Home | Category: Art and Architecture

FOUR STYLES OF ROMAN (POMPEIAN) PAINTING

Frescoes, murals and paintings in Pompeii are divided into four styles, which roughly match up with four periods, originally defined and described by the German archaeologist August Mau (1840–1909). Mau divided the wall paintings of Pompeii into four styles: first, second, third, and fourth, in chronological order. Fourth style was in vogue when the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius abruptly ended the life of the little city. Pompeii contains one of the largest group of surviving examples of Roman frescoes and wall paintings and it can be presumed the four styles can be applied to some degree to Roman painting in general. [Source: Wikipedia +]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The First Style “was largely an exploration of simulating marble of various colors and types on painted plaster. Artists of the Late Republican period (second to first century B.C.) drew upon examples of early Hellenistic (late fourth to third century B.C.) painting and architecture in order to simulate masonry. Typically, the wall was divided into three horizontal, painted zones crowned with a stucco cornice of dentils based upon the Doric architectural order. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Second Style in Roman wall painting emerged in the early first century B.C., during which time fresco artists imitated architectural forms purely by pictorial means. In place of stucco architectural details, they used flat plaster on which projection and recession were suggested entirely by shading and perspective; as the style progressed, forms grew more complex.

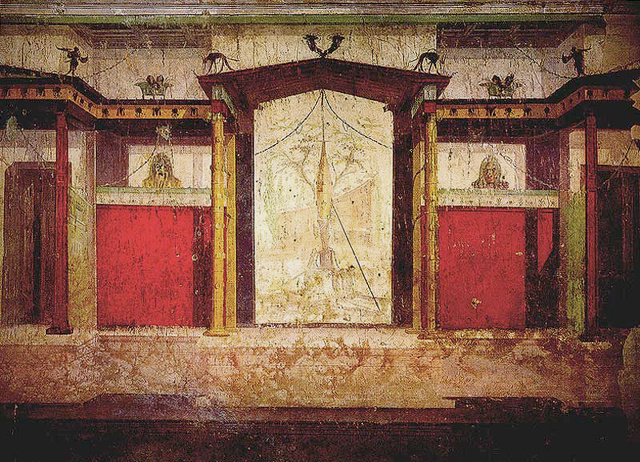

Under Emperor Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) in the second half of the first century B.C., there was a new impulse to innovate, rather than re-create, in architecture, sculpture, and painting. The Third Style (ca. 20 B.C.– 20 A.D.), which coincided with Augustus' reign, rejected illusion in favor of surface ornamentation. Wall paintings from this period typically comprise a single monochrome background—such as red, black, or white—with elaborate architectural and vegetal details. Small figural and landscape scenes appear in the center of the wall as a part of, not the dominant element in, the overall decorative scheme.

Characterized as a baroque reaction to the Third Style's mannerism, the Fourth Style in Roman wall painting (ca. 20–79) is generally less disciplined than its predecessor. It revives large-scale narrative painting and panoramic vistas, while retaining the architectural details of the Third Style. In the Julio-Claudian phase (ca. 20–54), a textilelike quality dominates and tendrils seem to connect all the elements on the wall. The colors warm up once again, and they are used to advantage in the depiction of scenes drawn from mythology.” \^/

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN PAINTING: HISTORY, FRESCOES, TOMBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STUNNING, ROMAN-ERA, FAIYUM MUMMY PORTRAITS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE: HISTORY, TYPES, MATERIALS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MOSAICS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Painting”, Illustrated, by Roger Ling Amazon.com;

“Roman Painting”, lots of images, by Amedeo Maiuri (1953) Amazon.com;

“The Splendor of Roman Wall Painting” by Umberto Pappalardo Amazon.com;

“Domus: Wall Painting in the Roman House” by Donatella Mazzoleni , Umberto Pappalardo, et al. (2005) Amazon.com;

“Painting Pompeii: Painters, Practices, and Organization” by Francesca Bologna (2024) Amazon.com;

“Fausto & Felice Niccolini: Houses and Monuments of Pompeii”

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pompeii”, Illustrated, by Joanne Berry (2007) Amazon.com;

by Valentin Kockel (2016) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Michael Siebler and Norbert Wolf (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Empire: 100-450 AD (Oxford History of Art) by Jaś Elsner Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Paul Zanker (2012) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art: Romulus to Constantine ” by Nancy H. Ramage, Andrew Ramage Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Steven L. Tuck Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Fred Kleiner Amazon.com;

“Art & Archaeology of the Roman World” by Mark Fullerton (2020) Amazon.com

“The Language of Images in Roman Art” by Tonio Hölscher (2004) Amazon.com;

“Power of Images in the Age of Augustus” by Paul Zanker and Alan Shapiro (1988) Amazon.com

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Tradition in Art” by Michael Greenhalgh, (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greece and Rome, From the Rise of Greece to the Fall of Rome”

by Giovanni Becatti (1967) Amazon.com;

First Style of Roman Painting

The First style, also referred to as structural, incrustation or masonry style, was most popular from 200 to 60 B.C. It is characterized by the simulation of marble (marble veneering), with other simulated elements (such as suspended alabaster discs in vertical lines, 'wooden' beams in yellow and 'pillars' and 'cornices' in white), and the use of vivid color, both being a sign of wealth. This style was a replica of that found in the Ptolemaic palaces of the near east, where the walls were inset with real stones and marbles, and also reflects the spread of Hellenistic culture as Rome interacted and conquered other Greek and Hellenistic states in this period. Mural reproductions of Greek paintings are also found. This style divided the wall into various, multi-colored patterns that took the place of extremely expensive cut stone. The First Style was also used with other styles for decorating the lower sections of walls that were not seen as much as the higher levels. The wall painting in the Samnite House in Herculaneum (late 2nd century B.C.) Is a good example of this style. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Philip M. Soergel wrote: First Style tried to produce in painted stucco the appearance of a wall covered with panels of marble or with blocks of masonry, for which reason it is also sometimes called "Masonry Style." The largest house in Pompeii, the House of the Dancing Faun, which was built in the second century B.C., had first-style wall decoration: plaster that faked marble panels, all painted a bright red. Herculaneum has a well-preserved example of this style in a house built in the late second century B.C.: the so-called "Samnite House." The plaster is shaped into panels which were painted using the al fresco technique in which the pigment is applied to the plaster while it is still damp. The inspiration for the style is the marble-paneled walls in the Hellenistic palaces and public buildings in royal capitals such as Alexandria and Antioch. First Style counterfeits the marble panels in plaster, and since the painter had more colors at his command than did the marble-cutter, the effect of First Style could be more garish than the real thing, an example of which can still be seen in the Pantheon in Rome where the marble panels on the wall are still in place. [Source:Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The decline of the First Style coincided with the Roman colonization of Pompeii in 80 B.C., which transformed what had essentially been an Italic town with Greek influences into a Roman city. Going beyond the simple representation of costlier building materials, artists began to borrow from the figural repertoire of Hellenistic wall painting, depicting gods, mortals, and heroes in various contexts. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Second Style of Roman Painting

Second-style painting was illusionist, meaning it tried to create the illusion that the viewer r was looking beyond the confines of the wall to a world outside it of gardens and fantastic architecture. It dominated the 1st century B.C., where walls were decorated with architectural features and trompe l'oeil (trick of the eye) compositions. Early on, elements of this style are reminiscent of the First Style, but this slowly starts to be substituted element by element. [Source: Wikipedia +]

This technique consists of highlighting elements to pass them off as three-dimensional realities – columns for example, dividing the wall-space into zones – and was a method widely used by the Romans. It is characterized by use of relative perspective (not precise linear perspective because this style involves mathematical concepts and scientific proportions like that of the Renaissance) to create trompe l'oeil in wall paintings. The picture plane was pushed farther back into the wall by painted architectonic features such as Ionic columns or stage platforms. These wall paintings counteracted the claustrophobic nature of the small, windowless rooms of Roman houses. A good examples of second-style painting is found in the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus at Pompeii (mid-1st century B.C.). It depicts Cleopatra VII as Venus Genetrix and her son Caesarion as a cupid.

During the reign of Augustus, the style evolved. False architectural elements opened up wide expanses with which to paint artistic compositions. A structure inspired by stage sets developed, whereby one large central tableau is flanked by two smaller ones. In this style, the illusionistic tendency continued, with a 'breaking up' of walls with painted architectural elements or scenes. The landscape elements eventually took over to cover the entire wall, with no framing device, so it looked to the viewer as if he or she was merely looking out of a room onto a real scene. One of the most recognized and unique pieces representing the Second Style is the Dionysiac mystery frieze in the Villa of the Mysteries. This work depicts the Dionysian Cult that was made up of mostly women. In the scene, however, one boy is depicted. +

Philip M. Soergel wrote: Second Style came into fashion after 80 B.C. though it never pushed First Style completely aside. One splendid example was found in the villa of Livia, the wife of the emperor Augustus, at Prima Porta just north of Rome. There a vaulted, partly underground room was painted on all sides with a panorama of a garden, complete with trees bearing fruit and birds. With this illusion the walls of the room no longer confine the space. The artist suggests depth to his painting by a kind of atmospheric perspective: the trees and plants in the foreground are painted precisely but as objects recede into the distance, they become increasingly blurred. If the artist working in Second Style wanted to open up the wall and show landscapes beyond it receding into the distance, he had to use perspective to give depth to his painting. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

Greek scenery designers for the theater had been the first to use perspective in the first half of the fifth century B.C., and its general rules were well known. A fine example of Second Style was found in the villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, otherwise unknown, at Boscoreale near Pompeii which dates to the middle of the first century B.C. The frescoes were removed from the walls and taken to the Metropolitan Museum in New York shortly after the villa was discovered, and they are part of a reconstructed cubiculum, or Roman bedroom, there. The wall paintings create the illusion that the onlooker can walk through the bedroom walls into a cityscape with porticoes, arches, and temples; one view shows a charming tempietto, a small, round shrine which seems to be set in a courtyard surrounded by porticos. Roman taste changed a few years after the villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, as evidenced by the construction of another villa belonging to Agrippa Postumus which was decorated in Third Style about 10 B.C.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Throughout the Villa P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale there are visual ambiguities to tease the eye, painted masonry, pillars, and columns that cast shadows into the viewer's space, and more conventional trompe l'oeil devices. Objects of daily life are depicted in such a way as to seem real, with metal and glass vases on shelves, and tables appearing to project out from the wall. At Boscoreale, the walls dissolve into elaborate displays of illusionist architecture and realms of fantasy. Some of the frescoes provide copies of lost, but presumably once famous, Hellenistic paintings. In the villa's triclinium, painted columns frame a series of figurative paintings presented as if seen through a window in the wall or as if lodged in the architecture. The intention of the owner was to create a kind of picture gallery, with the choice of subjects most likely based on the quality and renown of the original paintings. \^/

Third — Ornate — Style of Roman Painting

The Third style, or ornate style, was popular around 20 - 10 B.C. as a reaction to the austerity of the previous period. It leaves room for more figurative and colorful decoration, with an overall more ornamental feeling, and often presents great finesse in execution. This style is typically noted as simplistically elegant. Its main characteristic was a departure from illusionistic devices, although these (along with figural representation) later crept back into this style. It obeyed strict rules of symmetry dictated by the central element, dividing the wall into 3 horizontal and 3 to 5 vertical zones. The vertical zones would be divided up by geometric motifs or bases, or slender columns of foliage hung around candelabra. Delicate motifs of birds or semi-fantastical animals appeared in the background. Plants and characteristically Egyptian animals were often introduced, part of the Egyptomania in Roman art after Augustus' defeat of Cleopatra and annexation of Egypt in 30 B.C..

Philip M. Soergel wrote: As the landscapes of Second Style went out of fashion, they were replaced by mural designs that emphasized the wall instead of dissolving it into a vista beyond. The artist painted his wall in a solid, dark color such as black, and instead of the architectural elements of Second Style, he framed his space with thin, spidery columns holding up insubstantial canopies — architectural forms that never existed in real life. In the middle of his space he composed a picture enclosed within a frame, like a painting hanging on a wall. Or he sometimes substituted a motif borrowed from Egyptian art. Third Style was elegant and exquisite, but it was also oppressive. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

Examples of this style are best illustrated at the Villa of Livia in Prima Porta outside of Rome (c. 30–20 B.C.) and the Villa of Agrippa Postumus in Boscotrecase (c. 10 BC). According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The finest known achievements of the early Third Style are the frescoes from the Imperial villa at Boscotrecase, where attenuated candelabra and columns support exquisitely rendered vignettes. The early Third Style, which was in effect the court style of Emperor Augustus and his friend Agrippa, eventually gave way to a rekindled interest in elaboration for its own sake.” [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Fourth Style of Roman Painting

The Fourth style — most prominent from A.D. 20 to 79 — is characterized as a baroque reaction to the Third Style's mannerism, It is generally less ornamented but much more complex than the Third style. It revives large-scale narrative painting and panoramic vistas while retaining the architectural details of the Second and First Styles. In the Julio-Claudian phase (c. 20–54 AD), a textile-like quality dominates and tendrils seem to connect all the elements on the wall. The colors warm up once again, and they are used to advantage in the depiction of scenes drawn from mythology. The overall feeling of the walls typically formed a mosaic of framed pictures that took up entire walls. The lower zones of these walls tended to be composed of the First Style. Panels were also used with floral designs on the walls. One of the largest contributions seen in the Fourth Style is the advancement of still life with intense space and light. Shading was very important in the Roman still life. This style was never truly seen again until 17th and 18th centuries with the Dutch. The best example of the Fourth Style is the Ixion Room in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii.

Philip M. Soergel wrote: Illusionism returned with the Fourth Style, which became popular in A.D., when Pompeii was shaken by an earthquake and houses needing their damaged wall paintings restored no doubt opted for the latest style. The emperor Nero, who was building his Domus Aurea (Golden House) in the heart of Rome following the devastation of a great fire that broke out in A.D., used Fourth Style to decorate the rooms of his extravagant new villa. Walls were painted a creamy white with landscapes appearing as framed pictures in the center of a large subdivision of the white wall. There are also architectural vistas, but they are dream cityscapes: columned facades, sometimes fragments of buildings, none of them belonging to the world of reality. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

The painters of these architectural follies may have been influenced by the painted scenery that they saw in contemporary theater. Some of the framed paintings show scenes from mythology: one, from Pompeii, now in the Naples Museum, shows Aeneas, wounded in one leg, being tended by Iapyx, master of the healing art, while Venus appears in the background, bringing with her a medicinal herb. The scene comes from the final book of Virgil's epic, the Aeneid, and it is evidence that the Romans had illustrated books containing such pictures. The codex, or bound book, would not appear until the second century A.D., but the picture of the wounded Aeneas from Pompeii is the sort of illustration that might have been found on a parchment scroll containing the last book of the Aeneid.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024