Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.)

SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.)

Hannibal

The Second Punic War, which occurred 23 years after the First Punic War, was arguable the most important of the Punic Wars. While the First Punic War was primarily an opening round battle primarily over the territory of Sicily, the Second Punic War was viewed as a test of Rome’s power over who would control Europe. At that time Rome and Carthage were struggling for supremacy in the western Mediterranean. The trigger for the conflict was the rapid growth of the Carthaginian dominion in Spain. While Rome was adding to her strength by the conquest of Cisalpine Gaul and the reduction of the islands in the sea, Carthage was building up a great empire in the Spanish peninsula, where it was raising new armies, with which to invade Italy. This policy was launched of the great Carthaginian military commander Hamilcar Barca and was continued by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, who founded the city of New Carthage (Cartagena, Spain) as the capital of the new province. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

In the Second Punic War, 218-201 B.C., Carthage was anxious to get revenge after the first Punic War. But in the end Rome supplanted Carthage as the predominate power in the Mediterranean. The war was a major milestone in evolution of Rome from a republic into an imperial power. Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: ““The Romans declared war on Carthage again in 218 B.C., by which time Hamilcar had been killed in battle and Hannibal was in charge of the army. In the opening phase of PWII, Hannibal consolidated and expanded control of the territory in Spain. Since the Romans had mastery of the seas, he attempted the unthinkable: attacking their homeland by surprise from the supposedly impregnable north. Hoping that the sight of rampaging elephants would scare the enemy, he assembled his animal train and headed east. “Sitting on his cot Hannibal could feel the rhythm set in motion by his troops as his squadrons Marched past,” Mahaney writes in The Warmaker. In a flurry of purple prose, he adds: “The empty water jug, like a fortress, teetered slightly on the shelf, reacting very differently than water. Yes, he thought, my army will be like a fluid enveloping all stationary objects, rolling like a wave over them.” [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2017]

The Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage were pivotal in making Rome a great empire. They began in 264 B.C., and lasted for 118 years with Rome ultimately prevailing. There were three Punic wars. They are regarded as the first world wars. The number of men employed, the strategies and the weapons employed were like nothing that ever been seen before. "Punic" come from the Roman word for "Phoenician, " a reference to Carthage.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PUNIC WARS AND HANNIBAL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): ROME AND CARTHAGE BATTLE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND SICILY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL: HIS LIFE, ACHIEVEMENTS AGAINST ROME, EXILE, DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS: ELEPHANTS, POSSIBLE ROUTES AND HOW HE DID IT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CARTHAGE VICTORIES IN THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF CANNAE: TACTICS, FIGHTING, IMPACT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THIRD PUNIC WAR: ROME DECISIVELY DEFEATS CARTHAGE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hannibal’s War: A Military History of the Second Punic War” by J. F. Lazenby (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Punic Wars” by Andrian Goldworthy (2001) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Punic Wars” by Dexter Hoyos Amazon.com;

“Hannibal's Road: The Second Punic War in Italy, 213–203 BC”

by Mike Roberts (2020) Amazon.com;

“Hannibal” by Patrick N Hunt (2018) Amazon.com;

“Hannibal: Rome's Greatest Enemy” by Philip Freeman (2023) Amazon.com;

“Pride of Carthage” by David Anthony Durham (Doubleday, 2005), a historical novel about Hannibal Amazon.com;

"The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2007) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Carthaginian Wars 265-146 BC” by Terence Wise, Richard Hook (Illustrator) (1982) Amazon.com;

“Carthage: A History” by Serge Lancel (1997) Amazon.com;

“Rome Versus Carthage: The War at Sea” by Christa Steinby (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Roman Republic 264–30 BC: History, Organization and Equipment

by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome From Romulus to Augustus” by Philip Matyszak Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“Carthage Must be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization” by Richard Miles (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

Hannibal and the Beginning of the Second Punic War

In 218 B.C., Hannibal left his base in base in Spain and led a force of mercenaries with elephants through the south of Gaul (France) and across the Alps in the winter. This marked the beginning of the Second Punic War. The elephants had little impact on the fight but they scored a psychological blow for the Carthaginians giving them an aura of power and invincibility.

Hannibal's invasion route

Rome began to be alarmed when Carthage began extending its territory toward the north from southern Spain.. Rome induced Carthage to make a treaty not to extend her conquests beyond the river Iberus (Ebro), in the northern part of Spain. Rome also formed a treaty of alliance with the Greek city of Saguntum, which, though south of the Iberus, was up to this time free and independent. Carthage continued the work of conquering the southern part of Spain, without infringing upon the rights of Rome, until Hasdrubal died. Then Hannibal, the young son of the great Hamilcar, and the idol of the army, was chosen as commander. This young Carthaginian, who had in his boyhood sworn an eternal hostility to Rome, now felt that his mission was come. He marched from New Carthage and proceeded to attack Saguntum, the ally of Rome; and after a siege of eight months, captured it. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Hannibal's father Hasdrubal had (together with his father-in-law Hamilcar) began the conquest of Spain in the south, supposedly with his little boy (Hannibal) at his side. When Hamilcar died in 228 Hasdrubal took over the war effort. When Hasdrubal died in 221, the 21 year old Hannibal took over. The climax of his pushes to the west and north was the successful assault on Saguntum, which occurred while Rome was busy in Illyria. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ]

The Romans sent an embassy to Carthage to demand the surrender of Carthage rejected the Roman embassy demanding Hannibal be given up in reparation for Saguntum, Hannibal. The story is told that Quintus Fabius, the chief Roman envoy, lifted up a fold of his toga and said to the Carthaginian senate, “Here we bring you peace and war; which do you choose?” “Give us either,” was the reply. “Then I offer you war,” said Fabius. “And this we accept,” shouted the Carthaginians. Thus was begun the most memorable war of ancient times.

Rome was now at war, not only with Carthage, but with Hannibal. The first Punic war had been a struggle with the greatest naval power of the Mediterranean, but the second Punic war was to be a conflict with one of the greatest soldiers that the world has ever seen. As a military genius, no Roman could compare with him. If the Romans could have known what ruin and desolation were to follow in the train of this young man of Carthage, they might have hesitated to enter upon this war. But no one could know the future. While Carthage placed her cause in the hands of a brilliant captain, Rome felt that she was supported by a courageous and steadfast people. It will be interesting for us to follow this contest between a great man and a great nation. \~\

Hannibal

Hannibal Hannibal (247-183 B.C.) was a cagey strategist who came close to destroying Rome through his military skill and cheeky audacity. He played a pivotal role in one the greatest what-if moments in world history. Napoleon regarded Hannibal as the greatest military man of antiquity. Not only did he outmaneuver the great Roman legions, he managed the logistics of getting his army through the Alps to surprise Rome. Hannibal came within a whisker of defeating Rome. If he had won the world might have had a more difficult time spelling a Carthaginian Empire than a Roman one.

Hannibal was the son of Hamilcar Barca. Hamilcar Barca rebuilt Carthage after the first Punic War. Lacking the means to rebuild the Carthaginian fleet he built an army in Spain. Before taking power, Hannibal was reportedly required by his father to forever be an enemy of Rome. Reportedly he stood before an altar and swore: “I will follow the Romans both at sea and on land. I will use fire and metal to arrest the destiny of Rome.

Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “The Histories”: “Of all that befell the Romans and Carthaginians, good or bad, the cause was one man and one mind — Hannibal. For it is notorious that he managed the Italian campaigns in person, and the Spanish by the agency of the elder of his brothers, Hasdrubal, and subsequently by that of Mago, the leaders who killed the two Roman generals in Spain about the same time. Again, he conducted the Sicilian campaign first through Hippocrates and afterwards through Myttonus the Libyan. So also in Greece and Illyria: and, by brandishing before their faces the dangers arising from these latter places, he was enabled to distract the attention of the Romans thanks to his understanding with King Philip [Philip V, King of Macedon]. So great and wonderful is the influence of a Man, and a mind duly fitted by original constitution for any undertaking within the reach of human powers.” [Source: Polybius, “The Histories of Polybius”, 2 Vols., translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (London: Macmillan, 1889), I.582-586]

The historian Oliver J. Thatcher wrote: “Rome, with the end of the third Punic war, 146 B. C., had completely conquered the last of the civilized world. The best authority for this period of her history is Polybius. He was born in Arcadia, in 204 B. C., and died in 122 B.C. Polybius was an officer of the Achaean League, which sought by federating the Peloponnesus to make it strong enough to keep its independence against the Romans, but Rome was already too strong to be resisted, and arresting a thousand of the most influential members, sent them to Italy to await trial for conspiracy. Polybius had the good fortune, during seventeen years exile, to be allowed to live with the Scipios. He was present at the destructions of Carthage and Corinth, in 146 B. C., and did more than anyone else to get the Greeks to accept the inevitable Roman rule. Polybius is the most reliable, but not the most brilliant, of ancient historians.”

See Separate Articles: HANNIBAL europe.factsanddetails.com

;

Western Mediterranean at the time of the Second Punic War

Hannibal Crosses the Alps

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Initially the Roman strategy was to contain the Carthaginians in northern Spain and southern Gaul from their base at Pisa, while simultaneously campaigning in Africa, where an expeditionary force was to gather local support and block the lines of resupply (probably not, as Polybius believes, to attack Carthage itself). Needless to say, Hannibal had other ideas. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

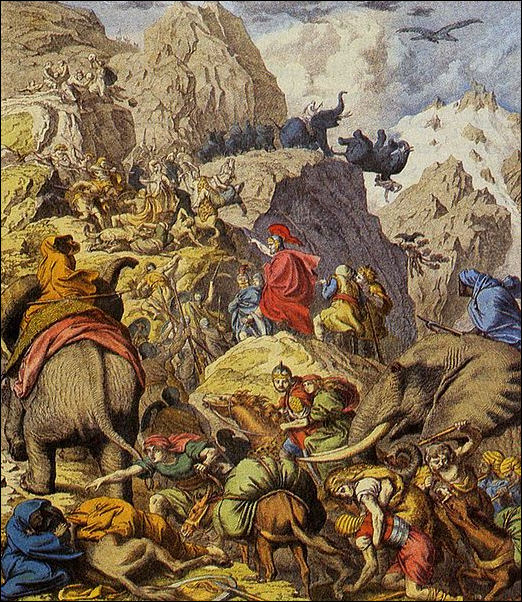

From his base in Spain Hannibal led a force of mercenaries with elephants through the south of Gaul (France) and across the Alps in the winter of 218 B.C. This marked the beginning of the Second Punic War. The elephants had little impact on the fight but they scored a psychological blow for the Carthaginians giving them an aura of power and invincibility. Hannibal led 50,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry troops and 27 elephants across the Alps. Polybius (3.33 = SB 62) says he saw the exact number (38,000 foot and 8,000 horse) recorded on a bronze tablet set up by Hannibal. In any case, his army crossed the bridge-less Rhone and likely endured snow storms and snow drifts when it crossed the Alps. In some accounts all but one of the elephants and half of Hannibal's soldiers were killed in the Alps.

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “When he came to the Alps separating Italy from Gaul, which no one before him had ever crossed with an army except Hercules (the Greek) because of which that place is called the Greek Pass, he cut to pieces the Alpine tribes that tried to keep him from crossing, opened up the region, built roads, and made it possible for an elephant with its equipment to go over places along which before that a single unarmed man could barely crawl. By this route he led his forces across the Alps and came into Italy.” [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

No one is sure what route Hannibal took. Much of what has been written about the elephants and Alps is speculation. On the subject of Hannibal's route, Mark Twain once wrote: "The researches of many antiquarians have already thrown much darkness on the subject, and it is probable, if they continue, that we shall soon know nothing at all." Much of the imagery of Hannibal and his elephants comes from Flaubert's Salammbo .

Most scholars believe that after crossing the Alps, Hannibal’s army arrived in Italy near the source of the Po River at Col de la Traversette and caught Roman armies by surprise even though Hannibal's attack was forecast by the sacred of chickens of Claudius Pulcher. The Roman general Marcellus rode with blinds on his litter pulled down so he wouldn't send any bad omen.

See Separate Article: HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS WITH HIS ELEPHANTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Hannibal crosses the Alps

Hannibal’s Invades Italy and Defeats the Romans

Hannibal finally reached the valley of the Po, with only twenty thousand foot and six thousand horse. Here he recruited his ranks from the Gauls, who eagerly joined his cause against the Romans. When the Romans were aware that Hannibal was really in Italy, they made preparations to meet and to destroy him. Sempronius was recalled with the army originally intended for Africa; and Scipio, who had returned from Massilia, gathered together the scattered forces in northern Italy and took up his station at Placentia on the Po. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Hannibal won three battles in Italy but lost the fourth. Early Carthaginian victories left 15,000 Romans dead in one place and 20,000 in another. With their superior cavalry and what became textbook usage of bottlenecking tactics, Hannibal's forces defeated the Roman force of Flamininius in 217 B.C. at Lake Trasimene. Next he humiliated the Romans, by coldly coordinating his infantry and cavalry attacks, at Cannae in northern Italy, where 60,000 Romans were killed. This victory drew the north of Italy from Rome's sphere for some time.

These victories were followed by a massacre of 50,000 legionnaires (from an army of 75,000) at the Trebia River. Here the Roman were surrounded by flanking movements on both sides. Hannibal's genius killed 6000 legionnaires in minutes. After the stunning defeats, one Roman army was annihilated and Rome was nearly destroyed. The Romans were worried that Hannibal would take his revenge in most awful way. The statesmen Quintus Fabius Maximus was put in charge of the Roman army.

See Separate Articles: CANNAE AND KEY BATTLES OF THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com

Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae

Romans Turns the Tide Against Carthage in the Second Punic War

Hannibal spent a total of 15 years in Italy and although he was able to defeat the Romans in key battles he was ultimately defeated because the Romans had a large population to draw new recruits from and Carthage's mercenary forces shrank as time went on. The Roman armies under Fabius followed the Carthaginians and wore them down with delaying and harassing tactics. During the Battle of the Metaurus, Hannibal and his brother were defeated at the Metaurus River by 7,000 Romans in 207 B.C.

The first ray of hope came from Spain, where it was learned that Hasdrubal had been defeated by the Scipios. Then Hannibal’s army met its first repulse in Campania. The Romans also, by forming a league with the Aetolian cities of Greece and sending them a few troops, were able to prevent Macedonia from giving any aid to Hannibal. Soon Syracuse was captured after a siege by the Roman praetor Marcellus. Moreover, Hannibal’s forces were weakened by the need of protecting his new allies, scattered in various parts of southern Italy. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: In 216 B.C., having just won over Capua, among other places, Hannibal and “his men wintered there, and according to Livy (23.18) the soft life at Capua had a deleterious effect, though Polybius says they wintered in the open. The years 215-212 B.C. in Italy are taken up by Hannibal's attempts to secure his stronghold in the south. Notable holdouts against Hannibal included Nola, Cumae (heroically defended by Ti. Sempronius Gracchus), Rhegium, and Tarentum. In 212 the Romans took the war to Hannibal by besieging his base at Capua. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

The Romans were greatly incensed by the revolt of Capua, and determined to punish its citizens. Regular siege was laid to the city, and two Roman armies surrounded its walls. Hannibal marched to the relief of the beleaguered city and attempted to raise the siege; but could not draw the Roman army from its intrenchments. As a last resort, he marched directly to Rome, hoping to compel the Romans to withdraw their armies from Capua for the defense of the capital. Although he plundered the towns and ravaged the fields of Latium, and rode about the walls of Rome, the fact that “Hannibal was at the gates,” did not entice the Roman army away from Capua. Rome was well defended, and Hannibal, having no means of besieging the city, withdrew again into the southern part of Italy.

After Capua fell to the Romans in 211 B.C.. ; its chief citizens were put to death for their treason, many of the inhabitants were reduced to slavery, and the city itself was put under the control of a prefect. Silverman wrote: “Livy gives a vivid account of the extremely harsh measures taken by Rome to make an example of Capuan perfidy: the leaders were executed and the rest sold into slavery. Capua and its environs became ager publicus (Livy 26. 16 = SB 64). Still, Hannibal's efforts to weaken the Roman network of alliances in Italy continued to bear fruit. In 212 B.C., twelve Latin colonies refused to send troops for the levy.’ Even so Capua showed could not protect his Italian allies; and his cause seemed doomed to failure, unless he could receive help from his brother Hasdrubal, who was still in Spain. By 209 B.C. Tarentum, which Hannibal had taken in 213, was recaptured. The following year saw the death of Marcellus, the hero of Sicily, then consul for the fourth time.

Battle of the Metaurus (207 B.C.)

Hasdrubal (Hannibal's brother) had been kept in Spain by the vigorous campaign which the Romans had conducted in that peninsula under the two Scipios. Upon the death of these generals, the young Publius Cornelius Scipio was sent to Spain and earned a great name by his victories. But Hasdrubal was determined to go to the rescue of his brother in Italy. He followed Hannibal’s path over the Alps into the valley of the Po. Hannibal had moved northward into Apulia, and was awaiting news from Hasdrubal. There were now two enemies in Italy, instead of one. One Roman army under Claudius Nero was, therefore, sent to oppose Hannibal in Apulia; and another army under Livius Salinator was sent to meet Hasdrubal, who had just crossed the river Metaurus, in Umbria. \~\

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “In 207 Hasdrubal finally managed to cross the Alps with 30,000 troops. The plan was for the brothers to link up in Apulia, but this design was thwarted by the bold action of the consul C. Claudius Nero. Nero left Hannibal unopposed in Apulia and raced north to intercept Hasdrubal, whom he met at the battle of the Metaurus River (207 B.C.). This time the Roman numerical advantage (both consular armies had combined for the occasion) was put to better use, and Nero was able to outflank Hasdrubal, who died on the field. Another attempt to reinforce Hannibal followed, with Mago landing at Genoa in Cisalpine Gaul; but he was turned back at Ariminium, and Hannibal simply hung on in the south, losing one town after another. Finally in 203, after 15 years on Italian soil, Hannibal returned to Africa to face the younger Scipio (later to be called Africanus). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

It was necessary that Hasdrubal should be crushed before Hannibal was informed of his arrival in Italy. The consul Claudius Nero therefore left his main army in Apulia, and with eight thousand picked soldiers hurried to the aid of his colleague in Umbria. The battle which took place at the Metaurus was decisive; and really determined the issue of the second Punic war. The army of Hasdrubal was entirely destroyed, and he himself was slain. The first news which Hannibal received of this disaster was from the lifeless lips of his own brother, whose head was thrown by the Romans into the Carthaginian camp. Hannibal saw that the death of his brother was the doom of Carthage; and he sadly exclaimed, “O Carthage, I see thy fate!” Hannibal retired into Bruttium; and the Roman consuls received the first triumph that had been given since the beginning of this disastrous war. By 205 Scipio had subdued all of Spain, and returned to Rome in triumph to be elected consul. \~\

Africanus Scipio, the Man Who Defeated Hannibal

Africanus Scipio

Of all the men produced by Rome during the Punic wars, Publius Cornelius Scipio (afterward called Africanus) came the nearest to being a military genius. From boyhood he had, like Hannibal, served in the army. At the death of his father and uncle, he had been intrusted with the conduct of the war in Spain. With great ability he had defeated the armies which opposed him, and had regained the entire peninsula, after it had been almost lost. With his conquest of New Carthage and Gades, Spain was brought under the Roman power. On his return to Rome, Scipio was unanimously elected to the consulship. He then proposed his scheme for closing the war. This plan was to keep Hannibal shut up in the Bruttian peninsula, and to carry the war into Africa. Although this scheme seemed to the aged Fabius Maximus as rash, the people had entire confidence in the young Scipio, and supported him. From this time Scipio was the chief figure in the war, and the senate kept him in command until its close. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Scipio had arrived in Spain in 210 at age 25 with an extraordinary and unconstitutional grant of proconsular imperium (an important precedent for later figures, especially Pompey). By 209 he had captured the Carthaginian stronghold in southern Spain, Carthago Nova (New Carthage). The local soldiers believed that the waters of the lagoon by the city, which they had forded at low tide, had miraculously receded for Scipio, who was believed to enjoy the special favor of the gods; on this occasion it was Neptune who helped Scipio, but he was most closely associated with Jupiter Capitolinus (see esp. Livy 26. 19). On a more practical plane, Scipio had carried out tactical innovations in the maniples, including the wider use of the javelin (pilum) and the Spanish short sword. In 207 the Carthaginian commanders accepted a pitched battle at Ilipa. Seeming to borrow a page from Hannibal's book, Scipio used a delaying tactic with his Spanish troops in the center while the Roman flanks surrounded the enemy.”^*^

Scipio now organized his new army, which was made up largely of enthusiastic volunteers. He was for attacking in Africa at once, but it took him over a year to overcome the opposition of the cautious Fabius Maximus.

Hannibal Returns to Carthage

While the war was progressing in Africa, Hannibal still held his place in Bruttium like a lion at bay, or maybe a rat in a corner. In the midst of misfortune, he was still a hero. He kept control of his devoted army, and was faithful to his duty when all was lost. Carthage was convinced that her only hope was in recalling Hannibal to defend his native city. Hannibal left Italy in 203 B.C., the field of his brilliant exploits, and landed in Africa. Thus Rome was relieved of her dreaded foe, who had brought her so near to the brink of ruin. \~\

Hannibal

Cornelius Nepos wrote in “De Viribus Illustris”: “Then, undefeated, he was recalled to defend his native land; there he carried on war against Publius Scipio, the son of that Scipio whom he had put to flight first at the Rhone, then at the Po, and a third time at the Trebia. With him, since the resources of his country were now exhausted, he wished to arrange a truce for a time, in order to carry on the war later with renewed strength. He had an interview with Scipio, but they could not agree upon terms. A few days after the conference he fought with Scipio at Zama. Defeated incredible to relate he succeeded in a day and two nights in reaching Hadrumetum, distant from Zama about three hundred miles. In the course of that retreat the Numidians who had left the field with him laid a trap for him, but he not only eluded them, but even crushed the plotters. At Hadrumetum he rallied the survivors of the retreat and by means of new levies mustered a large number of soldiers within a few days. [Source: Cornelius Nepos (c.99-c.24 B.C.), “Hannibal, from “De Viribus Illustris,” translated by J. Thomas, 1995, Iowa State]

“While he was busily engaged in these preparations, the Carthaginians made peace with the Romans. Hannibal, however, continued after that to command the army and carried on war in Africa until the consulship of Publius Sulpicius and Gaius Aurelius. For in the time of those magistrates Carthaginian envoys came to Rome, to return thanks to the Roman senate and people for having made peace with them; and as a mark of gratitude they presented them with a golden crown, at the same time asking that their hostages might live at Fregellae and that their prisoners should be returned. To them, in accordance with a decree of the senate, the following answer was made: that their gift was received with thanks; that the hostages should live where they had requested; that they would not return the prisoners, because Hannibal, who had caused the war and was bitterly hostile to the Roman nation, still held command in their army, as well as his brother Mago. Upon receiving that reply the Carthaginians recalled Hannibal and Mago to Carthage. On his return Hannibal was made a king, after he had been general for twenty-one years. For, as is true of the consuls at Rome, so at Carthage two kings were elected annually for a term of one year.

“In that office Hannibal gave proof of the same energy that he had shown in war. For by means of new taxes he provided, not only that there should be money to pay to the Romans according to the treaty, but also that there should be a surplus to be deposited in the treasury.”

Scipio and the Romans Invade North Africa

Scipio and Romans embarked from Sicily and landed in Africa in 204 B.C.. He was assisted by the Numidian king, Masinissa, whom he had previously met in Spain; and whose royal title was now disputed by a rival named Syphax, an ally of Carthage. The title to the kingship of Numidia thus became mixed up with the war with Carthage. Scipio and Masinissa soon defeated the Carthaginian armies in Africa, and the fate of Carthage was sealed. \~\

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “ Having weathered the political opposition, Scipio sailed for Africa in 204 from his consular province (Sicily). Landing at Utica, he joined forces with the Numidian king Masinissa, whose support he had wooed and won while in Spain (the beginning of a long and sometimes rocky relationship between Rome and Numidia). But Masinissa's rival, his nephew Scyphax, remained loyal to Carthage. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“The first major encounter took place at the Great Plains (Campi Magni). The battle had three stages. Scipio began with his three divisions (hastati, principes, triarii) in line ahead and the cavalry bunched at the rear. The hastati then pressed ahead to engage the Celtiberians in the center while the other two files, ordinarily massed in the center in support of the hastati, held back long enough to allow them to advance along the sides of the infantry battle. As the hastati held the center, this produced an encirclement which needed only the rush of the cavalry to the rear to be completed. One main accomplishment here was the ouster of the loyalist Scyphax, which permitted Masinissa to make a substantial contribution of troops. the other was that the peace party at Carthage, acting before Hannibal and Mago could get back to Africa, made a treaty with Scipio on unfavorable terms: the Carthaginians were to evacuate Gaul and Spain, reduce their navy to a token 20 vessels, recognize Masinissa as the Numidian King, and give up their economic empire. ^*^

At Rome the Senate was delighted, and favored ratifying the peace (contra Livy 30. 23); but in North Africa the return of Hannibal combined with an attack on some ambassadors from Scipio to dismantle it. Scipio was unwilling to force the issue until he could take advantage of Masinissa's Numidian cavalry, which at the moment (in 203) was at home. Hannibal was not unaware of this factor, and his move to Zama was an attempt to engage Scipio before the juncture with Masinissa could be effected. Unfortunately for Hannibal, Scipio and Masinissa managed to link up just in time. ^*^

Battle of Zama

The Second Punic War ended when Hannibal was defeated by the Roman general Scipio who counterattacked in Northern Africa and routed the Carthaginian army at the Battle of Zama in 202 B.C. in Tunisia where the Romans employed a checkerboard formation to absorb an elephant charge and then counter-attacked. This was Hannibal's Waterloo.

At Zama, Hannibal fought at a great disadvantage. His own veterans were reduced greatly in number, and the new armies of Carthage could not be depended upon. Scipio changed the order of the legions, leaving spaces in his line, through which the elephants of Hannibal might pass without being opposed. In this battle Hannibal was defeated, and the Carthaginian army was annihilated. It is said that twenty thousand men were slain, and as many more taken prisoners.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “For the battle at Zama there are two competing accounts, one reflected by both Appian and Dio Cassius, the other by Polybius (15. 9-14) and Livy (30. 32-35). As frequently, the latter is more coherent. Scipio thwarted the elephantine threat by leaving lanes in his ranks through which the beasts might pass, while Hannibal tried to guard against encirclement by keeping his best troops (the veterans from Italy) to the rear. According to Polybius many of the elephants panicked at the outset and charged back into Hannibal's lines; this probably has at least a grain of truth, but it also looks like the product of the popular superstition about Scipio' special favor in the eyes of the gods. The decisive move occurred late in the battle when the Numidian horse left off chasing the remnants of Hannibal's mounted troops (most of them also Numidians) and attacked his rear. After this decisive defeat on African soil Carthage was compelled to accept terms, which were substantially the same as the treaty of 204, except that now the indemnity was doubled to 10,000 talents (payable over 50 years), and the Carthaginians agreed not to wage war outside of Africa. Even within Africa they were to undertake campaigns only with the prior approval of the Senate and people of Rome. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“The lasting effect which Hannibal's sojourn in Italy had upon the collective memory of the Romans may be inferred from the prophetic words, woven by Virgil in the early years of Augustus' principate, which the angry Dido shouts as a curse at the fleeing Aeneas (Aeneid 4. 625-629):

May some avenger arise from my bones,

To harass the Dardan settlers with fire and sword,

Now or in future, whenever the resources are there;

I pray, may our shores oppose their shores, our waves

Their waves, our arms their arms. May future generations

carry on the fight. ^*^

Hannibal’s Defeat and End of the Second Punic War (201 B.C.)

According to a peace treaty of 201 B.C. that ended the second Punic War, Carthage had to promise forever to refrain from capturing and training North African elephants. The entire Carthaginian fleet was towed out to see and burned and Carthaginian aristocrats were forced pay reparations out of their own pockets. After the Second Punic War, Carthage turned its attention to trading and became rich and prosperous once again.

The terms imposed by Scipio the terms of peace included: 1) Carthage was to give up the whole of Spain and all the islands between Africa and Italy; 2) Masinissa was recognized as the king of Numidia and the ally of Rome; (3) Carthage was to pay an annual tribute of 200 talents for fifty years; (4) Carthage agreed not to wage any war without the consent of Rome. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Battle of Zama fighting

Rome thus became the main power of the western Mediterranean. Carthage, although not reduced to a province, became a dependent state. Syracuse was added to the province of Sicily, and the territory of Spain was divided into two provinces, Hither and Farther Spain. Rome had, moreover, been brought into hostile relations with Macedonia, which paved the way for her conquests in the East. \~\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024