Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society / Science and Philosophy

MEASUREMENTS OF TIME IN ANCIENT ROME

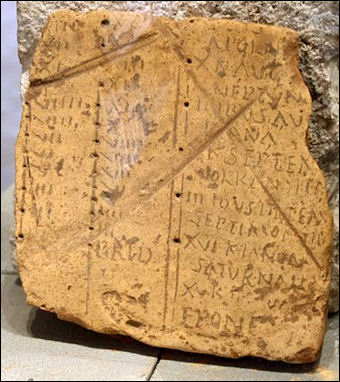

replica of a portable sundial, Roman Egypt AD 4th century

The year one on the Christian calendar was regarded as the year 745 A.U.C (“ab urbe condita” —“from the foundation of the city”) on the Roman calendar. It marked the year that Romulus and Remus founded Rome. Romans initially counted days and the equivalent of weeks and months with Kalends, Nones and Ides.

The Romans developed the idea of the week and gave names to the months. They had an eight-day week which they later changed to seven. By the A.D. third century Romans divided the day into only two parts: before midday “(ante meridiem” A.M.) and after midday (“ post meridiem” P.M.). Someone was in charge of noticing when the sun crossed the meridiem since lawyers were supposed to appear before noon. Later the day was dived into parts: early morning, forenoon, afternoon, and evening and eventually followed a sundial that marked "temporary" hours.

The ancient Greeks had no weeks, nor names for the different days. They followed a 12 month calendar similar to the one used by Babylonians with 29 and 30 day lunar months and a 13th month added on the seventh of thirteen years to ensure that the calendar stayed in sync with the seasons. Each city state added the thirteen month at different times to mark local festivals and suit political needs. A complex system of "intercalculating" was employed to decide on meeting times between citizens of different states and to make arrangements for the pick-up and delivery of goods. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

Long before they were applied to time, seconds and minutes were used to represent units on a circle or arc. In the Greco-Roman era, Ptolemy used the units, based on the Babylonian base-60 system, on his maps. In the Middle Ages, minutes used on circular clock dials. Seconds as a time measurement were introduced in the late 17th century when clocks accurate enough to tick off seconds were developed.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SCIENCE IN ANCIENT ROME: MEASURMENTS, NUMBERS, PLINY THE ELDER factsanddetails.com

TIME IN ANCIENT GREECE: CLOCKS, DIVISIONS, DAYS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN TECHNOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com;

ARCHIMEDES AND HIS INVENTIONS europe.factsanddetails.com;

ANCIENT ROMAN INFRASTRUCTURE: BRIDGES, TUNNELS, PORTS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN AQUEDUCTS: HISTORY, CONSTRUCTION AND HOW THEY WORKED europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Time in Antiquity” by Robert Hannah Amazon.com;

“Roman Portable Sundials: The Empire in your Hand” by Richard J.A. Talbert (2017) Amazon.com;

“Time and Cosmos in Greco-Roman Antiquity” by Alexander R. Jones , John Steele, et al. | (2016) Amazon.com;

“On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity” by Michele Renee Salzman (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Discoverers” by Daniel Boorstin (1985) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Calendars: Constructions of Time in the Classical World” by Robert Hannah (2005) Amazon.com;

“Sundials: Their Theory and Construction” by Albert Waugh (1973) Amazon.com;

“Down to the Hour: Short Time in the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East (Time, Astronomy, and Calendars: Texts and Studies” by Kassandra J. Miller (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Timepiece of Shadows: a History of the Sun Dial”

by Henry Spencer Spackman (1895) Amazon.com;

“The Time Museum, Volume I, Time Measuring Instruments; Part 3, Water-clocks, Sand-glasses, Fire-clocks” by Anthony J. Turner (1984) Amazon.com;

“Roman Origins of Our Calendar” by Van L. Johnson (1974) Amazon.com;

“Cæsar's Calendar: Ancient Time and the Beginnings of History” by Denis Feeney (2008) Amazon.com;

“Calendarium Perpetuum: A Modern Edition of the Ancient Roman Calendar”

by L. Vitellius Triarius (2013) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“The Calendar: The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Calendars and Constellations” by Emmeline M. Plunket (1903) Amazon.com;

“A Week in the Life of Rome” by James L. Papandrea (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic: An Introduction to the Calendar and Religious Events of the Roman Year” by W Warde Fowler (1899) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Holidays” by Mab Borden (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Festivals in the Greek East: From the Early Empire to the Middle Byzantine Era” by Fritz Graf (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Sundials in Ancient Rome

The place of our clock was taken by the sundial, such as is often seen nowadays in our parks and gardens; this measured the hours of the day by the shadow of a stick or pin. Although sundials had been around at least since 1500 B.C. in ancient Egypt they became more sophisticated and common place under the Romans. Roman sundials not only mapped out hours they cut them into halves and quarters. Not everyone was happy about the advancement. The Roman playwright Plautus wrote in the 2nd century B.C.: “The gods confound the man who first found out how to distinguish the hours. Confound him, who in this place set up a sundial, to cut and hack up my days so wretchedly into small pieces!”

The principle of the sun-dial was sometimes applied on a grandiose scale: in 10 B.C., for instance, Augustus erected in the Campus Martius the great obelisk of Montecitorio to serve as the giant gnomon whose shadow would mark the daylight hours on lines of bronze inlaid into the marble pavement below. Sometimes, on the other hand, it was applied to more and more minute devices which eventually evolved into miniature solaria or pocket dials that served the same purpose as our watches. Pocket sun-dials have been discovered at Forbach and Aquileia which scarcely exceed three centimeters in diameter. But at the same time the public buildings of the Urbs and even the private houses of the wealthy were tending to be equipped with more and more highly perfected water-clocks. From the time of Augustus, clepsydrarii and organarii rivalled each other in ingenuity of construction and elaboration of accessories. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Roman sundials were influenced by Greek sundials, See Sundails Under TIME IN ANCIENT GREECE: CLOCKS, DIVISIONS, DAYS europe.factsanddetails.com

Sundials As Status Symbols in Ancient Rome

Roman sundial

Some Roman sundails were made with great craftsmanship and regarded as status symbols. One Roman Limestone sundial — dated to the mid-1st century B.C., foundin Interamna Lirenas, Italy, and measures 54 centimeters (21.25 inches) wide 35 centimeters (13.8 inches high and 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) thick — belonged to a man named Marcus Novius Tubula, son of Marcus, who was elected to one of Rome’s most ancient offices, that of tribune of the plebs. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

According to Archaeology magazine: For Marcus, the event was significant enough to celebrate by commissioning a sundial to be displayed in a prominent spot in his hometown. He had his name inscribed on the base of the sundial, and paid for the whole thing “De Sua PECUNIA,” or with his own money. The plebeian tribune, established in 494 B.C., was the first office to be open to the common people and was intended to check patrician abuse of power. During most of the Republican period (509–27 B.C.), it was one of the most powerful offices in Rome — although by the time Marcus became tribune the position had lost much of its influence.

“Several hundred ancient Roman sundials have been found, but very few are in such good condition — and even fewer are inscribed — making the example from Interamna Lirenas a rare find. What is especially intriguing is that a tribune of the plebs could have come from this “average” town 50 miles from the capital. “The fact that someone managed to gain access to a relatively important public office in Rome says that some of the town’s inhabitants had the material resources and personal connections necessary to pursue such political ambitions,” says Alessandro Launaro of the University of Cambridge, who is directing the exploration there. “This casts new light on the level of involvement in Rome’s affairs to which individuals hailing from this and other relatively secondary communities could aspire.”

In Petronius' romance, which represents Trimalchio as "a highly fashionable person" (lautissimus homo), his confederates frankly.justified the admiration they felt for him: "Has he not got a clock in his dining-room? And a uniformed trumpeter to keep telling him how much of his life is lost and gone?" Trimalchio, moreover, has stipulated in his will that his heirs shall build him a sumptuous tomb, with a frontage of one hundred feet and a depth of two hundred, "and let there be a sun-dial in the middle, so that anyone who looks at the time will read my name whether he likes it or not." This quaint appeal to posterity would have no point if Trimalchio's contemporaries had not been accustomed frequently to consult their clocks. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Evolution of Sundials and Hours in Ancient Rome

Hours and the word for them were invented from the Greeks. Roman divided their days in 24 hours. Otherwise their hours were very different from ours and they evolved over time. Toward the end of the fifth century B.C. Romans had learned to observe the stages of the sun as its moved across the sky. The apparent path of the sun varied of course with the latitude of each place, and the length of the shadow cast by the. stylus was consequently different in one city and another. At Alexandria it was only three-fifths of the height of the stylus, at Athens three-quarters; it was nearly nine-elevenths at Tarentum and reached eight-ninths at Rome. As many different sun-dials had to be constructed as there were different cities. The Romans were among the last to appreciate the need. And just as they felt no need to count the hours till two centuries after the Athenians, so they took another hundred years to learn to do it accurately. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

sundial

At the end of the fourth century B.C. they were still content to divide the day into two parts, before midday and after. Naturally the important thing was then to note the moment when the sun crossed the meridian. One of the consul's subordinates was told off to keep a lookout for it and to announce it to the people busy in the Forum, as well as to the lawyers who, if their pleadings were to be valid, must present themselves before the tribunal before midday. The herald's instructions were to make his announcement when he saw the sun "between the rostra and the graecostasis" which clearly proves that his functions were of relatively recent date. For there could be no mention of the rostra until the speaker's tribune in the Forum had been adorned with the beaks (rostra) of the ships captured from the Antiates by Duilius in 338 B.C.; nor could there have been a graecostasis intended for the reception of Greek envoys until the first Greek embassy had been received in Rome, which would appear to have been that sent by Demetrius Poliorcetes to the Senate about 306 B.C.

By the late third century B.C. some slight progress had been made by dividing the two halves of the day into two parts: into the early morning and forenoon (mane and ante meridiem) on the one hand; and on the other, into afternoon and evening (de meridie and suprema). But it was not until the beginning of the First Punic War in 264 B.C. that the "hours" and the horologium of the Greeks were introduced into the city. One of the consuls of that year, M' Valerius Messalla, had brought back with other booty from Sicily the sun-dial of Catana and set it up as it was on the comitium, where for more than three generations the lines engraved on its icoXog for another latitude continued to supply the Romans with an artificial time. In spite of the assertionof Pliny the Elder that they blindly obeyed it for ninety-nine years, we must be permitted to believe that they persisted in ignorance rather than in wilful error. They probably took no interest at all in Messalla's sun-dial and continued to govern their day in the old happy-go-lucky manner by the apparent course of the sun above the monuments of their public places, as if the horologium had never existed.

In the year 164 B.C., however, the enlightened generosity of the censor Q. Marcius Philippus endowed the Romans with their first horologium accurately calculated for their own latitude and hence reasonably accurate, and if we are to believe Pliny the Naturalist they welcomed the gift as a coveted treasure. For thirty years their legions had fought in Greek territory, almost without ceasing, first against Philip V, then against the Aetolians and Antiochus of Syria, finally against Perseus; and they had gradually become familiar with the possessions of their enemies. At times, perhaps, they had toyed, without undue success, with a system of hours a trifle less erratic and uncertain than the one that had hitherto sufficed them. So they were pleased to have a sun-dial brought home and fitted up in their own country. Not to be behind Q. Marcius Philippus, the censors who succeeded him in office, P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica and M. Popilius Laenas, completed the work he had begun by flanking his sun-dial with a water-clock to supplement its services at night or on days of fog.

Waterclocks in Ancient Rome

Like their Athenian counterpart, the Roman waterclock was a bowl with a hole near the bottom that measured about 20 minutes. These devised were used in courts and government legal proceedings to limit the speaking time of lawyers, officials and orators. In Rome, the expression "to lose water" meant wasting time and "to grant water" meant to allocate a lawyer more time. Longwinded speakers in the Senate were chided that "their water should be taken away" By the time water clocks were perfected in Europe they were soon replaced by swinging pendulum and spring activated clocks.

waterclock from the Agora in Athens

In the second century B.C. the water-clock (clepsydra) was also borrowed from the Greeks. This was more useful because it marked the hours of the night as well as of the day and could be used in the house. It consisted essentially of a vessel filled at a regular time with water, which was allowed to escape from it at a fixed rate, the changing level marking the hours on a scale. As the length of the Roman hours varied with the season of the year and the flow of the water with the temperature, the apparatus was far from accurate. Shakespeare’s reference in Julius Caesar (II, i, 192) to the striking of the clock is an anachronism.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Nothing could well have been simpler than the mechanism of the water-clock. Let us imagine the clepsydra that is, a transparent vessel of water with a regular intake placed near a sun-dial. When the gnomon casts its shadow on a curve of the polos, we need only to mark the level of the water at that moment by incising a line on the outside of the watercontainer. When the shadow reaches the next curve of the polos, we make another mark, and so on until the twelve levels registered correspond to the twelve hours of the day chosen for our experiment.[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Once the sun-dial had lent its services for grading the waterclock, there was no further need to have recourse to the dial, and it was a simple matter to extend the readings to serve for the night hours. It is easy to imagine that the use of clepsydrae soon became general in Rome. However, the agreement between the sun-dial and the water-clock was still far from being exact. The gnomon of the sun-dial was correct only in the degree in which its maker had adapted it to the latitude of the place where it stood; and as.for the water-clock, whose measurements lumped all the days of one month together though the sun would have lighted each differently, its makers could never prevent certain inaccuracies in its floats creeping in to falsify the corrections they had been able to make in the readings of the gnomon.

As our clocks have their striking apparatus and our public clocks their peal of bells, the horologia ex aqua which Vitruvius describes were fitted with automatic floats which "struck the hour" by tossing pebbles or eggs into the air or by emitting warning whistles. The fashion in such things grew and spread during the second century of our era. In the time of Trajan a water-clock was as much a visible symbol of its owner's distinction and social status as a piano is for certain strata of our middle classes today.

Variable Hours and Concepts of Time in Ancient Rome

Time at Rome was never more than approximate. If anyone asked the time, he was certain to receive several different answers at once for, as Seneca asserts, it was impossible at Rome to be sure of the exact hour; and it was easier to get the philosophers to agree among themselves than the clocks: "horam non possum certam tibi dicer e: facilius inter philosophos guam inter horologia convenit" [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Time was perpetually fluid or, if the expression is preferred, contradictory. The hours were originally calculated for daytime; and even when the water-clock made it possible to calculate the night hours by a simple reversal of the data which the sun-dial had furnished, it did not succeed in unifying them. The horologia ex aqua was built to reset itself, that is, to empty itself afresh for night and day. Hence a first discrepancy between the civil day, whose twenty-four hours reckoned from midnight to midnight, and the twenty-four hours of the natural day which was officially divided into two groups of twelve hours each, twelve of the day and twelve of the night.

Roman calendar It is clear that the hourly division of the day had become part and parcel of their everyday routine. On the other hand, it would be an error to suppose that the Romans lived with their eyes glued to the needles of their sun-dials or the floats of their water-clocks as ours are to the hands of our watches. They were not yet like us the slaves of time, for they still lacked both perseverance and punctuality. This being granted, it is clear that if we give our clepsydra a cylindrical form we can engrave on it from January to December twelve vertical lines corresponding to the twelve months of the year. On each of these verticals we then mark the twelve hourly levels registered for the same day of each month; and finally, by joining with a curved line the hour signs which punctuate the monthly verticals, we can read off at once from the level of the water above the line of the current month the hour which the needle of the sun-dial would have registered at that moment if the sun had happened to be shining.

Nor was this all. While our hours each comprise a uniform sixty minutes of sixty seconds each, and each hour is definitely separated from the succeeding by the fugitive moment at which it strikes, the lack of division inside the Roman hour meant that each of them stretched over the whole interval of time between the preceding hour and the hour which followed; and this hour interval instead of being of fixed duration was perpetually elastic, now longer, now shorter, from one end of the year to the other, and on any given day the duration of the day hours was opposed to the length of the night hours. For the twelve hours of the day were necessarily divided by the gnomon between the rising and the setting of the sun, while the hours of the night were conversely divided between sunset and sunrise; in proportion as the day hours were longer at one season, the night hours were, of course, shorter, and vice versa. The day hours and night hours were equal only twice a year: at the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. They lengthened, and shortened in inverse ratio till the summer and winter solstices, when the discrepancy between them reached its maximum. At the winter solstice (December 22), when the day had only 8 hours, 54 minutes of sunlight against a night of 15 hours, 6 minutes, the day hour shrank to 44 percent minutes while in compensation the night hour lengthened to i hour, 15 percent minutes. At the summer solstice the position was exactly reversed; the night hour shrank to its minimum while the day hour reached its maximum.

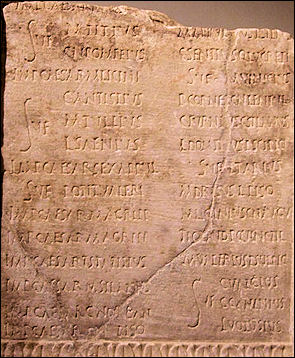

Roman Calendar

Originally the Roman year began on March 25 and had 10 months (six 30-day months and four 31-day months) and a 60-day winter stretch that appears to have been ignored. In the 7th century B.C. the second Roman king, Numa Pompilius, added two months, January and February, and they became the beginning of the year. The year was still only 355 days though. A century later a 13th month was added that yielded a year with 366¼ days.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: From the seventh century B.C. onwards, the Romans had tried to follow the lunar calendar. The pontifices, an official college of Roman priests, were responsible for overseeing the calendar and would regularly add days to the year in order extend political terms and try and rig the outcome of elections. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 31, 2017]

By Caesar's time spring and the vernal equinox began in mid May. In 153 B.C., the Senate declared that the year would begin on January 1st but the changes didn't take place until 46 B.C. when Julius Caesar aimed to set the record straight. After spending time with Cleopatra in Alexandria and becoming exposed to the Egyptian calendar, Caesar returned home to Rome in 47 B.C. and adapted the Egyptian calendar to the Roman one. Caesar added 90 days to 46 B.C. which lasted 445 days and became known as the "Year of Confusion."

Early calendars had no year 0 because the Romans hadn't devised zero. The year of Christ' birth was designated as 1 A.D. Orthodox Christians continued to observe Easter according to Julian calendar. Other Christians now mark Easter by the Gregorian Calendar.

Julian Calendar

The Julian calendar, established in 46. B.C. by Julius Caesar and worked out by the Alexandrian astronomer Sosgenes, had 12 months, 365 days and one leap day every four years between February 23 and February 24. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: January 1st became known as the New Year in 45 B.C. Julius Caesar reformed the Roman calendar in an effort to prevent abuses of the electoral system mentioned above. He sought the advice of the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, who recommended that the Romans shift to the solar calendar (which just so happened to be the Egyptian way). In order to bring this about, Caesar added sixty-seven days to 45 B.C. so that 46 B.C. began in January rather than March. Realizing that the length of the year was approximately 365.25 days he also instituted the practice of adding an additional day to February every fourth year. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 31, 2017]

The new Julian calendar was only 11 minutes and 14 seconds out of synch with the actual solar year (one revolution of the earth around the sun). Initially Romans read Caesar's edict for the new system wrong and leap day occurred every third year. Augustus rectified the error in 8 B.C. The 11 minutes and 14 second error may not seem like much but over hundreds of years it adds up. By Columbus's time, the vernal equinox was occurring on March 11th instead of March 21st and farmers no longer relied on the calendar for planting and harvesting their crops. In 1582 the Julian calendar was updated and replaced by the Gregorian calendar devised by Pope Gregory XIII.

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Caesar's solar calendar has become the world standard, but in most traditional societies the phases of the moon formed the basis for tracking the passage of time. The problem with a moon-only calendar, however, is that a period of 12 lunar months contains only about 354 days (an average lunation is 29.5 days), which is 11 days less than the 365 days it takes the earth to revolve around the sun. A lunar calendar thus loses time against the actual seasons at a pace of about 11 days each year. To correct this discrepancy, most lunar calendars incorporate a system for inserting extra months, called leap or intercalary months, at fixed intervals. The mathematics, which were worked out by the fifth century B.C. Greek astronomer Meton, produce a figure of seven extra months every 19 years. The Coligny calendar indicates that the ancient Celts employed a 30-year period, over which a total of 11 intercalary months were inserted. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, October 14, 2010]

Gregorian Calendar

Roman calendar Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1585) is the pope who gave us the Gregorian calendar that we use today. When he took over the papacy the Julian calendar was 11 days off out of sync with the seasons.

In 1582, Pope Gregory inaugurated the calendar that would bear his name by ordaining that the day after October 4 was October 15. This aligned the seasons with the calendar but caused an uproar among servants who demanded a full month's wage but were refused it by their employers. The Gregory calendar also started the year on January 1st. To make sure the seasons and dates stayed aligned, leap years were omitted from years marking the beginning of a century. The calendar we follow today is virtually the same as the Gregorian calendar except from time to time top international time keeping bodies add a leap second to ensure that the time kept on earth is aligned with cosmos. ["The Discoveres" by Daniel Boorstien]

As a statement against the power of the Roman church some groups refused to go along with the Gregorian calendar. The eastern Orthodox Church held on to the Julian calendar for its calculations of Eastern Orthodox holidays. Russian didn't stop using the Julian calendar until the Bolshevik revolution in 1917. After the French Revolution, around the same time the metric system was established, the French introduced a day with ten hours, an hour made up of 100 minutes with 100 seconds, and a week consisting of ten days. The time keeping system lasted for 13 years until 1805 when Napoleon brought back the old seve-day-week, 24-hour, 60-second minute system. In 1929 the Soviet Union tried to establish a calendar based on five-day-weeks with one-day weekends that were organized into six-week-months, but by 1940 they too returned to the Gregorian calendar. ["The Discoveres" by Daniel Boorstien]

Gregory decreed that lead days would not be added to in centennial years not divisible by 400. By this criteria 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not leap years but 2000 was. This helped to get rid of an 11-minute a year discrepancy that existed between calendar time and real time.

Romans Months

The original Roman 10-month calendar is source of some confusion among the months: September (now the ninth month) literally means "seventh:" October means "eighth;" November means "ninth" and December means "tenth." Why is December now the “twelfth” month not the "tenth." The answer to that is that in Roman time the year began in March. Back then spring was thought to be a good time to start the new year because it suggested renewal and growth. January and February were added in the 7th century B.C. Two months are named after Roman emperors — July after Julius Caesar and August after Augustus. July was originally called Quintilus and August was called Sextilis.

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The republican calendar (called fasti) divided the ferial days over the course of twelve months. Each month was marked by the calendae (the first day), the nonae, and the idus (the last two fell respectively on the fifth or seventh, and the thirteenth or the fifteenth, according to whether they were ordinary months or March, May, July, or October). The feasts were fixed (stativae) or movable (conceptivae) or organized around some particular circumstance.[Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The month of March contained several feasts marking the opening of martial activities. There was registered on the calendars a sacrifice to the god Mars; the blessing of horses on the Equirria on February 27 and March 14; and the blessing of arms on the Quinquatrus and of trumpets on the Tubilustrium on March 19. In addition, there was the Agonium Martiale on March 17. The Salii, carrying lances (hastae) and shields (ancilia), roamed the city performing martial dances.

Romans Days

Sunday is named for the sun; Monday is named after the moon; Tuesday is named after the Roman god Mars (the Anglo-Saxon god Tiu); Wednesday is named after the Roman god Mercury (the Anglo-Saxon god Woden); Thursday is named after the Roman god Jupiter (the Anglo-Saxon god Thor); Friday is named after the Roman god Jupiter (the Anglo-Saxon god Frigg); Saturday is named after the Roman god Saturn.

Recognized Roman days included Calends (first of each month), the Nones (the fifth or seventh) and the Ides (the thirteenth or fifteenth). The division of the weeks into seven days was making the days subordinate to the seven known planets whose movements were believed to regulate the universe. By the beginning of the third century this usage had become so firmly anchored in the popular consciousness that Dio Cassius considered it specifically Roman. With only one minor modification the substitution of the day of the Lord, dies Dominica (Dimanche), for the day of the Sun. Each the seven days was divided into twenty-four hours which were reckoned to begin, not, as with the Babylonians, at sunrise, nor, as among the Greeks, at sunset, but as is still the case with us, at midnight. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” By Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Calendar days were divided into profane days (dies profesti) and days reserved for the gods (dies festi or feriae), and thus for liturgical celebrations. However, if one looks at a Roman calendar, one observes that the list of days contains other signs. When the days are profane, they are marked by the letter F (fasti) ; when they pertain to the gods, by N (nefasti). This presentation does not call into question the division of "profane" and "sacred" times. It simply changes the perspective as to when "divine" becomes "human." Indeed, for the Romans, the day is fastus when it is fas (religiously licit) to engage in profane occupations, nefastus when it is nefas (religiously prohibited) to do so, since the day belongs to the gods. In reality, the analytical spirit of the pontiffs came up with yet a third category of C days (comitiales), which, while profane, lent themselves in addition to the comitia, or "assemblies." Furthermore, there are other rarely used letters, such as the three dies fissi (half nefasti, half fasti). The dies religiosi (or atri) are outside these categories: they are dates that commemorate public misfortunes, such as July 18, the Dies Alliensis (commemorating the disaster of the battle of Allia in 390 B.C.).

The calendae, often marked by festivals to Juno, were the first day of the month, the nonae, were the ninth day before the ides (accordingly the fifth or seventh day) and the idus fell on the thirteenth or the fifteenth, respectively, according to whether they were ordinary months or March, May, July, or October. The idus were usually dedicated to Jupiter, but the same day staged other important festivals, too. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The term the “dog days” of summer dates back to Roman times when it was observed that during the hottest days of summer the bright star Sirius rose and fell in the constellation Canis Major (the Big Dog).

Length of Hours of the Day in Ancient Rome

The daylight itself was divided into twelve hours (horae); each was one-twelfth of the time between sunrise and sunset and varied therefore in length with the season of the year. “In the same way the hours may be calculated for any given day, if the length of the day and the hour of sunrise are known, but for all practical purposes the old couplet will serve: The English hour you may fix,/ If to the Latin you add six. When the Latin hour is above six it will be more convenient to subtract than to add. The length of the day and hour at Rome at different times of the year is shown in the following table:

Philippi sundial (reconstruction) from Philippi Greece, AD 250-350

At the winter solstice the day hours were as follows:

I. Hora prima from 7.33 to 8.17 A.M.

II. " secunda " 8.17 " 9.02 "

III. " tertia " 9.02 " 9.46 ".

IV. " quarta " 9.46 " 10.31 " V. " quinta " 10.31 " 11.15 "

VI. " sexta " 11.15 " 12.00 noon.

VII. " septima " 12.00 " 12.44 P.M.

VIII. " octava " 12.44 " 1.29 "

IX. " nona " 1.29 " 2.13 "

X. " decima " 2.13 " 2.58 "

XI. " undecima " 2.58 " 3.42 "

XII. " duodecima " 3.42 " 4.27 "

[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

At the summer solstice the day hours ran thus:

I. Hora prima from 4.27 to 5.42 A.M.

II. secunda " 5.42 " 6.58 "

III. " tertia " 6.58 " 8.13 '"

IV. " quarta " 8.13 " 9.29 " V. " quinta " 9.29 " 10.44 "

VI. " sexta " 10.44 " 12.00 noon.

VII. " septima " 12.00 " 1.15 P.M.

VIII. " octava. " 1.15 " 2.31 "

IX. " nona " 2.31 " 3.46 "

X. " decima 3.46 " 5.02 "

XI. " undecima " 5.02 6.17 "

XII. " duodecima " 6.17 " 7.33 "

Month and Day: December 23

Length of Day: 8 hours 54 minutes

Length of Hour: 44 minutes' 30 seconds

[Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Month and Day: February 6

Length of Day: 9 hours 50 minutes

Length of Hour: 49 minutes 10 seconds

Month and Day: March 23

Length of Day: 12 hours 00 minutes

Length of Hour: 1 hour 00 minutes 00 seconds

Month and Day: May 9

Length of Day: 14 hours 10 minutes;

Length of Hour: 1 hours 10 minutes 50 seconds

Month and Day: June 25

Length of Day: 15 hours 6 minutes

Length of Hour: 1 hours 15 minutes 30 seconds

Month and Day: August 10

Length of Day: 14 hours 10 minutes

Length of Hour: 1 hours 10 minutes 50 seconds

Month and Day: September 25

Length of Day: 12 hours 00 minutes;

Length of Hour: 1 hour 00 minutes 00 seconds

Month and Day: November 9

Length of Day: 9 hours 50 minutes;

Length of Hour: 49 minutes 10 seconds

Length of Roman Hours in the Summer and Winter

a replica of the clock of Philippoi

Taking the days of June 25 and December 23 as respectively the longest and shortest of the year, the following table gives the conclusion of each hour for summer and winter:

Sunrise

Summer: 4 hours 27 minutes 00 seconds

Winter: 7 hours 33 minutes 00 seconds

[Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

1st Hour

Summer: 5 hours 42 minutes 30 seconds

Winter: 8 hours 17 minutes 30 seconds

2nd Hour

Summer: 6 hours 58 minutes 00 seconds

Winter: 9 hours 2 minutes 00 seconds

3rd Hour

Summer: 8 hours 13 minutes 30 seconds

Winter: 9 hours 46 minutes 30 seconds

4th Hour

Summer: 9 hours 29 minutes 00 seconds

Winter: 10 hours 31 minutes 00 seconds

5th Hour

Summer: 10 hours 44 minutes 30 seconds

Winter: 11 hours 15 minutes 30 seconds

6th Hour

Summer: 12 hours 00 minutes 00 seconds

Winter: 12 hours 00 minutes 00 seconds

7th Hour

Summer: 1 hours 15 minutes 30 seconds

Winter: 12 hours 44 minutes 30 seconds

8th Hour

Summer: 2 hours 31 minutes 00 seconds

Winter: 1 hours 29 minutes 00 seconds

9th Hour

Summer: 3 hours 46 minutes 30 seconds

Winter: 2 hours 13 minutes 00

10th Hour

Summer: 5 hours 2 minutes 00 seconds

Winter: 2 hours 58 minutes 00 seconds

11th Hour

Summer: 6 hours 17 minutes 30 seconds

3 hours 42 minutes 30 seconds

12th Hour

Summer: 7 hours 33 minutes 00 seconds

Winter: 4 hours 27 minutes 00 seconds

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024