Home | Category: Art and Architecture

PAINTINGS IN ANCIENT ROME

The Romans were the first to employ the science of perspective in their art, a three-dimensional quality most notably employed in shroud paintings from the A.D. first to third century in the Egyptian areas of Hawara and Fayum but also present in some works from Pompeii. Perspective was not rediscovered until the Renaissance in the 13th century Italy.

Most of what is left of Roman painting comes from Pompeii. Pompeii is the source of what we know about a lot of things from ancient Rome. Paintings have also been found in other places, most notably in villas and tombs. In the mid-1990s, workers digging a foundation in Marsala, Sicily found a Roman tomb with paintings of angels, flowers, figures and baskets. Reached by a narrow flight of stairs, the 16-16-foot room was dated to A.D. 300.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The history of Roman painting is essentially a history of wall paintings on plaster. Although ancient literary references inform us of Roman paintings on wood, ivory, and other materials, works that have survived are in the durable medium of fresco that was used to adorn the interiors of private homes in Roman cities and in the countryside. According to Pliny, it was Studius "who first instituted that most delightful technique of painting walls with representations of villas, porticos and landscape gardens, woods, groves, hills, pools, channels, rivers, and coastlines." Despite the lack of physical evidence, we can assume that many portable paintings depicted subjects similar to those found on the painted walls in Roman villas. It is also reasonable to suppose that Roman panel paintings, which included both original creations and adaptations of renowned Hellenistic works, were the prototypes for the myths depicted in fresco. Roman artists specializing in fresco most likely traveled with copybooks that reproduced popular paintings, as well as decorative patterns. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FOUR STYLES OF ANCIENT ROMAN PAINTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STUNNING, ROMAN-ERA, FAIYUM MUMMY PORTRAITS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE: HISTORY, TYPES, MATERIALS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MOSAICS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Painting”, Illustrated, by Roger Ling Amazon.com;

“Roman Painting”, lots of images, by Amedeo Maiuri (1953) Amazon.com;

“The Splendor of Roman Wall Painting” by Umberto Pappalardo Amazon.com;

“Domus: Wall Painting in the Roman House” by Donatella Mazzoleni , Umberto Pappalardo, et al. (2005) Amazon.com;

“Painting Pompeii: Painters, Practices, and Organization” by Francesca Bologna (2024) Amazon.com;

“Fausto & Felice Niccolini: Houses and Monuments of Pompeii”

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pompeii”, Illustrated, by Joanne Berry (2007) Amazon.com;

by Valentin Kockel (2016) Amazon.com;

“Shaping Roman Landscape: Ecocritical Approaches to Architecture and Wall Painting in Early Imperial Italy” by Mantha Zarmakoupi (2023) Amazon.com;

“Roman Landscapes: Visions of Nature and Myth from Rome and Pompeii”

by Jessica Powers (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Social Life of Painting in Ancient Rome and on the Bay of Naples”

by Eleanor Winsor Leach (2004) Amazon.com;

“Painting, Ethics, and Aesthetics in Rome” by Nathaniel B. Jones Amazon.com;

“The Phantom Image: Seeing the Dead in Ancient Rome” by Patrick R. Crowley (2019) Amazon.com;

“Art of Empire: The Roman Frescoes and Imperial Cult Chamber in Luxor Temple”

by Michael Jones and Susanna McFadden (2015)

Amazon.com;

“Mysterious Fayum Portraits” by Euphrosyne Doxiadis (1995, 2025) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt” by Susan Walker (1997) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Michael Siebler and Norbert Wolf (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Empire: 100-450 AD (Oxford History of Art) by Jaś Elsner Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Paul Zanker (2012) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art: Romulus to Constantine ” by Nancy H. Ramage, Andrew Ramage Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Steven L. Tuck Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Fred Kleiner Amazon.com;

“Art & Archaeology of the Roman World” by Mark Fullerton (2020) Amazon.com

“The Language of Images in Roman Art” by Tonio Hölscher (2004) Amazon.com;

“Power of Images in the Age of Augustus” by Paul Zanker and Alan Shapiro (1988) Amazon.com

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Tradition in Art” by Michael Greenhalgh, (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greece and Rome, From the Rise of Greece to the Fall of Rome”

by Giovanni Becatti (1967) Amazon.com;

History of Ancient Roman Painting

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: Roman painting, like sculpture, was strongly influenced by the art of Greece. Unfortunately, much of the painting has perished. What remains suggests that the art was conceived principally as one of interior decoration. Aside from encaustic portraits chiefly of Alexandrian origin, the largest single group of Roman paintings is from Pompeii, although parallel work exists elsewhere. The Incrustation, or Architectonic Plastic, style extended to around 80 B.C.; it was characterized by flat areas of color broken by full-scale painted pilasters in apparent imitation of marble slabs. [Source: The Columbia Encyclopedia]

The Architectural style that followed lasted 70 years; it was largely influenced by stage design and employed painted columns, arches, entablatures, and pediments to frame landscapes and figure compositions, destroying the architectonic quality of the wall. Many famous paintings, such as the Aldobrandini Wedding and Odyssey Landscapes (Vatican), are believed to be Roman copies of Greek originals.

By 10 B.C. the Architectural style yielded to the Ornate style, where the semblance of architectural construction became subordinate to decoration, and the paintings within the borders became prominent. Most surviving Pompeiian paintings date from the Intricate style period, which commenced about A.D. 50 and continued until the destruction of the city in AD 79 by the eruption of Vesuvius. Large areas of flat color enclose diminutive, graceful, and delicate scenes executed in brilliant color.

Frescoes in Ancient Rome

The Romans adorned the walls of palaces and villas with frescoes. Today, a fresco has come to mean any painting painted on a plaster or stucco wall. In the old days, it meant a painting on a stucco wall which had not dried yet. “Fresco” is an Italian word that means “fresh," a reference to the fact that plaster was still wet when the painting was made.

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Although frescoes appear to exist as a single layer on a wall, they are actually created in multiple layers in a way that makes the artwork part of the wall itself. True fresco is made by beginning with several coats of plaster — usually two rough coats that are allowed to dry and harden, and a third, smooth one. Dry pigments mixed with water are painted on while the third coat is still wet. As this uppermost layer dries, the painting becomes part of the wall, creating a durable surface that can last for hundreds, indeed thousands, of years, unlike an oil painting on canvas, for example, which can easily peel or chip. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2014]

Roman made frescoes employing a technique known as buon fresco, using water- based pigments on a wet plaster wall. Especially during the rule of Augustus (63 B.C. to A.D. 14) fresco painting was all the rage, with images of gods, gardens and other landscapes in large interior spaces. Frescoes painters often didn't know exactly how their works would look until the paint dried. The colors looked different when they were soaked into the plaster.

To make a Roman fresco: 1) slow-drying plaster was applied to a wall with a mason's trowel; 2) before the wall surface hardened, the surface was smoothed with a sanding stone to produce a finish as smooth as marble; 3) background colors were applied before the hardening took places; 4) details were added with pigments that are mixed with honey or egg whites.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Some of the best evidence for the techniques of Roman wall painting is in Pliny's Natural History and in Vitruvius' manual De Architectura. Vitruvius describes the elaborate methods employed by wall painters, including the insertion of sheets of lead in the wall to prevent the capillary action of moisture from attacking the fresco, the preparation of as many as seven layers of plaster on the wall, and the use of marble powder in the top layers to produce a mirrorlike sheen on the surface. Preliminary drawings or light incisions on the prepared surface guided the artists in decorating the walls a fresco (on fresh plaster) with bold primary colors. Softer, pastel colors were often added a secco (on dry plaster) in a subsequent phase. Vitruvius also informs us about the pigments used by the Roman artist. Black was drawn from the carbon created by burning brushwood or pine chips. Ocher was extracted from mines and served for yellow. Red was derived either from cinnabar, red ocher, or from heating white lead. Blue was made from mixing sand and copper, and then baking the mixture. The deepest shade of purple was by far the most precious color, as it was usually obtained from sea whelks.” [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Four Styles of Roman (Pompeian) Painting

Frescoes, murals and paintings in Pompeii are divided into four styles, which roughly match up with four periods, originally defined and described by the German archaeologist August Mau (1840–1909). Mau divided the wall paintings of Pompeii into four styles: first, second, third, and fourth, in chronological order. Fourth style was in vogue when the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius abruptly ended the life of the little city. Pompeii contains one of the largest group of surviving examples of Roman frescoes and wall paintings and it can be presumed the four styles can be applied to some degree to Roman painting in general. [Source: Wikipedia +]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The First Style “was largely an exploration of simulating marble of various colors and types on painted plaster. Artists of the Late Republican period (second to first century B.C.) drew upon examples of early Hellenistic (late fourth to third century B.C.) painting and architecture in order to simulate masonry. Typically, the wall was divided into three horizontal, painted zones crowned with a stucco cornice of dentils based upon the Doric architectural order. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Second Style in Roman wall painting emerged in the early first century B.C., during which time fresco artists imitated architectural forms purely by pictorial means. In place of stucco architectural details, they used flat plaster on which projection and recession were suggested entirely by shading and perspective; as the style progressed, forms grew more complex.

Under Emperor Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) in the second half of the first century B.C., there was a new impulse to innovate, rather than re-create, in architecture, sculpture, and painting. The Third Style (ca. 20 B.C.– 20 A.D.), which coincided with Augustus' reign, rejected illusion in favor of surface ornamentation. Wall paintings from this period typically comprise a single monochrome background—such as red, black, or white—with elaborate architectural and vegetal details. Small figural and landscape scenes appear in the center of the wall as a part of, not the dominant element in, the overall decorative scheme.

Characterized as a baroque reaction to the Third Style's mannerism, the Fourth Style in Roman wall painting (ca. 20–79) is generally less disciplined than its predecessor. It revives large-scale narrative painting and panoramic vistas, while retaining the architectural details of the Third Style. In the Julio-Claudian phase (ca. 20–54), a textilelike quality dominates and tendrils seem to connect all the elements on the wall. The colors warm up once again, and they are used to advantage in the depiction of scenes drawn from mythology.” \^/

See Separate Article: FOUR STYLES OF ANCIENT ROMAN PAINTING europe.factsanddetails.com

Paintings from Pompeii

Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: “ House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto contains some of the finest 'Third Style' wall-paintings yet to be uncovered in Pompeii.Third Style paintings are characterised by ornate frameworks of pseudo-architectural elements, such as columns, which enclose central panel paintings. These central panels often depict mythological scenes, and in this house there are panels illustrating stories such as that of Narcissus, Theseus in the Labyrinth, and the love between Mars and Venus. “The sheer number and quality of the wall-paintings is this house is somewhat unexpected, since the house is of only modest size. [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

One fresco from the Villa of the Mysteries “runs round all four walls of a room....The fresco is a megalographia (a depiction of life-size figures), and is unique in Pompeii. The panels of the fresco appear to show a series of consecutive events, and their interpretation is much debated. Most commonly, it is thought that the fresco illustrates the initiation of a woman into the secret rites of Dionysus, and it is this theory that gave rise to the name of the Villa of the Mysteries. In the scene pictured here, the initiate is flogged, while another woman dances beside her. |::|

“Lararia are shrines to the gods of the household, and are found in different shapes and forms in many Pompeian houses, ranging from simple wall-paintings to large and elaborate shrines. A lararium in the House of the Vetti imitates the form of a temple. Columns support a pediment, and frame a central painting. Two dancing lares (guardians of the family, who protect the household from external threats) hold raised drinking horns. They are positioned on either side of the genius (who represents the spirit of the male head of the household), who is dressed in a toga and making a sacrifice. Beneath them all is a serpent. Snakes are often depicted in lararia, and were considered guardian spirits of the family.”

See Separate Article: PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Painting Found Outside of Pompeii

Campania, the region of Italy around Naples which includes the cities destroyed by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, has few examples of wall art after the A.D. 79 Vesuvius eruption. The murals after that date which have survived come from Rome or the imperial provinces, and they show less taste for fantastic ornamentation and an increase in simpler, more realistic designs, done on white, red, or yellow backgrounds. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

In the Roman province of Britain, a town house of found at Verulamium (modern St. Albans) yields evidence of a mural with painted panels with two candelabra on a red background, and in the center, a blue dove on a perch. On the ceiling, there were ears of wheat painted in a lattice-work design on a purple background. The Romans had a penchant for scenes on a large scale, most of them illustrations of ancient myths. The third century was a period when the Roman Empire seemed on the verge of disintegration, and yet it was also a time when there were new departures in artistic taste. In the eastern provinces, the retreat from naturalism that we find in medieval art, where two-dimensional figures stare directly at the viewer, was already underway.

Some of the earliest Christian art comes from Dura-Europos, a Roman garrison town on the Euphrates River in modern Iraq, and date to the A.D. third century. The wall paintings that were found made art historians rethink their notions about the retreat from naturalism in the late Roman Empire that had hitherto been associated with the rise of Christianity. At one end of the baptistery room in the Dura "house church," set in a vaulted niche, there was a font shaped like a sarcophagus, and on the back wall of the niche was a painting showing Christ as the Good Shepherd, carrying a sheep on his shoulders, and beside him, Adam and Eve. This was clearly an example of wall painting as a mode of instruction: Adam and Eve represented the old Adam who sinned, and Christ, the new Adam, redeemed the victims of original sin. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

Getting Your House Painted in Ancient Rome

Archaeologist Hilary Becker of Binghamton University, who studies ancient pigments, believes that ancient Romans faced the same kind of choices that people today face when it came to painting the inside of their house — namely do they do it themselves and spend more time for a lower quality job or do they hire a professional who can do a more professional job in less time but for a lot more money.

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: No contracts for Roman painting projects survive. But Romans certainly drew up contracts for mosaics and public works, examples of which are extant, and Becker’s work builds on prior scholarship to show that contracts were also struck for house painting. “A client would have chosen all the materials, how many layers of plaster to lay down, the colors, where the paint went on the wall, and the size of images,” Becker says. “Both the client and the painter would have wanted to protect themselves from anything that might cause a dispute. Law underlies so much of Roman life, and these guardrails helped avoid conflicts.” This was especially true when it came to painting because pigments could be extremely pricey and the choice of which to use could dramatically affect a job’s cost. “This all had to be worked out in advance,” Becker says. “The ancient sources tell us that if it was a really expensive pigment like cinnabar, which is mercury sulfide, or the blue copper carbonate mineral azurite, the client had to pay for it themselves.” Copious information about Roman pigments comes from the first-century A.D. naturalist Pliny the Elder, who wrote a great deal about their composition and disapproved of their extravagant use, which, says Becker, he considered evidence of Romans’ profligacy. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2024

A cautionary house-painting tale is shared by the first-century B.C. author Vitruvius, who tells of the folly of Faberius, one of Julius Caesar’s scribes. Faberius had a taste for red and, to paint his colonnaded courtyard on Rome’s Aventine Hill, he went for the more expensive option — cinnabar — over cheaper red ocher. “Faberius would likely have been a freed slave, so this would have been a case of the sort of conspicuous consumption that Pliny the Elder would later deplore,” Becker says. Vitruvius warns that using cinnabar in open spaces where it will be exposed to sunlight or moonlight destroys the color — which is exactly what happened in Faberius’ courtyard. His prized peristyle turned black after just 30 days, “on which account he was obliged to agree with the contractors to lay on other colors,” writes Vitruvius.

While the ancient Romans were clearly devoted to painting their walls, less is known about the process that supplied the vivid colors painters used. In 1974, archaeologists working at the site of Sant’Omobono discovered the only surviving pigment shop from ancient Rome, which dates to the third to early fourth century A.D. While the site was excavated five decades ago, the initial findings are now being reexamined using the latest scientific technology.

Working with chemists including Ruth Beeston of Davidson College and Greg Smith from the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Becker is currently analyzing pigments found in the shop to identify their composition. This might, in turn, help reveal where they came from. “There isn’t any evidence of manufacturing in the shop,” Becker says, “so I’m assuming the pigments were processed elsewhere.”

Thus far, Becker, Beeston, and Smith have identified many shades of red and yellow ocher, an iron-rich pigment called green earth, pink from the madder plant, a calcium carbonate white, and examples of the synthetic pigment known as Egyptian blue created by combining silica, lime, sodium carbonate, and copper. Becker says that their analysis of these pigments has the potential to provide surprising insights into the Roman economy. Being able to pinpoint what type of ocher was being sold, for example, would help establish how far pigments were transported, and studies of minerals sampled at mines might clarify the raw materials’ source. “When you think about color, it’s everywhere,” says Becker. “That’s what’s so exciting about this — it’s a lump of color, but it opens up a whole world.”

Stunning Tomb Paintings of Ichthyocentaurs and Cerberus

In October 2023, archaeologist announced that they had unearthed a 2,200-year-old tomb painted with two uncommon mythical creatures — a pair of ichthyocentaurs, or sea-centaurs, which have the head and torso of a man, the lower body of a horse and the tail of a fish — during an excavation near Naples. The tomb’s hypogeum — a large tomb with chambers or niches for burying several people — was perfect condition, its entrance still covered with tiles. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, October 14, 2023]

The tomb is now known as the Tomb of Cerberus. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: Inside the tomb, numerous frescoes adorn the walls. The two ichthyocentaurs may be depictions of Aphros and Bythos, a pair of mythological sea gods who are the personification of sea foam and the ocean abyss. The sea gods are often shown wearing lobster-claw crowns, but on the wall of this tomb, they are reaching toward each other to hold a large shield known as a clipeus. Two winged, Cupid-like babies complete the scene.The tomb is also covered in painted garlands and features a stunning painting of Cerberus, the mythical three-headed dog who guarded the Roman underworld, who is being captured by the demigod Hercules in the last of his 12 labors. The god Mercury, identifiable by his winged hat, stands nearby.Also included in the tomb are an altar on which family members could leave gifts for the dead, as well as the funeral beds themselves, on which the deceased still rest.

The undisturbed tomb dates to between 194 B.C. and A.D. 27. The discovery was made in the Giugliano region, today a suburb about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) northwest of Naples. Giugliano was one of the smaller inhabited parts of Campania, a fertile region that in ancient times included cities from Capua to Salerno. On what was found in the tomb, Archaeology magazine reported:. Having captured or killed other monstrous beasts, Hercules, with the god Mercury as one of his guides, descended to the underworld to steal Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog, and bring the creature to the surface. Inside the tomb, Simona Formola, head archaeologist of the Archaeological Superintendency for the Metropolitan Area of Naples, found three painted couches, an altar with libation vessels, and the deceased’s remains. “No similar discovery has previously been made in this area, and usually all that is found are modest burials in earthen pits, almost all of which have already been disturbed,” she says. “This discovery is exceptional due to the monumentality of the tomb and its intact state.” [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2024]

According to Live Science later excavations revealed the skeleton of an individual who was covered in a shroud and surrounded by various grave goods, including jars of ointment and a strigil, a Roman personal hygiene tool used to scrape off dirt, perspiration and oil before a person bathed. The deceased, who was in an "excellent state of preservation," according to the Italian Ministry of Culture, had been buried on their back. It appears that the "particular climatic conditions of the funerary chamber" had mineralized the shroud, according to the statement. Ancient pollen samples from the tomb suggest the deceased was treated with creams containing absinthe, as well as Chenopodium, a genus of herbaceous, flowering plants also called goosefoot, according to the statement.[Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 30, 2024]

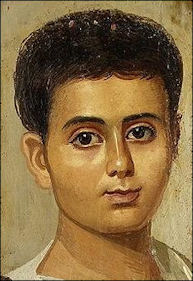

Ancient Roman Mummy Paintings

Some of the greatest Roman-era paintings were produced by Romanized Egyptians, who embalmed their dead, wrapped them as mummies, and painted portraits of the deceased on small wooden panels attached at the head of the shroud wrapped around the mummy wrappings. Sometimes these mummies were put on display before they were buried.

Mummy paintings were rendered from life using colored beeswax on wood panels bounded by linen strips on the outside of the mummy. Pigments mixed with hot wax were used by the Greeks to paint their warships. The Romans used this technique to make portraits on mummy cases in the Fayum region. It is nor clear whether it is the Egyptian influence or the Roman influence that makes the works so exquisite.

About 1,000 Romanized Egyptian mummy portraits have been unearthed at Harawa and Fayum, a fertile basin in the Nile basin. Dating between A.D. 25 and 259 and wonderfully preserved by the dry desert condition, the portraits are often beautiful works of art with shadowing and perspective more advanced than that found in the Middle Ages.

See Separate Article: ROMAN-ERA EGYPTIAN MUMMY PORTRAITS africame.factsanddetails.com

Southern Italian Vase Painting

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “For nearly 300 years, Greek cities along the coasts of southern Italy and Sicily regularly imported their fine ware from Corinth and, later, Athens. By the third quarter of the fifth century B.C., however, they were acquiring red-figured pottery of local manufacture. As many of the craftsmen were trained immigrants from Athens, these early South Italian vases were closely modeled after Attic prototypes in both shape and design. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“By the end of the fifth century B.C., Attic imports ceased as Athens struggled in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War in 404 B.C. The regional schools of South Italian vase painting—Apulian, Lucanian, Campanian, Paestan—flourished between 440 and 300 B.C. In general, the fired clay shows much greater variation in color and texture than that which is found in Attic pottery. A distinct preference for added color, especially white, yellow, and red, is characteristic of South Italian vases in the fourth century B.C. Compositions, especially those on Apulian vases, tend to be grandiose, with statuesque figures shown in several tiers. There is also a fondness for depicting architecture, with the perspective not always successfully rendered. \^/

“Almost from the beginning, South Italian vase painters tended to favor elaborate scenes from daily life, mythology, and Greek theater. Many of the paintings bring to life stage practices and costumes. A particular fondness for the plays of Euripides testifies to the continued popularity of Attic tragedy in the fourth century B.C. in Magna Graecia. In general, the images often show one or two highlights of a play, several of its characters, and often a selection of divinities, some of which may or may not be directly relevant. Some of the liveliest products of South Italian vase painting in the fourth century B.C. are the so-called phlyax vases, which depict comics performing a scene from a phlyax, a type of farce play that developed in southern Italy. These painted scenes bring to life the boisterous characters with grotesque masks and padded costumes.

Five Wares of South Italian Vase Painting

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “South Italian vases are ceramics, mostly decorated in the red-figure technique, that were produced by Greek colonists in southern Italy and Sicily, the region often referred to as Magna Graecia or "Great Greece." Indigenous production of vases in imitation of red-figure wares of the Greek mainland occurred sporadically in the early fifth century B.C. within the region. However, around 440 B.C., a workshop of potters and painters appeared at Metapontum in Lucania and soon after at Tarentum (modern-day Taranto) in Apulia. It is unknown how the technical knowledge for producing these vases traveled to southern Italy.

Theories range from Athenian participation in the founding of the colony of Thurii in 443 B.C. to the emigration of Athenian artisans, perhaps encouraged by the onset of the Peloponnesian War in 431 B.C. The war, which lasted until 404 B.C., and the resulting decline of Athenian vase exports to the west were certainly important factors in the successful continuation of red-figure vase production in Magna Graecia. The manufacture of South Italian vases reached its zenith between 350 and 320 B.C., then gradually tapered off in quality and quantity until just after the close of the fourth century B.C. [Source: Keely Heuer, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

Lucanian crater

“Modern scholars have divided South Italian vases into five wares named after the regions in which they were produced: Lucanian, Apulian, Campanian, Paestan, and Sicilian. South Italian wares, unlike Attic, were not widely exported and seem to have been intended solely for local consumption. Each fabric has its own distinct features, including preferences in shape and decoration that make them identifiable, even when exact provenance is unknown.

Lucanian and Apulian are the oldest wares, established within a generation of each other. Sicilian red-figure vases appeared not long after, just before 400 B.C. By 370 B.C., potters and vase painters migrated from Sicily to both Campania and Paestum, where they founded their respective workshops. It is thought that they left Sicily due to political upheaval. After stability returned to the island around 340 B.C., both Campanian and Paestan vase painters moved to Sicily to revive its pottery industry. Unlike in Athens, almost none of the potters and vase painters in Magna Graecia signed their work, thus the majority of names are modern designations. \^/

“Lucania, corresponding to the "toe" and "instep" of the Italian peninsula, was home to the earliest of the South Italian wares, characterized by the deep red-orange color of its clay. Its most distinctive shape is the nestoris, a deep vessel adopted from a native Messapian shape with upswung side handles sometimes decorated with disks. Initially, Lucanian vase painting very closely resembled contemporary Attic vase painting, as seen on a finely drawn fragmentary skyphos attributed to the Palermo Painter. Favored iconography included pursuit scenes (mortal and divine), scenes of daily life, and images of Dionysos and his adherents.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Five Wares of South Italian Vase Painting by the Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024