Home | Category: Age of Augustus

ANTONY (OCTAVIAN) AND CLEOPATRA

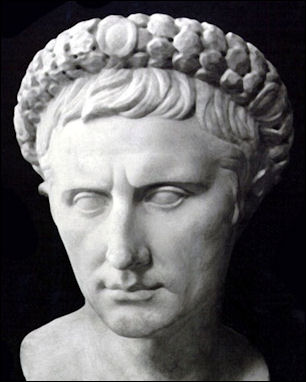

Augustus (Octavian) At the time of his romance with Cleopatra, Antony was battling Octavian (the bastard son of Caesar) for the emperorship of the Roman Empire. Back in Rome, Antony's third wife Fulva raised an army to fight Octavian and was soundly defeated and died. Antony made a temporary peace by arranging to marry Octavian's sister, Octavia. Antony left behind a pregnant Cleopatra in Alexandria and returned to Rome to marry Octavia. Antony and Octavia had two daughters. Octavia has always been portrayed sympathetically as the scorned woman. In Shakespeare play Cleopatra stabs the messenger who brings news of Antony's marriage. but that most likely didn't happen, with Cleopatra seeing the political necessity of the union.

Antony was later united with Cleopatra in Antioch. He married her under eastern law and divorced Octavia, who was pregnant at the time. Antony then launched his Parthian campaign and was miserable defeated and lost half his army. He responded to this by becoming a drunk, threatening suicide and mistreated his popular Roman wife. After this Octavia offered to help Antony but Antony refused and then appeared with Cleopatra, calling her the "Queen of Kings" and declared her son Caeserion as "King of Kings." Antony then announced that Caesarian, not Octavian, was Julius Caesar's true heir. Octavian was obviously not pleased by these events.

In 34 B.C. Octavian seized Antony's will from the Temple of the Vestal Virgins. The will revealed that Antony planned to be buried in Alexandria, not Rome, with Cleopatra. This infuriated the citizens of Rome. There were reports that Antony was wearing a Greek “ chlamy” not a Roman toga and planned to leave Rome to Cleopatra. A year later the Roman court declared war on Egypt and the “harlot queen.” If Antony and Cleopatra had seized the moment and attacked Italy then they might have prevailed but instead they sailed to Greece, where they stayed for a year, enjoying themselves and organizing a drama festival, and were trapped on the west coast of Greece near the port of Actium

RELATED ARTICLES:

AFTER THE ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, FAMILY, SOURCES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MARC ANTONY: HIS LIFE, RELATIONS WITH CAESAR AND MILITARY CAMPAIGNS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO'S MURDER, EVENTS AFTER CAESARS'S DEATH AND THE END OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.): LOOKS, SEX LIFE, FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA AND MARC ANTONY: ROMANCE, EVENTS, EXTRAVAGANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF ACTIUM europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece and Rome: House of Ptolemy houseofptolemy.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; llustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Noble Ruin: Mark Antony, Civil War, and the Collapse of the Roman Republic”

by W. Jeffrey Tatum Amazon.com

“Cleopatra and Antony” by Diana Preston, Amazon.com, well-written and engaging rehashing of the story;

“Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2010) Amazon.com, emphasizes the military side of their relationship.

“Antony and Cleopatra” (Folger Shakespeare Library) by William Shakespeare Amazon.com;

“Mark Antony: A Life” by Patricia Southern (2012) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff (2010) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Diane Stanley (1998) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: the Last Queen of Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesly (2008) Amazon.com;

“The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium” by Barry S. Strauss (2022) Amazon.com

“Sea of Flames: A thrilling account of the Battle of Actium” (2024) by Alistair Forrest Amazon.com;

“Actium 31 BC: Downfall of Antony and Cleopatra” by Si Sheppard , Christa Hook (Illustrator) (2009) Amazon.com;

“Octavian: Rise to Power: The Early Years of Caesar” by Patrick J. Parrelli (2015) Amazon.com;

“Augustus: First Emperor of Rome” by Adrian Goldsworthy (Yale University Press, 2014); Amazon.com;

“The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” by Toby Wilkinson (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Last Pharaohs: Egypt Under the Ptolemies, 305–30 BC” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies” by Guy de la Bedoyere (2024) Amazon.com;

“Alexandria: The City that Changed the World” by Islam Issa (2023) Amazon.com;

“Roman Egypt” by Roger S. Bagnall (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt” by Christina Riggs (2020) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Showdown Between Octavian and Antony

The strong feeling at Rome against Antony, Octavian was able to use to his own advantage. But he wished it to appear that he was following, and not directing, the will of the people. He therefore made no attempt to force an issue with Antony, but bided his time. The people suspected Antony of treasonable designs, as they saw his military preparations, which might be used to enthrone himself as king of the East, or to install Cleopatra as queen of Rome. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Marc Antony

All doubt as to Antony’s real character and purpose was settled when his will was found and published. In it he had made the sons of Cleopatra his heirs, and ordered his own body to be buried at Alexandria beside that of the Egyptian queen. This was looked upon as an insult to the majesty of Rome. The citizens were aroused. They demanded that war be declared against the hated triumvir. Octavian suggested that it would be more wise to declare war against Cleopatra than against Antony and the deluded citizens who had espoused his cause. Thus what was really a civil war between Octavian and Antony assumed the appearance of a foreign war between Rome and Egypt. But Antony well understood against whom the war was directed; and he replied by publicly divorcing Octavia, and accepting his real position as the public enemy of Rome. \~\

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The stage was set for a final breach between Octavian and Antony. Lepidus had always been much closer to Antony than to Octavian, so his ouster (as the death of Crassus had done) removed a major obstacle to open rivalry between his colleagues. Moreover, Antony was flouting the new marriage to Octavia by continuing to cavort with Cleopatra, who had borne him twins in 40 B.C.. He spent 36-34 B.C. in a vigorous but not very effective campaign against the Parthians, then returned to Egypt and his new "wife" Cleopatra. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“At the minimum, she hoped to use Antony to return Egypt to some of its former greatness, as in the days when the Ptolemies controlled a large piece of the old empire of Alexander the Great. But her true intentions and ways are difficult to reconstruct because she became a major target of the Augustan propaganda machine, which represented her as corrupt and scheming, hoping to conquer Rome and rule it, even to move the capital of the Empire to Alexandria (unthinkable!), she as Queen dominating Antony as King. As Syme puts it, "the propaganda of Octavianus magnified Cleopatra beyond all measure and decency. To ruin Antonius it was not enough that she should be a siren: she must be made a Fury — fatale monstrum (Horace, Odes 1. 37. 21). It is true that Antony had been enjoying playing the divine monarch. After all, in Egypt Cleopatra was both the Queen and the living incarnation of the goddess Isis. For the purposes of the state religion, Pompey played her consort Dionysus / Osiris. All this would be considered harmless, so long as it stayed in Egypt; in Rome it would be anathema. ^*^

“The falling out was precipitated by Antony's declaration that Caesarion, Caesar's supposed son by Cleopatra, was the legitimate heir of Caesar. In 33 the triumvirate, which had been extended for an additional five years, formally expired and was not renewed. Octavian and Antony's partisans at Rome spent the year attacking each other, and Antony signaled the end of the cooperation by divorcing Octavia. Octavian, consul for 31 B.C., procured an oath of personal allegiance from all of Italy and got a formal declaration (complete with fetiales proclaiming it iustum) of war against Cleopatra. Yet again the theatre for a decisive phase in the civil conflict would be Greece. The rivals met at Actium, where Octavian's fleet blockaded Antony and Cleopatra until the pair, hampered by desertions and short of supplies, was forced to abandon the position. In the summer of the next year Octavian chased the lovers to Egypt, where they evaded his wrath by committing suicide. Caesarion, of course, had to die. The challenge facing Octavian now was how to stabilize the republic without giving up power.” ^*^

Battle of Actium

While Antony and Cleopatra were trapped in Actium 400 ships and 80,000 infantrymen under Octavian's command approached Anthony's army from the north and cut of his supply lines in the south. Cleopatra reportedly was the one who urged Antony to make a final stand at sea. Cleopatra was put in charge of third of the fleet and ultimately showed that her military skill did not match her political skills

During the naval Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. the forces of Antony and Cleopatra were defeated by Octavian, whose navy was made up of smaller, faster ships that outmaneuvered the larger ships of Antony and Cleopatra's fleet after hard fighting and a lot of bloodshed. Many of the ships had battering rams, and many of the ships that sunk burned and were dragged down by their heavy battering rams. In 1993, objects believed to be from Anthony's fleet were discovered two miles off the west coast of Greece.

Before the battle had even begun, Cleopatra is said to have withdrawn her 60 ships, including her flagship containing Egypt's treasury. According to one account Antony abandoned his forces to pursue Cleopatra. In the run up to the battle Antony and Cleopatra staged a theater festival at Samos and neglected their supply lines.

Antony and Cleopatra Flee to Libya and Egypt

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “After Antony had reached the coast of Libya and sent Cleopatra forward into Egypt from Paraetonium, he had the benefit of solitude without end, roaming and wandering about with two friends, one a Greek, Aristocrates a rhetorician, and the other a Roman, Lucilius, about whom I have told a story elsewhere. He was at Philippi, and in order that Brutus might make his escape, pretended to be Brutus and surrendered himself to his pursuers. His life was spared by Antony on this account, and he remained faithful to him and steadfast up to the last crucial times. When the general to whom his forces in Libya had been entrusted brought about their defection, Antony tried to kill himself, but was prevented by his friends and brought to Alexandria. Here he found Cleopatra venturing upon a hazardous and great undertaking. The isthmus, namely, which separates the Red Sea from the Mediterranean Sea off Egypt and is considered to be the boundary between Asia and Libya, in the part where it is most constricted by the two seas and has the least width, measures three hundred furlongs. Here Cleopatra undertook to raise her fleet out of water and drag the ships across, and after launching them in the Arabian Gulf with much money and a large force, to settle in parts outside of Egypt, thus escaping war and servitude. But since the Arabians about Petra burned the first ships that were drawn up, and Antony still thought that his land forces at Actium were holding together, she desisted, and guarded the approaches to the country. And now Antony forsook the city and the society of his friends, and built for himself a dwelling in the sea at Pharos, by throwing a mole out into the water. Here he lived an exile from men, and declared that he was contentedly imitating the life of Timon, since, indeed, his experiences had been like Timon's; for he himself also had been wronged and treated with ingratitude by his friends, and therefore hated and distrusted all mankind. [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

Later, Antony and Cleopatra “sent an embassy to Caesar in Asia, Cleopatra asking the realm of Egypt for her children, and Antony requesting that he might live as a private person at Athens, if he could not do so in Egypt. But owing to their lack of friends and the distrust which they felt on account of desertions, Euphronius, the teacher of the children, was sent on the embassy. For Alexas the Laodicean, who had been made known to Antony in Rome through Timagenes and had more influence with him than any other Greek, who had also been Cleopatra's most effective instrument against Antony and had overthrown the considerations arising in his mind in favour of Octavia, had been sent to keep Herod the king from apostasy; but after remaining there and betraying Antony he had the audacity to come into Caesar's presence, relying on Herod. Herod, however, could not help him, but the traitor was at once confined and carried in fetters to his own p0 country, where he was put to death by Caesar's orders. Such was the penalty for his treachery which Alexas paid to Antony while Antony was yet alive.

“Caesar would not listen to the proposals for Antony, but he sent back word to Cleopatra that she would receive all reasonable treatment if she either put Antony to death or cast him out. He also sent with the messengers one of his own freedmen, Thyrsus, a man of no mean parts, and one who would persuasively convey messages from a young general to a woman who was haughty and astonishingly proud in the matter of beauty. This man had longer interviews with Cleopatra than the rest, and was conspicuously honoured by her, so that he roused suspicion in Antony, who seized him and gave him a flogging, and then sent him back to Caesar with a written message stating that Thyrsus, by his insolent and haughty airs, had irritated him, at a time when misfortunes made him easily irritated. "But if thou dost not like the thing," he said, "thou has my freedman Hipparchus; hang him up and give him a flogging, and we shall be quits." After this, Cleopatra tried to dissipate his causes of complaint and his suspicions by paying extravagant court to him; her own birthday she kept modestly and in a manner becoming to her circumstances, but she celebrated his with an excess of all kinds of splendour and costliness, so that many of those who were bidden to the supper came poor and went away rich. Meanwhile Caesar was being called home by Agrippa, who frequently wrote him from Rome that matters there greatly needed his presence.

Final Campaign Against Cleopatra in Syria and Egypt

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Accordingly, the war was suspended for the time being; but when the winter was over, Caesar (Octavian) again marched against his enemy through Syria, and his generals through Libya. When Pelusium was taken there was a rumour that Seleucus had given it up, and not without the consent of Cleopatra; but Cleopatra allowed Antony to put to death the wife and children of Seleucus, and she herself, now that she had a tomb and monument built surpassingly lofty and beautiful, which she had erected near the temple of Isis, collected there the most valuable of the royal treasures, gold, silver, emeralds, pearls, ebony, ivory, and cinnamon; and besides all this she put there great quantities of torch-wood and tow, so that Caesar was anxious about the reason, and fearing lest the woman might become desperate and burn up and destroy this wealth, kept sending on to her vague hopes of kindly treatment from him, at the same time that he advanced with his army against the city. But when Caesar had taken up position near the hippodrome, Antony sallied forth against him and fought brilliantly and routed his cavalry, and pursued them as far as their camp. Then, exalted by his victory, he went into the palace, kissed Cleopatra, all armed as he was, and presented to her the one of his soldiers who had fought most spiritedly. Cleopatra gave the man as a reward of valour a golden breastplate and a helmet. The man took them, of course, — and in the night deserted to Caesar. [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

“And now Antony once more sent Caesar a challenge to single combat. But Caesar answered that Antony had many ways of dying. Then Antony, conscious that there was no better death for him than that by battle, determined to attack by land and sea at once. And at supper, we are told, he bade the slaves pour out for him and feast him more generously; for it was uncertain, he said, whether they would be doing this on the morrow, or whether they would be serving other masters, while he himself would be lying dead, a mummy and a nothing. Then, seeing that his friends were weeping at these words, he declared that he would not lead them out to battle, since from it he sought an honourable death for himself rather than safety and victory.

“During this night, it is said, about the middle of it, while the city was quiet and depressed through fear and expectation of what was coming, suddenly certain harmonious sounds from all sorts of instruments were heard, and the shouting of a throng, accompanied by cries of Bacchic revelry and satyric leapings, as if a troop of revellers, making a great tumult, were going forth from the city; and their course seemed to lie about through the middle of the city toward the outer gate which faced the enemy, at which point the tumult became loudest and then dashed out. Those who sought the meaning of the sign were of the opinion that the god to whom Antony always most likened and attached himself was now deserting him.

“At daybreak, Antony in person posted his infantry on the hills in front of the city, and watched his ships as they put out and attacked those of the enemy; and as he expected to see something great accomplished by them, he remained quiet. But the crews of his ships, as soon as they were near, p saluted Caesar's crews with their oars, and on their returning the salute changed sides, and so all the ships, now united into one fleet, sailed up towards the city prows on. No sooner had Antony seen this than he was deserted by his cavalry, which went over to the enemy, and after being defeated with his infantry he retired into the city, crying out that he had been betrayed by Cleopatra to those with whom he waged war for her sake. But she, fearing his anger and his madness, fled for refuge into her tomb and let fall the drop-doors, which were made strong with bolts and bars; then she sent messengers to tell Antony that she was dead. Antony believed that message, and saying to himself, "Why doest thou longer delay, Antony? Fortune has taken away thy sole remaining excuse for clinging to life," he went into his chamber. Here, as he unfastened his breastplate and laid it aside, he said: "O Cleopatra, I am not grieved to be bereft of thee, for I shall straightway join thee; but I am grieved that such an imperator as I am has been found to be inferior to a woman in courage."

Cleopatra and Octavian

Cleopatra Meeting with Octavian

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “ “After a few days Caesar himself came to talk with her and give her comfort. She was lying on a mean pallet-bed, clad only in her tunic, but sprang up as he entered and thew herself at his feet; her hair and face were in terrible disarray, her voice trembled, and her eyes were sunken. There were also visible many marks of the cruel blows upon her bosom; in a word, her body seemed to be no better off than her spirit. Nevertheless, the charm for which she was famous and the boldness of her beauty were not altogether extinguished, but, although she was in such a sorry plight, they shone forth from within and made themselves manifest in the play of her features. [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

After Caesar had bidden her to lie down and had seated himself near her, she began a sort of justification of her course, ascribing it to necessity and fear of Antony; but as Caesar opposed and refuted her on every point, she quickly changed her tone and sought to move his pity by prayers, as one who above all things clung to life. And finally she gave him a list which she had of all her treasures; and when Seleucus, one of her stewards, showed conclusively that she was stealing away and hiding some of them, she sprang up, seized him by the hair, and showered blows upon his face. And when Caesar, with a smile, stopped her, she said: "But is it not a monstrous thing, O Caesar, that when thou hast deigned to come to me and speak to me though I am in this wretched plight, my slaves denounce me for reserving some women's adornments, — not for myself, indeed, unhappy woman that I am, — but that I may make trifling gifts to Octavia and thy Livia, and through their intercession find thee merciful and more gentle?" Caesar was pleased with this speech, being altogether of the opinion that she desired to live. He told her, therefore, that he left these matters for her to manage, and that in all p other ways he would give her more splendid treatment than she could possibly expect. Then he went off, supposing that he had deceived her, but they rather deceived by her.

Death of Antony and Cleopatra

death of Cleopatra

Death of Antony Antony's defeat spelled the end of Cleopatra' power. She placed her treasure of gold, silver, pearls and in a huge mausoleum with enough fuel to burn it down to keep her treasures from falling into Roman hands.. She then locked herself with her serving maids in her palace.

Cleopatra then reportedly tried to seduce to Octavian, but when she failed she chose to commit suicide at the age of 39 rather than face the humiliation of the rejection and being brought to Rome as a prisoner. She was found dead, one story goes, on a bed of pure gold, dressed in rich robes of Isis, with a message that she wanted to be buried in Rome with Antony.

In the meantime Antony, no doubt upset by the recent events, tried to commit suicide by falling on his sword. When he fell he missed his vital organs and remained alive for about a week before he died. He reportedly lived long enough to be hauled through a window in Cleopatra's mausoleum where he is said to have died in Cleopatra's arms. In some accounts Antony was brought to the mausoleum on the first of August ten days or so before Cleopatra killed herself .

Plutarch wrote: “Antony, defeated and ruined, committed suicide; and Cleopatra followed his example rather than be led a captive in a Roman triumph. Together this wretched pair were laid in the mausoleum of the Ptolemies. Egypt was annexed as a province of the new empire (30 B.C.). Octavian returned to Rome (29 B.C.), where he was given the honors of a triple triumph—for Dalmatia (where he had gained some previous victories), for Actium, and for Egypt. The temple of Janus was now closed for the first time since the second Punic war; and the Romans, tired of war and of civil strife, looked upon the triumph of Octavian as the dawn of a new era of peace and prosperity.” [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

Octavian honored Antony's will. Antony and Cleopatra were buried together (the location of grave site is a mystery). The Roman historian Dio Cassius reported that Cleopatra's body was embalmed as Antony's had been, and Plutarch noted that on the orders of Octavian, the last queen of Egypt was buried beside her defeated Roman consort. Sixteen centuries later Shakespeare proclaimed: "No grave upon the earth shall clip in it / a pair so famous." [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011]

With Cleopatra's death in 30 B.C., the Ptolemaic Dynasty ended. Octavian lured Ptolemy Caesarian, Cleopatra's son with Julius Caesar, back to Alexandria and had him murdered. Octavian adopted the children Cleopatra had with Antony. In 30 B.C. Egypt also became a province of Rome. It would not recover its autonomy until the 20th century.

Plutarch on the Death of Marc Antony

Death of Antony Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Now, Antony had a trusty slave named Eros. Him Antony had long before engaged, in case of need, to kill him, and now demanded the fulfilment of his promise. So Eros drew his sword and held it up as though he would smite his master, but then turned his face away and slew himself. And as he fell at his master's feet Antony said: "Well done, Eros! though thou wast not able to do it thyself, thou teachest me what I must do"; and running himself through the belly he dropped upon the couch. But the wound did not bring a speedy death. Therefore, as the blood ceased flowing after he had lain down, he p came to himself and besought the bystanders to give him the finishing stroke. But they fled from the chamber, and he lay writhing and crying out, until Diomedes the secretary came from Cleopatra with orders to bring him to her in the tomb. [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

“Having learned, then, that Cleopatra was alive, Antony eagerly ordered his servants to raise him up, and he was carried in their arms to the doors of her tomb. Cleopatra, however, would not open the doors, but showed herself at a window, from which she let down ropes and cords. To these Antony was fastened, and she drew him up herself, with the aid of the two women whom alone she had admitted with her into the tomb. Never, as those who were present tell us, was there a more piteous sight. Smeared with blood and struggling with death he was drawn up, stretching out his hands to her even as he dangled in the air. For the task was not an easy one for the women, and scarcely could Cleopatra, with clinging hands and strained face, pull up the rope, while those below called out encouragement to her and shared her agony. And when she had thus got him in and laid him down, she rent her garments over him, beat and tore her breasts with her hands, wiped off some of his blood upon her face, and called him master, husband, and imperator; indeed, she almost forgot her own ills in her pity for his. But Antony stopped her lamentations and asked for a drink of wine, either because he was thirsty, or in the hope of a speedier release. When he had drunk, he advised her to consult her own safety, if she could do it without disgrace, and among all the companions of Caesar to put most confidence in p Proculeius, and not to lament him for his last reverses, but to count him happy for the good things that had been his, since he had become most illustrious of men, had won greatest power, and now had been not ignobly conquered, a Roman by a Roman.

“Scarcely was he dead, when Proculeius came from Caesar. For after Antony had smitten himself and while he was being carried to Cleopatra, Dercetaeus, one of his body-guard, seized Antony's sword, concealed it, and stole away with it; and running to Caesar, he was the first to tell him of Antony's death, and showed him the sword all smeared with blood. When Caesar heard these tidings, he retired within his tent and wept for a man who had been his relation by marriage, his colleague in office and command, and his partner in many undertakings and struggles. Then he took the letters which had passed between them, called in his friends, and read the letters aloud, showing how reasonably and justly he had written, and how rude and overbearing Antony had always been in his replies. After this, he sent Proculeius, bidding him, if possible, above all things to get Cleopatra into his power alive; for he was fearful about the treasures in her funeral pyre, and he thought it would add greatly to the glory of his triumph if she were led in the procession. Into the hands of Proculeius, however, Cleopatra would not put herself; but she conferred with him after he had come close to the tomb and stationed himself outside at a door which was on a level with the ground. The door was strongly fastened with bolts and bars, but allowed a passage for the voice. So they conversed, Cleopatra p asking that her children might have the kingdom, and Proculeius bidding her be of good cheer and trust Caesar in everything.

death of Marc Antony from Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, Act 4, Scene 14

“After Proculeius had surveyed the place, he brought back word to Caesar, and Gallus was sent to have another interview with the queen; and coming up to the door he purposely prolonged the conversation. Meanwhile Proculeius applied a ladder and went in through the window by which the women had taken Antony inside. Then he went down at once to the very door at which Cleopatra was standing and listening to Gallus, and he had two servants with him. One of the women imprisoned with Cleopatra cried out, "Wretched Cleopatra, thou art taken alive," whereupon the queen turned about, saw Proculeius, and tried to stab herself; for she had at her girdle a dagger such as robbers wear. But Proculeius ran swiftly to her, threw both his arms about her, and said: "O Cleopatra, thou art wronging both thyself and Caesar, by trying to rob him of an opportunity to show great kindness, and by fixing upon the gentlest of commanders the stigma of faithlessness and implacability." At the same time he took away her weapon, and shook out her clothing, to see whether she was concealing any poison. And there was also sent from Caesar one of his freedmen, Epaphroditus, with injunctions to keep the queen alive by the strictest vigilance, but otherwise to make any concession that would promote her ease and pleasure.

“Antony was fifty-six years of age, according to some, according to others, fifty-three. Now, the statues of Antony were torn down, but those of Cleopatra were left standing, because Archibius, one of her friends, gave Caesar two thousand talents, in order that they might not suffer the same fate as Antony's.

“Antony left seven children by his three wives, of whom Antyllus, the eldest, was the only one who was put to death by Caesar; the rest were taken up by Octavia and reared with her own children. Cleopatra, the daughter of Cleopatra, Octavia gave in marriage to Juba, the most accomplished of kings, and Antony, the son of Fulvia, she raised so high that, while Agrippa held the first place in Caesar's estimation, and the sons of Livia the second, Antony was thought to be and really was third. By Marcellus Octavia had two daughters, and one son, Marcellus, whom Caesar made both his son and his son-in law, and he gave one of the daughters to Agrippa. But since Marcellus died very soon after his marriage and it was not easy for Caesar to select from among his other friends a son-in law whom he could trust, Octavia proposed that Agrippa should take Caesar's daughter to wife, and put away her own. First Caesar was persuaded by her, then Agrippa, whereupon p she took back her own daughter and married her to young Antony, while Agrippa married Caesar's daughter. Antony left two daughters by Octavia, of whom one was taken to wife by Domitius Ahenobarbus, and the other, Antonia, famous for her beauty and discretion, was married to Drusus, who was the son of Livia and the step-son of Caesar. From this marriage sprang Germanicus and Claudius; of these, Claudius afterwards came to the throne, and of the children of Germanicus, Caius reigned with distinction,i but for a short time only, and was then put to death with his wife and child, and Agrippina, who had a son by Ahenobarbus, Lucius Domitius, became the wife of Claudius Caesar. And Claudius, having adopted Agrippina's son, gave him the name of Nero Germanicus. This Nero came to the throne in my time. He killed his mother, and by his folly and madness came near subverting the Roman empire. He was the fifth in descent from Antony.

Plutarch on Cleopatra’s Death

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Now, there was a young man of rank among Caesar's companions, named Cornelius Dolabella. This man was not without a certain tenderness for Cleopatra; and so now, in response to her request, he secretly sent word to her that Caesar himself was preparing to march with his land forces through Syria, and had resolved to send off her and her children within three days. After Cleopatra had heard this, in the first place, she begged Caesar that she might be permitted to pour libations for Antony; and when the request was granted, she had herself carried to the tomb, and embracing the urn which held his ashes, in company with the women usually about her, she said: "Dear Antony, I buried thee but lately with hands still free; now, however, I pour libations for thee as a captive, and so carefully guarded that I cannot either with blows or tears disfigure this body of mine, which is a slave's body, and closely watched that it may grace the triumph over thee. Do not expect other honours or libations; these are the last from Cleopatra the captive. For though in life nothing could part us from each other, in death we are likely to change places; thou, the Roman, lying buried here, while I, the hapless woman, lie in Italy, and get only so much of thy country as my portion. But if indeed there is any might or power in the gods of that country (for the gods of this country have betrayed us), do not abandon thine own wife while she lives, nor permit a p triumph to be celebrated over myself in my person, but hide and bury me here with thyself, since out of all my innumerable ills not one is so great and dreadful as this short time that I have lived apart from thee." [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

dead Cleopatra

“After such lamentations, she wreathed and kissed the urn, and then ordered a bath to be prepared for herself. After her bath, she reclined at table and was making a sumptuous meal. And there came a man from the country carrying a basket; and when the guards asked him what he was bringing there, he opened the basket, took away the leaves, and showed them that the dish inside was full of figs. The guards were amazed at the great size and beauty of the figs, whereupon the man smiled and asked them to take some; so they felt no mistrust and bade him take them in. After her meal, however, Cleopatra took a tablet which was already written upon and sealed, and sent it to Caesar, and then, sending away all the rest of the company except her two faithful women, she closed the doors.

“But Caesar opened the tablet, and when he found there lamentations and supplications of one who begged that he would bury her with Antony, he quickly knew what had happened. At first he was minded to go himself and give aid; then he ordered messengers to go with all speed and investigate. But the mischief had been swift. For though his messengers came on the run and found the guards as yet aware of nothing, when they opened the doors they found Cleopatra lying dead upon a golden couch, arrayed in royal state. And of her two women, the one called Iras was dying at her feet, while Charmion, already tottering and heavy-handed, was p trying to arrange the diadem which encircled the queen's brow. Then somebody said in anger: "A fine deed, this, Charmion!" "It is indeed most fine," she said, "and befitting the descendant of so many kings." Not a word more did she speak, but fell there by the side of the couch.

“It is said that the asp was brought with those figs and leaves and lay hidden beneath them, for thus Cleopatra had given orders, that the reptile might fasten itself upon her body without her being aware of it. But when she took away some of the figs and saw it, she said: "There it is, you see," and baring her arm she held it out for the bite. But others say that the asp was kept carefully shut up in a water jar, and that while Cleopatra was stirring it up and irritating it with a golden distaff it sprang and fastened itself upon her arm. But the truth of the matter no one knows; for it was also said that she carried about poison in a hollow comb and kept the comb hidden in her hair; and yet neither spot nor other sign of poison broke out upon her body. Moreover, not even was the reptile seen within the chamber, though people said they saw some traces of it near the sea, where the chamber looked out upon it with its windows. And some also say that Cleopatra's arm was seen to have two slight and indistinct punctures; and this Caesar also seems to have believed. For in his triumph an image of Cleopatra herself with the asp clinging to her was carried in the procession.h These, then, are the various accounts of what happened. “But Caesar, although vexed at the death of the woman, admired her lofty spirit; and he gave orders p that her body should be buried with that of Antony in splendid and regal fashion. Her women also received honourable interment by his orders. When Cleopatra died she was forty years of age save one, and had shared her power with Antony more than fourteen.

Fate of Cleopatra's Son with Caesar

Cleopatra had one son, Caesarion, with Caesar and three children — Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II and Ptolemy Philadelphus — with Marc Antony. Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Ptolemy Caesar “Theos Philopator Philometor”—“Ptolemy Caesar, The God Who Loves His Father and Mother”—became king of Egypt at the tender age of three. His alleged father, Julius Caesar, had been assassinated several months earlier, and his mother, Queen Cleopatra VII, placed him on the throne to solidify her power as queen of Egypt. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, October 16, 2020]

Better known to history by his Greek nickname “Caesarion,” or “little Caesar,” Cleopatra’s son reigned only a short time; his rule ended with his murder, shortly after the suicide of Cleopatra in 30 B.C. The deaths of mother and son brought an end to the Ptolemaic line of rulers who had controlled Egypt since the time of Alexander the Great.

After Octavian defeated Cleopatra and Antony on September 2, 31 B.C. by vanquished their forces at the Battle of Actium, the defeated pair retreated to Alexandria. Cleopatra decided it was safer to send Caesarion out of the city. He headed south in the company of his tutor, who took him up the Nile to the village of Copt (Qift), not far from Thebes. From there, caravans set off, passing through the eastern desert to the commercial port of Berenice, on the shores of the Red Sea. Caesarion’s only feasible escape route was across these inhospitable lands. If he made it to Berenice, he would have a chance to get out of Egypt and set sail for Arabia or even to India.

While making his way to the port that might have allowed him a route to exile, Caesarion learned that Roman troops had entered Alexandria and that his mother and Mark Antony were both dead. Had he carried on with his escape plan, Caesarion might have survived, but his tutor suggested that Octavian would take pity on the orphan.

Indeed, Octavian had considered sparing the young man’s life. One of his confidants convinced him otherwise; it was inappropriate, he said, for there to be “too many Caesars.” So when Caesarion arrived in Alexandria to meet Octavian in August 30 B.C., he was immediately executed. The dream of a Roman-Egyptian pharaoh vanished, and the ancient Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt died with Caesarion.

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: Caesarion, who was said to be Cleopatra's son by Julius Caesar, was sent by his mother, with much treasure, into India, by way of Ethiopia. There Rhodon, another tutor like Theodorus, persuaded him to go back, on the ground that Caesar invited him to take the kingdom. But while Caesar was deliberating on the matter, we are told that Areius said: "Not a good thing were a Caesar too many." [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

“As for Caesarion, then, he was afterwards put to death by Caesar, after the death of Cleopatra; but as for Antony, though many generals and kings asked for his body that they might give it burial, Caesar would not take it away from Cleopatra, and it was buried by her hands in sumptuous and royal fashion, such things being granted her for the purpose as she desired. But in consequence of so much grief as well as pain (for her breasts were wounded and inflamed by the blows she gave them) a fever assailed her, and she welcomed it as an excuse for abstaining from food and so releasing herself from life without hindrance. Moreover, there was a physician in her company of intimates, Olympus, to whom she told the truth, and she had his counsel and assistance in compassing her death, as Olympus himself testifies in a history of these events which he published. But Caesar was suspicious, and plied her with threats and fears regarding her children, by which she was laid low, as by engines of war, and surrendered her body for such care and nourishment as was desired.

Fate of Cleopatra's Children with Marc Antony

After he had their brother Caesarion executed, Octavian took Cleopatra’s three other children (all by Mark Antony) back with him to Rome where Octavian presented them in chains to the Roman people and paraded them through the streets in triumphal procession. Some sources say Octavian wished to execute them after the triumph, but that Octavia the Younger, his elder sister and the late Mark Antony’s ex-wife, convinced him to let her raise them alongside her own children.

The fate of the two boys is unknown. None of the popular historians of the time mention either Alexander Helios or Ptolemy Philadelphus again, which leads many to believe they died in childhood. Cleopatra Selene did survive; she married Juba II, king of Numidia and then Mauritania, and had several children with him.

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “As for the children of Antony, Antyllus, his son by Fulvia, was betrayed by Theodorus his tutor and put to death; and after the soldiers had cut off his head, his tutor took away the exceeding precious stone which the boy wore about his neck and sewed it into his own girdle; and though he denied the deed, he was convicted of it and crucified. Cleopatra's children, together with their attendants, were kept under guard and had generous treatment.

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”:“As for the children of Antony, Antyllus, his son by Fulvia, was betrayed by Theodorus his tutor and put to death; and after the soldiers had cut off his head, his tutor took away the exceeding precious stone which the boy wore about his neck and sewed it into his own girdle; and though he denied the deed, he was convicted of it and crucified. Cleopatra's children, together with their attendants, were kept under guard and had generous treatment.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024