Home | Category: Etruscans, Pre-Romans and Pre-Republican Rome

ETRUSCAN LANGUAGE

The Etruscan language is almost unique among European languages — nearly all of which (including English) are derived from Indo-European tongues that arrived in Europe thousands of years ago. Etruscan, however, is an outlier — a rare case of a language that predated and survived the Indo-European influx. The Roman emperor Claudius (r. 41–54 A.D.) was a student of Etruscan, and one of the last people in classical antiquity able to speak and read it. Claudius even wrote a 20-volume history of the Etruscans, a work that has not survived to the modern age. [Source Marina Escolano-Poveda, National Geographic History, May 20, 2022]

Theresa Huntsman of Washington University in St. Louis wrote: “ There are no known parent languages to Etruscan, nor are there any modern descendants, as Latin gradually replaced it, along with other Italic languages, as the Romans gradually took control of the Italian peninsula. The Roman emperor Claudius [Source: Theresa Huntsman, Washington University in St. Louis, "Etruscan Language and Inscriptions", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

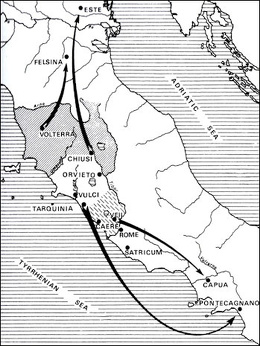

The Etruscans had a written languages but only fragments have been discovered. It was unlike any other language and to this day it remains undeciphered. In 1885 a stele carrying an inscription in a pre-Greek language was found on the island of Lemnos, and dated to about the 6th century B.C. Philologists agree that this has many similarities with the Etruscan language both in its form and structure and its vocabulary. In 1964, archaeologists found three Rosseta-stone-like gold sheets with Etruscan writing and Phoenician writing in Pygi, Italy. The texts were determined to related to rituals but they failed to add much to the understanding of the Etruscan language. As of 2010, about 300 Etruscan words were known.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PRE-ROMAN GROUPS IN ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCANS (800-400 B.C.): HISTORY, ORIGIN AND HOME REGION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN RELIGION: GODS, SACRIFICES, LIVER DIVINATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN BURIALS AND TOMBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN LIFE: SEX, BEES, CRUELTY, GOOD TIMES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN ART: TOMB FRESCOES, GOLD GRAVE GOODS AND BRONZE STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMANS AND ETRUSCANS: INFLUENCES, BATTLES AND LEGENDARY KINGS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Etruscan Language: An Introduction” (Revised Editon) by Giuliano Bonfante, Larissa Bonfante Amazon.com;

“Minoan, Etruscan, and Related Languages: A Comparative Analysis”

by Dr. Sergej A. Jatsemirskij , Peggy Duly, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

"Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies” by Larissa Bonfante, Nancy Thomson de Grummond (1986) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans: Italy's Lovers of Life” by Dale Brown (1995) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans” by Graeme Barker, Tom Rasmussen (1998) Amazon.com;

“Central Italy: An Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric, Villanovan, Etruscan, Samnite, Italiote and Roman Remains and the Ancient Road Systems” by R. F. Paget (1973) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History” by Sybille Haynes (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscans: Lost Civilizations” by Lucy Shipley (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan World” (Routledge) by Jean MacIntosh Turfa Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Art (World of Art) by Nigel Jonathan Spivey (1997) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Art: Tarquinia Frescoes” by M. F. Briguet (1962) Amazon.com;

“From the Temple and the Tomb – Etruscan Treasures From Tuscany” by Gregory Warden Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Tomb Paintings, Their Subjects and Significance” (Classic Books) by Frederik Poulsen (1976-1950) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture” by Axel Boethius (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Etruscans” by Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Divine Liver: The Art And Science Of Haruspicy As Practiced By The Etruscans And Romans” by Rev. Robert Lee Ellison (2013) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life of the Etruscans” by Ellen MacNamara (1987) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Dress” by Larissa Bonfante (2003) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Myths” by Larissa Bonfante, Judith Swaddling (2006) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Places” by D. H. Lawrence Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan Cities & Rome” by Professor H. H. Scullard (1998) Amazon.com;

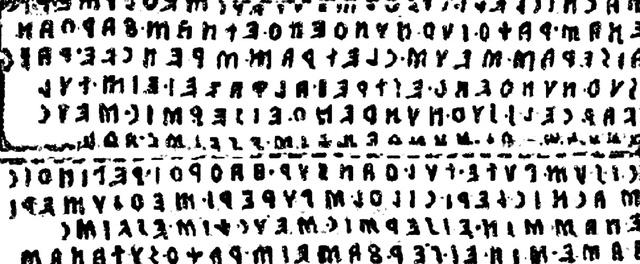

Etruscan Writing

Theresa Huntsman of Washington University in St. Louis wrote: “Etruscan did not appear in written form until the seventh century B.C., after contact with Euboean Greek traders and colonists, and it is the Euboean Greek alphabet that the Etruscans adopted and adapted to fulfill the phonological and grammatical needs of their native tongue. The Etruscans wrote right to left, and many of the Greek letters are reversed in orientation. Some early Greek inscriptions are also written from right to left, or in a continuous string of lines running first right to left, then left to right. [Source: Theresa Huntsman, Washington University in St. Louis, "Etruscan Language and Inscriptions", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

“We have no surviving histories or literature in Etruscan, and the only extant writing that can be considered a text, as opposed to an inscription, was painted in ink on linen, preserved through the fortuitous reuse of the linen as wrappings for an Egyptian mummy now in Zagreb. The existence of such objects like an Etruscan abecedarium in the form of an inkwell, as well as artistic representations of books or scrolls, confirms a written tradition on perishable materials. Despite the lack of preserved texts, the corpus of more than 10,000 Etruscan inscriptions on local and imported goods for daily, religious, and funerary use give us insight into the importance of language in Etruscan life and afterlife. \^/

The Phoenician alphabet was a forerunner of the Etruscan, Latin, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac scripts. Etruscan writing in turn influenced the Greek and Latin (Roman) alphabets. Denise Schmandt-Besserat of the University of Texas wrote: “Because the alphabet was invented only once, all the many alphabets of the world, including Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, Amharic, Brahmani and Cyrillic, derive from Proto-Sinaitic. The Latin alphabet used in the western world is the direct descendant of the Etruscan alphabet (Bonfante 2002). The Etruscans, who occupied the present province of Tuscany in Italy, adopted the Greek alphabet, slightly modifying the shape of letters. In turn, the Etruscan alphabet became that of the Romans, when Rome conquered Etruria in the first century BC. The alphabet followed the Roman armies. All the nations that fell under the rule of the Roman Empire became literate in the first centuries of our era. This was the case for the Gauls, Angles, Saxons, Franks and Germans who inhabited present-day France, England and Germany. [Source: Denise Schmandt-Besserat, Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, January 23, 2014]

Etruscan Inscriptions

Theresa Huntsman of Washington University in St. Louis wrote: “Etruscan inscriptions fulfilled a number of roles, and they often reveal the intended purposes of the objects that bore them. The writing system developed out of necessity when the Etruscans began to engage in Mediterranean trade, and inscriptions could address practical concerns, such as the price of an object, or indicate a buyer’s or seller’s mark. [Source:Theresa Huntsman, Washington University in St. Louis, "Etruscan Language and Inscriptions", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

"There is an overwhelming number of “speaking” objects, or vessels inscribed with phrases to express ownership or dedication, written as if the object itself were speaking. For example, an Italo-Corinthian alabastron in the collection is incised with the phrase “mi licinesi mulu hirsunaiesi,” or “I am the gift of Licinius Hirsunaie.” This could indicate that the vessel was intended as an offering to a deity, but it could also illustrate a gift exchange between wealthy individuals.

“Inscriptions associated with pictorial scenes, such as tomb paintings, painted vases, or engraved mirrors, help us to understand what the scene represents. The Etruscans celebrated Greek myths and worshipped many of the same deities, but with variations in the conventions used to portray the narratives that can make them difficult to interpret. Engraved bronze mirrors from numerous Etruscan tombs bear intricate, rich, and nuanced mythological scenes that can be fully understood only through the carefully inscribed names that identify each of the figures . In fact, the only way we know the Etruscan names for the gods is through these labeled mythological scenes on objects and in tomb paintings. Some names are “Etruscanized” versions of the Greek names, e.g., Aplu for the Greek Apollo or Ercle for the Greek Herakles, but others are entirely different and only identifiable through illustrated, labeled scenes, e.g., Tinia for Zeus or Turan for Aphrodite. \^/

“Etruscan tombs, in both their construction and contents, prove that the Etruscans conceived of the afterlife as an extension of actual life. The tomb often replicates a domestic interior, filled with all the objects the deceased would need, like personal adornments, games, banqueting wares, and even food. Inscriptions played a key role in the afterlife, too. Etruscan sarcophagi and cremation urns bore the full names of their owners, often identifying the names of the individual’s father, mother, and for women, her husband. Relatives entering a family tomb to bury an individual would be able to identify the effigies of their ancestors. Inscriptions also had the power to transform objects from things for the living to things for the dead. Through the act of inscribing the word suthina, meaning “for the tomb,” pottery, jewelry, and metal objects such as weapons, armor, mirrors, and vessels were thereby “transformed” and designated for use by the deceased in the afterlife. Some objects were probably made or purchased expressly for burial and inscribed during or shortly after production. Others, however, may have been personal possessions that were inscribed upon the individual’s death and burial.” \^/

Efforts to Decipher the Etruscan Language

The Etruscan language is still undeciphered. About 10,000 Etruscans inscriptions have been found, most of them are tomb inscriptions related to funerals or dedicated to gods. They can be "read" in the sense that scholar can make out the specific letters, derived from Greek, but apart from about a few hundred names for places and gods they can not figure out what the inscriptions say.

Etruscan presents an unusual decipherment challenge in that "the script is known, but not the language," James Allen, an Egyptology professor at Brown University, told Live Science. "Examples are Etruscan, which uses the Latin alphabet, and Meroitic, which uses a script derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs. In this case, we can read the words, but we don't know what they mean." (The Meroitics lived in northern Africa.) [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 14, 2021]

Etruscan Language Still Mostly Undeciphered Despite Promising Find

Cippus Perusinus, a stone tablet bearing 46 lines of incised Etruscan text, 3rd or 2nd century BC; it is one of the longest extant Etruscan inscriptions

Rossella Lorenzi wrote in Archaeology magazine: An inscribed stone slab unearthed at an Etruscan site in Tuscany is proving to contain one of the most difficult texts to decipher. It was believed that the sixth-century B.C. stela would shed light on the still-mysterious Etruscan language, but so far it remains a puzzle. “To be honest, I’m not yet sure what type of text was incised on the stela,” says Rex Wallace, professor of classics at the University of Massachusetts. Inscribed with vertical dots and at least 70 legible letters, the four-foot-tall and two-foot-wide slab had been buried for more than 2,500 years in the foundations of a monumental temple at Poggio Colla, some 22 miles northeast of Florence in the Mugello Valley. [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2016]

Archaeologists speculate that the text, written right to left, may refer to a goddess who was worshiped at the site, but so far no name of any god or goddess has been found. “The inscription is divided into words by means of three vertically aligned dots, so it’s possible to identify some of the word forms in the text,” Wallace says. “Unfortunately, most of the words that have been identified, apart from the numeral ki, ‘three,’ appear to be new additions to the Etruscan lexicon and we can’t yet pinpoint the meanings,” he adds.

“One of antiquity’s great enigmas, the Etruscans began to flourish around 900 B.C., and dominated much of Italy for five centuries. By around 300 to 100 B.C., they were absorbed into the Roman Empire. Their non-Indo-European language eventually died out, and much of what we know comes from short funerary inscriptions. “Now we are adding another example to the inventory of texts that aren’t short and formulaic,” Wallace explains. “However, this means it will be very difficult to interpret, for that very reason.”

Egyptian Mummy Wrapped in Linen Covered with Etruscan Writing

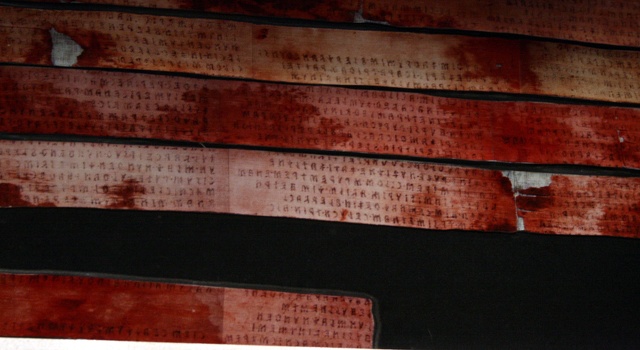

Marina Escolano-Poveda wrote in National Geographic History: In 1868 the Museum of Zagreb in Croatia acquired an Egyptian mummy of a woman. Her previous owner had removed her wrappings but held on to them. She had been an ordinary person in here 30s or 40s,, not royalty or of the priestly class. Her wrappings, however, held a fascinating puzzle — writing that decades later was determined to be Etruscan.[Source Marina Escolano-Poveda, National Geographic History, May 20, 2022]

The discovery was sensational. References to Etruscan linen books can be found in many classical works, but surviving specimens had been impossible to find. The arid climate of Egypt coupled with the desiccants used to dry out the mummy had created a perfect environment to preserve the fragile textile. The mummy’s wrappings were not only the first linen Etruscan text found intact but also the longest text ever found in Etruscan.

The writing on the mummy's linen is now known as Linen Book of Zagreb. In addition to the Etruscan text, the her mummy was laid to rest with a necklace of colored beads, a flower headdress, and a mummified cat’s skull. Scholars still don’t know exactly how this Etruscan text ended up in Egypt. Several hypotheses have been put forward. One is that the city of Alexandria, where the mummy was purchased in the 19th century, was a focus of international trade between the fourth and the first centuries B.C. In a cosmopolitan port city, texts from other cultures would not have been a rarity; her body was simply mummified with the material available at the time. According to this theory, there is no special link between the book itself and the beliefs of the dead woman. The mummifiers just used what was around.

Another theory takes a radically different view, pointing to Etruscan statuary that depicts linen books being placed in tombs, much as Egyptians placed the Book of the Dead in theirs. If the dead woman was of Etruscan ancestry, her relatives might have buried her according to the customs of both her adoptive and ancestral cultures, using both the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the Etruscan linen text.

What the Etruscan Writing on the Mummy Says

Marina Escolano-Poveda wrote in National Geographic History: Before being torn into bandages, the Linen Book of Zagreb was a sheet about 11 feet long covered with 12 columns of text. The part recovered from the bandages is thought to correspond to about 1,330 words— about 60 percent of the original text. Prior to the linen book’s discovery, Etruscan experts had only been able to study the ancient language based on some 10,000 short inscriptions. The linen book on the mummy greatly increased the amount of available text. [Source Marina Escolano-Poveda, National Geographic History, May 20, 2022]

The experts translating the Linen Book of Zagreb needed profound knowledge of the Etruscan calendar and gods. The following examples are taken from the first lines of the book’s eighth column:

θucte. ciś. śariś. esvita. vacltnam

“On [August] 13, conduct the consecration according to the rite.”

culścva. spetri. etnam. i.c. esvitle. ampn/ eri

“Keep/Guard the doors [open?] then, for the consecration.”

celi. huθiś. zaθrumiś. flerχva. neθunsl śucri. θezeric.

“On September 24th, sacrificial victims for Nethuns [Neptune] are to be presented.”

The Etruscan linen book was not the only text that formed part of the mummy’s wrappings. A papyrus of the Egyptian Book of the Dead was also used to wrap the body. This Egyptian work references a female figure, named Nesi-Khons (“the mistress of the house”), whom scholars now believe to be the woman whose body was mummified. In the late 20th century, it was established that she lived sometime between the fourth and the first centuries B.C. and died in her 30s.

The linen book’s black ink was made from burnt ivory, with titles and rubrics in red written in cinnabar, a scarlet ore used in pigments. The Etruscan text was obscured in many places by the balsam used in the mummification process, but in the 1930s, advances in infrared photography allowed 90 more lines of the Etruscan to be deciphered, further clarifying what scholars believed the book’s role had been: a ritual calendar detailing rites enacted throughout the year.

The instructions in the Etruscan book center on when certain gods should be worshipped and what rites, such as a ritual libation or animal sacrifice, should be performed. Among the specific deities mentioned is Nethuns, an Etruscan water god, a figure closely related to the Roman sea god, Neptune. The text also references Usil, the Etruscan sun god, similar to Helios, the Greek solar god.

Further study identified words and names that pinpoint the place of its composition. Etruscan experts believe the linen book was made near the modern-day Italian city of Perugia. While the linen itself has been dated to the fourth century B.C., textual clues place the writing to much later. The inclusion of the month of January as the start of the ritual year is the strongest indicator that the text was written sometime between 200 and 150 B.C. If this later dating of the text is correct, it opens a window onto a way of life that was soon to be swept away by the expansion of Roman power.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024