Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT ROMAN ART

Roman art tended to be realistic while Greek art was idealized. Roman artistic innovations included equestrian statues, naturalistic busts, and decorative wall paintings like those found in Pompeii. The Romans liked adorn their public and private buildings and spaces with art with color and texture. Perhaps their greatest contribution to art was their mosaics. The word style is derived from the word “stilus,” the Roman writing instrument.

A lot of Roman art was an imitation of Greek art, much of it poor imitations, and judging from the way the Romans wrote about Greek art and their own arts seems to show they realized this as well. Greek art and culture arrived in Rome indirectly through the Etruscans and more directly through Greek colonies in Italy and by Roman plundering of Greek cities and offers of good pay for Greek artists in Rome.

The historian William C. Morey wrote: “As the Romans were a practical people, their earliest art was shown in their buildings. While the Romans could never hope to acquire the pure aesthetic spirit of the Greeks, they were inspired with a passion for collecting Greek works of art, and for adorning their buildings with Greek ornaments. They imitated the Greek models and professed to admire the Greek taste; so that they came to be, in fact, the preservers of Greek art.” [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

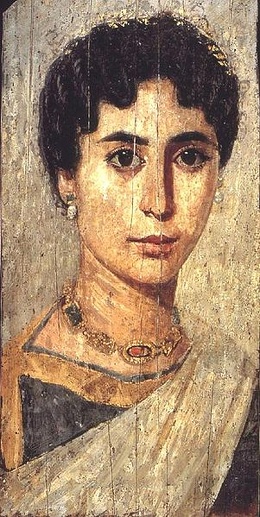

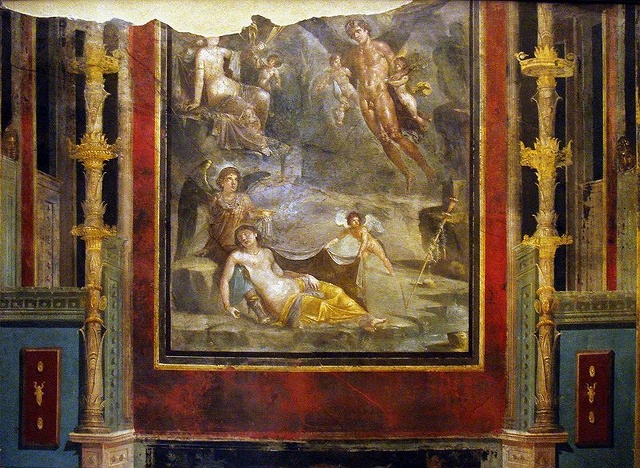

The dismissal of the Roman artists as mere copyists of the Greeks may be unfair. Maybe it is true with sculpture but is not true with painting as frescoes of Pompeii and the mummy shroud paintings in Roman-era Egypt show. The Romans were the first to employ the science of perspective in their art, a three-dimensional quality most notably employed in shroud paintings from the A.D. first to third century in the Egyptian areas of Hawara and Fayum but also present in some works from Pompeii. By comparison, some of the images of Greek vase paintings look like idealized stick figures. Perspective was not rediscovered until the Renaissance in the 13th century Italy.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN PAINTING: HISTORY, FRESCOES, TOMBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FOUR STYLES OF ANCIENT ROMAN PAINTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STUNNING, ROMAN-ERA, FAIYUM MUMMY PORTRAITS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE: HISTORY, TYPES, MATERIALS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS PIECES OF ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MOSAICS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMANS CRAFTS: POTTERY, STUFF IN THE SECRET CABINET factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN GLASS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Art” by Michael Siebler and Norbert Wolf (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Empire: 100-450 AD (Oxford History of Art) by Jaś Elsner Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Paul Zanker (2012) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art: Romulus to Constantine ” by Nancy H. Ramage, Andrew Ramage Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Steven L. Tuck Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Fred Kleiner Amazon.com;

“Roman Art: A Guide through The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Collection” by Paul Zanker, Seán Hemingway, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Life, Myth, and Art in Ancient Rome” by Tony Allan (2005) Amazon.com;

“Art and Religion in Ancient Rome” by Daniel C. Gedacht Amazon.com;

“Roman Art and Architecture” by Mortimer Wheeler (1971) Amazon.com;

“Art & Archaeology of the Roman World” by Mark Fullerton (2020) Amazon.com

“The Language of Images in Roman Art” by Tonio Hölscher (2004) Amazon.com;

“Power of Images in the Age of Augustus” by Paul Zanker and Alan Shapiro (1988) Amazon.com

“The Phantom Image: Seeing the Dead in Ancient Rome” by Patrick R. Crowley (2019) Amazon.com;

“Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia Minor”by Cornelius C. Vermeule (1968) Amazon.com;

“Classical Art: From Greece to Rome (Oxford History of Art) by Mary Beard, John Henderson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek & Roman Art” (Art Essentials) by Susan Woodford (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Tradition in Art” by Michael Greenhalgh, (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greece and Rome, From the Rise of Greece to the Fall of Rome”

by Giovanni Becatti (1967) Amazon.com;

“Images of Myths in Classical Antiquity” by Susan Woodford (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity” by John Boardman (1994) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Art” by Mark Stansbury-O'Donnell (2014) Amazon.com;

“Magna Graecia: Greek Art from South Italy and Sicily” by Aaron J. Paul (2002) Amazon.com;

Early Influences on Roman Art

Art and architecture flourished during the ancient Roman period. In the Roman Republic, the patrons had been private individuals, politicians vying for popular esteem, but during the Roman Empire emperors used art and architecture to advertise their virtues. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: From the 7th to the 3d century B.C., Etruscan art flourished throughout central Italy, including Latium and Rome. It was strongly influenced by the early art of Greece, although it lacked the basic sense of rational order and structural composition of the Greek models. The influence of native Italic and Middle Eastern art was also strongly felt, particularly during the archaic period (before c.400 B.C.). [Source: The Columbia Encyclopedia]

After the conquest of Greece (c.146 B.C.), Greek artists settled in Rome, where they found a ready market for works executed in the Greek classical manner or in direct imitation of Greek originals. While the many works by these copyists are of interest principally for their reflection of earlier Greek art, they throw light on the eclecticism of Roman taste, and their influence was of paramount importance throughout the development of Roman art. Roman portraits, however, have an origin very remote and altogether Italianate. It was a Roman custom to have a death mask taken, which was then preserved along with busts copied from it in terra-cotta or bronze.

Etruscan Art

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Much of what we know about the Etruscans comes not from historical evidence, but from their art and the archaeological record. Many Etruscan sites, primarily cemeteries and sanctuaries, have been excavated, notably at Veii, Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Vulci, and Vetulonia. Numerous Etruscan tomb paintings portray in vivid color many different scenes of life, death, and myth. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“From very early on, the Etruscans were in contact with the Greek colonies in southern Italy. Greek potters and their works influenced the development of Etruscan fine painted wares , and, consequently, new types of Etruscan pottery were created during the Orientalizing period (ca. 750–575 B.C.) and subsequent Archaic period (ca. 575–490 B.C.). The most successful of these pottery styles is known as Bucchero, characterized by its shiny black surface and preponderance of shapes that emulate metal prototypes. An Etruscan dedication at the Greek sanctuary of Delphi attests to the close interaction between the Greeks and the Etruscans in the Archaic period. The Etruscans particularly prized finely painted Greek vases, which they collected in great numbers. Likewise, their interest in Greek art and culture is manifest in works by Etruscan artists. However, the adaptation of Greek iconography to Etruscan art is complex and difficult to interpret. \^/

“Etruria, the region occupied by the Etruscans, was rich in metals, particularly copper and iron. The Etruscans were master bronze smiths who exported their finished products all over the Mediterranean. Finely worked bronzes, such as thrones and chariots decorated with exquisite hammered reliefs, cast statues and statuettes, as well as ornate vessels, mirrors, and stands, attest to the high quality achieved by Etruscan artists, particularly in the Archaic and Classical (ca. 490–300 B.C.) periods. Opulent jewelry of gold and semi-precious stones exemplifies eastern Greek and Levantine forms adapted to Etruscan taste. Extensive trade in the Mediterranean during this period supplied artists with exotic materials such as ivory, amber, ostrich eggs, and semi-precious stones, all of which fostered the development of Etruscan gem engraving and other arts. The Etruscans were also well known for their terracotta freestanding sculpture and architectural reliefs. Etruscan funerary works, particularly sarcophagi and cinerary urns , often carved in high relief, comprise an especially rich source of evidence for artistic achievement during the Late Classical and Hellenistic periods.

See Separate Article: ETRUSCAN ART: TOMB FRESCOES, GOLD GRAVE GOODS AND BRONZE STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com

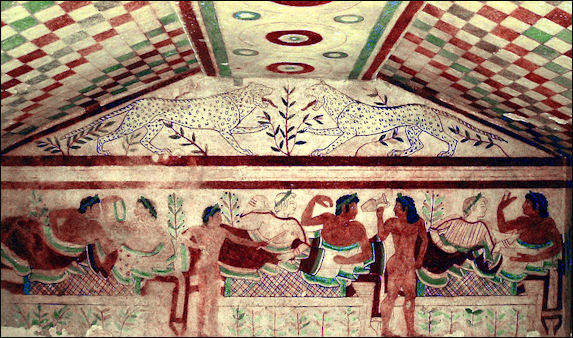

Etruscan Tarquinia Tomb of the Leopards

Etruscan Tomb Art

Tomb paintings include images of funeral ceremonies, athletic competitions, bloody duels, grand banquets, warriors and horsemen, demons and mythical creatures, and journeys to the next world. There are images of bearded snakes, dolphins, flocks of birds, musicians, wild dancers and jugglers. The vibrant colors were created with an array of pigments, some of them quite rare and expensive: white from calcite, red from hematite, black from charcoal, yellow from goethite, and blue from a mixture if silica, lime, copper and a special alkali imported from Egypt.

Few of the tombs with wall paintings are open to the public. Once a sealed tomb has been opened the paintings decays rapidly in the humidity. One tomb called the Tomb of the Leopards has beautiful wall paintings that depict nude wrestlers, men playing musical and a banqueting couple looking upon an egg, a symbol of immortality.

The Etruscan Museum in the Vatican contains one of the world's best collections of Etruscan art. The most outstanding pieces, which were found in Etruscan tombs in Tuscany and Lazio, include gold and silver jewelry, dice that looks just like modern dice, chariots, vase paintings, and small sarcophagi that held the cremated remains of wealthy Etruscans. Among the highlights are lovely Etruscan painting and a bronze statue of boy from the Etruscan site of Tarquina.

Arts Under Augustus and Trajan

Augustus (reigned 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) promoted learning and patronized the arts. Virgil, Horace, Livy and Ovid wrote during the “Augustan Age," Augustus also established what has been described as the first paleontology museum on Capri. It contained the bones of extinct creatures. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the reign of Augustus, Rome was transformed into a truly imperial city. By the first century B.C., Rome was already the largest, richest, and most powerful city in the Mediterranean world. During the reign of Augustus, however, it was transformed into a truly imperial city. Writers were encouraged to compose works that proclaimed its imperial destiny: the Histories of Livy, no less than the Aeneid of Virgil, were intended to demonstrate that the gods had ordained Rome "mistress of the world." A social and cultural program enlisting literature and the other arts revived time-honored values and customs, and promoted allegiance to Augustus and his family. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

The emperor was recognized as chief state priest, and many statues depicted him in the act of prayer or sacrifice. Sculpted monuments, such as the Ara Pacis Augustae built between 14 and 9 B.C., testify to the high artistic achievements of imperial sculptors under Augustus and a keen awareness of the potency of political symbolism. Religious cults were revived, temples rebuilt, and a number of public ceremonies and customs reinstated. Craftsmen from all around the Mediterranean established workshops that were soon producing a range of objects—silverware, gems, glass—of the highest quality and originality. Great advances were made in architecture and civil engineering through the innovative use of space and materials. By 1 A.D., Rome was transformed from a city of modest brick and local stone into a metropolis of marble with an improved water and food supply system, more public amenities such as baths, and other public buildings and monuments worthy of an imperial capital.” \^/

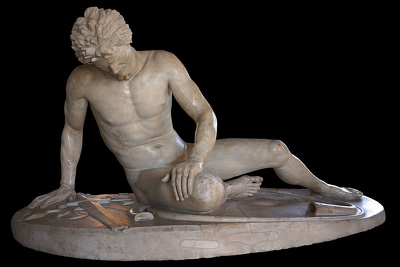

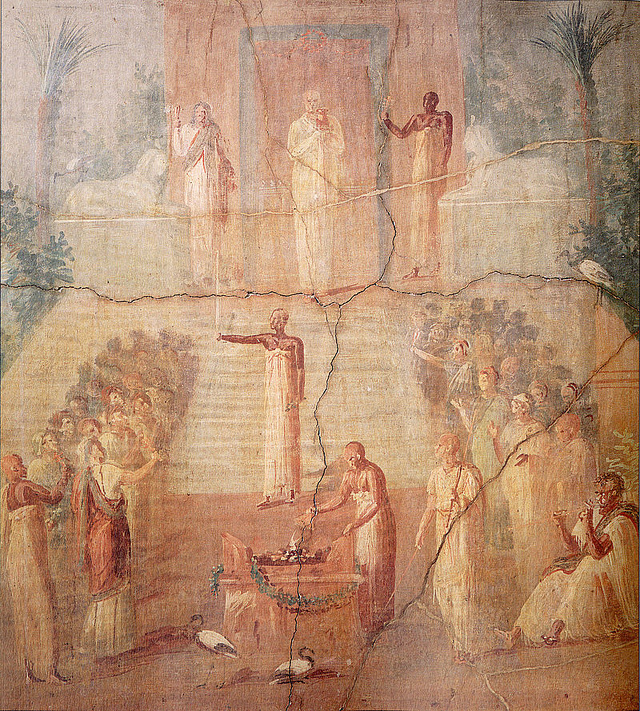

During Trajan’s reign (98–117 A.D.) period Roman art reached its highest development. The art of the Romans, as we have before noticed, was modeled in great part after that of the Greeks. While lacking the fine sense of beauty which the Greeks possessed, the Romans yet expressed in a remarkable degree the ideas of massive strength and of imposing dignity. In their sculpture and painting they were least original, reproducing the figures of Greek deities, like those of Venus and Apollo, and Greek mythological scenes, as shown in the wall paintings at Pompeii. Roman sculpture is seen to good advantage in the statues and busts of the emperors, and in such reliefs as those on the arch of Titus and the column of Trajan. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Luxury Arts of Rome

Christopher Lightfoot of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “During the late Republic, wealth poured into Rome on an unprecedented scale in the form of tribute, taxes, and profits from commerce and banking. Not all of the riches were honestly or legitimately acquired, for some came in the form of booty and spoils, including defeated enemies of Rome that were enslaved. It did mean, however, that a few leading men, such the general and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus (ca. 115–53 B.C.), became enormously rich. Such wealth was used principally to secure success in the intense political rivalry that afflicted Rome at that time, but it also stimulated patronage of the arts, the formation of libraries and art collections, and the construction of palaces and gardens. [Source: Christopher Lightfoot, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Although Rome's first emperor, Augustus, attempted to curb these extravagances and excessive displays of personal wealth, well-to-do Romans increasingly indulged their taste for luxury during the Julio-Claudian period (27 B.C.–68 A.D.). In addition to spending fortunes on sumptuous villas, lavish entertainment, fashionable clothes, and entourages of slaves and hangers-on, men and women in high Roman society furnished themselves with a range of expensive personal items. Alon with gold jewelry such as earrings, necklaces, and finger rings, the Romans loved expensive silver mirrors, ivory combs and hairpins, and an assortment of boxes and containers for perfumes and cosmetics. These precious items give an indication of the variety and quality of the craftsmanship that was required to provide for the needs of wealthy Roman clients. Other accessories, known only from literary sources, were in more perishable materials, such as costly silks imported from China or flamboyant wigs made from the hair of German or British slaves. Ivory was also imported to Rome mainly from Africa via the Nile. \^/

“Roman ladies also developed a taste for elaborate jewelry decorated with colorful, exotic stones. Amber and pearl were two of the most popular and sought after materials; the former was brought from the Baltic Sea, and the finest pearls were imported from the Persian Gulf, although one reason given to justify the conquest of Britain during the reign of emperor Claudius (41–54 A.D.) was that it was a rich source of pearls. Other rare and expensive gems included amethysts, sapphires, and uncut diamonds, all from various parts of southern Asia. These were prized for their brilliancy and transparency. Emeralds from the eastern desert of Upper Egypt were also very popular; they were usually left in their natural form as prisms, which were drilled and strung on gold necklaces, bracelets, and earrings. Many funerary portraits of women—particularly the painted mummy portraits from Roman Egypt (examples of which are on display in the Egyptian galleries) and the sculpted stone portraits from the caravan city of Palmyra in Syria (examples are exhibited in the Ancient Near East galleries)—show the deceased wearing such jewelry as a lasting indication of their social status and personal wealth. \^/

“Some luxury materials were so rare or costly that they gave rise to cheaper, manmade imitations in both pottery and glass, but even in these we can recognize a technical and artistic skill of the highest caliber. Such is the case with mosaic glass and marbled ceramic tablewares, made to reproduce the striking patterns of banded agate. Cameo glass, the most difficult and costly of all Roman glass, was also inspired by layered semiprecious stones. There are, for example, many Roman gems in cameo glass that were made as less expensive alternatives to real cameos in banded agate or sardonyx. In addition, it must be remembered that much has been irretrievably lost, especially objects in gold and silver, which could easily be melted down and reused. Others became heirlooms and relics that were later incorporated into medieval and Renaissance works, such as some of the semiprecious stone vessels in the Treasury of San Marco in Venice. \^/

“In the third century A.D., the Roman empire was beset by barbarian invasions in Europe, a renascent Sasanian Persian empire in the East, internal disorder, and rampant inflation. Nevertheless, the empire's accumulated resources meant that the privileged elite in Roman society continued to enjoy a life of untold wealth and luxury. One result of the increased dangers was that people buried their precious possessions and failed more often to return to collect them. Hoards of silver and jewelry have consequently been found in considerable numbers throughout the Roman world. There was certainly no diminution of skill and inventiveness of the craftsmen who produced these luxuries, but new styles in design and fashion developed. In particular, jewelry and ornaments became more colorful and garish, and they included the use of gold coins (an attractive but practical way to beat inflation). Such tastes led ultimately to the adoption by the emperors of ceremonial silk robes and regal-looking gold crowns, decorated with pearls and precious stones. It was to be a fashion that greatly influenced later Byzantine art, and even in the West the rulers of the successor kingdoms never completely forgot the wealth and splendor of ancient Rome.

Art of the Roman Provinces

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “At its greatest extent, the empire ruled by Rome reached around the Mediterranean Sea and stretched from northern England to Nubia, from the Atlantic to Mesopotamia. Roman rule united this vast and varied territory, and Roman administration integrated it economically and socially. A traveler making a tour of the several provinces around 212 A.D. (when citizenship was extended to all free-born males) would have found many similarities among the places that he or she visited: Roman coins circulated everywhere, and in every province there were cities adorned with statues of the emperor and buildings such as baths, basilicas, and amphitheaters that embodied Roman cultural and architectural norms. Each region nevertheless had its own history, its own local culture, and its own relationship with Rome. Art demonstrates both the scope and the limits of Roman influence, for the circulation of materials, methods, objects, and art forms created a certain cultural unity, and yet in each place, the persistence of local customs ensured the survival of cultural diversity. [Source: Jean Sorabella, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Gaul, a large region that roughly corresponds to modern France, provides a representative picture of the interaction between Roman and non-Roman traditions in the visual arts. Before the arrival of the Romans, metalwork was a highly developed craft among the Celts, whose artisans excelled in enriching metal objects with brightly colored abstract ornament; they seldom represented the human form, but when they did, they produced highly stylized figures quite alien to classical ideals. After the Romans arrived, Gallic craftsmen continued to work metal in sophisticated ways, but their output changed to serve the needs of society as it adopted Roman manners. Workshops in Gaul turned to produce vessels and tableware suited to a Romanized style of dining; they also applied techniques that the Romans admired, such as champlevé enamel, to ornaments designed for Roman buyers. Some objects made in Gaul were meant for local use, like statuettes of native divinities with distinctly un-Roman traits; other types of work were widely exported, such as six-sided boxes decorated with millefiore enamel and fine relief pottery known as terra sigillata. In addition to producing works of art, the people of Gaul also imported objects, expertise, and stylistic preferences from the capital: the cities of the province were thus outfitted with monumental statuary and buildings of Roman types, and the environs of these cities were served by roads and aqueducts. \^/

“The provinces of northern Africa also saw urban development in the Roman mold. The city of Timgad (modern-day Algeria), established by Trajan in 100 A.D., made use of a rigidly ordered grid plan, common to colonial settlements all over the empire, and some of the best preserved examples of Roman public buildings, including a theater, ampitheater, temple, and marketplace, are still to be found in Leptis Magna (in modern-day Libya), the birthplace of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211). Romanization went hand in hand with economic prosperity, as the city of Rome looked to North Africa to supply its wheat, oil, and wine, and agricultural productivity no doubt contributed to the distribution around the Mediterranean of distinctive red slip pottery vessels produced in Tunisian workshops. In many respects, the North African provinces became as Roman as any on the Italian peninsula, spawning intellectual figures steeped in Roman learning, such as the novelist Apuleius of Madaurus (ca. 125–ca. 180 A.D.) and the Christian writers Tertullian (ca. 160–ca. 220 A.D.) and Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430 A.D.). Their public and private spaces were adorned with the markers of Roman prosperity: courtyards and gardens, conspicious displays of freestanding sculpture, and, most especially, elegant and original mosaics, an art form for which North African artists showed particular talent. \^/

“The artistic output of each of the Roman provinces represents a mix of local and imperial traditions. Subject people continued to use their native languages, although official business was conducted in Latin or Greek; indigenous religions persisted, although sacrifices were everywhere offered for the emperor and the gods of the Roman pantheon. Visual culture too reflected the hybrid character of provincial civilization. Images of Roman style and message circulated widely, and yet craftsmen and consumers in the provinces maintained their own traditions, adopting Roman techniques and tastes as it suited them. \^/

“The funerary arts of the provinces demonstrate the variety and freedom of artistic expression in the several regions of the Roman empire. Since portraits and grave goods figure in many of the customs used to commemorate the dead, they also reflect the different styles of dress and approaches to representation preferred in various places. In Noricum and Pannonia in the Danubian basin, for instance, it was common to mark burials with busts of the deceased carved in relief, often in a naturalistic style like that used in Roman portraits and sometimes framed with moldings of classical design. The men depicted usually wear the toga, the proud costume of the Roman citizen, but the women sport instead a distinctive native fashion, with collars of heavy jewelry, prominent brooches at the shoulders, and cylindrical hats adorned with veils. The funerary portraiture of the Fayum oasis in Egypt displays a different mix of cultural preferences. The people here perpetuated the ancient custom of mummification, replacing the sculpted mask of earlier practice with a painted portrait. The context of these pictures is decidedly Egyptian, but the style of representation reflects the Greek tradition: the most refined examples demonstrate a remarkable degree of naturalism, and the costumes and hairstyles worn by both men and women adhere closely to Roman imperial fashions. The people of Palmyra in present-day Syria buried their dead in compartments cut into the walls of extensive cemetery complexes and closed each tomb with a limestone relief bearing a likeness of the dead. Some of the figures represented assume Roman garb and manners, but many more appear in oriental dress, with jewelry of local design; nearly all depict their subjects frontally, with disproportionately large eyes and boldly schematized features that display an approach to portraiture quite independent of Roman tendencies. \^/

“The diversity of customs followed in the disparate regions naturally resulted in artistic variety, but practices imposed by the Romans and observed throughout the empire also produced a lively range of responses. For example, the organization of urban society in the provinces granted high position to local elites, and members of this class often furnished their cities with buildings, monuments, and entertainments intended to display adherence to Roman ideals as well as the donor's largesse. For example, a local landholder who had been high priest in the cult of the Roman emperor erected an arch of recognizably Roman design at Saintes in southern France in 19 A.D., and in Barcelona in the early second century A.D., a father and son who both had attained senatorial rank and held consular office constructed a public bath on their own land. Sometimes the population of a whole town obtained imperial permission to set up a statue of the emperor or to build a temple in his honor. For the most part, such monuments took conventional forms: the emperor's portrait usually conformed to an official type probably devised in Rome itself. Some honorific images, however, reflected local traditions as well as or instead of the Roman standard. In the Greek-speaking lands of the eastern Mediterranean, for instance, the emperor's likeness was often mounted on an ideal nude body, as was common in the Hellenistic royal statues familiar there, and along the Nile, at Dendur, local people built a small temple on Egyptian architectural principles and decorated it with reliefs depicting the emperor Augustus in the guise of a pharaoh bringing offerings to Egyptian deities. \^/

“Finally, Roman rule facilitated trade among disparate regions, and this had a profound impact on art in the provinces. The circulation of marble and minerals suited to making pigments bound disparate regions to the capital and made possible the many-colored richness of much Roman architecture; the different types of stone used in the Pantheon, for instance, include yellow marble (giallo antico) from Tunisia, dramatically veined marble (pavonazzetto) from Asia Minor, green marbles from parts of Greece, flecked granites and deep red porpyhry from Egypt. The Romans also recognized and encouraged local industries in ways that ensured a wide range to some provincial products; iron works in Gaul and the Danubian basin, for example, operated as imperial manufactories producing weapons for Roman soldiers, and the Roman taste for glass ensured support first for the flourishing glassworks of Palestine and then for the proliferation of glass vessels and glass-making techniques throughout the empire. The army brought many Roman customs and products to distant locales, for recruits were often steeped in Roman culture even if they hailed from the provinces; excavations of military installations throughout the provinces have yielded glassware and small-scale statuary of standard Roman style. Philostratus, a Greek writer living in Rome in the third century A.D., marveled at the accomplished champlevé enamel of "barbarian" artists living in Gaul and Britain. Colorful enamel objects, from brooches to vessels to horse trappings, survive from sites throughout the empire and attest to the widespread appreciation for the distinctive achievements of artists working in its outer territories.

Secret Cabinet and the National Archaeological Museum in Naples

The National Archaeological Museum in Naples is one of the largest and best archeological museums in the world. Located with a 16th century palazzo, it houses a wonderful collection of statues, wall paintings, mosaics and everyday utensils, many of them unearthed in Pompeii and Herculaneum. In fact, most of the outstanding and well-preserved pieces from Pompeii and Herculaneum are in the archeological museum.

The National Archaeological Museum in Naples is one of the largest and best archeological museums in the world. Located with a 16th century palazzo, it houses a wonderful collection of statues, wall paintings, mosaics and everyday utensils, many of them unearthed in Pompeii and Herculaneum. In fact, most of the outstanding and well-preserved pieces from Pompeii and Herculaneum are in the archeological museum.

Among the treasures are majestic equestrian statues of proconsul Marcus Nonius Balbus, who helped restore Pompeii after the A.D. 62 earthquake; the Farnese Bull, the largest known ancient sculpture; the statue of Doryphorus, the spear bearer, a Roman copy of one of classical Greece's most famous statues; and huge voluptuous statues of Venus, Apollo and Hercules that bear witness to Greco-Roman idealizations of strength, pleasure, beauty and hormones.

The most famous work in the museum is the spectacular and colorful mosaic known both as “the Battle of Issus “ and “Alexander and the Persians” . Showing Alexander the Great battling King Darius and the Persians,, the mosaic was made from 1.5 million different pieces, almost all of them cut individually for a specific place on the picture. Other Roman mosaics range from simple geometric designs to breathtaking complex pictures.

Also worth look are the most outstanding artifacts found at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum are located here. The most unusual of these are the dark bronze statues of water carriers with spooky white eyes made of glass paste. A wall painting of peaches and a glass jar from Herculaneum could easily be mistaken for a Cezanne painting. In another colorful wall painting from Herculaneum a dour Telephus is being seduced by a naked Hercules while a lion, a cupid, a vulture and an angel look on.

Other treasures include the statue of an obscene male fertility god eying a bathing maiden four times his size; a beautiful portrait of a couple holding a papyrus scroll and a waxed tablet to show their importance; and wall paintings of Greek myths and theater scenes with comic and tragic masked actors. Make sure to check out the Farnese Cup in the Jewels collection. The Egyptian collection is often closed.

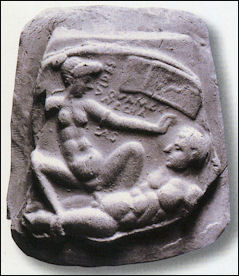

The Secret Cabinet (in National Archaeological Museum) is a couple of rooms with erotic sculptures, artifacts and frescoes from ancient Rome and Etruria that were locked away for 200 years. Unveiled in the year 2000, the two rooms contain 250 frescoes, amulets, mosaics, statues, oil laps,, votive offerings, fertility symbols and talismans. The objects include a second-century marble statute of the mythological figure Pan copulating with a goat found at the Valli die Papyri un 1752. Many of the objects were found in bordellos in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The collection began with as a royal museum for obscene antiques started by the Bourbon King Ferdinand in 1785. In 1819, the objects were moved to a new museum where they were displayed until 1827, when it was closed after complaints by a priest that descried the room as hell and a "corrupter of the morals or modest youth." The room was opened briefly after Garibaldi set up a dictatorship in southern Italy in 1860.

Porphyry: On Images

Porphyry (A.D. c. 234 – c. 305) was a leading "Neoplatonist", who sought to defend "reason". As Christianity spread, there was a strong, negative intellectual reaction to it among the classically oriented intellectuals. In some of his works he attacks Christian unreason. In others he defends traditional Roman (Pagan) religion. The following fragments, passed on to use by Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), are related to cult images and images of Roman-era gods.

Porphyry wrote: Fragment 1: “I speak to those who lawfully may hear: Depart all ye profane, and close the doors. The thoughts of a wise theology, wherein men indicated God and God's powers by images akin to sense, and sketched invisible things in visible forms, I will show to those who have learned to read from the statues as from books the things there written concerning the gods. Nor is it any wonder that the utterly unlearned regard the statues as wood and stone, just as also those who do not understand the written letters look upon the monuments as mere stones, and on the tablets as bits of wood, and on books as woven papyrus.” [Source: “On Images” Porphyry (A.D. 232/3-c.305), drawn from fragments in Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), translated by Edwin Hamilton Gifford, MIT]

Fragment 2: “As the deity is of the nature of light, and dwells in an atmosphere of ethereal fire, and is invisible to sense that is busy about mortal life, He through translucent matter, as crystal or Parian marble or even ivory, led men on to the conception of his light, and through material gold to the discernment of the fire, and to his undefiled purity, because gold cannot be defiled. On the other hand, black marble was used by many to show his invisibility; and they moulded their gods in human form because the deity is rational, and made these beautiful, because in those is pure and perfect beauty; and in varieties of shape and age, of sitting and standing, and drapery; and some of them male, and some female, virgins, and youths, or married, to represent their diversity. Hence they assigned everything white to the gods of heaven, and the sphere and all things spherical to the cosmos and to the sun and moon in particular, but sometimes also to fortune and to hope: and the circle and things circular to eternity, and to the motion of the heaven, and to the zones and cycles therein; and the segments of circles to the phases of the moon; pyramids and obelisks to the element of fire, and therefore to the gods of Olympus; so again the cone to the sun, and cylinder to the earth, and figures representing parts of the human body to sowing and generation.”

Fragment 4: “They have made Hera the wife of Zeus, because they called the ethereal and aerial power Hera. For the ether is a very subtle air.”

Fragment 5: “And the power of the whole air is Hera, called by a name derived from the air: but the symbol of the sublunar air which is affected by light and darkness is Leto; for she is oblivion caused by the insensibility in sleep, and because souls begotten below the moon are accompanied by forgetfulness of the Divine; and on this account she is also the mother of Apollo and Artemis, who are the sources of light for the night.”

Fragment 6: “The ruling principle of the power of earth is called Hestia, of whom a statue representing her as a virgin is usually set up on the hearth; but inasmuch as the power is productive, they symbolize her by the form of a woman with prominent breasts. The name Rhea they gave to the power of rocky and mountainous land, and Demeter to that of level and productive land. Demeter in other respects is the same as Rhea, but differs in the fact that she gives birth to Kore by Zeus, that is, she produces the shoot from the seeds of plants. And on this account her statue is crowned with ears of corn, and poppies are set round her as a symbol of productiveness.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see MIT Classics classics.mit.edu

Ancient Roman Sculpture

Heroic statue of Augustus While the Greeks made sculptures of idealized human forms, the Roman tended to make portraits. Romans made sculptures of gods, heroes, emperors, generals and politicians. They also used sculpted images to adorn the capitals of columns and the helmets of gladiators. Roman sculptures often reflected the fashions and lifestyles that were prevalent when they were made. Archaeologists can even date sculptures of Roman by their hairdos and clothing styles. During the Augustan Age, for example, women parted their hair in the middle with a central roll. The Flauvians and Antiones had more elaborate coiffures that resembled a honeycomb of curls. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Sculpture were made spectacular-looking but hard to work stone such as porphyry from Gebel Dokhan in northeast Egypt, basanite granite from Gebel Fatireh in eastern Egypt, and blue, yellow, green, black and grey marble from elsewhere in the empire.

Paintings in Ancient Rome

The Romans were the first to employ the science of perspective in their art, a three-dimensional quality most notably employed in shroud paintings from the A.D. first to third century in the Egyptian areas of Hawara and Fayum but also present in some works from Pompeii. Perspective was not rediscovered until the Renaissance in the 13th century Italy.

Most of what is left of Roman painting comes from Pompeii. Pompeii is the source of what we know about a lot of things from ancient Rome. Paintings have also been found in other places, most notably in villas and tombs. In the mid-1990s, workers digging a foundation in Marsala, Sicily found a Roman tomb with paintings of angels, flowers, figures and baskets. Reached by a narrow flight of stairs, the 16-16-foot room was dated to A.D. 300.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The history of Roman painting is essentially a history of wall paintings on plaster. Although ancient literary references inform us of Roman paintings on wood, ivory, and other materials, works that have survived are in the durable medium of fresco that was used to adorn the interiors of private homes in Roman cities and in the countryside. According to Pliny, it was Studius "who first instituted that most delightful technique of painting walls with representations of villas, porticos and landscape gardens, woods, groves, hills, pools, channels, rivers, and coastlines." Despite the lack of physical evidence, we can assume that many portable paintings depicted subjects similar to those found on the painted walls in Roman villas. It is also reasonable to suppose that Roman panel paintings, which included both original creations and adaptations of renowned Hellenistic works, were the prototypes for the myths depicted in fresco. Roman artists specializing in fresco most likely traveled with copybooks that reproduced popular paintings, as well as decorative patterns. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024