Home | Category: Education, Health, Infrastructure and Transportation

ANCIENT ROMAN AQUEDUCTS

The Romans built over 200 aqueducts in Italy, North Africa, France, Spain, the Middle East, and Turkey. A few of them still carry water today. One Roman official boasted, "Will anybody compare the idle Pyramids . . . to these aqueducts, these many indispensable structures?"

Isabel Rodà wrote in National Geographic History: Aqueducts were costly public works, and not all Roman cities necessarily required them. Some cities, such as Pompeii, had their water needs met by wells or public and private cisterns dug beneath houses. Some cisterns could reach a colossal size, such as the Basilica Cistern (Yerebatan Sarnıcı) in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) and the Piscina Mirabilis in Miseno, Italy. The latter, built to provide drinking water to the Roman navy in the Bay of Naples, had a capacity of just under half a million cubic feet. Its colossal vault is held up by 48 pillars. Some cities needed much more water than cisterns could provide. Booming populations such as Rome’s—thought to have reached one million in the first century A.D.—needed an entire system of aqueducts not only for drinking water but also for supplying ornamental public fountains and baths. [Source Isabel Rodà, National Geographic History, November/December 2016]

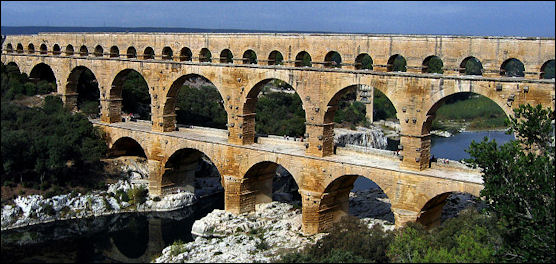

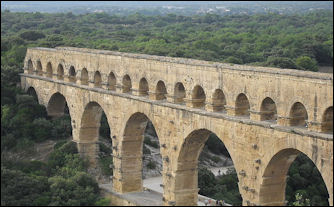

The popular image many people have of an aqueduct is probably something like the spectacular bridge structure of the Pont du Gard in southern France. These aboveground arches were, in fact, only a small section of an aqueduct system. Roman engineers would create a gentle downward slope all the way from start to finish, since the only force powering the water’s progress was gravity. Only valleys or gullies necessitated a monumental arched structure. For most of its route, water ran along underground or ground-level channels. Rome, for example, was supplied by aqueducts totaling 315 miles in length. Of that, 269 miles ran underground and 46 total miles aboveground; however, only about 36 miles consisted of arched structures—just under 12 percent in all.

To such a practical people as the Romans, aqueducts were a source of great pride and even part of their identity. Frontinus made that clear in his treatise on these great public works. “With such an array of indispensable structures carrying so much water, compare, if you will, the idle Pyramids or the useless, though famous, works of the Greeks!”

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN WATER SUPPLY AND SEWERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN INFRASTRUCTURE: BRIDGES, TUNNELS, PORTS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ROADS: CONSTRUCTION, ROUTES AND THE MILITARY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SCIENCE, MEASUREMENT AND TECHNOLOGY IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Aqueducts and Water Supply” by A. Trevor Hodge (2002)

Amazon.com;

“Great Waterworks in Roman Greece: Aqueducts and Monumental Fountain Structures: Function in Context” by Georgia A. Aristodemou and Theodosios P. Tassios (2018) Amazon.com;

“Roman Engineering Genius: Roads, Aqueducts, Baths” by Mariopaolo Fadda (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Aqueducts” by John Henry Parker (1806-1884) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Aqueducts and Fountains” (Classic Reprint) S. Russell Forbes (1885) Amazon.com;

“Roman Engineering Genius: Roads, Aqueducts, Baths” by Mariopaolo Fadda (2023) Amazon.com;

“Water Distribution in Ancient Rome: The Evidence of Frontinus” by Harry B. Evans (1997) Amazon.com;

“Water Displays in Domestic Spaces across the Late Roman West: Cultivating Living Buildings” by Ginny Wheeler (2025) Amazon.com;

“Water in Ancient Mediterranean Households”by Rick Bonnie (Editor), Patrik Klingborg (2025) Amazon.com;

“Bathing in the Roman World” by Fikret Yegül Amazon.com;

“The Essential Roman Baths” by Stephen Bird (2007) Amazon.com;

“Rivers and the Power of Ancient Rome” by Brian Campbell (2012) Amazon.com;

“Engineering in the Ancient World” by J. G. Landels (2000) Amazon.com;

“Roads and Bridges of the Roman Empire” by Horst Barow and Friedrich Ragette (2013)

Amazon.com;

“City: A Story of Roman Planning and Construction” by David Macaulay (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece, and Rome” by Charles Gates and Andrew Goldman (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Construction in Italy from Nerva Through the Antonines” by Marion Elizabeth Blake (1973) Amazon.com;

“Roman Building” by Jean-Pierre Adam (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Different Modes Of Construction Employed In Ancient Roman Buildings And The Periods When Each Was First Introduced” by John Henry Parker (1868) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Concrete Construction in Roman Architecture: Technology and Society in Republican Italy” by Marcello Mogetta (2021) Amazon.com;

“Building for Eternity: The History and Technology of Roman Concrete Engineering in the Sea” by C.J. Brandon, R.L. Hohlfelder, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Architecture” Gene Waddell (2017) Amazon.com;

City of Rome's Aqueducts

A total of 11 aqueducts were built for the city of Rome. They were necessary to keep water flowing into the popular Roman baths and fountains. When Rome was at its height it contained between 1,200 and 1,300 public fountains, 11 great baths, 867 lesser baths, 15 nymphaea (monumental decorated fountains), two artificial lakes for mock naval battles — all kept in operation by some 38 million gallons of water a day brought in by the 11 aqueducts.

Tom Kington wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Rome's emperors had the aqueducts built quickly, employing thousands of slave laborers. In the 1st century, Claudius completed his 60-mile effort in two years. The structures are unusually solid, with cement and crushed pottery used as building material. One of the aqueducts, the Aqua Virgo, is still in use today, keeping Rome parks and even the Trevi fountain supplied. Others were damaged by invading German tribes in the waning days of the empire. The ingenious use of gravity and siphons to accelerate water up slopes has stood the test of time: Aqueducts built in the 20th century to supply Los Angeles with water relied on the same methods.” [Source: Tom Kington, Los Angeles Times, January 1, 2014]

Timeline of the Main Aqueducts in Rome

312 B.C.: The censor Appius Claudius Caecus builds Rome’s first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, which runs almost entirely underground.

144 B.C.: Work begins on Rome’s longest aqueduct, the 56-mile-long Aqua Marcia. The city has doubled in size since the last channel was built.

33 B.C.: After the chaotic civil wars Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) improves Rome’s water by building the Aqua Julia.

19 B.C.: Marcus Agrippa, Augustus’s son-in-law, oversees the building of the Aqua Virgo to supply the thermal baths in the Campus Martius.

A.D. 38-52: Caligula begins a new aqueduct to meet increased demand from baths. Claudius nishes the work and calls it Aqua Claudia.

A.D. 109: Trajan builds the Aqua Traiana, which brings water from near Lake Bracciano to supply Rome’s new suburbs, known today as Trastevere. [Source Isabel Rodà, National Geographic History, November/December 2016]

History of Roman Aqueducts

The Romans didn't make the first aqueducts. The Assyrians built the first aqueducts and paved roads. Aqueducts provided water for lavish gardens that covered the size of football fields. Parts of the most famous pre-Roman aqueducts, built by King Sennacherib for Nineveh around 700 B.C., are still visible in the north of Iraq.

Aqueducts were often built utilizing ancient sources and channels. In the city of Rome The Tepula, named from the temperature of its waters, and completed in 125 B.C., was the last built during the Republic. Under Augustus three more were built, the Julia and the Virgo by Agrippa, and the Alsietina by Augustus, for his naumachia. The Claudia, whose ruined arches are still a magnificent sight near Rome, and the Anio Novus were begun by Caligula and finished by Claudius. The Traiana was built by Trajan in 109 A.D., and the last, the Alexandrina, by Alexander Severus. Eleven aqueducts then served ancient Rome.

Aqueduct-making went into a period of decline after Constantine became emperor and moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Constantinople. After Rome was sacked by the Goths in 537 "Rome went without water for 1,000 years." This was an exaggeration. Rome didn't go without water completely but a lot of materials from aqueducts were looted to make other things.

History of Rome’s Aqueducts

The site of Rome itself was well supplied with water. Springs were abundant, and wells could be sunk to find water at no great depth. Rain water was collected in cisterns, and the water from the Tiber was used. But these sources came to be inadequate, and in 312 B.C. the first of the great aqueducts (aquae) was built by the famous censor, Appius Claudius, and named for him the Aqua Appia. It was eleven miles long, of which all but three hundred feet was underground. This and the Anio Vetus, built forty years later, supplied the lower levels of the city. The first high-level aqueduct, the Marcia, was built by Quintus Marcius Rex, to bring water to the top of the Capitoline Hill, in 140 B.C. Its water was and still is particularly cold and good. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

A section of what is believed to be the Aqua Appia, Rome’s oldest aqueduct, extending more than 100 feet, was uncovered during construction of a new subway line. Rossella Lorenzi wrote in Archaeology magazine: The remains were found near the Colosseum, at around 55 to 60 feet below Piazza Celimontana, a depth usually unreachable by archaeological excavation, says Simona Morretta of the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome. The section of aqueduct measures 6.5 feet tall and is made up of large gray, granular tufa blocks arranged in five rows. “The total absence of any traces of limestone inside the duct suggests that its use over time has been limited,” says Morretta, “or that the structure was abandoned just after a maintenance intervention.” It stretches for more than 100 feet and continues beyond the investigation area bounded by concrete bulkheads. [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2018]

Isabel Rodà wrote in National Geographic History: Aided by his son-in-law Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, Emperor Augustus was particularly active in improving the capital’s water supply, repairing old systems and building new ones. The Augustan-era Aqua Virgo—named, according to legend, for the young girl who directed thirsty soldiers to the springs that fed it—has been used uninterrupted ever since its construction. During his reign, Caligula began building two aqueducts that were finished by Emperor Claudius, the Aqua Claudia and Aqua Anio Novus. Trajan built the Aqua Traiana, which is 37 miles long, in A.D. 109. The last of Rome’s aqueducts was the Aqua Alexandrina, nearly 14 miles long, built by Alexander Severus in A.D. 226. Some have calculated that, once completed, Rome’s aqueducts delivered roughly 1.5 million cubic yards of water per day—about 200 gallons per person. Its water network supplied 11 grand-scale baths, as well as the 900 or so public baths, and almost 1,400 monumental fountains and private swimming pools. [Source Isabel Rodà, National Geographic History, November/December 2016]

aqueduct in Pont du Gard, France

The only Roman aqueduct still functioning today is the Aqua Virgo, known in Italian as Acqua Vergine. Built in 19 B.C. to a plan by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa during the boom in hydrology projects ordered by Augustus. The Virgo was first restored by Pius V in 1570. The springs of the Alexandrina supply the Acqua Felice, built in 1585. The Aqua Traiana was restored as the Acqua Paola in 1611. The famous Marcia was reconstructed in 1870 as the Acqua Pia, or Marcia-Pia.

Aqueduct Building

Roman aqueducts were designed by arcitecti , libratores and paumbarii (hydraulic engineers with different specialties), and built by familia aquaria , or "water family," (educated slave workmen), who were also in charge of guarding the routes and plastering, cleaning, installing and inspecting the lead and terra-cotta pipes. In one report, 7000 workers were employed on a single aqueduct. Archaeologist Guiseppina Satorio told Smithsonian: "Just like a superhighway” they needed “bridges across valleys, tunnels through obstructing hills, curves up and around and down hill to avoid steep changes."

Aqueducts contained "wells" for ventilation and leaked like sieves. As a rule they had a downward slope of five centimeters for every 100 meters of length. Arches were sometimes built to slow water down so it didn't bust the lead tubes that carried the water underground. People illegally tapped into aqueduct pipes and diverted water to their gardens and baths.

Arches or bridges with the aqueduct above ground were built in places where a valley interrupted the aqueduct's route. Early aqueduct bridges consisted of a single tier supported by broad arches. Later double-tiered aqueduct bridges, and even triple tiered ones were built to supplement existing single tier aqueducts or from scratch.

In places where valleys intervened, Romans tried to utilize cheaper alternative to the bridges and arches. Using U-shaped pipelines known as “inverted siphons," they often routed the flow down into a valley and back up again, relying only on the pressure at the receiving end of the pipe to power the water back up the opposite hill. This required the mouth of the pipe where the water emerged to be at a lower elevation than the source. Many major U.S. cities, including New York and Los Angeles, still rely on similar technologies to supply water to their residents. Gravity is still the cheapest and most renewable source of energy; ninety-five percent of the water used in New York is still delivered by gravity. [Source: New York Times]

How a Roman Aqueduct Were Built

Isabel Rodà wrote in National Geographic History: Most of an aqueduct’s course lay underground, along channels that required huge resources and manpower to build. Once the route had been designed, a series of shafts (putei) were dug at intervals of around 230 feet following an ancient Persian technique known as qanat. When the planned depth was reached, construction of the channel or specus began. The shafts were used to carry away dirt in baskets and send down building materials. [Source Isabel Rodà, National Geographic History, November/December 2016]

Isabel Rodà wrote in National Geographic History: Most of an aqueduct’s course lay underground, along channels that required huge resources and manpower to build. Once the route had been designed, a series of shafts (putei) were dug at intervals of around 230 feet following an ancient Persian technique known as qanat. When the planned depth was reached, construction of the channel or specus began. The shafts were used to carry away dirt in baskets and send down building materials. [Source Isabel Rodà, National Geographic History, November/December 2016]

A crane was used to lower stone blocks, which may have been brought from a nearby quarry, to form the lining for the tunnel walls. Depending on the local availability of materials, bricks or concrete were sometimes used for this purpose. The channel was usually waterproofed with a layer of opus signinum, a kind of mortar made of fragments of crushed tiles and amphorae.

Roman piping systems carried water from sources to the city for dozens of miles. The route had to gently slope to allow gravity to carry the water to its destination. Engineers followed the land’s natural grade wherever possible, building channels underground—even if that meant having to make long detours. The Aqua Traiana was a total of 37 miles long, but the distance, as the crow flies, between the spring and Rome was about 31 miles. Only when they had no other choice—when they had to cross a valley or avoid a sudden drop—did they build the spectacular archways, sometimes several stories tall, that dominate the Mediterranean landscape.

Key Elements of Aqueduct Building:

1) Materials: Basic Roman construction materials were stone blocks, concrete, mortar, tiles, and bricks. The structure was faced with a mix of lime and crushed ceramic.

2) Scaffolding: As the construction process advanced, wooden scaffolding was built to aid the workmen, many of whom would have been slaves.

3) Centering: This wooden structure bore the arch’s weight until the last stone was laid. When it was removed, the slotted stones could support their own weight.

4) Arches: Bridges could have two or—less commonly—as many as three tiers of arches. Roman engineers opted for narrow arches, which provided maximum strength.

5) Pillars: Massive pillars, measuring around 10 feet by 10 feet, were required to bear the weight of the arch tiers, and were usually longer at the base of the structure.

6.)Specus: The specus, or water channel, was on the top level of the viaduct and covered with a roof or vault. Sometimes two or more channels were laid on top of one another.

How a Roman Aqueduct Worked

The Romans built aqueducts with a slope of 10 feet for every 3,200 feet of length. When people think of aqueducts, they think of long above-ground arches, but in fact most aqueducts were underground. Of the 270 miles of aqueduct built by the magistrate Frontinus, only 40 miles were above ground. Most aqueducts consisted of tunnels or pipelines with a very shallow downward slope so the water would naturally flow from an elevated source down to the city it supplied. Large aqueducts could supply water for several towns.

aqueduct pipe

Rabun Taylor wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Ancient aqueducts were essentially man-made streams conducting water downhill from the natural sources to the destination. To tap water from a river, often a dam and reservoir were constructed to create an intake for the aqueduct that would not run dry during periods of low water. To capture water from springs, catch basins or springhouses could be built at the points where the water issued from the ground or just below them, connected by short feeder tunnels. Having flowed or filtered into the springhouse from uphill, the water then entered the aqueduct conduit. Scattered springs would require several branch conduits feeding into a main channel. [Source: Rabun Taylor, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 2, March/April 2012]

“If water was brought in from some distance, then care was taken in surveying the territory over which the aqueduct would run to ensure that it would flow at an acceptable gradient for the entire distance. If the water ran at too steep an angle, it would damage the channel over time by scouring action and possibly arrive too low at its destination. If it ran too shallow, then it would stagnate. Roman aqueducts typically tapped springs in hilly regions to ensure a sufficient fall in elevation over the necessary distance. The terrain and the decisions of the engineers determined this distance. Generally, the conduit stayed close to the surface, following the contours of the land, grading slightly downhill along the way. At times, it may have traversed an obstacle, such as a ridge or a valley. If it encountered a ridge, then tunneling was required. If it hit a valley, a bridge would be built, or sometimes a pressurized pipe system, known as an inverted siphon, was installed. Along its path, the vault of the conduit was pierced periodically by vertical manhole shafts to facilitate construction and maintenance.

“Upon arrival at the city’s outskirts, the water reached a large distribution tank called the main castellum. From here, smaller branch conduits ran to various districts in the city, where they met lower secondary castella. These branched again, often with pipes rather than masonry channels, supplying water under pressure to local features, such as fountains, houses, and baths.

Roman Aqueduct System

The channels of the aqueducts were generally built of masonry, for lack of sufficiently strong pipes. Cast-iron pipes the Romans did not have, lead was rarely used for large pipes, and bronze would have been too expensive. Because of this lack, and not because they did not understand the principle of the siphon, high pressure aqueducts were less commonly constructed. To avoid high pressure, the aqueducts that supplied Rome with water, and many others, were built at a very easy slope and frequently carried around hills and valleys, though tunnels and bridges were sometimes used to save distance. The great arches, so impressive in their ruins, were used for comparatively short distances, as most of the channels were underground. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“In the cities the water was carried into distributing reservoirs (castella), from which ran the street mains. Lead pipes (fistulae) carried the water into the houses. These pipes were made of strips of sheet lead with the edges folded together and welded at the joining, thus being pear-shaped rather than round. As these pipes were stamped with the name of the owner and user, the finding of many at Rome in our own time has made it possible to locate the sites of the residences of many distinguished Romans. In Pompeii these pipes can be seen easily now, for in that mild climate they were often laid on the ground close to the house, not buried as in most parts of this country. The poor must have carried the water that they used from the public fountains that were placed at frequent intervals in the streets, where the water ran constantly for all comers.” |+|

“In the cities the water was carried into distributing reservoirs (castella), from which ran the street mains. Lead pipes (fistulae) carried the water into the houses. These pipes were made of strips of sheet lead with the edges folded together and welded at the joining, thus being pear-shaped rather than round. As these pipes were stamped with the name of the owner and user, the finding of many at Rome in our own time has made it possible to locate the sites of the residences of many distinguished Romans. In Pompeii these pipes can be seen easily now, for in that mild climate they were often laid on the ground close to the house, not buried as in most parts of this country. The poor must have carried the water that they used from the public fountains that were placed at frequent intervals in the streets, where the water ran constantly for all comers.” |+|

Each aqueduct in Rome had an elaborate display fountain, with a plaque commemorating the emperor who paid for it. The beautiful fountains built in many Roman cities were largely there for practical rather than decorative purposes. Water that splashed on the pavement and evaporated produced a cooling effect that operated under the same principals as refrigeration. Fountains also relieved the pressure produced by the momentum of water running downhill that was powerful enough to burst pipes.

Funding and Maintenance of Roman Aqueducts

Isabel Rodà wrote in National Geographic History: From planning to completion, building an aqueduct was an extremely costly enterprise, a project for which many Roman cities proudly raised funds. Evidence shows that money often came from both public and private sources. [Source Isabel Rodà, National Geographic History, November/December 2016]

Sometimes aqueducts were paid for by leading citizens. The work was usually carried out as part of their political role. For example, as aedile and consul, Augustus’ son-in-law Agrippa used his own mines to produce the lead pipes that lined the Aqua Julia and Aqua Virgo. From Augustus’ time onward, emperors regularly made donations to the upkeep of this expensive infrastructure.

Among the very few sources to shed light on how aqueducts were built is a Roman funerary monument found at the city of Bejaïa in Algeria. This commemorates the life of one Nonius Datus, an engineer, and recounts the difficulties he encountered in carrying out his work. The long text, written after the aqueduct’s completion around A.D. 152, describes how the city’s inhabitants lobbied for an improved water supply. The process was not as speedy as might have been hoped. Datus planned the aqueduct’s route in around 138. However, the work was not completed until 152, following a series of setbacks, which the monument describes in detail. Most crucially, the teams of workmen who started excavating the two sides of the tunnel did not meet where they were supposed to. On another occasion, bandits attacked the site and Datus escaped by the skin of his teeth, naked, battered, and bruised.

The Roman administration expended huge efforts not just in conveying water, but in maintaining its purity. A large group of specialized workers known as aquarii, ensured the aqueducts’ proper operation and cleanliness. These technicians carried out repairs and systematically cleaned the channels to prevent blockages and maintain a decent water quality. The channel along which the water flowed was always kept covered and tanks called piscinae limariae were placed along the route into which impurities were regularly decanted.

Famous Roman Aqueducts

The first Roman aqueduct, over 16 kilometers miles in length, was built in 313 B.C. from a spring outside Rome to Rome. One of the most magnificent aqueducts was built in 145 B.C. to carry water 90 kilometers from a valley near Tivoli to Rome. Substantial remains of the Aqua Claudia, begun by the emperor Caligula in A.D. 38 and completed by Claudius in A.D. 52, still stand outside of Rome. The aqueduct traveled for more than 60 kilometers from its source and provided the city with an ample water supply.

The world's longest ancient aqueduct was 141 kilometers miles and ran from the springs of Zaghouan to Djebel Djougar in present-day Tunisia. Built by the Romans during the reign of Hadrian (A.D. 117-138), it originally had a capacity of 7 million gallons a day. In 1895, 344 arches still survived. The Aqua Marcia, the third longest of the original 11 aqueducts of Rome, carried spring water 90 miles from east of Rome to the Capitoline hill.

Isabel Rodà wrote in National Geographic History: One of Roman Spain’s most iconic monuments, the Segovia aqueduct is a UNESCO World Heritage site, and one of the best preserved Roman aqueducts in the world. Built to carry water from the Frío River 10 miles away, the structure was traditionally attributed to the emperor Augustus. Recent studies have shown it dates from the period of the emperor Trajan in the first part of the second century A.D. Known by Segovians as El Puente (“the bridge”), the aqueduct features 168 arches. In recent years basins have been found alongside the channel, originally built to filter out the sand carried along from its source. Unlike other aqueduct bridges, plundered for their stone, the Segovia structure has been in almost constant use since its construction, ensuring it has survived intact for nearly 2,000 years. [Source Isabel Rodà, National Geographic History, November/December 2016]

The highest aqueduct bridge is Pont du Gard, in Nimes, France. It still stands today and is about 40 meters (160 feet) tall, the equivalent of a 16-story building. One of the best preserved aqueducts, in Segovia, Spain, still carries fresh water to the city. Both were built over rivers. Pont du Gard has three tiers and is made from blocks of limestone that were pieced together without mortar. The aqueduct took 15 years to build and runs for 50 kilometers between Uzes and Nimes.

According to UNESCO: “The Pont du Gard was built shortly before the Christian era to allow the aqueduct of Nîmes (which is almost 50 kilometers long) to cross the Gard river. The Roman architects and hydraulic engineers who designed this bridge, which stands almost 50 meters high and is on three levels – the longest measuring 275 meters – created a technical as well as an artistic masterpiece.” Henry James wrote: "You are very near it before you see it: the ravine it spans suddenly opens and exhibits the picture.” The three tiers of the monumental bridge he said were "unspeakably imposing."

Aqua Traiana

The Aqua Traiana ("Aqueduct of Trajan" in Latin) was the tenth of Rome’s eleven aqueducts to be built. Rabun Taylor wrote in Archaeology magazine: Around the turn of the second century A.D., the emperor Trajan began construction on a new aqueduct for the city of Rome. At the time, demands on the city's water supply were enormous. In addition to satisfying the utilitarian needs of Rome's one million inhabitants, as well as that of wealthy residents in their rural and suburban villas, water fed impressive public baths and monumental fountains throughout the city. Although the system was already sufficient, the desire to build aqueducts was often more a matter of ideology than absolute need. [Source: Rabun Taylor, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2012]

“Whether responding to genuine necessity or not, a new aqueduct itself was a statement of a city's power, grandeur, and influence in an age when such things mattered greatly. Its creation also glorified its sponsor. Trajan — provoked, in part, by the unfinished projects of his grandiose predecessor, Domitian — seized the opportunity to build his own monumental legacy in the capital: the Aqua Traiana. The aqueduct further burnished the emperor's image by bringing a huge volume of water to two of his other massive projects — the Baths of Trajan, overlooking the Colosseum, and the Naumachia of Trajan, a vast open basin in the Vatican plain surrounded by spectator seating for staged naval battles.

“Upon its completion, the Aqua Traiana was one of the 11 aqueducts that, by the end of the emperor's reign, carried hundreds of millions of gallons of water a day. It was also one of the largest of the aqueducts that sustained the ancient city between 312 B.C., when Rome received its first one, and A.D. 537, when the Goths besieged the city and reportedly cut every conduit outside the city walls. At the time of its dedication in A.D. 109, the Aqua Traiana ran for more than 25 miles, beginning at a cluster of springs on the northwestern side of Lake Bracciano before heading southeast to Rome.

Vast Subterranean Aqueduct in Naples That Served Elite Roman Villas

Outside of Rome, subterranean aqueducts and their paths are much less understood than of those in Rome. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: This knowledge gap included the newly investigated Aqua Augusta, also called the Serino aqueduct, which was built between 30 B.C. and 20 B.C. to connect luxury villas and suburban outposts in the Bay of Naples. Circling Naples and running down to the ancient vacation destination of Pompeii, the Aqua Augusta is known to have covered at least 87 miles (140 kilometers), bringing water to people all along the coast as well as inland. But the complex Aqua Augusta has barely been explored by researchers, making it the least-documented aqueduct in the Roman world. New discoveries earlier this month by the Cocceius Association, a nonprofit group that engages in speleo-archaeological work, are bringing this fascinating aqueduct to light. [Source Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, January 30, 2023]

Thanks to reports from locals who used to explore the tunnels as kids, association members found a branch of the aqueduct that carried drinking water to the hill of Posillipo and to the crescent-shaped island of Nisida. So far, around 2,100 feet (650 meters) of the excellently preserved aqueduct has been found, making it the longest known segment of the Aqua Augusta. Graziano Ferrari, president of the Cocceius Association, told Live Sciencethat "the Augusta channel runs quite near to the surface, so the inner air is good, and strong breezes often run in the passages." Exploring the aqueduct requires considerable caving experience, though. Speleologists' most difficult challenge in exploring the tunnel was to circumvent the tangle of thorns at one entrance.

In a new report, Ferrari and Cocceius Association Vice President Raffaella Lamagna list several scientific studies that can be done now that this stretch of aqueduct has been found. Specifically, they will be able to calculate the ancient water flow with high precision, to learn more about the eruptive sequences that formed the hill of Posillipo, and to study the mineral deposits on the walls of the aqueduct.

Rabun Taylor, a professor of classics at the University of Texas at Austin who was not involved in the report, told Live Science that the newly discovered aqueduct section is interesting because it is "actually a byway that served elite Roman villas, not a city. Multiple demands on this single water source stretched it very thin, requiring careful maintenance and strict rationing." Taylor, an expert on Roman aqueducts, also said the new find "may be able to tell us a lot about the local climate over hundreds of years when the water was flowing." This insight is possible thanks to a thick deposit of lime, a calcium-rich mineral that "accumulates annually like tree rings and can be analyzed isotopically as a proxy for temperature and rainfall," he explained.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024