the equivalent of the personal DNA testing kits available today, but for people who died long before humans invented writing, the wheel, or pottery. The genetic information is startlingly complete: Everything from hair and eye color to the inability to digest milk can be determined from a thousandth of an ounce of bone or tooth. And like personal DNA tests, the results reveal clues to the identities and origins of ancient humans’ ancestors — and thus to ancient migrations.

“Three major movements of people, it now seems clear, shaped the course of European prehistory. Immigrants brought art and music, farming and cities, domesticated horses and the wheel. They introduced the Indo-European languages spoken across much of the continent today. They may have even brought the plague. The last major contributors to western and central Europe’s genetic makeup — the last of the first Europeans, so to speak — arrived from the Russian steppe as Stonehenge was being built, nearly 5,000 years ago. They finished the job.

“In an era of debate over migration and borders, the science shows that Europe is a continent of immigrants and always has been. “The people who live in a place today are not the descendants of people who lived there long ago,” says Harvard University paleogeneticist David Reich. “There are no indigenous people — anyone who hearkens back to racial purity is confronted with the meaninglessness of the concept.”

First Wave of Migrants to Europe — the Hunter Gathers

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: Thirty-two years ago the study of the DNA of living humans helped establish that we all share a family tree and a primordial migration story: All people outside Africa are descended from ancestors who left that continent more than 60,000 years ago. About 45,000 years ago, those first modern humans ventured into Europe, having made their way up through the Middle East. Their own DNA suggests they had dark skin and perhaps light eyes. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“Europe then was a forbidding place. Mile-thick ice sheets covered parts of the continent. Where there was enough warmth, there was wildlife. There were also other humans, but not like us: Neanderthals, whose own ancestors had wandered out of Africa hundreds of thousands of years earlier, had already adapted to the cold and harsh conditions.

“The first modern Europeans lived as hunters and gatherers in small, nomadic bands. They followed the rivers, edging along the Danube from its mouth on the Black Sea deep into western and central Europe. For millennia, they made little impact. Their DNA indicates they mixed with the Neanderthals — who, within 5,000 years, were gone. Today about 2 percent of a typical European’s genome consists of Neanderthal DNA. A typical African has none.

“As Europe was gripped by the Ice Age, the modern humans hung on in the ice-free south, adapting to the cold climate. Around 27,000 years ago, there may have been as few as a thousand of them, according to some population estimates. They subsisted on large mammals such as mammoths, horses, reindeer, and aurochs — the ancestors of modern cattle. In the caves where they sheltered, they left behind spectacular paintings and engravings of their prey.

Migration of the First Modern Humans (Hunter Gathers) to Europe

Our species, Homo sapiens, arose in Africa more than 300,000 years ago, and anatomically modern humans emerged at least 195,000 years ago. Evidence for the first waves of modern humans outside Africa dates back at least 194,000 years to Israel, and possibly 210,000 years to Greece. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, May 4, 2023]

It was long thought that modern humans reached Europe around 45,000 years ago but newly analyzed tools from the Stone Age have challenge this idea. Now, evidence suggests that modern humans ventured into Europe in three waves between 54,000 and 42,000 years ago, according to a 2023 study.

It was originally believed that the first modern humans in Europe arrived via the Middle East or North Africa, possibly crossing a land bridge between Tunisia, Sicily and Italy or the Strait of Gibraltar but genetic evidence indicates that more likely they came from Asia. The DNA of western Eurasians is more like people from India than those from Africa. The conclusion that one draws is that Europe was populated by people who migrated across western Asia and the Balkans into Europe between 40,000 and 35,000 years ago.

It is widely assumed that cold, inhospitable weather prevented modern humans from entering Europe earlier than they did. By 35,000 years they were well established and quickly dominated and replaced Neanderthals that began declining about the same time modern humans arrived. The population shrank a great deal during the Ice Age 20,000 years ago then rebounded. The Ice Age nearly wiped out humans.

See Separate Article: FIRST MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

First Modern Humans in Europe

Modern humans are believed to have reached Europe in significant numbers by around 45,000 years ago, but some bold pioneers may have show up long before that (See "210,000-Year-Old Modern Human Skull in Greece").

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: For years, the oldest confirmed signs of modern humans in Europe were teeth about 42,000 years old that archaeologists had unearthed in Italy and Bulgaria. These ancient groups were likely Protoaurignacians — the earliest members of the Aurignacians, the first known hunter-gatherer culture in Europe. However, a 2022 study revealed that a tooth found in the site of Grotte Mandrin in southern France's Rhône Valley suggested that modern humans lived there about 54,000 years ago, a 2022 study found. This suggested Europe was home to modern humans about 10,000 years earlier than previously thought. In the 2022 study, scientists linked this fossil tooth with stone artifacts that scientists previously dubbed Neronian, after the nearby Grotte de Néron site. Neronian tools include tiny flint arrowheads or spearpoints and are unlike anything else found in Europe from that time. [Source:Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, May 4, 2023]

It is widely assumed that cold, inhospitable weather prevented modern humans from entering Europe earlier than they did. By 35,000 years they were well established and quickly dominated and replaced Neanderthals that began declining about the same time modern humans arrived. The population shrank a great deal during the Ice Age 20,000 years ago then rebounded. The Ice Age nearly wiped out humans.

DNA studies indicate that 6 percent of Europeans arose from the first people who arrived about 45,000 years ago. These people are more numerous in certain places like the Basque region and remote parts of Scandinavia. Another 80 percent arrived 30,000 to 20,000 years ago before the peak of glaciation. The remaining 10 percent arrived about 10,000 years ago.

See Separate Article: FIRST MODERN HUMANS IN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ice Age Migrations, Survival and Death

In March 2023, researchers published their analysis of genome data in Nature from 356 hunter-gatherers who lived in the region between 35,000 and 5,000 years ago, a period of time that included the Ice Age's coldest interval between 25,000 and 19,000 years ago. According to Reuters: This enabled them to decipher prehistoric Europe's population dynamics, including the movement of groups of people and some key physical traits.While some populations hunkered down and survived in relatively warmer parts of Europe, including France, Spain and Portugal, others died out on the Italian peninsula, the study showed. It also provided insight into the advent of characteristics such as light skin and blue eyes in Europeans. "It is the largest ancient genomic dataset of European hunter-gatherers ever produced," said paleogeneticist Cosimo Posth of the University of Tübingen in Germany, lead author of the study "It refreshes our knowledge of how human beings survived the Ice Age," added paleogeneticist and study co-author He Yu of Peking University in China.[Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, March 2, 2023]

Various groups of hunter-gatherers roamed the European landscape, hunted large mammals including woolly mammoths, woolly rhinos and reindeer, and collected edible plants. During the Ice Age's coldest period, known as the Last Glacial Maximum, ice sheets called continental glaciers covered half of Europe, with much of the rest in tundra conditions with frozen subsoil. The only people who survived this harshest period in Europe were hunter-gatherers who had found refuge in portions of France and the Iberian peninsula, the study found. The Italian peninsula, previously thought to have been a refuge for people during this period, was just the opposite - all its inhabitants perished. "It is a big surprise that humans went extinct on the Italian peninsula," said study senior author Johannes Krause, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

That region was repopulated around 19,000 years ago by hunter-gatherers from the Balkans, who subsequently expanded throughout Europe and by around 14,500 years ago had replaced everyone who had lived there, the researchers found. "From around 14,000 to 13,000 years ago, the climate became warmer and most parts of Europe gradually turned into forest, similar to today," Yu said.

The Homo sapiens individuals who entered Europe after a migration out of Africa were dark-skinned. The genome data showed a change toward light skin among people in Europe between 14,000 and 8,000 years ago that accelerated with the subsequent spread of farming on the continent. Certain traits of Western European hunter-gatherers, known for blue eyes and dark skin, differed from their counterparts in Eastern Europe, who had light skin and dark eyes. Those two populations started to interbreed around 8,000 years ago only after the first farmers arrived in Europe from Anatolia - modern Turkey - and pushed all the hunter-gatherers northward.

The genome data showed that populations associated with what is called the Gravettian culture dating to around 34,000 to 26,000 years ago - known for certain types of stone tools, cave paintings and small sculptures called "Venus" figurines - were not in fact homogeneous. Instead, there were two largely unrelated populations sharing cultural attributes. "A big surprise for me," Yu said, "is the fact that Gravettian populations carried two genetically distinct ancestries and that one of those disappeared from Europe."

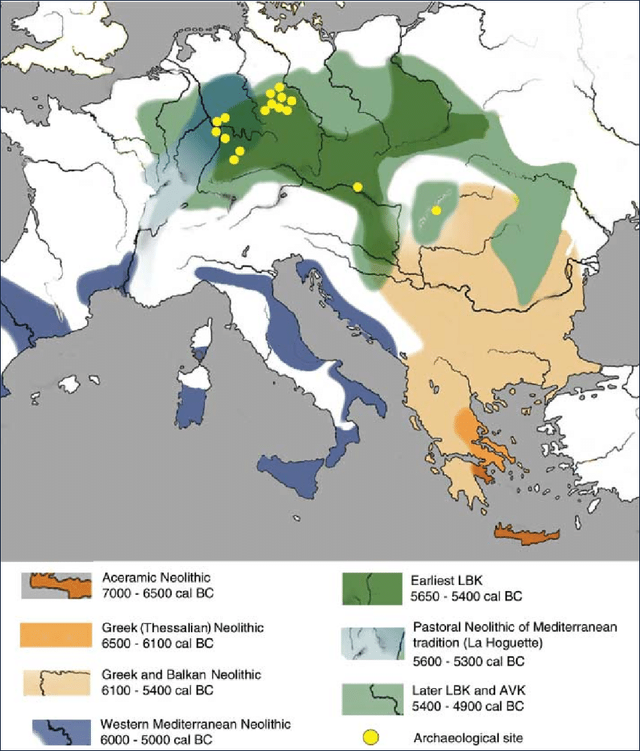

Second Wave of Migrants to Europe — Farmers from Anatolia

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: The Konya Plain in central Anatolia is modern Turkey’s breadbasket, a fertile expanse where you can see rainstorms blotting out mountains on the horizon long before they begin spattering the dust around you. It has been home to farmers, says University of Liverpool archaeologist Douglas Baird, since the first days of farming. For more than a decade Baird has been excavating a prehistoric village here called Boncuklu. It’s a place where people began planting small plots of emmer and einkorn, two ancient forms of wheat, and probably herding small flocks of sheep and goats, some 10,300 years ago, near the dawn of the Neolithic period. Within a thousand years the Neolithic revolution, as it’s called, spread north through Anatolia and into southeastern Europe. By about 6,000 years ago, there were farmers and herders all across Europe. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“Bones and artifacts some 7,700 years old found at Aktopraklik, a Neolithic village in northwestern Turkey, offer clues to the early days of agriculture. DNA extracted from the skulls of people buried here has helped researchers trace the spread of early farmers into Europe. A grindstone from Aktopraklik testifies to grain farming. A ceramic sherd bears an image of wheat. A terra-cotta statuette of a woman may symbolize fertility.

“Over the centuries the descendants of the migrants from Anatolia pushed along the Danube deep into the heart of the continent. Others traveled along the Mediterranean by boat, colonizing islands such as Sardinia and Sicily and settling southern Europe as far as Portugal. From Boncuklu to Britain, the Anatolian genetic signature is found wherever farming first appears.

“Those Neolithic farmers mostly had light skin and dark eyes — the opposite of many of the hunter-gatherers with whom they now lived side by side. “They looked different, spoke different languages … had different diets,” says Hartwick College archaeologist David Anthony. “For the most part, they stayed separate.”

“Across Europe, this creeping first contact was standoffish, sometimes for centuries. There’s little evidence of one group taking up the tools or traditions of the other. Even where the two populations did mingle, intermarriage was rare. “There’s no question they were in contact with each other, but they weren’t exchanging wives or husbands,” Anthony says. “Defying every anthropology course, people were not having sex with each other.” Fear of the other has a long history.

Gathering Evidence About the Migration of Anatolian Farmers to Europe

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “It has long been clear that Europe acquired the practice of farming from Turkey or the Levant, but did it acquire farmers from the same places? The answer isn’t obvious. For decades, many archaeologists thought a whole suite of innovations — farming, but also ceramic pottery, polished stone axes capable of clearing forests, and complicated settlements — was carried into Europe not by migrants but by trade and word of mouth, from one valley to the next, as hunter- gatherers who already lived there adopted the new tools and way of life. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“But DNA evidence from Boncuklu has helped show that migration had a lot more to do with it. The farmers of Boncuklu kept their dead close, burying them in the fetal position under the floors of their houses. Beginning in 2014, Baird sent samples of DNA extracted from skull fragments and teeth from more than a dozen burials to DNA labs in Sweden, Turkey, the U.K., and Germany.

“Many of the samples were too badly degraded after spending millennia in the heat of the Konya Plain to yield much DNA. But then Johannes Krause and his team at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History tested the samples from a handful of petrous bones. The petrous bone is a tiny part of the inner ear, not much bigger than a pinkie tip; it’s also about the densest bone in the body. Researchers have found that it preserves genetic information long after usable DNA has been baked out of the rest of a skeleton. That realization, along with better sequencing machines, has helped drive the explosion in ancient DNA studies.

“The Boncuklu petrous bones paid off: DNA extracted from them was a match for farmers who lived and died centuries later and hundreds of miles to the northwest. That meant early Anatolian farmers had migrated, spreading their genes as well as their lifestyle.

Neolithic Farmers and Hunter-Gatherers Lived Side by Side But Didn’t Mix So Much

A study published in Nature in November 2017, suggests that early farmers who migrated to Europe from the Near East and hunter-gatherers lived side-by-side but didn’t mix so much for century. The farming populations then slowly integrated local hunter-gatherers, showing more assimilation of the hunter-gatherers into the farming populations as time went on. [Source: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Science Daily, November 9. 2017]

The 2017 current study, from an international team including scientists from Harvard Medical School, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, focused on the regional interactions between early farmers and late hunter-gatherer groups across a broad timespan in three locations in Europe: the Iberian Peninsula in the West, the Middle-Elbe-Saale region in north-central Europe, and the fertile lands of the Carpathian Basin (centered in what is now Hungary). The researchers used high-resolution genotyping methods to analyze the genomes of 180 early farmers, 130 of whom are newly reported in this study, from the period of 6000-2200 B.C. to explore the population dynamics during this period.

“We find that the hunter-gatherer admixture varied locally but more importantly differed widely between the three main regions,” says Mark Lipson, a researcher in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School and co-first author of the paper. “This means that local hunter-gatherers were slowly but steadily integrated into early farming communities.” While the percentage of hunter-gatherer heritage never reached very high levels, it did increase over time. This finding suggests the hunter-gatherers were not pushed out or exterminated by the farmers when the farmers first arrived. Rather, the two groups seem to have co-existed with increasing interactions over time. Further, the farmers from each location mixed only with hunter-gatherers from their own region, and not with hunter-gatherers, or farmers, from other areas, suggesting that once settled, they stayed put.

“One novelty of our study is that we can differentiate early European farmers by their specific local hunter-gatherer signature,” adds co-first author Anna Szécsényi-Nagy of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. “Farmers from Spain share hunter-gatherer ancestry with a pre-agricultural individual from La Braña, Spain, whereas farmers from central Europe share more with hunter-gatherers near them, such as an individual from the Loschbour cave in Luxembourg. Similarly, farmers from the Carpathian Basin share more ancestry with local hunter-gatherers from their same region.”

The team also investigated the relative length of time elapsed since the integration events between the populations, using cutting-edge statistical techniques that focus on the breakdown of DNA blocks inherited from a single individual. The method allows scientists to estimate when the populations mixed. Specifically, the team looked at 90 individuals from the Carpathian Basin who lived close in time. The results — which indicate ongoing population transformation and mixture — allowed the team to build the first quantitative model of interactions between hunter-gatherer and farmer groups. “We found that the most probable scenario is an initial, small-scale, admixture pulse between the two populations that was followed by continuous gene flow over many centuries,” says senior lead author David Reich, professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School.

Corded Ware Culture

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic:“About 5,400 years ago, everything changed. All across Europe, thriving Neolithic settlements shrank or disappeared altogether. The dramatic decline has puzzled archaeologists for decades. “There’s less stuff, less material, less people, less sites,” Krause says. “Without some major event, it’s hard to explain.” But there’s no sign of mass conflict or war. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“After a 500-year gap, the population seemed to grow again, but something was very different. In southeastern Europe, the villages and egalitarian cemeteries of the Neolithic were replaced by imposing grave mounds covering lone adult men. Farther north, from Russia to the Rhine, a new culture sprang up, called Corded Ware after its pottery, which was decorated by pressing string into wet clay.

“The State Museum of Prehistory in Halle, Germany, has dozens of Corded Ware graves, including many that were hastily rescued by archaeologists before construction crews went to work. To save time and preserve delicate remains, the graves were removed from the ground in wooden crates, soil and all, and stored in a warehouse for later analysis. Stacked to the ceiling on steel shelves, they’re now a rich resource for geneticists.

“Corded Ware burials are so recognizable, archaeologists rarely need to bother with radiocarbon dating. Almost invariably, men were buried lying on their right side and women lying on their left, both with their legs curled up and their faces pointed south. In some of the Halle warehouse’s graves, women clutch purses and bags hung with canine teeth from dozens of dogs; men have stone battle-axes. In one grave, neatly contained in a wooden crate on the concrete floor of the warehouse, a woman and child are buried together.

“When researchers first analyzed the DNA from some of these graves, they expected the Corded Ware folk would be closely related to Neolithic farmers. Instead, their DNA contained distinctive genes that were new to Europe at the time — but are detectable now in just about every modern European population. Many Corded Ware people turned out to be more closely related to Native Americans than to Neolithic European farmers. That deepened the mystery of who they were.

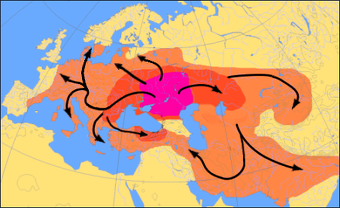

Third Wave of Migrants to Europe — the Yamnaya Culture from Ukraine

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: One bright October morning near the Serbian town of Žabalj, Polish archaeologist Piotr Włodarczak and his colleagues steer their pickup toward a mound erected 4,700 years ago. On the plains flanking the Danube, mounds like this one, a hundred feet across and 10 feet high, provide the only topography. It would have taken weeks or months for prehistoric humans to build each one. It took Włodarczak’s team weeks of digging with a backhoe and shovels to remove the top of the mound. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“Standing on it now, he peels back a tarp to reveal what’s underneath: a rectangular chamber containing the skeleton of a chieftain, lying on his back with his knees bent. Impressions from the reed mats and wood beams that formed the roof of his tomb are still clear in the dark, hard-packed earth. “It’s a change of burial customs around 2800 B.C.,” Włodarczak says, crouching over the skeleton. “People erected mounds on a massive scale, accenting the individuality of people, accenting the role of men, accenting weapons. That’s something new in Europe.”

“It was not new 800 miles to the east, however. On what are now the steppes of southern Russia and eastern Ukraine, a group of nomads called the Yamnaya, some of the first people in the world to ride horses, had mastered the wheel and were building wagons and following herds of cattle across the grasslands. They built few permanent settlements. But they buried their most prominent men with bronze and silver ornaments in mighty grave mounds that still dot the steppes.

By 2800 B.C, archaeological excavations show, the Yamnaya had begun moving west, probably looking for greener pastures. Włodarczak’s mound near Žabalj is the westernmost Yamnaya grave found so far. But genetic evidence, Reich and others say, shows that many Corded Ware people were, to a large extent, their descendants. Like those Corded Ware skeletons, the Yamnaya shared distant kinship with Native Americans — whose ancestors hailed from farther east, in Siberia.

Admixture proportions of Yamnaya populations. A combination of Eastern Hunter Gatherer (EHG), Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (CHG), Anatolian Neolithic and Western Hunter Gatherer (WHG) ancestry

“Within a few centuries, other people with a significant amount of Yamnaya DNA had spread as far as the British Isles. In Britain and some other places, hardly any of the farmers who already lived in Europe survived the onslaught from the east. In what is now Germany, “there’s a 70 percent to possibly 100 percent replacement of the local population,” Reich says. “Something very dramatic happens 4,500 years ago.”

“Until then, farmers had been thriving in Europe for millennia. They had settled from Bulgaria all the way to Ireland, often in complex villages that housed hundreds or even thousands of people. Volker Heyd, an archaeologist at the University of Helsinki, Finland, estimates there were as many as seven million people in Europe in 3000 B.C. In Britain, Neolithic people were constructing Stonehenge.

“To many archaeologists, the idea that a bunch of nomads could replace such an established civilization within a few centuries has seemed implausible. “How the hell would these pastoral, decentralized groups overthrow grounded Neolithic society, even if they had horses and were good warriors?” asks Kristian Kristiansen, an archaeologist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.A clue comes from the teeth of 101 people living on the steppes and farther west in Europe around the time that the Yamnaya’s westward migration began. In seven of the samples, alongside the human DNA, geneticists found the DNA of an early form of Yersinia pestis — the plague microbe that killed roughly half of all Europeans in the 14th century.

See Separate Article: YAMNAYA CULTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except spread of farming across Europe from Researchgate

Text Sources: National Geographic, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024