Home | Category: Science and Philosophy

TECHNOLOGY IN ANCIENT ROME

Roman tower crane Scientific instruments found at Pompeii have included stone sun dials, small portable sun dials made of bone and variety of measuring instruments. Ancient Romans would be familiar with the most of the tools in modern toolbox. The Romans had their version of a plane, bronze folding “ regula” (measuring devices), hand-forged spikes (instead of nails), drills, chains, axes, mattocks, crowbars, handcuffs, combs, heated curling tongs and presses.

The Romans invented revolving human- and animal-powered cage wheels (images of them appear in Pompeii) and developed sophisticated slave- and donkey-powered rotary grain mills. Cage wheels powered cranes that lifted blocks of stone into place during the construction of tall structures. Later similar cranes were use in the construction of medieval cathedrals. The Roman also pioneered the use of ceramics for things like bathtubs and drainage pipes. But for all the genius they never invented or used the wheelbarrow, kites, or cast iron (the Chinese did).

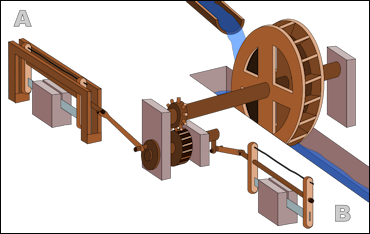

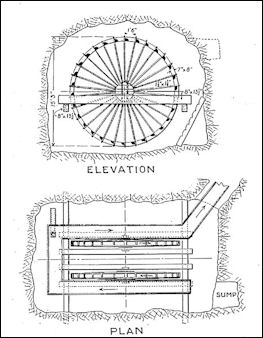

Roman engineers developed upright water wheels of the underwater paddlewheel variety. They used only the horizontal motion of the water, which didn't generate that much power. Water was raised to troughs above a river and waterwheels were used to grind corn. Pumping systems were used in wells and irrigation systems and to pump water out of leaky boats. Sometimes water moving stumps were used to move water considerable distances and heights. In one Roman mine a cascade of eight pairs of scoop wheelers raised water almost a hundred feet.

The Romans also made contributions to undersea technology. Writing in the late first century A.D., Pliny the Elder described Roman divers using snorkel-like apparatuses to stay beneath the sea’s surface. The Romans also invented cement that hardened underwater

RELATED ARTICLES:

SCIENCE IN ANCIENT ROME: MEASURMENTS, NUMBERS, PLINY THE ELDER factsanddetails.com

TIME IN ANCIENT ROME: CALENDARS, SUNDIALS, HOURS europe.factsanddetails.com

ARCHIMEDES AND HIS INVENTIONS europe.factsanddetails.com;

ANCIENT GREEK TECHNOLOGY factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN INFRASTRUCTURE: BRIDGES, TUNNELS, PORTS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN AQUEDUCTS: HISTORY, CONSTRUCTION AND HOW THEY WORKED europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook of Translated Greek and Roman Texts” (Routledge) by Andrew N. Sherwood, Milorad Nikolic, John W. Humphrey Amazon.com;

“Technology and Culture in Greek and Roman Antiquity” by S. Cuomo (2007) Amazon.com;

“Technology and Society in the Ancient Greek and Roman Worlds” by Tracey Elizabeth Rihll (2013) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Inventions” by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) Amazon.com;

“Roman Portable Sundials: The Empire in your Hand” by Richard J.A. Talbert (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Time Museum, Volume I, Time Measuring Instruments; Part 3, Water-clocks, Sand-glasses, Fire-clocks” by Anthony J. Turner (1984) Amazon.com;

“Time Museum Catalogue of the Collection: Time Measuring Instruments, Part 1 : Astrolabes, Astrolabe Related Instruments” (1986) by A. J. Turner Amazon.com;

“London's Roman Tools: Craft, Agriculture and Experience in an Ancient City” by Owen Humphreys (2021) Amazon.com;

“An Essay on the Ancient Weights and Money and the Roman and Greek Liquid Measures”

by Robert Hussey (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Science” by Liba Taub (2020) Amazon.com;

“Intelligence Activities in Ancient Rome: Trust in the Gods but Verify” by Rose Mary Mary Sheldon (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Greece and Rome (Blackwell) by Georgia L. Irby (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek and Roman Science: A Very Short Introduction”

by Liba Taub Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Alchemy in Graeco-Roman Egypt”, Illustrated, by Jack Lindsay (1970) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World” by Roy MacLeod | (2004) Amazon.com;

“Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science – from the Babylonians to the Maya” by Dick Teresi (2010) Amazon.com;

Ancient Inventions

waterwheel Hanna Seariac wrote in the Deseret News: From ice cream to postal services to books to plumbing, the Romans contributed the blueprints for several inventions. Beatrice Silva listed 25 different inventions of the Romans including surgical tools, heating systems, the Julian calendar, public entertainment, cooling systems (think proto-air conditioning), dental fillings, apartments, mass production of glass and other complex systems that are still used or mirrored today. [Source: Hanna Seariac, Deseret News, April 22, 2023]

"Ancient Inventions” is a book by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) is a compendium of curiosities dating from the Stone Age to 1,000 A.D., the book argues that just because our ancestors lived long ago and had less technology at their disposal does not mean they were any less intelligent than we are. In fact, many of the inventions that we believe belong to our own modern era already existed hundreds, sometimes even thousands of years ago. Our ancestors were not quaint superstitious people mystified by the problems of everyday life; they were, much as we are today, hard at work on ingenious solutions. The authors have broken down the inventions into different categories such as medicine; food, drink and drugs; transportation and communications; and military technology, making the book easy to thumb through in the coffee-table style, rather than one to be read from start to finish. [Source: Laura Colby, New York Times, May 16, 1995]

We learn that our ancestors used birth control — everything from a condom to a rudimentary form of the pill — abused drugs ranging from hallucinogenic mushrooms to cocaine, and were entertained by sport, music and theater. We see homes many thousands of years old with plumbing, indoor ovens, and many other conveniences we associate with our own era. But by far the most interesting parts of the book are those that provide examples of technology, rather than everyday objects. Inhabitants of present-day Iraq, for instance, had developed a form of electric battery about 2,000 years ago, using a clay jar that contained a copper rod sealed with asphalt. The so-called Baghdad Battery, discovered in 1936, was probably used by jewelers to electroplate bronze jewelry. Medicine, including brain surgery, the making of artificial limbs and plastic surgery, is one of the most hair-raising chapters. Early military technology, including a "machine gun" in the form of a crossbow that could fire 20 arrows in less than 15 seconds, is also covered.

Reconstructing Roman Machines

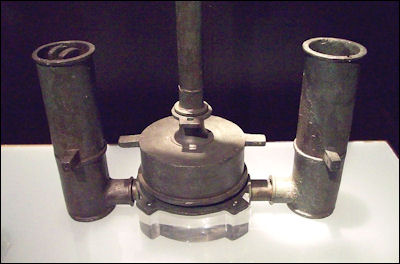

Roman hydraulic pump Adam Hart-Davis wrote for the BBC: “A waterwheel was built by Henry and John Russell in an attempt to copy the remains of a wheel at Dolaucothi in Wales, which appears to have been used to pump water out of the gold mine. The reconstructed wheel was twelve feet high and one foot wide, and when I got it going by walking up the outside like a treadmill, I was able to lift a bathful of water - 150 litres - every minute. According to the experts this is about twice the amount the Romans would have lifted. However, I'm a heavy chap and was only just able to lift this much water. A puny British slave of 1800 years ago certainly would not have been heavy enough. [Source: Adam Hart-Davis, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Therefore it seems likely that the Roman wheel was only about eight inches wide, rather than a foot. Also I could only operate the wheel for a couple of minutes before collapsing for a rest, whereas the slave would probably have been expected to carry on for hours, even in the dark and underground. |::|

“The Russell brothers also built the most wonderful wine press, a Roman fire pump, with which we managed to put out a small fire, and weirdest of all a Roman odometer, to measure the distance travelled along a road. Each time the four-foot wheel turned, it engaged once with a cogwheel carrying 400 teeth. This meant that the big cogwheel rotated exactly once every Roman mile, and at this point a small stone - a calculus - dropped into a box. So at the end of the trip count the calculi and you know how many miles you have covered! |::|

I am amazed at how efficient the Romans were as engineers and organisers. They were not brilliant innovators, and in the 400 years that they occupied Britain they failed to make many technological advances. However, the might of the Roman empire stemmed from the brilliant use they made of the technology they brought with them. And for me, pride of place among the technology must go to that waterwheel at Dolaucothi and those latrines on Hadrian's Wall.” |::|

Iron and Ancient Metallurgy

Pompeii tools Metal was worked in a shaft furnace and shaped with an anvil and hammer, The Greeks made iron stronger by quenching in cold water while the metal was still hot. The Romans learned how to temper it. The Greeks gained access to tin needed to make bronze when they colonized what is now Marseilles.

The Iron Age began around 1,500 B.C. It followed the Stone Age, Copper Age and Bronze Age. North of Alps it was from 800 to 50 B.C. Iron was used in 2000 B.C. Improved iron working from the Hittites became wide spread by 1200 B.C.

Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows.

Iron — a metal a that is harder, stronger and keeps an edge better than bronze — proved to be an ideal material for improving weapons and armor as well as plows (land with soil previously to hard to cultivate was able to be farmed for the first time). Although it is found all over the world, iron was developed after bronze because virtually the only source of pure iron is meteorites and iron ore is much more difficult to smelt (extract the metal from rock) than copper or tin. Some scholars speculate the first iron smelts were built on hills where funnels were used to trap and intensify wind, blowing the fire so it was hot enough to melt the iron. Later bellows were introduced and modern iron making was made possible when the Chinese and later Europeans discovered how to make hotter-burning coke from coal. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Metal making secrets were carefully guarded by the Hittites and the civilizations in Turkey, Iran and Mesopotamia. Iron could not be shaped by cold hammering (like bronze), it had to be constantly reheated and hammered. The best iron has traces of nickel mixed in with it. [Ibid]

About 1200 BC, scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs. Lethal Celtic swords dating back to 950 BC have been found in Austria and its is believed the Greeks learned to make iron weapons from them. [Ibid]

Roman Glass Making

Archscrew Modern glass blowing began in 50 B.C. with the Romans, but origins of glass making go back even further. Pliny the Elder attributed the discovery to Phoenician sailors who placed a sandy pot on some lumps of alkali embalming powder from their ship. This provided the three ingredients needed for glass making: heat, sand and lime. Although it is interesting story, it is far from true.

The Romans made drinking cups, vases, bowls, storage jars, decorative items and other object in a variety of shapes and colors. using blown glass. The Roman, wrote Seneca, read "all the books in Rome" by peering at them through a glass globe. The Romans made sheet glass but never perfected the process partly because windows weren’t considered necessary in the relatively warm Mediterranean climate.

The Romans made a number of advancements, the most notable of which was mold-blown glass, a technique still used today. Developed in the eastern Mediterranean in the 1st century B.C., this new technique allowed glass to be made transparent and in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. It also allowed glass to be mass produced, making glass something that ordinary people could afford as well as the rich. The use of mold-blown glass spread throughout the Roman empire and was influenced by different cultures and arts.

With the core-form mold-blown technique, globs of glass are heated in a furnace until they become glowing orange orbs. Glass threads are wound around a core with a handling piece of metal. Craftsmen then roll, blow and spin the glass to get the shapes they want.

With the casting technique, a mold is formed with a model. The mold is filled with crushed or powdered glass and heated. After cooling down, the plank is removed from the mold, and the interior cavity is drilled and exterior is well cut. With the mosaic glass technique, rods of glass are fused, drawn and cut into canes. These canes are arranged in a mold and heated to make a vessel.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN GLASS europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024