Home | Category: Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe

SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE WITHIN EUROPE

A study published in Science in April 2012 argues that farming originated in the Near East some 11,000 years ago, and extended over most of Europe by about 6,000 years ago. Associated Press reported: “Scientists analyzed genetic material from bones about 5,000 years old that had been found in Sweden. The bones came from three hunter-gatherers who’d been buried on the island of Gotland, which lies off the Swedish coast south of Stockholm, and a farmer buried less than 250 miles (400 kilometers) away on the mainland. Scientists knew their lifestyles because of artifacts. The two cultures apparently co-existed in the area for more than 1,000 years. [Source: Associated Press, 28 April 2012]

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “Over the centuries the descendants of the migrants from Anatolia pushed along the Danube deep into the heart of the continent. Others traveled along the Mediterranean by boat, colonizing islands such as Sardinia and Sicily and settling southern Europe as far as Portugal. From Boncuklu to Britain, the Anatolian genetic signature is found wherever farming first appears.[Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

“Those Neolithic farmers mostly had light skin and dark eyes — the opposite of many of the hunter-gatherers with whom they now lived side by side. “They looked different, spoke different languages … had different diets,” says Hartwick College archaeologist David Anthony. “For the most part, they stayed separate.”

“Across Europe, this creeping first contact was standoffish, sometimes for centuries. There’s little evidence of one group taking up the tools or traditions of the other. Even where the two populations did mingle, intermarriage was rare. “There’s no question they were in contact with each other, but they weren’t exchanging wives or husbands,” Anthony says. “Defying every anthropology course, people were not having sex with each other.” Fear of the other has a long history.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MIGRATION OF PEOPLE TO STONE AGE EUROPE (45,000 TO 5000 YEARS AGO) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE TO EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The First Farmers of Europe” by Stephen Shennan (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Agriculture in Europe” by I. J. Thorpe (2003) Amazon.com;

“Foragers and Farmers: Population Interaction and Agricultural Expansion in Prehistoric Europe” by Susan A. Gregg (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Early Neolithic in Greece: The First Farming Communities in Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology) by Catherine Perlès (Author), Gerard Monthel (Illustrator) Amazon.com;

“Plant Foods of Greece: A Culinary Journey to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages” by Soultana Maria Valamoti (2023) Amazon.com;

“The First Farmers of Central Europe: Diversity in LBK Lifeways” by Penny Bickle, Alasdair Whittle Amazon.com;

“Seeking the First Farmers in Western Sjælland, Denmark: The Archaeology of the Transition to Agriculture in Northern Europe” by T. Douglas Price (2022) Amazon.com;

“TRB Culture: The First Farmers of the North European Plain” by Magdelina S. Midgeley (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

"First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies" by Peter Bellwood (2004) Amazon.com;

“Birth Gods and Origins Agriculture” by Jacques Cauvin (2008) Amazon.com;

“After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000–5000 BC” by Steven Mithen (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective” by C. Wesley Cowan, Paul Minnis, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Paleopathology at the Origins of Agriculture” by Mark N. Cohen Amazon.com;

“Behavioral Ecology and the Transition to Agriculture” by Douglas J. Kennett and Bruce Winterhalder (2006) Amazon.com;

“Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation” by Ian Kuijt (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Transition and the Genetics of Populations in Europe (Princeton Legacy Library)” by Albert J. Ammerman and L L Cavalli-sforza (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Global Prehistory of Human Migration” by Immanuel Ness and Peter Bellwood (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey” (Princeton Science Library) by Spencer Wells (2017) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

Lepenski Vir, Serbia — Where Early European Farmers and Hunter-Gatherers Met

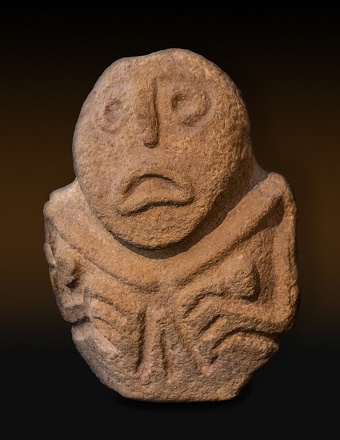

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic:“ “Over millennia, migrating humans have used the Danube River as a highway from the Fertile Crescent into the heart of Europe. In the 1960s Serbian archaeologists uncovered a Mesolithic fishing village nestled in steep cliffs on a bend of the Danube, near one of the river’s narrowest points. Called Lepenski Vir, the site was an elaborate settlement that had housed as many as a hundred people, starting roughly 9,000 years ago. Some dwellings were furnished with carved sculptures that were half human, half fish. Bones found at Lepenski Vir indicated that the people there depended heavily on fish from the river. Today what remains of the village is preserved under a canopy overlooking the Danube; sculptures of goggle-eyed river gods still watch over ancient hearths. “Seventy percent of their diet was fish,” says Vladimir Nojkovic, the site’s director. “They lived here almost 2,000 years, until farmers pushed them out.”[Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

Lepenski Vir has puzzled archaeologists ever since it was excavated Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The community seemed to combine traits of local hunter-gatherer cultures of the Mesolithic period with traits of Neolithic farmers originating in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and Greece. Some discoveries made in the village, such as trapezoidal houses and fish-head figurines, were utterly unique to Lepenski Vir. Previous isotope analysis of skeletons uncovered at the site appeared to provide evidence that women from farming settlements to the south married into an established foraging community. This suggested that Lepenski Vir was a Mesolithic village whose inhabitants transitioned to an agricultural way of life. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2023

However, new research by a team including archaeologist Maxime Brami of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz raises the possibility that the village was settled by Neolithic farmers who accepted foragers and some of their practices into their community. Recent DNA analysis of 34 skeletons uncovered at the site shows that men, women, and children with genetic profiles similar to those of Neolithic farmers from Anatolia were buried beneath homes at the site, while a few people whose DNA matches that of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from Europe were buried on the periphery of the settlement. New analysis of isotope data previously gathered from the remains shows that those with Neolithic heritage ate fish along with cultivated foods, while the foragers at the site seem to have remained on a Mesolithic diet consisting mainly of fish. “What we think we see at Lepenski Vir is a settlement founded by farmers, who later adopted some foraging practices,” says Brami. “But foragers there did not become farmers.”

Europeans Shrunk When they Adopted Farming

According to Archaeology magazine: When Europeans shifted from being mobile hunter-gatherers to settled farmers, their average height declined by just over an inch, according to a new study of 167 skeletons ranging from 38,000 to 2,400 years old. The analysis, which controlled for genetic factors and examined indicators of health in the bones, supports the idea that the transition to an agricultural lifestyle had serious consequences. [Source: Zach ZORICH, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Height is a good proxy for the way nutrition and disease impact a person’s overall health, explains anthropologist Stephanie Marciniak of Penn State University. “Height really represents a snapshot of a very dynamic and very nuanced process,” she says. The researchers found that the average person still had not regained the lost inch as of about 2,400 years ago.

A second study by a research group based in Germany identified other effects of the transition to farming. This team examined the genomes of 827 ancient individuals dating to as long as 50,000 years ago, as well as genomes from 250 modern Europeans. They observed a similar drop in height resulting from the adoption of farming around 10,000 years ago, as well as an increase in risk factors for coronary artery disease. However, they found that genetic markers of greater intelligence also increased.

Early European Farmers — in Greece

According to Johannes Gutenberg Universitaet Mainz: In June 2016, an international research team led by paleogeneticists of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) published a study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showing that early farmers from across Europe have an almost unbroken trail of ancestry leading back to the Aegean. The scientists analyzed the DNA of early farmer skeletons from Greece and Turkey. According to the study, the Neolithic settlers from northern Greece and the Marmara Sea region of western Turkey reached central Europe via a Balkan route and the Iberian Peninsula via a Mediterranean route. These colonists brought sedentary life, agriculture, and domestic animals and plants to Europe. During their expansion they will have met hunter-gatherers who lived in Europe since the Ice Age, but the two groups mixed initially only to a very limited extent. "They exchanged cultural heritage and knowledge, but rarely spouses," commented anthropologist Joachim Burger, who lead the research. "Only after centuries did the number of partnerships increase." [Source: Johannes Gutenberg Universitaet Mainz, June 6, 2016 =|=]

“Professor Joachim Burger, his Mainz paleogeneticist team, and international collaborators have pioneered paleogenetic research of the Neolithization process in Europe over the last seven years. They showed a lack of interbreeding between farmers and hunter-gatherers in prehistoric Europe in 2009 and 2013 (Bramanti et al. 2009; Bollongino et al. 2013). Now, they demonstrate that the cultural and genetic differences were the result of separate geographical origins. "The migrating farmers did not only bring a completely foreign culture, but looked different and spoke a different language," stated Christina Papageorgopoulou from Democritus University of Thrace, Greece,, who initiated the study as a Humboldt Fellow in Mainz together with Joachim Burger.=|=

spread of agriculture in Europe

“The study used genomic analysis to clarify a long-standing debate about the origins of the first European farmers by showing that the ancestry of Central and Southwestern Europeans can be traced directly back to Greece and northwestern Anatolia. "There are still details to flesh out, and no doubt there will be surprises around the corner, but when it comes to the big picture on how farming spread into Europe, this debate is over," said Mark Thomas of University College London (UCL), co-author on the study. "Thanks to ancient DNA, our understanding of the Neolithic revolution has fundamentally changed over the last seven years." =|=

“Sedentary life, farming, and animal husbandry were already present 10,000 years ago in the so-called Fertile Crescent, a region covering modern-day Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq. Zuzana Hofmanová and Susanne Kreutzer, the lead authors of the study, concluded: "Whether the first farmers came ultimately from this area is not yet established, but certainly we have seen with our study that these people, together with their revolutionary Neolithic culture, colonized Europe through northern Aegean over a short period of time." =|=

“Another study has shown that the spread of farming, and farmers, was not the last major migration to Europe. Approximately 5,000 years ago people of the eastern Steppe reached Central Europe and mixed with the former hunter-gatherers and early farmers. The majority of current European populations arose as a mixture of these three groups.” =|=

In 2017, The International Business Times reports that the Archaeogenetics Research Group at the University of Huddersfield analyzed some 1,500 mitochondrial genome lineages obtained from modern DNA samples in order to study the arrival of farmers in different regions of Europe. The scientists, led by Martin Richards, found evidence suggesting that Near Eastern farmers arrived in the Mediterranean during the Late Glacial period, about 13,000 years ago. Then during the Neolithic period, about 8,000 years ago, they spread from the Mediterranean to the rest of Europe. Martin and his team hope that new sources of ancient DNA from Greece and Italy will be found for additional testing. The climate there makes it difficult to recover ancient genetic material from human remains at archaeological sites, but technological developments may could improve the odds of success. For more on early European farmers, go to “The Neolithic Toolkit.” [Source: Archaeology, April 14, 2017]

Ancient European Farmers Swiftly Spread Westward

Discoveries at two prehistoric farming villages in southern Croatia, with evidence of relatively sophisticated plant cultivation and animal herding, appears to indicate that agriculture moved westward across Europe at a fairly rapid clip. Bruce Bower wrote in Science: “Croatia does not have a reputation as a hotbed of ancient agriculture. But new excavations, described January 7 in San Antonio at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, unveil a Mediterranean Sea–hugging strip of southern Croatia as a hub for early farmers who spread their sedentary lifestyle from the Middle East into Europe. [Source: By Bruce Bower, sciencenews.org. January 7. 2011 \=]

Ancient Greek plowing

“Farming villages sprouted swiftly in this coastal region, called Dalmatia, nearly 8,000 years ago, apparently with the arrival of Middle Easterners already adept at growing crops and herding animals, says archaeologist Andrew Moore of Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. Moore codirects an international research team, with archaeologist Marko Mendušic of Croatia’s Ministry of Culture in Šibenik, that has uncovered evidence of intensive farming at Pokrovnik and Danilo Bitinj, two Neolithic settlements in Dalmatia. Plant cultivation and animal raising started almost 8,000 years ago at Pokrovnik and lasted for close to a millennium, according to radiocarbon dating of charred seeds and bones from a series of occupation layers. Comparable practices at Danilo Bitinj lasted from about 7,300 to 6,800 years ago.“Farming came to Dalmatia abruptly, spread rapidly and took hold immediately,” Moore says. \=\

“Other evidence supports a fast spread of sophisticated farming methods from the Middle East into Europe, remarks Harvard University archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef.Farming villages in western Greece date to about 9,000 years ago, he notes. Middle Eastern farmers exploited a wide array of domesticated plants and animals by 10,500 years ago, setting the stage for a westward migration, Bar-Yosef says. \=\

“Other researchers began excavating Pokrovnik and Danilo Bitinj more than 40 years ago. Only Moore and his colleagues dug deep enough to uncover signs of intensive farming. Their discoveries support the idea that agricultural newcomers to southern Europe built villages without encountering local nomadic groups, Moore asserts. Earlier excavations at Neolithic sites in Germany and France raise the possibility that hunter-gatherers clashed with incoming villagers in northern Europe, he notes. \=\

“Surprisingly, Pokrovnik and Danilo Bitinj residents grew the same plants and raised the same animals, in the same proportions, as today’s Dalmatian farmers do, Moore says. Excavated seeds and plant parts show that ancient villagers grew nine different domestic plants — including emmer, oats and lentils — and gathered blackberries and other wild fruits. Animal bones found at the two villages indicate that residents primarily herded sheep and goats, along with some cattle and a small number of pigs. Diverse food sources provided a hedge against regional fluctuations in rainfall and growing seasons, according to Moore. “This is an astonishing demonstration of agricultural continuity from the Neolithic to present times,” he says. \=\

“Aside from farming, Neolithic villagers in Dalmatia were “oriented toward the sea, and enjoyed extensive long-distance contacts,” Moore adds. Chemical analyses of obsidian chunks found at Pokrovnik and Danilo Bitinj, directed by archaeologist Robert Tykot of the University of South Florida in Tampa, trace most of them to Lipari, an island off Sicily’s north coast. Shapes and styles of pottery from the ancient Dalmatian villages changed dramatically several times during the Neolithic. Moore’s team can’t explain why these shifts occurred while the farming economy remained the same. Other than three children found in separate graves, the researchers have unearthed no human skeletons at Pokrovnik and Danilo Bitinj.” \=\

ancient Roman harvesting

Linearbandkeramik Culture and Inequality

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: About 7,500 years ago, a group of farmers known as the Linearbandkeramik (LBK) culture swept across much of Europe — and in just 500 years replaced the huntergatherer cultures that had occupied the continent in one form or another since the first humans arrived. Now, a study by an international team of scientists shows that Europe's first farmers may also have introduced social inequality to the region. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

“The researchers measured strontium isotope ratios in the bones recovered from 300 LBK burials. By matching the ratios of strontium isotopes in bones to those in the region's soils, the researchers were able to get a clear idea of where each individual had lived.

“The study showed that people who lived on the most agriculturally productive lands also tended to be buried with a ground-stone tool called an adze, which was probably used for shaping lumber and turning soil for planting. Adzes were expensive in terms of the labor needed to make them. Alexander Bentley of the University of Bristol believes that the tools indicate a slight disparity in wealth between individuals. Bentley says, "To me, this seems like the origins of inequality in something small that over the centuries was going to build up into hereditary inequality."

First British Farmers

The first farmers arrived in Britain about 6,000 years ago. Their ancestors are believed to have originated in southeast Europe. Early farmers chopped down trees so they could grow crops and vegetables. They kept cattle, sheep and pigs. These people began to settle down in one place and build permanent homes. These also built tombs and monuments on the land, of which the most enduring and famous is Stonehenge, thought to have been a gathering place for seasonal ceremonies. Other Stone Age sites include Skara Brae on Orkney, off the north coast of Scotland. It is the best preserved prehistoric village in northern Europe, helping archaeologists to understand more about how people lived near the end of the Stone Age. [Source: “Life in the United Kingdom, a Guide for New Residents,” 3rd edition, Page 15, Crown 2013]

According to the BBC: “By 3500 B.C. people in many parts of Britain had set up farms. They made clearings in the forest and built groups of houses, surrounded by fields. The early farmers grew wheat and barley, which they ground into flour. Some farmers grew beans and peas. Others grew a plant called flax, which they made into linen for clothes. [Source: BBC |::|]

“Neolithic farmers kept lots of animals. They had herds of wild cows that had been domesticated (tamed). The cattle provided beef, as well as milk and cheese. Sheep and goats provided wool, milk and meat. Wild pigs were domesticated and kept in the woods nearby. Dogs helped on the farms too. They herded sheep and cattle and worked as watchdogs. Dogs were probably treated as family pets, like they are today. The early farmers still went hunting and gathered nuts and berries to eat, but they spent most of their time working on their farms. Clearings were made to create farmland and the wood was used to build fires to keep warm at night |::|

Neolithic people built grave mounds and stone circles. They also met for religious ceremonies on large, circular platforms that are known as causewayed enclosures. People stored the bones of the dead in large graves known as long barrows. These graves were built from stone and covered with a mound of earth. They had a central passage, with several side-chambers containing sets of bones. There were also smaller graves, with a single burial chamber. During the Neolithic period, people started to build stone circles. This practice continued in the early Bronze Age. |::|

Bruce Bower wrote in sciencenews.org: “Agriculture’s British debut occurred during a mild, wet period that enabled the introduction of Mediterranean crops such as emmer wheat, barley and grapes, say archaeobotanists Chris Stevens of Wessex Archaeology in Salisbury, England, and Dorian Fuller of University College London. Farming existed at first alongside foraging for wild fruits and nuts and limited cattle raising, but the rapid onset of cool, dry conditions in Britain about 5,300 years ago spurred a move to raising cattle, sheep and pigs, Stevens and Fuller propose in the September Antiquity. With the return of a cultivation-friendly climate about 3,500 years ago, during Britain’s Bronze Age, crop growing came back strong, the scientists contend. Farming villages rapidly replaced a mobile, herding way of life. Many researchers have posited that agriculture either took hold quickly in Britain around 6,000 years ago or steadily rose to prominence by 4,000 years ago.” [Source: Bruce Bower, sciencenews.org, September 6, 2012 ~|~]

“Stevens and Fuller compiled data on more than 700 cultivated and wild food remains from 198 sites across the British Isles whose ages had been previously calculated by radiocarbon dating. A statistical analysis of these dates and associated climate and environmental trends suggested that agriculture spread rapidly starting 6,000 years ago. About 700 years later, wild foods surged in popularity and cultivated grub became rare. Several new crops — peas, beans and spelt — appeared around 3,500 years ago, when storage pits, granaries and other features of agricultural societies first appeared in Britain, Stevens and Fuller find. An influx of European farmers must have launched a Bronze Age agricultural revolution, they speculate.” ~|~

See Separate Article: FIRST BRITONS (20,000 TO 5000 YEARS AGO) europe.factsanddetails.com

ancient farming strips in Britain

8,000-Year-Old Wheat Found in Britain

An 8,000-year-old wheat grain was found at what is now a submerged cliff off the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom. The BBC reported: “Fragments of wheat DNA recovered from an ancient peat bog suggests the grain was traded or exchanged long before it was grown by the first British farmers. The research, published in Science, suggests there was a sophisticated network of cultural links across Europe. The accepted of arrival on the British mainland is around 6,000 years ago, as ancient hunter gatherers began to grow crops such as wheat and barley. [Source: Helen Briggs, BBC.com, February 27, 2015 |::|]

“The DNA of the wheat – known as einkorn – was collected from sediment that was once a peat bog next to a river. Scientists think traders arrived in Britain with the wheat, perhaps via land bridges that connected the south east coast of Britain to the European mainland, where they encountered a less advanced hunter gatherer society. The wheat may have been made into flour to supplement the diet, but a search for pollen and other clues revealed no signs that the crop was grown in Britain until much later. |::|

“Dr Robin Allaby of the University of Warwick, who led the research, said 8,000 years ago the people of mainland Britain were leading a hunter-gatherer existence, while at the same time farming was gradually spreading across Europe. “Common throughout neolithic Southern Europe, einkorn is not found elsewhere in Britain until 2,000 years after the samples found at Bouldnor Cliff,” he said. “For the einkorn to have reached this site there needs to have been contact between mesolithic [the culture between paleolithic and neolithic] Britons and neolithic farmers far across Europe. The land bridges provide a plausible facilitation of this contact. As such, far from being insular, mesolithic Britain was culturally and possibly physically connected to Europe.”|::|

“The research shows that scientists can analyse genetic material preserved within the sediments of the landscapes stretching between Britain and Europe in prehistoric times. Co-researcher Prof Vincent Gaffney, of the University of Bradford, said the find marked a new chapter in British and European history. “It now seems likely that the hunter-gather societies of Britain, far from being isolated were part of extensive social networks that traded or exchanged exotic foodstuffs across much of Europe,” he said. |::|

“And Garry Momber of the Maritime Archaeology Trust, which collected the samples from the site, said work in the Solent had opened up an understanding of the UK’s formative years in a way that he never dreamed possible. “The material remains left behind by the people that occupied Britain as it was finally becoming an island 8,000 years ago, show that these were sophisticated people with technologies thousands of years more advanced than previously recognised. The DNA evidence corroborates the archaeological evidence and demonstrates a tangible link with the continent that appears to have become severed when Britain became an island.”“|::|

First British Farms Founded by French Immigrants

In 2009, New Scientist reported: “The British may owe the French more than they care to admit. Archaeological finds from Britain show that farming was introduced 6000 years ago by immigrants from France, and that the ancient Brits might have continued as hunter-gatherers had it not been for innovations introduced by the Gallic newcomers. [Source: Newscientest.com, December 2, 2009 +++]

“Mark Collard from Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada, and his colleagues studied carbon-14 dates for ancient bones, wood and cereal grains from locations across Great Britain. From this they were able to assess how population density changed with time, indicating that around 6000 years ago the population quadrupled in just 400 years (Journal of Archaeological Science, DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2009.11.016). This coincides with the emergence of farming in Britain. +++

“Such a population explosion almost rules out the idea that farming was adopted independently by indigenous hunter-gatherers, says Collard. Pottery remains and tomb types suggest the first immigrants came from Brittany in north-west France to southern England, followed around 100 years later by a second wave from north-eastern France who settled in Scotland.” +++

Northern Europeans Slow to Adopt Farming

In 2015, New York University reported: “According to a team of researchers, northern Europeans in the Neolithic period initially rejected the practice of farming, which was otherwise spreading throughout the continent. Their findings offer a new wrinkle in the history of a major economic revolution that moved civilizations away from foraging and hunting as a means for survival. “This discovery goes beyond farming,” explains Solange Rigaud, the study’s lead author and a researcher at the Center for International Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences (CIRHUS) in New York City. “It also reveals two different cultural trajectories that took place in Europe thousands of years ago, with southern and central regions advancing in many ways and northern regions maintaining their traditions.” CIRHUS is a collaborative arrangement between France’s National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and New York University. The study, whose other authors include Francesco d’Errico, a professor at CNRS and Norway’s University of Bergen, and Marian Vanhaeren, a professor at CNRS, appears in the journal PLOS ONE. [Source: New York University, April 8, 2015]

“In order to study these developments, the researchers focused on the adoption or rejection of ornaments—certain types of beads or bracelets worn by different populations. This approach is suitable for understanding the spread of specific practices—previous scholarship has shown a link between the embrace of survival methods and the adoption of particular ornaments. However, the PLOS ONE study marks the first time researchers have used ornaments to trace the adoption of farming in this part of the world during the Early Neolithic period (8,000-5,000 B.C.).

“It has been long established that the first farmers came to Europe 8,000 years ago, beginning in Greece and marking the start of a major economic revolution on the continent: the move from foraging to farming over the next 3,000 years. However, the pathways of the spread of farming during this period are less clear. To explore this process, the researchers examined more than 200 bead-types found at more than 400 European sites over a 3,000-year period. Previous research has linked farming and foraging populations with the creation and adornment of discrete types of beads, bracelets, and pendants. In the PLOS ONE study, the researchers traced the adoption of ornaments linked to farming populations in order to elucidate the patterns of transition from foraging and hunting to farming.

“Their results show the spread of ornaments linked to farmers—human-shaped beads and bracelets composed of perforated shells—stretching from eastern Greece and the Black Sea shore to France’s Brittany region and from the Mediterranean Sea northward to Spain. By contrast, the researchers did not find these types of ornaments in the Baltic region of northern Europe. Rather, this area held on to decorative wear typically used by hunting and foraging populations—perforated shells rather than beads or bracelets found in farming communities. “It’s clear hunters and foragers in the Baltic area resisted the adoption of ornaments worn by farmers during this period,” explains Rigaud. “We’ve therefore concluded that this cultural boundary reflected a block in the advancement of farming—at least during the Neolithic period.”“

6,000-Year-Old Baltic Cooking Pots Show Gradual Transition to Agriculture

Ceramic pots excavated at sites dated to 4,000 years B.C. tell a story of some lingering hunter-gatherer ways in the Baltic regions of Northwest Europe. AZERTAC reported: “Once a fisherman, always a fisherman, one might say. This could have been the sentiment of the people who lived 6,000 years ago in what is today the Western Baltic regions of Northern Europe. Based on a study recently performed by a team of researchers led by Oliver Craig of the University of York and Carl Heron of the University of Bradford, hunter-gatherer humans here may have experienced a gradual rather than a rapid transition to agriculture. [Source:AZERTAC, October 27, 2011 ~\~]

“The researchers analyzed cooking residues preserved in 133 ceramic vessels from the Western Baltic regions of Northern Europe to determine if the residues originated from terrestrial food sources, or marine and freshwater organisms. The vessels were chosen from 15 sites dated to approximately 4,000 B.C., the time corresponding to the first evidence in the region indicating domestication of animals and plants (agriculture and animal husbandry). The evidence included samples obtained from a 6,000-year-old submerged settlement site excavated by the Archäologisches Landesmuseum in Schleswig off the Baltic coast of Northern Germany. Of the inland sites, about 28 percent of the pots showed residues from aquatic organisms, likely freshwater fish. Of the sites located in coastal areas, one-fifth of the pots showed biochemical traces of aquatic organisms, along with fats and oils normally not present in terrestrial plants and animals. ~\~

“The study results suggest that fish and other aquatic resources continued to be significantly exploited even after the advent of farming and domestication. Says Craig: "This research provides clear evidence people across the Western Baltic continued to exploit marine and freshwater resources despite the arrival of domesticated animals and plants. Although farming was introduced rapidly across this region, it may not have caused such a dramatic shift from hunter-gatherer life as we previously thought." ~\~

“The study will also provide a model and foundation for use by future scientists and researchers in the area of ancient pottery analysis. "Our data set represents the first large scale study combining a wide range of molecular evidence and single-compound isotope data to discriminate terrestrial, marine and freshwater resources processed in archaeological ceramics and it provides a template for future investigations into how people used pots in the past," says Carl Heron, team co-leader and Professor of Archaeological Sciences at the University of Bradford. ~\~

“The research effort consisted of an international team of archaeologists from the University of York, the University of Bradford, the Heritage Agency of Denmark, the National Museum of Denmark, Moesgård Museum (Denmark), Christian-Albrechts-Universität, Kiel (Germany) and the Archäologisches Landesmuseum, Schleswig (Germany). It was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and the details, results and conclusions are now published online in the most recent edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).” ~|~

Baltic Hunter-Gatherers Adopted Farming, Rather Than Being Pushed Out by Migrants

ancient hoes from Germany and Spain

The Neolithic peoples of the Baltics acquired agriculture and other elements of permanent settlement culture through diffusion, not through large migratory movements from Anatolia and the Middle East, according to genetic study. Trinity College Dublin reported: “Research indicates that Baltic hunter-gatherers were not swamped by migrations of early agriculturalists from the Middle East, as was the case for the rest of central and western Europe. Instead, these people probably acquired knowledge of farming and ceramics by sharing cultures and ideas—rather than genes—with outside communities. Scientists extracted ancient DNA from a number of archaeological remains discovered in Latvia and the Ukraine, which were between 5,000 and 8,000 years old. These samples spanned the Neolithic period, which was the dawn of agriculture in Europe, when people moved from a mobile hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a settled way of life based on food production. [Source: Trinity College Dublin, March 2, 2017 ^*^]

“We know through previous research that large numbers of early farmers from the Levant (the Near East) – driven by the success of their technological innovations such as crops and pottery – had expanded to the peripheral parts of Europe by the end of the Neolithic and largely replaced hunter-gatherer populations. However, the new study, published today in the journal Current Biology, shows that the Levantine farmers did not contribute to hunter-gatherers in the Baltic as they did in Central and Western Europe. ^*^

“The research team, which includes scientists from Trinity College Dublin, the University of Cambridge, and University College Dublin, says their findings instead suggest that the Baltic hunter-gatherers learned these skills through communication and cultural exchange with outsiders. The findings feed into debates around the ‘Neolithic package,’—the cluster of technologies such as domesticated livestock, cultivated cereals and ceramics, which revolutionised human existence across Europe during the late Stone Age. ^*^

“Advances in ancient DNA work have revealed that this ‘package’ was spread through Central and Western Europe by migration and interbreeding: the Levant and later Anatolian farmers mixing with and essentially replacing the hunter-gatherers. But the new work suggests migration was not a ‘universal driver’ across Europe for this way of life. In the Baltic region, archaeology shows that the technologies of the ‘package’ did develop—albeit less rapidly—even though the analyses show that the genetics of these populations remained the same as those of the hunter-gatherers throughout the Neolithic. ^*^

“Andrea Manica, one of the study’s senior authors from the University of Cambridge, said: “Almost all ancient DNA research up to now has suggested that technologies such as agriculture spread through people migrating and settling in new areas. However, in the Baltic, we find a very different picture, as there are no genetic traces of the farmers from the Levant and Anatolia who transmitted agriculture across the rest of Europe. The findings suggest that indigenous hunter-gatherers adopted Neolithic ways of life through trade and contact, rather than being settled by external communities. Migrations are not the only model for technology acquisition in European prehistory.” ^*^

“While the sequenced genomes showed no trace of the Levant farmer influence, one of the Latvian samples did reveal genetic influence from a different external source—one that the scientists say could be a migration from the Pontic Steppe in the east. The timing (5-7,000 years ago) fits with previous research estimating the earliest Slavic languages. Researcher Eppie Jones, from Trinity College Dublin and the University of Cambridge, was the lead author of the study. She said: “There are two major theories on the spread of Indo-European languages, the most widely spoken language family in the world. One is that they came from the Anatolia with the agriculturalists; another that they developed in the Steppes and spread at the start of the Bronze Age.That we see no farmer-related genetic input, yet we do find this Steppe-related component, suggests that at least the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family originated in the Steppe grasslands of the East, which would bring later migrations of Bronze Age horse riders.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024