Home | Category: First Modern Human Art and Culture

CHAUVET CAVE

On Christmas Eve, 1994, three spelunkers — Jean-Marie Chauvet and his friends Elitte Brune and Christian Hillaire — made one of the greatest archaeological discoveries ever inside a cave near Pont-d'Arc in the Ardéche region of southern France, an area popular with cavers. The cave is officially named Chauvet-Pont d’Arc. [Source: Jean Clottes, National Geographic, August 2001]

On Christmas Eve, 1994, three spelunkers — Jean-Marie Chauvet and his friends Elitte Brune and Christian Hillaire — made one of the greatest archaeological discoveries ever inside a cave near Pont-d'Arc in the Ardéche region of southern France, an area popular with cavers. The cave is officially named Chauvet-Pont d’Arc. [Source: Jean Clottes, National Geographic, August 2001]

What the spelunkers found was Chauvet Cave, named after one of its discoverers."Tears were running down my cheeks," Jean Clottes, France foremost expert on cave art, said of his first glimpse of the paintings. "I was witnessing one of the world's greatest masterpieces...I was so overcome...It was like going into an attic and finding a da Vinci. except that the great master was unknown."

Chauvet Cave is regarded as more impressive and beautiful than Lascaux cave by people who have seen both. Chauvet contains stone engravings and paintings with 420 animal figures. Some paintings are 35,000 years old paintings, some of the oldest cave paintings known to science. The images are almost twice as old and more than twice as large as the images in Lascaux and Altamira.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CHAUVET CAVE: PAINTINGS, IMAGES, SPIRITUALITY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S EARLIEST ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CAVE ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WHY EARLY HUMANS MADE ART factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

IMAGES IN EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART: ANIMALS, HAND PRINTS, FIGURES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL ART, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEARS OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

CAVE ART IN SPAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAVE ART IN FRANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LASCAUX CAVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST SCULPTURES factsanddetails.com ;

VENUS STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times” by Jean Clottes (2003) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave” by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs” by Mario Ruspoli (1987) Amazon.com;

“Stepping-Stones: A Journey through the Ice Age Caves of the Dordogne” by Christine Desdemaines-Hugon (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Altamira” by Matilde Muzquiz Perez-Seoane, Frederico Bernaldo de Quiros (1999) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008) Amazon.com;

“What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity” by Jean Clottes Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist Amazon.com;

“The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art” by Paul Bahn (2017) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art (World of Art)” (2017) by Bruno David Amazon.com;

“Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe” by Paul Bahn Amazon.com;

“Images of the Ice Age” by Paul G. Bahn Amazon.com;

“The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art” by David Lewis-Williams (2004) Amazon.com;

Discovery of Chauvet Cave

Chauvet Cave location

Jean-Marie Chauvet was a park ranger working the Ministry of Culture and a custodian of the prehistoric sites in the region when the cave was found. He and his friends, Brune and Hillaire, were looking for prehistoric caves. The entrance to the one they found had been covered for millennia by a landside.

A few days before discovering the cave they "felt a draft coming out of the ground...For us that is sign there is something else." After digging out the hole they found the two men and one women squeezed through a narrow tunnel and lowered themselves 30 feet down on a rope where they found a spectacular gallery of prehistoric old paintings. "I thought I was dreaming," said one of the spelunkers, "We were all covered with goose pimples...It was a great moment. We all shouted and yelled." The spelunkers were aware of the damage they might cause. The next time they entered the cave they laid down a roll of plastic so they wouldn't disturb the archaeological integrity of the site. Chauvet had the cave named after him. Brune and Hillaire were honored with their names attached to chambers.

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: On a “cold afternoon in December 1994....three friends and weekend cavers—Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel and Christian Hillaire—followed an air current into an aperture in a limestone cliff, tunneled their way through a narrow passage, using hammers and awls to chip away at the rocks and stalactites that blocked their progress, and descended into a world frozen in time—its main entrance blocked off by a massive rock slide 29,000 years ago. Brunel, the first to wedge through the passage, glimpsed surreal crystalline deposits that had built up for millennia, then stopped before a pair of blurry red lines drawn on the wall to her right. “They have been here,” she shouted to her awe-struck companions. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

“The trio moved gingerly across the earthen floor, trying not to tread on the crystallized ashes from an ancient fire pit, gazing in wonder at hundreds of images. “We found ourselves in front of a rock wall covered entirely with red ocher drawings,” the cavers remembered in their brief memoir published last year. “The panel contained a mammoth with a long trunk, then a lion with red dots spattered around its snout in an arc, like drops of blood. We crouched on our heels, gazing at the cave wall, mute with stupefaction.”“ ||/

Disputes Involved with the Discovery of Chauvet Cave

Chauvet cave bear "shrine"

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: But story begins in the spring of 1994, “when a veteran spelunker and friend of Jean-Marie Chauvet, Michel Rosa, known to friends as Baba, initially detected air seeping from a small chamber blocked by stones. According to close friends of both men, it was Baba who suggested the airflow was coming from a cave hidden behind the rocks. Baba, they said, tried to climb into the hole, only to give up after reaching a stalactite he couldn’t move by hand. The aperture became known among spelunkers as Le Trou de Baba, or Baba’s Hole. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

“Chauvet has maintained that Rosa—a reclusive figure who has rarely spoken publicly about the case—lost interest in the site and moved on to explore other caves. Others insist that Baba had always planned to come back—and that Chauvet had cheated him out of the chance by returning, unannounced, with Eliette Brunel six months later. Chauvet violated a caver’s code of honor, says Michel Chabaud, formerly one of his closest friends. “On the level of morality,” he says, “Chauvet did not behave well.” Baba vanished into obscurity and Chauvet’s name was attached to one of the world’s greatest cultural treasures. ||/

“It was just a few dozen yards from this spot that another drama played out on the night of December 24, 1994—a story that has re-emerged in the public eye and renewed old grievances. At Chauvet’s invitation, Michel Chabaud and two other spelunkers, all close friends and occasional visitors to the Trou de Baba, entered the cave to share with the original three their exhilaration at the discovery. Six days after their find, Chauvet, Brunel and Hillaire had not yet explored every chamber. Chabaud and his two friends pushed into the darkness—and became the first humans in 30,000 years to penetrate the Gallery of the Lions, the End Chamber, where the finest drawings were found. “We saw paintings everywhere, and we went deeper and deeper,” Chabaud wrote in his diary that evening. “We were in a state of incredible excitement Everyone was saying, ‘incredible, this is the new Lascaux.’” Chabaud and his companions showed the chamber they discovered to Chauvet, he says, and asked for recognition of their role in the find. Chauvet brushed them off, saying dismissively, “You were only our guests.” ||/

Chauvet Cave After Its Discovery

The French government spent two years and $2 million widening the entrance, installing video surveillance cameras and preparing a staging area for human visitors. Since then guards have been posted at the entrance around the clock. The entrance itself resembles a bank vault with a metal door and double key system. Voice alarms go off if anyone approached too closely. Inside the cave a metal catwalk was installed in one section.

For years exploration of the cave was blocked by lawsuits over who owned the cave. Scientists didn't visit it again until 1999, when they photographed the images using 35-mm, infrared, and digital cameras and scanned the images into computers that brightened the colors and intensified the contrast.

The lawsuits pitted the French government against Jean-Marie Chauvet and his partners as well as the owners of the land on which the cave stands, The suit was settled with the finders entitled to royalties from reproductions of the art inside the cave and the owners of the land entitled to “treasure” found on the land, which technically means they have the same right landowners have when gold or oil is found on their land.

The plan was for cave to be bought from its landowner and sealed off to everyone except for scientists. "Our goal," said Béghain, " is to keep the cave in this virgin state so that research theoretically continue indefinitely." A replica of Chauvet is being built nearby by local authorities in Ardeche. Only a few select group of scholars and journalists are allowed in the cave. They are only allowed in the cave for brief periods in the spring and autumn and it is not unusual for the cave trips to be cancelled because of some problem or another.

Impact of Chauvet Cave

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Within months, Chauvet, would revolutionize our understanding of emerging human creativity. Radiocarbon dating conducted on 80 charcoal samples from the paintings determined that the majority of the works dated back 36,000 years—more than double the age of any comparable cave art yet uncovered. A second wave of Paleolithic artists, scientists would determine, entered the cave 5,000 years later and added dozens more paintings to the walls. Researchers were compelled to radically revise their estimates of the period when Homo sapiens first developed symbolic art and began to unleash the power of imagination. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

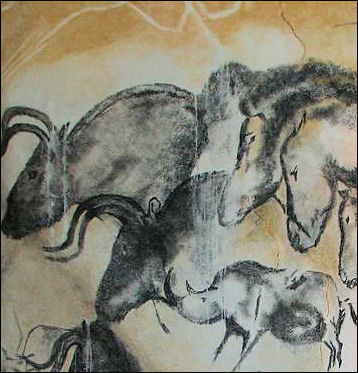

“At the height of the Aurignacian period—between 40,000 and 28,000 years ago—when Homo sapiens shared the turf with the still-dominant Neanderthals, this artistic impulse may have signaled an evolutionary leap. While Homo sapiens were experimenting with perspective and creating proto-animation on the walls, their cousins, the Neanderthals, shuffling toward extinction, had not moved beyond the production of crude rings and awls. The finding also demonstrated that Paleolithic artists had painted in a consistent style, using similar techniques for 25,000 years—a remarkable stability that is the sign, Gregory Curtis wrote in The Cave Painters, his major survey of prehistoric art, of “a classical civilization.” ||/

Jean Clottes: the Man Closest to Chauvet Cave

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “A few days after Christmas in 1994, Jean Clottes, a pre-eminent scholar of rock art and then an archaeology official in the French Ministry of Culture, received a call from a conservator, asking Clottes to rush to the Ardèche Gorge to verify a find. “I had my family coming; I asked whether I could do it after the New Year,” Clottes recalls one day at his home in Foix, in the Pyrenees south of Toulouse. “He said, ‘No, you’ve got to come right away. It looks like a big discovery. They say there are hundreds of images, lots of lions and rhinos.’ I thought that is bizarre, because representations of lions and rhinos are not very frequent in caves.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

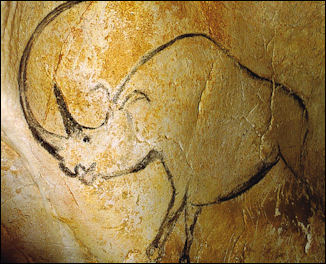

“Clottes arrived at the grotto and inched with great difficulty through the air shaft: “It was not horizontal. It sloped down, and then it turned, and then it sloped up. ” As he approached the walls in the darkness, peering at the images through his headlamp, Clottes could sense immediately that the works were genuine. He stared, enthralled, at the hand-size red dots that covered one wall, a phenomenon he had never observed before. “Later we found out that they were done by putting wet paint inside the hand, and applying the hand against the wall,” he says. “At the time, we didn’t know how they were made.” Clottes marveled at the verisimilitude of the wild horses, the vitality of the head-butting woolly rhinos, the masterful use of the limestone walls. “These were hidden masterpieces that nobody had laid eyes on for thousands and thousands of years, and I was the first specialist to see them,” he says. “I had tears in my eyes.” ||/

“Clottes’ original interpretation of Paleolithic art was at once embraced and ridiculed by fellow scholars. One dismissed it as “psychedelic ravings.” Another titled his review of the Clottes-Lewis-Williams book, “Membrane and Numb Brain: A Close Look at a Recent Claim for Shamanism in Paleolithic Art.” One colleague berated him for “encouraging the use of drugs” by writing lyrically about the trancelike states of the Paleo shamans. “We were accused of all sorts of things, even of immorality,” Clottes tells me. “But altered states of consciousness are a fundamental part of us. It is a fact.” ||/

“Clottes found a champion in the German director Werner Herzog, who made him the star of his documentary about Chauvet, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and popularized Clottes’ theories. “Will we ever be able to understand the vision of these artists across such an abyss of time?” Herzog asks, and Clottes, on camera, provides an answer. For the artists, “There [were] no barriers between the world where we are and the world of the spirits. A wall can talk to us, can accept us or refuse us,” he said. “A shaman can send his or her spirit to the world of the supernatural or can receive the visit inside him of supernatural spirits...you realize how different life must have been for those people from the way we live now.” ||/

“In the years since his theory of a prehistoric vision quest first stirred debate, Clottes has been challenged on other fronts. Archaeologists have insisted that the samples used to date the Chauvet paintings must have been contaminated, because no other artworks from that period have approached that level of sophistication. Declaring the paintings to be 32,000 years old was like claiming to have found “a Renaissance painting in a Roman villa,” scoffed British archaeologist Paul Pettit, who insisted they were at least 10,000 years younger. The findings “polarized the archaeological world,” said Andrew Lawson, another British archaeologist.

Study of Chauvet Cave

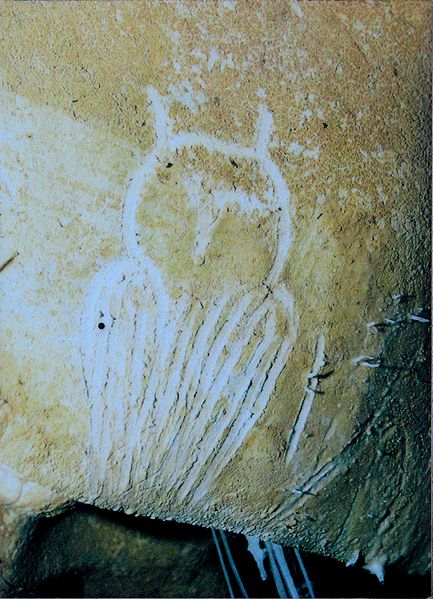

owl made from cave bear

claw marks Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Paleontologists (who study animal remains inside the cave, mainly of bears but also wolves, ibexes and other mammals), geologists (who examine how the cave evolved and what this can tell us about prehistoric people’s actions inside it), art historians (who study the painted and engraved walls in all their detail) and other specialists visit Chauvet on a regular basis, adding to our understanding of the site. They have mapped every square inch with advanced 3-D technology, counted the bones of 190 cave bears and inventoried the 425 animal images, identifying nine species of carnivores and five species of ungulates. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

“ They have documented the pigments used—including charcoal and unhydrated hematite, a natural earth pigment otherwise known as red ocher. They have uncovered and identified the tools the cave artists employed, including brushes made from horse hair, swabs, flint points and lumps of iron oxides dug out of the ground that could be molded into a kind of hand-held, Paleolithic crayon. They have used geological analysis and a laser-based remote sensing technology to visualize the collapse of limestone slabs that sealed access to Chauvet Cave until its 1994 rediscovery. ||/

“One recent study, co-directed by Clottes, analyzed the faint traces left by human fingers on a decorated panel in the End Chamber. The fingers were pressed against the wall and moved vertically or horizontally against the soft limestone before the painter drew images of a lion, rhinoceros, bison and bear. Clottes and his co-researcher, Marc Azéma, theorize that the tracing was a shamanistic ritual intended to establish a link between the artist and the supernatural powers inside the rock. Prehistorian Norbert Aujoulat studied a single painting, Panel of the Panther, identified the tools used to create the masterwork and found other images throughout the cave that were produced employing the same techniques. Archaeologists Dominique Baffier and Valérie Feruglio have focused their research on the large red dots on the Chauvet walls, and determined that they were made by two individuals—a male who stood about 5-foot-9 and a female or adolescent—who coated their hands with red ocher and pressed their palms against the limestone. ||/

“Jean-Michel Geneste, Clottes’ successor as scientific director of Chauvet, leads two 40-person teams of experts into the grotto each year—in March and October—for 60 hours of research over 12 days. Geneste co-authored a 2014 study that analyzed a mysterious assemblage of limestone blocks and stalagmites in a side alcove. His team concluded that Paleolithic men had arranged some of the blocks, perhaps in the process of opening a conduit to paintings in other chambers, perhaps for deeper symbolic reasons. Geneste has also paid special attention to depictions of lions, symbols of power accorded a higher status than other mammals. “Some of the lion paintings are very anthropomorphic,” he observes, “with a nose and human profile showing an empathy between the artists and these carnivores. They are painted completely differently from other animals in Chauvet.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

Werner Herzog's Film About Chauvet Cave

In March 2010, Archaeology magazine reported, preeminent German filmmaker Werner Herzog was given unprecedented access to Chauvet Cave in southeastern France to film the site's Paleolithic art. The result, his film Cave of Forgotten Dreams , which was released in spring 2011, is a document of some of humankind's earliest and most extraordinary paintings. Since the cave was discovered in December 1994, few people, mostly researchers, have seen the artwork, owing to the cave's extremely delicate climate and concerns about preserving the ancient paintings. But the film is more than a tour of the cave. It is an exploration of what the science of archaeology is revealing about the Aurignacian people — Europe's first artists — and the origins of the modern human mind. Part of the film focuses on the work of Jean Clottes, the former director of research for the Chauvet Cave Project, and Jean-Michel Geneste, the project's current director, and what their work tells us about how the Aurignacian people may have lived their lives and connected to their world through art. Herzog's experience as a hunter and a long-distance walker helped him understand certain aspects of their lives.[Source: Archaeology magazine, March/April 2011]

On why Chauvet is so exceptional Herzog told Archaeology magazine: “It is one of the greatest and most sensational discoveries in human culture and, of course, what is so fascinating is that it was preserved as a perfect time capsule for 20,000 years. The quality of the art, which is from a time so far, so deep back in history, is stunning. It's not that we have what people might call the primitive beginnings of painting and art. It is right there as if it had burst on the scene fully accomplished. That is the astonishing thing, to understand that the modern human soul somehow awakened. It is not a long slumber and a slow, slow, slow awakening. I think it was a fairly sudden awakening. But when I say "sudden" it may have gone over 20,000 years or so. Time does not factor in when you go back into such deep prehistory.

On the difficulties shooting a 3-D film in a cave, Herzog said, “Of course, we were only allowed to take along what we could carry in our own hands, so we couldn't move heavier equipment into the cave. The most intense challenge came from the fact that when filming in 3-D, you cannot move a 3-D camera around like a regular film camera. If you move, for example, closer to an object, the lenses actually have to be closer together, and when you are fairly close you even have to make them "squint" slightly. We had to reconfigure our camera to take close-up shots of the paintings. It is a high-precision, technical thing to have to do, in semidarkness on a narrow walkway. We had a fairly brief period of time to film. When the researchers left in early April, I had the cave practically undisturbed for filming, but only for six days, and only four hours each day. Of course, later in the season the carbon dioxide level in the branch of the cave where you have the Panel of the Lions becomes dangerously high. In other parts of the cave there is a fairly high level of radon, and it has a cumulative effect on your lungs. So, we had to move around between toxic gases and radioactive gases.

When asked why he choose to film in 3-D, Herzog said: “3-D was imperative because I initially thought there were flat walls and paintings in the cave. But there are no flat areas. The drama of the bulges and niches was actually used by the artists. They did it with phenomenal skill, with great artistic skill, and there was something expressive about it, a drama of rock transformed and utilized, in the drama of paintings. This is why it was imperative to shoot in 3-D.

Government Control of Chauvet Cave

Chauvet cave lions Since 1994 Chauvet Cave has been rigidly and forcefully protected by the French Ministry of Culture. Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Immediately upon Chauvet’s discovery—even before it was announced—French authorities installed a steel door at the entrance and imposed stringent access restrictions. In 2014, a total of 280 individuals—including scientists, specialists working on the simulation and conservators monitoring the cave—were allowed to enter, typically spending two hours in a single visit.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

According to UNESCO: “The decorated cave of Pont d’Arc, known as Grotte Chauvet-Pont d’Arc is protected at the highest national level as a historic monument. Likewise, the buffer zone benefits from the highest level of national protection since early 2013. The buffer zone accordingly will not permit future development. [Source: UNESCO =]

“The focus of management is the implementation of a preventive conservation strategy based on constant monitoring and non-intervention. Several monitoring systems have been installed in the cave which form an integral part of these preventive conservation efforts. Any changes in relative humidity and/or the air composition inside the cave may have severe effects on the condition of the drawings and paintings. It is due to this risk that the cave will not be open to the general public, but also that future visits of experts, researchers and conservators will need to be restricted to the absolute minimum necessary. Despite the delicateness of paintings and drawings, no conservation activities have been carried out in the cave and it is intended to retain all paintings and drawings in the fragile but pristine condition in which they were discovered. =

“The management authorities have implemented a management plan (2012-16), based on strategic objectives, activity fields and concrete actions, which are planned with time frames, institutional responsibilities, budget requirements and quality assurance indicators. The latter will allow for full quality assurance after the cycle of implementation in 2016, following which the management plan will have to be revised for future management processes. =

“After it became clear that the cave would never be accessible to the general public, the idea of a facsimile reconstruction to provide interpretation and presentation facilities emerged. The Grand Projet Espace de Restitution de la Grotte Chauvet (ERGC) was established, with the aim of creating a facsimile reconstruction of the cave with its paintings and drawings, and a discovery and interpretation area to attract visitors. =

Chauvet Cave Site

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Paulo Rodrigues and Charles Chauveau, conservators overseeing the site, are climbing a path beyond a vineyard through a forest of pine and chestnut toward the base of a limestone cliff perforated with grottoes. It’s a cold, misty morning in December, and wisps of fog drift over the neat rows of vines and the Ardèche River far below. The Pont d’Arc, the limestone arch that spans the river, lies obscured behind the trees. During the Aurignacian period, Rodrigues tells me, the vegetation was much sparser here, and the Pont d’Arc would have been visible from the rock ledge that we’re now walking on; from this angle the formation bears a striking resemblance to a mammoth. Many experts believe that early artists deliberately selected the Chauvet cave for their vision quests because of its proximity to the limestone monolith. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

“After following the path along the cliff, the conservators and I stop before a grotto used to store equipment and monitor the atmosphere inside Chauvet. “We are doing all we can to limit the human presence, so as not to alter this equilibrium,” says Chauveau, showing me a console with removable air-sample tubes that measure the level of radon, a colorless, odorless radioactive gas released from decaying uranium-ore deposits inside caves. “The goal is to keep the cave in the exact condition that it was found in 1994,” he adds. “We don’t want another Lascaux on our hands.” The two conservators make their way here weekly, checking for intruders, making certain that air filters and other equipment are running smoothly. ||/

“Afterward, we follow a wooden walkway, constructed in 1999, that leads to the Chauvet entrance. Rodrigues points to a massive slab of limestone, covered in moss, orange mineral deposits and weeds—“all of that rock slid down, and covered the original entrance.” At last we arrive at a set of wooden steps and climb to the four-foot-high steel door that seals off the aperture. It is as far as I am permitted to go: The Culture Ministry bars anyone from entering the cave during the damp and cold Provençal winter, when carbon dioxide levels inside the grotto reach 4 percent of the total atmosphere, twice as high as the amount considered to be safe to breathe.” ||/

Chauvet Teverga

Chauvet Cave Museum Experience

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “As I descend a footpath through subterranean gloom, limestone walls tower 40 feet and plunge into a chasm. Gleaming stalactites dangle from the ceiling. After several twists and turns, I reach a cul-de-sac. As I shine my iPhone flashlight on the walls, out of the darkness emerge drawings in charcoal and red ocher of woolly rhinos, mammoths and other mammals that began to die out during the Pleistocene era, about 10,000 years ago. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

“It feels, and even smells, like a journey into a deep hole in the earth. But this excursion is actually taking place in a giant concrete shed set in the pine-forested hills of the Ardèche Gorge in southern France. The rock walls are stone-colored mortar molded over metal scaffolding; the stalactites were fashioned from plastic and paint in a Paris atelier. Some of the wall paintings are the work of my guide, Alain Dalis, and the team of fellow artists at his studio, Arc et Os, in Montignac, north of Toulouse. Dalis pauses before a panel depicting a pride of lions in profile, sketched with charcoal. “These were drawn on polystyrene, a synthetic resin, then fitted to the wall,” he tells me. The result is a precise, transfixing replica of the End Chamber, also called the Gallery of Lions, inside the actual Chauvet Cave, located three miles from here and widely viewed as the world’s greatest repository of Upper Paleolithic art. ||/

“The $62.5 million facsimile is called the Caverne du Pont d’Arc, after a nearby landmark—a natural archway of eroded limestone spanning the Ardèche River and known to humans since Paleolithic times. The replica, opening to the public this month, has been in the works since 2007, when the Ardèche departmental government, recognizing that an international audience was clamoring to view the cave, decided to join with other public and private funders to build a simulacrum. Restrictions imposed by the French Ministry of Culture bar all but scientists and other researchers from the fragile environment of the cave itself. ||/

“Five hundred people—including artists and engineers, architects and special-effects designers—collaborated on the project, using 3-D computer mapping, high-resolution scans and photographs to recreate the textures and colors of the cave. “This is the biggest project of its kind in the world,” declares Pascal Terrasse, the president of the Caverne du Pont d’Arc project and a deputy to the National Assembly from Ardèche. “We made this ambitious choice... so that everybody can admire these exceptional, but forever inaccessible treasures.” ||/

“When I arrived at the Caverne du Pont d’Arc for a preview that rainy morning this past December, I was skeptical. The installation’s concrete enclosure was something of an eyesore in an otherwise pristine landscape—like a football stadium plunked down at Walden Pond. I feared that a facsimile would reduce the miracle of Chauvet to a Disneyland or Madame Tussaud-style theme park—a tawdry, commercialized experience. But my hopes began to rise as we followed a winding pathway flanked by pines, offering vistas of forested hills at every turn. At the entrance to the recreated cave, a dark passage, the air was moist and cool—the temperature maintained at 53.5 degrees, just as in Chauvet. The rough, sloping rock faces, streaked with orange mineral deposits, and multi-spired stalactites hanging from the ceiling, felt startlingly authentic, as did the reproduced bear skulls, femurs and teeth littering the earthen floors. The paintings were copied using the austere palette of Paoleolithic artists, traced on surfaces that reproduced, bump for bump, groove for groove, the limestone canvas used by ancient painters. ||/

“The exactitude owed much to the participation of some of the most preeminent prehistoric cave experts in France, including Clottes and Geneste. The team painstakingly mapped every square inch of the real Chauvet by using 3-D models, then shrinking the projected surface area from 8,000 to 3,000 square meters. Architects suspended a frame of welded metal rods—shaped to digital coordinates provided by the 3-D model—from the roof of the concrete shell. They layered mortar over the metal cage to re-create the limestone inside Chauvet. Artists then applied pigments with brushes, mimicking the earth tones of the cave walls, based on studies conducted by geomorphologists at the University of Savoie in Chambery. Artists working in plastics created crystal formations and animal bones. Twenty-seven panels were painted on synthetic resin in studios in both Montignac, in the Dordogne; and in Toulouse. “We wanted the experience to resemble as closely as possible the feeling of entering the grotto,” artist Alain Dalis told me.” ||/

Discoverers of Chauvet Cave Squabble Over the Profits

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “I caught up with the three original discoverers—or inventeurs, as the French often call them...The national press had picked up on the revived quarrel over the cave’s discovery. A headline in the French edition of Vanity Fair declared, “The Chauvet Cave and Its Broken Dreams.” New allegations were being aired, including a charge that one of the three discoverers, Christian Hillaire, had not even been at the cave that day. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

“The fracas was playing out against protracted haggling between the trio and the Caverne du Pont d’Arc’s financial backers. At stake was the division of profits from the sale of tickets and merchandise, a deal said to be worth millions. Chauvet and his companions had received $168,000 apiece from the French government as a reward for their discovery, and some officials felt the three did not deserve anything more. “They are just being greedy,” one official told me. (The Lascaux discoverers had never received a penny.) With negotiations stalled, the project’s backers had stripped the name “Chauvet” from the Caverne du Pont d’Arc facsimile—it was supposed to have been called the Caverne Chauvet-Pont d’Arc—and withdrawn invitations for the three to the opening. The dispute was playing into the hands of the inventeurs’ opponents. Pascal Terrasse of the Pont d’Arc project announced he was suspending talks with the trio because, he told Le Point newspaper, “I can’t negotiate with the people who aren’t the real discoverers.” ||/

“Christian Hillaire, stocky and rumpled, told me after weeks of what he deemed lies drummed up by a “cabal organized against us,” they could no longer remain silent. “We have always avoided making claims, even when we’re attacked,” said Eliette Brunel, a bespectacled, elegant and fit-looking woman, as we strolled down an alley in St. Remèze, her hometown, which was dead quiet in the wintry off-season. “But now, morally, we cannot accept what is happening.” Chauvet, a compact man with a shock of gray hair, said that the falling out with his former best friends still pained him, but he had no regrets for the way he had acted. “The visit [to the Chauvet Cave] on December 24th was a great convivial moment,” he said. “Everything that happened afterward was a pity. But we were there first, on the 18th of December. That can’t be forgotten. It’s sad that [our former friends] can no longer share this satisfying moment with us, but that was their choice.” ||/

“We walked together back to the Town Hall...Chauvet addressed the gathering in the courtyard. He referred mockingly to the fact that he hadn’t been invited to the opening of the facsimile (“I’ll have to pay €8 like everyone else”) but insisted that he wasn’t going to be dragged into the controversy. “The important thing is that what we discovered inside that cave belongs to all of humanity, to our children,” he said, to applause, “and as for the rest of it, come what may.” ||/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024