Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.) / Government and Justice

ROMAN REPUBLIC GOVERNMENT

On the local level Roman administration was "flexible, tolerant and open." Most towns elected a “ duumvir” (mayor) and “ aedilis” (commissioner of markets). Public servants wore blue, which some scholars say set the precedent for the blue uniforms used by policeman. During the third and fourth centuries B.C. politics was a gentlemanly affair. There were also people's assemblies that passed legislation and administered jurisdictions. Later these popular assemblies "fell into disuse" and power was centered in the Senate. [Source: Lionel Casson, Smithsonian]

The Romans never had a written constitution, but their form of their government, especially from the time of the passage of the lex Hortensia (287 B.C.), roughly parallels the modern American division of executive, legislative, and judical branches, although the senate doesn't neatly fit any of these categories. What follows is a fairly traditional, Mommsenian reconstruction, though at this level of detail most of the facts (if not the significance of, e.g., the patrician/plebian distinction) are not too controversial. One should be aware, however, of the difficulties surrounding the understanding of forms of government (as well as most other issues) during the first two centuries of the Republic. [For a mid-second century B.C. outsider's account of the Roman government see John Porter's translation of Polybius 6.11-18.] [Source: University of Texas at Austin ==]

Criminal prosecution: originally major crimes against the state tried before centuriate assembly, but by late Republic (after Sulla) most cases prosecuted before one of the quaestiones perpetuae ("standing jury courts"), each with a specific jurisdiction, e.g., treason (maiestas), electoral corruption (ambitus), extortion in the provinces (repetundae), embezzlement of public funds, murder and poisoning, forgery, violence (vis), etc. Juries were large (c. 50-75 members), composed of senators and (after the tribunate of C. Gracchus in 122) knights, and were empanelled from an annual list of eligible jurors (briefly restricted to the senate again by Sulla).

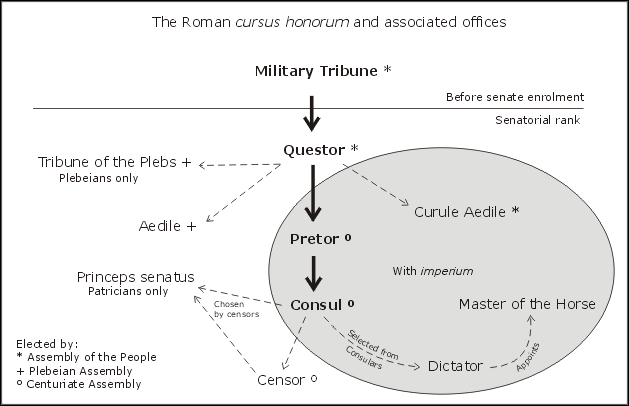

Rome started off led by kings. It transformed into a republic in 509 B.C. Early on, prominent, wealthy families (patricians) made up those represented by the established senate, which upheld the interests of the upper class. However, after lower-class citizens (plebeians) protested — many of whom were Roman soldiers — the senate expanded government to include other assemblies that could draft laws for them to implement. The first plebeian consul was in 366 B.C., the first plebeian dictator was in 356 B.C. , the first plebeian censor was in 351 B.C. and first plebeian praetor was in 336 B.C.. The many priestly colleges (flamines, augures, pontifex maximus, etc.) were also state offices, held mostly by patricians. Imperium is the power of magistrates to command armies and (within limits) to coerce citizens. [Source: BuzzFeed, September 20, 2023; ==]

RELATED ARTICLES:

CITIZENS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN EMPIRE: SIZE, GOVERNMENT, ADMINISTRATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STRUCTURE OF THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT: BRANCHES, CONSULS, SENATE, ASSEMBLIES, COMITIA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FALL OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC AND RISE OF IMPERIAL ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EVOLUTION OF ROMAN GOVERNMENT AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO (105-43 B.C.): LIFE, CAREER, WRITINGS, LEGACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POLITICS IN ANCIENT ROME: CAMPAIGNS, PATRONAGE, CORRUPTION AND ORATORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PROPAGANDA IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY ROMAN REPUBLIC: ITS FOUNDING, DEVELOPMENT AND EXPANSION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LAST THREE KINGS OF EARLY ROME: LEGENDS, ETRUSCAN ORIGINS, VIOLENCE, UPHEAVAL europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PLEBEIANS AND PATRICIAN IN THE EARLY ROMAN REPUBLIC europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FALL OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC AND RISE OF IMPERIAL ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“On Government” (Penguin Classics) by Marcus Tullius Cicero, translated by Michael Grant (1994)

“Rome: The Center of Power, 500 B.C. to A.D. 200" by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, translated by Peter Green Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome: Infographics” by Nicolas Guillerat, John Scheid (2021) Amazon.com;

“Democracy: A Life” by Paul Cartledge (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The Thirty-five Urban and Rural Tribes”

by Lily Ross Taylor and Jerzy Linderski (2013) Amazon.com;

“Power and Public Finance at Rome, 264-49 BCE” by James Tan (2017) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“The Republic and The Laws” (Oxford World's Classics) by Cicero Amazon.com;

“The Constitution of the Roman Republic” by Andrew Lintott Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Tables” Amazon.com;

“Patricians and Plebeians: The Origin of the Roman State” by Richard E. Mitchell (1990) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“The Roman Republic” by Isaac Asimov (1966) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic” by P. A. Brunt Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome From Romulus to Augustus” by Philip Matyszak Amazon.com;

“Roman Republics” by Harriet I. Flower (2009) Amazon.com

“A History of the Roman Republic” by Cyril E. Robinson (2013) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Roman Republic 264–30 BC: History, Organization and Equipment

by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome” by Nigel Rodgers, Illustrated History (2006) Amazon.com

Sovereign Roman State

To understand properly the history of Rome, we must study not only the way in which she conquered her territory, but also the way in which she organized and governed it. The study of her wars and battles is less important than the study of her policy. Rome was always learning lessons in the art of government. As she grew in power, she also grew in political wisdom. With every extension of her territory, she was obliged to extend her authority as a sovereign power. If we would comprehend the political system which grew up in Italy, we must keep clearly in mind the distinction between the people who made up the sovereign body of the state, and the people who made up the subject communities of Italy. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Roman republic flag

"Just as in early times we saw two distinct bodies, the patrician body, which ruled the state, and the plebeian body, which was subject to the state; so now we shall see, on the one hand, a ruling body of citizens, who lived in and outside the city upon the Roman domain (ager Romanus), and on the other hand, a subject body of people, living in towns and cities throughout the rest of Italy. In other words, we shall see a part of the territory and people incorporated into the state, and another part unincorporated—the one a sovereign community, and the other comprising a number of subject communities.

The Roman domain proper, or the ager Romanus, was that part of the territory in which the people became incorporated into the state, and were admitted to the rights of citizenship. It was the sovereign domain of the Roman people. This domain land, or incorporated territory, had been gradually growing while the conquest of Italy was going on. It now included, speaking generally, the most of Latium, northern Campania, southern Etruria, the Sabine country, Picenum, and a part of Umbria. There were a few towns within this area, like Tibur and Praeneste, which were not incorporated, and hence not a part of the domain land, but retained the position of subject allies. \~\

The Thirty-three Tribes: Within the Roman domain were the local tribes, which had now increased in number to thirty-three. They included four urban tribes, that is, the wards of the city, and twenty-nine rural tribes, which were like townships in the country. All the persons who lived in these tribal districts and were enrolled, formed a part of the sovereign body of the Roman people, that is, they had a share in the government, in making the laws, and in electing the magistrates. \~\

Roman Colonies and Subject Communities

The colonies of citizens sent out by Rome were allowed to retain all their rights of citizenship, being permitted even to come to Rome at any time to vote and help make the laws. These colonies of Roman citizens thus formed a part of the sovereign state; and their territory, wherever it might be situated, was regarded as a part of the ager Romanus. Such were the colonies along the seacoast, the most important of which were situated on the shores of Latium and of adjoining lands. \~\

The Roman Municipia: Rome incorporated into her territory some of the conquered towns under the name of municipia, which possessed all the burdens and some of the rights of citizenship. At first, such towns (like Caere) received the private but not the public rights (civitas sine suffragio),—see page 64,—and the towns might govern themselves or be governed by a prefect sent from Rome. In time, however, the municipia obtained not only local self-government but also full Roman citizenship; and this arrangement was the basis of the Roman municipal system of later times. \~\

The Subject Territory: Over against this sovereign body of citizens living upon the ager Romanus, were the subject communities scattered throughout the length and breadth of the peninsula. The inhabitants of this territory had no share in the Roman government. Neither could they declare war, make peace, form alliances, or coin money, without the consent of Rome. Although they might have many privileges given to them, and might govern themselves in their own cities, they formed no part of the sovereign body of the Roman people. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The Latin Colonies: One part of the subject communities of Italy comprised the Latin colonies. These were the military garrisons which Rome sent out to hold in subjection a conquered city or territory. They were generally made up of veteran soldiers, or sometimes of poor Roman citizens, who were placed upon the conquered land and who ruled the conquered people. But such garrisons did not retain the full rights of citizens. They lost the political rights, and generally the conubium (p. 64), but retained the commercium. These colonies, scattered as they were throughout Italy, carried with them the Latin language and the Roman spirit, and thus aided in extending the influence of Rome. \~\

The Italian Allies: The largest part of the subject communities were the Italian cities which were conquered and left free to govern themselves, but which were bound to Rome by a special treaty. They were obliged to recognize the sovereign power of Rome. They were not subject to the land tax which fell upon Roman citizens, but were obliged to furnish troops for the Roman army in times of war. These cities of Italy, thus held in subjection to Rome by a special treaty, were known as federated cities (civitates foederatae), or simply as allies (socii); they formed the most important part of the Italian population not incorporated into the Roman state. \~\

This method of governing Italy was, in some respects, based upon the policy which had formerly been adopted for the government of Latium. The important distinction between Romans, Latins, and Italians continued until the “social war”. \~\

Map of Italy when Rome was emerging as a state

Strengths of the Roman System

Edward Gibbon wrote in “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: “The Greeks, after their country had been reduced into a province, imputed the triumphs of Rome, not to the merit, but to the fortune, of the republic. The inconstant goddess, who so blindly distributes and resumes her favours, had now consented (such was the language of envious flattery) to resign her wings, to descend from her globe, and to fix her firm and immutable throne on the banks of the Tiber. A wiser Greek, who has composed, with a philosophic spirit, the memorable history of his own times, deprived his countrymen of this vain and delusive comfort by opening to their view the deep foundations of the greatness of Rome. [Source: Edward Gibbon: General Observations on the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West from “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Chapter 38, published 1776]

“The fidelity of the citizens to each other, and to the state, was confirmed by the habits of education and the prejudices of religion. Honour, as well as virtue, was the principle of the republic; the ambitious citizens laboured to deserve the solemn glories of a triumph; and the ardour of the Roman youth was kindled into active emulation, as often as they beheld the domestic images of their ancestors. The temperate struggles of the patricians and plebeians had finally established the firm and equal balance of the constitution; which united the freedom of popular assemblies with the authority and wisdom of a senate-and the executive powers of a regal magistrate. When the consul displayed the standard of the republic, each citizen bound himself, by the obligation of an oath, to draw his sword in the cause of his country, till he had discharged the sacred duty by a military service of ten years.

“This wise institution continually poured into the field the rising generations of freemen and soldiers; and their numbers were reinforced by the warlike and populous states of Italy, who, after a brave resistance, had yielded to the valour, and embraced the alliance, of the Romans. The sage historian, who excited the virtue of the younger Scipio and beheld the ruin of Carthage,has accurately described their military system; their levies, arms, exercises, subordination, marches, encampments; and the invincible legion, superior in active strength to the Macedonian phalanx of Philip and Alexander. From these institutions of peace and war, Polybius has deduced the spirit and success of a people incapable of fear and impatient of repose. The ambitious design of conquest, which might have been defeated by the seasonable conspiracy of mankind, was attempted and achieved; and the perpetual violation of justice was maintained by the political virtues of prudence and courage. The arms of the republic, sometimes vanquished in battle, always victorious in war, advanced with rapid steps to the Euphrates, the Danube, the Rhine, and the Ocean; and the images of gold, or silver, or brass, that might serve to represent the nations and their kings, were successively broken by the iron monarchy of Rome.”

Roman Influence on the Fledgling American Government

According to the Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments: The Roman model of republicanism had far-reaching influence on political thinking in succeeding centuries, from Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) of the Italian Renaissance, to the philosophers of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century, to the founding fathers of the United States of America. These thinkers held up the Roman Republic as an ideal to be re-created and sought to understand how a modern republic could avoid the collapse that befell the Romans. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Encyclopedia.com]

The American founding fathers emulated the Rome. The seat of the government was in the "capitol" — a term of Roman derivation — and the government itself had two legislatures (a House of representatives and a Senate) just like the one in Republican Rome. The word “Senate” also comes from Rome. Cicero was the first one who came with idea of checks and balances — an ideal central to the American form of government.

Roman Republican government

After the Boston massacre a patriot stood on Bunker Hill in a toga and gave a speech in the "manner of Cicero" and during the winter at Valley Forge, George Washington tried to cheer up his troop with a "play about the Roman's senate's fatal last stand" against Caesar. Statues of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and other influential American leaders were made with their subjects dressed in togas and sandals. [Source: “The Founders and the Classics” by Carl Richard (1994)]

The English historian Ronald Syme has argued that if the George III had used Roman colonization as his model and shown more tolerance and incorporated the likes of Washington, Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson into the local government then the American Revolution could have been avoided.

On the Precepts of Statecraft, Plurach wrote: “The greatest blessings that cities can enjoy are peace, prosperity, populousness, and concord. As far as peace is concerned the people have no need of political activity, for all war, both Greek and foreign, has been banished and has disappeared from among us. Of liberty the people enjoy as much as our rulers allot them, and perhaps more would not be better. A bounteous productiveness of soil; a mild, temperate climate; wives bearing "children like to their sires," and security for the offspring-these are the things that the wise man will ask for his fellow citizens in his prayers to the gods.”

Roman Versus American Government: Checks and Balances

Richard Saller, a Professor of Classics and History at Stanford University, told National Geographic that he skeptical about parallels between the governments of ancient Rome and thos of the modern United States. “The constitutional situation in the U.S. and Rome are very, very different. One of the things that Rome did not have was anything like our Supreme Court. Whatever problems we may think we have with our current Supreme Court, the Roman Republic had no institutional way of resolving differences between leading senatorial generals in their contest for power.” [Source Gregory Wakeman, National Geographic History, September 27, 2024]

American System — based on balance of powers/functions: ; 1) Executive; 2) Legislative; 3) Judicial; 4) President; 5) Congress; 6) Supreme Court; 7) Note: The only legitimate interest is that of the people [Source: by Paul Halsall]

Roman System — based on balance of interests; 1) Monarchical; 2) Aristocratic; 3) Democratic; 4) 2 Consuls + other magistrates; 5) Senate; 6) Assembly of Tribes; 7) Tribune; 8) Directed government and army; 9) Acted as judges; 10) Could issue edicts; 12) Acted as chief priest; 13) Controlled state budget; 14) Could pass laws; 15) Approved/rejected laws; 16) Decided on War; 17) Tribune could veto actions of magistrate; 18 ) Acted as final court

Basis of power — Roman System; 1) possess imperium, the right to rule; 2) need for leadership; 3) members were richest men in Rome; 4) provided most of the soldiers

Limits on power — Roman System; 1) one year term; 2) each could veto; 3) could not control army; 4) needed majority as soldiers; 5) Could not suggest laws; 6) often paid as clients by the elite

Concepts of Fides and Virtus

On the Roman concept of fides, which is sort of like Roman filial piety, John Paul Adams of CSUN wrote: “"FIDES" is often (and wrongly) translated 'faith', but it has nothing to do with the word as used by Christians writing in Latin about the Christian virute (St. Paul Letter to the Corinthians, chapter 13). For the Romans, FIDES was an essential element in the character of a man of public affairs, and a necessary constituent element of all social and political transactions (perhaps = 'good faith'). FIDES meant 'reliablilty', a sense of trust between two parties if a relationship between them was to exist. FIDES was always reciprocal and mutual, and implied both privileges and responsibilities on both sides. In both public and private life the violation of FIDES was considered a serious matter, with both legal and religious consequences. FIDES, in fact, was one of the first of the 'virtues' to be considered an actual divinity at Rome. The Romans had a saying, "Punica fides" (the reliability of a Carthaginian) which for them represented the highest degree of treachery: the word of a Carthaginian (like Hannibal) was not to be trusted, nor could a Carthaginian be relied on to maintain his political elationships. [Source: John Paul Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), May 24, 2009]

“Some relationships governed by fides, with one member mutually related to other member: 1)Amicus (friend) — Amicus (friend); 2) Pater (father) — Familia (household); 3) Pater (father)— Filius (son); 4) Dominus (master) — Servus (slave); 5) Patronus (patron) — Libertus (freedman); 6) Patronus (patron) — Cliens (client); 7) Respublica (the Roman State) — Socius (an ally of Rome).

Roman Republican government versus US government

“VIRTUS, for the Roman, does not carry the same overtones as the Christian 'virtue'. But like the Greek andreia, VIRTUS has a primary meaning of 'acting like a man' (vir) [cf. the Renaissance virtù ), and for the Romans this meant first and foremost 'acting like a brave man in military matters'. virtus was to be found in the context of 'outstanding deeds' (egregia facinora), and brave deeds were the accomplishments which brought GLORIA ('a reputation'). This GLORIA was attached to two ideas: FAMA ('what people think of you') and dignitas ('one's standing in the community'). The struggle for VIRTUS at Rome was above all a struggle for public office (honos), since it was through high office, to which one was elected by the People, that a man could best show hi smanliness which led to military achievement--which would lead in turn to a reputation and votes. It was the duty of every aristocrat (and would-be aristocrat) to maintain the dignitas which his family had already achieved and to extend it to the greatest possible degree (through higher political office and military victories). This system resulted in a strong built-in impetus in Roman society to engage in military expansion and conquest at all times.

Categories of 'Virtues' of a Statesman according to Augustus; 1) knowing what is appropriate 2) wisdom; 3) prudence; 4) fortitudo; 5) virtus; 6) ability to convince; 7) andreia; 8) bravery; 9) clementia; 10) incorruptibility; 11) justice; 12) justitia; 13) patriotism; 14) piety; 16 ) self-restraint; 17 ) benignitas; 18) pietas

Changing Views of the Roman Model

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill of the University of Reading wrote for the BBC: “A gap of 2,000 years may seem to have put the Romans at a safe distance from our own lives and experience, but modern Europe with its Union is unthinkable without the Roman Empire. It is part of the story of how we came to be what we are. |The Romans are important as a conscious model, for good or ill, to successive generations. Why do they have such a powerful hold on our imaginations? What attracts us to them, or repulses us? What do they have in common with us, and what makes them different? [Source: Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“A century ago, for imperialist Britain (and for other European states with imperial ambitions), the Roman Empire represented a success story. Rome's story of conquest, at least in Europe and around the Mediterranean, was imitated, but never matched, by leaders from Charlemagne to Napoleon. The dream that one could not only conquer, but in so doing create a Pax Romana, a vast area of peace, prosperity and unity of ideas, was a genuine inspiration. |::|

“But the efforts of 20th-century dictators such as Mussolini, peculiarly obsessed with the dream of reviving an empire centred on Rome, left Europe disillusioned with the Roman model. The dream of peace, prosperity and unity survives, but Roman style conquest now seems not the solution but the problem. Centralised control, the suppression of local identities, the imposition of a unified system of beliefs and values - let alone the enslavement of conquered populations, the attribution of sub-human status to a large part of the workforce, and the deprivation of women of political power - all now spell for us not a dream but a nightmare. |::|

Ancient Roman Citizens

Roman military diploma

granting citizenship Government officials were elected by Roman, citizens Citizens could vote; had rights and responsibilities under a "well administered system of criminal and civil law. Men of both the upper and lower classes could be citizens. Women and slaves were not allowed to be citizens

Citizenship was generally passed down from father to son. The easiest way for non-citizens to become citizens was join the military. After being discharged for 20 years of service soldiers became citizens. The completion of military service provided citizenship not only to the soldier but to his entire family. Even barbarians were recruited with these promises.

Any male regarded as worthy, regardless of ethnic background, could become a Roman citizen. “E Pluibus Unum” , the words featured on all American coins, meant that on any position in the empire was open to suitable candidates regardless of ethnic group or background. Within a fairly short time, the conquered people were made citizens of Rome and given all the rights and privileges that status entailed. Septimius Severus, a North African general became emperor of Rome and served for 18 years. Trajan, one of Rome's greatest emperors was from Spain.

Political Parties and Factions in the Roman Republic

Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Rome was traditionally divided between two social orders: the patricians, landed aristocrats of wealthy families who controlled the government, and the plebeians, ordinary citizens, often poor farmers, who made up most the population. Throughout its history, the Roman Republic experienced conflict between these two classes, referred to as the “struggle of orders.” In the years leading up to the Roman civil wars, a new social order emerged, the equestrians (or equites), who had profited from manufacturing and trade and exploited the newly conquered territories for financial gain. This class would figure prominently in later centuries under the Roman Empire.[Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Encyclopedia.com]

During the late Republic (133–27 B.C.) two distinct political factions formed: the optimates (best of men) and the populares (populists). Members of both groups belonged to the patrician class. The optimates were senatorial conservatives who sought to uphold the traditional power of the aristocracy by limiting the power of the popular assemblies, enlarging the role of the Senate, and defining citizenship narrowly. By contrast, the populares favored land and wealth redistribution, encouraged a broad definition of Roman citizenship to include people in the provinces, and aimed to deprive the Senate of its political stranglehold.

Heyday of the Roman Senate

Starting in the third century B.C., the Senate was the most powerful political body in Rome and it stayed that way for 150 years until Caesar seized control in 48 B.C. and established himself as a dictatorial emperor, a trend that continued until Rome fell. The Senate consisted of hundreds of members who served for life. It was sort of like the House of Lords in the British Parliament and senators were required by law to have a large fortune. "Not unexpectedly," wrote historian Lionel Casson, "they traditionally came from a circumscribed number of famous old families. For centuries this narrow circle of wealthy aristocrats was the establishment, Elections simply determined which among them would fill the higher offices and whose sons would get the lower."

Roman senators

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “To the senate belongs, in the first place, the sole care and management of the public money. For all returns that are brought into the treasury, as well as all the payments that are issued from it, are directed by their orders. Nor is it allowed to the quaestors to apply any part of the revenue to particular occasions as they arise, without a decree of the senate; those sums alone excepted. which are expended in the service of the consuls. And even those more general, as well as greatest disbursements, which are employed at the return every five years, in building and repairing the public edifices, are assigned to the censors for that purpose, by the express permission of the senate. To the senate also is referred the cognizance of all the crimes, committed in any part of Italy, that demand a public examination and inquiry: such as treasons, conspiracies, poisonings, and assassinations. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“Add to this, that when any controversies arise, either between private men, or any of the cities of Italy, it is the part of the senate to adjust all disputes; to censure those that are deserving of blame: and to yield assistance to those who stand in need of protection and defense. When any embassies are sent out of Italy; either to reconcile contending states; to offer exhortations and advice; or even, as it sometimes happens, to impose commands; to propose conditions of a treaty; or to make a denunciation of war; the care and conduct of all these transactions is entrusted wholly to the senate. When any ambassadors also arrive in Rome, it is the senate likewise that determines how they shall be received and treated, and what answer shall be given to their demands.”

Introduction of Secret Ballots to Ancient Rome

The ballot laws of the Roman Republic (Latin: leges tabellariae) were four laws which introduced the secret ballot to all popular assemblies in the Republic. They were all introduced by tribunes, and consisted of the lex Gabinia tabellaria (or lex Gabinia) of 139 B.C., applying to the election of magistrates; the lex Cassia tabellaria of 137 B.C., applying to juries except in cases of treason; the lex Papiria of 131 B.C., applying to the passing of laws; and the lex Caelia of 107 B.C., which expanded the lex Cassia to include matters of treason. [Source Wikipedia]

Prior to the ballot laws, voters announced their votes orally to a teller, essentially making every vote public. The ballot laws curtailed the influence of the aristocratic class and expanded the freedom of choice for voters. Elections became more competitive. In addition, the secret ballot made bribery more difficult.

The 130s and 120s B.C. were a turning point for Roman politics. The ballot laws were introduced at a time of rising popular sentiment that saw the rise of populist politicians (populares), who gained power by appealing to the lower classes. The most well-known of these were Tiberius Gracchus in 133 B.C. and Gaius Gracchus a decade later. The resulting conflict between populares (who operated mostly in popular assemblies) into and optimates (who operated mostly in the Senate) lead to the dissolution of political norms and the rise of political violence. Within decades, mob violence, political assassination, and even civil war would become routine. These conflicts would cause the end of the republic in 27 B.C.

Power of the People Over the Senate in the 2nd Century B.C.

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “In the same manner the senate also, though invested with so great authority, is bound to yield a certain attention to the people, and to act in concert with them in all affairs that are of great importance. With regard especially to those offences that are committed against the state, and which demand a capital punishment, no inquiry can be perfected, nor any judgment carried into execution, unless the people confirm what the senate has before decreed. Nor are the things which more immediately regard the senate itself less subject than the same control. For if a law should at any time be proposed to lessen the received authority of the senators, to detract from their honors and pre-eminence, or even deprive them of a part of their possessions, it belongs wholly to the people to establish or reject it. And even still more, the interposition of a single tribune is sufficient, not only to suspend the deliberations of the senate, but to prevent them also from holding any meeting or assembly. Now the peculiar office of the tribunes is to declare those sentiments that are most pleasing to the people: and principally to promote their interests and designs. And thus the senate, on account of all these reasons, is forced to cultivate the favor and gratify the inclinations of the people. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

Cursus

“The people again, on their part, are held in dependence on the senate, both to the particular members, and to the general body. In every part of Italy there are works of various kinds, which are let to farm by the censors, such are the building or repairing of the public edifices, which are almost innumerable; the care of rivers, harbors, mines and lands; every thing, in a word, that falls beneath the dominion of the Romans. In all these things the people are the undertakers: inasmuch as there are scarcely any to be found that are not in some way involved, either in the contracts, or in the management of the works. For some take the farms of the censors at a certain price; others become partners with the first. Some, again, engage themselves as sureties for the farmers; and others, in support also of these sureties, pledge their own fortunes to the state. Now, the supreme direction of all these affairs is placed wholly in the senate.

“The senate has the power to allot a longer time, to lighten the conditions of the agreement, in case that any accident has intervened, or even to release the contractors from their bargain, if the terms should be found impracticable. There are also many other circumstances in which those that are engaged in any of the public works may be either greatly injured or greatly benefited by the senate; since to this body, as we have already observed, all things that belong to these transactions are constantly referred. But there is still another advantage of much greater moment. For from this order, likewise, judges are selected, in almost every accusation of considerable weight, whether it be of a public or private nature. The people, therefore, being by these means held under due subjection and restraint, and doubtful of obtaining that protection, which they foresee that they may at some time want, are always cautious of exciting any opposition to the measures of the senate. Nor are they, on the other hand, less ready to pay obedience to the orders of the consuls; through the dread of that supreme authority, to which the citizens in general, as well as each particular man, are obnoxious in the field.”

What Can Bring a Government Down

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “Now there are two ways by which every kind of government is destroyed; either by some accident that happens from without, or some evil that arises within itself. What the first will be is not always easy to foresee: but the latter is certain and determinate. We have already shown what are the original and what: the secondary forms of government; and in what manner also they are reciprocally converted each into the other. Whoever, therefore, is able to connect the beginning with the end in this enquiry, will be able also to declare with some assurance what will be the future fortune of the Roman government. At least in my judgment nothing is more easy. For when a state, after having passed with safety through many and great dangers, arrives at the highest degree of power, and possesses an entire and undisputed sovereignty; it is manifest that the long continuance of prosperity must give birth to costly and luxurious manners, and that the minds of men will be heated with ambitious contest, and become too eager and aspiring in the pursuit of dignities. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“And as these evils are continually increased, the desire of power and rule, and the imagined ignominy of remaining in a subject state, will first begin to work the ruin of the republic; arrogance and luxury will afterwards advance it: and in the end the change will be completed by the people; as the avarice of some is found to injure and oppress them, and the ambition of others swells their vanity and poisons them with flattering hopes. For then, being with rage, and following only the dictates of their passions, they no longer will submit to any control, or be contented with an equal share of the administration, in conjunction with their rulers; but will draw to themselves the entire sovereignty and supreme direction of all affairs. When this is done, the government will assume indeed the fairest of all names, that of a free and popular state; but will, in truth, be the greatest of all evils, the government of the multitude.

“As we have thus sufficiently explained the constitution and the growth of the Roman government; have marked the causes of that greatness in which it now subsists; and shown by comparison, in what view it may be judged inferior, and in what superior, to other states; we shall here close this discourse. But as every skillful artist offers some piece of work to public view, as a proof of his abilities: in the same manner we also, taking some part of history that is connected with the times from which we were led into this digression and making a short recital of one single action, shall endeavor to demonstrate by fact as well as words what was the strength, and how great the vigor, which at that time were displayed by this republic.”

Decline of the Roman Senate and the End of the Republic

In 133 B.C., and the years that followed," Casson wrote, "the situation changed radically. First reformers broke away from the Establishment. Then ambitious figures from outside it...made their way into politics by getting the rank and fill behind them. Reformers and new men not only entered contests for higher office, but succeeded in bypassing the Senate by resuscitating the long-dormant people's assemblies. [Source: Lionel Casson , Smithsonian magazine]

The original republican government with democratic features added in 4th and 5th centuries B.C. slowly disappeared as a strong central government was needed to maintain order in the face of class conflict, slave revolts (135, 75), murders, assassinations, social reforms, and civil war (Caesar vs. Pompey, Caesar’s assassins vs. triumvirates, Octavian vs. Antony).

The Roman Republic began the process of coming to an ended when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 B.C. and began the process of becoming the leader of Rome. After Julius Caesar finished subduing Gaul in 51 B.C., he defied the Republican tradition of victorious Roman generals not being allowed to return to Rome with their armies out of fear they would try to overthrow the government, which is exactly what Caesar did. By crossing the Rubicon Caesar declared war on the political establishment of his day. For many historians it marked the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire. To this day “crossing the Rubicon” describes a decision from which there is no return.

The Roman Republic officially ended in 27 B.C. with the establishment of the Roman Empire following the War of Actium. After Caesar was assassinated in in 44 B.C. his heir Octavian and Mark Antony defeated Caesar's assassins in 42 B.C,, but they eventually split. After the defeat of Antony and his ally and lover Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C., and the Senate granted extraordinary powers to Octavian as Augustus in 27 B.C. — which effectively made him the first Roman emperor—marked the end of the Republic.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024