Home | Category: Age of Caesar / Age of Augustus

ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR

In 44 B.C., after declaring himself “Dictator for Life”, Caesar was crowned with a royal diadem at a religious ceremony, ushering in the era of imperial Rome. Many Romans were appalled by Caesar's audacious seizure of power and riled further when he placed a statue with his likeness next to statues of the founders of Rome. Almost immediately members of the Senate began plotting against him.

On the ides of March (March 15, 44, B.C.), a month after he proclaimed himself Dictator for Life, 55-year-old Caesar was assassinated on the floor of the Senate by Brutus and Cassius, an event recounted in a famous Shakespeare play.

The assassination was at least in part a display of contempt against Caesar’s ruthless impoundment of power and rumors that he was planning to rule the Roman Empire with Cleopatra from Alexandria. Brutus, a close friend of Caesar, and Cassius, the mastermind of the conspiracy, recruited 20 Senators and 40 other conspirators, including many people who had been loyal to Caesar. They ones that planned to participate in the killing carried daggers concealed under their cloaks.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, FAMILY, SOURCES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MARC ANTONY: HIS LIFE, RELATIONS WITH CAESAR AND MILITARY CAMPAIGNS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO'S MURDER, EVENTS AFTER CAESARS'S DEATH AND THE END OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.): LOOKS, SEX LIFE, FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA AND MARC ANTONY: ROMANCE, EVENTS, EXTRAVAGANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF ACTIUM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND DEATHS OF ANTONY, CLEOPATRA AND THEIR CHILDREN europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Roman Revolution” by Ronald Syme (1939) Amazon.com

“The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome” by Michael Parenti Amazon.com;

“The Ides: Caesar's Murder and the War for Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2010) Amazon.com;

“Octavian: Rise to Power: The Early Years of Caesar” by Patrick J. Parrelli (2015) Amazon.com;

“Augustus: First Emperor of Rome” by Adrian Goldsworthy (Yale University Press, 2014); Amazon.com;

"A Noble Ruin: Mark Antony, Civil War, and the Collapse of the Roman Republic"

by W. Jeffrey Tatum Amazon.com

“Mark Antony: A Life” by Patricia Southern (2012) Amazon.com;

“Mutina 43 BC: Mark Antony's Struggle for Survival” by Nic Fields, Peter Dennis (Illustrator) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium” by Barry S. Strauss (2022) Amazon.com

“Cleopatra and Antony” by Diana Preston, Amazon.com;

“Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2010) Amazon.com;

“Julius Caesar: The Life and Times of the People’s Dictator” by Luciano Canfora, Stuart Midgley Marian Hill (2007) Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny” by Edward Watts (2020), Illustrated Amazon.com;

“The Fall of the Roman Republic: Roman History, Books 36-40 (Oxford World's Classics)

by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

“Fall of the Roman Republic (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch Amazon.com;

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics Hardcover) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republics” by Harriet I. Flower (2009) Amazon.com

After Caesar’s Assassination

After the murder Caesar's onetime ally Marc Anthony, went to the Roman Forum "to bury Caesar, not to praise him." Brutus attempted to give a speech at the Forum and was shouted down and then was forced to barricade himself and other conspirators at the Capitol. Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “When Cæsar was dispatched, Brutus stood forth to give a reason for what they had done, but the senate would not hear him, but flew out of doors in all haste, and filled the people with so much alarm and distraction, that some shut up their houses, others left their counters and shops. All ran one way or the other, some to the place to see the sad spectacle, others back again after they had seen it. Antony and Lepidus, Cæsar’s most faithful friends, got off privately, and hid themselves in some friends’ houses. Brutus and his followers, being yet hot from the deed, marched in a body from the senate-house to the capitol with their drawn swords, not like persons who thought of escaping, but with an air of confidence and assurance, and as they went along, called to the people to resume their liberty, and invited the company of any more distinguished people whom they met. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“And some of these joined the procession and went up along with them, as if they also had been of the conspiracy, and could claim a share in the honor of what had been done. As, for example, Caius Octavius and Lentulus Spinther, who suffered afterwards for their vanity, being taken off by Antony and the young Cæsar, and lost the honor they desired, as well as their lives, which it cost them, since no one believed they had any share in the action. For neither did those who punished them profess to revenge the fact, but the ill-will. The day after, Brutus with the rest came down from the capitol, and made a speech to the people, who listened without expressing either any pleasure or resentment, but showed by their silence that they pitied Cæsar, and respected Brutus. The senate passed acts of oblivion for what was past, and took measures to reconcile all parties. They ordered that Cæsar should be worshipped as a divinity, and nothing, even of the slightest consequence, should be revoked, which he had enacted during his government. At the same time they gave Brutus and his followers the command of provinces, and other considerable posts. So that all people now thought things were well settled, and brought to the happiest adjustment.

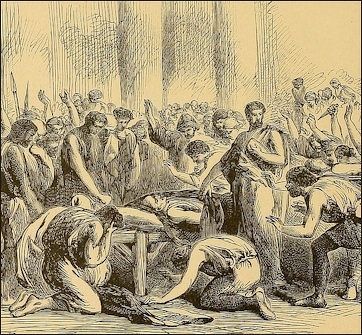

Caesar carried out of the Senate

“But when Cæsar’s will was opened, and it was found that he had left a considerable legacy to each one of the Roman citizens, and when his body was seen carried through the market-place all mangled with wounds, the multitude could no longer contain themselves within the bounds of tranquillity and order, but heaped together a pile of benches, bars, and tables, which they placed the corpse on, and setting fire to it, burnt it on them. Then they took brands from the pile, and ran some to fire the houses of the conspirators, others up and down the city, to find out the men and tear them to pieces, but met, however, with none of them, they having taken effectual care to secure themselves.”

In the account of the assassination from Brutus’s biography, Plutarch wrote: “Caesar being thus slain, Brutus, stepping forth into the midst, intended to have made a speech, and called back and encouraged the senators to stay; but they all affrighted ran away in great disorder, and there was a great confusion and press at the door, though none pursued or followed. For they had come to an express resolution to kill nobody beside Caesar, but to call and invite all the rest to liberty. It was indeed the opinion of all the others, when they consulted about the execution of their design, that it was necessary to cut off Antony with Caesar, looking upon him as an insolent man, an affecter of monarchy, and one that, by his familiar intercourse, had gained a powerful interest with the soldiers. And this they urged the rather, because at that time to the natural loftiness and ambition of his temper there was added the dignity of being counsel and colleague to Caesar. But Brutus opposed this consul, insisting first upon the injustice of it, and afterwards giving them hopes that a change might be worked in Antony. For he did not despair but that so highly gifted and honourable a man, and such a lover of glory as Antony, stirred up with emulation of their great attempt, might, if Caesar were once removed, lay hold of the occasion to be joint restorer with them of the liberty of his country. Thus did Brutus save Antony's life. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), The Assassination of Julius Caesar, from Marcus Brutus, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

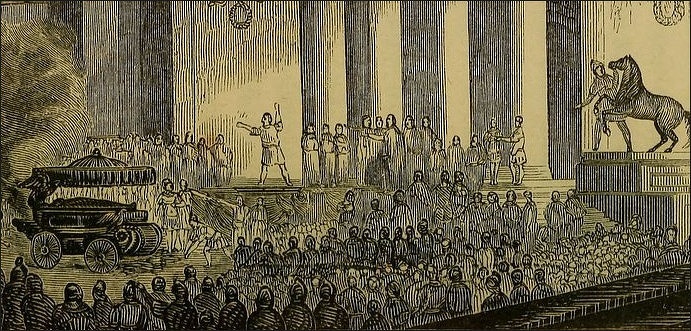

Caesar’s Funeral

Suetonius wrote: “When the funeral was announced, a pyre was erected in the Campus Martius near the tomb of Julia, and on the rostra a gilded shrine was placed, made after the model of the temple of Venus Genetrix; within was a couch of ivory with coverlets of purple and gold, and at its head a pillar hung with the robe in which he was slain. Since it was clear that the day would not be long enough for those who offered gifts, they were directed to bring them to the Campus by whatsoever streets of the city they wished, regardless of any order of precedence. At the funeral games, to rouse pity and indignation at his death, these words from the Armorum of Pacuvius were sung: — - 'Saved I these men that they might murder me?" and words of a like purport from the Electra of Atilius. Instead of a eulogy the consul Antonius caused a herald to recite the decree of the Senate in which it had voted Caesar all divine and human honors at once, and likewise the oath with which they had all pledged themselves to watch over his personal safety; to which he added a very few words of his own.

The bier on the rostra was carried down into the Forum by magistrates and ex-magistrates; and while some were urging that it be burned in the temple of Jupiter of the Capitol, and others in the Curia of Pompeius, on a sudden two beings [cf. the apparition at the Rubicon] with swords by their sides and brandishing a pair of darts set fire to it with blazing torches, and at once the throng of bystanders heaped upon it dry branches, the judgment seats with the benches, and whatever else could serve as an offering. Then the musicians and actors tore off their robes, which they had taken from the equipment of his triumphs and put on for the occasion, rent them to bits and threw them into the flames, and the veterans of the legions the arms with which they had adorned themselves for the funeral; many of the women too, offered up the jewels which they wore and the amulets and robes of their children. At the height of the public grief a throng of foreigners went about lamenting each after the fashion of his country, above all the Jews, who even flocked to the place for several successive nights. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

Caesar's funeral

“Immediately after the funeral the people ran to the houses of Brutus and Cassius with firebrands, and after being repelled with difficulty, they slew Helvius Cinna when they met him, through a mistake in the name, supposing that he was Cornelius Cinna, who had the day before made a bitter indictment of Caesar and for whom they were looking; and they set his head upon a spear and paraded it about the streets. Afterwards they set up in the Forum a solid column of Numidian marble almost twenty feet high, and inscribed upon it, "To the Father of his Country." At the foot of this they continued for a long time to sacrifice, make vows, and settle some of their disputes by an oath in the name of Caesar.

“Caesar left in the minds of some of his friends the suspicion that he did not wish to live longer and had taken no precautions, because of his failing health; and that therefore he neglected the warnings which came to him from portents and from the reports of his friends. Some think that it was because he had full trust in that last decree of the senators and their oath that he dismissed even the armed bodyguard of Hispanic soldiers that formerly attended him. Others, on the contrary, believe that he elected to expose himself once for all to the plots that threatened him on every hand, rather than to be always anxious and on his guard. Some, too, say that he was wont to declare that it was not so much to his own interest as to that of his country that he remain alive; he had long since had his fill of power and glory; but if aught befell him, the Republic would have no peace, but would be plunged in civil strife under much worse conditions.

“About one thing almost all are fully agreed, that he all but desired such a death as he met; for once when he read in Xenophon [Cyropedeia, 8.7] how Cyrus in his last illness gave directions for his funeral, he expressed his horror of such a lingering kind of end and his wish for one which was swift and sudden. And the day before his murder, in a conversation which arose at a dinner at the house of Marcus Lepidus, as to what manner of death was most to be desired, he had given his preference to one which was sudden and unexpected.

“He died in the fifty-sixth year of his age, and was numbered among the gods, not only by a formal decree, but also in the conviction of the common people. For at the first of the games which his heir Augustus gave in honor of his apotheosis, a comet shone for seven successive days, rising about the eleventh hour [about an hour before sunset] and was believed to be the soul of Caesar, who had been taken to heaven; and this is why a star is set upon the crown of his head in his statue. It was voted that the curia in which he was slain be walled up, that the Ides of March be called the Day of Parricide, and that a meeting of the senate should never be called on that day. Hardly any of his assassins survived him for more than three years, or died a natural death. They were all condemned, and they perished in various ways — some by shipwreck, some in battle; some took their own lives with the self-same dagger with which they had impiously slain Caesar.

Fate of Cassius and Brutus

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”:“One Cinna, a friend of Cæsar’s, chanced the night before to have an odd dream. He fancied that Cæsar invited him to supper, and that upon his refusal to go with him, Cæsar took him by the hand and forced him, though he hung back. Upon hearing the report that Cæsar’s body was burning in the market-place, he got up and went thither, out of respect to his memory, though his dream gave him some ill apprehensions, and though he was suffering from a fever. One of the crowd who saw him there, asked another who that was, and having learned his name, told it to his next neighbor. It presently passed for a certainty that he was one of Cæsar’s murderers, as, indeed, there was another Cinna, a conspirator, and they, taking this to be the man, immediately seized him, and tore him limb from limb upon the spot. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

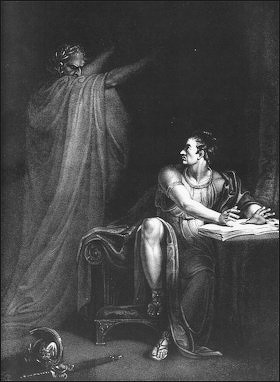

Caesar's ghost appears to Brutus in the Shakespeare play

“Brutus and Cassius, frightened at this, within a few days retired out of the city. What they afterwards did and suffered, and how they died, is written in the Life of Brutus. Cæsar died in his fifty-sixth year, not having survived Pompey above four years. That empire and power which he had pursued through the whole course of his life with so much hazard, he did at last with much difficulty compass, but reaped no other fruits from it than the empty name and invidious glory. But the great genius which attended him through his lifetime, even after his death remained as the avenger of his murder, pursuing through every sea and land all those who were concerned in it, and suffering none to escape, but reaching all who in any sort or kind were either actually engaged in the fact, or by their counsels any way promoted it.

“The most remarkable of mere human coincidences was that which befell Cassius, who, when he was defeated at Philippi, killed himself with the same dagger which he had made use of against Cæsar. The most signal preter-natural appearances were the great comet, which shone very bright for seven nights after Cæsar’s death, and then disappeared, and the dimness of the sun,* whose orb continued pale and dull for the whole of that year, never showing its ordinary radiance at its rising, and giving but a weak and feeble heat. The air consequently was damp and gross, for want of stronger rays to open and rarify it. The fruits, for that reason, never properly ripened, and began to wither and fall off for want of heat, before they were fully formed. But above all, the phantom which appeared to Brutus showed the murder was not pleasing to the gods. The story of it is this.

“Brutus being to pass his army from Abydos to the continent on the other side, laid himself down one night, as he used to do, in his tent, and was not asleep, but thinking of his affairs, and what events he might expect. For he is related to have been the least inclined to sleep of all men who have commanded armies, and to have had the greatest natural capacity for continuing awake, and employing himself without need of rest. He thought he heard a noise at the door of his tent, and looking that way, by the light of his lamp, which was almost out, saw a terrible figure, like that of a man, but of unusual stature and severe countenance. He was somewhat frightened at first, but seeing it neither did nor spoke any thing to him, only stood silently by his bed-side, he asked who it was. The spectre answered him, “Thy evil genius, Brutus, thou shalt see me at Philippi.” Brutus answered courageously, “Well, I shall see you,” and immediately the appearance vanished. When the time was come, he drew up his army near Philippi against Antony and Cæsar, and in the first battle won the day, routed the enemy, and plundered Cæsar’s camp. The night before the second battle, the same phantom appeared to him again, but spoke not a word. He presently understood his destiny was at hand, and exposed himself to all the danger of the battle. Yet he did not die in the fight, but seeing his men defeated, got up to the top of a rock, and there presenting his sword to his naked breast, and assisted, as they say, by a friend, who helped him to give the thrust, met his death.”

Rome after Caesar’s Death

Brutus, Cassius and men who murdered and conspired against Caesar considered themselves as “liberators” of the republic. Whatever may have been their motives, they seem to have taken little thought as to how Rome would be governed after they had killed Caesar. If they thought that the senate would take up the powers it had lost, and successfully rule the republic, they were grievously mistaken. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The only leading man of the senate who had survived the last civil war was Cicero; but Cicero with all his learning and eloquence could not take the place of Caesar. What Rome needed was what the liberators had taken from her, a master mind of broad views and of great executive power. It is no surprise that the death of Caesar was followed by confusion and dismay. No one knew which way to look or what to expect.\~\

Soon there appeared new actors upon the scene, men struggling for the supreme power in the state—M. Antonius (Antony), the friend of Caesar and his fellow-consul; C. Octavian, his adopted son and heir; M. Aemilius Lepidus, his master of horse; Sextus Pompeius, his previous enemy and the son of his greatest rival; while Cicero still raised his voice in defense of what he regarded as his country’s freedom. \~\

Initial Limited Political Fallout After Caesar’s Death

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Cicero approved of the result if not the method” of Caesar’s death;” he says repeatedly in his letters that the Ides of March was a glorious day. Cicero had encouraged the assassins to their deed on the Ides of March, but neither he nor they had a plan for restoring the Republic afterwards. Having allowed Antony to regain the initiative, Cicero retired to his villa at Puteoli in the spring of 44. There are surviving over 200 letters written by Cicero between the Ides of March and his own death; thus there is a nearly unique opportunity for constructing a detailed account of the politics of the day. Cicero put forward no clear political or military solutions in the aftermath of the Ides; instead, he wrung his hands over the situation and hoped that someone else would take the lead. Is Cicero to blame for his indecision in these months, or was he simply being cautious and prudent, waiting for a better opportunity and greater chances of success? [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Lepidus, Antony and Octavian

“Surprisingly, Caesar's death did not lead to a quick renunciation of his acts or massive retaliation against his supporters. Cicero supported amnesty for the conspirators; The conspirators had not looked far beyond the tyrannicide, nor severed all of the hydra's heads. The second- and third-in-command in Caesar's organization were his magister equitum M. Aemilius Lepidus and his co-consul for 44, M. Antonius (Mark Antony). Cassius had proposed that Antony should be killed along with Caesar, but Brutus had prevailed with his opinion that Antony might live. Cicero's letters to Atticus from April of 44 give a sense of the uncertainty of the political situation. Anthony was rumoured to be hoarding grain in the capital, but for what purpose was not known; ^*^

“Antony managed to effect a rapid deal, brokered by Cicero, with the Republicans: there was to be amnesty for Caesar's killers, but his acts were to be upheld. Why did Brutus and Cassius agree to this compromise, which seems to undercut the purpose of their deed? The answer is military power; the conspirators could kill the dictator, but they could not change the fact that Antony had lost no time in bringing some of Lepidus' legions from Spain and Gallia Narbonensis (S. France). Nor did Antony intend to let go the reins of power. At the funeral oration for Caesar, he surprised his erstwhile Republican "allies" by igniting the wrath of the crowd against the tyrannicides; Brutus and Cassius were forced to flee from Italy, but they fled not into oblivion. Already assigned to safeguard the corn supply from Libya and Egypt, they made for the more fertile recruiting grounds of Macedonia, Asia, and Syria. In fact this episode was a deliberate attempt by Antony to consolidate his position as the successor of Julius Caesar (Plut. Cicero 42 over Suet. Iul. 84). It is true that Caesar managed to curry favor with the people even after his death by leaving 300 sesterces to every Roman citizen. However, there is a further reason why the historical record represented the event as a popular uprising against the murderers of Caesar, that it was consistent with Octavian's later claim to have been carrying out the popular will in avenging the death of Caesar.” ^*^

Second Triumverate with Octavian and Marc Antony

After Caesar's assassination in 44 B.C., Octavian's connection to Caesar boosted him on the political scene. At that time Octavian (the future Augustus) was seen as a “deceptively, malleable-seeming” 18-year-old. “He is wholely devoted to me," Cicero boasted, not long before the youth cut a deal to have him murdered. Octavian joined with Antony and Lepidus to form a Triumvirate (“Group of Three). Octavian was able get Caesar's old soldiers behind him and win the support of the Senate.

The Triumvirate battled Cassius and Brutus for control of Rome during five years of civil war. After defeating the armies of Brutus and Cassius at the Battle of Phillipi in 42 B.C., Lepidus was stripped of his power and Octavian and Marc Antony divided the empire, with Octavian getting Italy and the west and Antony getting the east.

According to National Geographic The year after Caesar’s death, in 43 B.C., Octavian, Caesar’s great-nephew and protégé, formed the Second Triumverate with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, a Roman general and statesman, and Mark Antony, a Roman general under Caesar, proclaiming they were “settling the Republic.” It would prove an uneasy alliance in the long term — one that in the end would leave one man standing. But at first, the triumvirate worked together to make and veto laws to their benefit, appoint governors and consuls, and decide judicial cases without appeal, even though the Senate and assemblies still met and elections continued. [Source: National Geographic History, August 24, 2022]

In one of their most atrocious acts, they put to death and confiscated the property of some 3,000 patricians, including Cicero, who openly rebuked the triumvirate. The great Roman philosopher was an out-spoken critic of Antony, and upon his death, Antony’s wife, Fulvia, took Cicero’s severed head, spat on it, and jabbed his tongue repeatedly with her hairpin, taking postmortem revenge against the famous orator.

The triumvirate faced constant threats to their power, including one from the exiled conspirators behind Caesar’s assassination, Brutus and Cassius, who raised an army to overthrow the trio. Antony beat them at Philippi in 42 B.C., absorbing their forces into his own and taking control of Rome’s eastern territories. Believing that Antony deserved to be sole ruler, his wife, Fulvia, and brother, Lucius, mounted a civil war that was put down by Octavian. Tensions rose between the triumvirs. Meantime, Pompey’s son Sextus, who upheld the cause of his father against Julius Caesar, corralled naval fleets that attacked the triumvirate’s forces in a series of confronta-tions off the coast of Italy. After beating Sextus, Lepidus demanded more than a third of the credit and more power and prestige. Octavian maneuvered him out of power, leaving Antony his sole opponent. [Source: National Geographic History, August 24, 2022]

Mark Anthony and Octavian, shared power for ten years until Octavian declared war on Antony's lover's Cleopatra. While Antony and Cleopatra were enjoying themselves, Octavian was building up his army and navy and preparing for a fight.

Caesar’s Legacy

According to National Geographic: Though he was violently deposed, Caesar’s brief rule spelled the end of an era. The republican government would be replaced by a succession of totalitarian emperors: The Roman Empire was officially born. But first, it needed a leader. It would take 13 long years and a series of desperate power struggles before the Roman Republic finally tumbled and the final candidate for emperor donned his triumphal toga. [Source: National Geographic History, August 24, 2022]

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”:“It is commonly said that public bodies are most insulting and contumelious to a good man, when they are puffed up with prosperity and success. But the contrary often happens; afflictions and public calamities naturally imbittering and souring the minds and tempers of men, and disposing them to such peevishness and irritability, that hardly any word or sentiment of common vigor can be addressed to them, but they will be apt to take offence. He that remonstrates with them on their errors, is presumed to be insulting over their misfortunes, and any free spoken expostulation is construed into contempt. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Honey itself is searching in sore and ulcerated parts; and the wisest and most judicious counsels prove provoking to distempered minds, unless offered with those soothing and compliant approaches which made the poet, for instance, characterize agreeable things in general, by a word expressive of a grateful and easy touch,* exciting nothing of offence or resistance. Inflamed eyes require a retreat into dusky places, amongst colors of the deepest shades, and are unable to endure the brilliancy of light. So fares it in the body politic, in times of distress and humiliation; a certain sensitiveness and soreness of humor prevail, with a weak incapacity of enduring any free and open advice, even when the necessity of affairs most requires such plaindealing, and when the consequences of any single error may be beyond retrieving. At such times the conduct of public affairs is on all hands most hazardous. Those who humor the people are swallowed up in the common ruin; those who endeavor to lead them aright, perish the first in their attempt.

“Astronomers tell us, the sun’s motion is neither exactly parallel with that of the heavens in general, nor yet directly and diametrically opposite, but describing an oblique line, with insensible declination he steers his course in such a gentle, easy curve, as to dispense his light and influence, in his annual revolution, at several seasons, in just proportions to the whole creation. So it happens in political affairs; if the motions of rulers be constantly opposite and cross to the tempers and inclination of the people, they will be resented as arbitrary and harsh; as, on the other side, too much deference, or encouragement, as too often it has been, to popular faults and errors, is full of danger and ruinous consequences. But where concession is the response to willing obedience, and a statesman gratifies his people, that he may the more imperatively recall them to a sense of the common interest, then, indeed, human beings, who are ready enough to serve well and submit to much, if they are not always ordered about and roughly handled, like slaves, may be said to be guided and governed upon the method that leads to safety. Though it must be confessed, it is a nice point and extremely difficult, so to temper this lenity as to preserve the authority of the government. But if such a blessed mixture and temperament may be obtained, it seems to be of all concords and harmonies the most concordant and most harmonious. For thus we are taught even God governs the world, not by irresistible force, but persuasive argument and reason, controlling it into compliance with his eternal purposes.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except last picture Live Science

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024