Home | Category: Roman Empire and How it Was Built / Government and Justice

ROMAN EMPIRE

Wenceslas_Hollar_-_.jpg) The Roman Empire refers to the state that was centered in the city of Rome and included vast territories under Roman rule. By most reckonings the Roman Empire was formed in 27 B.C. by Augustus (63 B.C.–AD 14) after the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., and lasted to A.D. 476, when Romulus Augustulus, the last ruler of the Western Roman Empire, was deposed. At its height, the empire stretched from Mesopotamia in the east to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain) in the west, and from the Rhine and Danube rivers in the north to the coast of Africa in the south, and had a population of sixty to one hundred million people. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The Roman Empire refers to the state that was centered in the city of Rome and included vast territories under Roman rule. By most reckonings the Roman Empire was formed in 27 B.C. by Augustus (63 B.C.–AD 14) after the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., and lasted to A.D. 476, when Romulus Augustulus, the last ruler of the Western Roman Empire, was deposed. At its height, the empire stretched from Mesopotamia in the east to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain) in the west, and from the Rhine and Danube rivers in the north to the coast of Africa in the south, and had a population of sixty to one hundred million people. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The Romans adopted many elements of ancient Greece culture but their government was based on military power and Roman law. Arguably in terms of technology and culture, Roman civilization was not surpassed in Europe until the Renaissance. The Roman empire was at its height in the second and third centuries A.D. At that time it included North Africa (by the conquest of Carthage in the three Punic Wars, 264-146 B.C.), the Holy Land, Egypt, Iberia (Spain), Gaul (France, conquered by Caesar in 56-49 B.C.), Britain (claimed in 43 A.D.), Asia Minor (Turkey), Macedonia (Greece) and Dacia (former Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, conquered in A.D. 117).

The Roman Empire was the first great western super power. At its height it counted at least 50 million subjects and covered about two millions square miles (about half the size of modern China). Since the dawn of recorded history, the Western world had been composed of city-states — small political entities that often fought and sacked another and resisted attempts to forge large empires. China and Persia created huge land empires in the centuries before Christ.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FALL OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC AND RISE OF IMPERIAL ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EVOLUTION OF ROMAN GOVERNMENT AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CITIZENS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN REPUBLIC GOVERNMENT: HISTORY, CONCEPTS, INFLUENCES, STRENGTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STRUCTURE OF THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT: BRANCHES, CONSULS, SENATE, ASSEMBLIES, COMITIA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO (105-43 B.C.): LIFE, CAREER, WRITINGS, LEGACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POLITICS IN ANCIENT ROME: CAMPAIGNS, PATRONAGE, CORRUPTION AND ORATORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PROPAGANDA IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Government of the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook” (Routledge) by Barbara Levick Amazon.com;

“Rome: The Center of Power, 500 B.C. to A.D. 200" by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, translated by Peter Green Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome: Infographics” by Nicolas Guillerat, John Scheid (2021) Amazon.com;

Rome, the Greek World, and the East: Volume 2: Government, Society, and Culture in the Roman Empire” by Fergus Millar, Hannah M. Cotton, Guy MacLean Rogers (2004) Amazon.com;

“Money and Government in the Roman Empire” by Richard Duncan-Jones (2010)

Amazon.com;

“Imperial Institutions in Ancient Rome and Early China: A Comparative Analysis”

by Michael Loewe, Michael Nylan, T. Corey Brennan Amazon.com;

“The Rise of the Roman Empire (Penguin Classics) by Polybius, translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire” by Anthony Everitt (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire: Economy, Society and Culture” by Peter Garnsey, Richard Saller, et al. (2014) Amazon.com;

“Rome: An Empire's Story” by Greg Woolf (2012) Amazon.com

“The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire from the First Century A.d. to the Third” by Edward N. Luttwak (1976) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire 1st Edition

by Janet Huskinson (1999) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“The Twelve Caesars” (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius (121 AD) Amazon.com

“Enemies of the Roman Order: Treason, Unrest, and Alienation in the Empire” by Ramsay MacMullen Amazon.com

“Rome in the Late Republic” by Mary Beard and M Crawford (1999) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

Size, Population and Longevity of the Roman Empire

Under Trajan (ruled A.D. 98 to 117), the Roman Empire reached the peak in terms of size — 5 million square kilometers (1.9 million square miles). Rome controlled the North African coast, Egypt, Southern Europe, and most of Western Europe, the Balkans, Crimea, and much of the Middle East, including Anatolia, Levant, and parts of Mesopotamia and Arabia. That empire was among the largest empires in the ancient world, with an estimated 50 to 90 million inhabitants, roughly 20 percent of the world's population at the time. [Source Wikipedia]

Various calculations have been made as to populations in Rome, Italy, or the empire in general during the Roman Empire. Most scholars still generally accept the estimates made by K. J. Beloch in 1886 — 1) between 750,000 and 1 million in the city of Rome in the early empire, 2) between five and eight million in Italy; and 3) between 50 and 60 million for the empire as a whole. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Road in Leptis Magna, Libya What was so extraordinary about the Roman Empire was not it size — other conquerors such as the Mongols ruled larger empires — but it is longevity. Rome presided over a large empire made up of multitude of races and ethnic groups for nearly five centuries. In contracts, the great empires of the Mongols, Spain and England lasted for only a few centuries at the most.

The main thing that differentiated the Romans from Greeks was their ability to unify as a people and generate a large standing army of paid professionals that step by step created an empire. The Greeks, who spent most of the time fighting among themselves, never really created an empire. (Alexander wasn't really a Greek, but a semi-barbarian Macedonian).

Alexander the Great was the first western leader to forge a great empire but his empire splintered soon after his death. "Alexander the Great's Empire fell, in part, because he treated his provincial subjects as defeated enemies," wrote journalist T.R. Reid in National Geographic. "The Romans treated their subjects as Romans — not outsiders but contributors. From Britannia, Arabia, Germania, and Aegygptus came authors and lawyers, teachers and physicians, engineers and soldiers to build a better empire. The Roman state was a multicultural melting pot,"

Transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: The Roman Empire was preceded by the Roman Republic, but the transition from the latter to the former was not simply a matter of installing an emperor; rather, it was an incremental process of change in which a republican government was replaced with an autocratic system. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The last century of the Republic left Rome in disarray: violence, lawlessness, and civil strife had destroyed the Republic’s political processes. Thus, as the first emperor of Rome, Augustus embarked on a massive reorganization of Roman systems with the aim of establishing law and order. Indeed, he ushered in what became known as the Pax Romana (Roman peace), a nearly two-hundred-year period of relative peace. Such calm would have been unthinkable only decades earlier.

Augustus built a foundation for his rule by consolidating political power in himself. At the same time, he maintained the veneer of the old republican political institutions by preserving the Senate, popular assemblies, and magisterial offices, though over time these bodies became more ceremonial than functional, merely rubber-stamping the decrees of the emperor. Augustus also reshaped the Senate, reducing its number from over one thousand to six hundred by weeding out senators he considered unworthy and handpicking its membership.

The period of peace and prosperity inaugurated by Augustus persisted until the end of the second century, the high-water mark of the Roman Empire. By this time, the empire had attained an unprecedented degree of organization and unity — a remarkable achievement for such a large and diverse set of territories. This unity was attributed directly to the emperor: whereas under the Republic Romans’ chief loyalty had been to the state and its institutions, under the empire the emperor himself became their primary allegiance. Throughout the empire, cults were formed to worship the emperor and his family.

The emperors from Augustus through Marcus Aurelius (121–180) continued to strengthen their position and prerogatives. Many emperors came up through the military, and they used the power of the army to secure their rule. By the second century the emperor was named in public documents as dominus noster (Our Master), and his decrees were legally binding — indeed, all laws came from the emperor in the form of edicts, judgments, and mandates, known collectively as constitutiones principium. Increasingly, imperial appointees took on the positions once held by magistrates under the Republic.

Pax Romana and Relative Peace During the Roman Empire

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: The first great achievement of the Roman Empire, Pax Romana, was notable for what did not occur. From approximately 27 B.C. to AD 180 — the reign of Augustus through that of Marcus Aurelius — the Roman Empire enjoyed relative peace, the longest such period in Western history before or since. During this period Rome prospered economically and culturally and witnessed the construction of several prominent buildings, such as the Colosseum, which was built between 70 and 82. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Pliny the Elder coined the phrase: "the immeasurable majesty of the Roman peace". "Roman peace" (pax Romana ) was not an inaccurate term. While there were military operations and rebellions, the Roman army dealt with them efficiently and everyday life for most people in the Roman Empire was not affected by them.

There were some rebellions in the provinces. There was a revolt in Pannonia in a.d. 6, which required the attention of Tiberius. There was the revolt in Judea at the end of Nero's reign, which is described by Josephus, and in 115–117 there was another Jewish revolt that started in Cyrene sparked by the appearance of a "Messiah." It spread to Egypt, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia and led to great loss of life. A third revolt, led by bar kokh ba, broke out in Judea in 132 that caused heavy losses to the Roman army and according to the historian Cassius Dio 580,000 Jews were slain. After the revolt was suppressed, Hadrian changed the name of the province from Judea to Syria Palaestina. There was a revolt in Roman Britain (60 a.d.) led by Queen Boudicca of the Iceni, which broke out when the Romans plundered the kingdom of the Iceni after its client king died and maltreated the queen and her two daughters.

The northern regions of Roman Britain was a turbulent area in the Antonine period. There was also low-level resistance: brigands and robber bands, who fed on the discontent of the under classes, often made travel overland unsafe. Yet the revolts of Rome's subjects were relatively few. In general, we may agree with Edward Gibbon's appraisal in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (ch. 2): "But the firm edifice of Roman power was raised and preserved by the wisdom of the ages. The obedient provinces of Trajan and the Antonines were united by laws and adorned by arts. They might occasionally suffer from the partial abuse of delegated authority, but the general principle of government was wise, simple, and beneficent." Gibbon goes on (ch. 3) to make a judgment which is much quoted: "If a man were called to fix the period in the history of the world, during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the death of Domitian to the accession of Commodus."

Roman Empire Government

The Roman Empire was governed by an autocracy (government by one person) centered on the position of the emperor. J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: The Senate, the dominant political institution of the Roman Republic, which preceded the empire, was retained by the emperor but lacked real political power. The hallmark of the Roman Empire was its extensive system of imperial administration, which included a hierarchy of magistrates and provincial governors. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The emperor was known as the princeps (first citizen) during the first two centuries of the empire. Under this system, called the principate, the emperor consolidated the political power of several offices that had existed under the Republic: He took on the executive functions and imperium (absolute authority) of the consul (chief magistrate) and the religious authority of the pontifex maximus (high priest). Additionally, the emperor was invested with two other types of absolute authority: imperium proconsulare, governorship and command of the provinces, and imperium proconsulare maius, the power to trump any magistrate anywhere in the empire. Over time, the emperor took on all lawmaking authority.

The emperor convened an imperial council (Consilium Principis) composed of the consuls, other magistrates, and fifteen senators chosen by lots every six months, as an advisory committee; however, this body had no policy-making authority. The Senate acted as the governing council and dominant institution of government. It dealt with foreign embassies, made binding decrees, served as the state’s highest court, and elected urban magistrates; indeed, it even had the power to name the emperor. However, the Senate was stripped of any real political power; it served chiefly to preserve the veneer of the old republican institution. Under Augustus the membership of the Senate was reduced from more than one thousand to six hundred, and over time, its composition reflected the changing empire — the Senate began to include members of the equestrian (or equite) class (a sort of lower aristocracy), as well as representatives from Italy and the provinces. Senators were primarily appointed by the emperor.

Roman Empire Administration

How did the Romans keep such a large empire with such a diverse population unified for so long? The Romans developed well-designed, logical and tolerant system of governing. Even though the Romans could meet out punishment with cruelty and brutality, they preferred cooperation and tolerance because "it worked better.” When Rome conquered a city state or a kingdom, the defeated general and his army were taken away in chains, but almost everyone else was spared. .

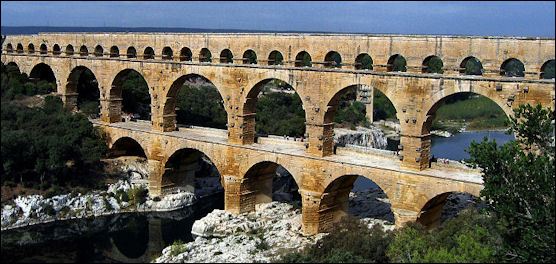

British historian Andrew Wallace-Hadrill told in National Geographic, when the Romans "had conquered the world, they turned out to be cleverer than anybody else at organizing and maintaining an empire." Romans consolidated small kingdoms into imperial provinces, constructed large masonry buildings, built good roads, established a reliable system of law, coinage and tax collection. The Roman Empire remained intact and even thrived when there were internal problems back in Rome. Even so the Emperors had no tolerance for people who revolted

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: One of the hallmarks of the Roman Empire was its extensive system of imperial administration. The progression of magistrates up the political career ladder was known as the cursus honorum. Entry-level officers served on the Vigintiviri (board of twenty) for a term of one year before moving on to higher positions. Officers who were elected quaestor, the next position up the line, were also granted membership in the Senate; these magistrates kept the treasury, maintained public records, or served as provincial governors. In the city of Rome municipal services (such as the grain dole) were handled by a trained professional civil service. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Finally, the vast territories of the Roman Empire were managed by provincial governors. The Senate supervised so-called public provinces, which were administered by governors called proconsuls who were chosen by lot and served for one year. Imperial provinces with significant military forces were considered to be under the direct supervision of the emperor, who hand-picked their governors. Still other imperial provinces were governed by prefects from the equestrian class.

Equestrian Order and Plebs Urbanus

J. A. S. Evans wrote: The term "equestrian order" (ordo equestris) is used in two senses. Strictly speaking, it was the 18 centuries of equites equo publico which once made up the cavalry of the Roman army, but their military function had been lost long ago and now they were only voting units in the Centuriate Assembly. Augustus tried to revitalize the equites equo publico, enlarging its number from 1,800 to 5,000 and reviving the annual march past, where the consuls inspected them. But in popular parlance and, in due time, officially as well, all freeborn citizens assessed at a minimum of 400,000 sesterces were equites, enjoying equestrian privileges such as the equestrian gold ring and the first 14 rows of seats in the theater. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Augustus drew a number of his officials from their ranks. Augustus recruited his prefects from the equites with the exception of the urban prefect, the chief constable of Rome and commander of the three urban cohorts of security police, who was a senator and ex-consul. There were the two prefects of the Praetorian Guard, the prefect of Egypt, which Augustus ruled directly, the prefects of the Roman fleets, one based at Misenum on the Gulf of Naples and the other at Ravenna, the prefect of the night patrol (vigiles), and the prefect of the grain supply (praefectus annonae).

Also recruited from the equites were Augustus' deputies, the procuratores, who might act as his private financial agents or govern small provinces. Small provinces in Alpine districts or Judaea were governed initially first by prefects but later by procurators. Pontius Pilate is designated a procurator in the Gospels, but in fact his title is proved to have been "prefect" by an inscription found in Jerusalem. It can hardly be true, however, that Augustus established a cursus honorum for the equites which paralleled that of the senators, for we can discern no regular path of promotion.

Beneath the equestrians in the Roman social hierarchy was the plebs urbanus, "the common people of city of Rome" who were entitled to a free distribution of grain every month until 2 B.C., when this privilege was restricted to a fixed group, the plebs frumentaria numbering eventually about 150,000. But beyond the city, the population of the empire was made up of freeborn citizens, freedmen, and provincials. All Italians were now citizens and increasing numbers of provincials were beginning to acquire it as well. Freedmen, that is, manumitted slaves who bore the family names of their former masters, were citizens with qualifications: they were, for instance, excluded from public office and military service. Augustus retained the disabilities for freedmen; yet the corps of 7,000 night watchmen (vigiles) which he instituted in A.D. 6 were all freedmen, and in the crises of Pannonian revolt of A.D. 6 and the disaster in the Teutoberg forest in A.D. 9, he recruited them into special cohorts in the army. But they did not become legionary soldiers. However, he allowed many Italian towns to institute the seviri Augustales, an annual board of six freedmen who looked after the cult of the Lares Augusti ; contributions from them for public works and spectacles were expected in return. Later, under the emperor Claudius (81–54) freedmen were to capture positions of great power in the imperial bureaucracy, but under Claudius' successors, a shift in favor of equestrians began again, culminating with the emperor Hadrian.

Roman Empire Government in Rome, Italy and the Provinces

J. A. S. Evans wrote: In Rome, the three urban cohorts of 1,000 men each under the urban prefect's command kept law and order. The city was divided into 14 regions (regiones) which were subdivided into precincts (vici). There were 265 vici. Seven cohorts of vigiles, established in A.D. 6, combined the duties of a night watch and a fire brigade. Augustus also found that the people expected him to ensure adequate supplies of water and food and eventually he appointed a prefect of the grain supply. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

In Italy, which now included Cisalpine Gaul, was divided into 11 administrative regions, but these remained more important geographically than politically. Begun by Julius Caesar, the reform of the municipal constitutions — there were 474 municipalities in the peninsula — was completed by Augustus, and it set the model for new foundations and for incorporated towns in the provinces. The municipal governments were modeled roughly on Rome's; there were chief magistrates (duoviri or quattuorviri) and a senate (curia). A large number of young men of the leading families in the Italian municipalities were incorporated into the senatorial and equestrian orders at Rome and furnished a supply of new recruits for administrative careers. Augustus wanted Rome and Italy to enjoy a favored position in the empire, and unlike Caesar, he granted the franchise citizenship to provincials.

As for the provinces, an agreement between Augustus and the Senate in 27 B.C. instituted a sort of dual governance for the provinces: some, generally those not threatened by enemies or internal disturbance, would be ruled by the senate, and Augustus governed the remainder, appointing legates to administer them. Governors of senatorial provinces would be chosen from the ranks of exconsuls or ex-praetors; their term was one year, and they were accompanied by quaestors as financial officials. For the imperial provinces, Augustus chose his legates from senators who were ex-consuls or ex-praetors, and they held office at his pleasure. They could be moved from one province to another without any interruption in their career.[Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Therefore, senatorial provinces were theoretically governed in the same way as they were in the Roman republic before the Civil Wars, and Augustus had republican precedent for this procedure as well. Although Pompey had become governor in Spain in 53 B.C., he remained in Rome and ruled through legates in his provinces. However, Augustus could use his maius imperium to lay down rules in senatorial provinces if he wished. This is made dramatically clear by the Cyrene Edicts (SEG ix, 8). An inscription found in Cyrene in 1927 gives us four edicts of Augustus, (7/6 B.C.), which set forth regulations relating to friction between Greeks and Romans: the first specifically gives instructions to the provincial governor in the senatorial province of Crete and Cyrene and his successors.

The borders of the Augustan empire were not clearly marked, and beyond the provinces were the client states. In Germany beyond the Rhine, the Roman government manipulated the German tribes by tying friendly chiefs to them, rewarding them with Roman citizenship and subsidies, and fostering divisions where it was to Rome's advantage. Until the disaster of the Teutoberg Forest in A.D. 9, Rome intended to subdue the territory between the Rhine and the Elbe rivers, and after that objective had to be abandoned, Rome still sought to establish a control mechanism over the German chiefs. In the east, client kings were manipulated ruthlessly. Unsatisfactory kings were removed. Even generally satisfactory ones could fall at the whim of an emperor. Gaius Caligula (37–41) who was free-handed at bestowing kingdoms on his friends, deposed and executed Ptolemy of Mauretania, a descendant of Antony and Cleopatra, and annexed his kingdom. It is hard to discover a rational reason for his action. Client kingdoms had advantages: they masked the reality of the Roman yoke, and they conserved the army's manpower by relieving it of police duties in border areas. But the client-state system was in full decline by the end of the first century.

Roman Empire and the World

Roman coins have been found all over Asia and ancient Chinese coins have been found in Rome. By A.D. 100, Greek and Roman mariners were sailing east of India. It is not that farfetched of an idea that Roman vessels in the Atlantic were blown off course to America.

China and Rome were vaguely aware of each other. But no official direct government contacts are known to have taken place. One Roman traveler wrote: "there is a very great inland city called Thina from which silk floss, yarn and cloth are shipped...It is not easy to get to this Thina, for rarely do people come from it, and only a few.” One of the earliest known contacts between the Roman Empire and Chinese Empire was in the second century B.C. when a Chinese trade official established ties along the Silk Road route. During this period Persian controlled strategic trade centers in the Middle East.

Maps were solely for the use of the government. They were thought of as so valuable that it was a crime for an ordinary person to possess one. Among the fantastic places described by Pliny the Elder were the Ear Islands off of Germany where fisherman were reported to have to such large ears they wrapped their bodies with them like cloaks. Germany was also said to be the home of a mule-like creature that had such long upper lips they “cannot feed except walking" backwards. It was believed that below the equator there were people with huge feat who could use them to shade themselves when they laid down on the ground. Creature that inhabited the four corners of the earth included tribes of people with eight-toed feet turned backwards and men with dogs' heads and talons for fingers who "barked for speech." [Source: The Discoverers]

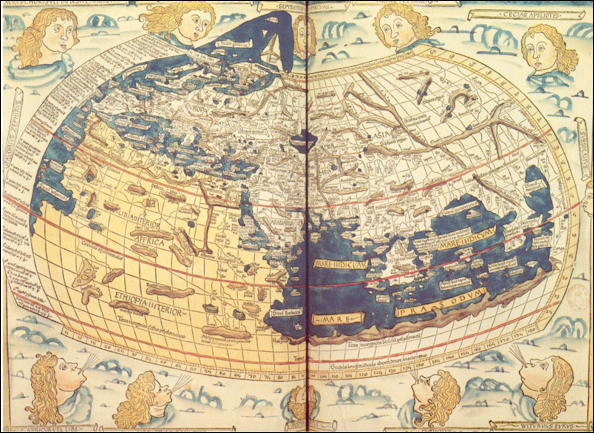

World of Ptolemy as shown by Johannes de Armsshein, Ulm 1482

Christianity in the Roman Empire

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: The Roman Empire was of particular importance for Christianity, because Christ was born under the reign of Augustus, and the early Church developed in the milieu of Greco-Roman civilization within the Roman Empire and was subject to its government. Indeed, the New Testament is an important source for the life of the common people in the first century of the Empire. In Late Antiquity, the Roman Empire collapsed in Western Europe, and the year 476, when the last emperor of Rome was dethroned, has become a date of convenience for the fall of the Roman Empire. In the eastern Mediterranean, however, the Roman Empire continued, developing seamlessly into the Byzantine Empire which lasted until Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Up into the nineteenth century, Greeks still called themselves 'Romaioi ' (Romans). [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Christianity emerged in the Roman Empire during a period of cultural conflict, economic dislocation, political change and migration from the countryside to the cities. Farming villages were being consolidated into large plantations causing a great deal of social dislocation as previously independent farmers were transformed into serflike tenant farmers.

While Roman authorities were promoting universal allegiance to an imperial power, early Christian missionaries provided al alternative of self-supporting communities whose aim was to create a kingdom of God.

Constantine (A.D. 312-37) is generally known as the “first Christian emperor.” The story of his miraculous conversion is told by his biographer, Eusebius. It is said that while marching against his rival Maxentius, he beheld in the heavens the luminous sign of the cross, inscribed with the words, “By this sign conquer.” As a result of this vision, he accepted the Christian religion; he adopted the cross as his battle standard; and from this time he ascribed his victories to God, and not to himself. The truth of this story has been doubted by some historians; but that Constantine looked upon Christianity in an entirely different light from his predecessors, and that he was an avowed friend of the Christian church, cannot be denied. His mother, Helena, was a Christian, and his father, Constantius, had opposed the persecutions of Diocletian and Galerius. He had himself, while he was ruler in only the West, issued an edict of toleration (A.D. 313) to the Christians in his own provinces. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

See Category: CHRISTIANIZED ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com

European Provinces of the Roman Empire

1) Western.

Spain (205-19 B.C.).

Gaul (France, Belgium, parts of Germany, 120-17 B.C.).

Britain (A.D. 43-84).

2) Central.

Rhaetia et Vindelicia (roughly Switzerland, northern Italy15 B.C.).

Noricum (Austria, Slovenia, 15 B.C.).

Pannonia (western Hungary, eastern Austria, northern Croatia, north-western Serbia, northern Slovenia, western Slovakia and northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. A.D. 10).

3) Eastern.

Illyricum (northern Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and coastal Croatia, 167-59 B.C.).

Macedonia (northern Greece, modern Macedonia, 146 B.C.).

Achaia (western Greece, 146 B.C.).

Moesia (Central Serbia, Kosovo, northern modern Macedonia, northern Bulgaria and Romanian Dobrudja 20 B.C.).

Thrace (northeast Greece, A.D. 40).

Dacia (Romania, A.D. 107). \~\

Romans in North Africa and West Asia

The Romans claimed: 1) North Africa after the Punic Wars (264 – 146 B.C.), 2) Greece, Macedonia, Syria and Asia Minor after the Macedonian Wars (214–148 B.C.); and 3) Egypt after the struggle between Octavian (Augustus) and Marc Antony and Cleopatra VII (Cleopatra) and the Battle of Actium (31 B.C.).

African Provinces of the Roman Empire

Africa proper (Libya, former Carthage, 146 B.C.).

Cyrenaica and Crete (74, 63 B.C.).

Numidia (Algeria, small parts of Tunisia, Libya, 46 B.C.).

Egypt (30 B.C.).

Mauretania (western Algeria, Morocco, A.D. 42). \~\

The Romans claimed: 1) North Africa after the Punic Wars (264 – 146 B.C.), 2) Greece, Macedonia, Syria and Asia Minor after the Macedonian Wars (214–148 B.C.); and 3) Egypt after the struggle between Octavian (Augustus) and Marc Antony and Cleopatra VII (Cleopatra) and the Battle of Actium (31 B.C.).

Asiatic Provinces of the Roman Empire

1) In Asia Minor (Anatolia, modern Turkey)

Asia proper (western Turkey133 B.C.).

Bithynia et Pontus (northern Turkey, south of the Black Sea, 74, 65 B.C.).

Cilicia (southeast coast of Turkey, 67 B.C.).

Galatia (central Turkey, 25 B.C.).

Pamphylia et Lycia (southwest Turkey, 25, A.D. 43).

Cappadocia (eastern Turkey, A.D. 17).

2) In Southwestern Asia.

Syria (64 B.C.).

Judea (Israel, 63 - A.D. 70).

Arabia Petraea (A.D. 105).

Armenia (A.D. 114).

Mesopotamia (A.D. 115).

Assyria (A.D. 115). \~\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024