ANCIENT GREEK IDEAS ABOUT DEATH

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The ancient Greek conception of the afterlife and the ceremonies associated with burial were already well established by the sixth century B.C. In the Odyssey, Homer describes the Underworld, deep beneath the earth, where Hades, the brother of Zeus and Poseidon, and his wife, Persephone, reigned over countless drifting crowds of shadowy figures—the "shades" of all those who had died. It was not a happy place. Indeed, the ghost of the great hero Achilles told Odysseus that he would rather be a poor serf on earth than lord of all the dead in the Underworld (Odyssey, 11.489–91).” [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org]

The Greeks believed that at the moment of death the psyche, or spirit of the dead, left the body as a little breath or puff of wind. On the Greek notion of the psyche, or what survives after the death of the human body, John Adams of CSUN wrote: “ The Greeks do NOT agree as to its essence or its 'theology'. Some believe it is immortal, others not. All appear to believe that it is physical, not immaterial. Some believe it is a 'divine spark', others merely a constituent part of life ('breath of life'). Some believe in the transmigration of souls (metempsychosis), others that the psyche evaporates or dissipates shortly after death.” [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class ++]

Gods associated with death and afterlife include: 1) Hermes Psychopompos, a manifestation of Hermes, and his caduceus; and 2) Thanatos, offspring of Night (Nyx, Nox), brother of Hypnos (Sleep). But he is sometimes replaced by the Furies (Erinyes), who were produced from the blood of Ouranos falling upon Ge. The Furies specialize in pursuing murderers, especially patricides and matricides (see Aeschylus' play, The Eumenides). Thanatos is a character in Euripides' play Alcestis, where he wrestles with Heracles at the grave for the soul of Alcestis. ++

Around the six century B.C. the Orphic Greeks developed the mythology of the judgment which had been popular among the ancient Egyptians centuries before. Their Hades was governed by Pluto and Prosperpin and presided over by the judges Minos, Aeacus and Rhamadmanthis, the executioners and the Erineyes (See Below). Tartarus was a high-walled prison.

The early Jewish concept of Sheol and the later Christian concept of Heaven and Hell were partly based on the Greco-Roman belief of Hades. In the 4th century B.C., the Greeks thought the Blessed went to paradise-like Elysian Field. One of the first people to suggest the after death the soul was freed from the flesh and there was a judgement in which the Blessed were selected for the Elysian Fields was Plato.

The concept of Hades is closely associated with the myth of Orpheus. See Orpheus and Eurydice and Demeter and Persephone Under Myths.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEKS AND THE AFTERLIFE: HADES, ASPHODEL, JUDGEMENT AND TARTARUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Death in the Greek World: From Homer to the Classical Age” by Maria Serena Mirto and A.M. Osborne (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Early Greek Concept of the Soul” by Jan Bremmer (1983); Amazon.com;

“The Greek Way of Death” by Robert Garland (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Burial Customs of the Ancient Greeks” by Frank Pierrepont Graves (1869-1956) Amazon.com;

“Greek Burial Customs” by Donna Kurtz (1978); Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Necromancy” by Daniel Ogden (2004) Amazon.com;

“Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece” by Sarah Iles Johnston (1999) Amazon.com;

“Underworld Gods in Ancient Greek Religion” by Ellie Mackin Roberts (2022) Amazon.com;

“Persephone — Picture Book” for kids Amazon.com;

“Greek Heroes In and Out of Hades” by Stamatia Dova (2012) Amazon.com;

“The House of Hades: Studies in Ancient Greek Eschatology” by Lars Albinus (2000) Amazon.com;

“Greek & Roman Hell: Visions, Tours and Descriptions of the Infernal Otherworld” by Eileen Gardiner, Homer, Hesiod, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife” by Bart D. Ehrman Amazon.com ;

“Heaven: A History” by Colleen McDaniel and Bernard Lang Amazon.com ;

“Penguin Book of Hell” (illustrated) and edited by Scott Bruce (2018) Amazon.com ;

“The History of Hell” by Alice Turner(1993) Amazon.com ;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek Ideas About the Soul

The Greek concept of the soul changed over time. In the early days there were several souls, each with a different name and function, often residing in a particular part of the body. Thymos, for example resided in the chest and encompassed emotions, courage, fear and grief. Noos was associated with the mind and intellectual activity. It too was located in the chest.

The most important soul was the psyche. It was a breathy nebulous, spiritual soul that left the body when a person died. The word “psyche” comes from the Greek word meaning “to breath.” The Greek believed that the psyche of everyone went to Hades after they died. In the early days the psyche was portrayed as a kind of weak, moribund ghost. Later on vases it was depicted as a small winged figure.

Some myths such as Persephone and Demeter describe a kind of reincarnation. Some of the philosophers, notably the Pythagoreans, talked about the transmigration of souls (See Pythagoreans Under Philosophy). Other philosophers saw the psyche as a kind of supreme force that was connected to forces that ruled the universe.

Plato developed the concept of an immortal soul that would shape concepts of death and afterlife in Western philosophy. His concept of the soul was connected with his view of higher order of reality beyond that in the perceived world. His concept of death was similar to that of reincarnation. After death, a soul enriched by knowledge and notions of good, beauty and justice, Plato theorized, rose to higher planes in the universe. For most mortals though there was a judgment, some rewards and punishments, and then rebirth centuries later on earth.

In “ Phaedrus” , Plato wrote: for “the soul of a sincere lover of wisdom, or of one who has made philosophy his favorite...these, in the third period of a thousand years, if they have chosen this [philosopher’s] life thrice in succession, they thereupon depart, with their wings restored in the three thousandth year. Others are tried, some are sentenced to places of punishment beneath the Earth...others to some region in heaven...in the thousandth year they choose their next life.”

By the A.D. 3rd, century the neo-Platonist, like early Christians, believed the soul was a "fiery breath" that tended or rise towards heaven but became damp and heavy in the Earth’s atmosphere and was further weighted down by passions until it was brought down to earth. Many ordinary people believed in idea of the Islands of the Blest, a heaven with plentiful supplies of food and wine.

Hades, the Ancient Greek Underworld

Perserpone with Hades Hades was both the name of the Greek Underworld and the god that presided over it. After usurping the throne Zeus repelled attacks by giants and conspiracies by other gods. After the dethronement of the Titans a lottery with himself and his brothers Poseidon and Hades was held to decided who would occupy the heavens, the sea and the Underworld . Zeus won. He chose the heavens while Poseidon and Hades were awarded the sea and the Underworld respectively. The word “Hades” came from the Greek “ term a des” , meaning “the unseen” or concealed. It inhabitants were known as ‘shades.”

As a place Hades was a depressing Underworld where people went after they died. It wasn’t hell. It wasn’t a place of punishment for the wicked. It was more like purgatory. It was a place everyone went. No one received extreme forms of punishments other than famous mythological figures like Tantalus, Ixion and Tityos. Tantalus was a friend of Zeus who betrayed him and was condemned to the Underworld, where he sat for eternity next to a pool of water and fruit trees but was unable to drink or eat.

House of Hades was the official name for the Ancient Greek underworld and for the Palace of Hades. The Palace of Hades is where Hades, Persephone, the Furies, and others live. It was visited by Heracles, Orpheus, Theseus and Perithoos while they were alive during their heroic adventures. It is the goal of the Orphic initiate. The entrances to the 'House of Hades' were: 1) Taenarum at the southern tip of the Peloponnesus, in Spartan territory, used by Hercules and Orpheus; 2) Alcyonian Lake, near Lerna in Argos; cf the Hydra of Lerna; and 3) Lake Avernus, in Italy, near Pozzuoli on the north shore of the Bay of Naples, [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class ++]

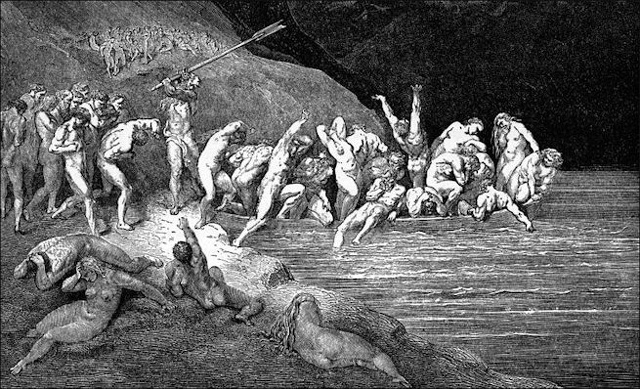

Rivers of the Underworld: 1) Styx: daughter of Oceanus and Tethys; married to Titan Pallas; children: Zelus (‘Zeal'), Nike (‘Victory'), Kratos (‘Strength'), Bia (‘Force') The inviolable oaths which the gods take are sworn by the River Styx (punishment for violation: one year in a coma, nine years in exile) 2) Lethe: (‘Forgetfulness') is very important in Pythagorean doctrines, which believes in the transmigration of souls; drinking the water must be avoided by Orphics, lest they forget their real divine nature and the secret words by which they can reach Persephone. 3) Phlegethon: (‘River of Flames'). 4) Cocytus (‘Wailing'). Charon, the Ferryman, was stationed at the River Styx. Each spirit had to pay him a coin for transportation across the river to the shores of the Fields of Asphodel. The unburied were not allowed to cross.++

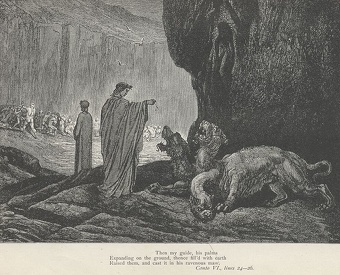

Gates of Hades: 1) Entry gates: open to all, but guarded by a descendant of Poseidon, three-headed dog Cerberus, who keeps souls from trying to leave. (b) Exit gates; only believed in by some (Homer and Vergil) The Gates of Ivory and Horn, through which false (but pretty) dreams and true dreams can ascend to the land of the living.

Plato and Empedocles On the Transmigration of the Soul

On transmigration in the Myth of Er, Plato wrote in “Republic” X, 614: “Let me tell you,” said I, “the tale to Alcinous told that I shall unfold, but the tale of a warrior bold, Er, the son of Armenius, by race a Pamphylian. He once upon a time was slain in battle, and when the corpses were taken up on the tenth day already decayed, was found intact, and having been brought home, at the moment of his funeral, on the twelfth day as he lay upon the pyre, revived, and after coming to life related what, he said, he had seen in the world beyond.[Source: Plato. Republic, “Plato in Twelve Volumes,” Vols. 5 & 6 translated by Paul Shorey. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1969]

“He said that when his soul went forth from his body he journeyed with a great company and that they came to a mysterious region where there were two openings side by side in the earth, and above and over against them in the heaven two others, and that judges were sitting between these, and that after every judgement they bade the righteous journey to the right and upwards through the heaven with tokens attached to them in front of the judgement passed upon them, and the unjust to take the road to the left and downward, they too wearing behind signs of all that had befallen them, and that when he himself drew near they told him that he must be the messenger to mankind to tell them of that other world, and they charged him to give ear and to observe everything in the place.

“And so he said that here he saw, by each opening of heaven and earth, the souls departing after judgement had been passed upon them, while, by the other pair of openings, there came up from the one in the earth souls full of squalor and dust, and from the second there came down from heaven a second procession of souls clean and pure and that those which arrived from time to time appeared to have come as it were from a long journey and gladly departed to the meadow and encamped there as at a festival, and acquaintances greeted one another, and those which came from the earth questioned the others about conditions up yonder, and those from heaven asked how it fared with those others.

“And they told their stories to one another, the one lamenting and wailing as they recalled how many and how dreadful things they had suffered and seen in their journey beneath the earth1—it lasted a thousand years—while those from heaven related their delights and visions of a beauty beyond words. To tell it all, Glaucon, would take all our time, but the sum, he said, was this. For all the wrongs they had ever done to anyone and all whom they had severally wronged they had paid the penalty in turn tenfold for each, and the measure of this was by periods of a hundred years each, so that on the assumption that this was the length of human life the punishment might be ten times the crime; as for example that if anyone had been the cause of many deaths or had betrayed cities and armies and reduced them to slavery, or had been participant in any other iniquity, they might receive in requital pains tenfold for each of these wrongs, and again if any had done deeds of kindness and been just and holy men they might receive their due reward in the same measure; and other things not worthy of record he said of those who had just been born and lived but a short time; and he had still greater requitals to tell of piety and impiety towards the gods and parents and of self-slaughter. For he said that he stood by when one was questioned by another ‘Where is Ardiaeus the Great?’ Now this Ardiaeos had been tyrant in a certain city of Pamphylia just a thousand years before that time and had put to death his old father and his elder brother, and had done many other unholy deeds, as was the report. So he said that the one questioned replied, ‘He has not come,’ said he, ‘nor will he be likely to come here.

On the transmigration of the soul, Empedocles (c. 490- 430 B.C.) wrote: “I wept and wailed when I saw the unfamiliar place. (Fragment 118)...For already have I once been a boy and a girl, a fish and a bird and a dumb sea fish. (Fragment 117)....There is an oracle of Necessity, ancient decree of the gods, eternal and sealed with broad oaths: whenever one of those demi-gods, whose lot is long-lasting life, has sinfully defiled his dear limbs ' with bloodshed, or following strife has sworn a false oath, thrice ten thousand seasons does he wander far from the blessed, being born throughout that time in the forms of all manner of mortal things and changing one baleful path of life for another. The might of the air pursues him into the sea, the sea spews him forth on to the dry land, the earth casts him into the rays of the burning sun, and the sun into the eddies of air. one takes him from the other, but all alike abhor him. Of these I too am now one, a fugitive from the gods and a wanderer, who put my trust in raving strife. (Fragment 115). [Source: Empedodes texts in “The Presocratic Philosophers”, translated by G. S. Kirk and J. E. Raven, Cambridge, Eng., 1957]

Plato On the Immortality of the Soul

Plato wrote in “Meno” 81: Socrates: ...I have heard from wise men and women who told of things divine...They were certain priests and priestesses who have studied so as to be able to give a reasoned account of their ministry; and Pindar also and many another poet of heavenly gifts. As to their words, they are these: mark now, if you judge them to be true. They say that the soul of man is immortal, and at one time comes to an end, which is called dying, and at another is born again, but never perishes. [Source: Plato, “Meno,” “Plato in Twelve Volumes,” Vol. 3 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1967]

“Consequently one ought to live all one's life in the utmost holiness.“For from whomsoever Persephone shall accept requital for ancient wrong,1 the souls of these she restores in the ninth year to the upper sun again; from them arise” “glorious kings and men of splendid might and surpassing wisdom, and for all remaining time are they called holy heroes amongst mankind.” Seeing then that the soul is immortal and has been born many times, and has beheld all things both in this world and in the nether realms, she has acquired knowledge of all and everything; so that it is no wonder that she should be able to recollect all that she knew before about virtue and other things.

“For as all nature is akin, and the soul has learned all things, there is no reason why we should not, by remembering but one single thing—an act which men call learning—discover everything else, if we have courage and faint not in the search; since, it would seem, research and learning are wholly recollection. So we must not hearken to that captious argument: it would make us idle, and is pleasing only to the indolent ear, whereas the other makes us energetic [81e] and inquiring. Putting my trust in its truth, I am ready to inquire with you into the nature of virtue.

Styx

Ancient Greek Burials Reveal Fear of Zombies

The ancient Greeks sometimes placed heavy objects, such as rocks and weighty ceramic vessels, on the bodies of people they feared might be revenants, or the living dead, better known as zombies. Researchers found two examples of revenant graves in the Greek city-state of Kamarina on southeastern Sicily. The skeletons in the graves were pinned down with heavy objects and rocks, as though people didn’t want the bodies to escape from their underground resting place. The researchers also found evidence of katadesmoi, also known as curse tablets, addressed to underworld deities. [Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, June 25, 2015]

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: Archaeologists have known about these two peculiar burials since the 1980s, when they uncovered the graves along with nearly 3,000 others at an ancient Greek necropolis in Sicily. But a new analysis suggests the two graves contained so-called "revenants," dead bodies thought to have the ability to reanimate, leave their graves and harm the living — essentially an ancient version of zombies.

The ancient Greeks believed that, "to prevent them from departing their graves, revenants must be sufficiently 'killed,' which [was] usually achieved by incineration or dismemberment," Carrie Sulosky Weaver wrote in the article, published June 11 in the online magazine Popular Archaeology. "Alternatively, revenants could be trapped in their graves by being tied, staked, flipped onto their stomachs, buried exceptionally deep or pinned with rocks or other heavy objects." [See Photos of the Ancient Greek 'Revenant' Burials]

One grave held the skeletal remains of an adult of unknown sex whose teeth had lines of arrested growth — a sign of serious malnutrition or illness, Sulosky Weaver said. The head and feet of the person were covered with "large amphora fragments… a large, two-handled ceramic vessel that was typically used for storing liquids," she wrote in the article. The heavy amphora fragments "were presumably intended to pin the individual to the grave and prevent it from seeing or rising," she added. Another grave contains the skeleton of a child, likely age 8 to 13. The skeleton didn't have any signs of disease, but five large stones were placed on top of it, possibly to stop a revenant from leaving the grave, Sulosky Weaver said.

To learn more, Sulosky Weaver surrounded herself with research on supernatural practices among the ancient Greeks. But the Greeks were not alone in their superstitions; other preindustrial societies had similar ways of viewing corpses of certain people, according to the research of folklore historian Paul Barber, she said. For example, outsiders, illegitimate children, or babies born with abnormalities or on an inauspicious day could be revenants, Sulosky Weaver said. Other candidates included suicides; victims of murder, drowning, plague and curses; and people who were not properly buried, she said.

The earliest example of revenant burials date to between 4500 and 3800 B.C. in Cyprus, where archaeologists found bodies in graves with millstones pinning down their heads and chests, according to the article. Another burial uncovered on the Peloponnese Peninsula dating to between 1900 and 1600 B.C. had a large rock over an individual in a stone-built tomb, Sulosky Weaver wrote. The work of other scholars shows that Greeks living in Kamarina also practiced with "magical" or "curse" tablets called katadesmoi, "so a supernatural explanation for the burials was possible," Sulosky Weaver said.

Evidence of these superstitions suggests the ancient Greeks didn't live in fear of the dead, but thought that some dead people could be dangerous or useful to the living, she said. "Some chose to recruit the dead to achieve specific goals, while others chose to trap potentially dangerous bodies in their graves to keep the living members of the community safe," Sulosky Weaver said. "These activities shed light on some of the lesser-known facets of Greek funerary practice."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024