Home | Category: Philosophy

PLATO

Plato (427?-347 B.C.) was one of the world's most influential philosophers. A student of Socrates and a teacher of Aristotle, he is regarded as an idealist who explored justice and virtue in postwar Athens and founded the Academy. He and his philosophy gave birth to the concept of Platonic love, and the legend of Atlantis. Alfred North Whitehead said: “The safest general characterization of the whole Western philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”

Plato (427?-347 B.C.) was one of the world's most influential philosophers. A student of Socrates and a teacher of Aristotle, he is regarded as an idealist who explored justice and virtue in postwar Athens and founded the Academy. He and his philosophy gave birth to the concept of Platonic love, and the legend of Atlantis. Alfred North Whitehead said: “The safest general characterization of the whole Western philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”

The poet Antiphanes once said that Plato's words froze in the winter and thawed in the summer: the meaning being that his followers and students often didn't appreciate what he said until they were old and wise. Based on the number of books written about him (2,894 in 1999 in the Library of Congress collection), Plato is the world's tenth most famous person. He ranks behind Jesus and Lenin but ahead of Aristotle and Buddha. According to Amazon rankings and other sources he is the best-selling philosopher of all time.

Plato had many views on many things. For example, he wrote, witchcraft "persuades victims that...they are being harmed by those who are able to work magic." Plato also wrote about humorous, trivial things. He wrote about Alcibiades drunkeness and described Aristophanes "hiccoughing because he had eaten too much."

The Greek philosophers often equated beauty and mathematics. "Measure and commensurability," wrote Plato in “ Philebus”, "are everywhere identifiable with beauty and excellence." Describing the creation of the two sphere universe, Plato wrote: "Wherefore he made the world in the form of a globe, round as from a lathe, having its extremes in every direction equidistant from the center, the most perfect and the most like itself of all figures; for he considered that the like is infinitely fairer than the unlike."

RELATED ARTICLES:

SOCRATES' LIFE, CHARACTER, STUDENTS AND PLATO europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PLATO’S PHILOSOPHY AND VIEWS ON ETHICS, SCIENCE AND LOVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PLATO'S MAIN WORKS — THE REPUBLIC, CAVE AND IMMORTAL SOUL — AND THE MAIN IDEAS IN THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK PHILOSOPHY: HISTORY, PHILOSOPHERS, MAJOR SCHOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Plato’s Account of Socrates See SOCRATES'S PHILOSOPHIES, IDEAS, DISCUSSIONS AND THE SOCRATIC METHOD europe.factsanddetails.com

Plato’s Account of Socrates at the Symposia See SOCRATES AT A SYMPOSIA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Plato’s Account of Socrates’ Death See SOCRATES' TRIAL, DEFENSE AND DEATH Europe. factsanddetails.com

ATLANTIS: PLATO, LEGENDS AND THE SEACH FOR IT europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Plato: The Man and His Work” by A. E. Taylor (2011) Amazon.com;

“Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy” by Robin Waterfield (2023) Amazon.com;

“Plato's Academy Annotated Edition” by Paul Kalligas Amazon.com;

“Plato: Complete Works” by Plato , John M. Cooper, et al. (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Trial and Death of Socrates” by Plato , John M. Cooper , et al. (2000) Amazon.com;

“Symposium (Oxford World's Classics) by Plato Amazon.com;

“Republic” by Plato translated by Allan Bloom (2011) Amazon.com;

“Plato: Five Dialogues: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo (Hackett Classics)

by Plato, translated by John M. Cooper, et al. (2002) Amazon.com;

“Timaeus and Critias” (Penguin Classics), includes account of the rise and fall of Atlantis, by Plato, Thomas Kjeller Johansen, et al. (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Sophists” (Reprint Edition) by W. K. C. Guthrie (1906-1981) Amazon.com;

“Conversations of Socrates” (Penguin Classics) by Xenophon , Robin H. Waterfield , et al. Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Philosophers” by Editors of Canterbury Classics (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Philosophy: Thales to Aristotle (Readings in the History of Philosophy) by Reginald E. Allen (1991) Amazon.com;

“Greek Thought: A Guide to Classical Knowledge” by Jacques Brunschwig and Geoffrey E.R. Lloyd (Harvard University Press) Amazon.com;

“The Seekers” by Daniel Boorstin (1998) Amazon.com;

Plato’s Early Life

Plato (from Platon, "the broad shouldered") was born about 429 B.C. in Athens close to the time when Pericles died. He died in 347 B.C. just after the birth of Alexander the Great. Plato's real name was Aristocles.

Plato was born into a very rich and powerful noble family although some writers say he lived through periods of poverty. His father was related to the early leaders of Athens and his mother was a descendant of the democracy pioneer Solon and further back, it was said, Poseidon, god of the sea. Plato was intelligent, handsome and athletic and was raised in luxury. He received an typical upper class education in poetry, music, oratory and gymnastics. Many of his relatives were involved with Athenian politics, though Plato himself was not. Plato fought for several years as a soldier.

Plato grew up when Athens was in the middle of fighting the Peloponnesian War. Athens was defeated by Sparta in the war and was on the last legs of its Golden Age. Plato thought about pursuing a career in politics until he saw the horrors caused by war. Two of his relatives were killed trying to fight the ruling oligarchy in Athens, and his mentor, Socrates, was condemned to death on trumped political charges..

Plato and Socrates

Most of what know about Socrates is based on what Plato wrote about him. Plato was Socrates’ number one student. He learned a lot from Socrates about how to think, and what sort of questions to think about. He once said, Socrates was an “an absolute unlikeness to any human being that is or ever was."

Socrates and PlatoPlato was about the age of 19 when he became a student of Socrates. Plato was soldier at the time and went to listen to Socrates speak a war had ended. Plato remained faithful to Socrates until his death in 399 B.C. According to Plato's own account he began his professional life as a dramatist, and wrote a few tragedies, but gave all that up and even burned his manuscripts when he met Socrates

The master- pupil relationship between Socrates and Plato lasted about ten years and was a decisive influence in Plato's philosophical career. Before meeting Socrates he had, very likely, developed an interest in the earlier philosophers, and in schemes for the betterment of political conditions at Athens. At an early age he devoted himself to poetry. All these interests, however, were absorbed in the pursuit of wisdom to which, under the guidance of Socrates, he ardently devoted himself. [Source: Catholic Encyclopedia Article, 1913 |=|]

Plato was about 30 years old when Socrates died in 399 B.C.. He was very upset and began to write down some of the conversations he had heard Socrates have. Practically everything we know about Socrates comes from what Plato wrote down After a while, Plato began to write down his own ideas about philosophy instead of just writing down Socrates‘ ideas.

See Separate Articles"

SOCRATES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PLATO’S ACCOUNTS OF SOCRATES, HIS TRIAL AND DEATH AND THE SOCRATIC METHOD europe.factsanddetails.com

Plato After Socrates

After Socrates's death Plato fled Athens and may have traveled as far away as Egypt, where he studied history and mathematics. His writings on Egyptian customs and games seem to indicate that he really went to Egypt. He returned to Athens and embarked on a 12 year journey around the Mediterranean. In Sicily he angered a local tyrant. He was kidnaped into slavery and was released only after his friends paid a random.

A recently deciphered text from the Herculaneum papyrus scrolls firms up the circumstances surrounding Plato’s stint as a slave in either 399 B.C. after the death of Socrates or in 404 B.C. on the island of Aegina after the island was conquered by the Spartans. It was previously thought he had been sold into slavery in 387 B.C. while in Sicily. [Source: Barbie Latza Nadeau, CNN, May 1, 2024]

Also after the death of Socrates he joined a group of the Socratic disciples gathered at Megara under the leadership of Euclid. Later he travelled in Egypt, Magna Graecia, and Sicily. His profit from these journeys has been exaggerated by some biographers. There can, however, be no doubt that in Italy he studied the doctrines of the Pythagoreans. His three journeys to Sicily were, apparently, to influence the older and younger Dionysius in favor of his ideal system of government. But in this he failed, incurring the enmity of the two rulers, was cast into prison, and sold as a slave. Ransomed by a friend, he returned to his school of philosophy at Athens. [Source: Catholic Encyclopedia Article, 1913 |=|]

After returning to Athens he founded The Academy. After his return from his third journey to Sicily, he devoted himself unremittingly to writing and teaching until his eightieth year, when, as Cicero tells us, he died in the midst of his intellectual labors. |=|

Plato's Academy

In 387 B.C., after returning to Athens a second time, Plato founded the Academy, about a mile outside of Athens, in a garden near a gymnasium and grove sacred to the Hero Akedemus (also known as Hekademus), the source of the name Academy. At first Plato’s Academy was little more than a place where students gathered. Over time, Plato reputation as a lecturer grew and he received enough financial support from the aristocracy to have buildings constructed. A nobleman named Dionysuis II reportedly gave Plato the equivalent of half a million dollars.

Plato's Academy

The Academy has been called the first think tank and the first university but it had some unique features. There was no admission and no tuition fees. Plato got by on donations and presents from the rich parents of some of his students. The students reportedly dressed in elegant clothes in what were pleasant bucolic surroundings. They were encouraged to live ascetically and be celibate. Plato continued teaching at the Academy until his death at age 80.

Plato’s school differed from the Socratic School in many respects. It had a definite location in the groves near the gymnasium of Academus and its atmosphere was quite different than the marketplace where Socrates held court and gymnasiums where they the Sophists lectured. Students came from all over. They usually stayed for four years. Aristotle stayed for 20 years. The curriculum focused on mathematics and the pursuit of truth while its rival school in Athens, Isocrates, taught rhetoric and persuasion. The tone was more refined than the the Socratic School. More attention was given to literary form, and there was less indulgence in the odd, and even vulgar method of illustration which characterized the Socratic manner of exposition.

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “The Academy (Academia) was originally a public garden or grove in the suburbs of Athens, about six stadia from the city, named from Academus or Hecademus, who left it to the citizens for gymnastics (Paus. i. 29). It was surrounded with a wall by Hipparchus, adorned with statues, temples, and sepulchres of illustrious men; planted with olive and plane trees, and watered by the Cephisus. The olive-trees, according to Athenian fables, were reared from layers taken from the sacred olive in the Erechtheum, and afforded the oil given as a prize to victors at the Panathenean festival. The Academy suffered severely during the siege of Athens by Sylla, many trees being cut down to supply timber for machines of war.Few retreats could be more favorable to philosophy and the Muses. Within this enclosure Plato possessed, as part of his patrimony, a small garden, in which he opened a school for the reception of those inclined to attend his instructions. Hence arose the Academic sect, and hence the term Academy has descended to our times. The nameAcademia is frequently used in philosophical writings, especially in Cicero, as indicative of the Academic sect. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP)]

“Sextus Empiricus enumerates five divisions of the followers of Plato. He makes Plato founder of the first Academy, Aresilaus of the second, Carneades of the third, Philo and Charmides of the fourth, Antiochus of the fifth. Cicero recognizes only two Academies, the Old and the New, and makes the latter commence as above with Arcesilaus. In enumerating those of the old Academy, he begins, not with Plato, but Democritus, and gives them in the following order: Democritus, Anaxagoras, Empedocles, Parmenides, Xenophanes, Socrates, Plato, Speusippus, Xenocrates, Polemo, Crates, and Crantor. In the New, or Younger, he mentions Arcesilaus, Lacydes, Evander, Hegesinus, Carneades, Clitomachus, and Philo (Acad. Quaest. iv. 5). If we follow the distinction laid down by Diogenes, and alluded to above, the Old Academy will consist of those followers of Plato who taught the doctrine of their master without mixture or corruption; the Middle will embrace those who, by certain innovations in the manner of philosophizing, in some measure receded from the Platonic system without entirely deserting it; while the New will begin with those who relinquished the more questionable tenets of Arcesilaus, and restored, in come measure, the declining reputation of the Platonic school.

Plato's Academy

“Views of the New Academy. The New Academy begins with Carnades (i.e. the Third Academy for Diogenes) and was largely skeptical in its teachings. They denied the possibility of aiming at absolute truth or at any certain criterion of truth. Carneades argued that if there were any such criterion it must exist in reason or sensation or conception; but as reason depends on conception and this in turn on sensation, and as we have no means of deciding whether our sensations really correspond to the objects that produce them, the basis of all knowledge is always uncertain. Hence, all that we can attain to is a high degree of probability, which we must accept as the nearest possible approximation to the truth. The New Academy teaching represents the spirit of an age when religion was decaying, and philosophy itself, losing its earnest and serious spirit, was becoming merely a vehicle for rhetoric and dialectical ingenuity. Cicero's speculative philosophy was in the main in accord with the teachings of Carneades, looking rather to the probable (illud probabile) than to certain truth (see his Academica).

Plato's Academy provided a model for universities and social and scientific academies that developed later. His students, which included Demosthenes, Aristotle, Lycurgus and several women, studied mathematics, philosophy, law and music.

Academy in A.D. 160

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “Before the entrance to the Academy is an altar to Love, with an inscription that Charmus was the first Athenian to dedicate an altar to that god. The altar within the city called the altar of Anteros (Love Avenged) they say was dedicated by resident aliens, because the Athenian Meles, spurning the love of Timagoras, a resident alien, bade him ascend to the highest point of the rock and cast himself down. Now Timagoras took no account of his life, and was ready to gratify the youth in any of his requests, so he went and cast himself down. When Meles saw that Timagoras was dead, he suffered such pangs of remorse that he threw himself from the same rock and so died. From this time the resident aliens worshipped as Anteros the avenging spirit of Timagoras. In the Academy is an altar to Prometheus, and from it they run to the city carrying burning torches. The contest is while running to keep the torch still alight; if the torch of the first runner goes out, he has no longer any claim to victory, but the second runner has. If his torch also goes out, then the third man is the victor. If all the torches go out, no one is left to be winner. There is an altar to the Muses, and another to Hermes, and one within to Athena, and they have built one to Heracles. There is also an olive tree, accounted to be the second that appeared. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“Not far from the Academy is the monument of Plato, to whom heaven foretold that he would be the prince of philosophers. The manner of the foretelling was this. On the night before Plato was to become his pupil Socrates in a dream saw a swan fly into his bosom. Now the swan is a bird with a reputation for music, because, they say, a musician of the name of Swan became king of the Ligyes on the other side of the Eridanus beyond the Celtic territory, and after his death by the will of Apollo he was changed into the bird. I am ready to believe that a musician became king of the Ligyes, but I cannot believe that a bird grew out of a man. In this part of the country is seen the tower of Timon, the only man to see that there is no way to be happy except to shun other men. There is also pointed out a place called the Hill of Horses, the first point in Attica, they say, that Oedipus reached — this account too differs from that given by Homer, but it is nevertheless current tradition — and an altar to Poseidon, Horse God, and to Athena, Horse Goddess, and a chapel to the heroes Peirithous and Theseus, Oedipus and Adrastus. The grove and temple of Poseidon were burnt by Antigonus1 when he invaded Attica, who at other times also ravaged the land of the Athenians.

“Near the Hill of Ares is shown a ship built for the procession of the Panathenaea. This ship, I suppose, has been surpassed in size by others, but I know of no builder who has beaten the vessel at Delos, with its nine banks of oars below the deck. Outside the city, too, in the parishes and on the roads, the Athenians have sanctuaries of the gods, and graves of heroes and of men. The nearest is the Academy, once the property of a private individual, but in my time a gymnasium. As you go down to it you come to a precinct of Artemis, and wooden images of Ariste (Best) and Calliste (Fairest). In my opinion, which is supported by the poems of Pamphos, these are surnames of Artemis. There is another account of them, which I know but shall omit. Then there is a small temple, into which every year on fixed days they carry the image of Dionysus Eleuthereus. Such are their sanctuaries here, and of the graves the first is that of Thrasybulus son of Lycus, in all respects the greatest of all famous Athenians, whether they lived before him or after him. The greater number of his achievements I shall pass by, but the following facts will suffice to bear out my assertion. He put down what is known as the tyranny of the Thirty1, setting out from Thebes with a force amounting at first to sixty men; he also persuaded the Athenians, who were torn by factions, to be reconciled, and to abide by their compact. His is the first grave, and after it come those of Pericles, Chabrias and Phormio. There is also a monument for all the Athenians whose fate it has been to fall in battle, whether at sea or on land, except such of them as fought at Marathon. These, for their valor, have their graves on the field of battle, but the others lie along the road to the Academy, and on their graves stand slabs bearing the name and parish of each.”

“Near the Hill of Ares is shown a ship built for the procession of the Panathenaea. This ship, I suppose, has been surpassed in size by others, but I know of no builder who has beaten the vessel at Delos, with its nine banks of oars below the deck. Outside the city, too, in the parishes and on the roads, the Athenians have sanctuaries of the gods, and graves of heroes and of men. The nearest is the Academy, once the property of a private individual, but in my time a gymnasium. As you go down to it you come to a precinct of Artemis, and wooden images of Ariste (Best) and Calliste (Fairest). In my opinion, which is supported by the poems of Pamphos, these are surnames of Artemis. There is another account of them, which I know but shall omit. Then there is a small temple, into which every year on fixed days they carry the image of Dionysus Eleuthereus. Such are their sanctuaries here, and of the graves the first is that of Thrasybulus son of Lycus, in all respects the greatest of all famous Athenians, whether they lived before him or after him. The greater number of his achievements I shall pass by, but the following facts will suffice to bear out my assertion. He put down what is known as the tyranny of the Thirty1, setting out from Thebes with a force amounting at first to sixty men; he also persuaded the Athenians, who were torn by factions, to be reconciled, and to abide by their compact. His is the first grave, and after it come those of Pericles, Chabrias and Phormio. There is also a monument for all the Athenians whose fate it has been to fall in battle, whether at sea or on land, except such of them as fought at Marathon. These, for their valor, have their graves on the field of battle, but the others lie along the road to the Academy, and on their graves stand slabs bearing the name and parish of each.”

Plato Becomes More Dogmatic

In 367 B.C., Dionysus II, a friend of Plato’s family, became the leader of Syracuse, a powerful colony in Sicily, and invited Plato to come and help set up a government. Plato saw this as a chance to create a utopian republic like the one described in his book. It turns out Dionysus II was a foolish leader and Plato’s venture was a disaster. He had to flee for his life. One of his favorite students was murdered.

After Plato’s nasty experience with Dionysus II in Sicily, the conversation segments in his dialogues became increasing longer and more like monologues as Plato’s philosophy moved away from the Socrates call-and-response style to dogma. In one of his later works, “ Laws” , he demanded that men obey earthly laws rather than seek a utopia “laid up in heaven.” The historian Daniel Boorstin said that in doing this Plato “displaced the question by the answer.”

Scroll Charred by Vesuvius Eruption Reveals Plato’s Final Hours

Newly-deciphered text from the Herculaneum papyrus scrolls, which were charred after being buried under layers of volcanic ash following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D, appear to reveal the location of Plato burial and how he spent his last hours before he died in 347 B.C., Italian researchers said. He is believed to have been buried in a secret garden near the sacred shrine to Muses inside the Platonic Academy of Athens that had been reserved for him, according to Graziano Ranocchia, professor of Papyrology at the Department of Philology, Literature and Linguistic at the University of Pisa. It was previously only known that he was buried in the academy, but not specifically where, Ranocchia told CNN.

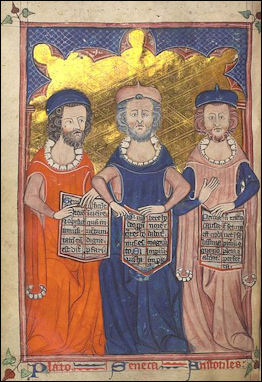

Plato, Seneca, Aristotle

The scroll documents the history of Greek philosophy. About a 1,000 words on it were deciphered. It says Plato spent his last evening listening to a musician, though he criticized her rhythmic abilities, according to The Guardian and the Independent. According to ancient sources, he died hours later in his sleep, or perhaps at a wedding feast. [Source: Brendan Rascius, Miami Herald, May 2, 2024]

Barbie Latza Nadeau of CNN wrote: The text also provides more detail about Plato’s final night — and he wasn’t a fan of the music that was played. It had previously been thought that the so-called “sweet notes” played by a slave woman from Thrace were pleasing to Plato, experts said. But the texts now reveal that in fact, despite running a high fever on his deathbed, he found that the flute music had a “scant sense of rhythm,” according to Ranocchia, who said he made the comments to a guest from Mesopotamia.“He was running a high fever and was bothered by the music they were playing,” Ranocchia said. [Source: Barbie Latza Nadeau, CNN, May 1, 2024]

The text is part of around 1,800 carbonized scrolls discovered in the 18th century in a building believed to have belonged to the father-in-law of Julius Caesar, who lived in Herculaneum, a seaside town about 20 kilometers (12 miles) from Pompeii. Experts are using AI along with optical coherence tomography, an imaging technique, and infrared hyperspectral imaging technology to read sequences of previously hidden text from the papyri that had been partially destroyed. The latest discovery came from a passage of more than 1,000 words — about 30 percent of the text — that had been deciphered and re-deciphered over the last year, according to Ranocchia, who presented the findings at the University of Naples on April 23, 2024.

Platonic School

“Plato's School, like Aristotle's, was organized by Plato himself and handed over at the time of his death to his nephew Speusippus, the first scholarch, or ruler of the school. It was then known as the Academy, because it met in the groves of Academus. The Academy continued, with varying fortunes, to maintain its identity as a Platonic school, first at Athens, and later at Alexandria until the first century of the Christian era. [Source: Catholic Encyclopedia Article, 1913 |=|]

“There were, however, episodes, so to speak, of Platonism in the history of Scholasticism — e.g., the School of Chartes in the twelfth century — and throughout the whole scholastic period some principles of Platonism, and especially of neo-Platonism, were incorporated in the Aristotelean system adopted by the schoolmen. The Renaissance brought a revival of Platonism, due to the influence of men like Bessarion, Plethon, Ficino, and the two Mirandolas Giovanni Pico and Giovanni Francesco Pico. The Cambridge Platonists of the seventeenth century, such as Cudworth, Henry More, Cumberland, and Glanville, reacting against humanistic naturalism, "spiritualized Puritanism" by restoring the foundations of conduct to principles intuitionally known and independent of self-interest. outside the schools of philosophy which are described as Platonic there are many philosophers and groups of philosophers in modern times who owe much to the inspiration of Plato, and to the enthusiasm for the higher pursuits of the mind which they derived from the study of his works. |=|

“It’s possible that Plato’s ideas about the difference between reality and the illusion we perceive are related to Hindu and Buddhist ideas about nirvana, which were forming in India about the same time. You could also compare the parable of the cave to the Indian story of the Blind Men and the Elephant, which was written around the same time. [Source: Karen Carr, History for Kids]

Platonic School and Christianity

Some scholars have argued that many of the basic doctrines of Christianity owe as much to Plato as they do to Jesus. Plato denounced the material world and the pleasures of the flesh, which is one reason why he was popular among Christian theologians. Plato wrote: "Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy...cities will never cease from ill, nor the human race."

Christianity modified the Platonic system in the direction of mysticism and demonology, and underwent at least one period of scepticism. It ended in a loosely constructed eclecticism. With the advent of neo-Platonism founded by Ammonius and developed by Plotinus, Platonism definitely entered the cause of Paganism against Christianity. [Source: Catholic Encyclopedia Article, 1913 |=|]

“The great majority of the Christian philosophers down to St. Augustine were Platonists. They appreciated the uplifting influence of Plato's psychology and metaphysics, and recognized in that influence a powerful ally of Christianity in the warfare against materialism and naturalism. These Christian Platonists underestimated Aristotle, whom they generally referred to as an "acute" logician whose philosophy favoured the heretical opponents of orthodox Christianity. The Middle Ages completely reversed this verdict. The first scholastics knew only the logical treatises of Aristotle, and, so far as they were psychologists or metaphysicians at all, they drew on the Platonism of St. Augustine. Their successors, however, in the twelfth century came to a knowledge of the psychology, metaphysics, and ethics of Aristotle, and adopted the Aristotelean view so completely that before the end of the thirteenth century the Stagyrite occupied in the Christian schools the position occupied in the fifth century by the founder of the Academy.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024