Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.)

HANNIBAL

Hannibal Hannibal (247-183 B.C.) was a cagey strategist who came close to destroying Rome through his military skill and cheeky audacity. He played a pivotal role in one the greatest what-if moments in world history. Napoleon regarded Hannibal as the greatest military man of antiquity. Not only did he outmaneuver the great Roman legions, he managed the logistics of getting his army through the Alps to surprise Rome. Hannibal came within a whisker of defeating Rome. If he had won the world might have had a more difficult time spelling a Carthaginian Empire than a Roman one.

Hannibal was the son of Hamilcar Barca. Hamilcar Barca rebuilt Carthage after the first Punic War. Lacking the means to rebuild the Carthaginian fleet he built an army in Spain. Before taking power, Hannibal was reportedly required by his father to forever be an enemy of Rome. Reportedly he stood before an altar and swore: “I will follow the Romans both at sea and on land. I will use fire and metal to arrest the destiny of Rome.

Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “The Histories”: “Of all that befell the Romans and Carthaginians, good or bad, the cause was one man and one mind — Hannibal. For it is notorious that he managed the Italian campaigns in person, and the Spanish by the agency of the elder of his brothers, Hasdrubal, and subsequently by that of Mago, the leaders who killed the two Roman generals in Spain about the same time. Again, he conducted the Sicilian campaign first through Hippocrates and afterwards through Myttonus the Libyan. So also in Greece and Illyria: and, by brandishing before their faces the dangers arising from these latter places, he was enabled to distract the attention of the Romans thanks to his understanding with King Philip [Philip V, King of Macedon]. So great and wonderful is the influence of a Man, and a mind duly fitted by original constitution for any undertaking within the reach of human powers.” [Source: Polybius, “The Histories of Polybius”, 2 Vols., translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (London: Macmillan, 1889), I.582-586]

RELATED ARTICLES:

HANNIBAL: HIS LIFE, ACHIEVEMENTS AGAINST ROME, EXILE, DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PUNIC WARS AND HANNIBAL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): ROME AND CARTHAGE BATTLE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND SICILY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THIRD PUNIC WAR: ROME DECISIVELY DEFEATS CARTHAGE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hannibal: Rome's Greatest Enemy” by Philip Freeman (2023) Amazon.com;

“Hannibal's Road: The Second Punic War in Italy, 213–203 BC”

by Mike Roberts (2020) Amazon.com;

“Hannibal” by Patrick N Hunt (2018) Amazon.com;

“Pride of Carthage” by David Anthony Durham (Doubleday, 2005), a historical novel about Hannibal Amazon.com;

“Hannibal’s War: A Military History of the Second Punic War” by J. F. Lazenby (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Punic Wars” by Andrian Goldworthy (2001) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Punic Wars” by Dexter Hoyos Amazon.com;

"The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2007) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Carthaginian Wars 265-146 BC” by Terence Wise, Richard Hook (Illustrator) (1982) Amazon.com;

“Carthage: A History” by Serge Lancel (1997) Amazon.com;

“Rome Versus Carthage: The War at Sea” by Christa Steinby (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Roman Republic 264–30 BC: History, Organization and Equipment

by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome From Romulus to Augustus” by Philip Matyszak Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“Carthage Must be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization” by Richard Miles (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.)

Hannibal The Second Punic War, which occurred 23 years after the First Punic War, was arguable the most important of the Punic Wars. While the First Punic War was primarily an opening round battle primarily over the territory of Sicily, the Second Punic War was viewed as a test of Rome’s power over who would control Europe. At that time Rome and Carthage were struggling for supremacy in the western Mediterranean. The trigger for the conflict was the rapid growth of the Carthaginian dominion in Spain. While Rome was adding to her strength by the conquest of Cisalpine Gaul and the reduction of the islands in the sea, Carthage was building up a great empire in the Spanish peninsula, where it was raising new armies, with which to invade Italy. This policy was launched of the great Carthaginian military commander Hamilcar Barca and was continued by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, who founded the city of New Carthage (Cartagena, Spain) as the capital of the new province. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

In 218 B.C., Hannibal left his base in base in Spain and led a force of mercenaries with elephants through the south of Gaul (France) and across the Alps in the winter. This marked the beginning of the Second Punic War. The elephants had little impact on the fight but they scored a psychological blow for the Carthaginians giving them an aura of power and invincibility.

In the Second Punic War, 218-201 B.C., Carthage was anxious to get revenge after the first Punic War. But in the end Rome supplanted Carthage as the predominate power in the Mediterranean. The war was a major milestone in evolution of Rome from a republic into an imperial power.

See Separate Articles: SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ; HANNIBAL europe.factsanddetails.com ; CANNAE AND KEY BATTLES OF THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com

Hannibal Crosses the Alps

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Initially the Roman strategy was to contain the Carthaginians in northern Spain and southern Gaul from their base at Pisa, while simultaneously campaigning in Africa, where an expeditionary force was to gather local support and block the lines of resupply (probably not, as Polybius believes, to attack Carthage itself). Needless to say, Hannibal had other ideas. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

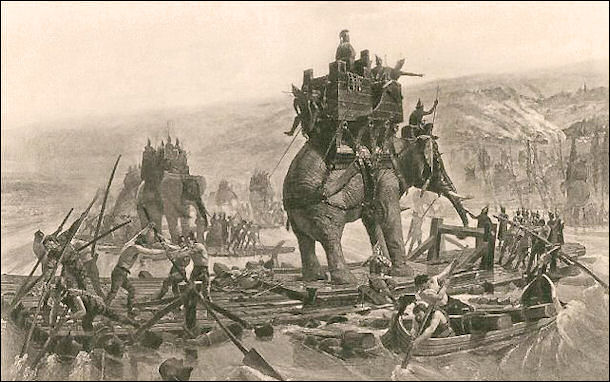

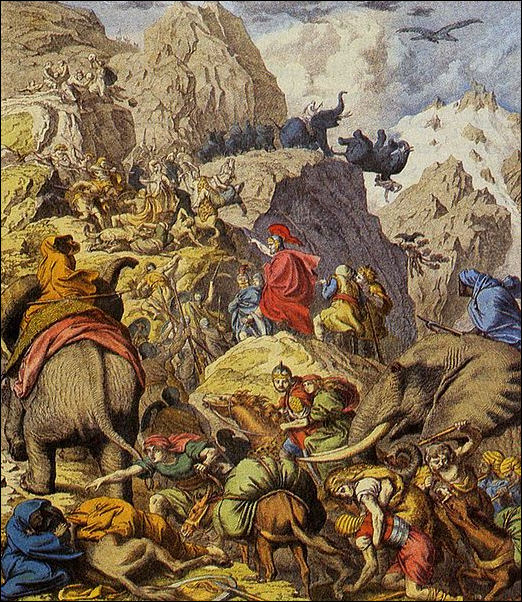

From his base in Spain Hannibal led a force of mercenaries with elephants through the south of Gaul (France) and across the Alps in the winter of 218 B.C. This marked the beginning of the Second Punic War. The elephants had little impact on the fight but they scored a psychological blow for the Carthaginians giving them an aura of power and invincibility. Hannibal led 50,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry troops and 27 elephants across the Alps. Polybius (3.33 = SB 62) says he saw the exact number (38,000 foot and 8,000 horse) recorded on a bronze tablet set up by Hannibal. In any case, his army crossed the bridge-less Rhone and likely endured snow storms and snow drifts when it crossed the Alps. In some accounts all but one of the elephants and half of Hannibal's soldiers were killed in the Alps.

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “When he came to the Alps separating Italy from Gaul, which no one before him had ever crossed with an army except Hercules (the Greek) because of which that place is called the Greek Pass, he cut to pieces the Alpine tribes that tried to keep him from crossing, opened up the region, built roads, and made it possible for an elephant with its equipment to go over places along which before that a single unarmed man could barely crawl. By this route he led his forces across the Alps and came into Italy.” [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

No one is sure what route Hannibal took. Much of what has been written about the elephants and Alps is speculation. On the subject of Hannibal's route, Mark Twain once wrote: "The researches of many antiquarians have already thrown much darkness on the subject, and it is probable, if they continue, that we shall soon know nothing at all." Much of the imagery of Hannibal and his elephants comes from Flaubert's Salammbo .

Most scholars believe that after crossing the Alps, Hannibal’s army arrived in Italy near the source of the Po River at Col de la Traversette and caught Roman armies by surprise even though Hannibal's attack was forecast by the sacred of chickens of Claudius Pulcher. The Roman general Marcellus rode with blinds on his litter pulled down so he wouldn't send any bad omen.

Why Hannibal Crossed the Alps

Hannibal crossed to Alps in a bid to outflank and surprise the Romans in their own territory. The Romans had sent two armies into Carthaginian territory—one into Africa under Sempronius, and the other into Spain under P. Cornelius Scipio (sip'i-o). But Hannibal, with the instinct of a true soldier, saw that Carthage would be safe if Italy were invaded and Rome threatened. Leaving his brother Hasdrubal to protect Spain, he crossed the Pyrenees pushed on to the river Rhone, outflanking the Gauls there, who were trying to oppose his passage; and crossed the river above, just as the Roman army (which had expected to meet him in Spain) had reached Massilia (Marseilles). When the Roman commander, P. Cornelius Scipio, found that he had been outgeneraled by Hannibal, he sent his brother Cn. Scipio on to Spain with the main army, and returned himself to Cisalpine Gaul, expecting to destroy the Carthaginian if he should venture to come into Italy. Hannibal in the meantime pressed on; and in spite of innumerable difficulties and dangers crossed the Alps. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “In ancient warfare surprise was sometimes possible at the tactical level, almost never at the strategic level. A Roman force (under P. Cornelius Scipio) set out to prevent Hannibal's crossing of the Rhone, but was distracted by a Gallic uprising, so that by the time it got to the river Hannibal and his army had already crossed. Rather than chase Hannibal, Scipio chose to send his troops on to meet up with his brother Gn. Scipio's forces in Spain; but it was not long before P. Scipio himself was recalled to Italy to deal with the immediate threat. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Hannibal crossed the Alps in 218 B.C. (there is a debate of long standing over what precisely was his route). The crossing was extremely hard both on his army and his animals; when it was completed, not much more than half of the original army remained (Polyb. 3. 60). But the losses were partly made good by the addition of several Gallic tribes, including one contingent of some 2,000 men which was actually under arms in the Roman camp before turning on the Romans and defecting to Hannibal's side.” ^*^

Hannibal Prepares His Army In Spain

When Hannibal was a young man he went with his father to Spain to help rebuild the Carthage army. After the death of his father, Hannibal took over command of the Carthage army. He spent three more years strengthening Carthaginian while the Romans were preparing to attack Carthage.

Hannibal was 25 when he took control of the Carthaginian army in 221 B.C. Within two years he was at odds with Rome after the siege of the Spanish town of Saguntum and showed his military skill early when he attacked the Romans directly not so much to conquer them but to weaken their allies. He began his campaign against Rome in the Second Punic War in 218 B.C. and would remain at war off and on for the next 30 years.

Hannibal donned a toupee before going into battle and commanded an immense army with 50,000 foot soldiers, 9,000 cavalry and 30 now extinct North African elephants. The soldiers were made up primarily of North African, Spanish and Gallic mercenaries recruited from the North African coast and paid for with money from it trading empire.

Hannibal crosses the Rhone by Henri Motte 1878

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “Accordingly, at the age which I have named, Hannibal went with his father to Spain, and after Hamilcar died and Hasdrubal succeeded to the chief command, he was given charge of all the cavalry. When Hasdrubal died in his turn, the army chose Hannibal as its commander, and on their action being reported at Carthage, it was officially confirmed. So it was that when he was less than twenty-five years old, Hannibal became commander-in-chief; and within the next three years he subdued all the peoples of Spain by force of arms, stormed Saguntum, a town allied with Rome, and mustered three great armies. Of these armies he sent one to Africa, left the second with his brother Hasdrubal in Spain, and led the third with him into Italy. He crossed the range of the Pyrenees. Wherever he marched, he warred with all the natives, and he was everywhere victorious.” [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

Before Hannibal crossed the Alps with his elephants, he defeated a group of Iberian tribes in a pivotal 220 B.C. battle fought somewhere along the Tagus River. According to Archaeology magazine: Ancient writers record that Hannibal’s 25,000 soldiers overwhelmed an army of 100,000, but scholars have long argued over exactly where the clash took place. A new study using archaeological, historical, and geomorphological data has finally narrowed down the location to a stretch of river between the towns of Driebes and Illana in the province of Guadalajara. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2020]

Hannibal Heads Into the Alps

The first view of the Alps by Hannibal’s soldiers must have been a sobering one . “The dreadful vision was now before their eyes,” wrote Livy. As he led his troops into the mountains, Hannibal vowed: “You will have the capital of Italy, the citadel of Rome, in the hollow of your hands.”

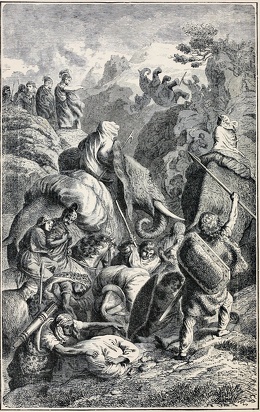

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Accustomed to the warmth of Africa and New Carthage, the liquid legions flowed through Spain, France and the trackless, snowbound Alps, holding at bay the Allobroges, a mountain tribe that set ambushes, slung arrows and rained great rocks upon their heads. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2017]

In “Histories” Polybius’ wrote: “Hannibal could see that the hardship they had experienced, and the anticipation of more to come, had sapped morale throughout the army. He convened an assembly and tried to raise their spirits, though his only asset was the visibility of Italy, which spreads out under the mountains in such a way that, from a panoramic perspective, the Alps form the acropolis of all Italy.”

Bill Mahaney, a professor emeritus at York University in Toronto, told Smithsonian magazine: “It’s a wonder Hannibal didn’t get a spear in his back. By the time he delivered his speech at the top of the pass, many of his mercenaries were either dead, starving to death or suffering from hypothermia. Yet Hannibal didn’t lose a single elephant.”

Hannibal crosses the Alps

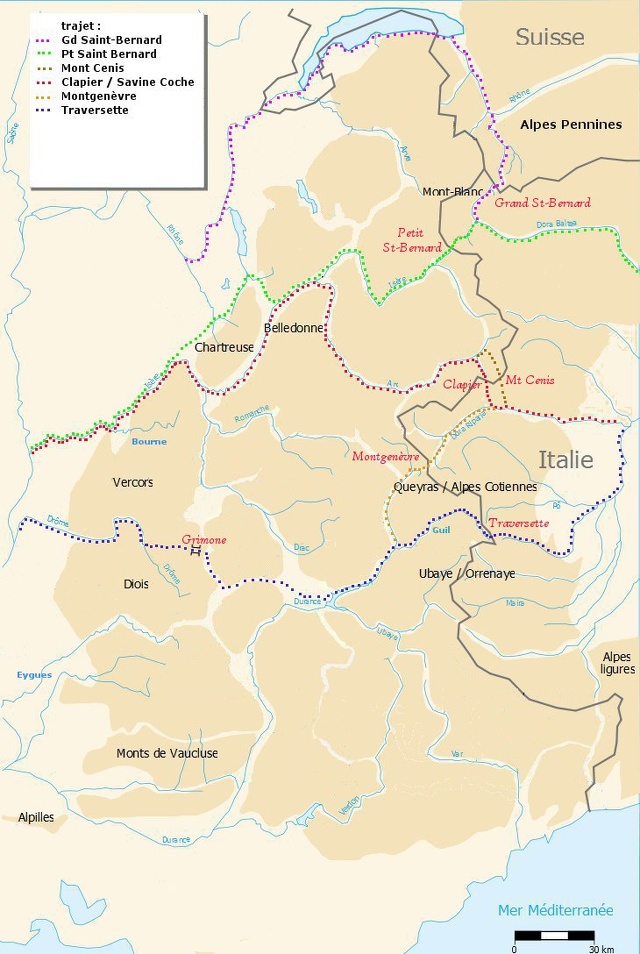

What Route Did Hannibal Take to Cross the Alps

What route did Hannibal take to cross the Alps. Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The vexed question is one of those problems on the borderline of history and geography that are fascinating and perhaps insoluble. Much ink has been spilled in pinpointing the route of Hannibal’s improbable five-month, thousand-mile trek from Catalonia across the Pyrenees, through the Languedoc to the banks of the Rhone, and then over the Alps to the plains of Italy. Many boots have been worn out in determining the alpine pass through which tens of thousands of foot soldiers and cavalrymen, thousands of horses and mules, and, famously, 37 African battle elephants tramped. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2017]

“Speculation on the crossing place stretches back more than two millennia to when Rome and Carthage, a North African city-state in what is now Tunisia, were superpowers vying for supremacy in the Mediterranean. No Carthaginian sources of any kind have survived, and the accounts by the Greek historian Polybius (written about 70 years after the March) and his Roman counterpart Livy (120 years after that) are maddeningly vague.

There are no fewer than a dozen rival theories advanced by a rich confusion of academics, antiquarians and statesmen who contradict one another and sometimes themselves. Napoleon Bonaparte favored a northern route through the Col du Mont Cenis. Edward Gibbon, author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, was said to be a fan of the Col du Montgenèvre. Sir Gavin de Beer, a onetime director of what is now the Natural History Museum in London, championed the Traversette, the gnarliest and most southerly course. In 1959, Cambridge engineering student John Hoyte borrowed an elephant named Jumbo from the Turin zoo and set out to prove the Col du Clapier (sometimes called the Col du Clapier-Savine Coche) was the real trunk road — but ultimately took the Mont Cenis route into Italy. Others have charted itineraries over the Col du Petit St. Bernard, the Col du l’Argentière and combinations of the above that looped north to south to north again. To borrow a line attributed to Mark Twain, riffing on a different controversy: “The researches of many commentators have already thrown much darkness on this subject, and it is probable that, if they continue, we shall soon know nothing at all about it.”

“Curiously, there’s no record of Punic armaments of any kind having been recovered from the various passes. Nor have archaeologists found evidence of Punic burials or Carthaginian coins. Mahaney is seeking financial backing to conduct further research at the Traversette mire, a site, he says, that might benefit from the use of ground-penetrating radar. “But first we’d need permits from the French government. And the French, for all intents and purposes, invented ruban rouge,” Mahaney says, using the French term for red tape.

Which Pass Did Hannibal Take to Cross The Alps

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Exactly which pass Hannibal used has been a source of endless dust-ups among Hannibalologists. One thing they all seem to agree on is a set of environmental parameters that any prospective pass must fit: 1) A day’s March from a narrow gorge, where Hannibal’s men walked single file and tribesmen hidden on cliffs began their assault. 2) A “white” or “bare” rock place, where some of his fleeing troops spent that night. 3) A clearing on the approach near the summit, surrounded by year-round snow, large enough to camp an army of at least 25,000. And a point on the summit where the troops could gaze down to the Po River Plain. 4) A steep, slippery descent on the Italian side that’s hemmed in by precipices and bottoms out in a valley suitable for pasturing horses and pack animals. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2017]

“Mahaney contends that the Traversette is the only pass that fulfills these criteria. Then again, Patrick Hunt — a historian and archaeologist at Stanford, former director of the university’s Alpine Archaeology Project and author of the new biography Hannibal — makes the same claim for the Col du Clapier. They’ve both studied soil chemistry and postglacial weathering of moraines along the passes. Both have scanned satellite images, scrutinized lichen growth and rock weathering rates, and modeled historical glaciation to help envision how the land today may have changed since Hellenistic times. And both think the other’s inferences are a lot of Hannibaloney.

“In 2004 Mahaney discovered a two-tiered rockfall — caused by two separate accumulations of rubble — on the Traversette’s Italian frontier. The fallen mass, he says, jibes with Polybius’ description of the rock debris that impeded the elephant brigade’s path to the valley. “None of the other passes have a deposit on the lee side,” he insists.

“Hunt counters that the Col du Clapier also has multilayered rockfalls, having buried much of the later Roman and earlier Celtic terraced roadbed under multiple layers of talus. He adds that “rockfall” is a mistranslation of the Greek word for landslip, and that Polybius was actually referring to a slender track along a mountainside interrupted by a drop where the slope had fallen away. “Polybius states Hannibal’s forces slipped through fresh snow to ice below from the previous winter on the initial descent,” he says. “Mahaney tries to get around the lack of snow traces on the Traversette by reading snow and ice as firn, or frozen ground. This is not philology, this is creative wishful thinking.”

“Hunt thinks the Traversette’s descent would be narrow for elephants; Mahaney, who observed the beasts traversing Mount Kenya when he climbed there, thinks they’d have had no problem taking the high road. And while Hunt thinks the Traversette would have been too high and the terrain too treacherous for humans, Mahaney thinks the Col du Clapier would have been too low and the terrain not treacherous enough: “An army of nuns could walk straight down off the Clapier into Italy,” he says, snickering like a schoolboy who’s just discovered there’s a city in France named Brest. “Hunt implies that the Traversette may not have been passable in Hannibal’s time, but I don’t think he has a grasp of what Hannibal’s warriors actually looked like. You wouldn’t want to meet them on a dark night, anywhere. They were crack troops who could cover 20 miles a day while lugging food and weapons.”

Researchers Who Studied the Possible Routes Used by Hannibal

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The earliest scholar to argue for the Traversette. was a naturalist named Cecil Torr, who in his 1924 book Hannibal Crosses the Alps tells us that as a teenager he set out, fruitlessly, to find traces of vinegar used, after fires were set to heat rock, in fracturing boulders that blocked the Carthaginian army. (A procedure, notes Cambridge classical scholar Mary Beard, “which has launched all kinds of boy-scoutish experiments among classicists-turned-amateur-chemists.”) Still, Torr was branded a Hannibal heretic and the route he recommended was dismissed as untenable. His theory was largely ignored until 1955, when Gavin de Beer took up the cause. In Alps and Elephants, the first of several books that the evolutionary embryologist wrote on Hannibal, he displayed something of the Kon-Tiki spirit with the claim that he’d personally inspected the topography. For centuries only traders and smugglers had used the Traversette; scholars avoided it not just because the climb was so dicey, but due to what de Beer called “the ease with which triggers are pulled in that area.” [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2017]

“De Beer gave the topic the scrubbing it deserved, consulting philologists, invoking astronomy to date the setting of the Pleiades, identifying river crossings by plotting seasonal flow, analyzing pollen to estimate the climate in 218 B.C., and combing through historical literature to tie them to geographical evidence. All who have played the Hannibal game know they must discover in their chosen pass a number of specific features that correlate with the chronicles of Polybius and Livy. One by one, de Beer demolished the wealth of alternatives. “Of course,” he added disarmingly, “I may be wrong.”

“F.W. Walbank certainly thought so. The eminent Polybian scholar refuted de Beer’s conclusions on linguistic and timeline grounds in “Some Reflections on Hannibal’s Pass,” published in Volume 46 of The Journal of Roman Studies. His 1956 essay began with the all-time Carthaginian money quote: “Few historical problems have produced more unprofitable discussion than that of Hannibal’s pass over the Alps.” Walbank, who seemed inclined toward either Col du Clapier or Mont Cenis, was later dressed down by Geoffroy de Galbert, author of Hannibal and Caesar in the Alps, for allegedly misreading Polybius’ Greek. (If you’re keeping score, de Galbert is a Col du Clapier man.)

Mahaney is an outspoken exponent of the Traversette. He spent assessing possible Punic routes by surveying every pass on the French-Italian border. His quest has yielded two books: Hannibal’s Odyssey: The Environmental Background to the Alpine Invasion of Italia and The Warmaker, a novel whose lusty dialogue could have been airlifted from the 1960 film Hannibal, a Victor Mature blockbuster taglined “What My Elephants Can’t Conquer, I Will Conquer Alone!”

Does Ancient Poop in the Alps Offer Evidence That Hannibal Took the Traversette Route?

Chris Allen, a lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast, contends he has found what could quite possibly be 2,000- year-old elephant poop in the Alps along the Traversette Route — thus providing pretty good evidence that — thus proving that Hannibal took that route. Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: ““Embedded 16 inches deep in a bog on the French side of the Traversette is a thin layer of churned-up, compacted scat that suggests a large footfall by thousands of mammals at some point in the past. “If Hannibal had hauled his traveling circus over the pass, he would have stopped at the mire to water and feed the beasts,” reasons Allen. “And if that many horses, mules and, for that matter, elephants did graze there, they would have left behind a MAD.” That’s the acronym for what microbiologists delicately term a “mass animal deposition.” [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2017]

By examining sediment from two cores and a trench — mostly soil matted with decomposed plant fiber — Allen and his crew have identified genetic materials that contain high concentrations of DNA fragments from Clostridia, bacteria that typically make up only 2 or 3 percent of peat microbes, but more than 70 percent of those found in the gut of horses. The bed of excrement also contained unusual levels of bile acids and fatty compounds found in the digestive tracts of horses and ruminants. Allen is most excited about having isolated parasite eggs — associated with gut tapeworms — preserved in the site like tiny genetic time capsules. “The DNA detected in the mire was protected in bacterial endospores that can survive in soil for thousands of years,” he says. Analyses by the team, including carbon dating, suggest that the excreta dug up at the Traversette site could date to well within the ballpark of the Punic forces’ traverse.

“Since Allen’s conclusions at times rest on the slippery slopes of conjecture, what they add up to is open to considerable interpretation. Andrew Wilson, of the Institute of Archaeology at the University of Oxford, maintains that the date range doesn’t follow from the data presented, and that the MAD layer could have accumulated over several centuries. Allen, is unfazed. “I believe in hypothesis-driven science,” he says. “Naturally, some people are going to be skeptical of our deductions and say they are — for lack of a better word — crap. Which is perfectly healthy, of course. Skepticism is what science is all about.”

“Hannibal’s Mire lies in a soft, enclosing gorge about the size of a soccer pitch. The sides of the surrounding hills splinter into a small stream that purls through moss and ferns and peat hags. For all the stark drama — shadows scudding across cliffs, sudden shafts of sharpening air, clouds draping heavily over peaks — the bog creates a sense of serenity.“So far, the research team has isolated five tapeworm eggs from the muck. Genome sequencing of the eggs is high on Allen’s to-do list. “The more genetic information we have, the more precise we can be about what type of animal left the droppings and perhaps its geographic origin,” he says. If Allen can link the DNA to a horse that comes only from Africa or Spain, he’ll be satisfied that he’s on the right track. If he can link it to an elephant — improbable considering that horses are spooked by pachyderms and require separate space to forage — he would really be in business. Or possibly not. Hannibal’s kid brother Hasdrubal followed him 11 years later and brought war elephants along, too. As you might have anticipated, there’s no clear consensus on whether Hasdrubal took the exact same path, so finding an elephant tapeworm wouldn’t definitively prove the route was Hannibal’s.

Hannibal’s Invades Italy and Defeats the Romans

Hannibal finally reached the valley of the Po, with only twenty thousand foot and six thousand horse. Here he recruited his ranks from the Gauls, who eagerly joined his cause against the Romans. When the Romans were aware that Hannibal was really in Italy, they made preparations to meet and to destroy him. Sempronius was recalled with the army originally intended for Africa; and Scipio, who had returned from Massilia, gathered together the scattered forces in northern Italy and took up his station at Placentia on the Po. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Hannibal won three battles in Italy but lost the forth. Early Carthaginian victories left 15,000 Romans dead in one place and 20,000 in another. With their superior cavalry and what became textbook usage of bottlenecking tactics, Hannibal's forces defeated the Roman force of Flamininius in 217 B.C. at Lake Trasimene. Next he humiliated the Romans, by coldly coordinating his infantry and cavalry attacks, at Cannae in northern Italy, where 60,000 Romans were killed. This victory drew the north of Italy from Rome's sphere for some time.

These victories were followed by a massacre of 50,000 legionnaires (from an army of 75,000) at the Trebia River. Here the Roman were surrounded by flanking movements on both sides. Hannibal's genius killed 6000 legionnaires in minutes. After the stunning defeats, one Roman army was annihilated and Rome was nearly destroyed. The Romans were worried that Hannibal would take his revenge in most awful way. The statesmen Quintus Fabius Maximus was put in charge of the Roman army.

Hannibal spent a total of 15 years in Italy and although he was able to defeat the Romans in key battles he was ultimately defeated because the Romans had a large population to draw new recruits from and Carthage's mercenary forces shrank as time went on. The Roman armies under Fabius followed the Carthaginians and wore them down with delaying and harassing tactics. During the Battle of the Metaurus, Hannibal and his brother were defeated at the Metaurus River by 7,000 Romans in 207 B.C.

Aurelius. For in the time of those magistrates Carthaginian envoys came to Rome, to return thanks to the Roman senate and people for having made peace with them; and as a mark of gratitude they presented them with a golden crown, at the same time asking that their hostages might live at Fregellae and that their prisoners should be returned. To them, in accordance with a decree of the senate, the following answer was made: that their gift was received with thanks; that the hostages should live where they had requested; that they would not return the prisoners, because Hannibal, who had caused the war and was bitterly hostile to the Roman nation, still held command in their army, as well as his brother Mago. Upon receiving that reply the Carthaginians recalled Hannibal and Mago to Carthage. On his return Hannibal was made a king, after he had been general for twenty-one years. For, as is true of the consuls at Rome, so at Carthage two kings were elected annually for a term of one year.

“In that office Hannibal gave proof of the same energy that he had shown in war. For by means of new taxes he provided, not only that there should be money to pay to the Romans according to the treaty, but also that there should be a surplus to be deposited in the treasury.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024