Home | Category: Neanderthal Art and Culture / First Modern Human Art and Culture

CAVE ART IN SPAIN

Altamira bison Miranda S. Spivack wrote in the Washington Post: “For aficionados of early human art like my husband and me, Spain may be the best destination in Europe (some say the world) to see all kinds of prehistoric art, up close. Spain’s sites, scattered throughout the country, include dozens of dimly lit caves like this one as well as hundreds of “abrigos,” or outdoor overhangs, where the images are still very bright. “If you are interested in the very origins of artistic expression, this is where you need to be,” said Ian Tattersall, a specialist in Spanish cave art and a former curator at New York’s American Museum of Natural History. “What is really cool about many of the Spanish caves is the fact that they cover a period of cave art not very common in France,” although that is where their name comes from. That would be the Solutrean period of more than 20,000 years ago, Tattersall said. [Source: Miranda S. Spivack, Washington Post, October 30, 2014 ^||^]

Most of Spain’s cave art — including the famous cave paintings of Altamira — is in northern Spain. Some of the oldest cave art in the world is thought to be in El Castillo, a popular Spanish cave an hour’s drive away near the town of Puente Viesgo, where there are outlines of human hands as well as images of animals. The cave artists only occasionally drew human forms. Those are often simpler than the animal portraits: stick figures, mysterious symbols that may denote fertility. Or not. “There is always an explanation du jour, and everybody has their own pet theory about this stuff,” Tattersall said. “It does beg to be explained, but we only know that these deep cave sites that are decorated were very special and meaningful places to the people who made them.”^||^

“Sometimes the artists were remarkably sophisticated, such as in Covalanas, in the Cantabrian region, where the artist was able to incorporate the curve of the stone to make it seem that the animals were running. These works combine sculpture and painting, alongside hand prints and dots.” ^||^

Websites and Resources on Prehistoric Art: Chauvet Cave Paintings archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet ; Cave of Lascaux archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en; Trust for African Rock Art (TARA) africanrockart.org; Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com; Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology, by Peter Brown peterbrown-palaeoanthropology.net; Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RELATED ARTICLES:

WORLD'S EARLIEST ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CAVE ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WHY EARLY HUMANS MADE ART factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

IMAGES IN EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART: ANIMALS, HAND PRINTS, FIGURES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL ART, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEARS OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

CAVE ART IN FRANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LASCAUX CAVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CHAUVET CAVE: PAINTINGS, IMAGES, SPIRITUALITY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST SCULPTURES factsanddetails.com ;

VENUS STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Introduction to Paleolithic Cave Paintings in Northern Spain” by Cesar Gonzales Sainz, Roberto Cacho Toca, et al. Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Altamira” by Matilde Muzquiz Perez-Seoane, Frederico Bernaldo de Quiros (1999) Amazon.com;

“What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity” by Jean Clottes Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008) Amazon.com;

“The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist Amazon.com;

“The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art” by Paul Bahn (2017) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art (World of Art)” (2017) by Bruno David Amazon.com;

“Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe” by Paul Bahn Amazon.com;

“Images of the Ice Age” by Paul G. Bahn Amazon.com;

“The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art” by David Lewis-Williams (2004) Amazon.com;

“Stepping-Stones: A Journey through the Ice Age Caves of the Dordogne” by Christine Desdemaines-Hugon (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs” by Mario Ruspoli (1987) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave” by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps (1996) Amazon.com;

“Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times” by Jean Clottes (2003) Amazon.com;

Cave Paintings with Hand Stencils and Prints in Spain

1) El Castillo Cave, Spain (c.37,300 B.C.): More very old hand stencils come from the Aurignacian cave complex of El Castillo. Some 55 other hand silhouettes and other symbols can be seen in the cave, several of which have also been dated to the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic. Since this period of early Aurignacian art coincides with the first arrival of anatomically modern man, speculation has arisen that these hand paintings were made by Neanderthals. Sceptics consider this unlikely.

2) Maltravieso Cave, Spain (c.18,000 B.C.): This centre of Solutrean art at Caceres, Extremadura, contains numerous animal paintings and engravings as well as an outstanding cluster of 71 stencilled handprints, many of which are missing fingers.

3) La Garma Cave, Spain (c.17,000 B.C.): There are 32 hand stencils, plus a series of red dots and other simple red ochre animal figures from the era of Solutrean art, which span the entire length of the cave's 300 meter Lower Gallery.

4) Altamira, Spain (c.17,000 B.C.): Amongst its other examples of parietal art, this famous Cantabrian rock shelter boasts a number of hand stencils sprayed with red pigment.

40,800-Year-Old “Panel of Hands” in El Castillo Cave

According to National Geographic: Some of the oldest known paintings in the world are in the Cave of the Castle (El Castillo) in Cantabria in the north of Spain. Thought to be more than 40,000 years old, many of the images are stencils of ancient hands made by artists blowing paint from their mouths. [Source: National Geographic]

The 'Panel of Hands' in El Castillo Cave is a series of red disks and hand stencils made by blowing or spitting paint onto the wall. A date from a disk shows the painting to be older than 40,800 years making it among the oldest known cave art in Europe. Some bison overlay the hands and are therefore painted later. [Source: Seth Borenstein, Associated Press, June 14, 2012]

Seth Borenstein of Associated Press wrote: “Testing the coating of paintings in 11 Spanish caves, researchers found that one is at least 40,800 years old, which is at least 15,000 years older than previously thought. That makes them older than the more famous French cave paintings by thousands of years. Scientists dated the Spanish cave paintings by measuring the decay of uranium atoms, instead of traditional carbon-dating, according to a report released Thursday by the journal Science. The paintings were first discovered in the 1870s.

“The oldest of the paintings is a red sphere from a cave called El Castillo. About 25 outlined handprints in another cave are at least 37,300 years old. Slightly younger paintings include horses. Cave paintings are "one of the most exquisite examples of human symbolic behavior," said study co-author Joao Zilhao, an anthropologist at the University of Barcelona. "And that, that's what makes us human." There is older sculpture and other portable art. Before the latest test, the oldest known cave paintings were those France's Chauvet cave, considered between 32,000 and 37,000 years old.”

A novel dating technique was used to date the Spanish cave art. Jason Daley wrote in Discover: “Measuring the age of the cave paintings found across Europe is confounding because most images are made from inorganic pigments that leave few clues. Archaeologist Alistair Pike, now at the University of Southampton, described a clever way to get answers: Analyze the breakdown of radioactive uranium-234 embedded in the natural mineral crust that forms on top of the artworks. Pike and his team applied the technique to drawings from 11 caves in the Cantabria and Asturias regions of northern Spain. They pegged the age of one illustration—a red disk in El Castillo cave—at 40,800 years old, making it the oldest known piece of European art by more than 5,000 years. [Source: Jason Daley, Discover, January 2, 2013

Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Rather than directly examining the art, scientists instead analyzed calcium carbonate (calcite) crusts that covered the paintings. They used a technique called uranium-thorium dating. The calcite covering, which is formed by the same process as stalagmites and stalactites, contains trace amounts of uranium, which decays over time into thorium. Using mass spectrometry, scientists can measure thorium in a calcite sample as small as a grain of rice to arrive at an approximate date when the crust formed. That date is the minimum possible age of the art behind it.” [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, Volume 65 Number 5, September/October 2012]

40,800-Year-Old Spanish Cave Art: Made by Neanderthals or Humans?

The painted works described above may predate the arrival of modern humans in the area the artworks were made, therefore it would not be presumptuous to presume they might have been made by Neanderthals. The earliest remains of modern humans in Europe is a 41,500-year-old mandible found in the Romanian cave Pestera cu Oase. The earliest fossils of Neanderthals in Europe are dated at 430,000 years ago. If modern humans made the art works, it would safe to assume they arrived with some already-developed artistic skills, although there evidence of cave art in Africa older than 40,000 years old.

Seth Borenstein of Associated Press wrote: “What makes the dating of the Spanish cave paintings important is that it's around the time when modern humans first came into Europe from Africa. Study authors say they could have been from modern humans decorating their new digs or they could have been the working of the long-time former tenant of Europe: the Neanderthal. Scientists said Neanderthals were in Europe from about 250,000 years ago until about 35,000 years ago. Modern humans arrived in Europe about 41,000 to 45,000 years ago — with some claims they moved in even earlier — and replaced Neanderthals. "There is a strong chance that these results imply Neanderthal authorship," Zilhao said. "But I will not say we have proven it because we haven't." [Source: Seth Borenstein, Associated Press, June 14, 2012]

Zilhao said Neanderthals recently have gotten "bad press" over their abilities. They decorated their tools and bodies. So, he said, they could have painted caves. But there's a debate in the scientific community about Neanderthals. Other anthropologists say Zilhao is in a minority of researchers who believe in more complex abilities of Neanderthals.

“Eric Delson, a paleoanthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and John Shea at Long Island's Stony Brook University said the dating work in the Science paper is compelling and important, but they didn't quite buy the theory that Neanderthals could have been the artists. "There is no clear evidence of paintings associated with Neanderthal tools or fossils, so any such evidence would be surprising," Delson said. He said around 41,000 years ago Neanderthals were already moving south in Europe, away from modern humans and these caves. Shea said it is more likely that modern humans were making such paintings in Africa even earlier, but the works didn't survive because of the different geology on the continent. "The people who came in to Europe were very much like us. They used art, they used symbols," Shea said. "”

In order to prove Neanderthals were cave artists, Delson believes archaeologists need to find bones or tools in a cave layer that corresponds directly to the art on a wall. Zilhão disagrees. "You don't have to have both the art and the occupation in the same site," he says, noting that there are no associated human remains at caves famous for their Paleolithic art, such as Chauvet. "These are just places where people went to make this stuff." [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, Volume 65 Number 5, September/October 2012]

See Separate Article: NEANDERTHAL ART: PAINTINGS, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com

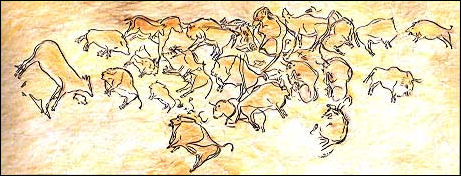

Altamira images

Altamira Cave

Altamira Cave, a mile from Santilla der Mar, in Spain is one the two most famous prehistoric caves (Lascaux is the other). Occupied between 10,000 and 15,000 B.C. by Paleolithic modern humans, the cave contains stone age painting similar to those in Lascaux Caves in France. Described as the "Sistine Chapel of the Ice Age," the caves house spectacular paintings of bison, deer and hunters.

The highlight of the cave is a set of paintings, at least 14,000 years old, of red and yellow bison plus horses, deer, humans with the heads of animals and mysterious symbols. UNESCO listed the paintings as a World Heritage Site in 1985, describing them as "masterpieces of creative genius and... humanity's earliest accomplished art." [AFP]

One of the most famous paintings features a wounded bison collapsed on the ground with it head lowered in defense. The Great Hall of Altamira featured 21 bisons painted red and black, who appear the be charging against a low limestone wall. The nearby caves, Cuevas del Castillo and Cuevas de al Monedas in Puetre Viego, also contain impressive cave paintings and engravings. Tito Bustillo cave in Ribadesell has drawing that are several thousand years old.

Labastide is an ancient cave in the Pyrenees. The entrance is a huge rocky hole at the bottom of a pit. It contains 200 paintings and engravings in a labyrinth of galleries extending for a third of a mile into the Earth. More than 80 of the figures are concentrated about 200 meters from the entrance. Further inside are 60 engravings, including horses, bison, human figures, an ibex, and many other animals. The most outstanding painting is six-foot-long horse with a wonderfully rendered head and body.

According to UNESCO: “Seventeen decorated caves of the Paleolithic age were inscribed as an extension to the Altamira Cave, inscribed in 1985. The property will now appear on the List as Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain. The property represents the apogee of Paleolithic cave art that developed across Europe, from the Urals to the Iberian Peninusula, from 35,000 to 11,000 BC. Because of their deep galleries, isolated from external climatic influences, these caves are particularly well preserved. The caves are inscribed as masterpieces of creative genius and as the humanity’s earliest accomplished art. They are also inscribed as exceptional testimonies to a cultural tradition and as outstanding illustrations of a significant stage in human history.” [Source: UNESCO ]

Discovery of Altamira Cave

Altamira Cave entrance

Altimira Cave was discovered in 1868 by a Spanish nobleman, while hunting on his estate in Santander province. After his dog had taken off in pursuit of a fox it had fallen into the narrow opening of the cave. Following the sound of the dog's barking the noblemen squeezed into the caves but didn't find the paintings.

In 1875, the owner of the land, Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, inspired by collection of prehistoric tools he saw in Paris, began exploring the caves. One day in the summer of 1879 his 11-year-old daughter squeezed through the entrance of a low-ceiling cave that was difficult for Sautoula to get through. "Papa, look at the painted bulls!," she exclaimed. Sautoula followed her and saw a series of painting of bison that he instantly recognized as having been extinct in this region since Paleolithic times. Sautuola wrote academic papers on his findings but was ridiculed by eminent archaeologist of his time and accused of art forgery.

Parts of Niaux and Mas d-Azil, two large painted caves in the Pyrenees has been known for centuries but the images were thought to have been rendered in historic times, perhaps by Roman legionaries. Cave art was not really taken seriously until the discovery of the Les Combarellas Cave and Font-de-Gaum cave (with its famous renderings of two lovesick reindeer) were discovered in the late 1800s.

Altamira Cave Controversy

Altamira doe Even though the style of the paintings was similar to the small sculptures made of reindeer antlers found in prehistoric caves in France, scholars considered the cave paintings fakes because they contained no actual depictions of reindeer and they were thought to be too good to have been made by ancient man. Some scholars even suggested that de Sautuola hired a French painter friend to make the paintings. He still had not been vindicated at the time of his death in 1888.

De Sautuola was finally vindicated when paintings similar to those in Altamira Cave were found in 1895 in the Grotte de la Mouthe in the Dordogne region of southern France. These paintings were discovered accidentally by local boys who crawled 100 meters into the cave and they found pictures of animals on the walls and ceiling.

In 1901, more caves were discovered in Dordogne, at Combarelles and Font-de-Gaume. One of the men who had called de Sautuola a fraud wrote in 1902 that he was "party to a mistake of twenty years" and "an injustice which frankly must be admitted and put right."

Cueva del Pindal and Other Caves in Northern Spain

Miranda S. Spivack wrote in the Washington Post: “The Spanish guide unlocked the gate in the stone wall and pointed the way with a flashlight. Though it was a hot, dry summer day, we were entering a world where ice once enveloped the land and long-extinct beasts roamed the forests. And there, just a few dozen yards away, was the evidence: the unmistakable image of a mammoth, about three feet across, outlined in red. For 3 euros each, with 10 other visitors, we were visiting Cueva del Pindal, one of Spain’s foremost prehistoric cave sites. It’s on the northern coast, with the Cantabrian Sea crashing against the rocks a hundred yards away. We stepped through the metal gate into a dark, damp, chilly cavern more than three football fields long. [Source: Miranda S. Spivack, Washington Post, October 30, 2014 ^||^]

“A short walk from the mammoth were half a dozen well-drawn paintings of deer, horses, bison and a fish. There were also bunches of vertical lines and dots, perhaps denoting the passage of time, but whose significance is still being debated by experts and may never be known. They are thought to be 13,000 to 20,000 years old. ^||^

“Other caves in the north of Spain open to the public include Las Monedas, a short walk from El Castillo, with a dramatic black bison standing on its hind legs; and the more recently discovered El Pendo, less than 10 miles from the north coast city of Santander and the source of a number of impressive pieces of portable art now housed in the Santander regional museum. The cave itself bears a single panel of several beautifully painted deer. ^||^

“The caves of Asturias and Cantabria that are open to the public admit a limited number of visitors daily and only in small groups by reservation. Sturdy shoes are a must; if flashlights are required, the staff will provide them. Reservations can be made on the Internet or by calling the cave’s visitors office (knowing basic Spanish is helpful). In almost every cave we visited, the universally enthusiastic guides spoke only Spanish, and often there are few, if any brochures in English. Sometimes the guides knew English but were hesitant to use it; you can try asking questions in English if you can’t speak Spanish.” ^||^

Cave art sites in southern France and northern Spain

Cueva de la Pileta in Southern Spain

Miranda S. Spivack wrote in the Washington Post: “On a different trip across the province of Málaga, in southern Spain, we stopped in the ancient city of Ronda for the night (fantastic gorge, beautiful old buildings, Arab baths). The next day, we drove to the rural village of Benaojan, where a small sign directed us up a dirt road to La Pileta, one of the few privately owned, open-to-the-public caves with paintings in Spain. [Source: Miranda S. Spivack, Washington Post, October 30, 2014 ^||^]

“We parked in a dirt lot with a few other cars and walked up a steep trail and stone steps that ended by the mouth of the cave. A roofed picnic area beside a small, unoccupied cabin provided shelter from the sun. Near 1 p.m., the time of our tour, the cave’s iron door opened; a few people emerged squinting at the sun. They were followed by the cave’s guardian and tour guide, Tomas Bullon, the great-grandson of Jose Bullon, who discovered the cave in 1905. ^||^

“Bullon, who is trying — so far, without success — to persuade his 17-year-old son to join this family business, led us through the cave opening into a small gift shop lit only by his battery-powered lantern. He collected the entry fee of 3 euros each and handed out a few more lanterns. Then he told us the rules: No photos once we left the shop area — the flash is bad for the art, and the sensors are bad for the bats, he said, and no touching anything (standard rules in such caves). Inside, the cave was wet and cool. Water dripped from stalactites formed over thousands of years. Bullon was eager to speak in English, a rare but welcome opportunity for us. Along with some British tourists, we took him up on it. ^||^

“Cueva de la Pileta’s art is mostly black and red paintings of horses, deer and one enormous fish. The art is thought to be about 25,000 years old. Although most cave ceilings are high, and the claustrophobia factor is low, some people prefer to see art outdoors. Throughout Spain and in neighboring Portugal are several impressive pieces of stone and outdoor sculptures that were carved with primitive tools but often with great artistry. ^||^

“For those looking to combine ancient art with an outdoor adventure, try hiring a private guide to take you to Cueva de la Laja Alta to see the oldest known representation of a boat on the Iberian peninsula. (We found our guide through the owner of our hotel, Hostal el Anon.) After a half-hour drive along winding and, ultimately, dirt roads to the top of an Andalucian hill outside of Jimena de la Frontera (stunning view of the Mediterranean included) our guide took us on a three-hour-long bushwhack through a cork forest. We finally arrived at an abrigo, where the painting is behind iron bars to protect it from vandals. It was made during the Chalcolithic period, or Copper Age, between 5,000 and 8,000 years ago. Standing a few feet away, we could make out the somewhat faded outline of a red boat.” ^||^

Siega Verde on the Spain-Portugal Border

Miranda S. Spivack wrote in the Washington Post: “Siega Verde, on Spain’s border with Portugal, and Côa Valley, in Portugal, offered greater accessibility than any cave we visited. There we saw small and large animal figures carved in stone that rivaled anything we saw in caves. And there is a bonus — you can take pictures. [Source: Miranda S. Spivack, Washington Post, October 30, 2014 ^||^]

“Originally, Siega Verde was not high on our list of places to visit, and we didn’t even know about the Côa Valley. We added Siega Verde to a trip through Castilla y Leon visiting mostly Roman remains. The site is a short drive from Ciudad Rodrigo (which has an old city that itself is worth a visit), but we gave ourselves plenty of time, since road signs often disappear just when you need them most in Spain, and visits were by appointment only. ^||^

“With a guide and a few other visitors, we walked along a short trail to the river’s edge and viewed some of the most spectacular early art we had seen in Spain — large and small figures of horses, deer, and cows or bulls carved or pecked into rock. The carvings date to at least 12,000 years ago and are remarkably similar to the animal figures of the cave art that we had seen. We saw a dozen or so fine carvings. ^||^

“The guide advised us that there was more to see in nearby Côa Valley. “Nearby” turned out to be something of an exaggeration, especially with a GPS unit that kept taking us in circles through small Portuguese villages. We considered giving up since we hadn’t booked a tour in advance. We soldiered on, however, and were richly rewarded. The Côa site is huge — something like 4,000 identified drawings and carvings — though visitors are permitted to see only a few. Our visit started at the starkly modern museum that sits high above the Côa River where it meets the Douro in the heart of the Douro wine country. Our guide took us and a couple from Belgium down to the valley in a four-wheel-drive vehicle. The art was as impressive as Siega Verde, and there is more of it. The archaeological park has two separate sites and each has different tours, including at night. Hotel options were not great, but the museum has an excellent restaurant, with a great view.” ^||^

Côa Valley and Siega Verde: Outdoor Prehistoric Rock Art

Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde together are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. According to UNESCO: “The two Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in the Côa Valley (Portugal) and Siega Verde (Spain) are located on the banks of the rivers Agueda and Côa, tributaries of the river Douro, documenting continuous human occupation from the end of the Paleolithic Age. Hundreds of panels with thousands of animal figures (5,000 in Foz Côa and around 440 in Siega Verde) were carved over several millennia, representing the most remarkable open-air ensemble of Paleolithic art on the Iberian Peninsula. [Source: UNESCO UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“The Côa Valley and Siega Verde sites consist of rocky cliffs carved by fluvial erosion and embedded in an isolated rural landscape in which hundreds of panels with thousands of animal figures. The rock-art sites of Foz Côa and Siega Verde represent the most remarkable open-air ensemble of Palaeolithic art on the Iberian Peninsula within the same geographical region. Foz Côa and Siega Verde provide the best illustration of the iconographic themes and organization of Palaeolithic rock art, which adopted the same modes in caves and in the open air, thus contributing to a greater understanding of this artistic phenomenon. Together they form a unique place of the prehistoric era, rich in material evidence of Upper Palaeolithic occupation. =

The site important because: 1) The rock engravings in Foz Côa and Siega Verde, dating from the Upper Palaeolithic to the final Magdalenian/ Epipalaeolithic (22,000 – 8.000 BCE), represent a unique example of the first manifestations of human symbolic creation and of the beginnings of cultural development which reciprocally shed light upon one another and constitute an unrivalled source for understanding Palaeolithic art. 2) The rock art of Foz Côa and Siega Verde, when considered together, throws an exceptionally illuminating light on the social, economic, and spiritual life of our early ancestors. =

“The integrity of the property is expressed primarily by the homogeneity and continuity in development within the spatial limits of the engraved rock surfaces as well as by the adoption of the typical patterns of prehistoric paintings inside caves, thus confirming the argument for the integrity of this outdoor ensemble. “The authenticity of the property is demonstrated by stylistic and comparative considerations, which also include the examination of artistic themes and organization of rock engravings in caves. The only doubts relate to the interpretation of certain animal figures (e.g. woolly rhinoceros, bison, megaceros deer, reindeer, and felines). =

Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin on the Iberian Peninsula

Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin on the Iberian Peninsula is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. According to UNESCO: “The Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin on the Iberian Peninsula is the largest group of rock-art sites anywhere in Europe, and provides an exceptional picture of human life in a critical phase of human development, which is vividly and graphically depicted in paintings that are unique in style and subject matter [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“Prehistoric Levantine rock art sites are found in the coastal and inland mountain ranges of the Mediterranean Basin of the Iberian Peninsula over 1,000 kilometres of coast, from Catalonia to Andalusia. The property includes 758 sites distributed across six Autonomous Communities - Andalusia, Aragón, Castilla-La Mancha, Catalonia, Murcia, and Valencia - located in scarcely populated areas with high ecological and landscape values. =

“The paintings are found in shallow open-air shelters, on front walls and sometimes on the ceilings of the shelters. They have a number of regional variations, which are not always easy to distinguish. The northern zone has mainly single, naturalistic zoomorphic figures and rare stylized human figures. The Maestrazgo and Lower Ebro zones include representations of dynamic hunting and combat scenes containing human figures. The mountain areas of Cuenca and Albarracín have paintings in shelters and siliceous rocks, while the Júcar river cave and neighbouring mountain area have depictions of action-filled hunting scenes. The paintings in the Safor and La Marina regions (Valencia and Alicante) depict hunting and social scenes but no combat, while in the Segura River basin and neighbouring mountain areas zoomorphism predominates. Finally, in Eastern Andalusia, the Los Vélez region and the foothills of the Sierra Morena, paintings include mostly zoomorphic figures. =

“The figures are simple silhouettes or roughly filled in with a pigment and outlined. The predominant colours are red, black and to a lesser extent, white and yellow. Their fine lines of between 1 and 3 mm thick were done with quills and/or elements from plants. The figures were sometimes filled in with spot colours. =

“The scenes depicted are the first narrations of European Prehistory, and they provide us with very relevant information about the following aspects: Individual or group hunting activities; trapping and tracking of wounded animals; harvesting, such as honey, an outstanding historical reference of beekeeping; the first evidence of organized military confrontations; combats and executions; scenes from daily life, which provide us with information about their clothes and personal adornments marking social differences during Prehistory; funeral rites and scenes of rituals; witch doctors, feminine divinity, and figures that combine human and animal characteristics (amongst the human figures, archers are the most common as well as women and children); zoomorphic figures, single objects, or abstract motifs. =

“Likewise, the survival of the indigenous fauna gives the exceptional quality of a timeless landscape to these areas, as these places constitute the last reserves of certain threatened species of animals in Europe, such as the Golden Eagle, Bonelli’s Eagle or the Peregrine Falcon. Also, the rarest of European mammals are still present, such as the Iberian lynx or the Spanish ibex. =

“The Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin on the Iberian Peninsula constitutes an exceptional historical document due to its broad range and provides rare artistic and documentary evidence of the socio-economic realities of prehistory. It is exclusive to the Mediterranean basin of the Iberian Peninsula due to the complexity of the cultural processes in this region in later prehistory and factors related to conservation processes, such as the nature of the rock and specific environmental conditions as well as the range of subjects depicted and techniques employed.” =

Art in Cova Dones in Valencia

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology: Deep inside Cova Dones, a cave in the province of Valencia in Spain, archaeologists have found more than 110 paintings and engravings, some of which they have dated to almost 25,000 years ago. The artworks depict geometric motifs and animals including female red deer, wild horses and aurochs. Claw marks on the cave walls, some of which are scratched into the artwork, belong to a species of cave bear that went extinct around 24,000 years ago. The style of the incised and painted figures is similar to artwork in other Iberian caves that is known to have been made more than 20,000 years ago. A team of researchers led by archaeologist Aitor Ruiz-Redondo of the University of Zaragoza dated the paintings and engravings based on these stylistic features and the presence of the claw marks. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology , March/April 2024

Paleolithic artists created the works using two techniques rarely seen in rock art of the period in the area. They incised some of the figures by scraping lines into limestone that had accumulated on the wall surfaces, a process that has not been documented elsewhere in eastern Iberia. The paintings were produced by smearing iron-rich red clay from the cave floor onto the walls, another technique not common in the area. Water in the cave has a high lime content, which caused it to act as a kind of natural paint fixative. “The drying process was probably rather slow, as the environment of the cave is quite humid,” Ruiz-Redondo says. “This gave time for calcite layers to form that covered some parts of the paintings, preserving them until now.”

Cova Dones is located on Spain’s eastern coast in Valencia, whereas most of the Spain’s cave art — including Altamira — is in northern Spain. It was first explored by Ruiz-Redondo and colleagues in 2021. Sonja Anderson wrote in Smithsonian magazine, Unlike other Paleolithic paintings, typically made with ocher or manganese, most of Cova Dones’ paintings were done in clay — and conserved by chemistry. Early humans likely scooped red clay from the cave’s floor and walls, mixing it with water at their feet. They were — inadvertently or not — creating a minerally reinforced paint. Then, thousands of years of water trickling into the cave deposited a layer of calcium carbonate over their work, sealing it to the wall for Ruiz-Redondo to find so many centuries later. [Source: Sonja Anderson, Smithsonian magazine, January/February 2024

Determining the age of cave art is delicate work. Ruiz-Redondo and his team are awaiting a full laboratory analysis of Cova Dones’ motifs — including radiometric dating of their crusty mineral coverings — but until then, a couple of logical approaches provide some clarity. First, some of the motifs are drawn in a style that’s typical of a period about 21,000 to 40,000 years ago, according to dating at other Paleolithic sites, Ruiz-Redondo says. Second, one of the drawings was defaced in a telling way: “It was covered by a bear scratch,” Ruiz-Redondo says. The mark was made by a cave bear, an animal that went extinct 24,000 years ago, and its placement allows the team to determine that the motif predates the bear’s extinction.

14,000-Year-old Paintings Found 300 Meters Underground in Spain

In 2016, Fox News Latino reported: “Archaeologists in northern Spain have discovered deep in a cave a series of cave paintings dating as far back as 14,000 years. Scientists said they found around 70 paintings nearly 1,000 feet underground in the Basque Country’s Atxurra cave. [Source: Fox News Latino, June 14, 2016 ***]

“While the site was first discovered in 1929, the cave’s depth made it difficult to explore. The latest discovery, which began in 2014, has been described by head archaeologist Diego Garate as “an exceptional find, the equivalent of discovering a lost Picasso.” “Discoveries of this caliber are not made every year, at most, once a decade,” Garate told The Local. “It is important because of the quantity of figures depicted, their excellent conservation and for the presence of associated archeological materials such as charcoal and flint tools.” ***

“The drawings include hunting scenes and pictures of horses, bison, deer, and goats. The cave also wins the distinction of being the home of the drawing of a bison with the most spear markings found in Europe yet , as the cave holds a painting of one bison is pierced with — over 20 spears. The discovery of the paintings also gives credence to Spain as one of Europe’s hot spots for cave art, adding to a list that includes the famed Upper Paleolithic drawings in Altamira to the recently found ones in the Cantabria region that are 20,000 years old.” ***

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except the stingray from ZME science and the Cova Dones from Eden Gallery

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024