Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.) / Age of Augustus / Roman Empire and How it Was Built / Government and Justice

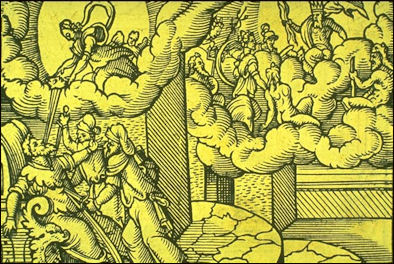

FALL OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC AND RISE OF IMPERIAL ROME

4.jpg)

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: The Roman Empire was preceded by the Roman Republic, but the transition from the latter to the former was not simply a matter of installing an emperor; rather, it was an incremental process of change in which a republican government was replaced with an autocratic system. The last century of the Republic left Rome in disarray: violence, lawlessness, and civil strife had destroyed the Republic’s political processes. Thus, as the first emperor of Rome, Augustus embarked on a massive reorganization of Roman systems with the aim of establishing law and order. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Mary Beard, a classics professor at Cambridge University, wrote in a BBC History online article, “In 133 BC, Rome was a democracy. Little more than a hundred years later it was governed by an emperor. This imperial system has become, for us, a by-word for autocracy and the arbitrary exercise of power. At the end of the second century BC the Roman people was sovereign. True, rich aristocrats dominated politics. In order to become one of the annually elected 'magistrates' (who in Rome were concerned with all aspects of government, not merely the law) a man had to be very rich. Even the system of voting was weighted to give more influence to the votes of the wealthy. Yet ultimate power lay with the Roman people. Mass assemblies elected the magistrates, made the laws and took major state decisions. Rome prided itself on being a 'free republic' and centuries later was the political model for the founding fathers of the United States. [Source: Mary Beard, BBC History, BBC, March 29, 2011]

By A.D. 14 AD, when Augustus died, popular elections had all but disappeared. Power was located not in the old republican assembly place of the forum, but in the imperial palace. The assumption was that Augustus's heirs would inherit his rule over the Roman world - and so they did. Augustus's rule, however, ushered in what became known as the Pax Romana (Roman peace), a nearly two-hundred-year period of relative peace. Such calm would have been unthinkable only decades earlier.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CITIZENS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN REPUBLIC GOVERNMENT: HISTORY, CONCEPTS, INFLUENCES, STRENGTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN EMPIRE: SIZE, GOVERNMENT, ADMINISTRATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STRUCTURE OF THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT: BRANCHES, CONSULS, SENATE, ASSEMBLIES, COMITIA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EVOLUTION OF ROMAN GOVERNMENT AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO (105-43 B.C.): LIFE, CAREER, WRITINGS, LEGACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POLITICS IN ANCIENT ROME: CAMPAIGNS, PATRONAGE, CORRUPTION AND ORATORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PROPAGANDA IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire” by Anthony Everitt (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

"Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Rome: An Empire's Story” by Greg Woolf (2012) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of An Empire” by Simon Baker (2007) Amazon.com

“The Punic Wars” by Andrian Goldworthy (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2007) Amazon.com;

“Roman Conquests: Macedonia and Greece” by Philip Matyszak Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“The Twelve Caesars” (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius (121 AD) Amazon.com

“Histories” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Enemies of the Roman Order: Treason, Unrest, and Alienation in the Empire” by Ramsay MacMullen Amazon.com

“Rome in the Late Republic” by Mary Beard and M Crawford (1999) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republics” by Harriet I. Flower (2009) Amazon.com

“A History of the Roman Republic” by Cyril E. Robinson (2013) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

Roman Republic

Rome was a village and the Romans were one of many Italic tribes around 500 BC

The Romans established a republic in 509 B.C. The quasi-representative form of government during the Republic era was comprised of bicameral legislature with: 1) a “comitia” , an assembly of representatives made up of elected male citizens, many of them military men; and 2) "the Senate and the People of Rome,” made up of representatives elected to one-year terms. Most of the Senate members were patricians, members of upper classes. The seat of the government was in the "capitol." The Republican form of government endured for 460 years (509 to 49 B.C) until Julius Caesar absolved it.

Starting in the third century B.C., the Senate was the most powerful political body in Rome and it stayed that way for 150 years until Caesar seized control in 48B.C. and established himself as a dictatorial emperor, a trend that continued until Rome fell.

The Senate consisted of hundreds of members who served for life. It was sort of like the House of Lords in the British Parliament and senators were required by law to have a large fortune. "Not unexpectedly," wrote historian Lionel Casson, "they traditionally came from a circumscribed number of famous old families. For centuries this narrow circle of wealthy aristocrats was the establishment, Elections simply determined which among them would fill the higher offices and whose sons would get the lower."

During the third and fourth centuries B.C. politics was a gentlemanly affair. There were also people's assemblies that passed legislation and administered jurisdictions. Later these popular assemblies "fell into disuse" and power was centered in the Senate. [Source: Lionel Casson, Smithsonian]

Book: “The Twelve Caesars” by Michael Grant.

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY ROMAN REPUBLIC: ITS FOUNDING, DEVELOPMENT AND EXPANSION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LAST THREE KINGS OF EARLY ROME: LEGENDS, ETRUSCAN ORIGINS, VIOLENCE, UPHEAVAL europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PLEBEIANS AND PATRICIAN IN THE EARLY ROMAN REPUBLIC europe.factsanddetails.com ;

GOVERNMENT OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC: HISTORY, CONCEPTS, INFLUENCES, STRENGTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STRUCTURE OF THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT: BRANCHES, CONSULS, SENATE, ASSEMBLIES, COMITIA europe.factsanddetails.com

Decline of the Republic

“Many Romans themselves put the key turning point in 133 BC,” Beard wrote. “This was the year when a young aristocrat, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, held the office of 'tribune' (a junior magistracy which had originally been founded to protect the interests of the common people). As one ancient writer put it, this was when 'daggers first entered the forum'. [Source: Mary Beard, BBC History, BBC, March 29, 2011]

The course of events is clear enough. Gracchus proposed to distribute to poor citizens stretches of state-owned land in Italy which had been illegally occupied by the rich. But instead of following the usual practice of first consulting the 'senate' (a hugely influential advisory committee made up of ex-magistrates), he presented his proposal directly to an assembly of the people. In the process, he deposed from office another tribune who opposed the distribution and argued that his reforms should be funded from the money that came from the new Roman imperial province of Asia.

Roman Republic in 44 BC

Gracchus's land bill was passed. But when he tried to stand for election for another year's term as tribune (a radical step - as one of the republican principles was that each office should be held for one year only), he was murdered by a posse of senators. Gracchus's motivation is much less clear. Some modern historians have seen him as a genuine social reformer, responding to the distress of the poor. Others have argued that he was cynically exploiting social concerns to gain power for himself. Whatever his motives were, his career crystallised many of the main issues that were to underlie the revolutionary politics of the next hundred years.

In 133 B.C., and the years that followed," Lionel Casson wrote, "the situation changed radically. First reformers broke away from the Establishment. Then ambitious figures from outside it...made their way into politics by getting the rank and fill behind them. Reformers and new men not only entered contests for higher office, but succeeded in bypassing the Senate by resuscitating the long-dormant people's assemblies. [Source: Lionel Casson , Smithsonian magazine]

The events of 133 BC were followed by a series of intensifying crises. In 123-122 BC, Tiberius's brother Gaius was elected to the tribunate, introduced a whole package of radical legislation, including state-subsidised corn rations - and was also murdered. The original republican government with democratic features added in 4th and 5th centuries B.C. slowly disappeared as a strong central government was needed to maintain order in the face of class conflict, slave revolts (135, 75), murders, assassinations, social reforms, and civil war (Caesar vs. Pompey, Caesar’s assassins vs. triumvirates, Octavian vs. Antony).

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROME AFTER THE PUNIC WARS (AFTER 146 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WARS IN ROME IN THE 2ND AND 1ST CENTURIES B.C.: REVOLTS, MASSACRES, MARIUS, MITHRADATE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SULLA: WARS, MASSACRES, DICTATORSHIP, THE PRECURSOR OF CAESAR? europe.factsanddetails.com

Challenge of the Roman Army

Mary Beard wrote in a BBC History online article, “The consequences of Rome's growing empire were crucial. Many of the poor had fallen into poverty after serving for long periods with armies overseas - and returning to Italy to find their farmland taken over by wealthier neighbours. How were the needs of such soldiers to be met? Who in Rome was to profit from its empire, which already stretched from Spain to the other end of the Mediterranean? [Source: Mary Beard, BBC History, BBC, March 29, 2011]

Tiberius's decision to use the revenues of Asia for his land distribution was a provocative claim - that the poor as well as the rich should enjoy the fruits of Rome's conquests. But Tiberius's desire to stand for a second tribunate also raised questions of personal political dominance. The state had few mechanisms to control men who wanted to break out of the carefully regulated system of 'power sharing' that characterised traditional Republican politics.

59.jpg) This became an increasingly urgent issue as leading men in the first century BC, such as Julius Caesar, were sometimes given vast power to deal with the military threats facing Rome from overseas - and then proved unwilling to lay down that power when they returned to civilian life. There seemed to be no solution for curbing them apart from violence.

This became an increasingly urgent issue as leading men in the first century BC, such as Julius Caesar, were sometimes given vast power to deal with the military threats facing Rome from overseas - and then proved unwilling to lay down that power when they returned to civilian life. There seemed to be no solution for curbing them apart from violence.

At the end of the century Gaius Marius, a stunningly successful soldier, defeated enemies in Africa, Gaul and finally in Italy, when Rome's allies in Italy rebelled against her.He held the highest office of state, the consulship, no fewer than seven times, an unprecedented level of long-term dominance of the political process.

Marius then came into violent conflict with Lucius Cornelius Sulla, another Roman warlord, who after victories in the east actually marched on Rome in 82 BC and established himself 'dictator'. This had been an ancient Roman office designed to give a leading politician short terms powers in an emergency. Sulla held it for two years, in the course of which he had well over a thousand of his political opponents viciously put to death. Unlike Julius Caesar, however, who was to become dictator 40 years later, Sulla retired from the office and died in his bed.

Pompey Versus Caesar

Caesar

Mary Beard wrote in a BBC History online article, “The middle years of the first century BC were marked by violence in the city, and fighting between gangs supporting rival politicians and political programmes. The two protagonists were Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus ('Pompey the Great', as he was called, after Alexander the Great) and Julius Caesar. Originally allies, they became bitter enemies. Both had conquered vast tracts of territory: Pompey in what is now Turkey, Caesar in France. Caesar promoted radical policies in the spirit of Tiberius Gracchus; Pompey had the support of the traditionalists. [Source: Mary Beard, BBC History, BBC, March 29, 2011]

Historians in both the ancient and modern world have devoted enormous energy to tracking the precise stages by which these two men came head-to-head in civil war. For much of this period we can actually follow the daily course of events thanks to the surviving letters of a contemporary politician, Marcus Tullius Cicero.

But the fact is that, given the power each had accrued and their entrenched opposition, war between them was almost inevitable. It broke out in 49 BC. By the end of 48 BC, Pompey was dead (beheaded as he tried to land in Egypt) and Caesar was left - to all intents and purposes - as the first emperor of Rome.

But not in name. Using the old title of 'dictator', he notoriously received the kind of honours that were usually reserved for the gods. He also embarked on another programme of reform including such radical measures as the cancellation of debts and the settlement of landless veteran soldiers.He did not, however, have long to effect change (perhaps his most lasting innovation was his reform of the calendar and the introduction of the system of 'leap years' that we still use today). For in 44 BC he too was murdered by a posse of senators, in the name of 'liberty'.

Not much 'liberty' was to follow. Instead there was another decade of civil war as Caesar's supporters first of all battled it out with his assassins, and when they had been finished off, fought among themselves. There was no other major player left when in 31 BC Octavian (Caesar's nephew and adopted son) defeated Antony at a naval battle near Actium in northern Greece.

See Separate Article: CAESAR, POMPEY AND CRASSUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Caesar Crosses the Rubicon

After Julius Caesar finished subduing Gaul in 51 B.C., he defied the Republican tradition of victorious Roman generals not being allowed to return to Rome with their armies out of fear they would try to overthrow the government, which is exactly what Caesar did.

While Caesar was away in Gaul, Crassus was killed and Pompey became leader. Pompey wielded great power and declared Caesar a public enemy and ordered him to disband his army. Caesar refused. When he moved his army from Gaul into Rome’s formal territory, it was interpreted as a declaration of war against Rome. Caesar reached the border of greater Rome at the Rubicon River. He then he plunged his horse in the water, shouting , “The die is caste.”

By crossing the Rubicon Caesar declared war on the political establishment of his day. For many historians it marked the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire. To this day “crossing the Rubicon” describes a decision from which there is no return.

By crossing the Rubicon Caesar gambled that he could not only beat his military rival Pompey but also could also outmaneuver conservative politicians like Cicero and Cato. Some historians say Caesar’s move marked the end of period in which foreign adventures created larger armies and more powerful generals and it was only a matter of time until they threatened the political status quo.

Book: “Rubicon — The Last Years of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (Doubleday, 2004)

See Separate Article: CAESAR, THE CROSSING OF THE RUBICON AND THE SITUATION IN ROME AT THE TIME europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Civil Wars and the Beginning of Roman Emperor Under Caesar

Caesar marched into Rome with his army in and seized control of the government and the treasury and declared himself dictator while Pompey, in command of the Roman navy, fled to Greece. Five years of civil war followed.

Caesar defeated Pompey in a series of land battles that took place throughout the Roman empire over a four years period. After Caesar led a successful campaign in Iberia (Spain), he defeated Pompey in Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt. The Ptolemies refused to provide quarter for a loser and had him executed and cut off his head.

This made Caesar the unchallenged leader. Caesar said, “It is more important for the state that I should survive...I have long had my fill of power and glory; but should anything happen to me, Rome will enjoy no peace.”

Caesar’s campaign in Gaul allowed Rome to claim France, the Netherlands and Belgium. In campaigns early in the Civil Wars period he claimed Portugal, Spain, and Greece. With Egypt under the control of Cleopatra, Caesar set his sights on the Middle East.

After annihilating the Parthians in Pontus and Zela in the Middle East in 47 B.C., Caesar sent home the immortal message, "”Veni, vidi, vici” ("I came, I saw, I conquered"). This victory allowed him to claim Syria, Israel, and western Turkey. Afterwards he returned home to Rome to fight another rival, Cato, who had gone to North Africa to raise an army to challenge Caesar. That didn’t happen. Instead, Caesar sent his army to Africa and crushed Cato.

In 46 B.C., the last of Pompey’s forces were defeated in Spain. With the civil wars over Caesar was the unchallenged leader of Rome. In the meantime Portugal, Spain, France, the Netherlands Belgium, Italy, Greece, Syria, Israel, western Turkey, and northern Libya were added to Rome under Caesar, making it a truly great empire.

See Separate Article: CIVIL WAR AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com

Augustus, Emperor

Augustus cameo Mary Beard wrote in a BBC History online article, “During his 40-year rule, Octavian established the political structure that was to be the basis of Roman imperial government for the next four centuries. Some elements of the old republican system, such as magistracies, survived in name at least. But they were in the gift of the emperor ( princeps in Latin). [Source: Mary Beard, BBC History, BBC, March 29, 2011]

He also directly controlled most of the provinces of the Roman world through his subordinates, and he nationalised the army to make it loyal to the state and emperor alone. No longer was it to be possible for generals, like Pompey or Caesar, to enter the political fray with their troops behind them.

There was a good deal of clever spin here. The princeps rebranded himself, getting rid of the name 'Octavian', and the past associations of civil war, and called himself 'Augustus' instead - an invented name which meant something like 'blessed by the gods'. No less important, like many autocrats since, he invested heavily in reshaping the city of Rome with massive building projects advertising his rule, while poets sang the praises of him and the new Rome. He spared no effort promoting his family as a future imperial dynasty.

Augustus was both canny and lucky. When he died in 14 AD, aged well over 70, he was succeeded by his stepson, Tiberius. By then the idea of the 'free republic' was just the romantic pipe-dream of a few nostalgics.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND HABITS factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS BECOMES EMPEROR factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS AS EMPEROR OF ROME factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS POLICIES AND REFORMS factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS, PAX ROMANA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

Roman Emperor Worship and Deification

Emperor worship was common in Rome. Starting with Augustus (27 B.C.-14 AD) emperors that considered themselves gods took over the empire. The Roman emperors seemed to believe in their divinity and they demanded that their subjects worship them. Marcellus was honored with a festival. Flaminius was made a priest for three hundred years. Ephesus had a shrine for Serilius Isauricus. Antony and Cleopatra referred to themselves as Dionysus and Osiris and named their children Sun and Moon. Caligula and Nero demanded to be worshiped like gods in their lifetime. And Vespian said on his deathbed "Oh dear, I'm afraid I'm becoming a God."

Describing the deification of Emperor Septimius Severus in A.D. 211, the Greek historian Herodian wrote: "It is a Roman custom to give divine status to those emperors who die with heirs to succeed them. This ceremony is called deification. Public mourning, with a mixture of festive and religious ritual, is proclaimed throughout the city, and the body of the dead is buried in the normal way with a costly funeral.

Caesars deification "Then they make an exact wax replica of the man, which they put on a huge ivory bed strewn with gold-threaded coverings, raised high up in the entrance to the palace. This image, in the deathly palace, rests there like a sick man...the whole Senate sitting on the left, dressed in black, while on the right are all women who can claim special honors...This continues for seven days, during each of which doctors came and approach the bed, take a look at the supposed invalid and announce a daily deterioration in his condition.”

“When at last the news is given that he is dead, the end of the bier is raised on the shoulders of the noblest members of Equestrian Order and chosen young Senators, carried along the Sacred Way, and placed in the Forum Romanum...a chorus of children from the noblest and most respected families stands facing a body of women selected on merit. Each group sings hymns and songs.”

“After this the bier is raised and carried outside the city walls to a square structure filled with firewood and "covered with golden garments, ivory decorations and rich pictures." On top of the structure are five more structures that are progressively smaller. “The whole thing was often five or six stories tall.”

"When the bier has been taken to the second story and put inside, aromatic herbs and incense of every kind produced on earth, together with flowers, grasses and juices collected for their smell, and brought and poured in heaps...When the pile of aromatic material is very high and the whole space filled...The whole equestrian Order rides round...Chariots also circle in the same formation, the charioteers dressed in purple and carrying images with the masks of famous Roman generals and emperors."

"The heir to the throne takes a brand and sets it to every building . All the spectators crowd in and add to the flame. Everything is very easily and readily consumed...From the highest and smallest story...an eagle is released and carried up into the sky with the flames. The Romans believe the bird bears the soul of the emperor from earth to heaven. Thereafter the dead emperor is worshipped with the rest of the gods."

Roman Emperor Succession

Despite the relative stability of the Roman Empire the succession from one emperor to another was often a complicated and messy affair. Most of the time the emperorship was passed on from one family member to another (such as among the Julio-Claudians and Severans). Several emperors who had no son chose their political heirs by adopting them. Other times power was seized through battles or other forms of violence. Once it was even sold to the highest bidder. Adopted emperors generally served Rome better than emperors who were blood relatives.

.jpeg)

Roman Emperor AD 41 by Alma Tadema (1871)

Did a Volcanic Eruption in Alaska Help End the Roman Republic?

Guy Middleton wrote: Julius Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March (March 15) in 44 B.C. and a bloody civil war followed. This brought down the Roman republic and replaced it with a monarchy led by Caesar’s nephew Octavian, who in 27 B.C. became the emperor Augustus. A group of scientists and historians suggest that a massive volcanic eruption in Alaska played a role in this transition, as well as helping to finish off Cleopatra’s Egypt. The study, led by Joseph R McConnell of the Desert Research Institute in Nevada, demonstrates how careful scientific research on ancient climate can add context to our more traditional scholarship. At the same time, the research raises challenging questions about how we integrate such data into historical narratives without oversimplifying the story. [Source: Guy Middleton, Visiting Fellow, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University, June 23, 2020]

“Caesar’s assassination came at a time of unrest for the ancient Mediterranean. This was exacerbated by strange atmospheric phenomena, and unusually cold, wet weather that caused crop failures, food shortages, disease, and even the failure of the annual Nile flood on which Egyptian agriculture relied. In 1988, classicist Phyllis Forsyth suggested that an eruption of Mount Etna in Sicily in 44BC was responsible for these problems because the aerosol particles released into the atmosphere would reflect sunlight back into space and cool the climate. While McConnell’s team agreed that the Etna eruption could have caused some of these disruptions, they have now argued it was a later massive eruption of the Okmok volcano in Alaska that altered the climate and helped weaken the Roman and Egyptian states. They drew on three strands of evidence to support their claim.

“The first came from ice samples taken from deep in the Arctic ice sheets, which trapped air as they formed over hundreds of thousands of years, providing a datable record of atmospheric conditions. These ice cores showed there was a spike in solid particles, dust and ash from a volcanic eruption early in 43BC. The researchers then showed the geochemical properties of these particles matched with samples from the Okmok volcano.

“For evidence for the ancient climate, they then looked at tree rings and speleothems (stalactites and stalagmites) from various parts of the northern hemisphere, including China, Europe and North America. These suggested that 43BC to 34BC was the fourth coldest decade in the last 2,500 years, and 43BC and 42BC were the second and eighth coldest years.

“Data from the research was then fed into a computer-based climate modelling system called the Community Earth System Model (CESM), which produced a climate simulation. This showed that the eruption of Okmok could have caused cooling of 0.7˚C to 7.4˚C across the southern Mediterranean and northern Africa in 43-42BC, which persisted into the 30s B.C.

“This could also have led to increased summer and autumn rainfall that would have damaged crops. At the same time, drier conditions in the upper reaches of the Nile may have led to its failure to flood in 43BC and 42BC. “In this way, McConnell’s team make a good case for Okmok’s potential impact on temperature, rainfall and a resulting change in agricultural production in 43BC and after. But the conclusions they draw about its impact on the bigger historical picture are less certain.

How a Volcanic Eruption in Alaska Could Have Impacted the Roman Republic?

Guy Middleton wrote: One of the major problems with scientific papers in which climate events are blamed for major historical changes is that they are not able to fit in much analysis of the historical issues themselves. These tend to be reduced to straightforward events or problems that can then be easily “explained” or “solved” by science. The realities, when we zoom in, are much more messy. The transition of Rome from a republic to a monarchy – via a period of rule by the competing triumvirate of Octavian, Mark Antony and Lepidus – was a long and complex process. It involved many people and parties with different motivations and plans. The whole period poses a challenge to historians and entire books have sought to describe and explain it. [Source: Guy Middleton, Visiting Fellow, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University, June 23, 2020]

“But this civil war was only the latest in a series of escalating conflicts in the later period of the republic, in which the behaviour of earlier figures, like Sulla, who had seized control of Rome decades earlier, became precedents for what might be possible. The outcome of the war and the establishment of a monarchy was not inevitable. Rather than a narrative of crisis, decline and fall, the period can even be seen as one of political experimentation, of state formation, of attempts to solve the problems that beset the republic.

This period of war relied on manpower and the capacity of state apparatus to extract and redirect food and money from society. Despite ancient sources that report difficulties with this extraction, we should remember that the machinery that enabled it remained essentially in working order. Without it, armies would not have been fed and the civil wars would not have been able to happen.

“And while the failure of the Nile floods in 43BC and 42BC would certainly have been bad, Egypt was up and running again soon after. Antony and Cleopatra were able to raise and maintain armies, fight, and were finally defeated only in 31BC in the naval battle of Actium. If people were going hungry, the conflict itself and profiteering grain dealers were perhaps more to blame than the climate (as was the case in the Ethiopian famines of the 1980s).

“The effects of Okmok’s eruption in 43BC may have been serious, as McConnell’s team argue. But it is also very clear that personal, political and military decisions – and chance – were the direct determiners of how history unfolded in Rome and Egypt. There were many points in the years after 44 B.C. at which things could have turned out quite differently, whatever the climate was like. The military activity of the period alone would seem to show that both Rome and Egypt were quite resilient, overall, in the face of natural hazards, and as states they continued to transform in an ever-changing world. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024