Home | Category: Age of Augustus

CLEOPATRA

Antony and Cleopatra

Cleopatra (69-30 B.C.) is one of the most famous women of all a time. A Greek Queen of Egypt, she played a major role in the extension of the Roman Empire and was a lover of Julius Caesar, the wife of Marc Antony and a victim of Augustus Caesar, the creator of the Roman Empire. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011; Stacy Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010; Judith Thurman, The New Yorker, May 7, 2001 and November 15, 2010; Barbara Holland, Smithsonian, February 1997]

According to National Geographic: Cleopatra was the last member of the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt from 305 B.C. to 30 B.C. Although often portrayed as a femme fatale, she was a shrewd politician, using intelligence more than feminine wiles in relationships with Rome. In 47 B.C., when Julius Caesar came to Alexandria, she was in exile, fearful of the ambitions of her brother Ptolemy XIII, so she had herself carried in a sack into her palace, where Caesar was staying. He installed her as queen; they became allies and lovers and she bore him a son, Caesarion.

Determined to protect herself and her son’s future after Caesar’s death, Cleopatra wooed Mark Antony. He was smitten, and the two began an affair that produced three children. Their life together was luxurious. After the loss at Actium, Cleopatra and Antony tried to negotiate with Octavian. They failed, and in 30 B.C., they both committed suicide.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.): LOOKS, SEX LIFE, FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA'S RULE (51-30 B.C.): POLITICS, LEADERSHIP AND TIES WITH THE ROMANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA LEGACY: POPULARITY, CELEBRITY, ALLURE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, FAMILY, SOURCES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MARC ANTONY: HIS LIFE, RELATIONS WITH CAESAR AND MILITARY CAMPAIGNS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF ACTIUM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND DEATHS OF ANTONY, CLEOPATRA AND THEIR CHILDREN europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece and Rome: House of Ptolemy houseofptolemy.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; llustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cleopatra and Antony” by Diana Preston, Amazon.com, well-written and engaging rehashing of the story;

“Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2010) Amazon.com, emphasizes the military side of their relationship.

“Antony and Cleopatra” (Folger Shakespeare Library) by William Shakespeare Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff (2010) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Diane Stanley (1998) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: the Last Queen of Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesly (2008) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Michael Grant (2000, 1972) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: Histories, Dreams and Distortions” by Lucy Hughes-Hallet (1990) Amazon.com;

“Women & Society in Greek & Roman Egypt” by Jane Rowlandson (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Memoirs of Cleopatra” by Margaret George (1997), Novel and Source of TV miniseries Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra's Daughter: A Novel” by Michelle Moran (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” by Toby Wilkinson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ptolemy I: King and Pharaoh of Egypt,” Illustrated, by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Last Pharaohs: Egypt Under the Ptolemies, 305–30 BC” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies” by Guy de la Bedoyere (2024) Amazon.com;

“Alexandria: The City that Changed the World” by Islam Issa (2023) Amazon.com;

“Roman Egypt” by Roger S. Bagnall (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt” by Christina Riggs (2020) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Marc Antony

Marcus Antonius (83–30 B.C.), commonly known as Marc or Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of Rome from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire. Antony was a relative and supporter of Julius Caesar, and he served as one of his generals during the conquest of Gaul and Caesar's civil war. After Caesar’s death he first united with Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus) and then fought with him over who would be the sole leader over the fast-growing Roman Empire.

After Caesar's death Marc Antony and his ally Lepidus ultimately prevailed in their war with Cassius and Brutus for control of Rome and divided the Roman Empire among themselves, with Antony getting the East and Lepidus getting the West. In 41 B.C., while on tour of his empire to make alliances and secure funds for attack on the Parthians in Iran, Antony met Cleopatra.

At that time, Anthony was handsome and had thick curly hair. He claimed he was a descendent of Hercules and sometimes identified himself with Dionysus. Plutarch described Antony as mellow and generous but a bit of slob. Cicero called him a "a kind of butcher or prizefighter" and said his all-night orgies made him "odius." He also had a reputation for getting so drunk at all-male parties that he threw up into his own toga.

Even though women and soldiers loved him, Antony's biographer Adrian Goldsworthy dismisses him as a “not an especially good general” and wrote: “There is no real trace of any long-held beliefs or causes on Antony's part” beyond “glory and profit,"

See Separate Article: MARC ANTONY: HIS LIFE, RELATIONS WITH CAESAR AND MILITARY CAMPAIGNS europe.factsanddetails.com

Cleopatra and Marc Antony

Cleopatra and Marc Antony

representations on coins Cleopatra and Marc Antony began their famous love affair after the death of Caesar when Octavian and Antony were fighting a civil war for control of Rome. Cleopatra was 29 years old at the time and is said to have purposely delayed setting out to meet him to heighten Antony's expectations. When she finally announced she was coming she sent the message: “For the good and happiness of Asia I am coming for a Festive reception...Venus has come to revel with Bacchus” Her arrival in a boat with priceless purple sails was immortalized in Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra . Plutarch described it as an act of mockery.

According to National Geographic: Antony left for Egypt as part of the triumvirs’ agreement to divide the empire. There, he fell for Cleopatra, and reports of their debauched conduct provided fodder to Antony’s enemies as Octavian was proving himself a model Roman: ensuring people had enough to eat, overseeing improvements to the city’s water system, and settling into a stable, conservative marriage with Livia Drusilla. In 32 B.C., Octavian claimed to have proof that Antony was about to move the capital of the republic to Alexandria and declared war. In response, Antony and Cleopatra tried to invade Italy, but they were blockaded in the Bay of Actium. Octavian’s army was victorious on land and sea, sending the doomed couple fleeing back to Egypt. There, they committed suicide.[Source: National Geographic History, August 24, 2022]

For the sake of her kingdom and of her son, Caesarion, Cleopatra took Antony on a sumptuous cruise and a love affair ensued. This relationship has long been regarded as one of history’s most passionate, but historian Mary Beard revealed its more practical side: “Passion may have been one element of it. But their partnership was underpinned by something more prosaic: military, political, and financial needs.” [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, October 16, 2020]

Antony spent the winter of 41-40 B.C. in Egypt with Cleopatra. From their union twins were born and named after the astral deities: Alexander Helios (Sun) and Cleopatra Selene (Moon). Later, they had another son named Ptolemy Philadelphus. During this time, Cleopatra was also expanding her empire, gaining territory for Caesarion in southern Syria, Cyprus, and northern Africa.

Cleopatra’s greatest moment came during a ceremony held at the Alexandria gymnasium in 34 B.C., when Antony officially recognized her as queen of Egypt and bestowed on Caesarion the title “King of Kings.” Antony also formally recognized Caesarion as the legitimate son of Julius Caesar. Antony granted his three children with Cleopatra the title of royal highnesses and to his son Alexander Helios he promised territories and kingdoms.

Timeline of Events Involving Antony and Cleopatra

44 B.C. Octavian and Mark Antony compete for power after Julius Caesar's death.

41 B.C. To tap Egypt’s resources for his military campaigns, Antony invites Cleopatra to Tarsus. The two become lovers and allies.

40 B.C. After Cleopatra gives birth to his twins, Antony returns to Rome and is forced into a political marriage with Octavian's sister.

37 B.C. Antony rejoins Cleopatra, who becomes pregnant with their third child.

32 B.C. Octavian strips Antony of his powers and declares war on Cleopatra.

31 B.C. Octavian defeats the combined forces of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium.

30 B.C. Octavians invades Egypt and takes Alexandria. Antony commits suicide, and Cleopatra follows suit rather than face humiliation in Rome. [Source National Geographic]

Cleopatra Returns to Egypt

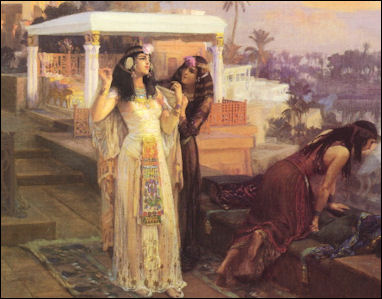

Cleopatra on the Terraces of Philae After Caesar's assassination, as Octavian, Marc Antony and Lepidus battled Cassius and Brutus for control of Rome, Cleopatra returned home to Egypt, at a time when it was suffering a famine and plague. While she was away her brother died and Egypt was under the rule of an imposter pretending to be the dead Ptolemy XIII. Without Caesar to back her up Cleopatra ousted the pretender, seized control of Egypt and adopted a position of neutrality in the Roman civil war.

As the undisputed leader of Egypt, Cleopatra named the toddler Ptolemy Caesarian as co-ruler and turned the country around from a debt-ridden colony into a powerful semi-autonomous state that was the richest in eastern Mediterranean. As leader she cracked on corruption, discouraged officials from taking bribes from farmers and built up Egypt's fleet.

Cleopatra ruled from Alexandria and lived in a palace a short distance from the Pharos Lighthouse, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. On the grounds was the Mousein, a center of philosophy and learning. The local people liked here because she spoke the local language and paid respects to Egyptian gods. At that point the Romans liked her because she brought in wealth for the empire.

Marc Antony at the Time He Met Cleopatra

Marc Antony and Lepidus ultimately prevailed in their war with Cassius and Brutus for control of Rome and divided the Roman Empire among themselves, with Antony getting the East and Lepidus getting the West. In 41 B.C., while on tour of his empire to make alliances and secure funds for attack on the Parthians in Iran, Antony met Cleopatra.

At that time, Anthony was handsome and had thick curly hair. He claimed he was a descendent of Hercules and sometimes identified himself with Dionysus. Plutarch described Antony as mellow and generous but a bit of slob. Cicero called him a "a kind of butcher or prizefighter" and said his all-night orgies made him "odius." He also had a reputation for getting so drunk at all-male parties that he threw up into his own toga. Even though women and soldiers him, Antony’s biographer Adrian Goldsworthy dismisses him as a “not an especially good general” and wrote: “There is no real trace of any long-held beliefs or causes on Antony’s part” beyond “glory and profit.”

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: In 42 B.C. Rome’s three most powerful men carved up the republic among them. The triumvirate of Lepidus, Octavian, and Mark Antony was an uneasy alliance after turbulent times. Placed in charge of the eastern provinces, Mark Antony found himself far from Rome and immersed in the Hellenistic culture he had always adored. It was a heady combination that drew him into the arms of Cleopatra, Egypt’s beguiling queen. [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

As Antony journeyed to take up his new responsibilities, amorous adventures ranked low on his agenda. The triumvirate that ruled over Rome’s vast territories needed to urgently restructure the army in the east, secure new sources of military funding, and launch a punitive expedition against the Parthians to avenge a humiliating defeat in 53 B.C. Julius Caesar had been planning such an expedition before his assassination, and Antony was keen to be seen to continue his great mentor’s work. He also knew that a major victory against a foreign foe would greatly enhance his personal prestige and power.

Mark Antony’s interests, however, extended beyond Roman politics. He had a deep love of the Greek Hellenistic culture that Alexander the Great’s conquests had firmly embedded in the lands that now formed Rome’s eastern provinces. The abundant cultural distractions helped to alleviate the heavy cares of state, and Antony took full advantage as he toured his territories. Visiting Athens, he won the sobriquet “Dionysus the giver of joy,” and traveling in Asia Minor, he was met in Ephesus by a spectacular procession of men and women dressed as satyrs and priestesses of Bacchus, the Roman god of revelry. The citizens of Ephesus bestowed upon the Roman Antony the divine title of “Dionysus the benefactor.” (Learn more about Greek culture that Antony adored.

Cleopatra's Grand Entrance

Cleopatra and Marc Antony began their famous love affair in 42 B.C. in Tarsus in Asia Minor. According to Plutarch, Cleopatra arrived in Tarsus to meet Antony on a perfumed barge with purple sails. She was dressed as Aphrodite and was fanned by boys dressed like cupids. "Her rowers caressed the water with oars of silver which dipped in time to the music of the flute, accompanied by pipes and lutes...Instead of a crew the barge was lined with the most beautiful of her waiting women as Nerid and Graces, some at the steering oars, others at the tackles of the sails, and all the while indescribably rich perfume, exhaled from innumerable censers, was wafted from the vessel to the river banks."

Shakespeare wrote the purple sails on Cleopatra's barge were "so perfumed that the winds were lovesick with them." It is believed that Cleopatra wore a fragrance with resins like balsam and myrrh and spices like cinnamon, cardamon, iris root, saffron and marjoram. Cleopatra welcomed Antony into her bedroom, whose floor was covered with a foot and half of rose petals. In some rooms of her palace she hung nets scented with various fragrances. As a gift Antony gave Cleopatra Turkey's Mediterranean coast, the western part of Asia Minor, and parts of Syria, Phoenicia, Jordan and Cyprus. Antony returned to Egypt with Cleopatra, where he hunted and gambled and engaged in childish pranks. For fun the couple went slumming in the bars of Alexandria disguised as slaves.

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: Cleopatra dramatically played on Mark Antony’s fascination for Greek culture and his love of luxury. She approached Tarsus by sailing up the Cydnus River in a magnificent boat with a golden prow, purple sails, and silver oars. As musicians played, Cleopatra reclined under a gold-embroidered canopy dressed as Aphrodite, Greek goddess of love. She was fanned by youths dressed as Eros and waited upon by girls dressed as sea nymphs, while servants wafted perfume toward the gaping crowds lining the river. As sound and smell embellished this visually suggestive tableau, the impression made by Cleopatra must have been truly extraordinary. [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

Antony was overwhelmed by the spectacle. The Greek historian Plutarch describes a scene in which the Roman was abandoned in the city square as his attendants joined citizens racing to the river for a first glimpse of the queen. Caught off guard, Antony decided to invite Cleopatra to a banquet. However, the Egyptian queen was in complete control of events, and instead Antony found himself accepting her invitation to a feast she’d already prepared. According to Athenaeus, quoting Socrates of Rhodes, gold and precious gems dominated the decor of the dining hall, which was also hung with expensive carpets of purple and gold. Cleopatra provided expensive couches for Antony and his entourage, and to the triumvir’s amazement, the queen told him with a smile that they were a gift. Antony tried to reciprocate but soon realized he could not compete with Cleopatra.

Cleopatra's younger sister was captured by Julius Caesar in 47 B.C., and sent to live in Ephesus at the temple of Artemis. Six years later, following Cleopatra’s meeting with Mark Antony, the queen persuaded him to have her executed. According to Plutarch, the queen had been convinced that her conquest of Antony would be easier than her earlier seduction of Julius Caesar—she was now far more experienced in the ways of the world. At 28 she had the confidence, intelligence, and beauty of a mature woman. She was sure of winning over Antony through a combined assault of conspicuous consumption and generosity, proving both Egypt’s abundant resources and her famed seductive charms. By some accounts Cleopatra’s beauty would not have turned heads at first sight, but she was deeply charismatic and was noted for her sweetness of voice. Cleopatra also knew she had the advantage: Antony had seen her in Alexandria 14 years earlier and been captivated by her then. Now they fell wildly in love.

Plutarch on the Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Such being his temper, the last and crowning mischief that could befall him came in the love of Cleopatra, to awaken and kindle to fury passions that as yet lay still and dormant in his nature, and to stifle and finally corrupt any elements that yet made resistance in him of goodness and a sound judgment. He fell into the snare thus. When making preparation for the Parthian war, he sent to command her to make her personal appearance in Cilicia, to answer an accusation that she had given great assistance, in the late wars, to Cassius. Dellius, who was sent on this message, had no sooner seen her face, and remarked her adroitness and subtlety in speech, but he felt convinced that Antony would not so much as think of giving any molestation to a woman like this; on the contrary, she would be the first in favour with him. So he set himself at once to pay his court to the Egyptian, and gave her his advice, "to go," in the Homeric style, to Cilicia, "in her best attire," and bade her fear nothing from Antony, the gentlest and kindest of soldiers. She had some faith in the words of Dellius, but more in her own attractions; which, having formerly recommended her to Caesar and the young Cnaeus Pompey, she did not doubt might prove yet more successful with Antony. Their acquaintance was with her when a girl, young and ignorant of the world, but she was to meet Antony in the time of life when women's beauty is most splendid, and their intellects are in full maturity. She made great preparation for her journey, of money, gifts, and ornaments of value, such as so wealthy a kingdom might afford, but she brought with her her surest hopes in her own magic arts and charms. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

“She received several letters, both from Antony and from his friends, to summon her, but she took no account of these orders; and at last, as if in mockery of them, she came sailing up the river Cydnus, in a barge with gilded stern and outspread sails of purple, while oars of silver beat time to the music of flutes and fifes and harps. She herself lay all along under a canopy of cloth of gold, dressed as Venus in a picture, and beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood on each side to fan her. Her maids were dressed like sea nymphs and graces, some steering at the rudder, some working at the ropes. The perfumes diffused themselves from the vessel to the shore, which was covered with multitudes, part following the galley up the river on either bank, part running out of the city to see the sight. The market-place was quite emptied, and Antony at last was left alone sitting upon the tribunal; while the word went through all the multitude, that Venus was come to feast with Bacchus, for the common good of Asia. On her arrival, Antony sent to invite her to supper. She thought it fitter he should come to her; so, willing to show his good-humour and courtesy, he complied, and went. He found the preparations to receive him magnificent beyond expression, but nothing so admirable as the great number of lights; for on a sudden there was let down altogether so great a number of branches with lights in them so ingeniously disposed, some in squares, and some in circles, that the whole thing was a spectacle that has seldom been equalled for beauty.

Cleopatra and Marc Antony by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

“The next day, Antony invited her to supper, and was very desirous to outdo her as well in magnificence as contrivance; but he found he was altogether beaten in both, and was so well convinced of it that he was himself the first to jest and mock at his poverty of wit and his rustic awkwardness. She, perceiving that his raillery was broad and gross, and savoured more of the soldier than the courtier, rejoined in the same taste, and fell into it at once, without any sort of reluctance or reserve. For her actual beauty, it is said, was not in itself so remarkable that none could be compared with her, or that no one could see her without being struck by it, but the contact of her presence, if you lived with her, was irresistible; the attraction of her person, joining with the charm of her conversation, and the character that attended all she said or did, was something bewitching. It was a pleasure merely to hear the sound of her voice, with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to another; so that there were few of the barbarian nations that she answered by an interpreter; to most of them she spoke herself, as to the Ethiopians, Troglodytes, Hebrews, Arabians, Syrians, Medes, Parthians, and many others, whose language she had learnt; which was all the more surprising because most of the kings, her predecessors, scarcely gave themselves the trouble to acquire the Egyptian tongue, and several of them quite abandoned the Macedonian.

Cleopatra and Marc Antony as Lovers

Cleopatra seemed to be genuinely in love with Antony while Antony some historians say was "enslaved by Cleopatra's seductive powers." He treated her as a monarch of equal stature rather than a subject, much to the dismay of the people of Rome.

Antony and Cleopatra were linked for 11 years. They were together off and on for seven years, with breaks totaling three years in between. Antony was often away on military campaigns. On one campaign he reportedly plundered the famous library at Pergamum to fill the library of Alexandria. Cleopatra bore him twins — a daughter Cleopatra Selene and a son Alexander Helois — and another son Philadelphia Ptolemy.

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: One anecdote recounts Antony’s irritation when Cleopatra witnessed his poor performance at fishing. Having had no luck, Antony secretly ordered a diver to load his hook with fish that had already been caught. After he landed these in quick succession, Cleopatra realized what was going on; she loudly praised Antony’s skill and invited friends to return and admire his ability with rod and line the next day. Unbeknownst to Antony, the queen ordered a diver to put an obviously dead fish on Antony’s hook. Thinking that this time it was a genuine catch, Antony hauled it in to gales of laughter. “General, leave the fishing rod to us poor rulers of Pharos and Canopus,” Cleopatra teased him, “Your prey is cities, kingdoms, and continents.” [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

Cleopatra and Marc Antony as Political Allies

Antony and Cleopatra also formed a strong strategic union. Antony helped Cleopatra kill her last ambitious sibling, her sister Arsinoe, and gave her territory in the Middle East. In return Cleopatra financed Antony's Parthian campaign and his battles against Octavian. Cleopatra chopped down many of the cedar trees in Lebanon to held build up Antony’s navy.

The first couple of Rome used their children to extend their empire. Cleopatra Selene married Juba II, the scholar-king of Mauritania (ruled 25 B.C. to A.D. 23) and author of books on history, art and geography. He brought Greco-Roman culture to his capital of Caesarea and explored the Canary Islands.

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: Antony and Cleopatra had achieved a contented balance between their taste for pleasure and their political responsibilities. However, the spring of 40 B.C. brought news from Rome that shattered the hedonistic idyll of the lovers: Antony’s wife was causing trouble. Fulvia and Antony’s brother had mounted a political challenge to Octavian, who ruled the west from Rome. Naturally, Antony was implicated and it’s likely he had some knowledge and probably gave them his tacit approval. But the conspiracy collapsed, and Antony had to do everything possible to persuade Octavian of his innocence, including returning to Italy. Conveniently, though not suspiciously, Fulvia died that year, and Antony seized the political opportunity. [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

Cleopatra's and Marc Antony's Other Relationships

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: Antony seemed to live a double life, and not just because he was already married with a highly political wife in Rome. There were two sides to his character: The sobriety and gravitas of the Romans and the fun-loving Dionysian spirit of the Greeks. Indeed, Alexandrians said that while he was in the company of Egyptians Antony wore the mask of comedy, but with the Romans he would switch to the mask of tragedy. [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

To prove his loyalty and cement his the alliance with Octavian, Antony married Octavian’s sister, Octavia. She was considered by some to be more beautiful than Cleopatra, but as a model of sober Roman virtue, she was very different from the pleasure-loving Egyptian. Antony finally returned east in 37 B.C. and immediately resumed his passionate affair. He still saw in Cleopatra not only a matchless lover but also a highly efficient ruler, whose political ambitions were attuned with his own. He bolstered her right to rule Egypt, while she supported his belated campaign against the Parthians, a military venture that ended in disaster.

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Whilst he was thus diverting himself and engaged in this boy's play, two despatches arrived; one from Rome, that his brother Lucius and his wife Fulvia, after many quarrels among themselves, had joined in war against Caesar, and having lost all, had fled out of Italy; the other bringing little better news, that Labienus, at the head of the Parthians, was overrunning Asia, from Euphrates and Syria as far as Lydia and Ionia. So, scarcely at last rousing himself from sleep, and shaking off the fumes of wine, he set out to attack the Parthians, and went as far as Phoenicia; but, upon the receipt of lamentable letters from Fulvia, turned his course with two hundred ships to Italy. And, in his way, receiving such of his friends as fled from Italy, he was given to understand that Fulvia was the sole cause of the war, a woman of a restless spirit and very bold, and withal her hopes were that commotions in Italy would force Antony from Cleopatra. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

But it happened that Fulvia as she was coming to meet her husband, fell sick by the way, and died at Sicyon, so that an accommodation was the more easily made. For when he reached Italy, and Caesar showed no intention of laying anything to his charge, and he on his part shifted the blame of everything on Fulvia, those that were friends to them would not suffer that the time should be spent in looking narrowly into the plea, but made a reconciliation first, and then a partition of the empire between them, taking as their boundary the Ionian Sea, the eastern provinces falling to Antony, to Caesar the western, and Africa being left to Lepidus. And an agreement was made that everyone in their turn, as they thought fit, should make their friends consuls, when they did not choose to take the offices themselves.

“These terms were well approved of, but yet it was thought some closer tie would be desirable; and for this, fortune offered occasion. Caesar had an elder sister, not of the whole blood, for Attia was his mother's name, hers Ancharia. This sister, Octavia, he was extremely attached to, as indeed she was, it is said, quite a wonder of a woman. Her husband, Caius Marcellus, had died not long before, and Antony was now a widower by the death of Fulvia; for, though he did not disavow the passion he had for Cleopatra, yet he disowned anything of marriage, reason as yet, upon this point, still maintaining the debate against the charms of the Egyptian. Everybody concurred in promoting this new alliance, fully expecting that with the beauty, honour, and prudence of Octavia, when her company should, as it was certain it would, have engaged his affections, all would be kept in the safe and happy course of friendship. So, both parties being agreed, they went to Rome to celebrate the nuptials, the senate dispensing with the law by which a widow was not permitted to marry till ten months after the death of her husband.

Cleopatra perhaps wasn’t always faithful. There is one story of Cleopatra trying unsuccessfully to seduce Herod of Palestine (the same one who is mentioned in the Bible and built the Temple in Jerusalem) to gain access to his kingdom. After his rebuff she attempted to get Antony to give her part of Herod's kingdom, but he refused because he and Herod were old friends.∵

Extravagance of Cleopatra and Marc Antony

Antony and Cleopatra referred to themselves as Dionysus and Osiris and named their children Sun and Moon. They drank, gambled and fished together — according to unflattering Roman historians anyway — and amused themselves by dressing up as servants and painting the town red and, by one account, planned to start their own club "the Society of Inimitable Lovers."

A grandson of one of Antony and Cleopatra’s cooks told Plutarch the couple used to have a series of banquets prepared for them so if they didn't like the first it was thrown out and they ate the second. While “white breasts showed through Chinese silk” they ate “every delicacy, prompted not by hunger but by a mad live of ostentation...served on golden dishes.” Antony reportedly rubbed Cleopatra's feet at banquets an adopted her custom of using a golden chamber pot.

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: Antony and Cleopatra spent the winter of 41-40 B.C. in Alexandria, reveling in the unique mix of Egyptian and Greek culture for which the city was renowned. They were inseparable companions, playing dice, drinking, and hunting together. The lovers developed a taste for nocturnal escapades, walking the streets dressed as slaves. On one occasion Antony was even jostled and struck in an unsuspecting crowd. They organized lavish banquets for each other. Money was no object for what they called “The society of inimitable livers.” Writing about the reckless extravagance of these banquets, Plutarch described what his grandfather had seen when invited to visit the royal kitchens. The vast quantity of food being prepared, including eight entire roast boars, amazed him. This led him to speculate about the great numbers of guests expected, at which the royal cook burst out laughing. He said that in fact only 12 diners were coming, but they always prepared much more food, as Antony’s appetites were so unpredictable. [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

Cleopatra once bet Marc Anthony she could give the world's most expensive dinner party and drink $500,000 worth for wine without leaving the table. To win the bet she crushed one of her pearl earrings and drank it in a goblet of wine. That one earring was said to worth 100,000 pounds of silver. Pearls (mostly from the Persian Gulf) were so valuable in ancient times that Roman general Vitellus paid for an entire military campaign by selling one of his mother's pearls. Pliny is the source of that tale. This story is generally believed to be apocryphal, but some believe there may be some truth to it. But, while Antony and Cleopatra were enjoying themselves, Octavian was building up his army and navy and preparing for a fight.

Antony Becomes Wasteful and Negligent

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Antony was so captivated by her that, while Fulvia his wife maintained his quarrels in Rome against Caesar by actual force of arms, and the Parthian troops, commanded by Labienus (the king's generals having made him commander-in-chief), were assembled in Mesopotamia, and ready to enter Syria, he could yet suffer himself to be carried away by her to Alexandria, there to keep holiday, like a boy, in play and diversion, squandering and fooling away in enjoyments that most costly, as Antiphon says, of all valuables, time. They had a sort of company, to which they gave a particular name, calling it that of the Inimitable Livers. The members entertained one another daily in turn, with all extravagance of expenditure beyond measure or belief. Philotas, a physician of Amphissa, who was at that time a student of medicine in Alexandria, used to tell my grandfather Lamprias that, having some acquaintance with one of the royal cooks, he was invited by him, being a young man, to come and see the sumptuous preparations for supper. So he was taken into the kitchen, where he admired the prodigious variety of all things; but particularly, seeing eight wild boars roasting whole, says he, "Surely you have a great number of guests." The cook laughed at his simplicity, and told him there were not above twelve to sup, but that every dish was to be served up just roasted to a turn, and if anything was but one minute ill-timed, it was spoiled; "And," said he, "maybe Antony will sup just now, maybe not this hour, maybe he will call for wine, or begin to talk, and will put it off. So that," he continued, "it is not one, but many suppers must be had in readiness, as it is impossible to guess at his hour." [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

This was Philotas's story; who related besides, that he afterwards came to be one the medical attendants of Antony's eldest son by Fulvia, and used to be invited pretty often, among other companions, to his table, when he was not supping with his father. One day another physician had talked loudly, and given great disturbance to the company, whose mouth Philotas stopped with this sophistical syllogism: "In some states of fever the patient should take cold water; every one who has a fever is in some state of fever; therefore in a fever cold water should always be taken." The man was quite struck dumb, and Antony's son, very much pleased, laughed aloud, and said, "Philotas, I make you a present of all you see there," pointing to a sideboard covered with plate. Philotas thanked him much, but was far enough from ever imagining that a boy of his age could dispose of things of that value. Soon after, however, the plate was all brought to him, and he was desired to get his mark upon it; and when he put it away from him, and was afraid to accept the present. "What ails the man?" said he that brought it; "do you know that he who gives you this is Antony's son, who is free to give it, if it were all gold? but if you will be advised by me, I would counsel you to accept of the value in money from us; for there may be amongst the rest some antique or famous piece of workmanship, which Antony would be sorry to part with." These anecdotes, my grandfather told us, Philotas used frequently to relate.

Cleopatra's Banquet

“To return to Cleopatra; Plato admits four sorts of flattery, but she had a thousand. Were Antony serious or disposed to mirth, she had at any moment some new delight or charm to meet his wishes; at every turn she was upon him, and let him escape her neither by day nor by night. She played at dice with him, drank with him, hunted with him; and when he exercised in arms, she was there to see. At night she would go rambling with him to disturb and torment people at their doors and windows, dressed like a servant-woman, for Antony also went in servant's disguise, and from these expeditions he often came home very scurvily answered, and sometimes even beaten severely, though most people guessed who it was. However, the Alexandrians in general liked it all well enough, and joined good-humouredly and kindly in his frolic and play, saying they were much obliged to Antony for acting his tragic parts at Rome, and keeping comedy for them. It would be trifling without end to be particular in his follies, but his fishing must not be forgotten. He went out one day to angle with Cleopatra, and, being so unfortunate as to catch nothing in the presence of his mistress, he gave secret orders to the fishermen to dive under water, and put fishes that had been already taken upon his hooks; and these he drew so fast that the Egyptian perceived it. But, feigning great admiration, she told everybody how dexterous Antony was, and invited them next day to come and see him again. So, when a number of them had come on board the fishing-boats, as soon as he had let down his hook, one of her servants was beforehand with his divers and fixed upon his hook a salted fish from Pontus. Antony, feeling his line give, drew up the prey, and when, as may be imagined, great laughter ensued, "Leave," said Cleopatra, "the fishing-rod, general, to us poor sovereigns of Pharos and Canopus; your game is cities, provinces, and kingdoms."

Events in Rome

In Rome, Octavian viewed Antony and Cleopatra's activities with disgust and began to maneuver against them.Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: ““Sextus Pompeius was in possession of Sicily, and with his ships, under the command of Menas, the pirate, and Menecrates, so infested the Italian coast that no vessels durst venture into those seas. Sextus had behaved with much humanity towards Antony, having received his mother when she fled with Fulvia, and it was therefore judged fit that he also should be received into the peace. They met near the promontory of Misenum, by the mole of the port, Pompey having his fleet at anchor close by, and Antony and Caesar their troops drawn up all along the shore. There it was concluded that Sextus should quietly enjoy the government of Sicily and Sardinia, he conditioning to scour the seas of all pirates, and to send so much corn every year to Rome. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra and Richard Burton as Marc Antony in the 1963 film Cleopatra

“This agreed on, they invited one another to supper, and by lot it fell to Pompey's turn to give the first entertainment, and Antony, asking where it was to be, "There," said he, pointing to the admiral-galley, a ship of six banks of oars. "that is the only house that Pompey is heir to of his father's." And this he said, reflecting upon Antony, who was then in possession of his father's house. Having fixed the ship on her anchors, and formed a bridgeway from the promontory to conduct on board of her, he gave them a cordial welcome. And when they began to grow warm, and jests were passing freely on Antony and Cleopatra's loves, Menas, the pirate, whispered Pompey, in the ear, "Shall I," said he, "cut the cables and make you master not of Sicily only and Sardinia, but of the whole Roman empire?" Pompey, having considered a little while, returned him answer, "Menas, this might have been done without acquainting me; now we must rest content; I do not break my word." And so, having been entertained by the other two in their turns, he set sail for Sicily.

Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: Tensions grew between the former allies and then erupted into a war that Octavian presented as a struggle against a dissolute Egyptian queen into whose clutches Antony had fallen. The armies of the Roman rivals met in Greece, where Octavian managed to cut Antony’s supply lines to Egypt. Forced into action, Antony took Cleopatra’s advice to fight at sea. In 31 B.C. about 900 ships clashed at the Battle of Actium. It was a closely fought engagement. But when Cleopatra’s galleys fled Antony followed, and his forces soon surrendered. The lovers were defeated, and in a dramatic fashion, both took their own lives. Mark Antony’s death removed the last obstacle to Octavian becoming sole emperor of Rome. He assumed the title Augustus in 27 B.C. [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024