Home | Category: Ethnic Groups and Regions

ROMANS IN SPAIN

When Rome defeated Carthage in the Punic Wars in 146 B.C. it took over Carthage's territories in Spain. The wealth brought in from Spain enabled Rome to finance its conquests elsewhere. Even so the Roman were not able to unify the Iberian peninsula until the first century A.D. According to legend the hill people of Numantia along the Duero refused to bow to he Romans when the invaded in 133 B.C. and committed mass suicide rather than being taken.

The Romans called the Iberian peninsula Hispania. They gave Spain laws, roads, temples, aqueducts and bridges. In return Spain provided Rome with meals, grains, olives, metals and wine. Three of Rome's most influential emperors—Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Auerlius—came from Spain as did the great Roman poet Seneca. Rubén Montoya wrote in National Geographic History: After defeating the Carthaginians in the second century B.C., the Romans controlled the western Mediterranean and the silver mines of southern Spain, whose riches financed the Roman Republic’s ongoing transformation into a huge regional power and later an empire. Among its other important agricultural products, Iberia’s prized olive oil would become a Roman staple, later distributed to every corner of the Roman world. [Source: Rubén Montoya, National Geographic history, April 4, 2024]

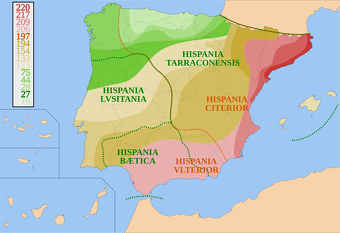

The Romans turned some native cities outside their two provinces into tributary cities and established outposts and Roman colonies to expand their control. Administrative arrangements were ad hoc. Governors who were sent to Hispania tended to act independently from the Senate due to the great distance from Rome. This changed after the end of the Republic and the establishment of rule by emperors in Rome. After the Roman victory in the Cantabrian Wars in the north of the peninsula (the last rebellion against the Romans in Hispania), Augustus conquered the north of Hispania, annexed the whole peninsula and carried out administrative reorganisation in 19 B.C. [Source Wikipedia]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Iberia: Economy, Society and Culture” by Benedict Lowe (2009) Amazon.com;

“Hispania: The Romans in Spain and Portugal” by Michael B Barry (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Occupation of Iberia: The Battles for Hispania, the Jewel in Rome’s Crown”

by J J Herrero Giménez (2025) Amazon.com;

“Wars of the Romans in Iberia” by Appian Amazon.com;

“Late Roman Spain and Its Cities” by Michael Kulikowski (2022) Amazon.com;

“Aristocrats and Statehood in Western Iberia, 300-600 C.E.” by Damián Fernández (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Peasantry in Roman Spain” by Jesús Bermejo Tirado, Ignasi Grau Mira (2022) Amazon.com;

“Carthage: A History” by Serge Lancel (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Vandals” by Simon MacDowall (2019) Amazon.com;

“Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa”

by Andrew Merrills (2016) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Vandals” by Torsten Cumberland Jacobsen (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Late Roman West and the Vandals” by Frank M. Clover (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century: An Ethnographic Perspective” by Peter Heather Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“Race and Ethnicity in the Classical World: An Anthology of Primary Sources in Translation” by Rebecca F. Kennedy , C. Sydnor Roy, et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cultural Identity in the Roman Empire” by Joanne Berry, Ray Laurence (2002) Amazon.com;

by Claire Holleran and April Pudsey (2011) Amazon.com;

“Law in the Roman Provinces (Oxford Studies in Roman Society & Law)

by Kimberley Czajkowski, Benedikt Eckhardt, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

"Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World"

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Migration and Mobility in the Early Roman Empire” by Luuk de Ligt and Laurens Ernst Tacoma (2016) Amazon.com;

Roman Conquest of Spain

The Roman Republic conquered and occupied territories in the Iberian Peninsula that were previously under the control of native Celtic, Iberian, Celtiberian and Aquitanian tribes and the Carthaginian Empire. The Carthaginian territories in the south and east of the peninsula were conquered in 206 B.C. during the Second Punic War. Control was gradually extended over most of the peninsula without annexations. It was completed after the end of the Roman Republic (27 BC), by Augustus, the first Roman emperor, who annexed the whole of the peninsula to the Roman Empire in 19 B.C.) [Source Wikipedia]

The Roman acquisition of the former Carthaginian territories in southern Hispania and along the east coast resulted in an ongoing Roman territorial presence in southern and eastern Hispania. In 197 B.C. the Romans established two Roman provinces: Hispania 1) Citerior (Nearer Spain) along most of the east coast (an area corresponding to the modern Valencia, Catalonia and part of Aragon); and 2) Hispania Ulterior (Further Spain) in the south, corresponding to modern Andalusia.

Over the next 170 years, the Republic expanded its control over Hispania. This was a gradual process of economic, diplomatic and cultural infiltration and colonization, with campaigns of military suppression when there was native resistance, rather than the result of a single policy of conquest.

Roman Sites in Spain

Barcelona began as a Roman colony and became a great Mediterranean trading center in the Middle Ages. Tarragona (65 miles southwest of Barcelona) was taken by the Romans from the Carthiginians in 218 B.C. and later became the Roman capital of Spain. Tarragona was used as resort by Roman emperors and was described by Pliny and Martial. The Roman ruins include various parts of an aqueduct, Palace of Augustus, Triumphal Arch of Bara, Praetorium, amphitheater and Scipio's tower. The archeology museum houses Romans items such as mosaics, statues, household implements and coins from excavations in the Tarragona area. The Archeologic Passeig is a pathway that follows the city's ancient wall, which is composed boulders placed by pre-Iberian civilizations, Roman and Augustinian improvements, Moorish and Visigoth towers and windows and buildings from the Middle Ages. Ampurias is the Costa Brave resort is where visitors can explore excavations of a 5th century Greek settlement B.C. and a Roman city dating back to the second and third centuries A.D.

Toledo was first settled by the Romans in the 3rd century A.D. They liked its strategic and easily defeasible position. Later it was capital city of the Visigoths. Outside the city is the Alcantara Bridge, a dramatic structure first built by Romans between two high cliffs over the Tajo River

Leon (200 miles northwest of Spain) is an ancient city that was founded by the Romans in the first century A.D. The Plata Road is a 500-mile Roman trail that begins in Gijon in northern Spain and ends in Seville. Built in the first century A.D. to transport minerals from the western Iberian mountains, it passes by Roman ruins and medieval monuments and connects Leon, Salamanca, Cáceras and Mérida.

Segovia (55 miles northwest from Madrid) is famous for its Roman aqueduct, a 2000-year-old structure used up until only a few years ago, It begins 14 miles from the city at the Puenta Alta reservoir and runs right through the middle of town. The best place to see the arched aqueduct is at Plaza Azoquejo where it towers nearly 100 feet over the city. One section of the aqueduct connects two hills and spans a distance of 1,800 feet with 148 arches. It is one of the best preserved Roman aqueducts in the world.

Cádiz is the oldest continually inhabited town in Western Europe. Founded by the Phoenicians, it was an important town during the Roman era and the Age of Discovery. The Galican peninsula was called Finis Terrare by the Romans who believed it was to be westernmost point of land in the world. Merida in Extremadura contains one of the world's best preserved Roman theaters. During the summer the 6,000-seat theater hosts a drama festival. Nine miles outside of Seville are the ruins of the Roman colony Italica. Founded by the legendary Roman general Scipio, it was the birthplace of the three Roman emperors, including Hadrian. The Roman amphitheater is very lovely.

Hannibal Marches His Elephants from Spain Over the Alps in the Punic Wars

In 218 B.C., Hannibal left his base in base in Spain and led a force of mercenaries with elephants through the south of Gaul (France) and across the Alps in the winter. This marked the beginning of the Second Punic War. The elephants had little impact on the fight but they scored a psychological blow for the Carthaginians giving them an aura of power and invincibility.

Rome began to be alarmed when Carthage began extending its territory toward the north from southern Spain.. Rome induced Carthage to make a treaty not to extend her conquests beyond the river Iberus (Ebro), in the northern part of Spain. Rome also formed a treaty of alliance with the Greek city of Saguntum, which, though south of the Iberus, was up to this time free and independent. Carthage continued the work of conquering the southern part of Spain, without infringing upon the rights of Rome, until Hasdrubal died. Then Hannibal, the young son of the great Hamilcar, and the idol of the army, was chosen as commander. This young Carthaginian, who had in his boyhood sworn an eternal hostility to Rome, now felt that his mission was come. He marched from New Carthage and proceeded to attack Saguntum, the ally of Rome; and after a siege of eight months, captured it. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Hannibal's father Hasdrubal had (together with his father-in-law Hamilcar) began the conquest of Spain in the south, supposedly with his little boy (Hannibal) at his side. When Hamilcar died in 228 Hasdrubal took over the war effort. When Hasdrubal died in 221, the 21 year old Hannibal took over. The climax of his pushes to the west and north was the successful assault on Saguntum, which occurred while Rome was busy in Illyria. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

PUNIC WARS AND HANNIBAL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): ROME AND CARTHAGE BATTLE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND SICILY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): CARTHAGE SUCCESSES, ULTIMATE ROMAN VICTORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL: HIS LIFE, ACHIEVEMENTS AGAINST ROME, EXILE, DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS: ELEPHANTS, POSSIBLE ROUTES AND HOW HE DID IT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CARTHAGE VICTORIES IN THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THIRD PUNIC WAR: ROME DECISIVELY DEFEATS CARTHAGE europe.factsanddetails.com

Pacification of Spain

Vandals

After the second Punic war, Spain was divided into two provinces, each under a Roman governor. But the Roman authority was not well established in Spain, except upon the eastern coast. The tribes in the interior and on the western coast were nearly always in a state of revolt. The most rebellious of these tribes were the Lusitanians in the west, in what is now Portugal; and the Celtiberians in the interior, south of the Iberus River. In their efforts to subdue these barbarous peoples, the Romans were themselves too often led to adopt the barbarous methods of deceit and treachery. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

War with the Lusitanians (155 to 139 B.C.): How perfidious a Roman general could be, we may learn from the way in which Sulpicius Galba waged war with the Lusitanians (an Indo-European people living in the west of the Iberian Peninsula prior to its conquest by the Roman Republic).. After one Roman army had been defeated, Galba persuaded this tribe to submit and promised to settle them upon fertile lands. When the Lusitanians came to him unarmed to receive their expected reward, they were surrounded and murdered by the troops of Galba. But it is to the credit of Rome that Galba was denounced for this treacherous act. Among the few men who escaped from the massacre of Galba was a young shepherd by the name of Viriathus. Under his brave leadership, the Lusitanians continued the war for nine years. Finally, Viriathus was murdered by his own soldiers, who were bribed to do this treacherous act by the Roman general. With their leader lost, the Lusitanians were obliged to submit (138 B.C.). \~\

Numantine War (143–133 B.C.): The other troublesome tribe in Spain was the Celtiberians, who were even more warlike than the Lusitanians. At one time the Roman general was defeated and obliged to sign a treaty of peace, acknowledging the independence of the Spanish tribe. But the senate—repeating what it had done many years before, after the battle of the Caudine Forks—refused to ratify this treaty, and surrendered the Roman commander to the enemy. The “fiery war,” as it was called, still continued and became at last centered about Numantia, the chief town of the Celtiberians. The defense of Numantia, like that of Carthage, was heroic and desperate. Its fate was also like that of Carthage. It was compelled to surrender (133 B.C.) to the same Scipio Aemilianus. Its people were sold into slavery, and the town itself was blotted from the earth. \~\

Revolt in Spain Leads to Nero's Death

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In A.D. 68, one of the governors of what is now France rebelled in response to Nero’s tax policies. While his rebellion was crushed it triggered a more widespread sense of dissatisfaction and unease among the ruling class. Galba, the governor of part of modern Spain, also rebelled and, despite being declared a public enemy, won the support of Nero’s bodyguards. With his military support turned against him, Nero knew he was in trouble. He toyed with the idea of raising troops from some of the Eastern Provinces or throwing himself at Galba’s mercy, but in the end he fled to the villa of one of his imperial freedmen with a cluster of loyal freedmen (including Sporus) in tow. Nero ordered them to dig a grave for him. He couldn’t quite summon up the courage to kill himself so, in the end, he tasked his former secretary, Epaphroditus, with helping him. He was 30 years old. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 24, 2022]

Suetonius wrote: “Thereafter, having learned that Galba also and the Spanish provinces had revolted, he fainted and lay for a long time insensible, without a word and all but dead. When he came to himself, he rent his robe and beat his brow, declaring that it was all over with him; and when his old nurse tried to comfort him by reminding him that similar evils had befallen other princes before him, he declared that unlike all others he was suffering the unheard of and unparalleled fate of losing the supreme power while he still lived. Nevertheless he did not abandon or amend his slothful and luxurious habits; on the contrary, whenever any good news came from the provinces, he not only gave lavish feasts, but even ridiculed the leaders of the revolt in verses set to wanton music, which have since become public, and accompanied them with gestures; then secretly entering the audience room of the theater, he sent word to an actor who was making a hit that he was taking advantage of the emperor's busy days. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

After the revolt, Nero killed himself on in June, 68 A.D. at the age of 30 a few miles outside of the city of Rome by falling on his sword. Moss wrote: Nero fled Rome and was declared a public enemy of the state. Fearing the wrath of the Senate and concerned that a gruesome end awaited him, Nero had his secretary help him commit suicide. It turns out committed suicide unnecessarily to avoid what he thought was a public execution at the hands of the Roman Senate (they were actually trying to work out a compromise). [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 21, 2021]

Riotinto Mines in Spain

For 5,000 years what today are known as the Riotinto Mines in southwestern Spain produced wealth that sustained civilizations, riches that created cash economies and pollution that spread around the globe. Barry Yeoman wrote in Archaeology Magazine, “Riotinto is part of the Iberian Pyrite Belt, a mineral deposit that stretches from Spain into Portugal. It is one of the largest known mining complexes in the ancient world. Starting as a surface operation focused on copper minerals, it eventually became an industrial-scale enterprise until it finally closed in 2001 amid falling copper prices. [Source: Barry Yeoman, Archaeology Magazine, September-October 2010]

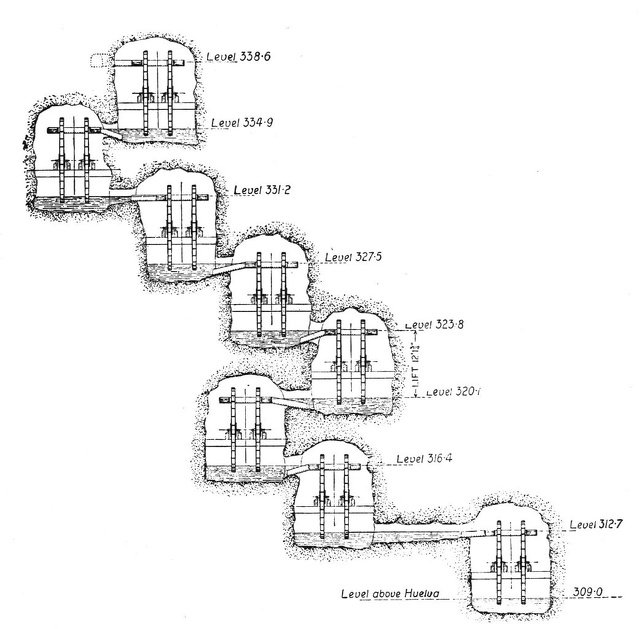

“The Romans took over Riotinto in 206 B.C. after defeating and expelling the Carthaginians, who had occupied the region since about 535 B.C. With the technical knowledge of Rome's military engineers and the availability of slave and convict labor, the Roman operations at Riotinto grew colossally, peaking from A.D. 70 to 180. Their magnitude far exceeded anything that came before. During that period, Riotinto was the largest silver and copper mining operation in the Roman Empire.

The Romans mined Riotinto by digging shafts of up to 450 feet deep, which required elaborate ventilation and drainage systems, including wooden water wheels and a system of gently sloping drainage channels that remained in use well into the 20th century. They also developed a sophisticated system of governance. Two bronze tablets unearthed at Aljustrel, another Pyrite Belt mine across the Portuguese border, spelled out the rules by which the Roman government would lease Iberia's mines to individual conductores , who paid 50 percent commission on the ore they excavated. The tablets, discovered in 1876 and 1906, also covered mine safety, the treatment of slaves, and the granting of concessions to barbers, auctioneers, and cobblers. Bathhouse owners, who bought franchises, had to keep the water heated year-round, polish the metalwork every month, and admit women and men at specific hours.

See Separate Article: RIOTINTO, MINING AND RESOURCES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Archaeological Discoveries from Roman-Era Spain

Archaeology magazine reported: Roman oil amphoras were frequently marked with information specifying their contents or manufacturer. Thus, an 1,800-year-old ceramic amphora fragment from Hornachuelos, Córdoba, etched with writing was originally considered nothing special. However, closer examination revealed it had been engraved with two verses of a poem written by Virgil, the first time any works of Rome’s most celebrated poet have been found on an amphora. Fittingly, the lines were taken from Virgil’s Georgics, a work dedicated to agriculture and rural life. [Source: archaeology magazine, September 2023]

Archaeologists working at the Roman villa site of Los Villaricos near the town of Mula uncovered an ornate Visigothic sarcophagus. The villa was repurposed into a Christian basilica and necropolis in the 6th century A.D. after the Germanic Visigoths invaded the Iberian Peninsula. The lid of the 6.5-foot sarcophagus is decorated with geometric patterns and ivy leaves. It is also etched with a popular early Christian symbol, the Christogram, which combines the first two Greek letters of Christ’s name, X (chi) and P (rho). [Source: Archaeology magazine, November 2021]

While digging in a large Roman house in the Spanish city of Mérida, archaeologists uncovered a vibrant mosaic featuring geometric and plant motifs, depictions of fish and animals, and, at its center, the head of Medusa. The mosaic covered the floor of a room measuring about 20 by 30 feet that had colorful painted walls. “Because of its location, we believe that this space was the tablinum, one of the main rooms of the house, where the owner received his guests,” says Félix Palma García, director of the Consortium of the Monumental City of Mérida. [Source: Benjamin LEONARD, Archaeology magazine

Images of theatrical masks, a panther, and four peacocks frame Medusa. These symbols are associated with the god Dionysus, according to art historian Irene Mañas of the National University of Distance Education. Such mythological motifs were common domestic decorations in the late second or early third century A.D., when the mosaic was created. “The mosaic’s symbols and allusions have a protective sense,” Mañas says. “Medusa is an apotropaic image that would have protected the house’s inhabitants from the gaze of the envious.”

Roman Basement Baths in Toledo

According to the Miami Herald: Tucked along the corner of two narrow streets in Toledo sits a colorful house. Archaeologists excavated the house’s basement and uncovered the ruins of a large Roman bath house constructed in the second century A.D., the Toledo Consortium said. Excavations of the bath house have unearthed a two-floored complex, the city said in an earlier release. The ruins reached about 20 feet below the modern building and had been buried for centuries. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, March 10, 2023]

Archaeologists found several cold water pools, also called frigidarium, on the top floor and service galleries on the lower floor. The lower galleries functioned as a kind of network where workers would pass through without being seen by bathers, experts said. The workers would add fuel to and clean out the ovens that heated the pools up above as well as manage the water levels in the pools. Some of these supply pipes — both for water and sewage — were uncovered among the ruins. A column base, decorative marble architecture fragments and highly valuable ceramics were also found below the house, archaeologists said.

Deep beneath an ancient Spanish church, a set of tunnels has long been a source of curiosity. The three tunnels make a U-shape underneath the church of the convent of Sant Agustí in Castelló d’Empúries, experts with the Institut d’Estudis Empordanesos said. Combined, they are about 130 feet long, 10 feet wide and 15 feet high. Archaeologists said the tunnels were made of opus signinum — a simple, unpatterned pavement commonly used by the Romans — and had a hydraulic mortar coating, indicating that they may have been used as cisterns for holding water. Experts estimate that altogether the tunnels could hold more than 100,000 gallons of water. Using a sample of coal from the tunnels to conduct a radiocarbon analysis, experts determined the tunnels were built between 198 B.C. and 42 B.C., which was during the Roman Republic — and much earlier than what archaeologists expected. [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, March 3, 2023]

During this time, the Romans used Castelló d’Empúries as a port and colony in Iberia. In 195 B.C., the Iberians revolted before Roman armies led by Marcus Porcius Cato stopped them. Following this defeat, the region saw a period of heavy military presence, experts at the institute said. This led to increased construction of castles, towers, residences, offices and more. The tunnels remained in use through the 20th century, offering protection during wars, according to the archaeologists. Castelló d’Empúries is on the northeast coast of Spain, about 90 miles northeast of Barcelona.

Vandals, Visigoths and Spain After the End of the Roman Empire

In the A.D. 5th century,. Rome was sacked twice: first by the Visigoths in 410 and then the Vandals in 455. The final blow came in 476, when the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustus, was forced to abdicate and the Germanic general Odoacer took control of the city. Italy eventually became a Germanic Ostrogoth kingdom. The historian Adrian Goldsworthy wrote that the barbarian invaders “struck at a body made vulnerable by prolonged decay." After the collapse of the Roman empire, ethnic chiefs and kings, ex-Roman governors, generals, war lords, peasant leaders and bandits carved up the former Roman provinces into feudal kingdoms. Feudalism after the Roman occupation was more controlled and structured than the loose form of feudalism that existed before the Romans arrived. Peasants were permanently assigned to "manorial estates." They provided food and labor to the aristocratic class of lords and knights in return for protection from bandits and rival kingdoms.

After the fall of Rome in the A.D. 5th century, Spain was invaded by the Vandal, Suevi and Alan tribes, who carved up the Iberian peninsula with the Vandals claiming the largest chunk. The Vandals were displaced by a Visagoth a branch of the Goths, the first Teutonic people to be Christianized. Originally from Scandinavia, the Goths migrated from Sweden across the Baltic Sea, through what is now Russia and the Ukraine to the Black Sea. From there they migrated into the Balkans and divided into two groups the Otsrogoths (East Goths) and Visagoths (West Goths).

Before their division the Goths were allowed by the Romans to settle within the borders of the Roman Empire. They rose against the Romans and killed the Roman emperor Valentinian in battle. His successor was Theodosius, a Spaniard and the last ruler of undivided Rome. He sued for peace and allowed the Visagoths to move into Spain ad drive out the Vandals.

The Germanic Visagoths, many of them probably with blonde hair and blue eyes, established an empire in Spain that lasted for around 300 years. The Visigoth kingdoms of Spain (from 419) and France (from 507) retained Roman administration and law. The Visigoth kingdom saw a continuation of Roman administration until it was destroyed by the Muslims in 711.

Vandals and Visagoths

The Vandals were a group of German pirates who were originally from the Baltic area. They ravaged Gaul and Spain and settled along both the northern and southern Mediterranean coast in Spain and North Africa. They were known for looting churches and trashing art objects. They were so notorious they gave birth to the term “vandals.

Visigoth King Alaric I entering Athens

The Roman provinces in North Africa was taken between A.D. 429-39 by local tribes and Vandals who had migrated there from Europe. The Vandals established their capital in Carthage, built a fleet of ships and attacked the Roman territory and harassed Roman shipping in the Mediterranean between 439-534 from positions in northern Africa.

The Vandals who had fought under Radagaisus had, upon the death of that leader, retreated into Spain, and had finally crossed over into Africa, where they had erected a kingdom under their chief Genseric. They captured the Roman city of Carthage and made it their capital; and they soon obtained control of the western Mediterranean. On the pretext of settling a quarrel at Rome, Genseric landed his army at the port of Ostia, took possession of the city of Rome, and for fourteen days made it the subject of pillage (A.D. 455). By this act of Genseric, the city lost its treasures and many of its works of art, and the word “vandalism” came to be a term of odious meaning. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)\~]

In the A.D. 5th century, Spain was invaded by the Vandal, Suevi and Alan tribes, who carved up the Iberian peninsula with the Vandals claiming the largest chunk. Later the Vandals were displaced by a Visagoth a branch of the Goths, the first Teutonic people to be Christianized. Originally from Scandinavia, the Goths migrated from Sweden across the Baltic Sea, through what is now Russia and the Ukraine to the Black Sea. From there they migrated into the Balkans and divided into two groups the Otsrogoths (East Goths) and Visagoths (West Goths).

Before their division the Goths were allowed by the Romans to settle within the borders of the Roman Empire. They rose against the Romans and killed the Roman emperor Valentinian in battle. His successor was Theodosius, a Spaniard and the last ruler of undivided Rome. He sued for peace and allowed the Visagoths to move into Spain and drive out the Vandals. The Germanic Visagoths, many of them perhaps with blonde hair and blue eyes, established an empire in Spain that lasted for around 300 years.

Visigothic King

(Caius) Sollius Apollinaris (Modestus)Sidonius, (A.D. c.431-c.489) was a Roman Aristocrat living in Gaul at the time of its transformation from a province of the Roman Empire to the property of Frankish Kings. His letters are among the prime documents of the period. The two letters here illustrate aspects of that experience. The first is an account of the possibility of an idyllic country life for the Gallo-Roman aristocracy of the fifth century: the Roman Empire ended, but not, immediately, the lifestyle. The second is a description of a Germanic King, in this case Theodoric II, King of the Visigoths 453-66 [note: not the same as the Ostrogothic Theodoric!]. We see here the ways in which the Gallo-Roman aristocracy began to accommodate itself to the new military powers.

Sidonius wrote to his brother-in-law Agricola (A.D. 454?): “You have often begged a description of Theodoric the Gothic king, whose gentle breeding fame commends to every nation; you want him in his quantity and quality, in his person, and the manner of his existence. I gladly accede, as far as the limits of my page allow, and highly approve so fine and ingenuous a curiosity. [Source: Sidonius Apollinaris (c. A.D. 431-c.489), “The Letters of Sidonius,” Book I, Letter II, translated by O.M. Dalton, (Oxford: Clarendon, 1915), two vols]

Visigoth king Gesaleic

“Well, he is a man worth knowing, even by those who cannot enjoy his close acquaintance, so happily have Providence and Nature joined to endow him with the perfect gifts of fortune; his way of life is such that not even the envy which lies in wait for kings can rob him of his proper praise. And first as to his person. He is well set up, in height above the average man, but below the giant. His head is round, with curled hair retreating somewhat from brow to crown. His nervous neck is free from disfiguring knots. The eyebrows are bushy and arched; when the lids droop, the lashes reach almost half-way down the cheeks. The upper ears are buried under overlying locks, after the fashion of his race. The nose is finely aquiline; the lips are thin and not enlarged by undue distension of the mouth. Every day the hair springing from his nostrils is cut back; that on the face springs thick from the hollow of the temples, but the razor has not yet come upon his cheek, and his barber is assiduous in eradicating the rich growth on the lower part of the face.2 Chin, throat, and neck are full, but not fat, and all of fair complexion ; seen close, their colour is fresh as that of youth; they often flush, but from modesty, and not from anger. His shoulders are smooth, the upper- and forearms strong and hard ; hands broad, breast prominent; waist receding. The spine dividing the broad expanse of back does not project, and you can see the springing of the ribs ; the sides swell with salient muscle, the well-girt flanks are full of vigour. His thighs are like hard horn ; the knee-joints firm and masculine; the knees themselves the comeliest and least wrinkled in the world. A full ankle supports the leg, and the foot is small to bear such mighty limbs.

“Now for the routine of his public life. Before daybreak he goes with a very small suite to attend the service of his priests. He prays with assiduity, but, if I may speak in confidence, one may suspect more of habit than conviction in this piety. Administrative duties of the kingdom take up the rest of the morning. Armed nobles stand about the royal seat; the mass of guards in their garb of skins are admitted that they may be within call, but kept at the threshold for quiet's sake; only a murmur of them comes in from their post at the doors, between the curtain and the outer barrier.1 And now the foreign envoys are introduced. The king hears them out, and says little ; if a thing needs more discussion he puts it off, but accelerates matters ripe for dispatch. The second hour arrives ; he rises from the throne to inspect his treasure-chamber or stable. If the chase is the order of the day, he joins it, but never carries his bow at his side, considering this derogatory to royal state. When a bird or beast is marked for him, or happens to cross his path, he puts his hand behind his back and takes the bow from a page with the string all hanging loose; for as he deems it a boy's trick to bear it in a quiver, so he holds it effeminate to receive the weapon ready strung. When it is given him, he sometimes holds it in both hands and bends the extremities towards each other ; at others he sets it, knot-end downward, against his lifted heel, and runs his finger up the slack and wavering string. After that, he takes his arrows, adjusts, and lets fly. He will ask you beforehand what you would like him to transfix ; you choose, and be hits. If there is a miss through either's error, your vision will mostly be at fault, and not the archer's skill. On ordinary days, his table resembles that of a private person. The board does not groan beneath a mass of dull and unpolished silver set on by panting servitors; the weight lies rather in the conversation than in the plate ; there is either sensible talk or none. The hangings and draperies used on these occasions are sometimes of purple silk, sometimes only of linen; art, not costliness, commends the fare, as spotlessness rather than bulk the silver. Toasts are few, and you will oftener see a thirsty guest impatient, than a full one refusing cup or bowl. In short, you will find elegance of Greece, good cheer of Gaul, Italian nimbleness, the state of public banquets with the attentive service of a private table, and everywhere the discipline of a king's house. What need for me to describe the pomp of his feast days ? No man is so unknown as not to know of them. But to my theme again.

The siesta after dinner is always slight, and sometimes intermitted. When inclined for the board-game, he is quick to gather up the dice, examines them with care, shakes the box with expert hand, throws rapidly, humorously apostrophizes them, and patiently waits the issue. Silent at a good throw, he makes merry over a bad, annoyed by neither fortune, and always the philosopher. He is too proud to ask or to refuse a revenge; he disdains to avail himself of one if offered; and if it is opposed will quietly go on playing. You effect recovery of your men without obstruction on his side; he recovers his without collusion upon yours. You see the strategist when be moves the pieces ; his one thought is victory. Yet at play he puts off a little of his kingly rigour, inciting all to good fellowship and the freedom of the game: I think he is afraid of being feared. Vexation in the man whom he beats delights him; he will never believe that his opponents have not let him win unless their annoyance proves him really victor. You would be surprised how often the pleasure born of these little happenings may favour the march of great affairs. Petitions that some wrecked influence had left derelict come unexpectedly to port; I myself am gladly beaten by him when I have a favour to ask, since the loss of my game may mean the gaining of my cause. About the ninth hour, the burden of government begins again. Back come the importunates, back the ushers to remove them ; on all sides buzz the voices of petitioners, a sound which lasts till evening, and does not diminish till interrupted by the royal repast ; even then they only disperse to attend their various patrons among the courtiers, and are astir till bedtime.

“Sometimes, though this is rare, supper is enlivened by sallies of mimes, but no guest is ever exposed to the wound of a biting tongue. Withal there is no noise of hydraulic organ, or choir with its conductor intoning a set piece ; you will hear no players of lyre or flute, no master of the music, no girls with cithara or tabor; the king cares for no strains but those which no less charm the mind with virtue than the ear with melody. When he rises to withdraw, the treasury watch begins its vigil; armed sentries stand on guard during the first hours of slumber. But I am wandering from my subject. I never promised awhole chapter on the kingdom, but a few words about the king. I must stay my pen ; you asked for nothing more than one or two facts about the person and the tastes of Theodoric; and my own aim was to write a letter, not a history. Farewell.”

See Stuff Under the Western Empire in NOTITIA DIGNITATUM (REGISTER OF DIGNITARIES) europe.factsanddetails.com ; LOCAL AND PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024