Home | Category: Bronze Age Europe / Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory / Etruscans, Pre-Romans and Pre-Republican Rome

PRE-ROMAN GROUPS

Italian groups around in 400 BC Long before Rome was founded, every part of Italy was already peopled. Many of the peoples living there came from the north, around the head of the Adriatic, pushing their way toward the south into different parts of the peninsula. Others came from Greece by way of the sea, settling upon the southern coast. It is of course impossible for us to say precisely how Italy was settled. It is enough for us at present to know that most of the earlier settlers spoke an Indo-European, or Aryan, language, and that when they first appeared in Italy they were scarcely civilized, living upon their flocks and herds and just beginning to cultivate the soil. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Different groups had their own languages, customs and arts. The first evidence of distinct groups is from around 900 B.C.. Between 800 and 400 B.C. some of these groups became powerful enough to form their own city-states. Their language descended from a mother tongue called Sabellic, whose written form was influenced by the Greek, Latin and Etruscan alphabets. Their art, including figures and faces carved from animals bones, was heavily influenced by Greek art. [Source: Erla Zwingle, National Geographic. January 2005]

The largest and most dominate pre-Roman groups, included the Umbrians, who lived north of present-day Perugia and were known as a deeply religious people; the Sabines, whose women were famously raped by followers of Romulus, one of Rome’s founders; Samnites, a fighting people that almost defeated the Romans; and the Faliscans, who chose to be absorbed by the Romans rather than fight them.Other groups included the Marsian people, famed of their snake-handling skills and herbal remedies; and the Piceneians, who lived and the Adriatic and prospered through trade with the Greeks and Phoenicians. Greeks lived in southern Italy and Sicily. Celtic groups such as the Gauls moved into parts of what is now northern Italy.

See Separate Article: ETRUSCANS (800-400 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Italy Before Rome: A Sourcebook" (Routledge) by Katherine McDonald (2021) Amazon.com

“The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium” by Ross R. Holloway (2014) Amazon.com;

“Latium: Prelude to the Roman Kingdom” by Peter Tattersall (2020) Amazon.com;

“Central Italy: An Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric, Villanovan, Etruscan, Samnite, Italiote and Roman Remains and the Ancient Road Systems” by R. F. Paget (1973) Amazon.com;

“Samnium and the Samnites” by E. T. Salmon Amazon.com;

“The Urbanisation of Rome and Latium Vetus: From the Bronze Age to the Archaic Era”

by Francesca Fulminante (2014), ebook Amazon.com;

“Italy Before the Romans: The Iron Age” by David Ridgway Amazon.com

“The Roman Conquest of Italy” by Jean-Michel David and Antonia Nevill (1996)

Amazon.com

“European Societies in the Bronze Age” by A. F. Harding (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age” by Anthony Harding and Harry Fokkens (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Pre-Roman Italy (1000–49 BCE) by Jane Botsford Johnson and Marco Maiuro (2024) Amazon.com;

“Organizing Bronze Age Societies: The Mediterranean, Central Europe, and Scandanavia Compared” by Timothy Earle, Kristian Kristiansen Amazon.com;

“Textile Production in Pre-Roman Italy” by Margarita Gleba (2014) Amazon.com;

“Production, Trade, and Connectivity in Pre-Roman Italy (Routledge) by Jeremy Armstrong and Sheira Cohen (2022) Amazon.com

“The Archaeology of Nuragic Sardinia” by Gary Webster (2016) Amazon.com;

“Sicily Before History: An Archeological Survey from the Paleolithic to the Iron Age” by Robert Leighton (1999) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Ceramic Fabrics 2: Italy: Southern Tyrrhenian. Neolithic – Bronze Age”

by Sara T. Levi, Valentina Cannavò, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide” by Amanda Claridge (1998) Amazon.com

“Art & Archaeology of the Roman World” by Mark Fullerton (2020) Amazon.com

“Roman Archaeology for Historians” by Ray Laurence (2012) Amazon.com

Latium — the Area Around Rome — Before the Romans

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: It is not before the beginning of the first millennium B.C. (between the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age) that it becomes possible to identify traits of a Latin material culture attesting to an ethnogenesis in the plain south of the lower course of the Tiber, a territory that was bordered on the northwest by the Tiber and the hills north of it, and on the northeast by the (later) Sabine mountainous area. On the east this area was bound by the Alban chain from the mountains of Palombara, Tivoli (Tibur), Palestrina (Praeneste), and Cori (Cora) as far as Terracina (Anxur) and Circeo (Circei), and to the west was the shore of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Small settlements formed in this area within a population that was melted together from (probably) local people and immigrants from the north and northeast. Scholars know nothing of their religion apart from the tombs attesting inhumation, as well as cremation. At Rome traces of earlier presences of humans have been found, but continuous settlements on places like the Palatine started around the tenth century. From around 830 B.C. onward, smaller settlements took shape at privileged places of the plain, a proto-urban phase. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

It is possible to give some detail of the conditions of life in these population centers. They drew their sustenance mainly from animal husbandry and from the exploitation of natural resources (salt, fruit, and game). Their inhabitants progressively took up agriculture in pace with the clearing of the woods and the draining of the marshes, at the same time making pottery and iron tools. Their language belonged to the Indo-European family. The first document in the Latin language may be an inscription on a golden brooch from Praeneste, dated to the end of the seventh century: "manios med fhefhaked numasioi" Manius made me for Numerius"). However, the authenticity of this inscription is doubtful.

The placing and the contents of tombs attest to growing social differentiation and the formation of gentilician groups; urns in the form of oblong huts are characteristic. At Osteria dell'Osa of the ninth century, cremation served as a social marker that separated outstanding male warriors — recognizable by miniature weapons — from the rest of the population.

Social differentiation was certainly furthered by the presence of Greeks in Italy from 770 B.C. onward who could serve as traders and agents in long-distance contacts with the southern and eastern part of the Mediterranean. The Orientalizing period (c. 730–630 B.C.) is present in the form of luxury tombs, princely burials with highly valuable and prestigious objects in sites around Rome), though not in Rome itself. Social power offered the possibility of acquiring wealth and long-distance contacts; such contacts and goods served to further prestige.

DNA Evidence on the Origin of the Romans and People in Italy

A 2019 genetic study published in the journal Science analyzed the autosomal DNA of 11 Iron Age samples from the areas around Rome, concluding that Etruscans (900-600 BC) and the Latins (900-200 BC) from Latium vetus were genetically similar, and Etruscans also had Steppe-related ancestry despite speaking a pre-Indo-European language. [Source Wikipedia]

A 2021 genetic study published in the journal Science Advances analyzed the autosomal DNA of 48 Iron Age individuals from Tuscany and Lazio and confirmed that the Etruscan individuals displayed the ancestral component Steppe in the same percentages as found in the previously analyzed Iron Age Latins, and that the Etruscans' DNA completely lacks a signal of recent admixture with Anatolia or the Eastern Mediterranean, concluding that the Etruscans were autochthonous and they had a genetic profile similar to their Latin neighbors. Both Etruscans and Latins joined firmly the European cluster, 75 percent of the Etruscan male individuals were found to belong to haplogroup R1b, especially R1b-P312 and its derivative R1b-L2 whose direct ancestor is R1b-U152, while the most common mitochondrial DNA haplogroup among the Etruscans was H.

Early People in Italy and Ideas About Progress and Civilization

Neolithic pottery fragment from Sicily

David Silverman of Reed College wrote:“The single, central, and most important lesson to take away from these remarks on Neolithic and Chalkolithic inhabitants of the Italian peninsula is this, that in antiquity broadly speaking advances in culture, what one might call the progress of civilization, moves inexorably from the east to the west. Throughout the period any comparison between even the most advanced of the civilizations in peninsular Italy and those living further to the east, whether Greeks, Sumerians, Akkadians, Hittites, or Egyptians, will make the Italians look fairly backward. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“What does it mean to speak of the progress of civilization or advanced civilizations of the ancient world? One could turn to certain objective criteria: the use of letters and literacy, the ability to build large impressive buildings, the tendency to coalesce into more densely populates areas, walled towns or cities. One could point out that the earliest Roman literary works we know of, the epics of Naevius and Ennius, were fully five hundred years later than Homer. This way of thinking is tempting because there is a real element of truth in it. The fact is that with the exceptions of civilizations which suffered some major setback, such as an invasion or a natural disaster, the pattern was that as time went by people wrote more, read more, built more impressive buildings, became increasingly urbanized. ^*^

“This way of thinking about progress and comparing different ancient civilizations is also quite dangerous. It makes and rests upon a series of assumptions, assumptions which passed unchallenged in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when classical scholarship and classicism were coming into their own, but which have sat less comfortably with some in our own time. For example, it is only in the last thirty years, building on the pioneering work of Milman Parry on the Homeric epics, that a full appreciation of the potential of an oral poetic tradition for detail and artistry has come into the mainstream. Is a highly literate culture necessarily better or more advanced that one which relies on a vigorous oral tradition, or just different (and so no less deserving of being studied)? Wherein should we find the innate superiority of a city to a scattered group of villages housing the same number of people? Do not more "advanced" societies also produce a more pronounced disparity between the social and economic classes, as against the more cooperative and egalitarian model of so-called "primitive" villages?”

Indo-Europeans

Around a 3000 B.C., during the early Bronze Age, Indo-European people began migrating into Europe, Iran and India and mixed with local people who eventually adopted their language. In Greece, these people were divided into fledgling city states from which the Mycenaeans and later the Greeks evolved. These Indo European people are believed to have been relatives of the Aryans, who migrated or invaded India and Asia Minor. The Hittites, and later the Greeks, Romans, Celts and nearly all Europeans and North Americans descended from Indo-European people.

Indo-Europeans is the general name for the people speaking Indo-European languages. They are the linguistic descendants of the people of the Yamnaya culture (c.3600-2300 B.C. in Ukraine and southern Russia who settled in the area from Western Europe to India in various migrations in the third, second, and early first millenniums B.C.. They are the ancestors of Persians, pre-Homeric Greeks, Teutons and Celts. [Source: Livius.com]

Indo-European intrusions into Iran and Asia Minor (Anatolia, Turkey) began about 3000 B.C.. The Indo-European tribes originated in the great central Eurasian Plains and spread into the Danube River valley possibly as early as 4500 B.C., where they may have been the destroyers of the Vinca Culture. Iranian tribes entered the plateau which now bears their name in the middle around 2500 B.C. and reached the Zagros Mountains which border Mesopotamia to the east by about 2250 B.C...

See Separate Article INDO-EUROPEANS factsanddetails.com

Indo-Europeans in Italy

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “All of the languages spoken in prehistoric Italy, with the exception of Etruscan, are members of the Indo-European language family. Working backwards on the basis of similarities among words from different languages and dialects (the comparative method), scholars are able to reconstruct the bare bones of a language they call Proto-Indo-European (PIE). The people who spoke this language were on the move in the latter part of the third and the first half of the second millennia BC. These people, these speakers of PIE, come to us loaded with ideological signification. They are wrapped in the now discredited racist efforts of the Nazis and other groups who sought to make them the archetypal civilizers, the so-called Aryan people from whose bloodline the pure stock of Germany was supposed to descend. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Hence, when we find that leading scholars such as Massimo Pallottino, the dean of Italic prehistory, are more than a little wary about admitting to a massive influx of more advanced PIE-speaking people across the Alps in the Early to Middle Italic Bronze Age, we may suspect that (even if unconsciously) there is more involved in the decision than an impartial assessment of the evidence. Whenever the evidence can bear it, in fact, Pallottino and his school tend to favor a hypothesis of native development to explain and account for major innovations traceable in the archaeological record, as opposed to the influx of new and ethnically different kinds of people. Of course, even Pallottino, with his nativist bent, admits that prior to the Early Bronze Age the people of Italy were in all probability not speaking a dialect of Indo-European, and that the Indo-European language must have come into Italy from outside. ^*^

The standard line posits a single large ingression of warlike Indo-European speakers, who both tamed and advanced the indigenous population, and whose language and cultural practices spread throughout the peninsula. Pallottino prefers a messier model. He argues that the various Italic dialects, Latin, Osco-Umbrian, and the rest, can not be direct descendants of a single Proto-Italic dialect of PIE. In other words, that Indo-European was introduced into Italy at various times and in various guises, by various different groups of people, who were not conquerors en masse but rather smaller groups who were peacefully absorbed into the existing culture. Burial practice is extremely important for deciding on this question.” ^

Invasion and Native Hypotheses on the Early Inhabitants of Italy

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The standard line goes something like this. The shift from inhumation to cremation happens earlier, around a hundred or a hundred and fifty years earlier, among the Terramare people than among the Apennine people. The shift is accompanied by other cultural changes of the type already mentioned: new pottery, better metalworking, more settled agriculture in place of nomadic pastoralism. Moreover, at this same time and for a hundred years earlier, we have these large sites in central Europe, e.g. in Germany and Hungary, where the exact same kind of cremation and inhumation in urns was being practiced (the settlements of the Urnfield cultures). Accordingly, the standard line once again sees a massive influx of cremating, Indo-European speaking people across the Alps from the Danube River valley area around 1400 BC. These people mixed with and took over the Terramare culture. Then, some time later, the southward move continued. The Appenine people started cremating and burying the ashes in urns, and this must therefore be the result of southward movement by the newly augmented Terramaricoli. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Over the last twenty years, the challenge to this hypothesis has been vigorous. Some scholars, such as Pallottino, believe that the earliest examples of cremation in prehistoric Italy are found among the Appenine people. If this were true, it would give the lie to the invasion hypothesis, since the invaders would encounter the Terramaricoli in the north, in the Po valley, long before the Appenine people further south. So Pallottino again thinks in terms of numerous and scattered contacts with more advanced peoples, and especially prefers to look to the east for these rather than to the north. However, he and his supporters are able to cite only a single site (Canosa) where there is a cremation alleged to be dated by the associated pottery to around 1400. The fact is that the bulk of the cremations among the Appenine peoples are considerably later. And the coincidence between the central European Urnfields and the Middle Bronze Age Italic burial practice is impossible to dismiss. We can admit the possibility of increasing influence from contacts across the Adriatic and from points further east (e.g. involving the mysterious "sea people" referred to in contemporary Egyptian documents), as Pallottino wishes, but some form of the invasion hypothesis looks to be correct. ^*^

“With the cataclysmic end of the Mycenaean civilization in Greece around 1150-1100 BC, mirrored in the Mycenaean settlements all over the Mediterranean, contact between the Greeks and the Italians comes to a near total halt. It would remain so for 400 years. Next time, we will start to find out what the Italians were up to in their absence.” ^*^

Neolithic and Bronze Age People in Italy

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “It is important to understand that terms such as Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age translate into hard dates only with reference to a particular region or peoples. In other words, it makes sense to say that the Greek Bronze Age begins before the Italian Bronze Age. Classifying people according to the stage which they have reached in working with and making tools from hard substances such as stone or metal turns out to be a convenient rubric for antiquity. Of course it is not always the case that every Iron Age people is more than advanced in respects other than metalworking (such as letters or governmental structures) than the Bronze Age folk who preceded them. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“If you read in the literature on Italian prehistory, you find that there is a profusion of terms to designate chronological phases: Middle Bronze Age, Late Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age I, Middle Bronze Age II, and so forth. It can be bewildering, and it is damnably difficult to pin these phases to absolute dates. The reason is not hard to discover: when you are dealing with prehistory, all dates are relative rather than absolute. Pottery does not come out of the ground stamped 1400 BC. The chart on the screen, synthesized from various sources, represents a consensus of sorts and can serve us as a working model. ^*^

“It first became clear in 1943-1945, from aerial photos taken for military purposes, that there had been prehistoric habitation in Italy in the Tavoliere (Northern Apulia). Since then a much fuller picture of Prehistoric Italy has emerged. The essential characteristics of the Neolithic settlements indicate that the people led similar lives to those of the Neolithic people in Greece and elsewhere in Europe. The main type of dwelling was a circular hut, with a sunken floor, a central hearth for both heating and cooking, and a smoke-hole in the top of the wattle-and-daub roof. The people lacked any sort of metal tools and did not practice weaving; their knives and axes were of stone and their clothing consisted of animal skins. Their primary means of subsistence was foraging and hunting. Like their counterparts in other parts of Europe, they carved in stone, and their carvings include a high proportion of the "steatopygous" female type.

See Separate Article: LATE STONE AGE AND BRONZE AGE ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com

Terramare and Appennine People

During the Middle Bronze Age, farmers belonging to a culture known as the Terramare settled the Po Plain, which is bordered by the Alps to the north and west, the Apennine Mountains to the south, and the Adriatic Sea to the east.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The Middle Bronze Age is characterized by the flourishing of two distinct groups, the Terramare people or Terramaricoli (dwellers on land and sea) in the Po valley, and the Appenine people on either side of the ridge of the Appenine mountains in central and southern Italy. The break with the Early Bronze rests upon new pottery types, new kinds of settlements, increased skill in metalworking, and a shift towards settled agriculture from semi-nomadic pastoralism. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Because the Terramare people seemed to lay their villages out in grid systems, and favored the digging of deep ditches around their settlements, some romance minded early Italian archaeologists thought of them as Proto-Romans (because Roman colonies and military camps were laid out on a grid and surrounded by a ditch and a palisade). The outstanding characteristic of their towns, from which their name derives, is that they built their huts upon piles or terraces on the banks of rivers. But the fact is, of course, that the later pattern of Roman towns and camps had nothing to do with how these prehistoric people lived. It is with these people, though. that the debate between the proponents of the invasion or immigration pattern and those who favor the local development model heats up. The standard line holds that the Terramare people are immigrants from the Danube River valley area, and that they are speakers of a dialect of Indo-European.

“More widespread than the Terramaricoli, the Apennine people are usually depicted as being just a few steps behind them, although ahead of many of their countrymen, who continued to live as Neolithic people in blissful ignorance of the progress being made elsewhere on their peninsula. Essentially pastoralists, they would graze their animals in the hills during the warm season and move down to the plains in the winter. They had extensive contacts with the Mycenaean traders during the years that those traders were active on the mainland (c. 1350-1150), especially through their settlement near the Mycenaean trading post at Scoglio del Tonno (Tarentum).

“Up until around 1400 BC, or the start of Middle Bronze Age II, both types of Bronze Age Italians had practiced inhumation, the burial of dead bodies in caves or in the ground, exclusively. Suddenly (in archaeological terms, i.e. over a transitional period of perhaps 50 years) they begin cremating the dead and interring their ashes in special containers, earthenware burial urns. Basic anthropology teaches us that disposal of the dead tends to be a deeply rooted custom, of long standing and significance, because many peoples of the world have believed that how the dead are buried will affect their experience in the afterlife and/or the relations between themselves and the ghosts of their ancestors. In other words, people do not just change their custom in the disposal of the dead for no reason.

See Separate Article: ARCHAEOLOGY RELATED TO PRE-ROMAN ITALY AND LEGENDARY PERIOD ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Villanovans

Villanovans were early Etruscans who inhabited central Italy. The Villanovan culture (c. 900–700 B.C.) is considered as the earliest phase of the Etruscan civilization and was the earliest Iron Age culture of Italy. It developed from the Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture which in turn branched off from the Urnfield culture of Central Europe. The name come from the locality of Villanova, part of Metropolitan City of Bologna where Giovanni Gozzadini found the remains of a necropolis, excavating 193 tombs, of which 179 were cremations and 14 inhumations, between 1853 and 1855. [Source Wikipedia]

The Villanovans buried the ashes of their dead in pottery urns of distinctive double-cone shape.Of the 193 tombs, six were separated from the rest as if to signify a special social status. The "well tomb" pit graves lined with stones contained funerary urns. These had been only sporadically plundered and most were untouched. In 1893, a chance discovery unearthed another distinctive Villanovan necropolis at Verucchio overlooking the Adriatic coastal plain.

Villanovan carried out some trade in some trading metal in return for other goods. Archaeology magazine reported: A small site on the rocky island of Tavolara off the coast of Sardinia may reveal a robust trading relationship between two Iron Age cultures. In the ninth century B.C., the Nuragic people of the main island of Sardinia exchanged ceramic and metal artifacts with the Villanovans, early Etruscans who inhabited central Italy. Although brooches and other Villanovan metal objects have been unearthed occasionally on Sardinia, evidence of exchange between the cultures has come primarily from Nuragic artifacts found in the tombs of high-status Villanovans in northern Etruria. As a result, scholars think that the Nuragic people and Villanovans mostly interacted on the mainland. [Source: Benjamin Leonard March/April 2021

On a Tavolara beach, however, a team led by Italian archaeologist Paola Mancini recently unearthed the first Villanovan ceramics ever found on Sardinia. Because the researchers have identified no traces of residences there, they believe the site functioned as a kind of trading post. Archaeologist Silvia Amicone of the University of Tübingen carried out scientific analysis of reddish coarseware jars from the site. Her results indicate that the utilitarian vessels originated from different production centers in northern and southern Etruria. According to the researchers, their findings confirm that the Villanovans crossed the Tyrrhenian Sea to visit Sardinia.

Villanovans and Iron Age Italy

Villanovan culture around 900 BC

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The Iron Age in Greece comes in with a bang, with the catastrophic destruction of the Mycenaean palatial civilization; in Italy the Iron Age comes in with a whimper, as the Late Bronze Age (where we left off in the previous lecture) just fades into the Early Iron Age. The time frame for this transition coincides with the first century or two of the new millennium, 1000-900 B.C. For a long time it was fashionable and customary to call all or almost all of the Early Iron Age people Villanovans, after a culture whose material remains are known from a site called Villanova, in the Po valley near Bologna. In one sense this was valid. The people at Villanova were just one of many settlements of a group who represented some of the first iron workers in Italy; the distinctive features of their culture include cremation of the dead and burial in biconical urns. Their main settlements were in the area west of the Rome-to-Rimini line. The problem was that as more and more sites were excavated, including especially those of the late Bronze Age, more and more features of the "Villanovan" culture kept turning up. The interpretation of this new evidence tended to take the form of a debate over the question of at what date the Villanovan culture began; and the date kept getting pushed back. At length it became clear that there was, fundamentally, cultural continuity between the Terramare and Apennine peoples of the Late Bronze Age and the "Villanovans." So the former group is styled "proto-Villanovans" and our ability to refer to the latter group as Villanovans is preserved. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Even with that cleared up, the Villanovans remain problematic. Some scholars feel that the differences between late Bronze Age and Villanovan culture are great enough that the Villanovans must have come in from outside of Italy, and some put upon them the onus of having introduced Indo-European to Italy. Some again regard the Villanovans as an ethnically distinct group; but more now would say that is impossible, and regard them as essentially an indigenous group influenced by developments to the north and east. One approach (which you see in Carey and Scullard) relies on a division between northern and southern Villanovans, the latter group being distinguished by the use of burial urns in the shape of huts. In any case, we will look at the Villanovans as they appear primarily in two different locations, in Latium and in Etruria. If we admit that there is essential continuity between Villanovans and what succeeds them in these places, distinctions among different kinds of Villanovans come to seem less useful. ^*^

“Of the situation elsewhere in Italy in the years 1000-800 B.C. , in the east and in the south, there is little to say. The material remains are plentiful enough but it is almost impossible to trace the process by which the different regions took on their ethnic characteristics, except by recklessly projecting back from much later mythologies and nomenclatures. One anchor in that sea may be the Iapygians, who pretty clearly push in around this time from Illyria.” ^*^

Italic Tribes

Italic tribes south of Rome

The Italic people is a linguistic designation. It refers to the Osco-Umbrians and Latino-Faliscans, speakers of the Italic languages, a subgroup of the Indo-European language family. These groups tended to live in temporary settlements rather than towns; farmed small plots and herded cattle and sheep; traded with foreign merchants such as the Greeks and Phoenicians; fought periodically with neighboring groups; and practiced local religions that revolved around trinities of gods, animal sacrifices and looking for omens in everything from bird flight patterns to sheep entrails.

We may for convenience group the Italic tribes into four divisions the Latins, the Oscans, the Sabellians, and the Umbrians. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

1) The Latins dwelt in central Italy, just south of the Tiber. They lived in villages scattered about Latium, tilling their fields and tending their flocks. The village was a collection of straw-thatched huts; it generally grew up about a hill, which was fortified, and to which the villagers could retreat in times of danger. Many of these Latin villages or hill-towns grew into cities, which were united into a league for mutual protection, and bound together by a common worship (of Jupiter Latiaris); and an annual festival which they celebrated on the Alban Mount, near which was situated Alba Longa, their chief city. \~\

2) The Oscans were the remnants of an early Italic people which inhabited the country stretching southward from Latium, along the western coast. In their customs they were like the Latins, although perhaps not so far advanced. Some authors include in this branch the Aequians, the Hernicans, and the Volscians, who carried on many wars with Rome in early times. \~\

3) The Sabellians embraced the most numerous and warlike peoples of the Italic stock. They lived to the east and south of the Latins and Oscans, extending along the ridges and slopes of the Apennines. They were devoted not so much to farming as to the tending of flocks and herds. They lived also by plundering their neighbors’ harvests and carrying off their neighbors’ cattle. They were broken up into a great number of tribes, the most noted of which were the Samnites, a hardy race which became the great rival of the Roman people for the possession of central Italy. Some of the Samnite people in very early times moved from then mountain home and settled in the fertile plain of Campania. \~\

4) The Umbrians lived to the north of the Sabellians. They are said to have been the oldest people of Italy. But when the Romans came into contact with them, they had become crowded into a comparatively small territory, and were easily conquered. They were broken up into small tribes, living in hill-towns and villages, and these were often united into loose confederacies. \~\

Influences of Different Pre-Roman Groups

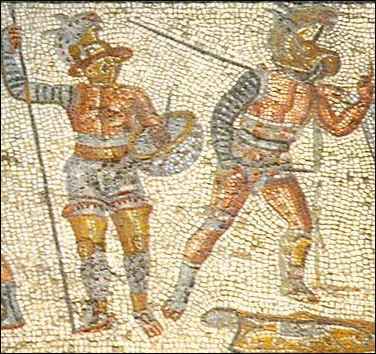

Samnite gladiators, inspired by the Samnite Italic group The Roman custom of giving first and last names came from the Sabines. Gladiator contests evolved out Etruscan funeral rituals. The seven vowel sounds of ancient languages like Umbrian remain alive in Italian even though there are only five vowels in the Latin alphabet. The name “Italy” is derived from an ancient Sabellic word that was originally only used to describe the southern toe of the peninsula.

Several Italic cultures adopted birds such as woodpeckers and ducks as their totems. The Umbrians looked for good and bad omens in the flight patters of birds and their respect towards birds remains alive in avian family names such as Passeri (sparrows), Fagiani (pheasants) and Galli (roosters).

One Italian scholar told National Geographic, “The regionalism that is still so strong today in Italy originally stems from the difference between all these groups. They are lots of cultural roots. Groups that existed in pre-Roman times such as the Sardinians, Corsicans, Ligurians, Venetians, and Umbrians tend to identify themselves by their ancient group first and as Italians second. Italy was fragmented before the Roman Empire and afterwards and did not unify into Italy until the 19th century.

Inter-Cultural ‘Party’ with Minoans and Mycenaeans in Southern Italy?

The Bronze Age site of Roca in Southern Italy has produced archaeological evidence of “one of the earliest inter-cultural feasting parties’ in Mediterranean Europe, dating to c.a. 1200 B.C. . Dr. Francesco Iacono wrote in pasthorizonspr.com: “This small (about 3 hectares nowadays, although it was larger in the past) but monumental fortified settlement (its stone walls measured up to 25m in width), located on the Adriatic coast of Apulia, southern Italy, has been investigated for many years by a team from the University of Salento. Such a research has demonstrated the existence of a long-lasting and intense relationship with Minoan and Mycenaean Greece at least from c.a. 1400 B.C. and of more sporadic connections since the earliest Bronze Age occupation at the site. One of the areas of the settlement (investigated a few years ago) has produced the largest set of ceramics of Mycenaean type ever found in the same context west of Greece (more than 380 vessels). This pottery was associated with abundant local ceramics, remains of meals and of numerous animal sacrifices. A recent study suggests this was the result of a large-scale feast in which it is possible to recognise the participation of groups of people with two distinct cultural backgrounds. [Source: Francesco Iacono, pasthorizonspr.com, December 2015, Iacono is a specialist in Mediterranean prehistory and is a postdoctoral fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge.

Villanovan hut-shaped urn

“One is the southern Italian component, hinted by the local ceramic material as well as by the very modality of the sacrifices. Analyses of bones have shown that after the killings, extensive portions (e.g. one entire leg, or the head) were separated from the carcasses and deposited in the ground and covered up with leaves and branches that left impressions on the back of the thick crushed limestone pavement that sealed all this. Such a ritual procedure seems not to be attested in the Mycenaean world, where animal sacrifices normally involve the use of fire, but finds some parallels in other Bronze Age sites in Southern Italy.

“The second cultural component was the Aegean one, broadly intended, and this is suggested by the copious presence of Aegean style pottery (both imported and locally made) as well as by the very nature of the feast. Evidence for large feasting events involving the presence of a considerable number of people at the same time (the count of participants estimated on the basis of the consumption of the meat of the sacrificed animals alone was between 530 and 176 people) is lacking in Italian Bronze Age, but these events were relatively common in the Aegean world. Also, the probable use of alcoholic drinks (suggested by the recovery of both Aegean style wine cups and large transport stirrup jars, the ancestors of classical amphorae) is an element that is not present in southern Italy but widespread in the Minoan/Mycenaean world, where this was an important part of Palatial societies.

“The broad context in which this event took place provides clues on some of the possible reasons behind it. In the Late Bronze Age, after the fall of Mycenaean palaces, the links between Italy (including the north of the peninsula, rich in metal resources) and the societies that continued to inhabit the Aegean, had increased considerably. East-west connections did not affect only the central Mediterranean region as indeed at the same time many ‘western looking’ artefacts (both ceramics and metal types) started to appear in main sites in Greece.

“Being located at the junction between the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea, Roca acquired a considerable importance in these connections, acting as a mediating node. The feasting practices demonstrated at Roca give us a first concrete snapshot of the details of what these encounters between people possibly coming from distant locales might have looked like."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guidesand various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2024