Home | Category: Roman Empire and How it Was Built / Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire

TRAJAN’S CONQUEST OF THE DACIANS

Trajan's column

Trajan extended the empire’s reach in Mesopotamia as far as the Persian Gulf, but he’s better remembered for his campaign against the Dacians in present-day Romania, who frequently raided Roman frontier towns. Trajan ended a two-year incursion into Dacia in 103 A.D. by signing a peace treaty with Decebalus, the Dacian king. The Dacians, however, broke the treaty. When Trajan returned to Dacia in 105 A.D. he showed no mercy. [Source: Kristin Baird Rattini, National Geographic History, June 25, 2019]

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “Trajan’s war on the Dacians, a civilization in what is now Romania, was the defining event of his 19-year rule. In back-to-back wars fought between A.D. 101 and 106, the emperor Trajan mustered tens of thousands of Roman troops, crossed the Danube River on two of the longest bridges the ancient world had ever seen, defeated a mighty barbarian empire on its mountainous home turf twice, then systematically wiped it from the face of Europe. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, April 2015 |*|]

“From their powerful realm north of the Danube River, the Dacians regularly raided the Roman Empire. Among Roman politicians, “Dacian” was synonymous with double-dealing. The historian Tacitus called them “a people which never can be trusted.” They were known for squeezing the equivalent of protection money out of the Roman Empire while sending warriors to raid its frontier towns. In A.D. 101 Trajan moved to punish the troublesome Dacians.” He “fortified the border and invaded with tens of thousands of troops. After nearly two years of battle Decebalus, the Dacian king, negotiated a treaty with Trajan, then promptly broke it. Trajan returned in 105 and crushed them. |*|

“Rome had been betrayed one time too many. During the second invasion Trajan didn’t mess around.” On Trajan’s Column, “Just look at the scenes that show the looting of Sarmizegetusa or villages in flames. “The campaigns were dreadful and violent,” says Roberto Meneghini, the Italian archaeologist in charge of excavating Trajan’s Forum. “Look at the Romans fighting with cutoff heads in their mouths. War is war. The Roman legions were known to be quite violent and fierce.” |*|

“In the first major battle Trajan defeated the Dacians at Tapae. A storm indicated to the Romans that the god Jupiter, with his thunderbolts, was on their side. The destruction of Dacia’s holiest temples and altars followed Sarmizegetusa’s fall. “Everything was dismantled by the Romans,” Florea says. “There wasn’t a building remaining in the entire fortress. It was a show of power—we have the means, we have the power, we are the bosses.” The rest of Dacia was devastated too. Near the top of the column is a glimpse of the denouement: a village put to the torch, Dacians fleeing, a province empty of all but cows and goats. |*|

“The two wars must have killed tens of thousands. A contemporary claimed that Trajan took 500,000 prisoners, bringing some 10,000 to Rome to fight in the gladiatorial games that were staged for 123 days in celebration. Dacia’s proud ruler Decebalus, when his capital and all his territory had been occupied and he was himself in danger of being captured, committed suicide, sparing himself the humiliation of surrender. His end is carved on his archrival’s column. Kneeling under an oak tree, he raises a long, curved knife to his own neck. Decebalus’s head was brought to Rome.” the Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote a century later. “In this way Dacia became subject to the Romans.”

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Description of the Trajan Column” by John Hungerford Pollen M.A. Amazon.com;

“Trajan: Rome's Last Conqueror” by Nicholas Jackson (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Danube Frontier: The Danube Frontier (Roman Conquests) by Michael Schmitz (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Dacian War” (Veteran of Rome) by William Kelso (2017) Amazon.com;

“Trajan's Parthian War and Arrian's Parthika” by F.A. Lepper (1985) Amazon.com;

“Trajan: Optimus Princeps” by Julian Bennett (1997) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Later Caesars: The First Part of the Augustan History, with Newly Compiled Lives of Nerva & Trajan” by Anthony Birley (1976) Amazon.com;

“Letters of Pliny” by Pliny the Younger Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C. - A.D. 476" by Michael Grant (1997) Amazon.com;

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World”

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Impact of Trajan’s Conquest of the Dacians

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “Trajan colonized his newest province with Roman war veterans, a legacy reflected in the country’s modern name, Romania. The loot he brought back was staggering. One contemporary chronicler boasted that the conquest yielded a half million pounds of gold and a million pounds of silver, not to mention a fertile new province. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, April 2015 |*|]

“The booty changed the landscape of Rome. To commemorate the victory, Trajan commissioned a forum that included a spacious plaza surrounded by colonnades, two libraries, a grand civic space known as the Basilica Ulpia, and possibly even a temple. The forum was “unique under the heavens,” one early historian enthused, “beggaring description and never again to be imitated by mortal men.” |*|

“Yet once the Dacians were vanquished, they became a favorite theme for Roman sculptors. Trajan’s Forum had dozens of statues of handsome, bearded Dacian warriors, a proud marble army in the very heart of Rome. |*|

Dacians and Sarmizegetusa, Their Political and Spiritual Capital

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “The Dacians had no written language, so what we know about their culture is filtered through Roman sources. Ample evidence suggests that they were a regional power for centuries, raiding and exacting tribute from their neighbors. They were skilled metalworkers, mining and smelting iron and panning for gold to create magnificently ornamented jewelry and weaponry. Dacians fashioned precious metals into jewelry, coins, and art, such as the 17-centimeter-high gold-trimmed silver drinking vessels and 12-centimeter-in-diameter bracelets weighing up to a kilogram. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, April 2015 |*|]

“Sarmizegetusa was their political and spiritual capital. The ruined city lies high in the mountains of central Romania. In Trajan’s day the thousand-mile journey from Rome would have taken a month at least. To get to the site today, visitors have to negotiate a potholed dirt road through the same forbidding valley that Trajan faced. Back then the passes were guarded by elaborate ridgetop fortifications; now only a few peasant huts keep watch. |*|

Trajan column assault on a Roman fort

Sarmizegetusa—a terrace carved out of the mountainside—was the religious heart of the Dacian world. Traces of buildings remain, a mix of original stones and concrete reproductions, the legacy of an aborted communist-era attempt to reconstruct the site. A triple ring of stone pillars outlines a once impressive temple that distantly echoes the round Dacian buildings on Trajan’s Column. Next to it is a low, circular stone altar carved with a sunburst pattern, the sacred center of the Dacian universe.

Gelu Florea, an archaeologist from Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, has spent summers excavating the site. The exposed ruins, along with artifacts recovered from looters, reveal a thriving hub of manufacturing and religious ritual. Florea and his team have found evidence of Roman military know-how and Greek architectural and artistic influences. Using aerial imaging, archaeologists have identified more than 260 man-made terraces, which stretch for nearly three miles along the valley. The entire settlement covered more than 700 acres. “It’s amazing to see how cosmopolitan they were up in the mountains,” says Florea. “It’s the biggest, most representative, most complex settlement in Dacia.”

“There is no sign that the Dacians grew food up here. There are no cultivated fields. Instead archaeologists have found the remains of dense clusters of workshops and houses, along with furnaces for refining iron ore, tons of iron hunks ready for working, and dozens of anvils. It seems the city was a center of metal production, supplying other Dacians with weapons and tools in exchange for gold and grain. |*|

“Not far from the altar rises a small spring that could have provided water for religious rituals. Flecks of natural mica make the dirt paths sparkle in the sun. It’s hard to imagine the ceremonies that took place here—and the terrible end. Florea conjures the smoke and screams, looting and slaughter, suicides and panic depicted on Trajan’s Column. |*|

Trajan’s Column

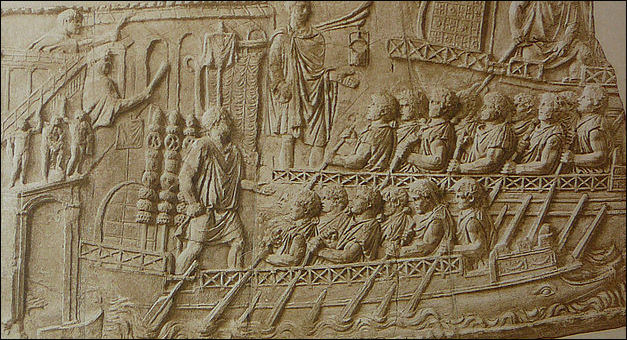

Column of Trajan (at Fori Imperiali) is a 126-five-foot structure with a spiraling scene from Dacian Wars in the Balkans that if unwound would be 656 feet long. Built and inscribed between A.D. 106-113, the column was once topped by a statue of an Trajan, whose ashes and those of his wife are buried underneath its base. Originally it was supposed to be topped by an eagle. The bronze statue of Trajan was destroyed in the Middle Ages. It is now topped by a statue of St. Peter installed by a Renaissance pope. It towers over the ruins of Trajan’s Forum, which once included two libraries and a grand civic space paid for by war spoils from Dacia.

Dr Jon Coulston of the University of St. Andrews wrote for the BBC: “Two monuments bearing sculptures depicting aspects of Trajan's Dacian Wars across the Danube (101 - 102 A.D. and 105- 106 AD) survive: Trajan's Column in Rome (112 AD) and the Trophy of Trajan (Tropaeum Traiani) in south-eastern Romania (108 - 109 AD). The Column depicts a loose narrative of the wars on a 200m-long helical frieze. “The Tropaeum had a frieze of rectangular panels (metopes) each showing two or more figures of Romans and assorted barbarian enemies. Carved locally by legionary troops, these are a valuable foil for the metropolitan sculptures of the Column. [Source: Dr Jon Coulston, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “ Spiraling around the column like a modern-day comic strip is a narrative of the Dacian campaigns: Thousands of intricately carved Romans and Dacians march, build, fight, sail, sneak, negotiate, plead, and perish in 155 scenes. Completed in 113, the column has stood for more than 1,900 years. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, April 2015 |*|]

Trajan Column sacrifices

Today,the eroded carvings are hard to make out above the first few twists of the story. All around are ruins—empty pedestals, cracked flagstones, broken pillars, and shattered sculptures hint at the magnificence of Trajan’s Forum, now fenced off and closed to the public, a testament to past imperial glory. |*|

“The column is one of the most distinctive monumental sculptures to have survived the fall of Rome. For centuries classicists have treated the carvings as a visual history of the wars, with Trajan as the hero and Decebalus, the Dacian king, as his worthy opponent. Archaeologists have scrutinized the scenes to learn about the uniforms, weapons, equipment, and tactics the Roman Army used. |And because Trajan left Dacia in ruins, the column and the remaining sculptures of defeated soldiers that once decorated the forum are treasured today by Romanians as clues to how their Dacian ancestors may have looked and dressed. |*|

“The column was deeply influential, the inspiration for later monuments in Rome and across the empire. Over the centuries, as the city’s landmarks crumbled, the column continued to fascinate and awe. A Renaissance pope replaced the statue of Trajan with one of St. Peter, to sanctify the ancient artifact. Artists lowered themselves in baskets from the top to study it in detail. Later it was a favorite attraction for tourists: Goethe, the German poet, climbed the 185 internal steps in 1787 to “enjoy that incomparable view.” Plaster casts of the column were made starting in the 1500s, and they have preserved details that acid rain and pollution have worn away.” |*|

Meaning and Construction of Trajan’s Column

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “Debate still simmers over the column’s construction, meaning, and most of all, historical accuracy. It sometimes seems as if there are as many interpretations as there are carved figures, and there are 2,662 of those. Travel in time with this stop-motion animation and see how Trajan’s Column was built—according to one theory. How it was made and how accurate it is remain the subjects of spirited debate. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, April 2015 |*|]

Trajan greeted by the barbarians

“Filippo Coarelli, a courtly Italian archaeologist and art historian in his late 70s, literally wrote the book on the subject. In his sun-flooded living room in Rome, he pulls his illustrated history of the column off a crowded bookshelf. “The column is an amazing work,” he says, leafing through black-and-white photos of the carvings, pausing to admire dramatic scenes. “The Dacian women torturing Roman soldiers? The weeping Dacians poisoning themselves to avoid capture? It’s like a TV series.” |*|

“Or, Coarelli says, like Trajan’s memoirs. When it was built, the column stood between the two libraries, which perhaps held the soldier-emperor’s account of the wars. The way Coarelli sees it, the carving resembles a scroll, the likely form of Trajan’s war diary. “The artist—and artists at this time didn’t have the freedom to do what they wanted—must have acted according to Trajan’s will,” he says. Working under the supervision of a maestro, Coarelli says, sculptors followed a plan to create a skyscraping version of Trajan’s scroll on 17 drums of the finest Carrara marble. |*|

“The emperor is the story’s hero. He appears 58 times, depicted as a canny commander, accomplished statesman, and pious ruler. Here he is giving a speech to the troops; there he is thoughtfully conferring with his advisers; over there, presiding over a sacrifice to the gods. “It’s Trajan’s attempt to be not only a man of the army,” Coarelli says, “but also a man of culture.” Of course Coarelli’s speculating. Whatever form they took, Trajan’s memoirs are long gone. In fact clues gleaned from the column and excavations at Sarmizegetusa, the Dacian capital, suggest that the carvings say more about Roman preoccupations than about history. |*|

“Jon Coulston, an expert on Roman iconography, arms, and equipment at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, studied the column up close for months from the scaffolding that surrounded it during restoration work in the 1980s and ’90s. He wrote his doctoral dissertation on the landmark and has remained obsessed—and pugnaciously contrarian—ever since. “People desperately want to compare it to news media and films,” he says. “They’re overinterpreting and always have. It’s all generic. You can’t believe a word of it.” |*|

“Coulston argues that no single mastermind was behind the carvings. Slight differences in style and obvious mistakes, such as windows that disrupt scenes and scenes of inconsistent heights, convinced him that sculptors created the column on the fly, relying on what they’d heard about the wars. “Instead of having what art historians love, which is a great master and creative mind,” he says, “the composition is being done by grunts at the stone face, not on a drawing board in the studio.” |*|

Dacian chiefs

“The artwork, in his view, was more “inspired by” than “based on.” Take the column’s priorities. There’s not much fighting in its depiction of the two wars...The message seems intended for Romans, not the surviving Dacians, most of whom had been sold as slaves. “No Dacians were able to come and see the column,” Meneghini says. “It was for Roman citizens, to show the power of the imperial machinery, capable of conquering such a noble and fierce people.” In other words it can be interpreted as propaganda.

Reading Trajan’s Column

There are 2,662 figures, plus animals, architecture and scenery, in 155 scenes in Trajan's Column. Trajan appears in 58 of them. Viewers were meant to follow the story from bottom to top standing in one place rather than circling the column 23 times, as the frieze does. Key scenes could be seen from two main vantage points. One can also follow the narrative of the epic battle by walking around and around the column like a "circus horse" as one scholar put it. Even though the sculptures made at the top are bigger than those at the bottom, it is still hard to make them out. The figures were originally painted with bright colors and had metal weapons and the horse had metal harness.

The visual narrative that winds from the column’s base to its top depicts Trajan and his soldiers triumph over the Dacians. In one scene Trajan watches a battle, while two Roman auxiliaries present him with severed enemy heads. In another scene Roman soldiers load plunder onto pack animals after defeating Decebalus, the Dacian king.

Breakdown of Activity (by length of scene): 1) Marches (29 percent); 2) Battles (21 percent); 3) Other (12 percent); 4) Construction (12 percent); 5) Negotiations (9 percent); 6) Sacrifices (7 percent); 8) Trajan speeches (6 percent); 9) Events recorded by historians (4 percent). [Source: National Geographic, April 2015]

Trajan’s army included not only professional soldiers but also auxiliaries, conscripts, and mercenaries from across the empire. To reveal more of the warriors, sculptors scaled down some of the shields and cut away Roman helmets. Most of the Dacians are dressed in trousers, tunics, and cloaks, while the Sarmatians, allies of the Dacians, are shown in armor. Dacian helmets appear on the pedestal and column, but only as spoils of war, never on warriors. |*|

reliefs on Trajan's Column

Scenes from Trajan’s Column

The most interesting scene perhaps is the one that shows the Roman army crossing the Danube on a famous bridge.. Other scenes show the army marching into Dacia, the construction of military installations, fighting local barbarians, besieging enemy fortresses, the interrogation of prisoners, the removal of booty, and finally the suicide of the Dacian king, Decebalus, while being pursued by the Roman cavalry, and the capture of his treasure. Dacian prisoners are treated decently after they have been captured, according to the images, while the Roman prisoners of war are tortured by Dacian women. More attention is focused on the logistics of the battle than the actual fighting. The treasure was used to pay for the massive complex with a forum, basilica and libraries that surrounds the column.

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “The column emphasizes Rome’s vast empire. Trajan’s army includes African cavalrymen with dreadlocks, Iberians slinging stones, Levantine archers wearing pointy helmets, and bare-chested Germans in pants, which would have appeared exotic to toga-clad Romans. They’re all fighting the Dacians, suggesting that anyone, no matter how wild their hair or crazy their fashion sense, could become a Roman. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, April 2015 |*|]

“Some scenes remain ambiguous and their interpretations controversial. Are the besieged Dacians reaching for a cup to commit suicide by drinking poison rather than face humiliation at the hands of the conquering Romans? Or are they just thirsty? Are the Dacian nobles gathered around Trajan in scene after scene surrendering or negotiating? |*|

“And what about the shocking depiction of women torturing shirtless, bound captives with flaming torches? Italians see them as captive Romans suffering at the hands of barbarian women. Ernest Oberländer-Târnoveanu, the head of the National History Museum of Romania, begs to differ: “They’re definitely Dacian prisoners being tortured by the angry widows of slain Roman soldiers.” Like much about the column, what you see tends to depend on what you think of the Romans and the Dacians. |*|

“Less than a quarter of the frieze shows battles or sieges, and Trajan himself is never shown in combat...Legionaries—the highly trained backbone of Rome’s war machine—occupy themselves with building forts and bridges, clearing roads, even harvesting crops. The column portrays them as a force of order and civilization, not destruction and conquest. You’d think they were invincible too, since there’s not a single dead Roman soldier on the column.”

Trajan Column voyage

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024