Home | Category: First Modern Human Art and Culture

CHAUVET CAVE

On Christmas Eve, 1994, three spelunkers — Jean-Marie Chauvet and his friends Elitte Brune and Christian Hillaire — made one of the greatest archaeological discoveries ever inside a cave near Pont-d'Arc in the Ardéche region of southern France, an area popular with cavers. The cave is officially named Chauvet-Pont d’Arc. [Source: Jean Clottes, National Geographic, August 2001]

What the spelunkers found was Chauvet Cave, named after one of its discoverers."Tears were running down my cheeks," Jean Clottes, France foremost expert on cave art, said of his first glimpse of the paintings. "I was witnessing one of the world's greatest masterpieces...I was so overcome...It was like going into an attic and finding a da Vinci. except that the great master was unknown."

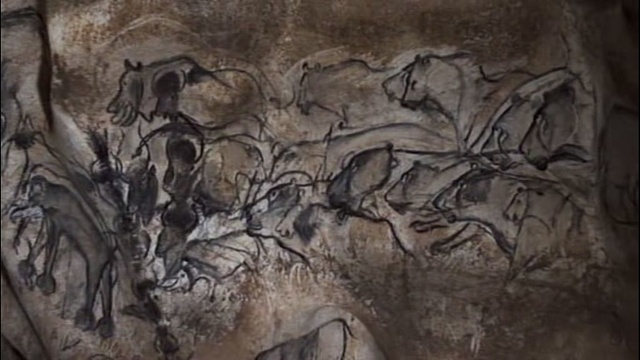

Chauvet Cave is regarded as more impressive and beautiful than Lascaux cave by people who have seen both. Chauvet contains stone engravings and paintings with 420 animal figures. Some paintings are 35,000 years old paintings, some of the oldest cave paintings known to science. The images are almost twice as old and more than twice as large as the images in Lascaux and Altamira.

According to UNESCO: “Located in a limestone plateau of the Ardèche River in southern France, the property contains the earliest-known and best-preserved figurative drawings in the world, dating back as early as the Aurignacian period (30,000–32,000 BP), making it an exceptional testimony of prehistoric art. The cave was closed off by a rock fall approximately 20,000 years BP and remained sealed until its discovery in 1994, which helped to keep it in pristine condition. Over 1,000 images have so far been inventoried on its walls, combining a variety of anthropomorphic and animal motifs. Of exceptional aesthetic quality, they demonstrate a range of techniques including the skilful use of shading, combinations of paint and engraving, anatomical precision, three-dimensionality and movement. They include several dangerous animal species difficult to observe at that time, such as mammoth, bear, cave lion, rhino, bison and auroch, as well as 4,000 inventoried remains of prehistoric fauna and a variety of human footprints. [Source: UNESCO =]

Websites and Resources on Prehistoric Art: Chauvet Cave Paintings archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet ; Cave of Lascaux archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en; Trust for African Rock Art (TARA) africanrockart.org; Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com; Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology, by Peter Brown peterbrown-palaeoanthropology.net

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RELATED ARTICLES:

CHAUVET CAVE DISCOVERY, STUDY, FILMING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S EARLIEST ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CAVE ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WHY EARLY HUMANS MADE ART factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

IMAGES IN EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART: ANIMALS, HAND PRINTS, FIGURES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL ART, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEARS OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

CAVE ART IN SPAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAVE ART IN FRANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LASCAUX CAVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST SCULPTURES factsanddetails.com ;

VENUS STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times” by Jean Clottes (2003) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave” by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs” by Mario Ruspoli (1987) Amazon.com;

“Stepping-Stones: A Journey through the Ice Age Caves of the Dordogne” by Christine Desdemaines-Hugon (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Altamira” by Matilde Muzquiz Perez-Seoane, Frederico Bernaldo de Quiros (1999) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008) Amazon.com;

“What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity” by Jean Clottes Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist Amazon.com;

“The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art” by Paul Bahn (2017) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art (World of Art)” (2017) by Bruno David Amazon.com;

“Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe” by Paul Bahn Amazon.com;

“Images of the Ice Age” by Paul G. Bahn Amazon.com;

“The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art” by David Lewis-Williams (2004) Amazon.com;

Layout and Contents of Chauvet Cave

Chauvet Cave location

Chauvet Cave is five times larger than Lascaux Cave. According to UNESCO: “The decorated cave of Pont d’Arc, known as Grotte Chauvet-Pont d’Arc is located in a limestone plateau of the meandering Ardèche River in southern France, and extends to an area of approximately 8,500 square meters. [Source: UNESCO =]

The Chauvet Cave cave complex consists a string of chambers that are 570 meters long and a connecting gallery and three vestibules. The largest chamber is 70 meters long and 40 meters wide. The distance between the entrance and the furthest images are about 250 meters. At the northern end the cave forks into two horn-shaped branches. In the chambers where the art is found the ceiling varies in height from about 1½ meter to 13 meters. There are some passages that require adults to kneel or crawl.

Jean Clottes wrote in for The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The cave is extensive, about 400 meters long, with vast chambers. The floor of the cave is littered with archaeological and palaeontological remains, including the skulls and bones of cave bears, which hibernated there, along with the skulls of an ibex and two wolves. The cave bears also left innumerable scratches on the walls and footprints on the ground. [Source: Jean Clottes, Independent Scholar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2002 \^/]

“The two major parts of the cave were used in different ways by artists. In the first part, a majority of images are red, with few black or engraved ones. In the second part, the animals are mostly black, with far fewer engravings and red figures. Obvious concentrations of images occur in certain places. The most spectacular images are the Horse Panel and the Panel of Lions and Rhinoceroses. \^/

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine, “The primary residents were a now-extinct species of bear and that feces and rotting carcasses of bears that died while hibernating — in addition to smoke from torches and fires lit by the artists — would have made up the atmosphere. More than 190 cave bear skulls have been found in Chauvet Cave. One was placed at the edge of a large stone block. Why remains a mystery. Some of the paintings in Chauvet Cave incorporate claw marks left by bears, making the art an interspecies collaboration. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2011]

Dating the Art in Chauvet Cave

“After the cave paintings were discovered in December 1994," Zorich wrote, " the first question archaeologists faced was, how old are they? At first glance, the paintings' technical sophistication made them seem relatively recent, perhaps 10,000 to 15,000 years old. Radiocarbon dating of the charcoal in the black pigments, however, showed that the earliest paintings in the cave were made 35,000 years ago. The date overturned the idea that Europe's earliest cave paintings were crude and simple and that artistic techniques had to be refined over thousands of years before the finest cave art could be made. More than 80 radiocarbon dates have been taken from the torch marks and paintings on the walls, as well as the animal bones and charcoal that litter the floor, providing a detailed chronology of the cave. The dates show that the artwork was made in two separate periods, one 35,000 and one 30,000 years ago. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2011]

Jean Clottes wrote in for The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Thirty radiocarbon datings made in the cave have shown that it was frequented at two different periods. Most of the images were drawn during the first period, between 30,000 and 32,000 BP in radiocarbon years. Some people came back between 25,000 to 27,000 and left torch marks and charcoal on the ground. Some human footprints belonging to a child may date back to the second period. [Source: Jean Clottes, Independent Scholar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2002]

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Arguments for the accuracy of the dating got a boost” in 2011 “when Jean-Marc Elalouf at the Institute of Biology and Technology in Saclay, France, conducted DNA studies and radiocarbon dating of the remains of cave bears (Ursus spelaeus) that ventured inside the grotto to hibernate during the long ice age winters. Elalouf determined that the cave bear skeletal remains were between 37,000 and 29,000 years old. Humans and bears entered the cave on a regular basis—though never together—before the rock fall. “Then, 29,000 years ago, after the rock slide, they couldn’t get inside anymore,” says Clottes.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015]

Chauvet Cave has a cool, damp climate with temperatures at a constant 56̊F and a humidity level of 99 percent. These conditions account for its remarkable state of preservation. It appears that only a bears entered the cave between the time the last paintings were created and the time the cave was rediscovered in the 1990s.

Why Chauvet Cave is So Great

According to UNESCO: Chauvet Cave “contains the best-preserved expressions of artistic creation of the Aurignacian people, constituting an exceptional testimony of prehistoric cave art. In addition to the anthropomorphic depictions, the zoomorphic drawings illustrate an unusual selection of animals, which were difficult to observe or approach at the time. Some of these are uniquely illustrated in Grotte Chauvet. As a result of the extremely stable interior climate over millennia, as well as the absence of natural damaging processes, the drawings and paintings have been preserved in a pristine state of conservation and in exceptional completeness. [Source: UNESCO =]

Chauvet Cave is important because: 1) it “contains the first known expressions of human artistic genius and more than 1,000 drawings of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs of exceptional aesthetic quality have been inventoried. These form a remarkable expression of early human artistic creation of grand excellence and variety, both in motifs and in techniques. The artistic quality is underlined by the skilful use of colours, combinations of paint and engravings, the precision in anatomical representation and the ability to give an impression of volumes and movements. =

2) “The cave bears a unique and exceptionally well-preserved testimony to the cultural and artistic tradition of the Aurignacian people and to the early development of creative human activity in general. The cave’s seclusion for more than 20 millennia has transmitted an unparalleled testimony of early Aurignacian art, free of post-Aurignacian human intervention or disturbances. The archaeological and paleontological evidence in the cave illustrates like no other cave of the Early Upper Palaeolithic period, the frequentation of caves for cultural and ritual practices.” =

Artistry at Chauvet Cave

The images in Chauvet Cave turned many interpretations about early man art on its head, especially those that viewed art history as a Darwinian progression from the primitive to the advanced: many of the works at Chavet are more sophisticated than works that appeared more than 10,000 years later.

The paintings are drawn with yellow ocher, charcoal and iron oxide and show the use of shading and perspective. Some even incorporate dots like Seurat-style pointillism. One of the chambers has only red paintings and another has only murals drawn in black. Connecting the large chambers are smaller chambers, roughly four by five meters. The engravings vary in size from 80 centimeters to four meters across.

"There is sense of rhythm and texture that is truly remarkable," French cultural official Jean Béghain told Time magazine. One of the more than 50 rhinos some are shaded with black charcoal to express rudimentary perspective and others look like action-depicting multiple exposure photographs. A couple of hunched over spotted hyenas are shown standing over one another. The artists incorporated natural cracks in the cave in the horns on an ibex.

Gilles Tosello of the University of Toulouse carefully photographed the paintings, added sketches that showed different layers of work and put it in all in a computer for analysis. Describing some details in a group of horses he wrote in his book Chauvet Cave : “Once again, the surface was carefully scraped beneath the throat, which suggests to us a moment of reflection, or perhaps doubt...the last horse is unquestionably the most successful of the group, perhaps because the artist is by now certain of his or her inspiration. This forth horse was produced using a complex technique: the main lines were drawn with charcoal; the infill, colored sepia and brown, is a mixture of charcoal and clay spread with the finger...A series of fine engravings perfectly follow the profile. With energetic and precise movements, significant details are indicated (nostril, open mouth). A final charcoal line, dark black, was placed just at the corner of the lips and gives this head an expression of astonishment or surprise."

Near the first paintings of lions and owls are 92 human palm prints in the shape of a bison or rhino. Some archaeologists believe they may be the artist's signature. Analysis of the prints indicate they were made a single individual, who stood about 180 centimeters tall, using his right hand.

On the producing tracings of images in Chauvet Cave, Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine, “Studying the paintings is an intensive process that begins by going into the cave to photograph an image. The digital photograph is enlarged in the laboratory. Then a researcher places a sheet of transparent plastic over the photo and traces the image in as much detail as possible. The tracing is then brought inside the cave to check it against the original painting. At this stage the researchers also move a light at different angles around the painting to reveal any hidden details of the image. The process forces the researchers to put themselves in the place of the painters and understand the variety of techniques that were used to make the artwork. Some of the images were made after scraping away a layer of dark brown clay that covers the cream-colored limestone walls. Most were made by drawing with a piece of charcoal, or painting with a brush or finger covered in red pigment, or by spitting pigment against the wall. As the tracing is created, the research team learns how the images were composed and the order in which the lines were drawn. "People ask me, 'Why don't you use photos?'" says Clottes. "Well, a photo is not a study...the human mind is still the better computer."

Animal Images in Chauvet Cave

The paintings in the Chauvet Cave complex include images of herds of hooked-horned aurochs (wild oxen), ibex, running deer, charging wooly rhinoceros, prowling lions, rearing thick-maned horses, wooly mammoths, open-mouthed bears and animals that are usually associated with Africa not Europe. In all, there are 442 animals, created over thousands of years, using nearly 400,000 square feet of cave surface. Some animals are solitary or concealed but most are in groups, some of which look like great mosaics or multiple movie frames.

Jean Clottes wrote in for The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The dominant animals throughout the cave are lions, mammoths, and rhinoceroses. From the archaeological record, it is clear that these animals were rarely hunted; the images are thus not simple depictions of daily life at the time they were made. Along with cave bears (which were far larger than grizzly bears), the lions, mammoths, and rhinos account for 63 percent of the identified animals, a huge percentage compared to later periods of cave art. Horses, bison, ibex, reindeer, red deer, aurochs, Megaceros deer, musk-oxen, panther, and owl are also represented. An exceptional image of the lower body of a woman was found associated with a bison figure. Many images of large red dots are, indeed, partial handprints made with the palm of the hand. Red hand stencils and complete handprints have also been discovered. [Source: Jean Clottes, Independent Scholar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2002]

Unlike other caves in France and Spain which show mostly hunted animals such as bisons and oxen, the animals in Chauvet cave are large powerful animals that generally weren't eaten for food: lions, cave bears, rhinos. A wooly rhino is shown charging a herd of other rhinos and clashing with one of its members. Among the 72 cave lions one is depicted "sniffing the hindquarters of a crouched and snarling companion." The cave contains the first prehistoric cave paintings of a spotted leopard, a musk oxen and an owl turning its had 180 degrees.

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Spread out over six chambers spanning 1,300 feet were panels of lionesses in pursuit of great herbivores—including aurochs, the now-extinct ancestors of domestic cattle, and bison; engravings of owls and woolly rhinoceroses; a charcoal portrait of four wild horses captured in individualized profile, and some 400 other images of beasts that had roamed the plains and valleys in huge numbers during the ice age. With a skill never before seen in cave art, the artists had used the knobs, recesses and other irregularities of the limestone to impart a sense of dynamism and three-dimensionality to their galloping, leaping creatures. Later, Jean-Marie Chauvet would marvel at the “remarkable realism” and “aesthetic mastery” of the artworks they encountered that day. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ]

On the paintings that he found particularly striking or moving,the German filmmaker Werner Herzog said, “the Panel of the Horses and the Panel of the Lions, of course. The lions in particular are just incredible because a whole group of lions is looking, is stalking something. The intensity of their gaze, all looking exactly at something, focusing on something. You don't know exactly on what they focus and it has an intensity of art, of depiction, which is just awesome.” [Source: Archaeology magazine, March/April 2011]

Megaloceros Gallery and End Chamber

Describing the Megaloceros Gallery, Judith Thurman wrote in The New Yorker,"Huge, elklike herbivores...mingle on the walls with rhinos, horses, bisons, a glorious ibex, three abstract vulvas, and assorted geometric signs...It seems to have been a fathering point or a staging area where the artist built hearths to produce their charcoal."

Describing the Megaloceros Gallery, Judith Thurman wrote in The New Yorker,"Huge, elklike herbivores...mingle on the walls with rhinos, horses, bisons, a glorious ibex, three abstract vulvas, and assorted geometric signs...It seems to have been a fathering point or a staging area where the artist built hearths to produce their charcoal."

The End Chamber is a spectacular vaulted space with a third of the cave's etchings and paintings. Thurman wrote: “The paintings — a few in ocher, most in charcoal — are “all meticulously composed. A great frieze covers the back left wall: a pride of lions with Pointillist whiskers seem to be hunting a herd of bison, which appear to have stampeded a troop of rhinos, one of which looks as if it had fallen, or is climbing out of, a cavity in the rock... As at may sites , the scratches made by a standing bear have been overlaid with the palimpsest of signs or drawings, and one has to wonder if the carved art didn't begin with a recognition that bear claws were an expressive tool for engraving."

“To the far right of the freeze, on a separate wall, a huge, finely modeled bison stands alone, grazing stage left toward a pair of figures painted on a conical outcropping of rock that descends from the ceiling and comes to a point about four feet above the floor. The fleshy shape of this pendant is unmistakably phallic, and all of its sides are decorated."

On the End Chamber, Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Gazing through the murk, I studied one monumental panel, 36 feet long, drawn in charcoal. Sixteen lions on the far right sprang in pursuit of a panicking herd of buffalo. To the left, a pack of woolly rhinos thundered across the tableau. The six curving horns of one beast conveyed rapid movement—what Herzog had described as “a form of proto cinema.” A single rhino had turned to face the stampeding herd. I marveled at the artist’s interplay of perspective and action, half-expecting the menagerie to launch itself from the rock. I thought: They have been here.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

Imagining the Creators of Chauvet Cave

When asked if the people of Chauvet were artists or craftsmen, the German filmmaker Werner Herzog said, “In this case, you can clearly say this is art, and you can say it easily. It goes back to a time when there was, for example, no art market, no exhibitions, no galleries. No doubt in my heart that this is art, and it's some of the greatest that the human race ever created, period. It can't get any better, and it hasn't gotten much better. That's a great mystery." [Source: Archaeology magazine, March/April 2011]

Chip Walter wrote in National Geographic: “It is as if we are walking into the throat of an enormous animal. The tongue of a metal path arcs up and then drops downward into the blackness below. The ceiling closes in, and in some places the heavy cave walls crowd close enough to touch my shoulders. Then the flanks of the limestone open up, and we enter the belly of an expansive chamber. [Source:Chip Walter, National Geographic, January 2015]

“This is where the cave lions are. And the woolly rhinos, mammoths, and bison, a menagerie of ancient creatures, stampeding, battling, stalking in total silence. Outside the cave, where the real world is, they are all gone now. But this is not the real world. Here they remain alive on the shadowed and creviced walls.

“Around 36,000 years ago, someone living in a time incomprehensibly different from ours walked from the original mouth of this cave to the chamber where we stand and, by flickering firelight, began to draw on its bare walls: profiles of cave lions, herds of rhinos and mammoths, a magnificent bison off to the right, and a chimeric creature—part bison, part woman—conjured from an enormous cone of overhanging rock. Other chambers harbor horses, ibex, and aurochs; an owl shaped out of mud by a single finger on a rock wall; an immense bison formed from ocher-soaked handprints; and cave bears walking casually, as if in search of a spot for a long winter’s nap. The works are often drawn with nothing more than a single and perfect continuous line.”

Spiritual Purpose of Chauvet Cave

Many of the powerful animals are rarely seen in other prehistoric cave complexes, suggesting a religious purpose. Clottes told Newsweek, they appear to have "symbolized danger, strength and power" and the artist may have been attempting to capture "the essence of " the animals.

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “In 1996, two years after his first visit to Chauvet, Clottes published a seminal work, The Shamans of Prehistory, co-written with the eminent South African archaeologist David Lewis-Williams, that presented new ideas about the origins of cave art. The world of Paleolithic man existed on two planes, the authors hypothesized, a world of sense and touch, and a spirit world that lay beyond human consciousness. Rather than serving as dwellings for ancient man, Clottes and his colleague contended, caves such as Chauvet—dark, cold, forbidding places—functioned as gateways to a netherworld where spirits were thought to dwell. Elite members of Paleolithic societies —probably trained in the representational arts—entered these caves for ritualistic communion with the spirits, reaching out to them through their drawings. “You needed torches, grease lamps and pigment to go inside the caves. It was not for everyone. It was an expedition,” Clottes told me. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2015 ||/]

“As Clottes and his co-author interpreted it, the red-ocher handprints on the walls of Chauvet might well have represented attempts to summon the spirits out of the rock; the artists would likely have used the limestone wall’s irregularities not only to animate the animal’s features but also to locate their spirits’ dwelling places. Enigmatic displays found inside Chauvet—a bear cranium placed on an altarlike pedestal, a phallic column upon which a woman’s painted legs and vulva blend into a bison’s head—lend weight to the theory that these places held transformative power and religious significance. Clottes imagined that these primeval artists connected to the spirit world in an altered state of consciousness, much like the hallucinogen-induced trances achieved by modern-day shamans in traditional societies in South America, west Asia, parts of Africa, and Australia. He perceived parallels between the images that shamans see when hallucinating—geometric patterns, religious imagery, wild animals and monsters—and the images adorning Chauvet, Lascaux and other caves. ||/

“It was not surprising, says Clottes, that these early artists made the conscious choice to embellish their walls with wild animals, while almost entirely ignoring human beings. For Paleolithic man, animals dominated their environment, and served as sources of both sustenance and terror. “You must imagine the Ardèche Gorge of 30,000 years ago,” Clottes, now 81, says in his home study, surrounded by Tuareg knives and saddlebags, Central African masks, Bolivian cloth puppets and other mementos from his travels in search of ancient rock art. “In those days you might have one family of 20 people living there, the next family 12 miles away. It was a world of very few people living in a world of animals.” Clottes believes that prehistoric shamans invoked the spirits in their paintings not only to aid them on their hunts, but also for births, illnesses and other crises and rites of passage. “These animals were full of power, and the paintings are images of power,” he says. “If you get in touch with the spirit, it is not out of idle curiosity. You do it because you need their help.” ||/

Chauvet Cave, a Pilgrimage Site?

Chauvet Cave is filled with stalactites and stalagmites comprised of limestone and minerals that come in many shades and colors. The floors are littered with ursine remains. It seems a lot of cave bears hibernated here. Archaeologists had counted numerous bear wallows and 147 bears skulls in the cave, many of them dating back to the time when the paintings were made. Some of bears perhaps died naturally. Others maybe were eaten.

Chauvet contains human footprints, burnt bone fragments, napped flints, burned torches, and blackened hearths. Some archaeologist believe this is evidence indicates no people lived in the cave but visited again and again in a way that is consistent with a pilgrimage site.

Among the images with possible religious significance are semicircles of dots and a creature with human legs, the head and torso of a bison and a pubic triangles (possibly a fertility symbol). One of the most intriguing finds is bear cranium skull found resting on what appears to be a stone altar in a space called the Skull Chamber. Some of the bear bones and skulls are arranged in such a way that suggest ritual slaughter.

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine, “The way that people used Chauvet Cave was shaped by their interactions with the cave's primary residents, the now-extinct cave bear. Humans do not appear to have lived in the cave and it is likely that the paintings were made in the spring or summer when the bears would not have been hibernating. The bears themselves seem to have held a special significance for the artists who worked in the cave, in addition to being subjects of the artwork. A bear skull was placed on top of a large, flat rock in an area called the Skull Chamber. There is evidence a fire was lit before it was set there, raising the possibility that it had some kind of ritual function. More than 190 bear skulls have been found in the cave, giving paleontologists an enormous amount of information about a species that disappeared 20,000 to 25,000 years ago and used caves in ways that were similar to how humans used them. The bears organized the space within the cave by digging shallow depressions in the cave floor, possibly as sleeping areas. They also made their own marks on the cave walls by repeatedly raking their claws across the limestone, incising sets of four parallel lines. In some cases the paintings in Chauvet Cave are a kind of collaboration between humans and bears. Human artists incorporated claw marks into some of their paintings. In others, cave bears made their marks on top of the paintings, adding a new element to the images that cave art expert Jean Clottes calls "the magic of the bears."

Chauvet Cave Paintings 10,000 Years Older than Previously Thought

Radiocarbon dating in the Chauvet Cave in the mid 2010s revealed a new chronology of human and animal occupation of the site during the Paleolithic era. Léa Surugue wrote in the International Business Times: Previous analyses had dated the charcoal drawings back to 22,000–18,000 BP. However, the comprehensive dating program carried out in the cave now indicates a much older age (32,000–30,000 BP) for the black drawings, which are the only one in the cave datable with the radiocarbon-dating method. All the results are published in the Proceedings of the National [Source: Léa Surugue, International Business Times, April 11, 2016]

“According to analysis of the absolute dates obtained from the artworks, as well as other data derived from traces of animal and human activity, the cave went through two distinct periods of human occupation: one from 37 to 33,500 years ago, and the other from 31 to 28,000 years ago. Additionally, the scientists found bears also took refuge in the cave until 33,000 years ago.

“It is the first time that scientists are able to come up with a chronology of the cave's occupation using time references that everyone can understand. "Before 2009, we were not able to date human occupation in the cave precisely, because we did not know how to convert a given measurement of radiocarbon in a sample into an estimate of the sample's calendar age. This study is the first to date human and animal occupation of the Chauvet cave into actual calendar years," study author Anita Quiles, from the French Institute for Eastern Archaeology, told IBTimes UK.

“In total, Quiles and her team analysed 250 radiocarbon dates, collected over 15 years. They include analyses of black animal drawings and charcoal marks (including torch marks), but also charcoal and bear bones found on the cave's floor. Although not all the artworks in the cave have been analysed, radiocarbon dating from the black charcoal drawings reveal that most were probably created during the first phase of human occupation, between 37,000 to 33,500 years ago. These findings challenge traditional beliefs about parietal art. Indeed, experts were surprised that our human ancestors were able to create such rich and detailed frescoes, so far back in the past. "Now, we understand that even at this time, humans were capable of creating such magnificent and elaborate artworks. The drawings are full of dynamism, they reflect a real desire to transmit something to an audience," Quiles says.

“The study of the bears' bones samples suggests an overlap between their occupation of the cave and that of the first humans who passed through Chauvet. However, the probability that they crossed paths is low, because ancient humans would probably not have entered the territory of such a dangerous animal. Dating conducted in the cave does not allow researchers to know how long the humans used the cave for, but it is also probable that they did not use it continuously during their first and second phase of occupation.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024