Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE

While the Greeks made sculptures of idealized human forms, the Roman tended to make portraits. Romans made sculptures of gods, heroes, emperors, generals and politicians. They also used sculpted images to adorn the capitals of columns and the helmets of gladiators. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Roman sculptures often reflected the fashions and lifestyles that were prevalent when they were made. Archaeologists can even date sculptures of Roman by their hairdos and clothing styles. During the Augustan Age, for example, women parted their hair in the middle with a central roll. The Flauvians and Antiones had more elaborate coiffures that resembled a honeycomb of curls. Sculpture were made spectacular-looking but hard to work stone such as porphyry from Gebel Dokhan in northeast Egypt, basanite granite from Gebel Fatireh in eastern Egypt, and blue, yellow, green, black and grey marble from elsewhere in the empire.

Roman sculpture has its roots in the sculpture of the Etruscans, who preceded the Romans and flourished in central Italy between the the 8th and 3rd centuries B.C. Philip M. Soergel wrote: Etruria was an important export market for Greek vases, and Greek artisans worked in its cities for Etruscan patrons. One such colony of Greek craftsmen existed in Caere (modern Cerveteri, north of Rome), where there is still a large Etruscan necropolis. Rome's last three kings were Etruscan; the last of them, Tarquin the Proud, who was expelled in 510 B.C., built a great temple for the triad of gods, Jupiter, Minerva, and Juno on the Capitoline Hill in Etruscan style. As a model for all future Roman temples, it stood on a raised podium and was decorated with painted terracotta moldings. The cult statue of Jupiter was made of terracotta by an Etruscan sculptor from Veii named Vulca. A surviving terracotta statue from the school of Vulca was found in the ruins of Veii and now stands in the Villa Giulia museum in Rome. The so-called Apollo of Veii originally looked down from the ridgepole of an Etruscan temple. It has the "archaic smile" of the Greek kouroi (nude male statues). [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

Etruscan influence continued in Rome after the Etruscan kings were driven out, and Etruscan sculptors continued to work there. One monument that survived from this early period is a bronze she-wolf of about 500 B.C. In the Renaissance period, two infants were added, suckling her teats. The addition clearly identified this wolf with the legendary wolf that suckled Rome's legendary founders, Romulus and Remus, as infants, but it is not clear whether the original statue should be connected with the legend or not. The Etruscan influence on Rome faded, however, as Rome's conquests brought Greece into the empire.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FAMOUS PIECES OF ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MOSAICS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMANS CRAFTS: POTTERY, STUFF IN THE SECRET CABINET factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN GLASS europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN PAINTING: HISTORY, FRESCOES, TOMBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Sculpture” by Diana E. E. Kleiner (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Roman Sculpture” (Reprint) by Elise A Friedland, Melanie Grunow Sobocinski, Elaine Gazda Amazon.com;

“Statues in Roman Society: Representation and Response” by Peter Stewart Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Sculpture: An Image Archive for Artists and Designers” by Kale James Amazon.com;

“The Meroë Head of Augustus” (Object in Focus) by Thorsten Opper (2014) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“The Interpretation of Architectural Sculpture in Greece and Rome” by Diana Buitron-Oliver (1997) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic and Roman Ideal Sculpture: The Allure of the Classical” by Rachel Meredith Kousser Amazon.com;

“Roman Sculpture in Context” by Peter D de Staebler, Anne Hrychuk Kontokosta (2021) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Ancient Sculpture, Egyptian – Assyrian – Greek – Roman: With One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations” by George Redford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques” by Janet Grossman (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Phantom Image: Seeing the Dead in Ancient Rome” by Patrick R. Crowley (2019) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection” by Lisa Ayla Cakmak, Katharine A Raff, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“Roman Portraits: Sculptures in Stone and Bronze in the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art” by Paul Zanker (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Nude: Heroic Portrait Statuary 200 BC - AD 300" by Christopher H. Hallett Amazon.com;

“Sex on Show: Seeing the Erotic in Greece and Rome” by Caroline Vout (2013) Amazon.com;

“Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture” by Marilyn B. Skinner Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Michael Siebler and Norbert Wolf (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Empire: 100-450 AD (Oxford History of Art) by Jaś Elsner Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Paul Zanker (2012) Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Fred Kleiner Amazon.com;

“Art & Archaeology of the Roman World” by Mark Fullerton (2020) Amazon.com

“The Language of Images in Roman Art” by Tonio Hölscher (2004) Amazon.com;

“Power of Images in the Age of Augustus” by Paul Zanker and Alan Shapiro (1988) Amazon.com

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Tradition in Art” by Michael Greenhalgh, (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greece and Rome, From the Rise of Greece to the Fall of Rome”

by Giovanni Becatti (1967) Amazon.com;

History of Ancient Roman Sculpture

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: Large polychrome terra-cotta images, such as the Apollo of Veii (Villa Giulia, Rome), sandstone tomb effigies, and tomb paintings reveal a native feeling for voluminous forms and bold decorative color effects and an exuberant, vital spirit. From c.400 B.C. through the Hellenistic age, the vitality of the archaic period gave way to imitation of the Greek classical models combined with a native trend toward naturalism (Mars of Todi, Vatican). The merging of these trends produced the establishment of Hellenistic realism in Roman Italy at the end of the republic and the beginning of the empire (Orator, Museo Archeologico, Florence; Capitoline Brutus, Conservatori, Rome.). [Source: The Columbia Encyclopedia]

By the time of the empire, the Roman conception of art had become allied with the political ideal of service to the state. In the Augustan period (30 B.C.–AD 14) there was an attempt to combine realism with the Greek feeling for idealization and abstract harmony of forms. This modification is seen in the famous Augustus from Prima Porta (Vatican), which represents the first of a long series of the distinctly Roman type of portrait. Under the emperors from Tiberius through the Flavians ( A.D. 14–AD 96) portrait busts reveal in general a growing concern with effects of pictorial refinement and psychological penetration. The magnificent reliefs from the Arch of Titus, Rome, commemorating the conquest of Jerusalem in AD 70, mark a climax in the development of illusionism in historical relief sculpture.

From the time of Trajan ( A.D. 98–AD 117) the influence of the art of the Eastern provinces began to gain in importance. The spiral band of low reliefs on Trajan's Column (Rome), commemorating the wars against the Daci, employs a system of continuous narration. In the period of Hadrian (117–138) there was a reversion to the idealization of the Augustan style and at the same time a growing sense of voluptuousness. Major works from the later period of the Antonines (138–192) are the column and the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius (Rome).

From the time of Caracalla to the death of Constantine I (211–337) the rapid assimilation of Eastern influences encouraged a tendency toward abstraction that later developed into the stiff iconographic forms of the early Christian and Byzantine eras. The reliefs of the friezes from the Arch of Constantine, Rome (c.315), may be regarded as the last example of monumental Roman sculpture.

Greek and Roman Sculpture

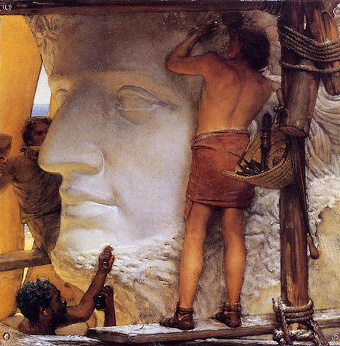

In 211 B.C. during the Punic Wars, the city of Syracuse in Sicily, fell to the Romans. Syracuse was a great Greek city filled with works of art, and much of it made its back to Rome as spoils of war. Philip M. Soergel wrote: They made a strong impression on the Roman elite, who clamored for more Greek art. In the second century B.C., when Rome conquered Greece, there was ample opportunity for more looting. In 146 B.C. Rome destroyed Corinth, and the commander, Lucius Mummius, sent shiploads of art works to Rome. A flourishing industry arose in Greece of copying sculptures in marble for the Roman market. The skill of the copyists varied, and though the sculptors knew how to make exact replicas, it is clear that they sometimes varied the originals. Yet without these Roman copies modern understanding of Greek sculpture would be greatly diminished. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

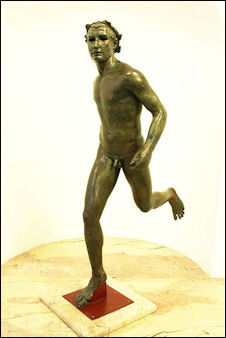

Greek statue of a runner After emperor Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) solidified control over what would become the Roman Empire was determined to give the empire a capital worthy of its position as master of the Mediterranean world. Philip M. Soergel wrote: After He turned to the art of classical Greece to accomplish this goal. His artists revived the Canon of Polyclitus, a classical treatise on the proper proportions for sculpture, in creating statues of Augustus. Indeed, a comparison between the so-called "Prima Porta" statue of Augustus, found at the villa of his wife Livia a short distance north of Rome, with the Doryphoros (Spearbearer) of the great Roman sculptor Polyclitus reveals some startling similarities. The statues have the same tilt of the head, and the same treatment of the hair. While Augustus has some individual features, such as his high cheekbones and the hint of resolution to his brow, his physique adheres to the proportions which Polyclitus set forth in his Canon.

Roman sculpture regressed from Greek sculpture back to images that seemed rigid and frozen in space. Romans liked to put copies of Greek sculptures in their gardens and homes as decorations and works of art. Historian Daniel Boorstin wrote in “The Creators”, “While the Greeks gave their gods and ideal humans form the Romans attempted to make their ruler godlike." The Romans also recognized the need to humanize their subjects, and thus Nero was given same baby fat and Hadrian was made majestic. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

The main difference between Greek and Roman sculpture was the later was more personalized. Greeks statues were of idealized human forms of athletes and gods while Roman statues depicted real people — primarily people important enough to have an image of them commissioned, or wealthy enough to afford their own, There are few examples or ordinary people. All Roman emperors had their statues publicly displayed and statues of Marcus Aurelius, Caesar, and Vespasian all exist today. These statues obviously were intended to portray the leaders in the best light and ended up looking like the equivalent of modern-day blown dry images of politicians. The most revealing and skilled works are busts done of ordinary Romans and Arabs, but even their facial features and wrinkles were often used covey the intent of the sculptor not necessarily depict a real life person. [Source: “History of Art” by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

Sculpture, Death and Immortality in Ancient Rome

When the leader of the household died, a waxen image was made of his head and placed in a shrine on the family altar. During funerals these images were pulled out and carried in a procession. Later they were sculpted from marble because the wax only lasted for a few decades. [Source: "History of Art" by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

"Is there anyone," Polybius (205-125 B.C.) wrote, "who would not be edified by seeing these portraits of men reknown for their excellence and by having them all present as if they were living and breathing? Is there anything which is more ennobling than this?...thereby not allowing human appearances to be forgotten nor the dust of ages to prevail against men." ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

After a funeral, the family of the deceased nobleman painted a wax death mask of the nobleman on a bust which in turn was placed in the most prominent place in the house. Later on the bust was placed on a shelf in the atrium with likenesses of other deceased relatives, all of whom were connected by colored lines that assembled them into a genealogical chart. During some festivals a crown of bay leaves was placed on the bust and during family funerals people wore the masks during the procession.

Roman statues of runners

found at HerculaneumThe intent of Roman sculpture was to immortalize the people who were sculpted and artists attempted to capture a likeness of the individual. Greek sculpture on the other hand were of idealized humans. The masks of Roman actors were made to look like the people the actors were playing.

Destroying a statue carried the same meaning as destroying the existence of a person. "If statues could perpetuate memory," Boorstin wrote, “destroying them could erase memory...In addition to execution and confiscation of property the [name] of the condemned could not be perpetuated in his family, images of him were to be destroyed, and his name was supposed to be erased from all inscriptions. the only way the accused could escape these indignities was by committing suicide before the charges were officially lodged." The wife of condemned emperor had a sculpture secretly made after his death. To accomplish this the sculptures had to reassemble the emperor's dismembered body."

Ancient Roman Reliefs

Coins were a kind of small bas-relief. We get a sense of what many famous Romans looked like by their portrait on coins. Roman coins have been found all over Asia and ancient Chinese coins have been found in Rome. On a larger scale was the Column of Trajan (at Fori Imperiali), a 125-five-foot structure with a spiraling scene from Dacian Wars in the Balkans that if unwound would be 656 feet long. Built and inscribed between A.D. 106-113, the column was once topped by a statue of an Trajan, whose ashes and those of his wife are buried underneath its base. Originally it was supposed to be topped by an eagle. The statue of Trajan was destroyed in the Middle Ages.

Philip M. Soergel wrote: In one category of relief sculpture, the Romans could claim a degree of originality: the relief that narrated an historical event. The Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum commemorates the suppression of the revolt in Judaea that broke out in 66 A.D. Titus, who took over command of the Roman forces in Judaea from his father Vespasian, captured Jerusalem and then returned to Rome with his spoils to celebrate a Roman Triumph. In the triumphal ceremony, the victorious general paraded his captives and his spoils through the streets of Rome, through the Roman Forum along the "Sacred Way" and up to the temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill where he laid down his command. Inside the arch there are two great panels which portray the triumph: one shows the exhibition of the spoils, which include the seven-branched candlestick from the Temple in Jerusalem, and the other shows Titus himself in his triumphal chariot. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

There are two other great monuments in Rome that use continuous narration: the columns of Trajan and of Marcus Aurelius. Trajan added Dacia (modern Rumania) to the empire, and his column shows the campaigns that he waged to conquer Dacia. The story unfolds in a spiral scroll that runs from the bottom to the top of the column, where there perched a statue of the emperor himself. The episodes run into each other without obvious breaks. The column of Marcus Aurelius takes its inspiration from the column of Trajan. The "continuous narrative" frieze spirals up the column, but there is less attention to the factual recording of details. The nature of Marcus Aurelius' campaigns may account for the difference. Trajan's military operations resulted in an addition to the empire, whereas Marcus Aurelius was fighting to hold back barbarian attacks across the Roman frontier. The emphasis of his relief sculpture is more on the hardships and cruelty of war.

See Separate Article: TRAJAN 'S CONQUEST OF THE DACIANS AND TRAJAN'S COLUMN europe.factsanddetails.com

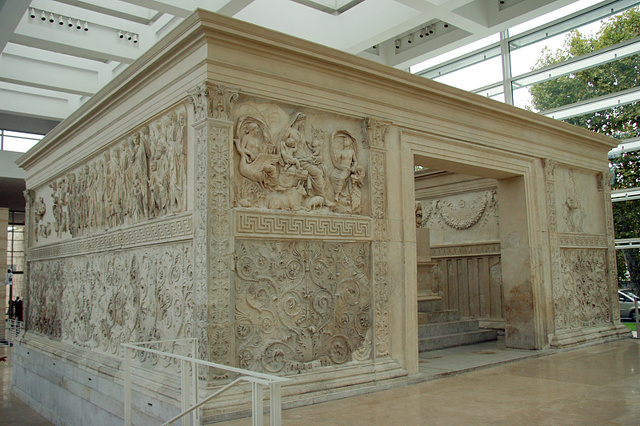

Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace")

The Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace") is an altar in Rome dedicated to the Pax Romana (early Roman Empire). Commissioned by the Roman Senate in 13 B.C. to honor the return of Augustus to Rome after three years of campaigning in Spain and Gaul (France) and consecrated in 9 B.C., it was originally located on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) in Rome in the the former flood plain of the Tiber River. Reflecting the Augustan vision of Roman civil religion, it features friezes that depict agricultural work meant to communicate the abundance and prosperity of the Roman Peace and reliefs that portray the sacrifice that took place at the ceremony for its dedication. As a whole the monument served both ritual and propaganda functions for Augustus. The reliefs are the most important features that survive of Augustan sculpture and one of the best examples of Roman sculpture as a whole.[Source Wikipedia]

The Ara Pacis is about the size of a small house and was aimed in part to reproduce the proportions of the Altar of the Twelve Gods which stood in the marketplace of Athens. Philip M. Soergel wrote: The panels on the north and south of the altar show a procession of the imperial family and court; the portraits are sufficiently realistic that most can be identified. On the east and west sides there are panels representing mythological scenes. One shows Aeneas, whom Augustus claimed as an ancestor, making sacrifice. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

The most arresting of all is a panel on the outside of the altar enclosure that shows a goddess holding two infants. Various fruits are on her lap, and a child offers her one in his small hand. At her feet a cow rests, and a sheep grazes. The identity of the goddess is unknown. Some scholars believe her to represent "Peace," while others claim she is "Mother Earth," or perhaps Venus, the mother of Aeneas and hence the progenitor of the Julian family. Whatever her identity, she adheres to the artistic traditions of classical Greece. Her stola, the proper dress of a Roman matron, clings to her body, revealing her breasts and even her navel underneath. It reproduces the transparent drapery of Greek sculpture of the 420s B.C., such as the Flying Victory of Painonius of Mende, except that in the Ara Pacis relief there is no wind. Yet the message is clear enough. The goddess, whoever she is, is bringing the fruits of peace, and of law and order, to the Roman Empire. This, proclaims the relief, was the achievement of Caesar Augustus.

The Ara Pacis were found in the early sixteenth century under silt from Tiber River floods. According to Archaeology magazine: it was reassembled as pieces resurfaced until it was nearly completed in 1938. Since then, scholars have examined the altar’s heavily decorated exterior, attempting to identify the mythological and historical figures represented. However, until several years ago when archaeologist Giulia Caneva of the University of Rome was asked whether the plants and flowers represented on the Ara Pacis were faithful representations or purely fantastical — and if she could identify them — no one had carefully studied the monument’s vegetation in such detail. “Soon Caneva discovered that the flowers were both fantasies and what she calls “extremely realistic” representations. The most surprising faithfully depicted species were two types of orchids, both of which are native to the Mediterranean. Until Caneva’s research, orchids were unknown in ancient art and had only been identified on works dating from the Renaissance and later. Caneva is continuing to decode the altar’s highly symbolic language of flowers and vegetation, which is part of the political message of this enduring monument to Augustus’ lineage and power. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

Aphrodisias Sculpting School and Mass Produced Sculptures

Aphrodisias (a two or three hour drive from Pamukkale and Ephesus) in Turkey was an ancient city dedicated to Aphrodite, goddess of love and fertility and the home of a famous sculpture school.. It rose to prominence in 88 B.C. and reached its peak as a Roman city during the first and second centuries Greeks arrived in the 6th century B.C. and the Romans took it over in the 1st century B.C. and it thrived as a religious and cultural center and tax-free trading haven. Around the 5th century it became the Byzantine city of Stavropolis. [Archeology Magazine January/February 1990; Dora Jane Hamblin, Smithsonian, Kena T. Erim, National Geographic, June 1972].

The Aphrodisias Sculpting School was one of the most famous sculpting school in antiquity. The Aphrodisias sculpting school thrived for 600 years, and the high-quality marble for the sculptures was found in abundance in quarries only a few miles away. The sculptors, some scholars claim, were the world's the first true artists, meaning they didn't just copy other statues like many Greek and Roman sculptors; instead they made unique creations. held up balconies and stairs.

Among the treasures unearthed there are a lion and snake mosaic and an impressive array of statues of figures from Greco-Roman mythology, centaurs, Trojan heroes and Roman emperors. There is so much stuff that expressions like an “an embarrassment of riches” has used to describe the trove, which far exceeds what the museum can hold. Among the provocative pieces preserved today are statues of Aphrodite cradling a child like a loving mother; Hercules rippling his muscles; and a woman weeping, which symbolized the subjugation of the city by Rome. Any rich noblemen who donated money to the school was honored with a statue, and there are plenty of these, as well as some magnificent friezes and sarcophagi, in the museum.

Many Greco-Roman sculptures that were thought to be masterpieces it turns were actually massed produced using assembly line methods for gardens. It was originally thought that large statues were made in a single piece but later it was discovered that they made from pre-caste parts joined together. Evidence that was so includes X-ray photographs that show details on how early statue parts were joined and flaws were hammered out; chemical analysis indicated that lead was added to save money on bronze. A 1,500-year-old earthenware vase that was one thought showed of human dismemberment actually depicted an ancient bronze statue assembly line.

Contexts for the Display of Ancient Roman Statues

“According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the early Roman Republic, the principal types of statue display were divinities enshrined in temples and other images of gods taken as spoils of war from the neighboring communities that Rome fought in battle. The latter were exhibited in public spaces alongside commemorative portraits. Roman portraiture yielded two major sculptural innovations: "verism" and the portrait bust. Both probably had their origins in the funerary practices of the Roman nobility, who displayed death masks of their ancestors at home in their atria and paraded them through the city on holidays. Initially, only elected officials and former elected officials were allowed the honor of having their portrait statues occupy public spaces. [Source: Marden Nichols, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

As is clear from many of the inscriptions accompanying portrait statues, which assert that they should be erected in prominent places, location was of crucial importance. Civic buildings such as council houses and public libraries were enviable locations for display. Statues of the most esteemed individuals were on view by the rostra or speaker's platform in the Roman Forum. In addition to contemporary statesmen, the subjects of Roman portraiture also included great men of the past, philosophers and writers, and mythological figures associated with particular sites.”

““Beginning in the third century B.C., victorious Roman generals during the conquest of Magna Graecia (present-day southern Italy and Sicily) and the Greek East brought back with them not just works of art, but also exposure to elaborate Hellenistic architectural environments, which they desired to emulate. If granted a triumph by the senate, generals constructed and consecrated public buildings to commemorate their conquests and house the spoils. By the late Republic, statues adorned basilicas, sanctuaries and shrines, temples, theaters, and baths. As individuals became increasingly enriched through the process of conquest and empire, statues also became an important means of conveying wealth and sophistication in the private sphere: sculptural displays filled the gardens and porticoes of urban houses and country villas. The fantastical vistas depicted in luxurious domestic wall paintings included images of statues as well. \^/

““After the transition from republic to empire, the opportunity to undertake large-scale public building projects in the city of Rome was all but limited to members of the imperial family. Augustus, however, initiated a program of construction that created many more locations for the display of statues. In the Forum of Augustus, the historical heroes of the Republic appeared alongside representations of Augustus and his human, legendary, and divine ancestors. Augustus publicized his own image to an extent previously unimaginable, through official portrait statues and busts, as well as images on coins. Statues of Augustus and the subsequent emperors were copied and exhibited throughout the empire. Wealthy citizens incorporated features of imperial portraiture into statues of themselves. Roman governors were honored by portrait statues in provincial cities and sanctuaries. The most numerous and finely crafted portraits that survive from the imperial period, however, portray the emperors and their families. \^/

““Summoning up the image of a "forest" of statues or a second "population" within the city, the sheer number of statues on display in imperial Rome dwarfs anything seen before or since. Many of the types of statues used in Roman decoration are familiar from the Greek and Hellenistic past: these include portraits of Hellenistic kings and Greek intellectuals, as well as so-called ideal or idealizing figures that represent divinities, mythological figures, heroes, and athletes. The relationship of such statues to Greek models varies from work to work. A number of those displayed in prestigious locations in Rome were transplanted Greek masterpieces, such as the Venus sculpted by Praxiteles in the fourth century B.C. for the inhabitants of the Greek island of Cos, which was set up in Rome's Temple of Peace, a museumlike structure set aside for the display of art. More often, however, the relationship to an original is one of either close copying or eclectic and inventive adaptation. Some of these copies and adaptations were genuine imports, but many others were made locally by foreign, mainly Greek, craftsmen.

A means of display highly characteristic of the Roman empire was the arrangement of statues in tiers of niches adorning public buildings, including baths, theaters, and amphitheaters. Several of the most impressive surviving statuary displays come from ornamental facades constructed in the Eastern provinces (Library of Celsus, Ephesus, Turkey). Bolstered by wealth drawn from around the Mediterranean, the imperial families established their own palace culture that was later emulated by kings and emperors throughout Europe. Exemplary of the lavish sculptural displays that decorated imperial residences is the statuary spectacle inside a cave employed as a summer dining room of the palace of Tiberius at Sperlonga, on the southern coast of Italy. Visitors to this cave were confronted with a panoramic view of groups of full-scale statues reenacting episodes from Odysseus' legendary travels.” \^/

Polychromy of Roman Marble Sculpture

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “When Roman marble sculpture was rediscovered in the Renaissance, it emerged from more than a millennium of burial essentially devoid of its ancient polychromy. The monochromatic appearance of these works gave rise to new, modern canons of sculpture characterized by an emphasis on form with little consideration of color. In antiquity, however, Greek and Roman sculpture was originally richly embellished with colorful painting, gilding, silvering, and inlay. Such polychromy, which was integral to the meaning and immediacy of such works, has largely been lost in burial and survives today only in fragmentary condition. [Source: Mark B. Abbe, Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Depictions of statuary in Roman wall paintings provide an indication of their diverse appearances in antiquity. Some marble sculptures were completely painted and gilded, effectively obscuring the marble surface; others had more limited, selective polychromy used to emphasize details such as the hair, eyes, and lips and accompanying attributes. \^/

“Roman artists used a wide range of pigments, painting media, and surface applications to embellish their marble sculptures. Ancient authors, especially Pliny the Elder and Vitruvius, provide important information about these materials and express great admiration for the virtuoso technique of contemporary sculptors who developed a technical refinement unparalleled in classical antiquity. White marble itself was prized for its brilliant translucency, ability to take finely carved detail, and flawless uniformity. A vast array of colored marbles and other stones were also quarried from throughout the Roman world to create numerous colorful statues of often dazzling appearance. \^/

“Burial, early modern restoration practices, and historic cleaning methods have all reduced the polychromy on Roman marble sculptures. Many works, however, preserve important evidence of their original polychrome decoration. Such remains are inevitably fragmentary and have altered over time, making it difficult to reconstruct their exact appearance in antiquity with certainty. Nevertheless, through a host of techniques—including microscopic examination, ultraviolet and infrared photography, and different types of material analysis—it is possible to gain valuable insight into the original appearance of these ancient works of art.

Imperial Porphyry — Ancient Rome’s Most Valuable Stone

A very expensive kind marble in Roman times was called ‘imperial porphyry.’ The emperors liked it because of its deep and distinctive purple color and the fact it was very rare and hard to come by. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: All imperial porphyry mined in the ancient world came from a single, remote quarry in the eastern part of Roman Egypt called the Mons Porphyrites. It was discovered in 18 B.C. when a Roman soldier named Caius Cominius Leugas noticed a hard purple-red rock in the desert. Technically porphyry (which just means “purple” in Greek) is an igneous rock containing coarse grained crystals. Most imperial purple marble was used as an accent stone in tiled floors or on columns. You can find it fashioned into vases or busts, but the basin from Nero’s Golden House is exceptionally large and heavy. It’s almost certainly the largest single intact piece of porphyry marble that exists today. The mine established at Mons Pophryites was used continuously until A.D. 600, when the Romans lost control of Egypt. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 27, 2022]

After it was extracted from the mines — which was no mean feat! — the material had to be transported. The journey began with a lengthy overland journey from the mine to the Nile. At Coptos, the marble boarded a ship up the river and carried on across the Mediterranean making stops along the way. The final leg of the journey, from the port of Ostia to the City of Rome also took place over land. Even for those not transporting heavy marble this was a lengthy journey that could take as long as 10 weeks. As Incunabula has put it on Twitter: “Imperial porphyry signaled not just power and prestige, but also that the Roman Empire could accomplish the near impossible: Cutting and quarrying the immensely hard rock, and transporting it 1000s of kilometers from the Egyptian desert to Rome was an awe-inspiring feat of engineering.”

It was the expense of moving the stuff that made imperial porphyry so expensive and exclusive. Vanden Eykel told me that imperial marble is immediately recognizable because of its distinctive marble hue. It signifies wealth and status. Just as having a white alligator Hermes Birkin says that you have connections and $150,000 to burn on a handbag, porphyry marble signaled to your guests that you were someone of import. What says that more, said Vanden Eykel, than “a gargantuan porphyry bathtub?” The only other porphyry objects of similar scale were tombs and coffins: Nero, the Holy Roman Emperors, and even Napoleon all chose it for their final resting places. Napoleon had to make do with a common red marble.

Like other luxury products, imperial porphyry were regularly imitated. Rosso antico marble (also known as Marmor Taenarium), a beautiful red marble mined in the southern Peloponnese, was one such imitator. It was used, as Lorenzo Lazzarini notes, “as a substitute of the red Egyptian porphyry.” Though it is beautiful, rosso antico lacks the speckles and deep purple of the Egyptian marble. If you wanted to get the imperial porphyry look today, you might try a rosso impero instead.

How the Giant Bronze Finger of Constantine Was Made

Bronze statues were made using the lost wax technique in which wax was used to make a clay mold. Roman ones were often embellished with silver or stone eyes, teeth and nails and copper eyelashes and nipples. Few bronze sculptures remain, most were melted down to make weapons, kitchen utensils or other items.

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: The 1.2-foot-long bronze index finger of a massive fourth-century statue currently on display at Rome’s Capitoline Museums, thought to depict the Roman emperor Constantine, has been rediscovered in the Louvre. Aurélia Azéma, now of the French Laboratory for Research on Historical Monuments, made the discovery after studying the finger — which came to Paris from a private collection in 1861 and was originally cataloged by curators as a “Roman toe” — for a doctoral dissertation on ancient bronze techniques. “The finger was an interesting case to illustrate manufacturing techniques, particularly the welding of colossal bronzes,” Azéma says. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2018]

Meanwhile, the pieces of the Constantine statue in Rome — which is thought to have stood nearly 40 feet tall — include an enormous head, a sphere, a left forearm, and a hand missing its palm, and were also important for her research. “In looking at the finger and comparing technological features with those of the Constantine statue, the similarities were everywhere,” she explains, “in size, casting, repairing, welding, and gilding.” The link between the finger and the statue was confirmed beyond all doubt when a team of Azéma’s colleagues from the Louvre and the French Center for Research and Restoration of Museums constructed a 3-D model of the finger and brought it to the Capitoline Museums for a fitting. “It was like two pieces of a puzzle,” Azéma says.

Roman Stuccowork

“Stucco has a long history in the Mediterranean world. Typically consisting of crushed or burned lime or gypsum mixed with sand and water, stucco was easily molded or modeled into relief decoration for walls, ceilings, and floors in both interior and exterior spaces. Stucco plaster was also used extensively in metalwork to form cores for Greek bronze sculpture and for cast impressions of bronze vessel decoration. [Source: Sarah Lepinski, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/stuc/hd_stuc.htm March 2012, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Roman stuccowork grew out of Hellenistic practices in the Mediterranean world, which, in turn, combined earlier Greek and Egyptian traditions. The ancient Greeks employed lime plaster in relief on walls to simulate monumental architecture and Egyptians used gypsum stucco for figural reliefs, freestanding sculpture, and other types of objects. \^/

“Following Greek tradition, Roman stuccowork used white lime plaster, which was lightweight and easily worked. This type of plaster was also used in contemporary fresco painting, and its preparation and application is described in detail by ancient authors such as Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder. Stuccowork grew in popularity in late Republican and early Imperial Italy as a result of the construction boom associated with brick and cement construction. While it is not as widely known today as other types of Roman decor, it played a significant role in well-planned and -executed interior spaces, complementing painted compositions, mosaic floors, and sculptural assemblages with projecting architectural elements and relief schemes. \^/

“Artists working in Roman Italy created expansive stucco schemes in private homes, tombs, and public buildings, particularly in baths. On walls, architectural members such as balustrades, column capitals, pilasters, columns, cornices, and frieze borders were fashioned in stucco and integrated into painted scheme. The stucco elements enhanced the two-dimensional decorative surfaces with projecting architectural members, adding a play of light and shadow to the interior spaces. The pieces in high relief were secured to the walls with metal rods or nails. Some forms were molded before they were attached to the walls, but other shapes and designs, such as cornices or frieze borders, were stamped into semi-dry plaster after application to the wall or ceiling. The stamped patterns imitated the egg-and-dart and vegetal borders carved on monumental architecture, a fashion that is also seen in contemporary Roman wall paintings, particularly those painted in the Second Pompeian Style. \^/

“The general compositions of Roman stuccowork on ceilings, vaulted arches, and lunettes in Imperial Roman structures also reflect architectural forms. Influenced by the sunken framework of coffered ceilings in Hellenistic and Republican buildings, which were built in both stone and wood, Roman stuccowork formed panels framed with stamped decorative borders and cornices. Within the panels, artists modeled vegetal forms, animals, items of armor, and mythological and imaginary figures. A series of stucco reliefs in the Metropolitan Museum, which originally belonged to a large arch composition, provides a vivid example of an early Imperial stuccoed vault. The panels depict single figures that were applied by hand after the white stucco background was partially set (in general, Roman stuccowork was left white, although in some situations the backgrounds were painted). A fingerprint impression in the stucco highlights the quick practice of modeling. The artist's deft handling of the stucco is apparent in the varying relief heights of the figures as well as the added details: incisions in the semi-dry stucco outline the forms and articulate the figures, clothing, and accoutrements; holes pierced in the soft stucco indicate eyes, hair, and ribbons. \^/

“The figures represented in the Museum's panels share associations with Dionysus/Bacchus, god of wine and prosperity. A snarling panther rears slightly with a ribbon falling across its back. The dancing female figures hold drums, thyrsoi, garlands, and a fruit bowl. Floating erotes also grasp thyrsoi and garlands, and one carries a cornucopia. A striding nude male figure, possibly a satyr, with a pelt on his shoulder, holds a hare in his left hand and a staff in his right. \^/

“The popularity of Dionysiac themes in Roman art, which were rendered in various media and contexts, reflects the deity's multifaceted nature in Roman culture. Dionysus was linked to banqueting, the theater, hunting, agriculture, and the afterlife. Set within a domestic context, Dionysus and his retinue convey an attitude of a civilized life in opulent surroundings. Figural panels evoke a sense of luxury and festivity not only with their subject matter but also with their material and artistic characteristics. These facets illustrate the extent to which stuccowork corresponded thematically with other decorative media and how it augmented interior spaces with a sense of dimension and play of light. Roman stucco traditions continued throughout late antiquity, in part influencing Sasanian and later Islamic traditions, and well after antiquity, as is attested, for instance, in late medieval and Renaissance traditions.

Tanagra Figurines

tanagra figure

Tanagras are a kind of terracotta figurines that entered the market by the last quarter of the fourth century B.C. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Appreciated for their naturalistic features, preserved pigments, variety, and charm, these figurines are known as Tanagras, from the site in Boeotia where great numbers of them were found. The majority of Tanagra figurines depict fashionable women or girls, elegantly wrapped in thin himations (cloaks), and sometimes wearing broad-brimmed hats and holding wreaths or fans. Previously, in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., terracotta statuettes had been produced in Athens primarily for religious purposes, or as souvenirs of the theater. In contrast, the entirely new repertoire of Tanagra terracottas was based on an intimate examination of the personal world of mortal women and children, occasionally young men, and other characters, who are believed to have had their origins in the New Comedy of Menander. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The variety of gesture and detail that makes Tanagra figurines so appealing is due to a fairly complex method of manufacture. Like most earlier terracotta statuettes, they were formed in concave terracotta molds. The original three-dimensional figure from which the mold was taken was usually handmade of wax or terracotta, although existing figurines of terracotta, bronze, or wood occasionally were used. Clay was pressed over this prototype and, when slightly hardened, it was removed, touched up, and fired in a kiln. \^/

“Until the mid-fourth century B.C., it was customary to mold only the front of the figure and to attach a simple unmodeled back; the hollow statuette was then fired. Tanagra figurines, however, were made in two-part molds—one for the front and one for the back. Often the heads and projecting arms were made in separate molds and attached to the statuette before firing. By varying the direction of the head and the position of the arms, a single type of figure could be given many slightly different poses. Wreaths, hats, or fans were handmade and separately attached. A rectangular plaque was added as a base, and vents were cut into the back of each statuette to allow moisture in the clay to escape during firing. A white slip, composed of clay and water, was applied to the entire statuette before it was fired. \^/

“After firing, the Tanagra figurines were brightly colored in a naturalistic manner with water-soluble paints. Red was used for hair, lips, shoes, and accessories, and black marked eyebrows, eyes, and other details. The flesh was painted a pale orange pink, and a reddish purple made from rose madder often was used for the drapery. Blue was used sparingly, as the pigment was expensive, and green, which was made from malachite, was never employed.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024