Home | Category: First Modern Human Art and Culture

EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART

It has been said that the greatest innovation in modern humans was not tools or weapons but art and symbolic expressions that are associated with it. Around 40,000 years ago a "cultural explosion" began in Europe that would eventually yield magnificent cave paintings, detailed sculptures, elaborate body ornamentation and musical instruments. Before that time the only things that made by ancient men that qualified as art were carefully-crafted stone tools, etched rocks and minerals and perforated shells and beads. The first evidence of painting — perhaps dating as far back as 55,000 years ago — is from Australia of all places. Two Paleolithic harpoons, at least 60,000 years old, decorated with geometric figures discovered at Veyrier near Geneva, were once declared the world's oldest examples of art. But many other pieces have since had similar pronouncements made about them.

Jonathan Jones wrote in The Guardian: “A century ago, cave art was still barely accepted as being genuine. When Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola claimed in 1880 that paintings in Altamira cave in Spain were prehistoric, he was mocked and reviled as a faker. Gradually their antiquity was recognised but it was only when tremendous depictions of animals were found at Lascaux in France in 1940 that cave art exploded into modern culture. Today, it is at the heart of thinking about human evolution because it seems to illuminate the birth of the complex cathedral of the modern mind. [Source: Jonathan Jones, The Guardian February 23, 2018]

The caves where the paintings are found are very dark. Deep inside them the darkness is absolute. Without a light source you can't see your hand in front or face. Lighting in prehistoric times was provided by torches and animal fat lamps. Some of the caves are very wet: quiet and still except the sound of dripping water.

Jean Clottes, a French art historian and archaeologist, is regarded as the grand old man of cave art. He studied archaeology while teaching high school English in Foix, a Pyrenees city in an area with a lot of decorated caves, and didn't earn his doctorate until he was 41. In the early 1970s he was the director of prehistory in the mid Pyrenees and was the one who got a first good look when a new discovery is made. In 1992, he was promoted to the rank of inspector general by the French Ministry of Culture after he stood by his claim that an art cave (Cosquer) was for real when everyone else said it was bogus — and he turned out to be right.

Websites and Resources on Prehistoric Art: Chauvet Cave Paintings archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet ; Cave of Lascaux archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en; Trust for African Rock Art (TARA) africanrockart.org; Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com; Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology, by Peter Brown peterbrown-palaeoanthropology.net ; Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RELATED ARTICLES:

WORLD'S EARLIEST ART factsanddetails.com ;

WHY EARLY HUMANS MADE ART factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

IMAGES IN EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART: ANIMALS, HAND PRINTS, FIGURES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL ART, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEARS OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

CAVE ART IN SPAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAVE ART IN FRANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LASCAUX CAVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CHAUVET CAVE: PAINTINGS, IMAGES, SPIRITUALITY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CHAUVET CAVE DISCOVERY, STUDY, FILMING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST SCULPTURES factsanddetails.com ;

VENUS STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008) Amazon.com;

“What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity” by Jean Clottes Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist Amazon.com;

“The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art” by Paul Bahn (2017) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art (World of Art)” (2017) by Bruno David Amazon.com;

“Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe” by Paul Bahn Amazon.com;

“Images of the Ice Age” by Paul G. Bahn Amazon.com;

“The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art” by David Lewis-Williams (2004) Amazon.com;

“Stepping-Stones: A Journey through the Ice Age Caves of the Dordogne” by Christine Desdemaines-Hugon (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs” by Mario Ruspoli (1987) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave” by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps (1996) Amazon.com;

“Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times” by Jean Clottes (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Altamira” by Matilde Muzquiz Perez-Seoane, Frederico Bernaldo de Quiros (1999) Amazon.com;

Types of Cave Art

The cave art in Europe falls into three general categories: 1) enigmatic abstract marks such as dots and squiggles; 2) “human” hands; 3) lifelike portrayals of mammoths, horses, bison, lions and other animals.

Laura Anne Tedesco wrote for The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ Beginning around 40,000 B.C., the archaeological record shows that anatomically modern humans effectively replaced Neanderthals and remained the sole hominin inhabitants across continental Europe. At about the same time, and directly linked to this development, the earliest art was created. These initial creative achievements fall into one of two broad categories. Paintings and engravings found in caves along walls and ceilings are referred to as "parietal" art. [Source: Laura Anne Tedesco, Independent Scholar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2000]

The caves where paintings have been found are not likely to have served as shelter, but rather were visited for ceremonial purposes. The second category, "mobiliary" art, includes small portable sculpted objects which are typically found buried at habitation sites. In the painted caves of western Europe, namely in France and Spain, we witness the earliest unequivocal evidence of the human capacity to interpret and give meaning to our surroundings. Through these early achievements in representation and abstraction, we see a newfound mastery of the environment and a revolutionary accomplishment in the intellectual development of humankind.”

When and Where European Cave Paintings Were Made

Of the 200 or so caves, with about 15,000 paintings and engravings, about 90 percent are in France and Spain in three major clusters: 1) in the foothills of the central Pyrenees in France; 2) in the Cantabrian mountains along the Bay of Biscay coast in northern Spain (Altamira is here); and 3) within a 20 mile radius of the village Les Eyziers in southwestern France. Most of the caves with paintigs, including Lascaux, are in the Dordogne region in the French Pyrenees. There are around 60 caves in France and 30 Spain that have ancient wall paintings. The other 110 or so have engravings and markings.

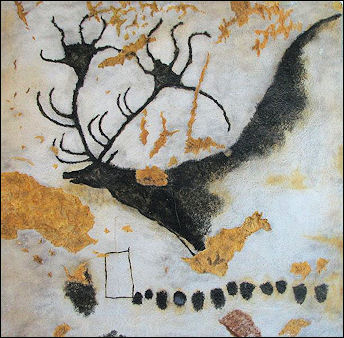

Megaloceros from Lascaux Cave Chip Walter wrote in National Geographic: “Most of the cave paintings in southern France and Spain were created after the Neanderthals disappeared. Why there? Why then? One clue is the caves themselves—deeper and more extensive than the ones in the Ach and Lone River Valleys of Germany or the rock shelters of Africa. Tito Bustillo in northern Spain is a half mile from one end to the other. El Castillo and other caves on Monte Castillo dive, twist, and turn into the ground like enormous corkscrews. France’s Lascaux, Grotte du Renne, and Chauvet run football fields deep into the rock, with multiple branches and cathedral-like chambers. [Source: Chip Walter, National Geographic, January 2015]

Michael Balter wrote in sciencemag.org:“Homo sapiens first colonized Europe from Africa around 40,000 years ago. But until the early 1990s, there was little firm evidence that our species engaged in sophisticated artistic activity that early. Many archaeologists assumed that modern humans developed their artistic skills only gradually, culminating in spectacular galleries like the 15,000-year-old painted caves at Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain. The discovery of Chauvet changed all that and convinced most researchers that early artists had brought their skills with them from Africa. [Source: Michael Balter, sciencemag.org, May. 14, 2012 ^=^]

“Yet for years Chauvet seemed to stand alone, leading some archaeologists to question whether its dating—based in large part on radiocarbon samples taken directly from its charcoal paintings—was correct. Nevertheless, evidence for other art of about the same age continued to accumulate. At Fumane Cave in Italy, for example, archaeologists found depictions of animals and what appeared to be a half-human, half-beast figure, dated to about 37,000 years ago or even older, although the error ranges for the dates were fairly wide.” ^=^

The age of cave art more less coincided with the last Ice Age and came to an end at the end of the Ice Age when the steppes that covered Europe — which supported large numbers of grazing animals — were replaced by forests. Archaeologists argue that the painting stopped when the large herds of steppe grazing animals disappeared and early modern humans started looking for other food source and their culture changed.

Aurignacians: Producers of Europe's First Great Art?

The Aurignacian (42,000 to 28,000 years ago), Gravettian (28,000 to 22,000 years ago), Solutrean (22,000 to 18,000 years ago) and Magdalenian (18,000 to 10,000 years ago) cultures are all named French sites. Each site has art, tools, weapons and adornment associated with it.

The Aurignacian people is the name given to the early modern humans that created Europe's first art works. On their skill the German film director Werner Herzog said: “We should never forget the dexterity of these people. They were capable of creating a flute. It is a high-tech procedure to carve a piece of mammoth ivory and split it in half without breaking it, hollow it out, and realign the halves.

“We have one indicator of how well their clothing was made. In a cave in the Pyrenees, there is a handprint of a child maybe four or five years old. The hand was apparently held by his mother or father, and ocher was spit against it to get the contours and you see part of the wrist and the contours of a sleeve. The sleeve is as precise as the cuffs of your shirt. The precision of the sleeve is stunning.

“Aurignacian people that lived in Europe between 37,000 and 28,000 years ago have been divided into three subcultures based on the ornaments they wore: usually teeth, bones or and shells with a hole or a groove to accommodate a chords. A group that lived in present-day Germany and Belgium preferred perforated teeth and disk-shaped ivory beads. In Austria, southeast France, Greece and Italy they preferred shell. A third group lived in Spain and southern and western France.”

Neanderthals – Not Modern Humans – Were the First Artists?

The earliest cave painting discovered so far, found at 11 locations in northern Spain, including the UNESCO world heritage sites of Altamira, El Castillo and Tito Bustillo, were made by Neanderthals. [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, November 15, 2012 |=|]

Neanderthals made cave painting in Spain 65,000 years ago — thousands of years before modern humans were even in Europe — scientists say. The finding debunks the widely-held belief that modern humans are the only species capable of producing art. Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “In caves separated by hundreds of miles, Neanderthals daubed, drew and spat paint on walls producing artworks, the researchers say, tens of thousands of years before modern humans reached the sites. The finding, described as a “major breakthrough in the field of human evolution” by an expert who was not involved in the research, makes the case for a radical retelling of the human story, in which the behaviour of modern humans differs from the Neanderthals by the narrowest of margins. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, February 22, 2018 |=| ]

“Until now, the evidence for Neanderthal art has been tenuous and hotly contested, often because the works were not old enough to rule out modern humans as the real artists. But the latest findings, based on new dates of symbols, hand stencils and geometric shapes found on cave walls across Spain, make the most convincing case yet. “I think we have the smoking gun,” said Alistair Pike, professor of archaeological sciences at the University of Southampton. “When we got the first date for the art, we were dumbfounded.” |=|

“In a study published in Science an international team led by researchers in the UK and Germany dated calcite crusts that had grown on top of ancient art works in three caves in Spain. Because the crusts formed after the paintings were made, the material gives a minimum age for the underlying art. Measurements from all three caves revealed that paintings on the walls predated the arrival of modern humans by at least 20,000 years.

“Historically, works of art and symbolic thinking have been held up as proof of the cognitive superiority of modern humans – examples of the exceptional skills that define our species. “To my mind this closes the debate on Neanderthals,” said João Zilhão, a researcher on the team at the University of Barcelona. “They are part of our family, they are ancestors, they were not cognitively distinct, or less endowed in terms of smarts. They are just a variant of humankind that as such exists no more.” |=|

See Separate Articles: NEANDERTHAL ART, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEAR OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com

Neanderthal Art Works

The four caves in Spain with Neanderthal art are: 1) La Pasiega: with a red ladder shape, at least 64,800 years old; 2) Ardales: with painted rock ‘curtains’, at least 65,500 years old; 3) Maltravieso: with hand stencils, at least 66,700 years old; 4) Aviones: with painted seashells dated to 115,000 years ago. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, February 22, 2018 |=| ]

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “At La Pasiega cave near Bilbao in the north, a striking ladder-like painting has been dated to more than 64,800 years old. Faint paintings of animals sit between the “rungs”, but these may have been added when Homo sapiens found the caves millennia later.

“In Maltravieso cave in western Spain, a hand shape – thought to have been created by spraying paint from the mouth over a hand pressed to the cave wall – was found to be at least 66,700 years old. At the Ardales cave near Malaga, stalagmites and stalactites that form curtain-like patterns on the walls appear to have been painted red, and have been dated to 65,500 years ago. What the creators sought to express with their efforts is anyone’s guess. “We have no idea what any of it means,” said Dirk Hoffmann at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. |=|

“It is not the only question left unanswered. “It’s fascinating to demonstrate that the Neanderthals were the world’s first artists, and not our own species,” said Paul Pettit, professor of palaeolithic archaeology at Durham University. “The most important question still remains, however. What were Neanderthals doing in the depths of dark and dangerous caves if it wasn’t ritual, and what does that imply?” |=|

“In a second paper, published in Science Advances, Hoffman and others show that dyed and decorated seashells found in the Aviones sea cave in southeast Spain were made by Neanderthals 115,000 years ago, pointing to a long artistic tradition. |=|

Why Was Cave Art Produced

No one is sure why these caving paintings were made. Many of the them were — and still are — extremely difficult to get to and they were not lit with electricity as they are today. For these reason many archaeologist speculate they fulfilled some kind of ritualistic, ceremonial or religious function. They may have even been built to honor gods but it difficult to say for sure.

Chip Walter wrote in National Geographic: “But most of the cave paintings in southern France and Spain were created after the Neanderthals disappeared. Why there? Why then? One clue is the caves themselves—deeper and more extensive than the ones in the Ach and Lone River Valleys of Germany or the rock shelters of Africa. Tito Bustillo in northern Spain is a half mile from one end to the other. El Castillo and other caves on Monte Castillo dive, twist, and turn into the ground like enormous corkscrews. France’s Lascaux, Grotte du Renne, and Chauvet run football fields deep into the rock, with multiple branches and cathedral-like chambers. [Source: Chip Walter, National Geographic, January 2015]

“Perhaps the explosion of creativity we see on the walls of these caverns was inspired in part by their sheer depth and darkness—or rather, the interplay of light and dark. Illuminated by the flickering light from fires or stone lamps burning animal grease, such as the lamps found in Lascaux, the bumps and crevices in the rock walls might suggest natural shapes, the way passing clouds can to an imaginative child. In Altamira, in northern Spain, the painters responsible for the famous bison incorporated the humps and bulges of the rock to give their images more life and dimension. Chauvet features a panel of four horse heads drawn over subtle curves and folds in a wall of receding rock, accentuating the animals’ snouts and foreheads. Their appearance changes according to your perspective: One view presents perfect profiles, but from another angle the horses’ noses and necks seem to strain, as if they are running away from you. In a different chamber a rendering of cave lions seems to emerge from a cut in the wall, accentuating the hunch in one animal’s back and shoulders as it stalks its unseen prey. As our guide put it, it is almost as if some animals were already in the rock, waiting to be revealed by the artist’s charcoal and paint.

See Separate Article: WHY EARLY HUMANS MADE ART europe.factsanddetails.com

Cave Art Images

The images found in cave art are mainly of animals that early man hunted, some of them have lines marked on their flanks that perhaps are spears use to kill them. In Lascaux there is a famous depiction of a partially-disemboweled bison. There are not many images of reindeer even though they were a primary food source. Bears also don't show up much. Some art historians and archaeologists suggest this is because maybe they were ritual, totemic species and rendering them in a cave was inauspicious.

Some of the more interesting images and caves include a frieze of pregnant fat women holding a bison horn found in a subterranean tunnel near Beune, France; a 20 foot-long painting in a the Niaux cave near Toulous that could only reached by swimming over a mile in an underground cave; a painting a figure with a bearded human face, antlers, the eyes of an owl, the tail of a horse and the claws of lion, believed to be a representation of a prehistoric shaman, found near Les Trois Fréres, a French town in the foothills of the Pyrenees. [ World Religions edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

See Separate Article: IMAGES IN EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART: europe.factsanddetails.com

Cave Art in France

There are 120 prehistoric caves in France. Only 23 are open to the public. Seventy of these caves are in the Niaux cave complex (55 miles south of Toulouse) in the Pyrenees. Two thirds of the of all the know prehistoric artworks was produced in Perigord. The Dordogne region and the Dordogne River are in Perigord, a rural area famous for foie gras and truffles and medieval villages. Many of the caves are operated by the French Ministry of Culture. Those that are open to the public are carefully regulated. The visits are kept brief and are strictly controlled to protect the art.

Les Trois Frères (30 miles northwest of Niaux) contains spectacular drawings, including the famous "sorcerer," a man with owl eyes, wizard beard, horse's tail, handlike paws, antlers headgear and a reindeer skin. In 1912, three boys exploring an area where the Volp River went underground between Enterre and le Tuc d'Audooubert in the Pyrenean foothills discovered Les Trois Frères caves. In addition to the paintings the boys found fantastic sculptures of bison.

Cave art sites in southern France and northern Spain

Other caves of note include La Magdalaine Cave, with images made between 15,000 B.C. and 10,000 B.C., including a nude woman; and Cougnac Cave, with an impressive red ibex. Peche Merle features a line of lines of red dots lead to a decorated chamber with huge red fish (a pike) in the body of one horse, horses with human hand prints, Another chamber has eight abstract female and mammoth images. Font-de-Gaume Cave (near Eyzies-de-tayac) contain 15,000-year-old paintings and engravings, including one of a little horse.

See Separate Article: EARLY CAVE ART IN FRANCE europe.factsanddetails.com

Cave Art in Spain

Miranda S. Spivack wrote in the Washington Post: “For aficionados of early human art like my husband and me, Spain may be the best destination in Europe (some say the world) to see all kinds of prehistoric art, up close. Spain’s sites, scattered throughout the country, include dozens of dimly lit caves like this one as well as hundreds of “abrigos,” or outdoor overhangs, where the images are still very bright. “If you are interested in the very origins of artistic expression, this is where you need to be,” said Ian Tattersall, a specialist in Spanish cave art and a former curator at New York’s American Museum of Natural History. “What is really cool about many of the Spanish caves is the fact that they cover a period of cave art not very common in France,” although that is where their name comes from. That would be the Solutrean period of more than 20,000 years ago, Tattersall said. [Source: Miranda S. Spivack, Washington Post, October 30, 2014 ^||^]

“The oldest cave art in the world is thought to be in El Castillo, a popular Spanish cave an hour’s drive away near the town of Puente Viesgo, where there are outlines of human hands as well as images of animals. The cave artists only occasionally drew human forms. Those are often simpler than the animal portraits: stick figures, mysterious symbols that may denote fertility. Or not. “There is always an explanation du jour, and everybody has their own pet theory about this stuff,” Tattersall said. “It does beg to be explained, but we only know that these deep cave sites that are decorated were very special and meaningful places to the people who made them.”^||^

“Sometimes the artists were remarkably sophisticated, such as in Covalanas, in the Cantabrian region, where the artist was able to incorporate the curve of the stone to make it seem that the animals were running. These works combine sculpture and painting, alongside hand prints and dots.” ^||^

See Separate Article: CAVE ART IN SPAIN europe.factsanddetails.com

Pettakere Cave in Sulawesi

40,000 Year Old Cave Art Found in Sulawesi and Borneo, Indonesia

Remains at Niah Cave show that men have been living on Borneo for a long time. In the karst interior of Borneo are networks of caves with rock art and hand prints, some of them dated to 12,000 years ago. More significantly, rock art and hand prints found in caves in Sulawesi have been dated to nearly 40,000 years ago. Deborah Netburn wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Archaeologists working in Indonesia say prehistoric hand stencils and intricately rendered images of primitive animals were created nearly 40,000 years ago. These images, discovered in limestone caves on the island of Sulawesi just east of Borneo, are about the same age as the earliest known art found in the caves of northern Spain and southern France. The findings were published in the journal Nature. "We now have 40,000-year-old rock art in Spain and Sulawesi," said Adam Brumm, a research fellow at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and one of the lead authors of the study. "We anticipate future rock art dating will join these two widely separated dots with similarly aged, if not earlier, art." [Source: Deborah Netburn, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2014 ~\~]

“The ancient Indonesian art was first reported by Dutch archaeologists in the 1950s but had never been dated until now. For decades researchers thought that the cave art was made during the pre-Neolithic period, about 10,000 years ago. "I can say that it was a great — and very nice — surprise to read their findings," said Wil Roebroeks, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the study. "'Wow!' was my initial reaction to the paper." ~\~

The researchers said they had no preconceived ideas of how old the rock art was when they started on this project about three years ago. They just wanted to know the date for sure. To do that, the team relied on a relatively new technique called U-series dating, which was also used to establish minimum dates of rock art in Western Europe. We have seen a lot of surprises in paleoanthropology over the last 10 years, but this one is among my favorites. - Wil Roebroeks, Leiden University archaeologist

First they scoured the caves for images that had small cauliflower-like growths covering them — eventually finding 14 suitable works, including 12 hand stencils and two figurative drawings. The small white growths they were looking for are known as cave popcorn, and they are made of mineral deposits that get left in the wake of thin streams of calcium-carbonate-saturated water that run down the walls of a cave. These deposits also have small traces of uranium in them, which decays over time to a daughter product called thorium at a known rate. "The ratio between the two elements acts as a kind of geological clock to date the formation of the calcium carbonate deposits," explained Maxime Aubert of the University of Wollongong in Australia's New South Wales state, the team's dating expert. ~\~

“Using a rotary tool with a diamond blade, Aubert cut into the cave popcorn and extracted small samples that included some of the pigment of the art. The pigment layer of the sample would be at least as old as the first layer of mineral deposit that grew on top of it. Using this method, the researchers determined that one of the hand stencils they sampled was made at least 39,900 years ago and that a painting of an animal known as a pig deer was at least 35,400 years old. In Europe, the oldest known cave painting was of a red disk found in a cave in El Castillo, Spain, that has a minimum age of 40,800 years. The earliest figurative painting, of a rhinoceros, was found in the Chauvet Cave in France; it goes back 38,827 years. ~\~

“The unexpected age of the Indonesian paintings suggests two potential narratives of how humans came to be making art at roughly the same time in these disparate parts of the world, the authors write. It is possible that the urge to make art arose simultaneously but independently among the people who colonized these two regions. Perhaps more intriguing, however, is the possibility that art was already part of an even earlier prehistoric human culture that these two groups brought with them as they migrated to new lands. One narrative the study clearly contradicts: That tens of thousands of years ago prehistoric humans were making art in Europe and nowhere else "The old 'Europe, the birthplace of art' story was a naive one, anyway," said Roebroeks. "We have seen a lot of surprises in paleoanthropology over the last 10 years, but this one is among my favorites." ~\~

In 2018, Borneo was added to a growing list of places with some very old cave art sites. National Geographic reported: Countless caves perch atop the steep-sided mountains of East Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo. Draped in stone sheets and spindles, these natural limestone cathedrals showcase geology at its best. But tucked within the outcrops is something even more spectacular: a vast and ancient gallery of cave art. Hundreds of hands wave in outline from the ceilings, fingers outstretched inside bursts of red-orange paint. Now, updated analysis of the cave walls suggests that these images stand among the earliest traces of human creativity, dating back between 52,000 and 40,000 years ago. That makes the cave art tens of thousands of years older than previously thought. [Source: Maya Wei-haas, National Geographic, November 7, 2018]

See Separate Articles: EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

200,000-Year-Old Handprints from Tibet — the World’s Earliest Cave Art?

Fossilized children's handprints and footprints found near a hot spring in Tibet could be 200,000 years old, according to one study, making them the oldest cave art ever found. The prints were made in travertine stone which is soft when it's wet and hardens when it dries. There is a debate among archaeologists as to whether the handprints are really art and whether they are as old as claimed. A study on the prints was published September 2021 in the journal Science Bulletin. “The question is: What does this mean? How do we interpret these prints? They’re clearly not accidentally placed,” study co-author Thomas Urban, a scientist at Cornell University’s Tree-Ring Laboratory, said. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, February 3, 2024; Isis Davis-Marks, Smithsonian magazine, September 17, 2021

Isis Davis-Marks wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Between 169,000 and 226,000 years ago, two children in what is now Quesang, Tibet, left a set of handprints and footprints on a travertine boulder. Seemingly placed intentionally, the now-fossilized impressions may be the world’s oldest known parietal, or cave, art. The prints were dated using the uranium series method. The ten impressions—five handprints and five footprints—are three to four times older than comparable cave paintings in Indonesia, France and Spain. Given their size and estimated age, the impressions were probably left by members by the genus Homo. The individuals may have been Neanderthals or Denisovans rather than Homo sapiens.

The discovery offers the earliest evidence of hominins’ presence on the Tibetan Plateau and supports previous research indicating that children were some of the first artists. Researchers discovered the hand and footprints — believed to belong to a 12-year-old and 7-year-old — near the Quesang Hot Spring in 2018. Though parietal art typically appears on cave walls, examples have also been found on the ground of caverns. “How footprints are made during normal activity such as walking, running, jumping is well understood, including things like slippage,” Urban told “These prints, however, are more carefully made and have a specific arrangement—think more along the lines [of] how a child presses their handprint into fresh cement.”

Do the Tibetan prints constitute art? Matthew Bennett, a geologist at Bournemouth University who specializes in ancient footprints and trackways, told Gizmodo that the impressions’ placement appears intentional: “It the composition, which is deliberate, the fact the traces were not made by normal locomotion, and the care taken so that one trace does not overlap the next, all of which shows deliberate care.” Other experts don’t necessarily buy into this. “I find it difficult to think that there is an ‘intentionality’ in this design,” Eduardo Mayoral, a paleontologist at the University of Huelva in Spain told NBC News.“And I don’t think there are scientific criteria to prove it—it is a question of faith, and of wanting to see things in one way or another.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024