Home | Category: Etruscans, Pre-Romans and Pre-Republican Rome

ETRUSCANS

The Etruscans were a mysterious people who resided in a region in east-central Italy slightly north of present-day Rome. They created the first great civilization in what is now Italy, centered in Latium and Tuscany, but left behind a sparse written record so little is known about them except what can be surmised from the pottery and artwork left behind in tombs and the observations of Roman historians. [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, June 1988; Dora Jane Hamblin, Smithsonian; Rossella Lorenz, Archaeology, November/December 2010]

The Etruscans were a mysterious people who resided in a region in east-central Italy slightly north of present-day Rome. They created the first great civilization in what is now Italy, centered in Latium and Tuscany, but left behind a sparse written record so little is known about them except what can be surmised from the pottery and artwork left behind in tombs and the observations of Roman historians. [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, June 1988; Dora Jane Hamblin, Smithsonian; Rossella Lorenz, Archaeology, November/December 2010]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The Etruscans are known to most people as the northern neighbors of the ancient Romans (the Latins). The civilization reached its zenith around 750 B.C., when a confederation made up of Etruria, the Po Valley, the Alps, and Campania, in southern Italy worked in mutual cooperation. Trade with the Celts in modern France and Greeks of the Peloponnese spread Etruscan culture into northern Europe and around the Mediterranean. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 13, 2022]

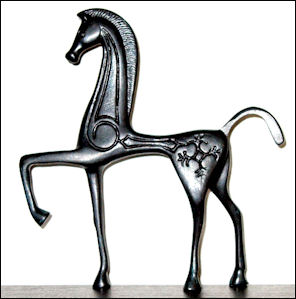

The Etruscans began as a loose confederation of towns as early 3000 years ago in Etruria, a land between the Tiber and Arno rivers mostly in what is now Tuscany and the area north of Rome, and flourished between 700 and 500 B.C. when they were assimilated into the Romans. Masters of metallurgy and skilled seamen, the Etruscans founded a culture that was very advanced and quite different from other known Italian cultures that flourished at the same time, and highly influential in the development of Roman civilization. At a time when the Romans were just peasant villagers the Etruscans were living in luxurious houses and inscribing documents and filling tombs with gold and silver and imported treasures.

The Etruscans were an agricultural civilization with developed metallurgy that was organized into city-states. They built the first cities in Italy. The Etruscan's have been recognized more for their artistry than their fighting skills. In his misleading portrait of the Etruscans D.H. Lawrence wrote: "How much more Etruscan than Roman the Italy of today is: sensitive, diffident, craving really for symbols and mysteries, able to be delighted with true light over small things, violent spasms, and altogether without sternness or natural will-to-power."

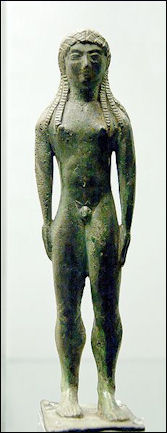

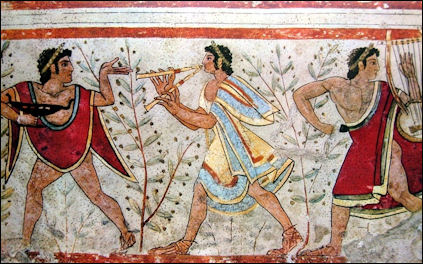

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Etruscans were an ancient Italic culture linguistically identifiable by about 700 B.C. Their culture developed from a prehistoric civilization known as Villanovan (ca. 900–500 B.C.). By the beginning of the seventh century B.C., the Etruscans occupied the central region of Italy between the Arno and Tiber rivers, and eventually settled as far north as the Po River valley and as far south as Campania. They flourished until the end of the second century B.C., when they were fully subsumed into Roman culture. While some 13,000 Etruscan texts exist, most of these are very short. Consequently, much of what we know about the Etruscans comes not from historical evidence, but from their art and the archaeological record. Many Etruscan sites, primarily cemeteries and sanctuaries, have been excavated, notably at Veii, Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Vulci, and Vetulonia. Numerous Etruscan tomb paintings portray in vivid color many different scenes of life, death, and myth. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

RELATED ARTICLES:

PRE-ROMAN GROUPS IN ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN RELIGION: GODS, SACRIFICES, LIVER DIVINATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN BURIALS AND TOMBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN UNDECIPHERED LANGUAGE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN LIFE: SEX, BEES, CRUELTY, GOOD TIMES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ETRUSCAN ART: TOMB FRESCOES, GOLD GRAVE GOODS AND BRONZE STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMANS AND ETRUSCANS: INFLUENCES, BATTLES AND LEGENDARY KINGS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies” by Larissa Bonfante, Nancy Thomson de Grummond (1986) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans: Italy's Lovers of Life” by Dale Brown (1995) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans” by Graeme Barker, Tom Rasmussen (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Pre-Roman Italy (1000–49 BCE) by Jane Botsford Johnson and Marco Maiuro (2024) Amazon.com;

“Central Italy: An Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric, Villanovan, Etruscan, Samnite, Italiote and Roman Remains and the Ancient Road Systems” by R. F. Paget (1973) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History” by Sybille Haynes (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscans: Lost Civilizations” by Lucy Shipley (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan World” (Routledge) by Jean MacIntosh Turfa Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Art (World of Art) by Nigel Jonathan Spivey (1997) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Art: Tarquinia Frescoes” by M. F. Briguet (1962) Amazon.com;

“From the Temple and the Tomb – Etruscan Treasures From Tuscany” by Gregory Warden Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Tomb Paintings, Their Subjects and Significance” (Classic Books) by Frederik Poulsen (1976-1950) Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan Language: An Introduction” (Revised Editon) by Giuliano Bonfante, Larissa Bonfante Amazon.com;

“Minoan, Etruscan, and Related Languages: A Comparative Analysis”

by Dr. Sergej A. Jatsemirskij , Peggy Duly, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Etruscans” by Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Divine Liver: The Art And Science Of Haruspicy As Practiced By The Etruscans And Romans” by Rev. Robert Lee Ellison (2013) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life of the Etruscans” by Ellen MacNamara (1987) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Dress” by Larissa Bonfante (2003) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Myths” by Larissa Bonfante, Judith Swaddling (2006) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Places” by D. H. Lawrence Amazon.com;

“The Etruscan Cities & Rome” by Professor H. H. Scullard (1998) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture” by Axel Boethius (1985) Amazon.com;

Influence and Mystery of the Etruscans (800-400 B.C.)

The Etruscans, who dwelt primarily northwest of Latium, in many respects were the most remarkable people of early Italy. In early times they were a powerful nation, stretching from the Po to the Tiber, and having possessions even in the plains of Campania. They were great builders, constructing massive walls, durable roads, well-constructed sewers, and imposing sepulchers. Their cities were fortified, often in the strongest manner, and also linked together in confederations. Their prosperity was founded not only upon agriculture, but also upon commerce. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

The Etruscans, who dwelt primarily northwest of Latium, in many respects were the most remarkable people of early Italy. In early times they were a powerful nation, stretching from the Po to the Tiber, and having possessions even in the plains of Campania. They were great builders, constructing massive walls, durable roads, well-constructed sewers, and imposing sepulchers. Their cities were fortified, often in the strongest manner, and also linked together in confederations. Their prosperity was founded not only upon agriculture, but also upon commerce. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Rossella Lorenzi wrote in Discovery News: “The Etruscans have long been considered one of antiquity’s greatest enigmas.A fun-loving and eclectic people who among other things taught the French how to make wine, the Romans how to build roads, and introduced the art of writing to Europe, the Etruscans began to flourish in Etruria (an area in central Italy area that covered now are Tuscany, Latium, Emilia-Romagna and Umbria) around 900 B.C., and then dominated much of the country for five centuries. Known for their art, agriculture, fine metalworking and commerce, they started to decline during the fifth century B.C., as the Romans grew in power. By 300-100 B.C., they eventually became absorbed into the Roman empire.Their puzzling, non-Indo-European language was virtually extinguished and they left no literature to document their society. Indeed, much of what we know about them comes from their cemeteries: only the richly decorated tombs they left behind have provided clues to fully reconstruct their history. [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, Discovery News, September 19, 2012]

Rossella Lorenz wrote in Archaeology, “They taught the French to make wine and the Romans to build roads, and they introduced writing to Europe, but the Etruscans have long been considered one of antiquity’s great enigmas. No one knew exactly where they came from. Their language was alien to their neighbors. Their religion included the practice of divination, performed by priests who examined animals’ entrails to predict the future. Much of our knowledge about Etruscan civilization comes from ancient literary sources and from tomb excavations, many of which were carried out decades ago. But all across Italy, archaeologists are now creating a much richer picture of Etruscan social structure, trade relationships, economy, daily lives, religion, and language than has ever been possible. Excavations at sites including the first monumental tomb to be explored in over two decades, a rural sanctuary filled with gold artifacts, the only Etruscan house with intact walls and construction materials still preserved, and an entire seventh-century B.C. miner’s town, are revealing that the Etruscans left behind more than enough evidence to show that perhaps, they aren’t such a mystery after all. [Source: Rossella Lorenz, Archaeology, November/December 2010]

History of Etruscans

The history of the Etruscans extends before the Iron Age to the end of the Roman Republic or from 1200 B.C . to 100 B.C. Many archaeological sites of the major Etruscan cities were continuously occupied since the Iron Age, and the people who lived in the Etruria region did not appear suddenly, nor did they suddenly start to speak Etruscan. Rather they learned to write from their Greek neighbours and thus revealed their language.The Etruscans first appeared in the historical record around 800 to 750 B.C. There were different from other Italic groups in that spoke a different language. No one knows where they came from and exactly when they arrived. They most likely evolved from Iron Age farmers that already lived in central Italy . Many of their settlements were set up on sites previously occupied the Villanovan culture.

The history of the Etruscans extends before the Iron Age to the end of the Roman Republic or from 1200 B.C . to 100 B.C. Many archaeological sites of the major Etruscan cities were continuously occupied since the Iron Age, and the people who lived in the Etruria region did not appear suddenly, nor did they suddenly start to speak Etruscan. Rather they learned to write from their Greek neighbours and thus revealed their language.The Etruscans first appeared in the historical record around 800 to 750 B.C. There were different from other Italic groups in that spoke a different language. No one knows where they came from and exactly when they arrived. They most likely evolved from Iron Age farmers that already lived in central Italy . Many of their settlements were set up on sites previously occupied the Villanovan culture.

See Villanovans under PRE-ROMAN GROUPS IN ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com

Etruscans city- states stretched from Bologna to the Bay of Naples. Around 650 B.C., they were already dominant in the region and took control of Rome, wanting its strategic position on the Tiber. David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “When first we encounter them in Roman history, the Etruscans are a culturally and ethnically distinct group living in a well-defined region. Modern Tuscany has natural borders, with the Arno and the Tiber rivers to the north and south, the Apennine mountains to the east. The area was sparsely inhabited in the early and middle Bronze Age, and as elsewhere on the peninsula the Iron Age came in slowly, with much bronzework continuing to be done. The culture of the inhabitants of Etruria begins to distinguish itself markedly from the rest of Italy in the second half of 8th century, around the same time as cultural influences from Greece and Phoenicia are being felt throughout the region. To what extent this is a coincidence is disputed. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“What is clear is that the Etruscans had a high culture from the 7th century onwards; it went together with an empire of sorts, attested by Etruscan colonies or trading posts, such as Capua in Campania. Neighboring Latium in this period was within the Etruscan sphere of influence, but in the 5th century the Romans began a series of wars with their neighbours, including the Etruscans, in which the Romans eventually prevailed. Etruscan culture continues to show strongly independent features in the 4th century B.C., but gradually thereafter they become merged with the other peoples of Italy and Rome, such that by the time of the transition from Republic to Empire they no longer constitute a distinctive group.” ^*^

The Etruscans lived on the fringes of the Greek world. Like the ancient Greeks, who prospered about the same time, the Etruscans were organized into independent city states. The large number of Etruscan words borrowed by the Greeks indicates the two civilizatios had been in contact with one another for a considerable amount of time.

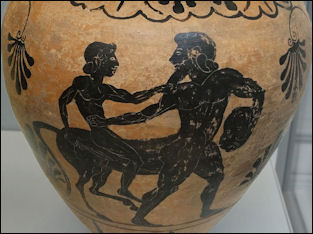

Etruscans and Greeks

The first Greek author to mention the Etruscans, whom the Ancient Greeks called Tyrrhenians, was the 8th-century BC poet Hesiod, in his work, the Theogony. He mentioned them as residing in central Italy alongside the Latins. The 7th-century BC Homeric Hymn to Dionysus referred to them as pirates. Unlike later Greek authors, these authors did not suggest that Etruscans had migrated to Italy from the east, and did not associate them with the Pelasgians. It was only in the 5th century BC, when the Etruscan civilization had been established for several centuries, that Greek writers started associating the name "Tyrrhenians" with the "Pelasgians", and even then, some did so in a way that suggests they were meant only as generic. [Source Wikipedia]

The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the western Mediterranean Sea. Here, their interests conflicted with those of the Greeks, especially in the sixth century BC, when Phocaeans of Italy founded colonies along the coast of Sardinia, Spain and Corsica. This led the Etruscans to ally themselves with Carthage, whose interests also conflicted with the Greeks.

Around 540 BC, the Battle of Alalia led to a new distribution of power in the western Mediterranean. Though the battle had no clear winner, Carthage managed to expand its sphere of influence at the expense of the Greeks, and Etruria saw itself relegated to the northern Tyrrhenian Sea with full ownership of Corsica. From the first half of the 5th century BC, the new political situation meant the beginning of the Etruscan decline after losing their southern provinces. In 480 BC, Etruria's ally Carthage was defeated by a coalition of Greek Magna Graecia cities led by Syracuse, Sicily. A few years later, in 474 B.C., Syracuse's tyrant Hiero defeated the Etruscans at the Battle of Cumae. Etruria's influence over the cities of Latium and Campania weakened, and the area was taken over by Romans and Samnites.

Etruscans and Romans

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The Etruscans dominated Italian civilization for roughly 500 years before the ascent of the Roman Republic. There’s a healthy academic debate about whether the Etruscans should be seen as the founders of Rome. The Romans and Etruscans were engaged in a series of wars that lasted hundreds of years. The conquest of Etruria is generally agreed to have been completed by 264 B.C., with the last Etruscan cities formally being absorbed into Rome by 27 B.C.. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 13, 2022]

Etruscan kings ruled Rome from 616 to 509 B.C. The first Etruscan king was Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. Rome’s last Etruscan king ascended to the throne in 535 B.C. The Romans threw him out in 509 and replaced the traditional monarchy with a republican government, blaming the king’s tyrannical behavior and holding it up as an example of the injustice of authoritarian rule.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The Etruscans were at their height between 600 and 480 B.C. Bronze production reached record levels and trade was conducted throughout the Mediterranean. The Etruscans founded colonies in the Po River Plain between 500 and 400 B.C.. During the fifth and forth centuries B.C., the Etruscans fought with the Romans, with one Etruscan city after another falling to Rome. In 474 B.C. The Etruscan fleet was defeated by Greeks in the battle of Cumae in the Bay of Naples. In 396 B.C., Veii, one of the most important Etruscan city, was sacked after a 12 year siege by the Romans. After the Second Punic War in 202 B.C. the once proud Etruscans were relegated to supplying grain and elements and spears for the Romans. By 90 B.C. they had been absorbed by Rome. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Etruscan Areas in Italy

Powerful Etruscan cities included Tarquinia, Vulci, Cerveteri, Vertolunia and Veii. Tarquinia was an important Etruscan city that flourished between 600 and 400 B.C. Located about 80 kilometers northwest of Rome, it is the home of a five-kilometer-long necropolis filled with more than 6,000 tombs cut into tufa hills between the 7th and 2nd centuries B.C. The tombs have have yielded much of what we know about the Etruscans.

Powerful Etruscan cities included Tarquinia, Vulci, Cerveteri, Vertolunia and Veii. Tarquinia was an important Etruscan city that flourished between 600 and 400 B.C. Located about 80 kilometers northwest of Rome, it is the home of a five-kilometer-long necropolis filled with more than 6,000 tombs cut into tufa hills between the 7th and 2nd centuries B.C. The tombs have have yielded much of what we know about the Etruscans.

The archeologist Alessando Mandolesi of the University of Turin told Archaeology magazine: Tarquinia “was one of the most powerful cities of the Etruscan league and a wealthy center of trade and commerce. You have to imagine people arriving from the port and seeing the two imposing mounds ...of the Tarquinian rulers.” According to Roman tradition Etruscan reached its height when one of its king married a Tarquinian noblewoman and brought a team of painters and artists from Tarquinia to Rome.

Fiesole, Chiusi, Volterra and Populonia were important Etruscan settlements in Tuscany. Fiesole (near Florence) is beautifully situated on a hill overlook the Arno. Here you can find a ruined Etruscan temple, a Roman amphitheater and bath and archeological museum with Roman and Etruscan treasures. Volterra (61 kilometers from Pisa) is situated among hills and crags and boasts an old Etruscan wall and museum.

Umbria also has a number of important Etruscan sites. Underneath Rocca Paolina fortress in Perguria is an underground city and near villa dela Prome is the largest Etruscan arch in Italy. The archeological museum in Tarquina has a fine Etruscan exhibit, including a beautiful pair of winged horses. There are also some excellent tomb painting in the Tarquina area but visitors generally aren't allowed in the tombs. A few miles away is Ipogeo di Volumni there is an interesting Etruscan tomb. There are also Etruscan sights in Todi, Bettona and Orvieto.

In 2018, Archaeology magazine reported: Italian authorities announced that they have identified the first Etruscan settlement ever found in Sardinia. The 9th-century B.C. site was strategically situated on the small island of Tavolara off the coast of Olbia. The settlement likely served as an important cultural and trade link between the Early Iron Age Sardinian Nuraghic communities and Etruscan cities on the Italian mainland, just across the Tyrrhenian Sea. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

A fourth-century B.C. Etruscan burial was found in Aleria, on the eastern side of the French island of Corsica archaeologists from France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) while excavating hundreds of graves dating from the third century B.C. through the third century A.D. in a Roman necropolis. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2019]

Origin of the Etruscans

The long-running controversy about the origins of the Etruscan people appears to be very close to being settled once and for all. Professor Alberto Piazza, from the University of Turin, Italy , a geneticist, told a conference of the European Society of Human Genetics that there is overwhelming evidence that the Etruscans were settlers from old Anatolia (now in southern Turkey). [Source: meta-religion.com, June 18, 2007]

The long-running controversy about the origins of the Etruscan people appears to be very close to being settled once and for all. Professor Alberto Piazza, from the University of Turin, Italy , a geneticist, told a conference of the European Society of Human Genetics that there is overwhelming evidence that the Etruscans were settlers from old Anatolia (now in southern Turkey). [Source: meta-religion.com, June 18, 2007]

The origins of the Etruscans have long been debated by archaeologists, historians and linguists. Three main theories have emerged: that the Etruscans came from Anatolia, Southern Turkey, as propounded by the Greek historian Herotodus; that they were indigenous to the region and developed from the Iron Age Villanovan society, as suggested by another Greek historian, Dionysius of Halicarnassus; or that they originated from Northern Europe.

Piazza and his colleagues study genetic samples from three present-day Italian populations living in Murlo, Volterra, and Casentino in Tuscany, central Italy. "We already knew that people living in this area were genetically different from those in the surrounding regions", he says. "Murlo and Volterra are among the most archaeologically important Etruscan sites in a region of Tuscany also known for having Etruscan-derived place names and local dialects. The Casentino valley sample was taken from an area bordering the area where Etruscan influence has been preserved."

The scientists compared DNA samples taken from healthy males living in Tuscany, Northern Italy, the Southern Balkans, the island of Lemnos in Greece, and the Italian islands of Sicily and Sardinia. The Tuscan samples were taken from individuals who had lived in the area for at least three generations. The samples were compared with data from modern Turkish, South Italian, European and Middle-Eastern populations. "We found that the DNA samples from individuals from Murlo and Volterra were more closely related those from near Eastern people than those of the other Italian samples", says Professor Piazza. "In Murlo particularly, one genetic variant is shared only by people from Turkey, and, of the samples we obtained, the Tuscan ones also show the closest affinity with those from Lemnos."

Scientists had previously shown this same relationship for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in order to analyse female lineages. And in a further study, analysis of mtDNA of ancient breeds of cattle still living in the former Etruria found that they too were related to breeds currently living in the near East.

Herodotus' theory, much criticised by subsequent historians, states that the Etruscans emigrated from the ancient region of Lydia, on what is now the southern coast of Turkey, because of a long-running famine. Half the population was sent by the king to look for a better life elsewhere, says his account, and sailed from Smyrna (now Izmir) until they reached Umbria in Italy. "We think that our research provides convincing proof that Herodotus was right", says Professor Piazza, "and that the Etruscans did indeed arrive from ancient Lydia.

Herodotus on the Etruscans and the Lydians

Herodotus theorized the Etruscans originated from Asia Minor, where he said there was great famine in 1200 B.C. According to his account, a great king divided his people in two and asked a leader from each to draw lots. The group that stayed evolved into the Lydians, who remained in western Asia Minor, and the other group left for Italy and became the Etruscans. Archaeologists surmise that there may be some truth to Herodotus's story because of the similarity between Etruscans and Lydian tombs.

Herodotus theorized the Etruscans originated from Asia Minor, where he said there was great famine in 1200 B.C. According to his account, a great king divided his people in two and asked a leader from each to draw lots. The group that stayed evolved into the Lydians, who remained in western Asia Minor, and the other group left for Italy and became the Etruscans. Archaeologists surmise that there may be some truth to Herodotus's story because of the similarity between Etruscans and Lydian tombs.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “According to Herodotus (1.94), the Etruscans were immigrants from Lydia in Asia Minor. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, however, was convinced that they were natives of Italy (1. 26-30), whereas Hellanicus of Lesbos, the earliest of the Atthidographers or chroniclers of Athens and a contemporary of Herodotus, claimed them as originally "Pelasgians", a rubric applied by Greek authors to an ethnically distinct group of ancestors, but one which is impossible to identify plausibly with any known civilization or settlement (cf. Hdt. 1. 57-8 on Pelasgians; DH 1.28 for Hellanikos on Etruscans).

“Most modern scholars believe that Herodotus is right about the Etruscans, or rather that the Etruscans as we know them represent a combination of local (i.e. Villanovan) and Asian elements, with a strong infusion of Greek culture for good measure. The difference between the Etruscans and what we find in the rest of Italy at this time is too great for the Etruscans to be purely a native phenomenon. The linguistic evidence also favors the immigration hypothesis. A 6th century B.C. inscription from Lemnos provides the closest known linguistic parallel to Etruscan. Lemnos is not Lydia but it is in the eastern Mediterranean, and some Lydians could have settled there. The alternative to supposing that this inscription is a trace of the same people who formed the backbone of Etruscan civilization is to suppose that these are independent survivals of a pre-Indo-European tongue; that seems far-fetched. But the tendency now is the regard the question as moot; it is more enlightening to trace the progress and the different stages of Etruscan culture than to inquire into their origins. ^*^

DNA Evidence of the Origins of Etruscans and Romans

A 2019 genetic study published in the journal Science analyzed the autosomal DNA of 11 Iron Age samples from the areas around Rome, concluding that Etruscans (900-600 BC) and the Latins (900-200 BC) from Latium vetus were genetically similar, and Etruscans also had Steppe-related ancestry despite speaking a pre-Indo-European language. [Source Wikipedia]

A 2021 genetic study published in the journal Science Advances analyzed the autosomal DNA of 48 Iron Age individuals from Tuscany and Lazio and confirmed that the Etruscan individuals displayed the ancestral component Steppe in the same percentages as found in the previously analyzed Iron Age Latins, and that the Etruscans' DNA completely lacks a signal of recent admixture with Anatolia or the Eastern Mediterranean, concluding that the Etruscans were autochthonous and they had a genetic profile similar to their Latin neighbors. Both Etruscans and Latins joined firmly the European cluster, 75 percent of the Etruscan male individuals were found to belong to haplogroup R1b, especially R1b-P312 and its derivative R1b-L2 whose direct ancestor is R1b-U152, while the most common mitochondrial DNA haplogroup among the Etruscans was H.

Lydia was located in present-day western Turkey

Andrew Curry wrote in Science: A new study of Etruscan DNA, however, shows these people were genetically the same as their neighbors—and argues that their culture and language were holdovers from an even earlier era. “They were a powerful formative influence on Rome in its early days,” says Harvard University historian Michael McCormick, a co-author on the new study: The first kings of Rome were Etruscan speakers, Etruscans may have founded the city of Rome itself, and many Roman institutions and cultural practices were borrowed or adapted from their Etruscan neighbors. [Source Andrew Curry, Science, September 24, 2021]

More recently the puzzle of their origins has deepened. Although linguists focused on the Etruscans’ seemingly exotic language, archaeologists saw signs of local ties. Etruscan art and artifacts seem to be part of a longer regional tradition, not a brand-new arrival in the area, says University of Cambridge archaeologist Graeme Barker, who was not involved in the research. “It’s hard to explain that away.”

The new study, of DNA from dozens of Etruscan-era skeletons taken from earlier excavations and museum collections, offers an explanation. In a paper published today in Science Advances, a team of archaeologists, geneticists, and linguists led by University of Tübingen geneticist Cosimo Posth finds the Etruscans were descended in part from Stone Age farmers who lived in Europe beginning around 6000 B.C.E. That would make them much like people elsewhere on the Italian Peninsula at the time, including their Latin neighbors. And like their neighbors, by 1600 B.C.E. the Etruscans seem to have absorbed an influx of new arrivals tracing their ancestry back to the open grasslands, or steppes, of modern-day Russia and Ukraine. “The Etruscans look indistinguishable from Latins, and they also carry a high proportion of steppe ancestry,” Posth says. That suggests the Etruscans were as local as anyone else in prehistoric Italy.

But that left the language question: In Italy, as with almost everywhere else in Europe, the arrival of steppe ancestry coincided with the arrival of Indo-European languages. “Usually, when Indo-European arrives, it supplants the languages that were there before,” says Leiden University linguist Guus Kroonen, a co-author of the paper. “So why do the Etruscans speak a non–Indo-European language?” The paper’s authors argue that Etruscan culture and language predate the arrival of the steppe people and was just particularly resilient: As new arrivals trickled into today’s Tuscany, they may have learned Etruscan, married into local families, and integrated into Etruscan society. “Almost everywhere else, these new people and new languages triumphed, along with their culture,” McCormick says. “Here, that didn’t happen: The old culture maintained itself and thrived.” Etruscan was spoken and used in tomb inscriptions for another 800 years, until the dominance of Rome and its Latin tongue pushed it quietly into extinction in the first century C.E.

To make sure the human remains they were sequencing were Etruscan, the scientists radiocarbon dated them, producing a bonus of sorts: Almost half of the skeletons archaeologists found in Etruscan-style tombs turned out to be from later periods. “People reused the Etruscan necropolises multiple times to bury their dead,” Posth says. The genetic makeup of these later remains showed outsiders continued to migrate to the region. At the height of the Roman Empire around 1 C.E., the DNA records a major contribution from the Eastern Mediterranean, perhaps from slaves brought to work on the farms of central Italy. And between 500 and 1000 C.E., an influx of DNA from Northern Europe testifies to the Germanic tribes that invaded and conquered the peninsula.

Etruscans Become More Urbanized and Cosmopolitan

Etruscan golden tablet with both Etruscan and Phoenician writing

On the relationship between the Lydians in Asia Minor (Turkey) and the Etruscans, Herodotus wrote in “The Histories” I.94 (c. 430 B.C.): “The Lydians have very nearly the same customs as the Hellenes, with the exception that these last do not bring up their girls the same way. So far as we have any knowledge, the Lydians were the first to introduce the use of gold and silver coin, and the first who sold good retail. They claim also the invention of all the games which are common to them with the Hellenes. These they declare that they invented about the time when they colonized Tyrrhenia [i.e., Etruria], an event of which they give the following account. In the days of Atys the son of Manes, there was great scarcity through the whole land of Lydia. [Source: Herodotus “The History of Herodotus” Book VI on the Persian War, 440 B.C. translated by George Rawlinson, MIT]

“For some time the Lydians bore the affliction patiently, but finding that it did not pass away, they set to work to devise remedies for the evil. Various expedients were discovered by various persons: dice, knuckle-bones, and ball, and all such games were invented, except checkers, the invention of which they do not claim as theirs. The plan adopted against the famine was to engage in games one day so entirely as not to feel any craving for food, and the next day to eat and abstain from games. In this way they passed eighteen years.

“Still the affliction continued, and even became worse. So the king determined to divide the nation in half, and to make the two portions draw lots, the one to stay, the other to leave the land. He would continue to reign over those whose lot it should be to remain behind; the emigrants should have his son Tyrrhenus for their leader. The lot was cast, and they who had to emigrate went down to Smyrna, and built themselves ships, in which, after they had put on board all needful stores, they sailed away in search of new homes and better sustenance. After sailing past many countries, they came to Umbria, where they built cities for themselves, and fixed their residence. Their former name of Lydians they laid aside, and called themselves after the name of the kings son, who led the colony, Tyrrhenians.”

DNA Evidence on the Origin of the Etruscans and Romans

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “To a lesser extent in the late 8th and 7th centuries the Etruscans were influenced by the Phoenicians, whose presence in the region centered around their colony at Carthage in North Africa, and settlements in western Sicily and on Sardinia. These gold bracelets from Praeneste, dated to around 675 B.C., show Phoenician themes. ^*^

“Now too, in the late 8th century, we begin to see greater social stratification in the grave goods. One example is the type of the warrior grave, represented by the helmet-topped urn. There are other indications, too, of the effectiveness of the Etruscans in warfare. The absence of any Greek or Phoenician colonies in Etruria ought to mean that the Etruscans were strong enough to prevent them from being founded. Oddly, there is no evidence for circuit walls around Etruscan cities earlier than the 6th century B.C. (at Roselle; the walls of Veii date to the 5th century). This could mean that Etruscan naval power was sufficient to keep the cities safe. Certainly ancient authors preserved a memory of Etruscan naval power (see Ephoros apud Strabo, 6.2.2; Homeric Hymn to Dionysus, 6-8; DH 1. 25; Pliny, NH 7.56.209).

“Finally, in this period the first signs of synoikism, the consolidation of villages into urban centers, appear in Etruria. The huts are being replaced (later 7th) by rectangular houses, with stone foundations and walls of unfired brick. Urbanization is a major component of the Etruscan legacy to Rome. In the Etruscan colony at Capua can be seen one of the the first true examples of the grid system, with the cardo (running N-S) and decumanus (E-W). Here we will leave the events of Etruscan history in the late 7th and 6th centuries for next time, as they become ever more closely entwined with Roman history as it crosses the line from fiction to fact.

Etruscan Government, Infrastructure and Economics

The Etruscans were governed under a lose confederation of city states, each controlled by oligarchies of the rich As was true in Greece, the Etruscans city states warred among themselves but were unable to unify against threats from the Romans and other peoples.

The Etruscans were governed under a lose confederation of city states, each controlled by oligarchies of the rich As was true in Greece, the Etruscans city states warred among themselves but were unable to unify against threats from the Romans and other peoples.

The Etruscans according to the Romans were masterful engineers and planners. Their cities were arranged in grid like blocks. Archaeological excavations have revealed fortifications, public buildings and temples. There is also evidence of urban planning. Some cities were laid out with separate zones for industry, residences and public housing.

The Etruscans built advanced roads with ruts of paved stones of wagon wheels, and grids of streets and sophisticated underwater passages. They used a surveying device called a “ groma” to build roads. In the 6th century Etruscan kings built some of the first streets, temples and water systems in Rome.

The Etruscans built sewers and drained the land that now makes up central Rome. They drained the swamp that later was the site of the Roman Forum and laid the foundation for the city's sewer system. They may have taught the Romans how to make aqueducts and sewers.

The Etruscans were mostly farmers. Archaeological excavations have revealed artisan’s workshops and kilns. They were also master sailors and traders. They traded throughout the Mediterranean, with Carthage in North Africa and Greece and its colonies. The Etruscans prized amber and traded with the Baltic region to get it. They also traded with but were suspicious of the Greeks who resided in colonies in southern Italy. Etruscan metals were traded throughout the Mediterranean. Some Greeks became quite wealthy trading Etruscan metals and Black Sea grains.

The Etruscans mined iron, copper and tin ore and traded these metals for perfume, ivory, amber and fine ceramics from Egypt, Greece and Phoenicia. Slaves were used as miners. The metal was worked in factories near the mine. Slag heaps from one their mine in Elba were mined by the Italians in World War I and II. Metal was traded with the Greeks for ceramics used in Etruscan tombs.

Roman Rebellion Against the Etruscans

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “In 509 B.C., so the story goes, the son of the Etruscan tyrant of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, fell in lust with a beautiful Roman bride called Lucretia. The young Superbus had no compunction in raping Lucretia and then casting her aside. In revenge, Lucretia’s family murdered the young Superbus and led the Romans in a rebellion against his father’s domination. They ousted the Etruscans and set up the Roman republic. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The defining moment of this rebellion came when a hero called Horatius single-handedly held the bridge across the River Tiber against an Etruscan army as his fellows cut it down behind him. It doesn't matter that the mythology is at best exaggerated and at worst untrue. The rebel republic was saved and went on to defeat its old masters, conquering great tracts of Italy in defence of its new-found liberty.” |::|

End and Legacy of Etruscans

By the 4th century B.C., Etruscan tomb art became dark. Pleasant scenes of parties and games became replaced with ones of violent battles and vicious creatures. There has been a great deal of debate among scholars as to whether this reflected a change in beliefs about the afterlife or a change in political or economic condition in Etruria or something else.

The Etruscan Civilization ended when it was overrun by Rome. The Romans besieged the Etruscan city states for 130 years before finally overcoming the last one, Velzna, in 265 B.C. Some scholars blame the Etruscan demise on their inability to change and adapt to challenges such as population growth, economic hardships and threats from their neighbors. Others blame the Etruscan demise on their failure on the Etrsucan towns and cities to unite into a single powerful state and their rigid class system.

Many Etruscan mining towns were suddenly abandoned at the end of the 6th century B.C. Most scholars think this was the result of an economic crisis such as a sudden decline in the profitability of mining but some think that industrial pollution and arsenic poisoning may have been the cause.

The Etruscans were instrumental in introducing Greek culture and the Greek alphabet to Rome. Their love of luxury also appears to have been passed on to the Romans.

The Tyrrhenian Sea on the west coast of Italy is named after the name the Greeks gave the Etruscans. The Adriatic is named after the Greco-Etruscan city of Adria. Tuscany is a Latin corruption of Etrusci, the name the Romans gave to the Etruscans.

The largest Etruscan settlement every found, a 7th century town covering at least 75 acres, was founded on the Tuscan plain near Lake Accessa. Archaeologists were so excited about the wealth of information obtained from the site the have called it the Etruscan Pompeii.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024