Home | Category: Science and Nature

TIME IN ANCIENT GREECE

Julian Jaynes, a Princeton psychologist, contends that people living when the “ Iliad” was written (the 8th century B.C.) had little awareness of time. The epic poem he says was about people who "did not live in a frame of past happening, who did not have 'lifetimes' in our sense, and who could not reminisce." Concepts of time developed when language advanced to the point where people could describe the past in terms of personal experience. Zeno of Elea, a fifth century B.C. Greek philosopher, was the first man to ponder over the fact that any unit could be subdivided endlessly. [Source "The Enigma of Time" by John Boslough, National Geographic, March 1990]

The 24 hour day, in the words of one historian, "was the result of Hellenistic modification of an Egyptian practice combined with Babylonian numerical procedures." The Egyptian used sun dials and came up with the idea of hours. These hours, in turn, were organized using Babylonian arithmetic which grouped numbers in denominations of six rather than ten (no one knows for sure why the Babylonians selected six). [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

The word "hour" comes from the Latin and Greek words for “season” or “time of day.” It described a twelfth of the period of sunlight or darkness. Minutes (derived from a Latin word for "small part”) were used to divide the region between lines of latitude and mark locations on a circle during ancient times long before they marked time. It wasn’t until perhaps the 13th century, when the mechanical clock was invented, that minutes were used to divide an hour into sixty units. Seconds were not included until the 16th century when clockmaking technology was significantly improved.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SCIENCE IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MATHEMATICS IN ANCIENT GREECE: GEOMETRY, MEASUREMENTS, THEOREMS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ASTRONOMY IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ATOMISTS: LEUCIPPUS AND DEMOCRITUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK TECHNOLOGY factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek and Roman Calendars: Constructions of Time in the Classical World” by Robert Hannah (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Discoverers” by Daniel Boorstin (1985) Amazon.com;

“Time in Antiquity” by Robert Hannah Amazon.com;

“Time and Space in Ancient Greek Thought and Culture” By Steven Cherensky (2024) Amazon.com;

“Time and Cosmos in Greco-Roman Antiquity” by Alexander R. Jones , John Steele, et al. | (2016) Amazon.com;

“Sundials: Their Theory and Construction” by Albert Waugh (1973) Amazon.com;

“Down to the Hour: Short Time in the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East (Time, Astronomy, and Calendars: Texts and Studies” by Kassandra J. Miller (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Timepiece of Shadows: a History of the Sun Dial”

by Henry Spencer Spackman (1895) Amazon.com;

“The Time Museum, Volume I, Time Measuring Instruments; Part 3, Water-clocks, Sand-glasses, Fire-clocks” by Anthony J. Turner (1984) Amazon.com;

“Time Museum Catalogue of the Collection: Time Measuring Instruments, Part 1 : Astrolabes, Astrolabe Related Instruments” (1986) by A. J. Turner Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“The Calendar: The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Holidays” by Mab Borden (2024) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of the Athenians” by H. W. Parke (1977) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of Attica: An Archaeological Commentary” by Erika Simon (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Calendars and Constellations” by Emmeline M. Plunket (1903) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Science” by Liba Taub (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sourcebook in the Mathematics of Ancient Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean”

by Victor J. Katz and Clemency Montelle (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Genesis of Science: The Story of Greek Imagination” by Stephen Bertman (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World” by Charles Freeman (2000) Amazon.com;

“Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle” by G. E. R. Lloyd (1974) Amazon.com;

“Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science – from the Babylonians to the Maya” by Dick Teresi (2010) Amazon.com;

“Technology and Culture in Greek and Roman Antiquity” by S. Cuomo (2007) Amazon.com;

“Technology and Society in the Ancient Greek and Roman Worlds” by Tracey Elizabeth Rihll (2013) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Inventions” by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) Amazon.com;

Years, Months and Days in Ancient Greece

The ancient Greeks had no weeks, nor names for the different days. They followed a 12 month calendar similar to the one used by Babylonians with 29 and 30 day lunar months and a 13th month added on the seventh of thirteen years to ensure that the calendar stayed in sync with the seasons. By contrast, the ancient Egyptians used a 365-day calendar. Each Greek city state added the thirteen month at different times to mark local festivals and suit political needs. A complex system of "intercalculating" was employed to decide on meeting times between citizens of different states and to make arrangements for the pick-up and delivery of goods. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

The Romans developed the idea of the week and gave names to the months. They had an eight-day week which they later changed to seven. By the A.D. third century Romans divided the day into only two parts: before midday “(ante meridiem” A.M.) and after midday (“ post meridiem” P.M.). Someone was in charge of noticing when the sun crossed the meridiem since lawyers were supposed to appear before noon. Later the day was dived into parts: early morning, forenoon, afternoon, and evening and eventually followed a sundial that marked "temporary" hours.

The ancient Greeks had no exact arrangement of days extending from midnight to midnight, with twenty-four hours of equal length, but instead they distinguished between day-time and night-time, calculating from sunrise to sunset, and naturally the length of these periods differed according to the time of year.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

These two chief divisions were again subdivided; first came early morning (from about 6 till 9, if we take the equinoctial periods), the forenoon, when the market-place began to fill (9 to 12), the mid-day heat (12 to 3), and the late afternoon (3 to 6); in the night there was, first, the time when the lamps were lit (6 to 10), next the dead hours of the night (10 to 2), last the dawn (2 to 6). Besides this, they divided the day into twelve equal divisions, the length of which naturally varied according to the length of the day. For this purpose they made use of the sun, which was, of course, only available on cloudless days, though these are by no means infrequent in the south. All these arrangements for measuring the time were probably invented by the Babylonians in very ancient times, and introduced among the Greeks by Anaximander about 500 B.C.

Ancient Greek Sundials

Sundials didn't measure 60 minute hours. Instead they divided the daylight into 12 hours of equal length. Greek sundials looked like inside of the bottom half of a globe. On one side was the pointer that created the shadow and on the other side were lines curving up the side of the globe. These curving lines marked off the hours and compensated for the changing of the sun's position with the seasons. The length of the hours varied from about 45 minutes in the winter time to 75 minutes in the summer. The Greeks called sundials "Hunt-the-Shadow." The Tower of the Winds in Athens had sundials on four sides, which meant an observer could tell the time at any time of the day on three sides of the tower. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

The most primitive is the “shadow-pointer,” which is only a pointed stick fixed in the earth, or a column, or anything else of the kind; the length of the shadow, which varies with the position of the sun, supplied the standard for calculating the hours. The length of the shadow, which changed from morning to evening, made a superficial division of time possible, but it could not fix the time once for all, for all days of the year, but had to be specially calculated according to the changes of the seasons. Twelve divisions of the day, to be determined by the shadow, corresponded with ours only at the equinox; these hours, if we may use the expression, were longer in summer and shorter in winter than our equinoctial hours. This explains why the time of the chief meal, which was usually taken at about five or six in the afternoon, was indicated sometimes by a 7-foot, sometimes by a 10-or 12-foot, or even a 20-foot shadow; for though at midsummer the shadow would be quite small at this time, it would have a considerable length at the equinox, and at the time of the winter solstice it is probable that they did not dine until after sunset. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Unfortunately, we have not sufficient information to determine exactly the length of this shadow-pointer, which was doubtless always the same, in order to prevent confusion. The assumption that the pointer was about the average height of a human being, and that people even used their own shadows for measuring time, is very improbable. Such shadow-pointers probably stood in public places, where everyone could make use of them with help of the lines drawn on the ground; they could only be set up in private dwellings when these had large open spaces (which was not often the case) to which the sun could have access all day long. In later times inventions were made which supplied what was wanting in this mode of reckoning time; lines were graven on the stone floor on which the shadow-pointer stood, which gave, at any rate, some indication of the change in the length of the hours according to the months; a network of lines of this description belonged to the obelisk which Augustus set up on the Campus Martius, and also used as a shadow-pointer.

The sun-dials, invented later than the shadow-pointers, probably by Aristarchus, about 270 B.C., were different; here the shadow of a stick placed in a semicircle, on which the hours were marked by lines, indicated the time of day. There were three kinds: first, those that were calculated at the place on which they were set up, and could not be moved, and which indicated the hours of the day according as they changed in the course of the year; second, those which were arranged for moving, and could be set up at different places; and, third, those used by mathematicians, which showed the equinoctial hours such as we use to-day. It is impossible, however, to determine whether the Greeks were acquainted with all the three kinds which we find in use in the Roman period.

The fifth century B.C. sundial of Meton in Athens consisted of a concave hemisphere of stone, with a horizontal brim, with a pointed metal stylus rising in the center. As soon as the sun entered the hollow of the hemisphere, the shadow of the stylus traced in a reverse direction parallel of the sun.[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Four times a year, at the equinoxes and the solstices, the shadow movements thus obtained were marked by a line incised in the stone; and as the curve of the spring equinox coincided with that of the autumn equinox, three concentric circles were finally obtained, each of which was then divided into twelve equal parts. All that was further needed was to join the corresponding points on the three circles by twelve diverging lines to obtain the twelve hours which punctuated the year's course of the sun as faithfully recorded by the dial. Hence the dial derived its name "hour counter", preserved in the Latin horologium(clock) and in the French horloge. Following the example of Athens, the other Hellenic cities coveted the honor, of possessing sun-dials, and their astronomers proved equal to the task of applying the principle to the position of each.

See Time Under SCIENCE IN ANCIENT GREECE: TIME, MEASUREMENTS, INFLUENCES europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Water Clocks

Water clock in

ancient Agora of Athens

The Greeks used water clocks as the Egyptians had done since the 15th century B.C., Water clocks operate on the principle that water can be made to drip at a fairly constant rate from a bowl with a tiny hole in the bottom. Most Greek water-clocks functioned like hour glasses. They measuring about twenty minutes and were used to limit politician's speeches and the speaking time of accusers and defendants in a court of law. The huge water-clock in the Tower of the Winds not only marked off 24 hours, it showed the seasons and predicted astrological phenomena as well. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

Large water-clocks were rare. They were generally too unwieldy and messy to put in someone's home (water either had to be piped in or someone had to be willing to constantly fill a lot of empty tubs). To be calibrated properly, the flow and the pressure of water had to remain constant. What's more, the lengths of night time hours changed with the season, in opposition to the hours of the day, and this was just too complicated for the Greeks to deal with.∞

There are some example of waterclocks set beside sundials so that time could be ascertained on cloudy days. These clocks still only defined "temporary" hours and the time registered on different clocks varied widely, making it difficult to set appointments. And course they had difficulty dealing with changes in the length of the hours at different times of the year.

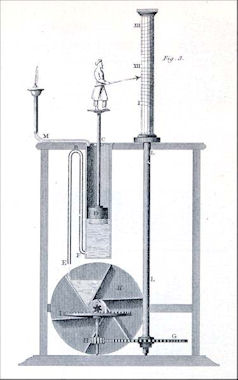

Water Clock of Andronikos Kryrrestos in Athens was an ingenious device built 2000 years ago that was a cross between a toilet and a modern clock. The "mainspring" was a tank fed by a spring that slowly dript water into a barrel which caused a float to rise. The float was connected to series of chains and pulleys that wrapped around a cylinder attached to table-top size disc. When the float rose it caused the chain to move the cylinder which in turn turned the disc. Pointing a finger at the disc was a statue. Hours were indicated by the finger as the disc turned.

Kinds and Uses of Water Clocks in Ancient Greece

There were two kinds of water clock. The common water clock, which, like our hour-glass, marked a definite period of time by the flowing away of a certain quantity of water, is certainly a very ancient invention. This clock consisted of a vessel of clay or glass, in the shape of a jar or a basin, which was filled with water by an opening above, and a second cup-shaped vessel, on the top of which the former was arranged in such a way that the water poured out slowly through little sieve-like openings into the lower vessel. Water clocks of this kind probably existed in most households, but were not real clocks, since they did not indicate the hour of the day, but were only used for calculating some particular period of time. They were chiefly used in the law courts to mark the time allowed to each speaker, and when a speech was interrupted in order to hear witnesses, or to read out documents, or for any other purpose, the flow of the water was stopped, and it was set going again when the orator continued his speech. These water clocks were also used on other occasions wherever certain periods of time had to be calculated, and this might take place in any household.

Clepsydra (water clock)The same principle underlay the water clocks which were supposed to have been invented by Plato, and perfected by the Alexandrine Ctesibius, by means of which a long period of time could be subdivided into equal parts, and thus the hours of the night could be calculated, which was of great importance. These water clocks could only be constructed when it was possible to make transparent glass vessels large enough to hold a quantity of water sufficient to last for twelve hours and longer; on the glass there was a scale graven, which gave the relation of the hours to the height of the water. But as the length of the night decreases and increases in the course of the year, like that of the day, and therefore the length of the night hours is continually decreasing and increasing, a very complicated network of lines was required; four vertical lines denoted the length of the hours at the two solstices and the two equinoxes, so that the exact ratio was given for these days. At other times they had to make shift with a more or less exact calculation, assisted by horizontal curves, which connected together the third, sixth, ninth, and twelfth hours.

The longest and shortest days are here set down according to the latitude of Athens, the former as 14 hours, 36 minutes, 56 seconds, the latter as 9 hours, 14 minutes, 16 seconds. The improvement of Ctesibius consisted in adding a table with horizontal hour-lines to the water-vessel, on which a metal wire, fastened to a cork that swam on the water, marked the time by its position, which rose according to the increase of the water. These clocks could, of course, be used in the daytime, when the weather made the sun-dial useless, but a different scale was required from that of the night clocks. Still, as the difference between the longest night and the longest day, and the shortest night and the shortest day, is very slight, the same scale could really be used for day and night, but in reverse order.

Antikythera Mechanism, the World's First Computer

Antikythera Mechanism The Antikythera Mechanism is the earliest known device to contain an intricate set of gear wheels. It was discovered by sponge divers on a shipwreck of a Greek cargo ship off Antikythera, a Greek island north of Crete, in 1901 but until recently no one knew what it did. Using X-ray tomography, computer models and copies of the actual pieces, scientists from Britain, Greece and the United States were able to reconstruct the device, whose sophistication was far beyond what was though possible for the ancient Greeks.

In November 2006, in an article published in Nature, team of researchers lead by Mike Edmunds of the University of Cardiff announced they had pieced together and figured out of the functions of the Antikythera Mechanism — an ancient astronomical calculator made at the end of the 2nd century B.C. that was so sophisticated it has been described as the world’s first analog computer. The devise was more accurate and complex than any instrument that would appear for the next 1,000 years. [Source: Reuters]

The shoe-box-size device was comprised of a maze 37 hand-cut, interlocking, bronze gear wheels packed together sort of like the gears in a watch and was housed in a wooden case with mysterious inscriptions on the face, cover and bronze dials. Originally thought to be a kind of navigational astrolabe, archaeologists continue to uncover its uses and have come to realize that at the very least is an extremely sophisticated astronomical calendar. Edmunds told Reuters, What is extraordinary is that they were able to make such a sophisticated technological device and be able to put that into metal.” Edmunds said the device is unique and nothing like as sophisticated would appear until the Middle Ages, when the first cathedral clocks were put into use.

See Separate Article: ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM — THE WORLD'S OLDEST COMPUTER europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024