Home | Category: Philosophy

PLATO AND SOME OF HIS MAIN IDEAS

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 3679, with parts of Plato's Republic

Plato (427?-347 B.C.) was one of the world's most influential philosophers. A student of Socrates and a teacher of Aristotle, he is regarded as an idealist who explored justice and virtue in postwar Athens and founded the Academy. He and his philosophy gave birth to the concept of Platonic love, and the legend of Atlantis. Alfred North Whitehead said: “The safest general characterization of the whole Western philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”

Plato accommodated different viewpoints by saying they could coexist on different levels in his Theory of Forms (sometimes translated as Theory of Ideas). The most famous illustration of this was in his “Parable of the Cave” ("Allegory of the Cave") in “The Republic” in which he argued there was a permanent world that could not be perceives and a shadow world that was always changing.

Plato denounced the material world and the pleasures of the flesh, which is one reason why he was popular among Christian theologians. Plato wrote: "Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy...cities will never cease from ill, nor the human race." He also once wrote democracy is a "delightful form of government, anarchic and motley."

For, while Plato elaborated to a high degree the faculty by which the abstract is understood and presented, he was Greek enough to follow the artistic instinct in teaching by means of a clear-cut concrete type of philosophical excellence. The use of the myth in the dialogues has occasioned considerable difficulty to the commentators and critics. When we try to put a value on the content of a Platonic myth, we are often baffled by the suspicion that it is all meant to be subtly ironical, or that it is introduced to cover up the inherent contradictions of Plato's thought. In any case, the myth should never be taken too seriously or invoked as an evidence of what Plato really believed. [Source: Catholic Encyclopedia Article, 1913]

RELATED ARTICLES:

PLATO: HIS LIFE, ACADEMY AND DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SOCRATES' LIFE, CHARACTER, STUDENTS AND PLATO europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PLATO’S PHILOSOPHY AND VIEWS ON ETHICS, SCIENCE AND LOVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK PHILOSOPHY: HISTORY, PHILOSOPHERS, MAJOR SCHOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Plato’s Account of Socrates See SOCRATES'S PHILOSOPHIES, IDEAS, DISCUSSIONS AND THE SOCRATIC METHOD europe.factsanddetails.com

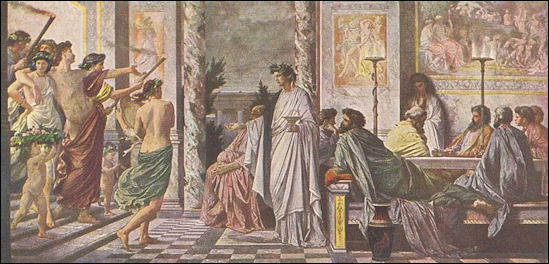

Plato’s Account of Socrates at the Symposia See SOCRATES AT A SYMPOSIA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Plato’s Account of Socrates’ Death See SOCRATES' TRIAL, DEFENSE AND DEATH Europe. factsanddetails.com

ATLANTIS: PLATO, LEGENDS AND THE SEACH FOR IT europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Plato: Complete Works” by Plato , John M. Cooper, et al. (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Trial and Death of Socrates” by Plato , John M. Cooper , et al. (2000) Amazon.com;

“Symposium (Oxford World's Classics) by Plato Amazon.com;

“Republic” by Plato translated by Allan Bloom (2011) Amazon.com;

“Plato: Five Dialogues: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo (Hackett Classics)

by Plato, translated by John M. Cooper, et al. (2002) Amazon.com;

“Timaeus and Critias” (Penguin Classics), includes account of the rise and fall of Atlantis, by Plato, Thomas Kjeller Johansen, et al. (2008) Amazon.com;

“Plato: The Man and His Work” by A. E. Taylor (2011) Amazon.com;

“Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy” by Robin Waterfield (2023) Amazon.com;

“Plato's Academy Annotated Edition” by Paul Kalligas Amazon.com;

“The Sophists” (Reprint Edition) by W. K. C. Guthrie (1906-1981) Amazon.com;

“Conversations of Socrates” (Penguin Classics) by Xenophon , Robin H. Waterfield , et al. Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Philosophers” by Editors of Canterbury Classics (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Philosophy: Thales to Aristotle (Readings in the History of Philosophy) by Reginald E. Allen (1991) Amazon.com;

“Greek Thought: A Guide to Classical Knowledge” by Jacques Brunschwig and Geoffrey E.R. Lloyd (Harvard University Press) Amazon.com;

“The Seekers” by Daniel Boorstin (1998) Amazon.com;

Plato's Works

Plato left behind a great number of written works, many of which were in the form of dialogues in which Socrates is the leader of the discussions conducted in a Socratic question-and-answer style. In many of Plato’s works Socrates is a mouthpiece for Plato’s ideas and doctrines. Many of are written in a poetic language with the use of metaphors, parables and symbols.

When or why Plato wrote his dialogue is not known. His most famous works include “The Laws” ; “The Republic” , an outline for an ideal government; “Symposiums” , featuring guests sitting around a banquets discussing ideal love and beauty: “ Apology” , a compelling portrait and defense of Socrates; and “ Timaeus” , a discussion on the nature of the universe.

Allegory of the Cave

“It is practically certain that all Plato's genuine works have come down to us. The lost works ascribed to him, such as the "Divisions" and the "Unwritten Doctrines", are certainly not genuine. Of the thirty-six dialogues, some — the "Phaedrus", "Protagoras", "Phaedo", "The Republic", "The Banquet", etc. — are undoubtedly genuine; others — e.g. the "Minos", — may with equal certainty be considered spurious; while still a third group — the "Ion", "Greater Hippias", and "First Alcibiades" — is of doubtful authenticity. In all his writings, Plato uses the dialogue with a skill never since equalled. That form permitted him to develop the Socratic method of question and answer. [Source: Catholic Encyclopedia Article, 1913]

Plato’s most famous works and their English translators:

“The Apology”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Euthyphro”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Meno”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Parmenides”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Phaedo”, translated by Harold North Fowler,

another version translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Phaedrus”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Republic”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Seventh Letter”, translated by J. Harwood

“The Symposium”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

“The Theaetetus”, translated by Benjamin Jowett

[Source: available online through Evansville University] |=|

Links to Plato's Works

Plato (427-347 B.C.)

2ND Plato, Academy IEP iep.utm.edu/plato

2ND Plato and Platonism, Catholic Encyclopedia newadvent.org

WEB Classics Archive: Plato MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

The Apology Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; Socrates' life

The Meno Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; - theory of learning by anamnesis/recollection

The Gorgias Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

The Symposium Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; -theory of love

The Crito Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

The Phaedo Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; - theoy of forms/ideas

The Phaedrus Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

The Timeaus MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

The Republic Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; - theory of forms/ideas, the ideal state

The Republic MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

See 2ND Study Guide Brooklyn College, Internet Archive web.archive.org;

(ps.-?) Plato: Seventh Letter: To the Relatives and Friends of Dion, UPenn, Internet Archive web.archive.org, Excerpts for teaching

The Republic, excerpts Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu, On the Philosopher-king

The Cave Internet Archive web.archive.org;

On Atlantis from The Timaeus Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

The Timeaus Internet Archive web.archive.org, Origin of the Atlantis myth.

Parable of the Cave

Plato gave a great deal of thought to the natural world and how it functions. Karen Carr wrote in History for Kids He thought that everything had a sort of ideal form, like the idea of a chair. Then an actual chair was a sort of poor imitation of the ideal chair that exists only in your mind. One of the ways Plato tried to explain his ideas was with the famous metaphor of the cave. [Source: Karen Carr, History for Kids]

The “ Parable of the Cave” begins: “Behold! Human beings living in an underground den, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by chains from turning around their heads. Above and behind them is a fire blazing at a distance, and the fire and the prisoners there is a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen, which marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets.”

“Suppose now that one of the men escaped, and got out of the cave, and saw what real people looked like, and real trees and grass. If he went back to the cave and told the other men what he had seen, would they believe him, or would they think he was crazy? Plato says that we are like those men sitting in the cave: we think we understand the real world, but because we are trapped in our bodies we can see only the shadows on the wall. One of his goals is to help us understand the real world better, by finding ways to predict or understand the real world even without being able to see it. Today we might call that real world the world of pure mathematics or physics.

Plato argued that real world was the one that couldn’t be perceived and the world of shadows was an illusion. If anyone is “liberated and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck around and walk and look towards the light, he will suffer sharp pains: the glare will distress him, and he will be unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen only shadows; and then conceive someone saying to him, that what he saw before was only an illusion, but that, now, when he is approaching nearer to being and his eye is turned towards more real existence, he has a clear vision...Will he be perplexed? Will he not fancy that the shadows which he formally saw are truer than the objects which are shown to him?”

Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” goes: “Compare our nature in respect to education with our condition. Imagine men in an underground cave with an entrance open toward the light which extends through the whole cave. Within the cave are people who from childhood have had chains on their legs and their necks so they could only look forward but not turn their heads. There is burning a fire, above and behind them, and between the fire and the chains is a road above, along which one may see a little wall built along, just as the stages of conjurers are built before the people in whose presence they show their tricks. . . . Imagine then by the side of this little wall men carrying all sorts of machines rising above the wall, and statues of men and other animals wrought in stone, wood, and other materials, some of bearers probably speaking, others proceeding in silenced. . . . [Do you think] that such as these [chained men] would have seen anything alse of themselves or one another except the shadows that fall from the fire on the opposite side of the cave? How can they . . . if indeed they are forced to always keep their heads unmoved? . . . . [S]uch persons would believe that truth was nothing else but the shadows of the exhibitions. Let us inquire then, as to their liberation from captivity, and their cure for insanity. . . . [What if one of these chained persons was] let loose and obliged immediately to rise up, and turn round his neck and walk, and look upwards to the light, and doing all this still feel pained, and be disabled by the dazzling form seeing those things of which he formerly saw the shadows. What would he say if anyone were to tell him that he formerly saw mere empty visions, but now saw more correctly, as being nearer to the real thing, and turned toward what was more real. Then, what if you specially pointing out to him, and made him tell you the nature of what he saw. Do you think that he would be embarrassed? Do you think that he would think now that what he saw before was truer than what he sees now? [Source: Plato, The Republic, translated by George Burgess,(New York: Walter Dunne, 1901), Internet Archive, from CCNY]

“Even if a person could force him to look at the light itself, would he not have pain in his eyes and look away? And then, would not he turn to what he really could see [without pain] and think that these are really more clear than what had just been shown to him? But if a person was then to forcibly drag him out of the cave without stopping, until he was in the light of the sun, would he not be pained and indignant? Would not he, while in this light and having his eyes dazzled with the splendor, be able to see anything that he thought was true? No, he could not, at that moment. He would need to get some degree of practice if he would see things above him. First, he would most easily perceive the shadows, and then the images of men and other animals in the water, and after that the things themselves. And then he would more easily see the things in heaven, and heaven itself, by night, looking to the light of the stars and the moon, than after daylight to the sun and the light of the sun. How else? Finally, he might be able to perceive and contemplate the nature of the sun, not as respects its images in water or any other place, but itself by itself in its own proper place.

Plato and the Immortal Soul

Plato developed the concept of an immortal soul that would shape concepts of death and afterlife in Western philosophy. His concept of the soul was connected with his view of higher order of reality beyond that in the perceived world. His concept of death was similar to that of reincarnation. After death, a soul enriched by knowledge and notions of good, beauty and justice, Plato theorized, rose to higher planes in the universe. For most mortals though there was a judgment, some rewards and punishments, and then rebirth centuries later on earth.

In “ Phaedrus” , Plato wrote: for “the soul of a sincere lover of wisdom, or of one who has made philosophy his favorite...these, in the third period of a thousand years, if they have chosen this [philosopher’s] life thrice in succession, they thereupon depart, with their wings restored in the three thousandth year. Others are tried, some are sentenced to places of punishment beneath the Earth...others to some region in heaven...in the thousandth year they choose their next life.”

By the A.D. 3rd, century the neo-Platonist, like early Christians, believed the soul was a "fiery breath" that tended or rise towards heaven but became damp and heavy in the Earth’s atmosphere and was further weighted down by passions until it was brought down to earth. Many ordinary people believed in idea of the Islands of the Blest, a heaven with plentiful supplies of food and wine.

Plato on Transmigration of the Soul

On transmigration in the Myth of Er, Plato wrote in “Republic” X, 614: “Let me tell you,” said I, “the tale to Alcinous told that I shall unfold, but the tale of a warrior bold, Er, the son of Armenius, by race a Pamphylian. He once upon a time was slain in battle, and when the corpses were taken up on the tenth day already decayed, was found intact, and having been brought home, at the moment of his funeral, on the twelfth day as he lay upon the pyre, revived, and after coming to life related what, he said, he had seen in the world beyond.[Source: Plato. Republic, “Plato in Twelve Volumes,” Vols. 5 & 6 translated by Paul Shorey. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1969]

Plato

“He said that when his soul went forth from his body he journeyed with a great company and that they came to a mysterious region where there were two openings side by side in the earth, and above and over against them in the heaven two others, and that judges were sitting between these, and that after every judgement they bade the righteous journey to the right and upwards through the heaven with tokens attached to them in front of the judgement passed upon them, and the unjust to take the road to the left and downward, they too wearing behind signs of all that had befallen them, and that when he himself drew near they told him that he must be the messenger to mankind to tell them of that other world, and they charged him to give ear and to observe everything in the place.

On Judgement in the Underworld, Plato wrote in “Republic” X, 617-620: “Now when they arrived they were straight-way bidden to go before Lachesis, and then a certain prophet first marshalled them in orderly intervals, and thereupon took from the lap of Lachesis lots and patterns of lives and went up to a lofty platform and spoke, ‘This is the word of Lachesis, the maiden daughter of Necessity, “Souls that live for a day, now is the beginning of another cycle of mortal generation where birth is the beacon of death. No divinity shall cast lots for you, but you shall choose your own deity. Let him to whom falls the first lot first select a life to which he shall cleave of necessity. But virtue has no master over her, and each shall have more or less of her as he honors her or does her despite. The blame is his who chooses: God is blameless. “’ So saying, the prophet flung the lots out among them all, and each took up the lot that fell by his side, except himself; him they did not permit. [Source: Plato. Republic, “Plato in Twelve Volumes,” Vols. 5 & 6 translated by Paul Shorey. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1969]

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT GREEK IDEAS ABOUT DEATH AND THE SOUL europe.factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT GREEKS AND THE AFTERLIFE: HADES, ASPHODEL, JUDGEMENT AND TARTARUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Plato's Republic

In “The Republic” , Plato describes a utopia based on meritocracy, where the main virtue is wisdom and leaders, called guardians, are selected for their intellect and education. People live in communes and share everything. Luxuries are not permitted and people are not even allowed to go near gold or silver. Parents are not allowed to know who their children are and only the best and brightest offspring are allowed to have children themselves. Children judged inferior are killed at birth. Children allowed to survive are brought up in a state nursery and taken to wars as observers "to have their taste of blood like puppies." "Plato urged the banishment of the poet from the ideal republic because it provokes irrational thoughts and undisciplined emotions."

The 5,040 citizens of the Republic (the number of people that could be addressed by a single orator) selected 360 guardian that ruled on a rotating basis of 30 different guardians a month. Children went to school until they were 20 and were trained in gymnastics, music and intellectual activities. Those that did poorly on their exams became businessman, workers and farmers. The ones that did well received continued education in mathematics, science and rhetoric. The people who failed the tests became soldiers. The most able at the age of 35 were selected to command armies and the best officers was selected as ruler at the age of 50.◂

Plato's Republic and His Theory of the State

One of Plato’s earlier works is the Republic. In it he describes an ideal form of government, one that was better than the one that existed in Athens at the time. Plato thought that most people were ignorant and uneducated and thus felt they should not have the right to vote and decide what society should do. Instead, he argued that the best people should be chosen to be the Guardians of the rest. This view is not surprising when you consider that Plato came from a very rich family. [Source: Karen Carr, History for Kids]

In The Republic , Plato describes a utopia based on meritocracy, where the main virtue is wisdom and leaders, called guardians, are selected for their intellect and education. People live in communes and share everything. Luxuries are not permitted and people are not even allowed to go near gold or silver. Parents are not allowed to know who their children are and only the best and brightest offspring are allowed to have children themselves. Children judged inferior are killed at birth. Children allowed to survive are brought up in a state nursery and taken to wars as observers "to have their taste of blood like puppies." "Plato urged the banishment of the poet from the ideal republic because it provokes irrational thoughts and undisciplined emotions."

The 5,040 citizens of the Republic (the number of people that could be addressed by a single orator) selected 360 guardian that ruled on a rotating basis of 30 different guardians a month. Children went to school until they were 20 and were trained in gymnastics, music and intellectual activities. Those that did poorly on their exams became businessman, workers and farmers. The ones that did well received continued education in mathematics, science and rhetoric. The people who failed the tests became soldiers. The most able at the age of 35 were selected to command armies and the best officers was selected as ruler at the age of 50."

“In his "Republic" Plato sketches an ideal state, a polity which should exist if rulers and subjects would devote themselves, as they ought, to the cultivation of wisdom. The ideal state is modelled on the individual soul. It consists of three orders: rulers (corresponding to the reasonable soul), producers (corresponding to desire), and warriors (corresponding to courage). The characteristic virtue of the producers is thrift, that of the soldiers bravery, and that of the rulers wisdom. Since philosophy is the love of wisdom, it is to be the dominant power in the state: "Unless philosophers become rulers or rulers become true and thorough students of philosophy, there shall be no end to the troubles of states and of humanity" (Rep., V, 473), which is only another way of saying that those who govern should be distinguished by qualities which are distinctly intellectual. [Source: Catholic Encyclopedia Article, 1913 |=|]

” Plato is an advocate of State absolutism, such as existed in his time in Sparta. The State, he maintains, exercises unlimited power. Neither private property nor family institutions have any place in the Platonic state. The children belong to the state as soon as they are born, and should be taken in charge by the State from the beginning, for the purpose of education. They should be educated by officials appointed by the State, and, according to the measure of ability, which they exhibit, they are to be assigned by the State to the order of producers, to that of warriors, or to the governing class. These impractical schemes reflect at once Plato's discontent with the demagogy then prevalent in Athens and in his personal predilection for the aristocratic form of government. Indeed, his scheme is essentially aristocratic in the original meaning of the word; it advocates government by the (intellectually) best. The unreality of it all, and the remoteness of its chance to be tested by practice, must have been evident to Plato himself. For in his "Laws" he sketches a modified scheme which, though inferior, he thinks, to the plan outlined in the "Republic", is nearer to the level of what the average state can attain. |=|

The Republic on the Philosopher King

Plato and Aristotle in Rafael's "The School of Athens"

A discussion on “the philosopher king” in “The Republic” by Plato goes: “Inasmuch as philosophers only are able to grasp the eternal and unchangeable, and those who wander in the region of the many and variable are not philosophers, I must ask you which of the two classes should be the rulers of our State?

And how can we rightly answer that question?

Whichever of the two are best able to guard the laws and institutions of our State — let them be our guardians.

Very good.

Neither, I said, can there be any question that the guardian who is to keep anything should have eyes rather than no eyes?

There can be no question of that.

And are not those who are verily and indeed wanting in the knowledge of the true being of each thing,and who have in their souls no clear pattern, and are unable as with a painter's eye to look at the absolute truth and to that original to repair, and having perfect vision of the other world to order the laws about beauty, goodness, justice in this, if not already ordered, and to guard and preserve the order of them — are not such persons, I ask, simply blind?

Truly, he replied, they are much in that condition.[Source: Plato, “The Republic, 360 B.C., translated by Benjamin Jowett]

“And shall they be our guardians when there are others who, besides being their equals in experience and falling short of them in no particular of virtue, also know the very truth of each thing?

There can be no reason, he said, for rejecting those who have this greatest of all great qualities; they must always have the first place unless they fail in some other respect. Suppose, then, I said, that we determine how far they can unite this and the other excellences.

By all means.

In the first place, as we began by observing, the nature of the philosopher has to be ascertained. We must come to an understanding about him, and, when we have done so, then, if I am not mistaken, we shall also acknowledge that such a union of qualities is possible, and that those in whom they are united, and those only, should be rulers in the State.

What do you mean?

Let us suppose that philosophical minds always love knowledge of a sort which shows them the eternal nature not varying from generation and corruption.

Agreed.

“And further, I said, let us agree that they are lovers of all true being; there is no part whether greater or less, or more or less honorable, which they are willing to renounce; as we said before of the lover and the man of ambition.

True.

And if they are to be what we were describing, is there not another quality which they should also possess?

What quality?

Truthfulness: they will never intentionally receive into their minds falsehood, which is their detestation, and they will love the truth.

Yes, that may be safely affirmed of them.

"May be." my friend, I replied, is not the word; say rather, "must be affirmed:" for he whose nature is amorous of anything cannot help loving all that belongs or is akin to the object of his affections.

Right, he said.

And is there anything more akin to wisdom than truth?

How can there be?

Can the same nature be a lover of wisdom and a lover of falsehood?

Never.

Attributes of Plato’s Philosopher King

Plato wrote in “The Republic”: “The true lover of learning then must from his earliest youth, as far as in him lies, desire all truth?

Assuredly.

But then again, as we know by experience, he whose desires are strong in one direction will have them weaker in others; they will be like a stream which has been drawn off into another channel.

True.

He whose desires are drawn toward knowledge in every form will be absorbed in the pleasures of the soul, and will hardly feel bodily pleasure — I mean, if he be a true philosopher and not a sham one.

That is most certain.

Such a one is sure to be temperate and the reverse of covetous; for the motives which make another man desirous of having and spending, have no place in his character.

Very true.

Another criterion of the philosophical nature has also to be considered.

What is that?

There should be no secret corner of illiberality; nothing can be more antagonistic than meanness to a soul which is ever longing after the whole of things both divine and human.

Most true, he replied.

[Source: Plato, “The Republic, 360 B.C., translated by Benjamin Jowett]

“Then how can he who has magnificence of mind and is the spectator of all time and all existence, think much of human life?

He cannot.

Or can such a one account death fearful?

No, indeed.

Then the cowardly and mean nature has no part in true philosophy?

Certainly not.

Or again: can he who is harmoniously constituted, who is not covetous or mean, or a boaster, or a coward--can he, I say, ever be unjust or hard in his dealings?

Impossible.

Then you will soon observe whether a man is just and gentle, or rude and unsociable; these are the signs which distinguish even in youth the philosophical nature from the unphilosophical.

True.

There is another point which should be remarked.

What point?

Whether he has or has not a pleasure in learning; for no one will love that which gives him pain, and in which after much toil he makes little progress.

Certainly not.

And again, if he is forgetful and retains nothing of what he learns, will he not be an empty vessel?

That is certain.

Laboring in vain, he must end in hating himself and his fruitless occupation?

Yes.

“Then a soul which forgets cannot be ranked among genuine philosophic natures; we must insist that the philosopher should have a good memory?

Certainly.

And once more, the inharmonious and unseemly nature can only tend to disproportion?

Undoubtedly.

And do you consider truth to be akin to proportion or to disproportion?

To proportion.

Then, besides other qualities, we must try to find a naturally well-proportioned and gracious mind, which will move spontaneously toward the true being of everything.

Certainly.

Well, and do not all these qualities, which we have been enumerating, go together, and are they not, in a manner, necessary to a soul, which is to have a full and perfect participation of being?

They are absolutely necessary, he replied.

And must not that be a blameless study which he only can pursue who has the gift of a good memory, and is quick to learn--noble, gracious, the friend of truth, justice, courage, temperance, who are his kindred?

The god of jealousy himself, he said, could find no fault with such a study.

And to men like him, I said, when perfected by years and education, and to these only you will intrust the State.”

Platonic and Aristotlean View on Politics Versus Modern Realities

In a review of “On Politics”, by Oxford historian of Alan Ryan, Adam Kirsch wrote in The New Yorker: “By opening with historians such as Herodotus and Thucydides, rather than with Plato—the first political philosopher—Ryan makes clear his intention to place philosophy in its historical context, showing how given thinkers emerge from and react against the political worlds they inhabit. This is a difficult balancing act.... As Ryan shows, this historically grounded approach goes, to some extent, against the grain of Western political philosophy, which exhibits a recurring tendency to imagine that a life without politics is the best life. This explains the paradox that Plato’s “Republic,” the fountainhead of political philosophy, is not so much a treatise on politics as an attack on politics. Plato, living in an Athens whose democratic whims had resulted in the disaster of the Peloponnesian War and the execution of Socrates, had little faith in the power of the people to govern wisely or well. When he imagined the perfect city, he entrusted its government to a carefully bred and educated caste of guardians who would rule so intelligently and selflessly that political disagreement would simply never arise. [Source: Adam Kirsch, The New Yorker, October 29 & November 5, 2012 \~]

“Ryan observes, “The idea that ‘the many’ might have a legitimate interest in running their own lives just because they wish to is not one Plato entertains. This is an unpolitical politics, because the idea of legitimate but conflicting interests has no place.” The city is conceived not as a forum for competing individuals but as itself a macrocosmic individual, a human soul writ large; and, just as a soul in harmony with itself is happy, so a city in which everyone knows his own role will be happy. The assumptions behind this vision are, Ryan shows, as much metaphysical as they are political, which is one reason “On Politics” ends up being such a long book: in most cases, a thinker’s views of politics are indecipherable without his views of man, nature, and God. Only if we know what we are and why we are here can we decide how we should live together.

“Perhaps the key division between classical and modern political thought is the pre-modern assumption that we are here for a purpose and have a stable nature. Aristotle, whose teachings were at the heart of Western political thought for two millennia, was much more willing than Plato to acknowledge that politics is a dynamic and historical process. Yet he, too, based his vision of the good city on strong beliefs about what was natural and good for human beings. He had no hesitation about relegating women to the domestic sphere, since only men were naturally fit for politics. He endorsed slavery on the ground that some people are unfit for self-rule. For adult male citizens, on the other hand, politics was a necessary expression of their nature: “Man is by nature a political animal.” It followed that living in a polis was the best human life, enabling us to fulfill our true natures. The polis “grows for the sake of mere life,” he wrote, “but it exists for the sake of a good life.” This did not mean that democracy was the best form of government; on the contrary, Aristotle classified democracy as a corrupt version of politics, in which the resentful many claim power to expropriate the wealthy few. What he advocated was a balance between democracy and aristocracy, in which all the finest men had a chance to rule. Ryan reminds us that our concern for individual rights was alien to Aristotle: his question was not what rights every citizen has by virtue of being a citizen but, rather, what constitutional arrangements will produce a stable, successful government?” \~\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024