Home | Category: Etruscans, Pre-Romans and Pre-Republican Rome

ETRUSCAN LIFE

The Etruscans had a thriving society in northern Italy from about 700 B.C. to about 500 B.C., when they began to be absorbed by the Roman Republic. According to Live Science: They developed a unique written language and left behind luxurious family tombs, including one belonging to a prince that was first excavated in 2013. Etruscan society was a theocracy, and their artifacts suggest that religious ritual was a part of daily life. [Source Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 18, 2016]

According to Archaeology magazine: Though a fair amount is known about their wealthy, cosmopolitan culture, nearly all that knowledge comes from the hundreds of tombs that have been found in the land of Etruria, between the Tiber and Arno Rivers, west and south of the Apennine Mountains. These burial chambers, which are often brightly painted and filled with costly grave goods, have provided most of the evidence scholars have used to reconstruct Etruscan customs, cultural connections, and technological achievements. But to this day, their language, despite being written in an alphabet probably related to one of the early Greek alphabets, remains undeciphered, and relatively few Etruscan domestic properties have been identified. Thus many questions about their daily life remain.[Source Archaeology magazine, July-August 2019]

Etruscan statues show people with pointy ears and almond eyes. They wore loose-fitting tunics and reclined on sofas. The Etruscans were also expert horseman and superb oil lamp makers. Soldiers wore shoes made with laces and used bronze weapons. The Etruscan semicircular woolen cloak, draped over one shoulder, is the source of the Roman toga. The Etruscans also introduced the triumphal procession to celebrate military victories and ideas about art, architecture and religion to the Romans.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PRE-ROMAN GROUPS IN ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCANS (800-400 B.C.): HISTORY, ORIGIN AND HOME REGION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN RELIGION: GODS, SACRIFICES, LIVER DIVINATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN BURIALS AND TOMBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN UNDECIPHERED LANGUAGE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN ART: TOMB FRESCOES, GOLD GRAVE GOODS AND BRONZE STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMANS AND ETRUSCANS: INFLUENCES, BATTLES AND LEGENDARY KINGS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Everyday Life of the Etruscans” by Ellen MacNamara (1987) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Dress” by Larissa Bonfante (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan Language: An Introduction” (Revised Editon) by Giuliano Bonfante, Larissa Bonfante Amazon.com;

“Minoan, Etruscan, and Related Languages: A Comparative Analysis”

by Dr. Sergej A. Jatsemirskij , Peggy Duly, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

"Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies” by Larissa Bonfante, Nancy Thomson de Grummond (1986) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans: Italy's Lovers of Life” by Dale Brown (1995) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans” by Graeme Barker, Tom Rasmussen (1998) Amazon.com;

“Central Italy: An Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric, Villanovan, Etruscan, Samnite, Italiote and Roman Remains and the Ancient Road Systems” by R. F. Paget (1973) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History” by Sybille Haynes (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscans: Lost Civilizations” by Lucy Shipley (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan World” (Routledge) by Jean MacIntosh Turfa Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Art (World of Art) by Nigel Jonathan Spivey (1997) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Art: Tarquinia Frescoes” by M. F. Briguet (1962) Amazon.com;

“From the Temple and the Tomb – Etruscan Treasures From Tuscany” by Gregory Warden Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Tomb Paintings, Their Subjects and Significance” (Classic Books) by Frederik Poulsen (1976-1950) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture” by Axel Boethius (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Etruscans” by Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Divine Liver: The Art And Science Of Haruspicy As Practiced By The Etruscans And Romans” by Rev. Robert Lee Ellison (2013) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Myths” by Larissa Bonfante, Judith Swaddling (2006) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Places” by D. H. Lawrence Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan Cities & Rome” by Professor H. H. Scullard (1998) Amazon.com;

Etruscan Houses

Etruscan houses were made from sun-dried mud brick and timber. They also lived in thatch roof huts and tile-roof houses on stone foundations. Their temples had terra-cotta bas-reliefs, tile roofs and decorative friezes.

According to Archaeology magazine: Over several years in the modern village of Vetulonia (the ancient Etruscan settlement of Vetluna), 10 miles northwest of Grosseto, archaeologists from the University of Perugia and the local museum have been excavating a large house. The team’s leader, archaeologist Simona Rafanelli, believes it belonged to a powerful Etruscan family for at least 200 years, until the first quarter of the first century b.c. “This was a rich villa measuring more than 4,300 square feet, with 10 main rooms in addition to other back rooms and servants’ quarters,” says Rafanelli. From at least the third century b.c. on, she explains, was a prosperous time for Vetluna, which enjoyed good relations and a peaceful coexistence with Rome. “This can be seen not only in this house, which we assume was built in this flourishing period,” Rafanelli says, “but also in the expansion of the settlement, as well as in the construction of other rich houses and new decoration of sacred buildings.” [Source Archaeology magazine, July-August 2019]

Unique Etruscan Artifacts and Discoveries

The oldest depiction of childbirth in Western art — a goddess squatting to give birth — was found at the Etruscan sanctuary of Poggio Colla. At the same site, archaeologists found a 4-foot by 2-foot (1.2 by 0.6 meters) sandstone slab containing rare engravings in the Etruscan language. Few examples of written Etruscan survive. Another Etruscan site, Poggio Civitate, was a square complex surrounding a courtyard. It was the largest building in the Mediterranean at its time, said archaeologists who have excavated more than 25,000 artifacts from the site. [Source Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 18, 2016]

The world's oldest false teeth were found in Etruscan tombs dated at 800 B.C. Etruscans dentures were made from ivory, bone and teeth taken from dead people or oxen and held together with gold bridgework. The Etruscans were also regarded as the most skilled dentists in the ancient world.

Archeologist from the University of Florence are excavating a site in Tuscany named Masa Maritima that covered 75 acres and appears to have been a mining town where iron, copper, silver and tin were mined, Controlled by the powerful city of Vetulonia, the town was laid out in a rectangular grid. As of 2010 archeologists had excavated five residential quarters. Many of those houses had sandtstone foundations, walls made of sun-dried bricks and roofs covered with locally-made terra-cotta tiles similar to those still used in Tuscany today. Each quarter contained 10 houses and controlled one mine. There was also an industrial quarter just 30 kilometers from a lake where Etruscans smelted iron. Other ores were taken to different places to refine.

Among the artifacts that have been unearthed in Masa Maritime are vessels, dishes, grindstones, and tools related to wool and textile work, handicrafts usually associated with women. A site called Poggiarello Renzetti has revealed 100 iron nails used to make a second storey of a mud-brick building with a wood and clay upper floor. The house also contains a basement where foodstuffs were stored. .

Archaeology magazine reported: “The excavation of an ancient well in Cetamura del Chianti, Italy, has yielded a veritable treasure trove of information about the site’s Etruscan, Roman, and medieval inhabitants. Over the last four years, archaeologists led by Florida State University’s Nancy de Grummond have retrieved thousands of artifacts spanning 15 centuries — generally well preserved by the watery setting — from the 105-foot-deep well. Many of the objects, including hundreds of votive cups, animal bones, and coins, were intentionally thrown into the well as part of sacred and ritual activity. Among the numerous metal objects recovered are at least 14 bronze Etruscan and Roman water vessels, some finely decorated with mythological creatures. The waterlogged environment also preserved wood and even grape seeds. Researchers are hoping to analyze the seeds’ DNA to further understand the composition of ancient wine, and to match the seeds with modern grape varieties. Says de Grummond, “This rich assemblage of materials in bronze, silver, lead, and iron, along with the abundant ceramics and remarkable evidence of organic remains, creates an unparalleled opportunity for the study of culture, religion, and daily life in Chianti and the surrounding region.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2014]

Etruscan Women and Good Times

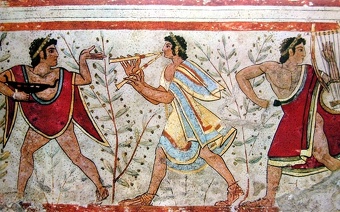

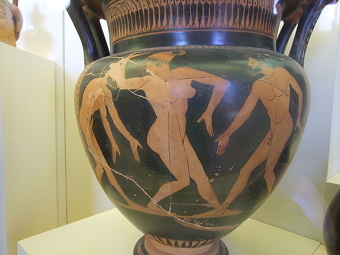

If Etruscan artwork accurately depicts how the Etruscans lived then they were clearly a people who enjoyed. Images in tombs include men using sling shots to hunt birds, naked boys diving, leaping dolphins and dancers strutting their stuff while giving the Texas longhorn hand sign. There are also paintings of lute-like stringed instruments and twin flutes, held in place in a musicians mouth by a leather strap.

Figures of married couples displayed on sarcophagus showed a sensuality and tenderness that was not seen in Greek, Roman or even Renaissance art. Woman and men sat side by side at banquets, a fact that astonished the Romans, who considered the Etruscans hedonists.

Women had higher social status than their counterparts in Greece and Rome. They kept their own names (feminized versions of their father's names) and owned their own property. Tomb pictures depict them partying with males, participating in elaborate dinner parties, attending athletic contests, relaxing on couches and wearing expensive gold jewelry.

Scenes of dancing, feasting and music are found in tomb paintings at Tomba del Triclinio (around 470 B.C.) and Tomba delle Iscrizioni (around 520 B.C.) in Taraquina. The Tomb of the Lioness features two lions and dancers below a checkerboard ceiling.

Work by Southern Methodist University at a site called Poggio Colla indicates that women may have participated in cult activities. A team led by archeologist Gred Warden found a tightly-packed deposit of 18 objects, half of which are gold, and include necklaces, pendants and semiprecious stones. Because they were found outside of tomb and many objects are associated with women the archeologists was surmised they might have been used by women in rituals.

Livy on Etruscan Dancing and Entertainment

The Roman historian Livy wrote in “History of Rome” (A.D. 10): “Book 5.1: “The Veientines, on the other hand, tired of the annual canvassing for office, elected a king. This gave great offence to the Etruscan cantons, owing to their hatred of monarchy and their personal aversion to the one who was elected. He was already obnoxious to the nation through his pride of wealth and overbearing temper, for he had put a violent stop to the festival of the Games, the interruption of which is an act of impiety. The Etruscans as a nation were distinguished above all others by their devotion to religious observances, because they excelled in the knowledge and conduct of them.... [Source: Livy, “The History of Rome, by Titus Livius,” 4 vols., translated by D. Spillan and Cyrus Edmonds (New York: G. Bell & Sons, 1892).

“Book 7.2. But the violence of the epidemic was not alleviated by any aid from either men or gods, and it is asserted that as men's minds were completely overcome by superstitious terrors they introduced, amongst other attempts to placate the wrath of heaven, scenic representations, a novelty to a nation of warriors who had hitherto only had the games of the Circus. They began, however, in a small way, as nearly everything does, and small as they were, they were borrowed from abroad.

The players were sent for from Etruria; there were no words, no mimetic action; they danced to the measures of the flute and practiced graceful movements in Etruscan fashion. Afterwards the young men began to imitate them, exercising their wit on each other in burlesque verses, and suiting their action to their words. This became an established diversion, and was kept up by frequent practice. The Etruscan word for an actor is istrio, and so the native performers were called histriones. These did not, as in former times, throw out rough extempore effusions like the Fescennine verse, but they chanted satyrical verses quite metrically arranged and adapted to the notes of the flute, and these they accompanied with appropriate movements.

“Several years later Livius for the first time abandoned the loose satyrical verses and ventured to compose a play with a coherent plot. Like all his contemporaries, he acted in his own plays, and it is said that when he had worn out his voice by repeated recalls he begged leave to place a second player in front of the flutist to sing the monologue while he did the acting, with all the more energy because his voice no longer embarrassed him. Then the practice commenced of the chanter following the movements of the actors, the dialogue alone being left to their voices. When, by adopting this method in the presentation of pieces, the old farce and loose jesting was given up and the play became a work of art, the young people left the regular acting to the professional players and began to improvise comic verses. These were subsequently known as exodia [after-pieces], and were mostly worked up into the Atellane Plays. These farces were of Oscan origin, and were kept by the young men in their own hands; they would not allow them to be polluted by the regular actors.”

Etruscan Sex Life

The 4th century B.C. Greek historian Theopompus of Chios, wrote a description of the behaviour of Etruscan women. References to this behavior occur also in Plato's ideal State (no. 73) and in Xenophon's description of Sparta (no. 97). Scholars say the account is believed to be inaccurate and the least exaggerated, offering more insight fourth-century Greek attitudes than those of the Etruscans. [Source: Diotima]

Theopompus wrote in “Histories” 115: Sharing wives is an established Etruscan custom. Etruscan women take particular care of their bodies and exercise often, sometimes along with the men, and sometimes by themselves. It is not a disgrace for them to be seen naked. They do not share their couches with their husbands but with the other men who happen to be present, and they propose toasts to anyone they choose. They are expert drinkers and very attractive.

“The Etruscans raise all the children that are born, without knowing who their fathers are. The children live the way their parents live, often attending drinking parties and having sexual relations with all the women. It is no disgrace for them to do anything in the open, or to be seen having it done to them, for they consider it a native custom. So far from thinking it disgraceful, they say when someone ask to see the master of the house, and he is making love, that he is doing so-and-so, calling the indecent action by its name.

“When they are having sexual relations either with courtesans or within their family, they do as follows: after they have stopped drinking and are about to go to bed, while the lamps are still lit, servants bring in courtesans, or boys, or sometimes even their wives. And when they have enjoyed these they bring in boys, and make love to them. They sometimes make love and have intercourse while people are watching them, but most of the time they put screens woven of sticks around the beds, and throw cloths on top of them.

“They are keen on making love to women, but they particularly enjoy boys and youths. The youths in Etruria are very good-looking, because they live in luxury and keep their bodies smooth. In fact all the barbarians in the West use pitch to pull out and shave off the hair on their bodies.

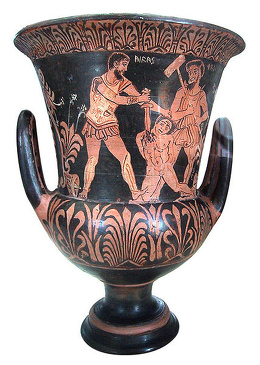

Etruscan Cruelty

Etruscans could also be very cruel. There was a large population of slaves and serfs. They encouraged their pirates to practice cannibalism and tied prisoners face-to-face with corpses. Sometimes slaves and prisoners were sacrificed during the burials of kings.

Etruscan sport could quite violent. One contest illustrated on a tomb wall pitted a blindfolded man with a club against a fierce dog. Some scholars believe the Romans go their ideas for gladiator sports from the Etruscans.

The thumps up, thumbs down signs have been dated back to Etruria in 500 B.C. when the thumbs up sign was a signal to save a fighter’s life in a battle and thumps down meant death. The Romans adopted the same signs for their gladiator battles.

Etruscans Practiced a Unique form of Itinerant Beekeeping

The Etruscans developed a unique system of beekeeping to manufacture honey, beeswax, and other products In July 2017, scientists announced that they discovered 2,500-year-old charred honeycombs, preserved honeybees and honeybee products on the floor of a workshop at an Etruscan trade center in Milan, Italy that showed this. The items included the remains of a unique grapevine honey produced by traveling beekeepers along rivers. “The importance of beekeeping in the ancient world is well known through an abundance of iconographic, literary, archaeometric and ethnographic [or cultural] sources,” Lorenzo Castellano, a graduate student at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University and first author of the new study, told Live Science. “Even so, since honeycombs are perishable, direct fossil evidence of them is “extremely rare,” he added.[Source Rossella Lorenzi, Live Science, July 28, 2017]

In archaeometry, scientists use physical, chemical and mathematical analyses to study archaeological sites. Rossella Lorenzi wrote in Live Science: “Castellano and his colleagues at the University of Milan and the Laboratory of Palynology and Paleoecology of the Institute for the Dynamics of Environmental Processes at Italy’s National Research Council (CNR-IDPA) in Milan found several charred honeycombs, preserved honeybees and honeybee products scattered on the floor of a workshop at the Etruscan trade center of the ancient site of Forcello, near Bagnolo San Vito in the Mantua province.

The building had been destroyed by a fire between 510 and 495 B.C. and was later sealed by a layer of clay so it could be built over. “The findings are therefore preserved in situ, albeit heavily fragmented and often warped by the heat of fire,” Castellano and his team wrote in July in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

“The researchers examined bee-breads (a mixture of pollen and honey), fragments of charred honeycombs, remains of Apis mellifera (honeybees) and a large amount of material resulting from honeycombs that had melted and clumped together. Chemical analysis and an examination of pollen and spores collected at the site confirmed the presence of beeswax and honey on a large portion of the room. Moreover, they found that pollen from a grapevine (Vitis vinifera) abounded in samples from the melted honey and in the honeycomb fragments, indicating the presence of a unique grapevine honey produced from predomesticated or early-domesticated varieties of grapevine.

“Vitis pollen is missing in bee-breads, suggesting that we are dealing with an unprecedented Vitis honey preserved by charcoalification,” the researchers concluded. (Charcoalification, also called carbonization, is a process in which organic carbon substances are converted into a carbon-containing residue.) Today, grapevine honey really has nothing to do with bee-produced honey; it is a kind of syrup produced by boiling grape juice.

“The analyses revealed other unique aspects about the Etruscan beekeeping. Pollen composition showed that honeybees were feeding on plants, including grapevines and fringed water lily, from an aquatic landscape, some of which weren’t known to grow in the area. Such a scenario would have been possible beekeepers who collected bees along a river while aboard a boat, bringing the bees and their hives to workshops to extract the honey and beeswax. Indeed, the finding confirms what Roman scholar Pliny the Elder wrote more than four centuries later about the town of Ostiglia, some 20 miles (32 kilometers) from the site. According to Pliny, the Ostiglia villagers simply placed the hives on boats and carried them 8 kilometers (5 miles) km) upstream at night. “At dawn, the bees come out and feed, returning every day to the boats, which change their position until, when they have sunk low in the water under the mere weight, it is understood that the hives are full, and then they are taken back and the honey is extracted,” Pliny wrote.

“The finding also shows the Etruscans’ high level of specialization in beekeeping.

“It also provides unique information on the ancient Po Plain environment [a geographical feature in northern Italy] and on honeybees’ behavior in a pre-modern landscape,” Castellano and colleagues concluded.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024