Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.)

HANNIBAL

Hannibal Hannibal (247-183 B.C.) was a cagey strategist who came close to destroying Rome through his military skill and cheeky audacity. He played a pivotal role in one the greatest what-if moments in world history. Napoleon regarded Hannibal as the greatest military man of antiquity. Not only did he outmaneuver the great Roman legions, he managed the logistics of getting his army through the Alps to surprise Rome. Hannibal came within a whisker of defeating Rome. If he had won the world might have had a more difficult time spelling a Carthaginian Empire than a Roman one.

Hannibal was the son of Hamilcar Barca. Hamilcar Barca rebuilt Carthage after the first Punic War. Lacking the means to rebuild the Carthaginian fleet he built an army in Spain. Before taking power, Hannibal was reportedly required by his father to forever be an enemy of Rome. Reportedly he stood before an altar and swore: “I will follow the Romans both at sea and on land. I will use fire and metal to arrest the destiny of Rome.

Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “The Histories”: “Of all that befell the Romans and Carthaginians, good or bad, the cause was one man and one mind — Hannibal. For it is notorious that he managed the Italian campaigns in person, and the Spanish by the agency of the elder of his brothers, Hasdrubal, and subsequently by that of Mago, the leaders who killed the two Roman generals in Spain about the same time. Again, he conducted the Sicilian campaign first through Hippocrates and afterwards through Myttonus the Libyan. So also in Greece and Illyria: and, by brandishing before their faces the dangers arising from these latter places, he was enabled to distract the attention of the Romans thanks to his understanding with King Philip [Philip V, King of Macedon]. So great and wonderful is the influence of a Man, and a mind duly fitted by original constitution for any undertaking within the reach of human powers.” [Source: Polybius, “The Histories of Polybius”, 2 Vols., translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (London: Macmillan, 1889), I.582-586]

The historian Oliver J. Thatcher wrote: “Rome, with the end of the third Punic war, 146 B. C., had completely conquered the last of the civilized world. The best authority for this period of her history is Polybius. He was born in Arcadia, in 204 B. C., and died in 122 B.C. Polybius was an officer of the Achaean League, which sought by federating the Peloponnesus to make it strong enough to keep its independence against the Romans, but Rome was already too strong to be resisted, and arresting a thousand of the most influential members, sent them to Italy to await trial for conspiracy. Polybius had the good fortune, during seventeen years exile, to be allowed to live with the Scipios. He was present at the destructions of Carthage and Corinth, in 146 B. C., and did more than anyone else to get the Greeks to accept the inevitable Roman rule. Polybius is the most reliable, but not the most brilliant, of ancient historians.”

Book: “Pride of Carthage” by David Anthony Durham (Doubleday, 2005), a historical novel about Hannibal

RELATED ARTICLES:

PUNIC WARS AND HANNIBAL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): ROME AND CARTHAGE BATTLE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND SICILY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): CARTHAGE SUCCESSES, ULTIMATE ROMAN VICTORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS: ELEPHANTS, POSSIBLE ROUTES AND HOW HE DID IT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CARTHAGE VICTORIES IN THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF CANNAE: TACTICS, FIGHTING, IMPACT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THIRD PUNIC WAR: ROME DECISIVELY DEFEATS CARTHAGE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hannibal” by Patrick N Hunt (2018) Amazon.com;

“Hannibal: Rome's Greatest Enemy” by Philip Freeman (2023) Amazon.com;

“Pride of Carthage” by David Anthony Durham (Doubleday, 2005), a historical novel about Hannibal Amazon.com;

“Hannibal’s War: A Military History of the Second Punic War” by J. F. Lazenby (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Punic Wars” by Andrian Goldworthy (2001) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Punic Wars” by Dexter Hoyos Amazon.com;

"The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2007) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Carthaginian Wars 265-146 BC” by Terence Wise, Richard Hook (Illustrator) (1982) Amazon.com;

“Carthage: A History” by Serge Lancel (1997) Amazon.com;

“Rome Versus Carthage: The War at Sea” by Christa Steinby (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Roman Republic 264–30 BC: History, Organization and Equipment

by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome From Romulus to Augustus” by Philip Matyszak Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“Carthage Must be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization” by Richard Miles (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

Character of Hannibal

Hannibal

On the character of Hannibal, Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “The Histories”, Book IX, Chapters 22-26: “But since the position of affairs has brought us to inquiry into the genius of Hannibal, the occasion seems to me to demand that I should explain in regard to him the peculiarities of his character which have been especially the subject of controversy. Some regard him as having been extraordinarily cruel, some exceedingly grasping of money. But to speak the truth of him, or of any person engaged in public affairs, is not easy. Some maintain that men's natures are brought out by their circumstances, and that they are detected when in office, or as some say when in misfortunes, though they have up to that time completely maintained their secrecy. 1, on the contrary, do not regard this as a sound dictum. For I think that men in these circumstances are compelled, not occasionally but frequently, either by the suggestions of friends or the complexity of affairs, to speak and act contrary to real principles. [Source: Polybius, “The Histories of Polybius”, 2 Vols., translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (London: Macmillan, 1889), I.582-586]

“And there are many proofs of this to be found in past history if any one will give the necessary attention. Is it not universally stated by the historians that Agathocles, tyrant of Sicily, after having the reputation of extreme cruelty in his original measures for the establishment of his dynasty, when he had once become convinced that his power over the Siceliots was firmly established, is considered to have become the most humane and mild of rulers? Again, was not Cleomenes of Sparta a most excellent king, a most cruel tyrant, and then again as a private individual most obliging and benevolent? And yet it is not reasonable to suppose the most opposite dispositions to exist in the same nature. They are compelled to change with the changes of circumstances: and so some rulers often display to the world a disposition as opposite as possible to their true nature. Therefore, the natures of men not only are not brought out by such things, but on the contrary are rather obscured. The same effect is produced also not only in commanders, despots, and kings, but in states also, by the suggestions of friends. For instance, you will find the Athenians responsible for very few tyrannical acts, and of many kindly and noble ones, while Aristeides and Pericles were at the head of the state: but quite the reverse when Cleon and Chares were so. And when the Lacedaemonians were supreme in Greece, all the measures taken by King Cleombrotus were conceived in the interests of their allies, but those by Agesilaus not so. The characters of states therefore vary with the variations of their leaders. King Philip again, when Taurion and Demetrius were acting with him, was most impious in his conduct, but when Aratus or Chrysogonus, most humane.

“The case of Hannibal seems to me to be on a par with these. His circumstances were so extraordinary and shifting, his closest friends so widely different, that it is exceedingly difficult to estimate his character from his proceedings in Italy. What those circumstances suggested to him may easily be understood from what I have already said, and what is immediately to follow; but it is not right to omit the suggestions made by his friends either, especially as this matter may be rendered sufficiently clear by one instance of the advice offered him. At the time that Hannibal was meditating the march from Iberia to Italy with his army, he was confronted with the extreme difficulty of providing food and securing provisions, both because the journey was thought to be of insuperable length, and because the barbarians that lived in the intervening country were numerous and savage.

Hannibal It appears that at that time the difficulty frequently came on for discussion at the council; and that one of his friends, called Hannibal Monomachus, gave it as his opinion that there was one and only one way by which it was possible to get as far as Italy. Upon Hannibal bidding him speak out, he said that they must teach the army to eat human flesh, and make them accustomed to it. Hannibal could say nothing against the boldness and effectiveness of the idea, but was unable to persuade himself or his friends to entertain it. It is this man's acts in Italy that they say were attributed to Hannibal, to maintain the accusation of cruelty, as well as such as were the result of circumstances.

“Fond of money indeed he does seem to have been to a conspicuous degree, and to have had a friend of the same character — Mago, who commanded in Bruttium. That account I got from the Carthaginians themselves; for natives know best not only which way the wind lies, as the proverb has it, but the characters also of their fellow-countrymen. But I heard a still more detailed story from Massanissa, who maintained the charge of money-loving against all Carthaginians generally, but especially against Hannibal and Mago called the Samnite. Among other stories, he told me that these two men had arranged a most generous subdivision of operations between each other from their earliest youth; and though they had each taken a very large number of cities in Iberia and Italy by force or fraud, they had never taken part in the same operation together; but had always schemed against each other, more than against the enemy, in order to prevent the one being with the other at the taking of a city: that they might neither quarrel in consequence of a thing of this sort nor have to divide the profit on the ground of their equality of rank.

“The influence of friends then, and still more that of circumstances, in doing violence to and changing the natural character of Hannibal, is shown by what I have narrated and will be shown by what I have to narrate. For as soon as Capua fell into the hands of the Romans, the other cities naturally became restless, and began to look round for opportunities and pretexts for revolting back again to Rome. It was then that Hannibal seems to have been at his lowest point of distress and despair. For neither was he able to keep a watch upon all the cities so widely removed from each other — while he remained entrenched at one spot, and the enemy were maneuvering against him with several armies — nor could he divide his force into many parts; for he would have put an easy victory into the hands of the enemy by becoming inferior to them in numbers, and finding it impossible to be personally present at all points. Wherefore he was obliged to completely abandon some of the cities, and withdraw his garrisons from others: being afraid lest, in the course of the revolutions which might occur, he should lose his own soldiers as well. Some cities again he made up his mind to treat with treacherous violence, removing their inhabitants to other cities, and giving their property up to plunder; in consequence of which many were enraged with him, and accused him of impiety or cruelty. For the fact was that these movements were accompanied by robberies of money, murders, and violence, on various pretexts at the hands of the outgoing or incoming soldiers in the cities, because they always supposed that the inhabitants that were left behind were on the verge of turning over to the enemy. It is, therefore, very difficult to express an opinion on the natural character of Hannibal, owing to the influence exercised on it by the counsel of friends and the force of circumstances. The prevailing notion about him, however, at Carthage was that he was greedy of money, at Rome that he was cruel.”

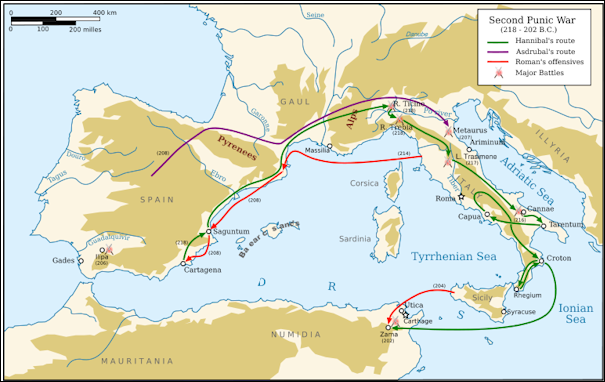

Western Mediterranean at the time of the Second Punic War

Hannibal's Courage and Rome

Bill Mahaney, a professor emeritus at York University in Toronto, told Smithsonian magazine: “Hannibal wasn’t just a brilliant strategist and military tactician. He understood the complexity of human behavior, that command involved more than giving orders and intimidating men to follow him — it involved compromise and shrewd leadership. He impressed the enemy with his courage and daring and swordplay, fighting on the front lines, wading into the thick of battle. He wasn’t some Roman consul sitting behind the troops. During the Italian campaign Hannibal rode an elephant through a swamp off the Arno and lost the sight in his right eye from what was probably ophthalmia. He became a one-eyed general, like Moshe Dayan.” [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2017]

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “Hannibal the Carthaginian, son of Hamilcar. If it be true, as no one doubts, that the Roman people have surpassed all other nations in valor, it must be admitted that Hannibal excelled all other commanders in skill as much as the Roman people are superior to all nations in bravery. For as often as he engaged with that people in Italy, he invariably came off victor; and if his strength had not been impaired by the jealousy of his fellow-citizens at home, he would have been able, to all appearance, to conquer the Romans. But the disparagement of the multitude overcame the courage of one man. Yet after all, he so cherished the hatred of the Romans which had, as it were, been left him as an inheritance by his father, that he would have given up his life rather than renounce it. Indeed, even after he had been driven from his native land and was dependent on the aid of foreigners, he never ceased to war with the Romans in spirit. [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State. Cornelius Nepos is the first surviving biography in Latin.]

“Aside from Philip, whom from afar Hannibal had made an enemy of the Romans, he fired up Antiochus, the most powerful of all kings in those times, with such a desire for war, that from far away on the Red Sea he made preparations to invade Italy. To his court came envoys from Rome to sound his intentions and try by secret intrigues to arouse his suspicions of Hannibal, alleging that they had bribed him and that he had changed his sentiments. These attempts were not made in vain, and when Hannibal learned it and noticed that he was excluded from the king's more intimate councils, he went to Antiochus, as soon as the opportunity offered, and after calling to mind many proofs of his loyalty and his hatred of the Romans, he added, "My father Hamilcar, when I was a small boy not more than nine years old, just as he was setting out from Carthage to Spain as commander-in-chief, offered up victims to Jupiter, Greatest and Best of gods. While this ceremony was being performed, he asked me if I would like to go with him on the campaign. I eagerly accepted and began to beg him not to hesitate to take me with him. Thereupon he said, I will do it, provided you will give me the pledge that I ask. With that he led me to the altar on which he had begun his sacrifice, and having dismissed all the others, he bade me lay hold of the altar and swear that I would never be a friend to the Romans. For my part, up to my present time of life, I have kept the oath which I swore to my father so faithfully, that no one ought to doubt that in the future I shall be of the same mind. Therefore, if you have any kindly intentions with regard to the Roman people, you will be wise to hide them from me; but when you prepare war, you will go counter to your own interests if you do not make me the leader in that enterprise."

Second Punic War

In the Second Punic War, 218-201 B.C., Carthage was anxious to get revenge after the first Punic War. But in the end Rome supplanted Carthage as the predominate power in the Mediterranean. The war was a major milestone in evolution of Rome from a republic into an imperial power.

The Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage were pivotal in making Rome a great empire. The wars began in 264 B.C., and lasted for 118 years with Rome ultimately prevailing. There were three Punic wars. They are regarded as the first world wars. The number of men employed, the strategies and the weapons employed were like nothing that ever been seen before. "Punic" come from the Roman word for "Phoenician, " a reference to Carthage.

The Second Punic War, which occurred 23 years after the First Punic War, was arguable the most important of the Punic Wars. While the First Punic War was primarily an opening round battle primarily over the territory of Sicily, the Second Punic War was viewed as a test of Rome’s power over who would control Europe. At that time Rome and Carthage were struggling for supremacy in the western Mediterranean. The trigger for the conflict was the rapid growth of the Carthaginian dominion in Spain. While Rome was adding to her strength by the conquest of Cisalpine Gaul and the reduction of the islands in the sea, Carthage was building up a great empire in the Spanish peninsula, where it was raising new armies, with which to invade Italy. This policy was launched of the great Carthaginian military commander Hamilcar Barca and was continued by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, who founded the city of New Carthage (Cartagena, Spain) as the capital of the new province. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Second Punic War

Hannibal and the Beginning of the Second Punic War

In 218 B.C., Hannibal left his base in base in Spain and led a force of mercenaries with elephants through the south of Gaul (France) and across the Alps in the winter. This marked the beginning of the Second Punic War. The elephants had little impact on the fight but they scored a psychological blow for the Carthaginians giving them an aura of power and invincibility.

Rome began to be alarmed when Carthage began extending its territory toward the north from southern Spain.. Rome induced Carthage to make a treaty not to extend her conquests beyond the river Iberus (Ebro), in the northern part of Spain. Rome also formed a treaty of alliance with the Greek city of Saguntum, which, though south of the Iberus, was up to this time free and independent. Carthage continued the work of conquering the southern part of Spain, without infringing upon the rights of Rome, until Hasdrubal died. Then Hannibal, the young son of the great Hamilcar, and the idol of the army, was chosen as commander. This young Carthaginian, who had in his boyhood sworn an eternal hostility to Rome, now felt that his mission was come. He marched from New Carthage and proceeded to attack Saguntum, the ally of Rome; and after a siege of eight months, captured it. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Hannibal's father Hasdrubal had (together with his father-in-law Hamilcar) began the conquest of Spain in the south, supposedly with his little boy (Hannibal) at his side. When Hamilcar died in 228 Hasdrubal took over the war effort. When Hasdrubal died in 221, the 21 year old Hannibal took over. The climax of his pushes to the west and north was the successful assault on Saguntum, which occurred while Rome was busy in Illyria. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ]

The Romans sent an embassy to Carthage to demand the surrender of Carthage rejected the Roman embassy demanding Hannibal be given up in reparation for Saguntum, Hannibal. The story is told that Quintus Fabius, the chief Roman envoy, lifted up a fold of his toga and said to the Carthaginian senate, “Here we bring you peace and war; which do you choose?” “Give us either,” was the reply. “Then I offer you war,” said Fabius. “And this we accept,” shouted the Carthaginians. Thus was begun the most memorable war of ancient times.

Rome was now at war, not only with Carthage, but with Hannibal. The first Punic war had been a struggle with the greatest naval power of the Mediterranean, but the second Punic war was to be a conflict with one of the greatest soldiers that the world has ever seen. As a military genius, no Roman could compare with him. If the Romans could have known what ruin and desolation were to follow in the train of this young man of Carthage, they might have hesitated to enter upon this war. But no one could know the future. While Carthage placed her cause in the hands of a brilliant captain, Rome felt that she was supported by a courageous and steadfast people. It will be interesting for us to follow this contest between a great man and a great nation. \~\

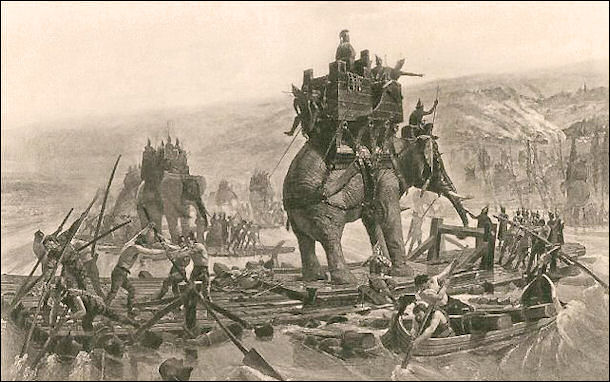

Hannibal crosses the Rhone by Henri Motte 1878

Hannibal Prepares His Army In Spain

When Hannibal was a young man he went with his father to Spain to help rebuild the Carthage army. After the death of his father, Hannibal took over command of the Carthage army. He spent three more years strengthening Carthaginian while the Romans were preparing to attack Carthage.

Hannibal was 25 when he took control of the Carthaginian army in 221 B.C. Within two years he was at odds with Rome after the siege of the Spanish town of Saguntum and showed his military skill early when he attacked the Romans directly not so much to conquer them but to weaken their allies. He began his campaign against Rome in the Second Punic War in 218 B.C. and would remain at war off and on for the next 30 years.

Hannibal donned a toupee before going into battle and commanded an immense army with 50,000 foot soldiers, 9,000 cavalry and 30 now extinct North African elephants. The soldiers were made up primarily of North African, Spanish and Gallic mercenaries recruited from the North African coast and paid for with money from it trading empire.

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “Accordingly, at the age which I have named, Hannibal went with his father to Spain, and after Hamilcar died and Hasdrubal succeeded to the chief command, he was given charge of all the cavalry. When Hasdrubal died in his turn, the army chose Hannibal as its commander, and on their action being reported at Carthage, it was officially confirmed. So it was that when he was less than twenty-five years old, Hannibal became commander-in-chief; and within the next three years he subdued all the peoples of Spain by force of arms, stormed Saguntum, a town allied with Rome, and mustered three great armies. Of these armies he sent one to Africa, left the second with his brother Hasdrubal in Spain, and led the third with him into Italy. He crossed the range of the Pyrenees. Wherever he marched, he warred with all the natives, and he was everywhere victorious.” [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

Before Hannibal crossed the Alps with his elephants, he defeated a group of Iberian tribes in a pivotal 220 B.C. battle fought somewhere along the Tagus River. According to Archaeology magazine: Ancient writers record that Hannibal’s 25,000 soldiers overwhelmed an army of 100,000, but scholars have long argued over exactly where the clash took place. A new study using archaeological, historical, and geomorphological data has finally narrowed down the location to a stretch of river between the towns of Driebes and Illana in the province of Guadalajara. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2020]

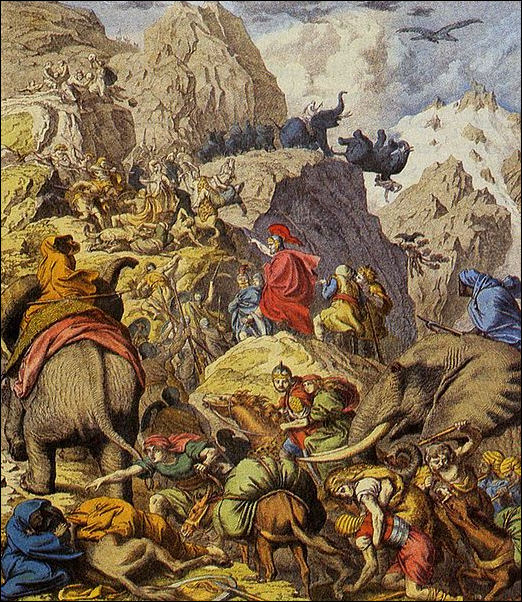

Hannibal crosses the Alps

Hannibal Crosses the Alps

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Initially the Roman strategy was to contain the Carthaginians in northern Spain and southern Gaul from their base at Pisa, while simultaneously campaigning in Africa, where an expeditionary force was to gather local support and block the lines of resupply (probably not, as Polybius believes, to attack Carthage itself). Needless to say, Hannibal had other ideas. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

From his base in Spain Hannibal led a force of mercenaries with elephants through the south of Gaul (France) and across the Alps in the winter of 218 B.C. This marked the beginning of the Second Punic War. The elephants had little impact on the fight but they scored a psychological blow for the Carthaginians giving them an aura of power and invincibility. Hannibal led 50,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry troops and 27 elephants across the Alps. Polybius (3.33 = SB 62) says he saw the exact number (38,000 foot and 8,000 horse) recorded on a bronze tablet set up by Hannibal. In any case, his army crossed the bridge-less Rhone and likely endured snow storms and snow drifts when it crossed the Alps. In some accounts all but one of the elephants and half of Hannibal's soldiers were killed in the Alps.

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “When he came to the Alps separating Italy from Gaul, which no one before him had ever crossed with an army except Hercules (the Greek) because of which that place is called the Greek Pass, he cut to pieces the Alpine tribes that tried to keep him from crossing, opened up the region, built roads, and made it possible for an elephant with its equipment to go over places along which before that a single unarmed man could barely crawl. By this route he led his forces across the Alps and came into Italy.” [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

No one is sure what route Hannibal took. Much of what has been written about the elephants and Alps is speculation. On the subject of Hannibal's route, Mark Twain once wrote: "The researches of many antiquarians have already thrown much darkness on the subject, and it is probable, if they continue, that we shall soon know nothing at all." Much of the imagery of Hannibal and his elephants comes from Flaubert's Salammbo .

Most scholars believe that after crossing the Alps, Hannibal’s army arrived in Italy near the source of the Po River at Col de la Traversette and caught Roman armies by surprise even though Hannibal's attack was forecast by the sacred of chickens of Claudius Pulcher. The Roman general Marcellus rode with blinds on his litter pulled down so he wouldn't send any bad omen.

See Separate Article: HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS WITH HIS ELEPHANTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Hannibal’s Invades Italy and Defeats the Romans

Hannibal's invasion route

Hannibal finally reached the valley of the Po, with only twenty thousand foot and six thousand horse. Here he recruited his ranks from the Gauls, who eagerly joined his cause against the Romans. When the Romans were aware that Hannibal was really in Italy, they made preparations to meet and to destroy him. Sempronius was recalled with the army originally intended for Africa; and Scipio, who had returned from Massilia, gathered together the scattered forces in northern Italy and took up his station at Placentia on the Po. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Hannibal won three battles in Italy but lost the forth. Early Carthaginian victories left 15,000 Romans dead in one place and 20,000 in another. With their superior cavalry and what became textbook usage of bottlenecking tactics, Hannibal's forces defeated the Roman force of Flamininius in 217 B.C. at Lake Trasimene. Next he humiliated the Romans, by coldly coordinating his infantry and cavalry attacks, at Cannae in northern Italy, where 60,000 Romans were killed. This victory drew the north of Italy from Rome's sphere for some time.

These victories were followed by a massacre of 50,000 legionnaires (from an army of 75,000) at the Trebia River. Here the Roman were surrounded by flanking movements on both sides. Hannibal's genius killed 6000 legionnaires in minutes. After the stunning defeats, one Roman army was annihilated and Rome was nearly destroyed. The Romans were worried that Hannibal would take his revenge in most awful way. The statesmen Quintus Fabius Maximus was put in charge of the Roman army.

Hannibal’s Defeat and End of the Second Punic War (201 B.C.)

Hannibal spent a total of 15 years in Italy and although he was able to defeat the Romans in key battles he was ultimately defeated because the Romans had a large population to draw new recruits from and Carthage's mercenary forces shrank as time went on. The Roman armies under Fabius followed the Carthaginians and wore them down with delaying and harassing tactics. During the Battle of the Metaurus, Hannibal and his brother were defeated at the Metaurus River by 7,000 Romans in 207 B.C.

According to a peace treaty of 201 B.C. that ended the second Punic War, Carthage had to promise forever to refrain from capturing and training North African elephants. The entire Carthaginian fleet was towed out to see and burned and Carthaginian aristocrats were forced pay reparations out of their own pockets. After the Second Punic War, Carthage turned its attention to trading and became rich and prosperous once again.

The terms imposed by Scipio the terms of peace included: 1) Carthage was to give up the whole of Spain and all the islands between Africa and Italy; 2) Masinissa was recognized as the king of Numidia and the ally of Rome; (3) Carthage was to pay an annual tribute of 200 talents for fifty years; (4) Carthage agreed not to wage any war without the consent of Rome. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Hannibal Returns to Carthage

Hannibal While the war was progressing in Africa, Hannibal still held his place in Bruttium like a lion at bay, or maybe a rat in a corner. In the midst of misfortune, he was still a hero. He kept control of his devoted army, and was faithful to his duty when all was lost. Carthage was convinced that her only hope was in recalling Hannibal to defend his native city. Hannibal left Italy in 203 B.C., the field of his brilliant exploits, and landed in Africa. Thus Rome was relieved of her dreaded foe, who had brought her so near to the brink of ruin. \~\

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “Then, undefeated, he was recalled to defend his native land; there he carried on war against Publius Scipio, the son of that Scipio whom he had put to flight first at the Rhone, then at the Po, and a third time at the Trebia. With him, since the resources of his country were now exhausted, he wished to arrange a truce for a time, in order to carry on the war later with renewed strength. He had an interview with Scipio, but they could not agree upon terms. A few days after the conference he fought with Scipio at Zama. Defeated incredible to relate he succeeded in a day and two nights in reaching Hadrumetum, distant from Zama about three hundred miles. In the course of that retreat the Numidians who had left the field with him laid a trap for him, but he not only eluded them, but even crushed the plotters. At Hadrumetum he rallied the survivors of the retreat and by means of new levies mustered a large number of soldiers within a few days. [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

“While he was busily engaged in these preparations, the Carthaginians made peace with the Romans. Hannibal, however, continued after that to command the army and carried on war in Africa until the consulship of Publius Sulpicius and Gaius

Rome thus became the main power of the western Mediterranean. Carthage, although not reduced to a province, became a dependent state. Syracuse was added to the province of Sicily, and the territory of Spain was divided into two provinces, Hither and Farther Spain. Rome had, moreover, been brought into hostile relations with Macedonia, which paved the way for her conquests in the East. \~\

Hannibal Flees Carthage

In the midst of all this, Hannibal fled Carthage. To the Romans it seemed an act of treachery that Hannibal, who had been conquered in a fair field at Zama, should continue his hostility by fighting on the side of their enemies. But Hannibal never forgot the oath of eternal enmity to Rome, the oath which he had sworn at his father’s knee. When Antiochus agreed to surrender him, Hannibal fled to Crete, and afterward took refuge with the king of Bithynia.

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “Then in the following year, when Marcus Claudius and Lucius Furius were consuls, envoys came to Carthage from Rome. Hannibal thought that they had been sent to demand his surrender; therefore, before they were given audience by the senate, he secretly embarked on a ship and took refuge with King Antiochus in Syria. When this became known, the Carthaginians sent two ships to arrest Hannibal, if they could overtake him; then they confiscated his property, demolished his house from its foundations, and declared him an outlaw. [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

“But Hannibal, in the third year after he had fled from his country, in the consulship of Lucius Cornelius and Quintus Minucius, with five ships landed in Africa in the territories of Cyrene, to see whether the Carthaginians could by any chance be induced to make war by the hope of aid from King Antiochus, whom Hannibal had already persuaded to march upon Italy with his armies. To Italy also he dispatched his brother Mago. When the Carthaginians learned this, they inflicted on Mago in his absence the same penalty that Hannibal had suffered. The brothers, regarding the situation as desperate, raised anchor and set sail. Hannibal reached Antiochus; as to the death of Mago there are two accounts; some have written that he was shipwrecked; others, that he was killed by his own slaves. As for Antiochus, if he had been as willing to follow Hannibal's advice in the conduct of the war as he had been in declaring it, he would not have fought for the rule of the world at Thermopylae, but nearer to the Tiber. But although Hannibal saw that many of the king's plans were unwise, yet he never deserted him. On one occasion he commanded a few ships, which he had been ordered to take from Syria to Asia, and with them he fought against a fleet of the Rhodians in the Pamphylian Sea. Although in that engagement his forces were defeated by the superior numbers of their opponents, he was victorious on the wing where he fought in person.

Battle of Zama fighting

“After Antiochus had been defeated, Hannibal, fearing that he would be surrendered to the Romans — as undoubtedly would have happened, if he had let himself be taken — came to the Gortynians in Crete, there to deliberate where to seek asylum. But being the shrewdest of all men, he realized that he would be in great danger, unless he devised some means of escaping the avarice of the Cretans; for he was carrying with him a large sum of money, and he knew that news of this had leaked out. He therefore devised the following plan: he filled a number of large jars with lead and covered their tops with gold and silver. These, in the presence of the leading citizens, he deposited in the temple of Diana, pretending that he was entrusting his property to their protection. Having thus misled them, he filled some bronze statues which he was carrying with him with all his money and threw them carelessly down in the courtyard of his house. The Gortynians guarded the temple with great care, not so much against others as against Hannibal, to prevent him from taking anything without their knowledge and carrying it off with him.

“Thus he saved his goods, and having tricked all the Cretans, the Carthaginian joined Prusias in Pontus. At his court he was of the same mind towards Italy and gave his entire attention to arming the king and training his forces to meet the Romans. And seeing that Prusias' personal resources did not give him great strength, he won him the friendship of the other kings of that region and allied him with warlike nations. Prusias had quarreled with Eumenes, king of Pergamum, a strong friend of the Romans, and they were fighting with each other by land and sea. But Eumenes was everywhere the stronger because of his alliance with the Romans, and for that reason Hannibal was the more eager for his overthrow, thinking that if he got rid of him, all his difficulties would be ended.

Hannibal Continues His Fight Against Rome

Hannibal received asylum in Bithnynia (in what is now Turkey). There he continued his fight against Rome by aiding this ruler in a war against Rome’s ally, the king of Pergamum. The Romans still pursued him, and sent Flamininus to demand his surrender.Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “To cause his death, he formed the following plan. Within a few days they were intending to fight a decisive naval battle. Hannibal was outnumbered in ships; therefore it was necessary to resort to a ruse, since he was unequal to his opponent in arms. He gave orders to collect the greatest possible number of venomous snakes and put them alive in earthenware jars. When he had got together a great number of these, on the very day when the sea-fight was going to take place he called the marines together and bade them concentrate their attack on the ship of Eumenes and be satisfied with merely defending themselves against the rest; this they could easily do, thanks to the great number of snakes. Furthermore, he promised to let them know in what ship Eumenes was sailing, and to give them a generous reward if they succeeded in either capturing or killing the king. [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

Hannibal “After he had encouraged the soldiers in this way, the fleets on both sides were brought out for battle. When they were drawn up in line, before the signal for action was given, in order that Hannibal might make it clear to his men where Eumenes was, he sent a messenger in a skiff with a herald's staff. When the emissary came to the ships of the enemy, he exhibited a letter and said that he was looking for the king. He was at once taken to Eumenes since no one doubted that it was some communication about peace. The letter-carrier, having pointed out the commander's ship to his men, returned to the place from which he came. But Eumenes, on opening the missive, found nothing in it except what was designed to mock at him. Although he wondered at the reason for such conduct and could not find one, he nevertheless did not hesitate to join battle at once.

“When the clash came, the Bithynians did as Hannibal had ordered and fell upon the ship of Eumenes in a body. Since the king could not resist their force, he sought safety in flight, which he secured only by retreating within the entrenchments which had been thrown up on the neighboring shore. When the other Pergamene ships began to press their opponents too hard, on a sudden the earthenware jars of which I have spoken began to be hurled at them. At first these projectiles excited the laughter of the combatants, and they could not understand what it meant. But as soon as they saw their ships filled with snakes, terrified by the strange weapons and not knowing how to avoid them, they turned their ships about and retreated to their naval camp. Thus Hannibal overcame the arms of Pergamum by strategy; and that was not the only instance of the kind, but on many other occasions in land battles he defeated his antagonists by a similar bit of cleverness.”

Capture and Death of Hannibal

Hannibal’s time ran out in 182 B.C. when the potentate of Bithynia gave him up. To avoid capture by the Romans, Hannibal committed suicide while in exile near present-day Istanbul by drinking poison. According to some sources he died the same year (183 B.C.) as his great foe Scipio Africanus.

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “While this was taking place in Asia, it chanced that in Rome envoys of Prusias were dining with Titus Quinctius Flamininus, the ex-consul, and that mention being made of Hannibal, one of the envoys said that he was in the kingdom of Prusias. On the following day Flamininus informed the senate. The Fathers, believing that while Hannibal lived they would never be free from plots. sent envoys to Bithynia, among them Flamininus, to request the king not to keep their bitterest foe at his court, but to surrender him to the Romans. Prusias did not dare to refuse; he did, however, stipulate that they would not ask him to do anything which was in violation of the laws of hospitality. They themselves, if they could, might take him; they would easily find his place of abode. As a matter of fact, Hannibal kept himself in one place, in a stronghold which the king had given him, and he had so arranged it that he had exits in every part of the building, evidently being in fear of experiencing what actually happened. [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

Hannibal's death

“When the envoys of the Romans had come to the place and surrounded his house with a great body of troops, a slave looking out from one of the doors reported that an unusual number of armed men were in sight. Hannibal ordered him to go about to all the doors of the building and hasten to inform him whether he was beset in the same way on every side. The slave having quickly reported the facts and told him that all the exits were guarded, Hannibal knew that it was no accident; that it was he whom they were after and he must no longer think of preserving his life. But not wishing to lose it at another's will, and remembering his past deeds of valor, he took the poison which he always carried about his person.

“Thus that bravest of men, after having performed many and varied labors, entered into rest in his seventieth year. Under what consuls he died is disputed. For Atticus has recorded in his Annals that he died in the consulate of Marcus Claudius Marcellus and Quintus Fabius Labeo; Polybius, under Lucius Aemilius Paulus and Gnaeus Baebius Tamphilus; and Sulpicius Blitho, in the time of Publius Cornelius Cethegus and Marcus Baebius Tamphilus. And that great man, although busied with such great wars, devoted some time to letters; for there are several books of his, written in Greek, among them one, addressed to the Rhodians, on the deeds of Gnaeus Manlius Volso in Asia. Hannibal's deeds of arms have been recorded by many writers, among them two men who were with him in camp and lived with him so long as fortune allowed, Silenus and Sosylus of Lacedaemon. And it was this Sosylus whom Hannibal employed as his teacher of Greek.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024