Home | Category: Government and Justice

ROMAN POLITICS

council meeting

Despite the relative stability of the Roman Empire the succession from one emperor to another was often a complicated and messy affair. Most of the time the emperorship was passed on from one family member to another (such as among the Julio-Claudians and Severans). Several emperors who had no son chose their political heirs by adopting them. Other times power was seized through battles or other forms of violence. Once it was even sold to the highest bidder. Adopted emperors generally served Rome better than emperors who were blood relatives.

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “We tend to think of Britain at the time of the Romans as a remote outpost on the edges of the Roman empire - a troublesome but unimportant backwater province, rather like the Hindu Kush in the British Raj. A posting here would surely mean uncomfortable conditions and dangerous assignments, in a downward-spiralling career. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. Right from its first involvement in Roman politics, Britain was a dynamic, militarised territory which attracted some of Rome's best and most ambitious men, who were on their way to the pinnacle of achievement. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“To understand this, you must understand the way that Roman politics worked. Rome's political system was based upon competition within the ruling elite. Senators competed fiercely for public office, the most coveted of which was the post of Consul. Two were elected each year to head the government of the state. Even in the imperial period this was maintained, though in fact true power lay with the emperor and his extended household. |::|

“Roman soldier During the Republic, the post of Consul was a quasi-military one: the Consuls were the commanders-in-chief of the Roman army, so military experience was of paramount importance to a Roman's political career. Military glory provided the greatest boost to any Roman's prestige and once again this carried over into the Empire. Military triumphs boosted your career, military service made you eligible for a wide range of profitable postings and for non-citizens, 25 years in the army was a guaranteed way of gaining citizenship for you and your family. |::|

“It is unsurprising then that Britain, a large island that was never fully conquered, should be seen as a land of opportunity to Romans with ambition. In fact during the imperial period, Britain was the only province in the entire empire that had a permanent garrison of more than two legions. Throughout most of its history, Britain contained three legions: IX Hispana followed by VI Victrix in York, II Augusta in Caerleon and II Adiutrix followed by XX Valeria Victrix in Chester. |::|

RELATED ARTICLES:

CICERO (105-43 B.C.): LIFE, CAREER, WRITINGS, LEGACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PROPAGANDA IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

CITIZENS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN REPUBLIC GOVERNMENT: HISTORY, CONCEPTS, INFLUENCES, STRENGTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN EMPIRE: SIZE, GOVERNMENT, ADMINISTRATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STRUCTURE OF THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT: BRANCHES, CONSULS, SENATE, ASSEMBLIES, COMITIA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FALL OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC AND RISE OF IMPERIAL ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EVOLUTION OF ROMAN GOVERNMENT AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rome: The Center of Power, 500 B.C. to A.D. 200" by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, translated by Peter Green Amazon.com;

“The Government of the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook” (Routledge) by Barbara Levick Amazon.com;

“On Government” (Penguin Classics) by Marcus Tullius Cicero, translated by Michael Grant (1994)

“Politics and Government in Ancient Rome” (Primary Sources of Ancient Civilizations). by Daniel C. Gedacht (2003) Amazon.com;

“Politics in the Roman Republic” by Henrik Mouritsen Amazon.com;

“Roman Political Thought” by Jed W. Atkins (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Republic of Letters: Scholarship, Philosophy, and Politics in the Age of Cicero and Caesar” by Katharina Volk (2004) Amazon.com;

“Caesar: Politician and Statesman” by Mattias Gelzer, Peter Needham (1968) Amazon.com;

“The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic” by Fergus Millar Amazon.com

“Women and Politics in Ancient Rome” by Richard A. Bauman (1994) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Religion and Politics in the Roman Republic” by Eric M. Orlin (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Rhetorical Studies” by Michael J. MacDonald (2017) Amazon.com;

“The State of Speech: Rhetoric and Political Thought in Ancient Rome” by Joy Connolly (2013) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Roman Rhetoric” by William Dominik and Jon Hall (2010)

Amazon.com;

“That Tyrant, Persuasion: How Rhetoric Shaped the Roman World” by J. E. Lendon (2022) Amazon.com;

“Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome's Greatest Politician” by Anthony Everitt Amazon.com

“Cicero: Selected Works” by Marcus Tullius Cicero and Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“Selected Political Speeches (Penguin Classics) by Marcus Tullius Cicero Amazon.com;

“The Politics of Munificence in the Roman Empire: Citizens, Elites and Benefactors in Asia Minor” by Arjan Zuiderhoek Amazon.com;

“Controlling Laughter: Political Humor in the Late Roman Republic” by Anthony Corbeill (2016) Amazon.com;

“Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide” by Paul Plass (1995) Amazon.com;

Political Offices in the Roman Empire

During the Republic politics must have been profitable only for those who played the game to the end. No salaries were attached to the offices, and the indirect gains from one of the lower magistracies would hardly pay the expenses necessary to secure the next office in order. Spending great sums of money on the public games had been an obvious way to win popularity so long as the people voted at elections; it continued to be a heavy obligation even when under the Empire this right to vote was taken from the people. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The gain came through positions in the provinces. The quaestorship might be spent in a province; the praetorship and consulship were sure to be followed by a year abroad. To honest men the places gave the opportunity to learn of profitable investments. A good governor was often selected by a community to look after its interests in the capital, and this meant an honorarium paid in the form of valuable presents from time to time. Cicero’s justice and moderation as quaestor in Sicily earned him a rich reward when he came to prosecute Verres for plundering that province, and when he was in charge of the grain supply during his aedileship. |+|

“To corrupt officials the provinces were gold mines. Every sort of robbery and extortion was practiced, and the governor was expected to enrich not merely himself but also the cohors that had accompanied him. Catullus complains bitterly of the selfishness of Memmius, who prevented his staff from plundering a poor province. The story of Verres may be read in any history of Rome; it differs from that of many governors only in the fate that overtook the offender. Though in the Imperial period there were great reforms in the administration of the provinces, the salaries then paid the governors did not always save the provincials from extortion.” |+|

Introduction of Secret Ballots to Ancient Rome

politcal graffiti from Pompeii

The ballot laws of the Roman Republic (Latin: leges tabellariae) were four laws which introduced the secret ballot to all popular assemblies in the Republic. They were all introduced by tribunes, and consisted of the lex Gabinia tabellaria (or lex Gabinia) of 139 B.C., applying to the election of magistrates; the lex Cassia tabellaria of 137 B.C., applying to juries except in cases of treason; the lex Papiria of 131 B.C., applying to the passing of laws; and the lex Caelia of 107 B.C., which expanded the lex Cassia to include matters of treason. [Source Wikipedia]

Prior to the ballot laws, voters announced their votes orally to a teller, essentially making every vote public. The ballot laws curtailed the influence of the aristocratic class and expanded the freedom of choice for voters. Elections became more competitive. In addition, the secret ballot made bribery more difficult.

The 130s and 120s B.C. were a turning point for Roman politics. The ballot laws were introduced at a time of rising popular sentiment that saw the rise of populist politicians (populares), who gained power by appealing to the lower classes. The most well-known of these were Tiberius Gracchus in 133 B.C. and Gaius Gracchus a decade later. The resulting conflict between populares (who operated mostly in popular assemblies) into and optimates (who operated mostly in the Senate) lead to the dissolution of political norms and the rise of political violence. Within decades, mob violence, political assassination, and even civil war would become routine. These conflicts would cause the end of the republic in 27 B.C.

Roman Politics and Political Campaigns

Before Caesar, Roman politics, in many ways, wasn't all that different from American politics today. By the second century, so many ordinary people had the right to vote that a lively political system arose, with parties, campaigns, negative advertising, billboards, and rich contributors. As is true today it helped to be wealthy. Roman politicians often sponsored sporting events before an election, making it very clear that it was their show, and sometimes pulled out all the stops by hiring big name gladiators. [Source: Lionel Casson , Smithsonian +++]

"In Cicero's day," classicist Lionel Casson wrote, "consular hopefuls behaved as politicians always have and forever will: they made themselves as visible as possible, were charming to all potential voters and promised everything to everybody." +++

The word "candidate" comes from ancient Rome. Originally candidates meant a person in white clothes. Later it was used to describe people running for public office, who often dressed in white togas to express their pure and incorrupt character. When a Roman candidate was asked if he was going to run he typically replied "maybe he would...and then again maybe he wouldn't." Or, "if it is in the best interests of the city, I will seek office." +++

With no television or radio, candidates in their search for votes made speeches wherever they could draw a crowd and cruised the forum, accompanied by a nomenclator (name caller) who whispered the name of the people that politicians was going to meet to add a personal touch to the encounter. +++

There were no political posters. Papyrus and parchment were too expensive. Slogans, however, were painted and scrawled onto walls. Messages found on the walls of buildings ran from the direct and simple (“Casellius for aedilis ” ) to the more colorful (“Genialis appeals to you to elect Bruttius Balbus duumvir , He will preserve the treasury”). Barbers, goldsmiths, fruit sellers, and even chess players trumpeted their endorsements with graffiti-like messages. There were dirty tricks and negative advertisements too. One candidates, it was scrawled, was endorsed by "all the sleepyheads," "all the drunken stay-out-lates and "sneaky thieves." +++

Cicero Brothers on Roman Political Campaigns and Candidates

"Now lets look at the polls," Cicero wrote in July 27, 54 B.C., shortly before an election, "Bribery's thriving...the interest rate has doubled...Caesar is backing Memmius with all his might...in a deal I don't dare put into writing. Pompey is fuming and growling and backing and backing Sacaurus, but who knows whether as a front of for real. None is ahead; their handouts are keeping them all even." [Source: Lionel Casson , Smithsonian]

Cicero's brother put together some tips to campaigners. "Have followers at your heels daily," he advised, "of every kind, class and age; because from their numbers people can figure out how much power and support you are going to have at the polls...make it clear you know people's names...You particularly need to use flattery. No matter how viscous and vile it is on the other days of a man's life, when he runs for office it is indispensable..."And] if you make a promise, the mater is not fixed, it's for a future date...but, of you say no, you are sure to alienate people right away and a lot of them." [Ibid]

Cicero, arguably Rome's greatest politician Quintus Cicero wrote in a letter to His Brother Marcus Cicero (Cicero), 64 B.C. “Almost every day as you go down to the Forum you must say to yourself, "I am a novus homo [i.e. without noble ancestry]. "I am a candidate for the consulship." "This is Rome." For the "newness" of your name you will best compensate by the brilliance of your oratory. This has ever carried with it great political distinction. A man who is held worthy of defending ex-consuls, cannot be deemed unworthy of the constitution itself. Therefore approach each individual case with the persuasion that on it depends as a whole your entire reputation. For you have, as few novi homines have had — all the tax-syndicate promoters, nearly the whole equestrian ordo, and many municipal towns, especially devoted to you, many people who have been defended by you, many trade guilds, and besides these a large number of the rising generation, who have become attached to you in their enthusiasm for public speaking, and who visit you daily in swarms, and with such constant regularity! [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed. Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 129-135]

“See that you retain these advantages by reminding these persons, by appealing to them, and by using every means to make them understand that this, and this only, is the time for those who are in your debt now, to show their gratitude, and for those who wish for your services in the future, to place you under an obligation. It also seems possible that a novus homo may be much aided by the fact that he has the good wishes of men of high rank, and especially of ex-consuls. It is a point in your favor that you should be thought worthy of this position and rank by the very men to whose position you are wishing to attain.

“All these men must be canvassed with care, agents must be sent to them, and they must be convinced that we have always been at one with the Optimates, that we have never been dangerous demagogues in the very least. Also take pains to get on your side the young men of high rank, and keep the friendship of those whom you already have. They will contribute much to your political position. Whosoever gives any sign of inclination to you, or regularly visits your house, you must put down in the category of friends. But yet the most advantageous thing is to be beloved and pleasant in the eyes of those who are friends on the more regular grounds of relationship by blood or marriage, the membership in the same club, or some close tie or other. You must take great pains that these men should love you and desire your highest honor.

“In a word, you must secure friends of every class, magistrates, consuls and their tribunes to win you the vote of the centuries: men of wide popular influence. Those who either have gained or hope to gain the vote of a tribe or a century, or any other advantage, through your influence, take all pains to collect and to secure. So you see that you will have the votes of all the centuries secured for you by the number and variety of your friends. The first and obvious thing is that you embrace the Roman senators and equites, and the active and popular men of all the other orders. There are many city men of good business habits, there are many freedmen engaged in the Forum who are popular and energetic: these men try with all your might, both personally and by common friends, to make eager in your behalf. Seek them out, send agents to them, show them that they are putting you under the greatest possible obligation. After that, review the entire city, all guilds, districts, neighborhoods. If you can attach to yourself the leading men in these, you will by their means easily keep a hold upon the multitude. When you have done that, take care to have in your mind a chart of all Italy laid out according to the tribes in each town, and learn it by heart, so that you may not allow any chartered town, colony, prefecture — in a word, any spot in Italy to exist, in which you have not a firm foothold.

“Trace out also individuals in every region, inform yourself about them, seek them out, secure that in their own districts they shall canvas for you, and be, as it were, candidates in your interest.

“After having thus worked for the "rural vote", the centuries of the equites too seem capable of being won over if you are careful. And you should be strenuous in seeing as many people as possible every day of every possible class and order, for from the mere numbers of these you can make a guess of the amount of support you will get on the balloting. Your visitors are of three kinds: one consists of morning callers who come to your house, a second of those who escort you to the Forum, the third of those who attend you on your canvass. In the case of the mere morning callers, who are less select, and according to present-day fashion, are decidedly numerous, you must contrive to think that you value even this slight attention very highly. It often happens that people when they visit a number of candidates, and observe the one that pays special heed to their attentions, leave off visiting the others, and little by little become real supporters of this man.

“Secondly, to those who escort you to the Forum: since this is a much greater attention than a mere morning call, indicate clearly that they are still more gratifying to you; and with them, as far as it shall lie in your power, go down to the Forum at fixed times, for the daily escort by its numbers produces a great impression and confers great personal distinction.

“The third class is that of people who continually attend you upon your canvass. See that those who do so spontaneously understand that you regard yourself as forever obliged by their extreme kindness; from these on the other hand. who owe you the attention for services rendered frankly demand that so far as their age and business allow they should be constantly in attendance, and that those who are unable to accompany you in person, should find relatives to substitute in performing this duty. I am very anxious and think it most important that you should always be surrounded with numbers. Besides, it confers a great reputation, and great distinction to be accompanied by those whom you have defended and saved in the law courts. Put this demand fairly before them — that since by your means, and without any fee — some have retained property, others their honor, or their civil rights, or their entire fortunes — and since there will never be any other time when they can show their gratitude, they now should reward you by this service.”

Pompeii Inscriptions and Graffiti About Politics and Elections

Pompeii campaign notice

William Stearns Davis wrote: “There are almost no literary remains from Antiquity possessing greater human interest than these inscriptions scratched on the walls of Pompeii (destroyed 79 A.D.). Their character is extremely varied, and they illustrate in a keen and vital way the life of a busy, luxurious, and, withal, tolerably typical, city of some 25,000 inhabitants in the days of the Flavian Caesars. Most of these inscriptions carry their own message with little need of a commentary. Perhaps those of the greatest importance are the ones relating to local politics. It is very evident that the so-called "monarchy" of the Emperors had not involved the destruction of political life, at least in the provincial towns. [Source:William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 260-265]

“The dyers request the election of Postumius Proculus as Aedile.”

“Vesonius Primus urges the election of Gnaeus Helvius as Aedile, a man worthy of pubic office.”

“Vesonius Primus requests the election of Gaius Gavius Rufus as duumvir, a man who will serve the public interest — do elect him, I beg of you.”

“Primus and his household are working for the election of Gnaeus Helvius Sabinus as Aedile.”

“Make Lucius Caeserninus quinquennial duumvir of Nuceria, I beg you: he is a good man.”

“His neighbors request the election of Tiberius Claudius Verus as duumvir.”

“The worshipers of Isis as a body ask for the election of Gnaeus Helvias Sabinus as Aedile.”

“The inhabitants of the Campanian suburb ask for the election of Marcus Epidius Sabinus as aedile.”

“At the request of the neighbors Suedius Clemens, most upright judge, is working for the election of Marcus Epidius Sabinus, a worthy young man, as duumvir with judicial authority. He begs you to elect him.”

“The sneak thieves request the election of Vatia as Aedile.

Pompeii Campaign Poster

Crassus Ruben Montoya wrote: The alleys and walls of Pompeii were alive with inscriptions, most commonly political campaign “posters” and personal greetings. Technically, these posters are depinti (painted onto plaster), intended for a broad audience, while graffiti (scratched into plaster) were handwritten by anyone, usually names and greetings to friends.[Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

Nearly 4,000 campaign posters have been documented in Pompeii, according to Rebecca Benefiel, professor of classics at Washington and Lee University. Benefiel heads the Ancient Graffiti Project, which is building an online catalog of Pompeii’s wall inscriptions. “Candidates running for office knew how to get their name out,” she says. Recent excavations in Region V uncovered more posters from municipal elections in the spring prior to the deadly eruption of A.D. 79. The inscription reads, “Vote for Helvius Sabinus as aedile [magistrate], a good man, worthy of office.” Below it is a partially excavated inscription in support of Lucius Albucius, a rival candidate. (Listen to our podcast episode about Pompeii's gossip-filled walls.)

Generally, personalized recommendations for candidates emphasized the person as “a good man” or “man of integrity.” But one stands out as a particularly interesting insight into the persuasion tactics used in Pompeii: “I ask that you vote for Gaius Julius Polybius for aedile. He brings good bread.” Since Polybius has been identified elsewhere and is not a baker, Benefiel thinks he probably paid for free bread distribution to win over voters.

Crassus, the Penultimate Corrupt Politician

One of the most powerful politicians in the era of corruption, Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 B.C.), not surprisingly was also one of the richest Roman. Born into a wealthy family, he acquired his riches, according to Plutarch, through "fire and rapine." Crassus became so powerful that he financed the army that put down the slave revolt led by Spartacus. To celebrate Spartacus's crucifixion, Crassus hosted a banquet for the entire voting public of Rome (10,000 people) that lasted for several days. Each participant was also given an allowance of three months of grain. His ostentatious displays gave us the word crass.

Crassus made a fortune in real estate by controlled Rome's only fire department acquiring the land from property owners victimized by fire.. When a fire broke out, a horse drawn water tank was dispatched to the site, but before fire was put out, Crassus or one of his representatives haggled over the price of his services, often while the house was burning down before their eyes. To save the building Crassus often required the owner to fork over title to the property and then pay rent.

Crassus was most likely the largest property owner in Rome. He also purchased property with money obtained through underhanded methods. While serving as a lieutenant in the civil war of 88-82 he able to buy land formally held by the enemy at bargain prices, sometimes by murdering its owners. Crassius also opened a profitable training center for slaves. He purchased unskilled bondsmen, trained them and then sold them as slaves for a handsome profit.

Crassus was not unlike successful modern businessmen who contribute large sums of money to a political parties in return for favors or high level government positions. He gave loans to nearly every Senator and hosted lavish parties for the influential and powerful. Through shrewd use of his money to gain political influence he reached the position of triumvir, one of the three people responsible for controlling the apparatus of state.

After attaining riches and political power the only left for Crassus to do was lead a Roman army in a great military victory. He purchased an army and sent to Syria by Caesar to battle the Parthians. In 53 B.C. Crassus lost the Battle of Carrhae, one of the Roman Empire's worst defeats. He was captured by the Parthians, who according to legend, poured molten gold down his throat when they realized he was the richest man in Rome. The reasoning of the act was that his lifelong thirst for gold should quenched in death.

Corruption in Ancient Rome

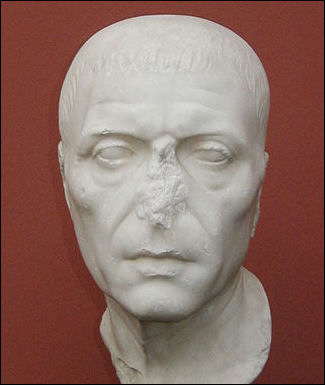

Aelius Caesar

another prominent politician Between 70 and 50 B.C., Roman politics hit rock bottom. Candidates, in some cases, dispensed with promoting sporting events and simply bought votes. The situation eventually got so out of hand that Cicero and others passed campaign reform laws that outlawed these bribes and prohibited politicians from sponsoring gladiator contests two years before an election. A candidate found guilty lost his right forever to run for office. " [Source: Lionel Casson , Smithsonian]

The Twelve Tables, an early legal code in the Roman republic, imposed the death penalty on judges who accepted bribes. Enforcement became lenient after the rise of the Roman Emperorship.

Richard Saller, a history professor at Stanford, told the New York Times, Rome “had a real problem trying to define what qualified as a bribe and what was a friendship gift. There was a pretty broad rage of quid pro quos. One Roman soldier wrote his father: "I hope to get transferred to a cohort [a cavalry unit); but here nothing gets done without money. Letters of recommendation are useless."

Emperor Tiberius tried to clamp down on local governors extorting tax payments from subjects but still left local officials plenty of room to obtain gratuities, Tiberus said he wanted his “sheep shorn, not flayed," meaning it was acceptable for local rulers to take some money but not excessive amounts.

Cicero: Letter to His Brother Quintus, 54 B.C.: “There is a fearful recrudescence of bribery. Never was there anything like it. On the 15th of July the rate of interest rose from four to eight per cent, owing to the compact made by Memmius with the consul Domitius. I am not exaggerating. They offer as much as 10,000,000 sesterces for the vote of the first century. The matter is a burning scandal. The candidates for the tribuneship have made a mutual compact; having deposited 500,000 sesterces apiece with Cato, they agree to conduct their canvass according to his directions, with the understanding that any one offending against it will be condemned to forfeit by him.” [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed. Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 129-135]

See Separate Article: CRASSUS — ANCIENT ROME'S RICHEST MAN europe.factsanddetails.com

How Political Losers Bribed Roman Emperors

Defeat is never very nice but it could be particularly nasty in ancient Rome where vanquished leaders were often paraded in the streets of Rome in chains before they killed in gruesome ways and people in conquered territory were often enslaved. Evidence from ancient Bulgaria suggests, for those near the frontiers of the Roman empire anyway, money was the sometimes the best way out.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast, “The discovery in question is a second-century Greek inscription from Nicopolis ad Istrum (modern Bulgaria). The heavy limestone slab that records the inscription was excavated in the early twentieth century. It was recently restored by archaeologists led by Kalin Chakarov of the Regional Museum of History in Veliko Tarnovo, and subsequently retranslated by Nicolay Sharankov, an assistant professor in the Department of Classical Philology at Sofia University. The inscription itself is a thank-you note from the new emperor Septimius Severus. In the note Severus acknowledges receipt of a generous donation of 700,000 silver coins. As was standard practice at the time, the recipients of the letter had its contents engraved on a large slab of rock (the slab is 10 feet tall and 3 feet wide). It was then publicly displayed so that everyone could read the words of the new emperor. [Source:Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 1, 2021]

The bigger question, though, is why the city’s residents felt compelled to make such a generous donation to the emperor at all. There were empire-wide taxes, of course, but this is something different. The IRS doesn’t send us thank-you notes, nor did ancient emperors. Severus’s letter is dated to 198 CE and, according to Sharankov’s translation, states that he accepts their “cash contribution.” In lots of ways this looks like a bribe.

The context for the donation seem to have been the contest for power that consumed the last decade of the second century. The assassination of the increasingly unpredictable — some say insane — Emperor Commodus on New Year’s Eve 192 CE left a power vacuum at the heart of the empire. In the following year, five different political and military leaders competed for power. To say that things were unstable and politically dicey is an understatement. After Commodus’s death, Pertinax was named the emperor, but he rankled the Praetorian Guard (the imperial bodyguards/secret service) when he tried to initiate a program of reforms that revoked some of their privileges. Negotiations between the two failed and the Guard assassinated Pertinax and auctioned off the emperorship to the highest bidder. The winner was the somewhat unpopular Didius Julianus, but within two months he too had been killed and the general Septimius Severus assumed power. Severus swiftly dispatched his remaining rivals.

“Loyalty, or fides, was what Roman rulers most prized from people. Severus magnanimously responds that he is happy to accept the gift from those who “had taken ‘the right side’.” Like Pertinax and Didius Julianus, Septimius Severus was African. He was born in Leptis Magna in modern-day Libya to a distinguished wealthy family and rose through the political ranks to become governor of Pannonia (a Roman province that overlaps with parts of Croatia, Hungary, Austria, Slovakia, and Slovenia). After assuming power, Severus wasted no time in eliminating the competition and subduing their supporters. He first moved against those who had backed his rival Pescennius Niger. And after that he spent the following three years fighting troops loyal to Clodius Albinus. He finally emerging victorious at the battle of Lugdunum (in modern-day France) in February 197 CE and would proceed to rule for almost two decades.

Against this somewhat turbulent backdrop, it’s easy to see why the people of Nicopolis ad Istrum were eager to demonstrate their loyalty to their new ruler. But it took more than mere words to cozy up to the new dictator. Chakarov told Livescience that it is was Severus’s military success that prompted the citizens “to write a letter to the emperor, begging him for mercy, and bringing him the sum of 700,000 denarii as a gift for their loyalty.” Loyalty, or fides, was what Roman rulers most prized from people. Severus magnanimously responds that he is happy to accept the gift from those who “had taken ‘the right side’.” He even praises the people for their “zeal” and writes that they have demonstrated that they “are men of good will and loyalty and are anxious to have better standing in our judgment.”

Oratory and Politics in Ancient Rome

Oratory (public speaking) was a highly-valued skill in ancient Greece and Rome, especially for those with political ambitions. Oliver Thatcher wrote: “ ”The ordinary education of a boy was supposed to include music, gymnastics, and geometry. Under music was included Greek and Latin literature, under geometry what little was known in science. The subjects for education above what might be called the grammar school were oratory and the philosophers. A Roman's fields for action were politics and war. He learned to command in the field, and usually won the right to command through politics. The open highway through politics was oratory, and hence oratory was considered practically the only subject worthy to be the end of a youth's education.” [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

Juvenal scoffs at these would-be orators, these unmitigated asses, this Arcadian youth "who feels no flutter in his left breast when he dins his 'dire Hannibal' into my unfortunate head on every sixth day of the week," and these unhappy teachers of rhetoric who perish of "the same cabbage served up again and again." We have no need to be more Roman than the Romans and to try to whitewash a system whose frenzied pedantry the best of them have reviled.[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Young Cicero When the master of rhetoric refrained from falsifying history, he had recourse to little detective stories with too many characters and extravagant vicissitudes. His school of rhetoric knew nothing but tyrannies and conspiracies, kidnappings, reconnoitrings, obscenities, and horrors. One could hear plead there a husband who accused his wife of adultery because a rich merchant had made her his heir as a tribute to her virtue; a father who wished to disinherit his son for refusing to be seduced by the prospect of an advantageous marriage and insisting on keeping as his wife the brigand's daughter who had saved his life and helped him to regain his liberty; an impious but gallant soldier who, to arm himself for victory, had pillaged a tomb near the battlefield and robbed it of the arms that formed its trophy; a virgin whom her kidnappers had forcibly compelled to practice prostitution, but who, loathing her hideous trade, slew a ruffian who approached her, succeeded in escaping from the house of ill fame and after regaining her liberty sought an honorable post as priestess in a sanctuary.

The masters of rhetoric were proud of these imaginings. Obsessed by a desire for effect, they flattered themselves that their success varied with the improbable and complicated nature of the situations they invented and the remoteness of the characters from ordinary life. They estimated the value of an oration by the number and the gravity of the difficulties surmounted, and prized above all the eloquence which succeeded in expounding the inconceivable (materiae inopinabiles) and evolving as it were something out of nothing. Favorinus of Aries, for instance, aroused the enthusiasm of his audience one day by a eulogy of Thersites, brawler and demagogue, notorious as the ugliest man in the Greek camp before Troy, and on another occasion by an oration of thanksgiving to Quartan Fever. In short, they systematically confused artifice with art, and originality with the negation of nature; the more we reflect on their methods, the more it seems clear that they were incapable of turning out anything but parrots or third-rate play actors. It cannot be denied that people have been found, and even recently among ourselves, to take up the cudgels "to a certain extent" in their defense, speciously arguing that their pedagogy had different aims from ours and that since they sought solely to stimulate their pupils' power of invention, they had every right to imagine that the more absurd a subject was the more credit a pupil deserved for handling it. The absurdity lay in this conception itself, and such was the judgment of the last great writers of antiquity.

Quintilianus and Cicero

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus was a native of Spain. The date of his birth was about 35 A.D., of his death about 95 A.D. He began to plead causes in Spain, but after accompanying Galba to Rome where the latter was proclaimed emperor, took up pleading and the teaching of rhetoric there. To understand the position of oratory and of an instructor in it at Athens or Rome the reader must consider how little there was to learn then as compared with today. So Quintilian won honors and wealth in his profession. He was highly rewarded by Vespasian and was later the instructor of the grand-nephews of Domitian. His last years were spent in preparing his work on the education of an orator, the "Institutes."

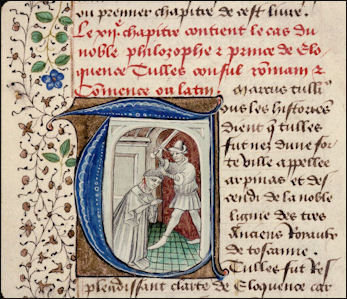

Arguably the most famous and skilled orator of all time was Cicero (106-43 B.C.), a Roman statesman, orator and writer known for his rhetorical style and eloquence. The scholar Micheal Lind wrote in the Washington Post, “No great mind in Western history “not Socrates, Plato or Aristotle — has influenced so many other great minds, Ciceronian eloquence was incorporated into Christianity by St. Augustine and St. Jerome...Machiavelli sought to revive the the republican political tradition of Cicero...The United States — more than even France — is a Ciceronian state."

Evelyn S. Shuckburgh wrote: “To his contemporaries Cicero was primarily the great forensic and political orator of his time, and the fifty-eight speeches which have come down to us bear testimony to the skill, wit, eloquence, and passion which gave him his preeminence. But these speeches of necessity deal with the minute details of the occasions which called them forth, and so require for their appreciation a full knowledge of the history, political and personal, of the time. The letters, on the other hand, are less elaborate both in style and in the handling of current events, while they serve to reveal his personality, and to throw light upon Roman life in the last days of the Republic in an extremely vivid fashion. [Source: “Letters of Marcus Tullius Cicero, with his treatises on friendship and old age; translated by E. S. Shuckburgh, New York, P. F. Collier, 1909, The Harvard classics v.9.]

RELATED ARTICLES:

CICERO (105-43 B.C.): LIFE, CAREER, WRITINGS, LEGACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO, CATO, THE CATILINE CONSPIRACY AND MEGALOPOLIS europe.factsanddetails.com

Pliny the Younger on the Decline of Oratory

As time wore on and the Roman Empire became more dictatorial and bureaucratic the skill and appreciation of it fell into decline. William Stearns Davis wrote: “As political freedom gradually ceased under the Empire, oratory was more and more confined to the courts. But, in the argument of cases, an interest was maintained that was often entirely disproportionate to the importance of the suit. Forensic oratory was practically the only public way a young man of good family could distinguish himself unless he joined the army. In the opinion of true lovers of the art, however, by 100 CE. the advocate's profession was in a very bad state, and in great danger of falling into contempt. Its evils and abuses are here explained by Pliny.”

Assassination of Cicero

Pliny the Younger (A.D. 61/62-113) wrote in “Letters, II.14": “Yes, you, Maximus [Pliny's correspondent], are quite right: my time is fully taken up by cases in the Centumviral Court, but they give me more worry than pleasure, for most of them are of a minor and unimportant nature. Most of the advocates are young men without standing, and make their first beginnings on the hardest subjects. Yet, by Heaven, before my time — to use an old man's phrase — not even the highest-born youths had any standing here, unless they were introduced by a man of consular rank. [Source: Pliny the Younger (A.D. 61/62-113): Letters, II.14: The Decline of Oratory, Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp.239-244]

“Now all modesty and respect are thrown to the winds, and one man is as good as another. So far from being introduced they burst in. The audiences follow them as if they were actors, bought and paid to do so; the agent of the orator is there to meet them in the middle of the courthouse (basilica), where the doles of money are handed over as openly as doles of food at a banquet; and they are ready to pass from one court to another for a bribe. They are made fun of for their readiness to cry "bravo"; yet this disgraceful practice gets worse every day. Yesterday two of my own nomenclators — young men I admit, about the age of those who have just assumed the toga — were enticed off to join the claque for three denarii apiece. Such is the outlay you must make to get a reputation for eloquence!

“At that price you can fill the benches, however many there are; you can obtain a great throng and get thunders of applause as soon as the conductor gives the signal. For a signal is absolutely necessary for people who do not understand, and do not even listen to the speeches; and many of these fellows do not listen at all, though they applaud as heartily as any. If you chance to be crossing the courthouse, and wish to know how any one is speaking, there is no need to stop to listen. It is quite safe to guess on the principle that he who is speaking worst gets the most applause. The sing-song style of this clique only wants the clapping of hands, or rather cymbals and drums, to make them like the priests of Cybele, for as for howlings — that is the only word to express the unseemly applause — they have enough and to spare.”

Patronage and Promotion in Vindolanda

The Roman-era Vindolanda tablets — found at a fort near Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britain — are the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain. Based on texts found on these tablets, Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “Flavius Cerialis was the praefectus in command of Cohors IX Batavorum, which occupied Vindolanda from around A.D. 97 onwards. His name indicates that his family was granted the citizenship by the Flavian dynasty of Vespasian, and the cognomen Cerialis may have been in honour of Q. Petilius Cerialis, who brought the Batavians over to Britain. He was a Batavian nobleman of equestrian status, which meant that his family had amassed a fortune of over 400,000 sesterces (100,000 denarii), the property qualification for entry into the equestrian order.” [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, November 16, 2012 |::|]

“He was therefore, an important man in the area, and it was only natural for those who knew him to request letters of recommendation for their friends. One of these survives, from a certain Claudius Karus. (Tab. Vindol. II.250): ‘Brigionus has requested me, my lord, to recommend him to you. I therefore ask, my lord, if you would be willing to support him. I ask that you think fit to commend him to Annius Equester, the centurion in charge of the region at Luguvalium, by doing which you will place me in debt to you, both in his name and my own’.

“Brigionus is a Romanised Celtic name, and it does not take a great leap of imagination to see this as a classic example of patronage, by which the subjects of the frontier region were absorbed into the Roman system. Karus, a fellow officer, recommends to Cerialis a British client, and requests that he pass him on in turn to the regional administration officer for the legions, Annius Equester, whether as a potential recruit or for some other purpose is not clear (though given that it is being done through military channels, I would suspect the former). |::|

“Cerialis clearly had good contacts of his own, with which he was trying to wangle a promotion. Here are a couple of letters that paint an interesting little picture: ‘[Cerialis ] to his Crispinus... Since Grattius Crispinus is returning to [you], I have gladly seized this opportunity, my lord, of greeting you, whom I dearly wish to be in good health and master of all your hopes. For you have always deserved this of me, right up to your present high office... greet Marcellus, that most distinguished man, my governor. He offers opportunity for the talents of your friends, now that he is here, for which I know you thank him. Now, in whatever way you wish, fulfil what I expect of you and... so furnish me with very many friends, so that thanks to you I may be able to enjoy an agreeable period of military service. I write this to you from Vindolanda, where my winter quarters are’. (Tab. Vindol. II.225)

‘Niger & Brocchus to their Cerialis, greeting. We pray, brother, that what you are about to do is most successful. It will be so indeed, since our prayers are with you and you yourself are most worthy. You will assuredly meet our governor quite soon.’ (Tab. Vindol. II.248) |::|

“We do not know who Crispinus is, but he was clearly a high-ranking official in the province, with the ear of the provincial governor, L. Neratius Marcellus (Leg. Brit. A.D. 100-103). Cerialis obviously hoped by his patronage to gain a promotion from the governor, and his friends and fellow officers, Niger & Brocchus, clearly wished him well. The somewhat tart: 'I write this to you from winter quarters in Vindolanda.' might give some indication of how Cerialis viewed life up on the cold north-west frontier, as does another letter to a fellow officer, an aptly named September, offering to send him some goods: 'by which we may endure the storms, even if they are troublesome.' “ |::|

“We do not know whether Cerialis was successful in pursuing his promotion, but we do know about his friend. C. Aelius Brocchus went on to command the prestigious Ala Contariorum in Pannonia. At times, official channels could be abused, or at least stretched, in order to accommodate those in the position to take advantage of them. A legionary centurion called Clodius Super asks Cerialis to send him some clothing Cerialis had picked up from a friend in Gaul, saying: 'I am the supply officer, so I have acquired transport'. (Tab. Vindol. II.255).

Proceedings at the Senate in the Roman Empire

Cato Minor

another prominent politician Since the days of Augustus the number of ordinary sessions of the Senate (dies legitimi) had been greatly reduced. The months of September and October were decreed to be a compulsory vacation; during the rest of the year the Senate was normally convoked only twice a month on the Calends and the Ides; and the legislative activity of the Caesars left the law-making functions of the Senate to lie dormant. But from time to time the Senate had to reckon with extraordinary sessions, all the more overladen with business for being infrequent, especially such as compelled or permitted the princeps to perform terrible acts of vengeance for political crimes, for which he preferred nominally to evade responsibility. At such moments the Fathers were condemned, to forced labour, and they had no means of escaping the slavery of these sensational convocations unless they could find some pretext for absence that would be accepted as valid and would not cast doubt on their motives for abstention. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The Senate assembled in the Curia of Julius Caesar. Its reconstruction under Diocletian has in all probability preserved the original plan and dimensions. It measured 25.5 meters in length and 67.6 in width. It could scarcely have provided space for more than 300 seats distributed in three rising tiers, as Professor Bartoli has recently discovered by his excavations beneath the floor of the ancient church of Sant' Adriano. On great occasions, when at least one-third of the total 900 members of the Senate responded to the summons, they must have been as tightly packed as the English Parliament in the House of Lords when the Commons attend to hear the Speech from the Throne. After a sacrifice and preliminary prayers, the senators entered the Curia at the first hour of the day, and did not escape till night was falling. They sat again next day, and the day after, and the day after that again, and for several days more. They could not possibly have endured this penitential overcrowding if the rules of the assembly, or rather the customary practice which served instead, had not implicitly permitted them to come and go, vanish and reappear at will. In the hall there was an endless series of discussions, a continual deluge of eloquence and knavery.

Pliny the Younger gives accounts of several sessions of the Senate transformed into a High Court: those where Marius Priscus, proconsul of Africa, appeared with his rivals in the art of prevarication; those which investigated and punished the extortions of Caecilius Classicus, ex-governor of Baetica. These reports call forth our pity for the senator chained to his curule chair. The first of these cases, over which Trajan presided in his capacity of consul, lasted from dawn to dusk through three consecutive days. On one of them Pliny the Younger, who had been entrusted with the prosecution of one of Priscus' accomplices, spoke for five hours without intermission, and toward the close his fatigue became so manifest that the emperor sent him more than once the advice "to spare his voice and breath." When he had finished, Claudius Marcellinus replied for the accused in a speech of the same length. When this second orator had reached his peroration Trajan adjourned the court till next day for fear a third harangue "might be cut in two by nightfall."

In comparison with the impeachment of Priscus the case of Classicus, in which Pliny's role was confined to listening and offering an opinion, appeared much easier to endure and seemed really "short and easy: et circa Classicum quidem brevis et expeditus labor." Easy it certainly was, for the Spaniards had broken the back of the business for the prosecution, and mined in advance all the positions of the defense by laying hands on the intimate and cynical correspondence of the accused; in particular on a letter in which, blending his. love affairs and his extortions, he announced his return to Rome to one of his mistresses in terms which inculpated him beyond hope of salvation: "Hurrah I Hurrah 1 I am coming back to you a free man, for I have raised four million sesterces by selling out the Baetici." But short the Classicus case certainly was not, despite the overwhelming nature of the facts established by this damning evidence. Like the Priscus case it took up three sessions of the Senate, and though Pliny the Younger had played a less spectacular part in it, he came out exhausted, when it was over, just as after the Priscus affair: "You will easily conceive," he writes to his dear friend Cornelius Minicianus, "... the fatigue we underwent in speaking and debating so long and so often, and in examining, assisting, and confuting such a number of witnesses; not to mention the difficulties and annoyance of the defendants' friends: Concipere animo poles quam simus fatigati!" We can indeed conceive it, but what seems inconceivable to us is that the Romans should have tolerated this exhausting system with no attempt to modify or lighten it. Are we to believe that their heads and nerves were more resistant to strain than ours? Or that, having been inured by a century of public readings, they had become case-hardened against exasperation, weariness, and boredom?

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024